Abstract

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a widely used analgesic drug, which can cause severe liver injury after an overdose. The intracellular signaling mechanisms of APAP-induced cell death such as reactive metabolite formation, mitochondrial dysfunction and nuclear DNA fragmentation have been extensively studied. Hepatocyte necrosis releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) which activate cytokine and chemokine formation in macrophages. These signals activate and recruit neutrophils, monocytes and other leukocytes into the liver. While this sterile inflammatory response removes necrotic cell debris and promotes tissue repair, the capability of leukocytes to also cause tissue injury makes this a controversial topic. This review summarizes the literature on the role of various DAMPs, cytokines and chemokines, and the pathophysiological function of Kupffer cells, neutrophils, monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages, and NK and NKT cells during APAP hepatotoxicity. Careful evaluation of results and experimental designs of studies dealing with the inflammatory response after APAP toxicity provide very limited evidence for aggravation of liver injury but support of the hypothesis that these leukocytes promote tissue repair. In addition, many cytokines and chemokines modulate tissue injury by affecting the intracellular signaling events of cell death rather than toxicity of leukocytes. Reasons for the controversial results in this area are also discussed.

Keywords: Acetaminophen-induced liver injury, innate immune response, inflammasome, neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages

1. Introduction

Acetaminophen (APAP, N-acetyl-p-aminophenol, paracetamol) is a widely studied drug due to its hepatotoxic potential after an overdose in both experimental animals and humans. The key intracellular signaling mechanisms of cell death in hepatocytes are known (Ramachandran and Jaeschke, 2019). It involves first the formation of a reactive metabolite NAPQI by the cytochrome P450 system, in particular Cyp2E1 (Zaher et al., 1998). NAPQI is detoxified by hepatic GSH and also binds to sulfhydryl groups of cellular proteins (McGill and Jaeschke, 2013). Protein adducts formation, especially on mitochondrial proteins, triggers an initial mitochondrial oxidant stress that is amplified by a mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade resulting in the ultimate activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Hanawa et al., 2008; Saito et al., 2010a). The amplified mitochondrial oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation is responsible for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening leading to the collapse of the membrane potential and matrix swelling (Kon et al., 2004). This results in the rupture of the outer membrane and release of intermembrane proteins such endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) into the cytosol and translocation to the nucleus where these endonucleases cause extensive DNA fragmentation (Cover et al., 2005; Bajt et al., 2006). Massive mitochondrial dysfunction and swelling together with DNA damage causes programmed cell necrosis (Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke et al., 2019).

The presence of neutrophils and monocytes during APAP-induced liver injury has been recognized for some time but the mechanisms of hepatic recruitment in the absence of an infection were only more recently described (Kubes and Mehal, 2012; Jaeschke et al., 2012). Although it is undisputed that these phagocytic cells are needed to remove cell debris and make room for new cells that are being regenerated, a substantial controversy ensued whether these inflammatory cells may also aggravate the initial injury. The current review describes some of the basis for a sterile inflammatory response and the evidence for and against the role of inflammation as a second hit of toxicity in APAP hepatotoxicity.

