Abstract

Therapies to lower gene expression in brain disease currently require chronic administration into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by intrathecal infusions or direct intracerebral injections. Though well-tolerated in the short-term, this approach is not tenable for a life-time of administration. Nose-to-brain delivery of enriched chitosan-based nanoparticles loaded with anti-HTT siRNA was studied in a transgenic YAC128 mouse model of Huntington’s Disease (HD). A series of chitosan-based nanoparticle (NP) formulations encapsulating anti-HTT small interfering RNA (siRNA) were designed to protect the payload from degradation “en route” to the target. Factors to improve production of effective nanocarriers of anti-HTT siRNA were identified and tested in a YAC128 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Four formulations of nanocarriers were identified to be effective in lowering HTT mRNA expression by at least 50%. Intranasal administration of nanoparticles carrying siRNA is a promising therapeutic alternative for safe and effective lowering of mutant HTT expression.

Keywords: gene-therapy, nanocarriers, intranasal administration, YAC128 mouse model, Huntington’s disease

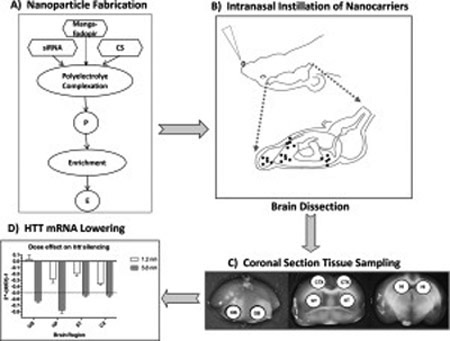

Graphical Abstract

A) Nanoparticles (NP) were synthesized by polyelectrolyte complexation of chitosan (CS) with anti-HTT siRNA and matrices were cross-linked with Mangafodipir. Flow chart of NP fabrication. P = provisional preparation; E = enriched preparation. Enrichment factor (EF) was calculated by formula: EF = Vp/Ve, where Vp volume of provisional preparation and Ve = volume of enriched preparation.

B) A series of NP formulations loaded with anti-HTT siRNA were tested in a Tg mouse model of Huntington’s Disease (Tg YAC128). Intranasal administration of NPs was followed by euthanasia and brain dissection at 48 and 120 hrs.

C) Sampling by micro-punch of olfactory bulb (OB), cerebral cortex (CTX), corpus striatum (ST) and hippocampus (HI)

D) Assays of HTT mRNA and protein in brain tissue samples revealed significant lowering of HTT expression in all four regions of brain.

Background

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is an inherited autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive deterioration in cognition, mood and motor control(1). The genetic mutation responsible for HD was localized to chromosome 4 and identified in 1992 as an expansion of a normal sequence of trinucleotide repeats (CAG) in Exon 1 of the HD gene (HTT) (2). The mutated HTT gene (mHTT) produces a misfolded protein (huntingtin, htt) that accumulates in neural cells causing gradual neuronal dysfunction and degeneration accounting for the gradual progression of clinical symptoms(2). Discovery of the genetic mutation led to development of animal models of HD for testing gene and drug therapies to mitigate or prevent disease progression (3). The administration of anti-HTT small interfering RNA (siRNA) or antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) in mouse and infrahuman models of HD was successful in decreasing expression of the gene and slowing or halting progression of disease. These pre-clinical results set the stage for clinical trials in patients with HD.

A clinical trial involving adults with early Huntington's disease was recently completed(4). This study was designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and properties of the anti-HTT ASO (Ionis-HTTRx) in patients with early-stage HD. Despite the capacity of ASO to significantly lower expression of the mutant gene for up to two months following a single injection(4), an obstacle to wide-spread application of this treatment relates to the invasive mode of delivery and the fact that it will require administration at least 6 times per year for the life-time of the patient. Lumbar puncture is relatively benign when used as a diagnostic procedure, but as a chronic portal into brain, there may be many adverse effects ranging from post-LP headaches, local infection, hemorrhage, arachnoiditis and radiculopathy. Considering this obstacle to chronic gene therapy, our laboratory is developing a series of nanoparticles (nanocarriers) designed to transport and distribute the siRNA or ASO from nose-to-brain, targeting in particular the cerebral cortex and striatum.

In present study we have developed a series of nanocarriers loaded with siRNA against human HTT, and evaluated the effects of each formulation in the YAC128 transgenic mouse model of HD that expresses the full-length human HD gene in addition to the murine HD gene (5). Final analysis of results identified key factors in formulation and fabrication of the NPs that optimized HTT-lowering efficacy in brain following intranasal administration.

