Prenatal cannabis use is rising,1,2 and several qualitative studies indicate that pregnant women self-report using cannabis to manage stress and mood.3,4 However, few epidemiologic studies have examined whether pregnant women who suffer from mental health disorders and trauma are at elevated risk of using cannabis during pregnancy. Data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s (KPNC) large integrated healthcare system with universal screening for prenatal cannabis use by self-report and urine toxicology testing were used to examine the relation between depression, anxiety, and trauma diagnoses and symptoms and prenatal cannabis use.

METHODS

KPNC pregnant women with live births who completed a self-reported questionnaire on prenatal substance use and a urine toxicology test at their first prenatal visit (at ~8 weeks gestation) during standard prenatal care from 2012–2017 were included. Confirmatory tests were performed for positive toxicology tests. Of 219,071 pregnancies, 1,042 (0.5%) without date of last menstrual period, 21,115 (9.6%) without a toxicology test, and 892 (0.4%) who did not answer the question about self-reported cannabis use were excluded. The KPNC IRB approved this study and waived consent. This study followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Depressive and anxiety disorders and trauma diagnoses during pregnancy were ascertained from the electronic health record; self-reported depression symptoms (based on PHQ-95) and intimate partner violence (IPV) were assessed via universal screening at the first prenatal visit (eMethods).

The adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of any prenatal cannabis use (by self-report and/or a positive toxicology test) by mental health diagnoses/symptoms were estimated using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models in SAS 9.4 to account for women with multiple pregnancies during the study, adjusting for year, median neighborhood household income, age, and self-reported race/ethnicity.

RESULTS

The sample (N=196,022) was 35.7% White, 15.0% were aged <25, and the median neighborhood household income was $70,859 (IQR:$51,893-$93,036); 6.0% screened positive for prenatal cannabis (Table 1). The prevalence of mental health conditions ranged from 1.9% (IPV) to 11.0% (depression symptoms of at least moderate severity). Compared to women who did not use cannabis, those who used were younger, with lower incomes, were more likely to be African American or Hispanic and less likely to be Asian, and were more likely to have depression, anxiety and trauma diagnoses and symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 196,022 Pregnancies in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), 2012–2017, Overall and by Prenatal Cannabis Use

| Prenatal Cannabis Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N = 196,022 |

Yesa N = 11,681 (6.0%) |

No N = 184,341 (94.0%) |

P-valueb | |

| Characteristics | N (column %) | N (column %) | N (column %) | |

| Age (years) | <.001 | |||

| 13–17 | 1,628 (0.8) | 321 (2.8) | 1,307 (0.7) | |

| 18–24 | 27,858 (14.2) | 4,583 (39.2) | 23,275 (12.6) | |

| 25–34 | 124,176 (63.4) | 5,491 (47.0) | 118,685 (64.4) | |

| >34 | 42,360 (21.6) | 1,286 (11.0) | 41,074 (22.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| White | 69,925 (35.7) | 4,047 (34.7) | 65,878 (35.7) | |

| African-American | 10,481 (5.4) | 2,296 (19.7) | 8,185 (4.4) | |

| Hispanic | 54,704 (27.9) | 3,652 (31.3) | 51,052 (27.7) | |

| Asian | 34,334 (17.5) | 333 (2.9) | 34,001 (18.4) | |

| Other | 26,578 (13.6) | 1,353 (11.6) | 25,225 (13.7) | |

| Median household incomec | <.001 | |||

| < $51,893 | 48,948 (25.0) | 4,697 (40.3) | 44,251 (24.0) | |

| ≥ $51,893 - < $70,859 | 48,915 (25.0) | 3,020 (25.9) | 45,895 (24.9) | |

| ≥ $70,859 - < $93,036 | 48,938 (25.0) | 2,325 (19.9) | 46,613 (25.3) | |

| ≥ $93,036 | 48,947 (25.0) | 1,619 (13.9) | 47,328 (25.7) | |

| Mental Health Characteristics | ||||

| Depressive/Anxiety Disordersd | <.001 | |||

| No anxiety or depressive disorder | 170,541 (87.0) | 8,502 (72.8) | 162,039 (87.9) | |

| Anxiety disorder only | 9,697 (5.0) | 969 (8.3) | 8,728 (4.7) | |

| Depressive disorder only | 9,127 (4.7) | 1,235 (10.6) | 7,892 (4.3) | |

| Anxiety and depressive disorder | 6,657 (3.4) | 975 (8.4) | 5,682 (3.1) | |

| Self-Reported Depression Symptomse | <.001 | |||

| None | 114,537 (64.0) | 4,902 (46.2) | 109,635 (65.2) | |

| Mild | 44,698 (25.0) | 3,419 (32.2) | 41,279 (24.5) | |

| Moderate | 13,159 (7.4) | 1,415 (13.3) | 11,744 (7.0) | |

| Moderately severe/severe | 6,483 (3.6) | 875 (8.3) | 5,608 (3.3) | |

| Trauma Diagnosisd | <.001 | |||

| No | 191,337 (97.6) | 10,715 (91.7) | 180,622 (98.0) | |

| Yes | 4,685 (2.4) | 966 (8.3) | 3,719 (2.0) | |

| Self-Reported Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)f | <.001 | |||