2. DAMPs and the Initiation of Sterile Inflammation

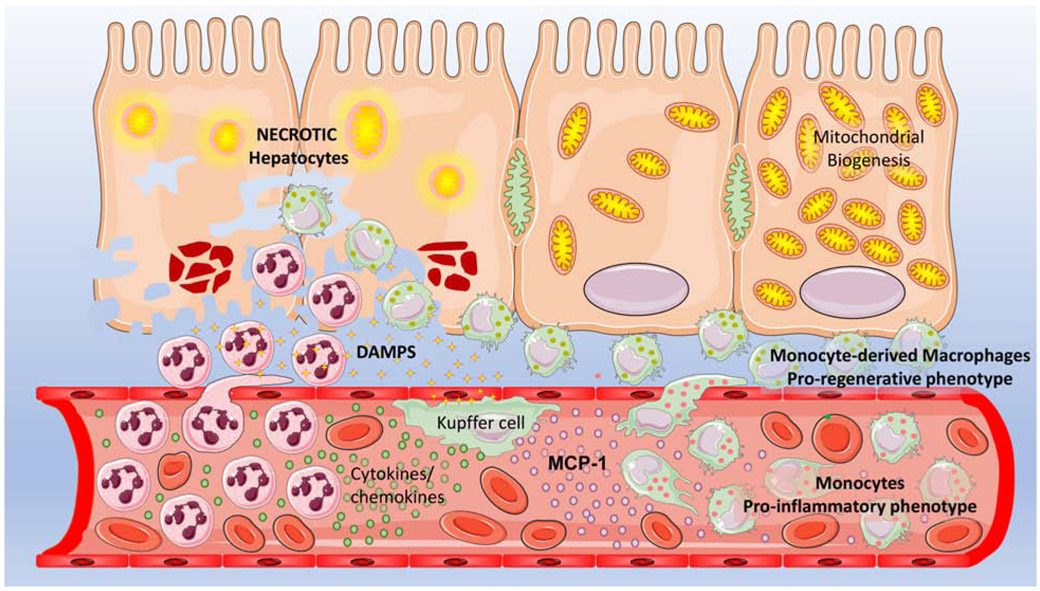

During necrotic cell death there is a passive release of intracellular molecules, which are termed damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (Bianchi, 2007) (Figure 1). These include high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein, mitochondrial DNA, nuclear DNA fragments and histones, ATP, uric acid and many others (Kubes and Mehal, 2012; Roh and Sohn, 2018). Importantly, many of these DAMPs bind to pattern recognition receptors such as toll like receptors (TLRs) mainly on macrophages where they can trigger transcriptional activation of cytokine and chemokine genes (Kubes and Mehal, 2012; Roh and Sohn, 2018). Thus, interventions targeting DAMPs have been considered as therapeutic approaches against APAP hepatotoxicity, though several caveats exist. For example, nuclear DNA fragments and mitochondrial DNA, which are released during APAP hepatotoxicity in mice and humans (McGill et al., 2012a), bind to TLR9 and induce pro-IL-1β (He et al., 2017; Imaeda et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2015) and IL-1α (Zhang et al., 2018) after APAP overdose. Pro-IL-1β requires the proteolytic cleavage by caspase-1 to generate the active cytokine (Van de Veerdonk et al., 2011). Caspase-1 is activated by the Nalp3 inflammasome (Sutterwala et al., 2006), which is assembled in response to binding of ATP to the purinergic receptor (P2X7) on macrophages (Di Virgilio et al., 2017). The P2X7 receptor has been implicated in APAP toxicity through both reduced inflammasome activation in gene KO mice and with a P2X7 receptor antagonist (Hoque et al., 2012). However, the P2X7 antagonist was shown to protect against APAP toxicity by inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes independent of inflammasome activation (Xie et al., 2013). In support of the inflammasome concept, IL-1β mRNA is attenuated in TLR9-deficient mice in response to APAP toxicity (Imaeda et al., 2009). IL-1β protein expression but not the mRNA can be reduced with a pancaspase inhibitor (Williams et al., 2010b) and in mice deficient of caspase-1, and the inflammasome components ASC and Nalp3 (Imaeda et al., 2009).

Figure 1: The sterile inflammatory response to APAP-induced hepatocyte necrosis.

Hepatocyte necrosis after an APAP overdose results in release of DAMPS such as HMGB1 as well as mitochondrial and nuclear DNA fragments. These activate toll like receptors on resident Kupffer cells, which release cytokines and chemokines which then results in transmigration and infiltration of non-primed neutrophils into the necrotic area which facilitates removal of cell debris. Release of cytokines like MCP-1 from Kupffer cells recruits bone marrow derived monocytes, which arrive with a pro-inflammatory phenotype, but mature into a pro-regenerative phenotype once they transmigrate into the milieu surrounding the necrotic cells. These macrophages then facilitate recovery and regeneration of surviving hepatocytes around the necrotic area by activating mitochondrial biogenesis and enhancing hepatocyte division to activate liver recovery after APAP-induced injury.