Methods

Materials

Low molecular weight chitosan (mol. wt. 60,000-120,000 Da with 85% deacetylation) and chitosan lactate (mol. Wt. 4000-6000 Da) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, MO. Mangafodipir Trisodium was purchased from U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (Rockville, MD).

Five different siRNA compounds were packaged into nanoparticles (Table 1). Four of them were synthesized at the University of Massachusetts (UMASS) RNA Institute. Three of UMASS siRNA contained the same oligonucleotides to target exon 67 of HTT but the antisense strain of siRNA was varied by modifying the 3’ end with cholesterol or Diol. Thus, RNAs (Cy3 HTT 10150 - P2 VP – Chol, Cy3 HTT 10150 - P2 VP – Diol, Cy3 HTT 10150 - P2 VP) contained the same asymmetric oligonucleotides fragment targeting exon 67 of both mouse and human HTT gene. All oligonucleotides were fully chemically modified for maximal stability and a passenger strand was labeled with Cy3 dye at 5’ end. Two of antisense strands were hydrophobically modified with cholesterol and diol (6) and the third had no modification (see Table 1). The Cy3 HTT 10150 - P2 VP – Chol (packaged in NP1 and NP4) was chosen as a starting point in creation of the NP series because it had been demonstrated to be effective in lowering HTT mRNA and htt protein after direct intrastriatal injection to mice (6).

Table 1.

Characteristics of siRNA tested

| Name of siRNA | Strand | Chemical structure | HTT Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol | Antisense Sense | VP–5′–U#U#A:A:U:C:U:C:U:U:U:A:C#U#G#A#U#A#U#A–3′ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ TegChol–3′–A#A#U:U:A:G:A:G:A:A:A:U:G#A#C–5′–Cy3 |

Exon 67 |

| cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP- No Chol | Antisense Sense | VP–5′–U#U#A:A:U:C:U:C:U:U:U:A:C#U#G#A#U#A#U#A–3′ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ 3′–A#A#U:U:A:G:A:G:A:A:A:U:G#A#C–5′–Cy3 |

Exon 67 |

| cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Diol | Antisense Sense | VP–5′–U#U#A:A:U:C:U:C:U:U:U:A:C#U#G#A#U#A#U#A–3′ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ Diol–3′ –A#A#U:U:A:G:A:G:A:A:A:U:G#A#C–5′–Cy3 |

Exon 67 |

| s6491 | Antisense Sense | 5′–G:A:A:U:C:G:A:G:A:U:C:G:G:A:U:G:U:C:A:t:t–3′ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ 3′–g:a:C:U:U:A:G:C:U:C:U:A:G:C:C:U:A:C:A:G:U–5′ |

Exon 11 |

| Cy3-NTC-P2V-Chol | Antisense Sense | VP–5′–U#A#A:U:C:G:U:A:U:U:U:G:U:C#A#A#U#C#A#U–3′ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ ∣ TegChol–3′–A#U#U:A:G:C:A:U:A:A:A:C:A#G#U–Cy3 |

NA |

Color coding of chemical modification: Red −2’-O-Methyl ribose modification; Green −2’-Fluoro ribose modification; Purple -Vinylphosphonate (VP); Blue “:” - Phosphodiester bond and “#”- Phosphorothionate bond; Black – unmodified nucleosides and add-ons: Cy3- Cyanine fluorophore; TegChol - Tetraethylene glycol-Cholesterol; Diol - Divalent sense strand

Silencer Select siRNA (s6491) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. A scrambled siRNA used as non-target control was provided by UMASS.

TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix and primers for qPCR were obtained from ThermoFisher, including HTT (assay ID: Hs00918174_m1) and PPIB as a reference gene (assay ID: Mm00478295_m1).

Primers for genotyping, Platinum™ II Hot-Start Green PCR Master Mix (2X) were from ThermoFisher; Clonesaver Cards and GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder, were from Fisher Scientific Inc (Waltham, MA)

All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade. Ultrapure distilled DNase/RNase-free water purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA) was used for all experiments.

Nanoparticle preparations

Fabrication of nanoparticles, enrichment and stability testing were as described previously9-11 with some details specific for this study presented in Supplementary Data

The following nanoparticle preparations used for in vivo silencing experiments are showed in Table 2. Preparations obtained were between 103.7 and 205 nm average hydrodynamic size and from 42.5 to 54.7 mV of Z-potential. The most significant differences in these preparations were caused by enrichment procedure. Changes in enrichment factor from 1 to 4.8 allowed delivery of two different doses of siRNA carried by nanoparticles, namely 1.2 and 5.8 nmol. *See Supplementary Data for details

Table 2.