| No | 176,503 (98.1) | 10,266 (95.6) | 166,237 (98.2) | |

| Yes | 3,489 (1.9) | 473 (4.4) | 3,016 (1.8) | |

Notes.

Six percent of pregnancies screened positive for prenatal cannabis use; 0.9% by self-report only, 3.4% by toxicology testing only, and 1.7% by both methods.

P-values were calculated using separate generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to account for some women having more than one pregnancy during the study period.

Median neighborhood household income was missing for 274 pregnancies (0.1%).

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes used to identify depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and trauma diagnoses during pregnancy (i.e., from last menstrual period through date of live birth) are provided in the eMethods.

Self-reported depression symptom categories are based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is given during standard prenatal care starting in 2012 (<5 none, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15+ moderately severe to severe depression); 17,145 pregnancies (8.8%) did not have data on PHQ-9 depression symptoms.

The three self-reported questions used to identify IPV at the first prenatal visit are also provided in the eMethods; 16,030 pregnancies (8.2%) did not have data on self-reported IPV.

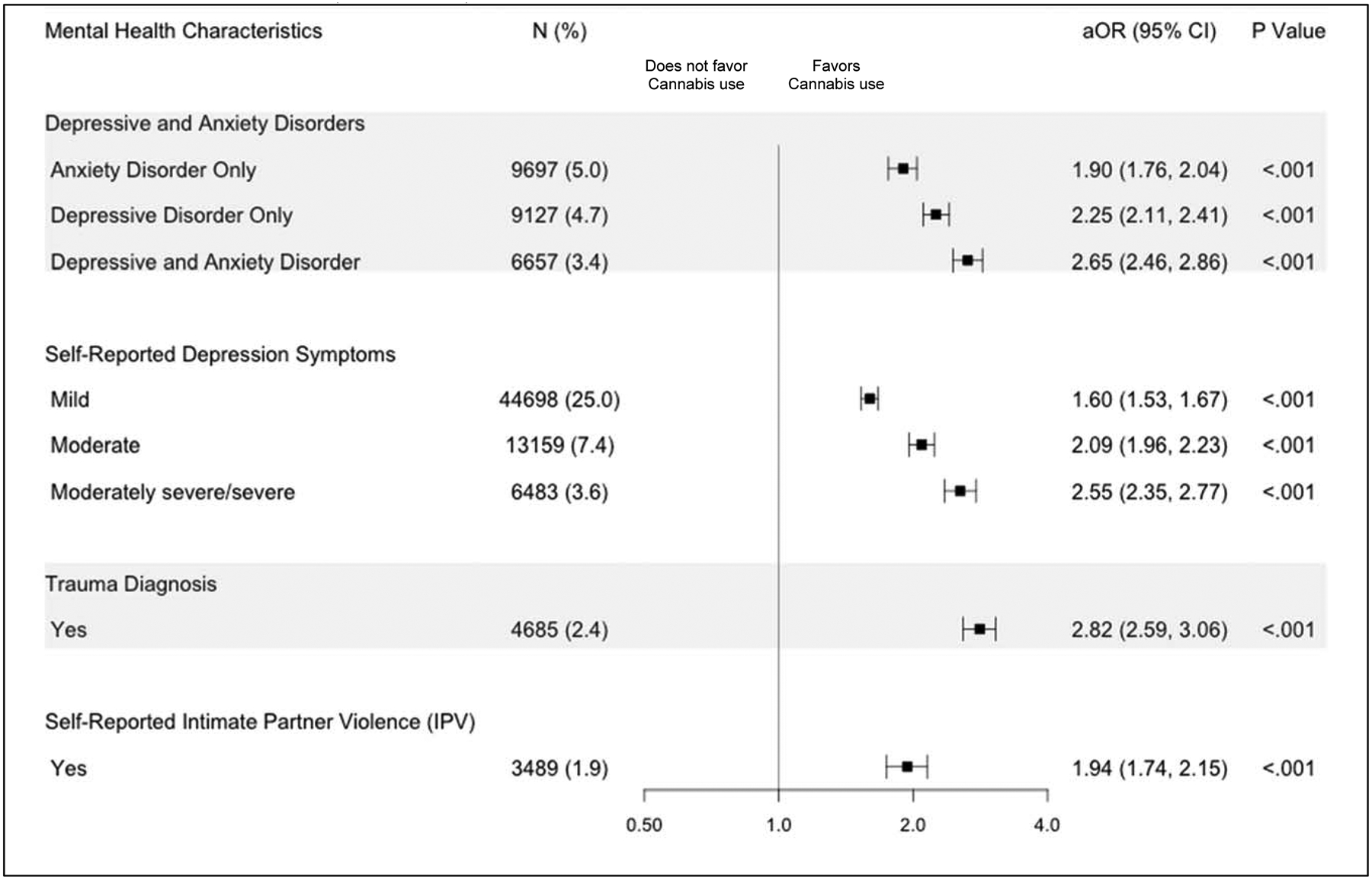

Compared to women without depressive or anxiety disorders, those with anxiety disorders (aOR=1.90, 95%CI:1.76–2.04), depressive disorders (aOR=2.25, 95%CI:2.11–2.41), or both (aOR=2.65, 95%CI:2.46–2.86) had greater odds of cannabis use (Figure 1). Similarly, relative to women without depression symptoms, those with mild (aOR=1.60, 95%CI:1.53–1.67), moderate (aOR=2.09, 95%CI:1.96–2.23), and moderately-severe-to-severe symptoms (aOR=2.55, 95%CI:2.35–2.77) had increased odds of cannabis use. Women with (versus without) a trauma diagnosis (aOR=2.82, 95%CI:2.59–3.06) and with (versus without) self-reported IPV (aOR=1.94, 95%CI:1.74–2.15) also had greater odds of cannabis use.

Figure 1: Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Cannabis Use During Pregnancy by Mental Health Characteristics (N = 196,022).

Notes. ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes used to identify depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and trauma diagnoses during pregnancy (i.e., from last menstrual period through date of live birth) are provided in the eMethods. Self-reported depression symptom categories are based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is given during standard prenatal care starting in 2012 (<5 none, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15+ moderately severe to severe depression); 17,145 pregnancies (8.8%) did not have data on PHQ-9 depression symptoms and were not included in analyses where depression symptoms were the predictor. The self-reported questions used to identify IPV are also provided in the eMethods; 16,030 pregnancies (8.2%) did not have data on self-reported intimate partner violence (IPV) and were not included in analyses were IPV was the predictor.

DISCUSSION