Nanoparticle preparations used in vivo silencing experiments

| Name of NP preparation |

NP matrix |

siRNA | Size (nm) | Z-potential (mV) |

*Enrichment Factor (EF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Naked” siRNA | NA | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol | NA | NA | 1 |

| NP 1 | CS | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol | 173.4±8 | 51±2.6 | 1 |

| NP 2 | CS | S6491 | 205±12.1 | 50.2±2.3 | 1 |

| NP 3 | CS | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Diol | 131.6±10.25 | 46.4±3.05 | 4.8 |

| NP 4 | CS | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol | 143±3.23 | 48.7±3.41 | 4.8 |

| NP 5 | CS | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP | 123.6±2.13 | 47.5±2.68 | 4.8 |

| NP 6 | CSL | cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP | 156.3±0.97 | 54.7±0.62 | 4.8 |

| NP 7 | CS | S6491 | 103.7±1.09 | 43.7±1.4 | 4.8 |

| NP 8 | CS | Non-target control | 110.9±2.6 | 42.5±2.4 | 4.8 |

See Supplementary Data for details

Animals and treatment

All procedures with animals were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol.

YAC128 transgenic (also known as FVB-Tg YAC128/ 53Hay/J line) and YAC128 non-carrier mice (stock No. 004938) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and breeding colonies were established in USF Comparative Medicine animal facility. The mice were housed under standard conditions with free access to water and food. For gene silencing experiments, we used early symptomatic 4-month-old female YAC128 transgenic mice.

Gene silencing experiments

Mice were treated with normal saline or siRNA containing nanoparticles via intranasal instillation. We used 5 different siRNA and non-target control siRNA. Before performing intranasal administration, mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane. Each mouse was gently grasped by the back of the neck with abdomen facing upwards while the NP containing solution (volume of 6 μL) was instilled in each nostril dropwise over 30 sec. Each animal received two cycles of instillation (total of 24 μl) at a single session in the morning and repeated session in the afternoon. This procedure was repeated next days. For HTT mRNA expression mice were treated for 2 days and for HTT protein expression study animals were treated for 2 or 5 days. Animals were euthanatized 48 and 120 hr after administration of the initial dose by decapitating quickly under isoflurane anesthesia in isolation from other mice, brains were removed, placed in cold mouse-brain mold for coronal sectioning as described below.

Tissue collection

Tissue sampling from olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, corpus striatum and hippocampus was performed by micro-punching of coronal sections of brain pretreated with RNAlater Stabilization solution. (See Supplementary Data).

Methods for evaluation of HTT silencing

Total RNA was extracted with RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The RNA was reverse transcribed using Invitrogen™ Superscript™ III Reverse Transcriptase kit with Invitrogen™ Oligo(dT) 20 Primer (Fisher Scientific).

Levels of mRNA expression were measured with QuantStudio 3 (ThermoFisher). TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (ThermoFisher,. MA) was used for quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) carried out in accordance to manufacturer protocol. Expression levels for huntingtin mRNA were normalized to PPIB (peptidylprolyl isomerase B) mRNA levels. . Primers for qPCR were obtained from ThermoFisher, including HTT (assay ID: Hs00918174_m1) and PPIB (assay ID: Mm00478295_m1). Htt protein concentrations in brain tissue were measured using a commercially available HTT ELISA kit Mouse and HTT ELISA kit Human (Aviva Systems Biology, CA, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. Wavelength readings were performed using Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek Instruments, Vermont, USA) and corrected by subtracting the readings at 540 nm from reading at 450 nm. Htt was quantified using standard curve of purified full-length htt proteins. The ELISA tests were performed in tissue samples from 4 regions of dissected brain tissue.

Statistical analysis

Means, SD, SEM, and P values were calculated by using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com) or Excel (Microsoft). Results are expressed as mean ± SD or SEM. HTT mRNA expression in brain regions is expressed as mean RQ-1 +/− SD; n = 5-6. Htt protein is expressed as mean concentration (pg/mg tissue) +/− SEM; n = 5. Statistical analysis utilized Two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA with correction for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism v6).

Results

Intranasal instillation of a series of NP formulations resulted in transport of the packaged anti-HTT siRNA from nasal epithelium into multiple brain regions where expression of HTT mRNA was lowered to various degrees. The extent of gene-lowering across brain regions was dependent on the formulation and size of the NP as well as dose of siRNA (see Table 3 for Summary of Results). Specific results are presented below to demonstrate a) effect of encapsulation vs “naked” siRNA, b) effect of dose, c) effect of siRNA structure and lipophility and d) compostion of the matrix.

Table 3.

Silencing effect of different siRNA preparations administered itself (naked) or transported by NP depending on composition and dose

| Preparations | siRNA cumulative dose, nmol* |

**Average silencing effect by regions (mean ± SEM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB | HP | ST | CX | ||

| cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol (naked) | 1.2 | −0.048+/−0.018 | −0.077+/−0.068 | −0.228+/−0.027 | −0.270+/−0.098 |

| NP 1 | 1.2 | 0.026+/−0.074 | −0.282+/−0.059 | −0.196+/−0.040 | −0.355+/−0.025 |

| NP 2 | 1.2 | −0.053+/−0.065 | −0.369+/−0.028 | −0.397+/−0.028 | −0.494+/−0.071 |

| NP 3 | 5.8 | −0.467+/−0.057 | −0.485+/−0.052 | −0.361+/−0.094 | −0.483+/−0.070 |

| NP 4 | 5.8 | −0.636+/−0.026 | −0.777+/−0.052 | −0.537+/−0.023 | −0.536+/−0.032 |

| NP 5 | 5.8 | −0.580+/−0.074 | −0.796+/−0.027 | −0.617+/−0.051 | −0.679+/−0.046 |

| NP 6 | 5.8 | −0.672+/−0.068 | −0.694+/−0.036 | −0.721+/−0.070 | −0.729+/−0.039 |

| NP 7 | 5.8 | −0.607+/−0.040 | −0.763+/−0.014 | −0.819+/−0.061 | −0.671+/−0.040 |

| NP 8 (NTC) | 5.8 | −0.002+/−0.015 | +0.023+/−0.048 | +0.008+/−0.017 | +0.059+/−0.074 |

Cumulative doses represent 4 sessions of intranasal administration. Each siRNA dose in a single session of administration was 0.3 nmol and 1.45 nmol for the primary (EF=1) and enriched (EF=4.8) preparation, respectively. N= 4 to 6 mice per formulation.

Silencing effect (SE) was calculated from qPCR cycle threshold (Ct) data by formula: SE = 2−ddCt-1 Where ddCt = (Ct htt– Ct ppib)treatment – (Ct htt– Ct ppib) control

Effects of encapsulated siRNA compared to “naked” siRNA administered intranasally

A small degree of silencing of HTT was achieved with “naked” cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP-Chol siRNA (without NP encapsulation) instilled intranasally. It lowered HTT mRNA by only an average of 16%. By contrast, other investigators have reported direct microinjection into mouse striatum of the same naked siRNA resulted in robust dose-dependent lowering, with up to 77% reduction in HTT mRNA expression(6).

The very small effect observed following intranasal administration of “naked” siRNA was likely due to lack of protection against nucleases provided by the NP encapsulation and the inability to deliver a higher dose of naked siRNA to the brain. The enriched preparation of this siRNA could not be produced because of accelerated decomposition of siRNA during the critical process of vacuum centrifugation. Encapsulation of siRNA into chitosan NP allows enrichment to higher doses without damaging siRNA and results in significant lowering of HTT expression.

Effect of Dose

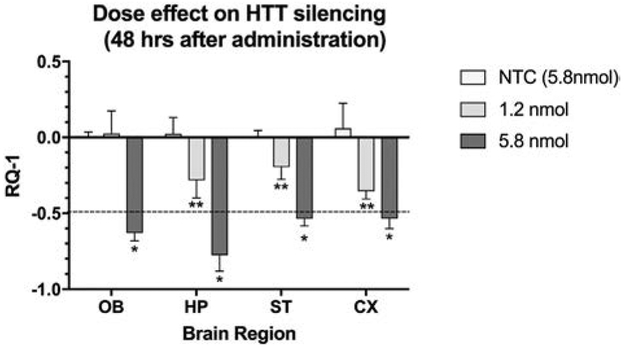

Implementation of our novel method of NP enrichment (see Supplementary Data) permitted production of various concentrations of siRNA packaged in the NPs. Two different siRNA doses (1.2 nmol and 5.8 nmol) and 5.8 nmol of scrambled non-target control (NTC) siRNA were administered in one set of experiments (see Fig. 1). The specific NP preparations utilized were NP1, for lower dose of siRNA, and NP4, for its higher dose. These specific formulations were packaged with hydrophobic siRNA and were chosen for study based on earlier work by researchers who demonstrated significant lowering of HTT mRNA and htt protein when microinjected into brain (6). Preparation NP8 was used as non-target control. The higher dose of siRNA delivered by NP4 was more effective than NP1 in lowering HTT mRNA expression and exceeded 50% reduction in all four regions of brain.

Figure 1.