Depression, anxiety and trauma diagnoses and symptoms were associated with higher odds of cannabis use among pregnant women in California. Results support qualitative findings that pregnant women self-report using cannabis to manage mood and stress3,4, and suggest a dose-response relationship with higher odds of cannabis use associated with co-occurring depressive and anxiety disorders and greater depression severity. However, research is needed to determine the direction of these associations, as cannabis use might also cause or worsen mental health problems during pregnancy.

This study has several limitations. It takes place in one large healthcare system in California and findings may not generalize to all pregnant women. Cannabis screening in KPNC is limited to pregnant women at ~8 weeks gestation. Cannabis use may have occurred before women realized they were pregnant, and results do not reflect continued use throughout pregnancy. Further, we are unable to determine whether findings differ among non-pregnant women in KPNC. Finally, urine toxicology tests may infrequently detect pre-pregnancy cannabis use.

The health risks of prenatal cannabis use to the fetus are complex and may vary with administration mode and frequency of use, however, no amount of cannabis use during pregnancy has been shown to be safe.6 Pregnant women should be screened for cannabis use, asked about reasons for use, educated about potential risks, and advised to quit. Further, early screening for prenatal depression, anxiety, and trauma, and linkage to appropriate interventions might mitigate risk for prenatal cannabis use.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEGMENTS:

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by a NIH NIDA K01 Award (DA043604) and a NIH NIMH K01 Award (MH103444). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Lue-Yen Tucker and Varada Sarovar conducted the data analysis for this study. Dr. Young-Wolff had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal A, Rogers CE, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Carter EB, Lenze SN, Grucza RA. Alcohol, cigarette, and cannabis use between 2002 and 2016 in pregnant women from a nationally representative sample. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(1):95–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young-Wolff KC, Tucker LY, Alexeeff S, et al. Trends in self-reported and biochemically tested marijuana use among pregnant females in California from 2009–2016. JAMA. 2017;318(24):2490–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latuskie KA, Andrews NCZ, Motz M, et al. Reasons for substance use continuation and discontinuation during pregnancy: A qualitative study. Women Birth. 2019;32(1):e57–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang JC, Tarr JA, Holland CL, et al. Beliefs and attitudes regarding prenatal marijuana use: Perspectives of pregnant women who report use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;196:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e205–e209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.