Comparison of two doses of anti-HTT siRNA (1.2 and 5.8 nmol) and non-targeting control (NTC loaded with 5.8 nmol) in lowering HTT mRNA expression in four brain regions at 48h after administration. The NP4 preparation (see Table 2) was instilled twice per day for two days, followed by euthanasia. X-axis shows brain regions and Y-axis indicates the change in gene expression (RQ-1) at 48 hr. Each bar represents the mean ± SD with n = 5 mice per dose. Two-way ANOVA revealed that both dose and region contributed significantly to total variance (p < 0.001). With the higher dose (5.8 nmol), all brain regions showed a greater than 50% lowering of HTT mRNA at 48 hrs compared to NTC (* = p < 0.0001). At 1.2 nmol dose, all regions except olfactory bulb revealed lowering of HTT mRNA at 48 hr (** = p < 0.001). The dashed line indicates a 50% lowering from control, considered to a clinically relevant threshold for gene silencing.

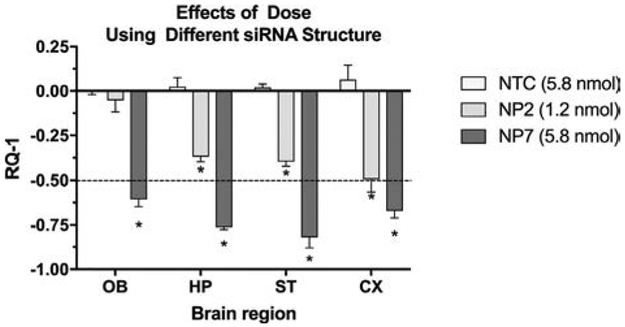

The dose-effect response was confirmed in a separate experiment using NP formulations (NP2 and NP7) carrying different siRNA payloads (s6491, see Table 1 for structure). NP7, which carried the higher concentration of siRNA, was more effective in gene silencing in all four brain regions than NP2 carrying the lower dose. (Fig.2)

Figure 2.

Comparison of two doses of anti-HTT siRNA (1.2 and 5.8 nmol) and NTC loaded with 5.8 nmol scrambled siRNA in lowering HTT mRNA expression in four brain regions at 48h after administration. The NP2, NP7 and NP8 preparations were instilled twice per day for two days, followed by euthanasia. NP2 and NP7 utilized commercially prepared siRNA of different structure than the other siRNA payloads. X-axis shows brain regions and Y-axis indicates the change in gene expression (RQ-1[VS1]). Each bar represents the mean ± SD with n = 5 mice per dose. With the higher dose (5.8 nmol) all brain regions showed a greater than 50% lowering of HTT mRNA at 48 hrs. 2-way ANOVA revealed that both brain region and dose contributed significantly to total variance (p < 0.0001). Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons of each brain region to NTC (NP8) reveals significant differences (* = p < 0.0001).

Effects of lipophlicity of the siRNA

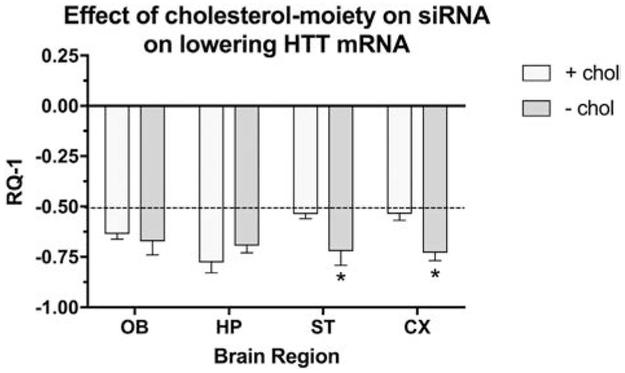

The effects of a hydrophobic siRNA was compared to non-hydrophobic siRNA (Fig. 3). Two formulations of siRNA were encapsulated into NP4 and NP5 and administered intranasally. YAC128 mice were euthanized 48 hrs after dosing. The presence or absence of a hydrophobic moiety on the siRNA had a significant in vivo effect on HTT lowering and appears to affect brain region specificity.

Figure 3.

Differences in HTT mRNA lowering depend on lipophilicity of the siRNA agent. X-axis = brain regions, Y-axis = RQ-1 (change in HTT mRNA expression expressed as mean SD). Both chol+(NP4) and chol- (NP5) siRNA were effective in lowering HTT expression by at least by 50% (dashed line). The siRNA without the cholesterol moiety (NP5) was more effective in lowering HTT in striatum and cerebral cortex as compared to the formulation with cholesterol (NP4). (n = 5 mice per group; * = p < 0.05 with Dunnett’s corrections for multiple comparisons).

The cholesterol moiety attached to siRNA made silencing of HTT less efficient in striatum and cortex, while there were no significant differences between formulations NP4 and NP5 in the olfactory bulb and hippocampus. Administration of siRNA with less hydrophobic properties appears to preferentially target HTT in striatum and cortex, at least after 48 hrs. How the duration of silencing in striatum and cortex changes over longer time frames will need to be studied going forward.

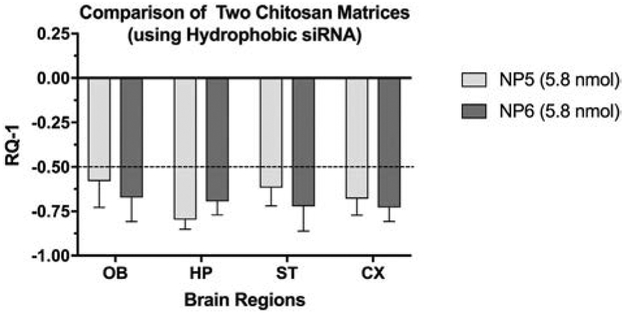

Exploring whether a variation in the chitosan (use of chitosan lactate) would further enhance efficacy of the less hydrophobic siRNA (i.e. no cholesterol attached), we packaged the siRNA in chitosan lactate as a matrix for polyelectrolyte complication. This preparation named as NP6 was compared to NP5 which contained the same siRNA but used the standard chitosan matrix. Both of these preparations were as effective if not more than the other preparations in silencing across all brain regions but the chitosan lactate matrix did not significantly change efficacy (Fig.4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of matrix variation on HTT mRNA lowering. Chitosan (NP5) was compared to chitosan lactate (NP6) as the matrix for complexation of cy3 HTT 10150-P2VP siRNA (no cholesterol). X-axis = brain regions, Y-axis = mean RQ-1 +/− SD (n = 5). Both preparations were highly effective in lowering mRNA expression compared to treatment with NCT (NP8).

Effect on lowering HTT protein expression

The primary endpoint in studying a series of NPs was reduction of HTT mRNA and not htt protein expression. Given that the siRNA packaged in NP4 was the starting point in generation of this series, we examined htt protein expression in brain tissues following administration of the NP4 formulation (the same formulation shown to lower HTT mRNA in Fig 1). Experimental YAC128 mice were treated with NP4 twice a day for 2 and 5 days; the overall dose administered was 5.8 and 14.5 nmol. Animals were euthanized at 48 and 120 h after the beginning of treatment. As expected intranasal instillation of the NP4 formulation was effective in lowering HTT protein expression (Fig.5), but the effect required more time to become evident, presumably due to the time required for cellular clearance of accumulated mutant HTT protein.

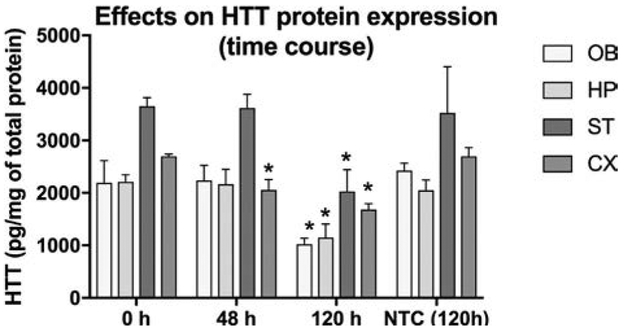

Figure 5.

Htt protein lowering at 48 and 120 hrs after intranasal instillation of NPs bearing anti-htt siRNA (NP4) or bearing non-targeting siRNA (NTC or NP8). Data are expressed as mean SD (n = 5 mice per time point). Y-axis indicates tissue concentrations of htt protein. X-axis indicates time in hours after NP administraton. The htt protein level is lowered significantly compared to control (Time = 0) or compared to NTC treatment, in all brain regions at 120 hrs following intranasal instillation. Htt protein is also reduced at 48 hr, compared to control (Time = 0) or NTC, but only in cerebral cortex. Two-way ANOVA showed that both brain and time contributed significantly to the total variance. Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests of differences from control (Time = 0) or from NTC at 120 hr in each brain region are statistically significant. (* = p < 0.05)

YAC128 mice treated with NP8 (NP carrying scrambled siRNA) expressed significantly higher levels of HTT protein than NP4 treated animals in all brain regions (Fig 5). Forty-eight hours after treatment with NP4 the protein levels were not lowered in OB, HP, and ST but there was slightly decreased in cortex. The levels of htt protein remained elevated despite significantly decreased mRNA expression (Fig.1). However, after five days, all regions of brain showed significantly decreased protein expression. These results indicate that lowering HTT protein levels from brain tissue is a slower process than lowering HTT mRNA transcripts following anti-HTT siRNA administration. The highest reduction of htt protein was observed in olfactory bulb (53%). In HP, ST and CX magnitude of reduction reached 48, 45 and 38%, respectively. Decreases of mutant htt protein of more than 50% are consistently associated with benefits in preclinical models, providing guidance for the degree of HTT lowering likely to be safe and effective in human trials of HTT lowering therapies (7).

Discussion

The findings reported here are consistent with earlier studies from our laboratory that demonstrated transport of manganese-containing NPs from nose to various regions of brain, evidenced by measurements in brain tissue of Cy3-labeled siRNA and by effective lowering of a target gene (8). In addition, the earlier studies tracked the time-dependent distribution across various brain regions of manganese-containing NPs by MRI (T1-weighted images). In the present report, the focus was on optimizing NP design to produce the most effective lowering of HTT mRNA expression.

Using a series of siRNA structures and NP formulations, we have identified key parameters that can be manipulated to optimize gene silencing when the siRNA is delivered by the intranasal route. The key factors include the concentration of siRNA achieved by enrichment, the structure and lipophilicity of siRNA as well as the use of a protective chitosan matrix. All but one of the siRNA structures packaged into NPs utilized a chitosan matrix. Simply administering “naked” siRNA intranasally did not significantly reduce brain HTT mRNA expression significantly, despite the fact that direct intracerebral injection of the same “naked” siRNA was highly effective in lowering HTT expression (6).

Chitosan is used as a NP matrix because it polymerizes to form compact nanoparticles due to electrostatic interactions between positive charged moieties of its amino groups and negative charged phosphate moieties of the siRNA structure (8). The NPs formulated for these experiments also incorporated Mangafodipir as a cross-linking agent to stabilize the globular structure of NP and protect siRNA from degradation (9). At same time the chitosan NP does not bind the siRNA too tightly, as we have recently reported, allowing release of siRNA to participate in gene silencing (10). Another advantage of the Mn-containing NPs is the capacity to track the transport and distribution to brain by MRI T1-weighted imaging as was reported in our earlier studies (8)

Other matrices in addition to chitosan have been studied in our laboratory but we have focused on chitosan for the following reasons (10). Chitosan is biodegradable (11) and can be digested by lysozymes produced by animals. Therefore, it is practically non-toxic (in mammals, with LD50 of 16 g/kg in rats) (12). Chitosan/siRNA complexes form nanoparticles (13) with a proper size around 200 nm adequate for in vivo delivery. Release of structurally intact siRNA from the nanoparticles, an essential prerequisite for nanocarrier-mediated RNA gene silencing was demonstrated previously (10).

Our earlier work demonstrated that physical and chemical stability of NP formulations were critical factors in determining NP dosage forms, delivery route and application (10). Common physical stability issues include sedimentation, agglomeration or crystal growth. A widely used strategy to alleviate sedimentation problems when developing self-stabilized nanoparticle suspensions, is to decrease particle size and increase medium viscosity(14).

For medical applications, stable NP will be needed to deliver therapeutic doses. Common approaches to enhance chemical stability are to transform the nanosuspensions into dry solid dosage form (15) or to increase the concentration of the nanosuspensions(16). Centrifugal evaporation was utilized to prepare NP formulations evaluated in this study (See Supplementary data). This procedure rapidly removed solvent while the samples themselves were not heated to damaging temperatures. With centrifugal evaporation, particles do not undergo physical stress and in the concentrated state, nanoparticles are kinetically frozen and there is no dynamic exchange of the individual polymer chains, as the movement of the active agents inside and outside of the polymer aggregate is restrained(17).

It is worth comparing reduction of mutant HTT reported here with results of a recent study in HD subjects (4). Administration of anti-HTT ASO directly into the intrathecal space (CSF) in early HD patients resulted in a dose-dependent reduction (up to 42% lowering) in concentration of CSF mutant htt, the protein that putatively causes Huntington’s disease (4, 7). It is too soon to know whether this reduction reflects a lowering of mutant htt in brain parenchyma, although preclinical studies support the hypothesis that concentrations of mutant htt protein in the CSF reflect the concentrations of mutant htt in central nervous system tissue(18). Before this approach to treat HD can be translated to human trials, we will need to move forward to chronic treatment in animals with larger brains (Tg sheep model of HD). We plan to study the effects of chronic intermittent administration of the most effective NPs bearing anti-HTT siRNA with a focus on the relationship between htt protein levels in brain and concentrations in CSF. With this approach, the impact of chronic, intermittent intranasal treatment on disease progression in a larger animal will benefit from having an in vivo biomarker (htt protein) of efficacy. Measurement of the same biomarker of disease progression used in the current clinical trials will reduce the need for frequent euthanasia of sheep for access to brain and will facilitate translation of intranasal administration of gene therapy to humans.

In summary, nose-to-brain delivery of chitosan-based nanoparticles loaded with anti-HTT siRNA is a promising therapeutic approach for safe and effective lowering of mutant HTT expression to mitigate the progression of Huntington’s disease. Encapsulation of siRNA in chitosan protected the payload from degradation “en route” to the target. In the fabrication of stable chitosan-based NP, the concentration limitations are a major obstacle to effective gene silencing when it is to be administered by the intranasal route. Fabrication of NP of relatively small size (100-160 nm) is also an important factor for successful intranasal delivery. The nature of interaction between siRNA and chitosan require that fabrication of NP occur in relatively diluted concentrations which hinder therapeutic potential. Therefore, the ability to fabricate concentrated NP preparations without damaging siRNA content is a critical factor for successful intranasal delivery of gene silencing agents. Delivery of gene therapy by intranasal delivery will have to be scaled up and tested in larger brains (e.g. sheep brain or infra-human primate) before translation to human clinical trials in subjects with neurodegenerative diseases such as HD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: R01 NS095563 (09/01/2015 to 08/31/2020) to JSR, University of South Florida and NIH instrumentation grant S10 OD020012 to AV, University of Massachusetts, Worcester

We thank Dr. Shijie Song, Dr. X. Kong, Dr. Subhra Mohapatra and Dr. Neil Aronin, for the help and advice in carrying out of this research. We also thank Kunyu Li for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ross CA, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington's disease: from molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Lancet neurology. 2011;10(1):83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell. 1993;72(6):971–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramaswamy S, McBride JL, Kordower JH. Animal Models of Huntington's Disease. ILAR Journal. 2007;48(4):356–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabrizi SJ, Leavitt BR, Landwehrmeyer GB, Wild EJ, Saft C, Barker RA, et al. Targeting Huntingtin Expression in Patients with Huntington's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrante RJ. Mouse models of Huntington's disease and methodological considerations for therapeutic trials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792(6):506–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alterman JF, Hall LM, Coles AH, Hassler MR, Didiot MC, Chase K, et al. Hydrophobically Modified siRNAs Silence Huntingtin mRNA in Primary Neurons and Mouse Brain. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids. 2015;4:e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabrizi SJ, Ghosh R, Leavitt BR. Huntingtin Lowering Strategies for Disease Modification in Huntington's Disease. Neuron. 2019;101(5):801–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez-Ramos J, Song S, Kong X, Foroutan P, Martinez G, Dominguez-Viqueria W, et al. Chitosan-Mangafodipir nanoparticles designed for intranasal delivery of siRNA and DNA to brain. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2018;43:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Ramos J, Sava V, Song S, Mohapatra S, Mohapatra S, inventors DIVALENT-METAL COATED NANOPARTICLES FOR DELIVERY OF COMPOSITIONS INTO THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM BY NASAL INSUFFLATION 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fihurka O, Sanchez-Ramos J, Sava V. Optimizing Nanoparticle Design for Gene Therapy: Protection of Oligonucleotides from Degradation Without Impeding Release of Cargo. Nanomed Nanosci Res. 2018;2(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escott GM, Adams DJ. Chitinase activity in human serum and leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1995;63(12):4770–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandy T, Sharma CP. Chitosan--as a biomaterial. Biomater Artif Cells Artif Organs. 1990;18(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard KA, Rahbek UL, Liu X, Damgaard CK, Glud SZ, Andersen MO, et al. RNA interference in vitro and in vivo using a novel chitosan/siRNA nanoparticle system. Mol Ther. 2006;14(4):476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Zhang J, Watanabe W. Physical and chemical stability of drug nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011. ;63(6):456–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Eerdenbrugh B, Van den Mooter G, Augustijns P. Top-down production of drug nanocrystals: nanosuspension stabilization, miniaturization and transformation into solid products. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2008;364(1):64–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vauthier C, Cabane B, Labarre D. How to concentrate nanoparticles and avoid aggregation? Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;69(2):466–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marques R, Helmy R, Waterhouse D. Enhancing radiolytic stability upon concentration of tritium-labeled pharmaceuticals utilizing centrifugal evaporation. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2015;58(6):261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southwell AL, Smith SE, Davis TR, Caron NS, Villanueva EB, Xie Y, et al. Ultrasensitive measurement of huntingtin protein in cerebrospinal fluid demonstrates increase with Huntington disease stage and decrease following brain huntingtin suppression. Scientific reports. 2015;5:12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.