Another important DAMP is HMGB1 (Klune et al., 2008), which has been shown to be released during APAP toxicity in mice (Antoine et al., 2009; Martin-Murphy et al., 2010) and humans (Antoine et al., 2012). HMGB1 can bind to TLR4 on macrophages and trigger cytokine formation during APAP toxicity (Cai et al., 2014). In contrast, it has been suggested that HMGB1 binds directly to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) on neutrophils, which seems to be responsible for neutrophil recruitment and cytotoxicity after APAP overdose (Huebener et al., 2015). However, another study showed no protection with anti-HMGB1 antibodies or soluble RAGE (Kim et al., 2018) directly contradicting the previous report by Huebener et al., (2015). Antibodies against HMGB1 reduced complement activation and hepatic neutrophil recruitment but had no effect on APAP-induced injury (Kim et al., 2018; Scaffidi et al., 2002) suggesting that HMGB1 release by necrotic cells can either directly or indirectly trigger a neutrophilic inflammatory response through activation of complement. However, consistent with other direct interventions against neutrophils discussed later, this neutrophil activation does not enhance liver injury. This lack of protection against APAP toxicity by anti-HMGB1 antibodies was also confirmed by others (Yang et al., 2012) but contradicted by a study where glycyrrhizin-induced inhibition of HMGB1 attenuated the APAP-induced inflammatory response (Wang et al., 2013). The authors suggested that the released HMGB1 from necrotic hepatocytes after an APAP overdose binds to TLR4 on Kupffer cells, which then produce IL-23. The secreted IL-23 stimulates γδT cells to generate IL-17A, which recruits neutrophils and causes an assumed neutrophil-mediated injury (Wang et al., 2013). Although the presented data seem to support the conclusions, the results contradict a series of other investigations including those indicating that HMGB1 acts directly on neutrophils and not on macrophages (Huebener et al., 2015), that HMGB1 antibodies do not protect against APAP toxicity (Kim et al., 2018; Scaffidi et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2012), that elimination of Kupffer cells actually aggravates the liver injury (Ju et al., 2002) and neutrophil inhibition does not protect (Cover et al., 2006; Lawson et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2010a). Another concern is that blocking HMGB1 can delay regeneration without affecting the early injury (Yang et al., 2012). Together these studies with many different and contradicting effects of HMGB1 on APAP-induced liver injury suggest that HMGB1 may not be the best therapeutic target.

Heat shock proteins (HSPs), which are induced as acute phase proteins during stress, have been measured in plasma after APAP overdose in mice and were assumed to be a DAMP (Martin-Murphy et al., 2010). However, concerns were raised whether HSPs act as DAMPs during sterile inflammation (van Eden et al., 2012). The main arguments against HSPs being DAMPs are that the main receptors HSPs bind to, TLR2 and TLR4, are not always pro-inflammatory, that HSPs are present in circulation under physiological conditions and that immunization with HSPs is anti-inflammatory (van Eden et al., 2012). In addition, HSPs are induced during APAP toxicity (Salminen et al., 1997) and HSP70i-deficient mice showed an increased injury (Tolson et al., 2006). Furthermore, the protective effect of several natural products involves the induction of HSPs (Li et al., 2014; Nishida et al., 2006). The protective mechanism of HSP72 overexpression against APAP toxicity correlates with reduced oxidant stress and JNK activation (Levada et al., 2018). Thus, intracellular HSPs have a strong protective effect against APAP-induced liver injury and there is limited evidence that increased levels of HSPs in circulation may have a relevant pro-inflammatory effect.

Given the numerous DAMPs that are being released by necrotic cells (Roh and Son, 2018), it is unclear why eliminating a single DAMP may have a relevant effect on the initiation of the inflammatory response. Thus, targeting a single DAMP may seem a somewhat limited strategy to reduce a potentially detrimental inflammatory response. In addition, one should not ignore the fact that the main purpose of this inflammatory response is to remove cell debris and promote regeneration. Therefore, a too aggressive approach in limiting the sterile inflammation by eliminating circulating DAMPs may impair the recovery (Vénéreau et al., 2015).

3. Role of Inflammatory Cells in APAP Hepatotoxicity

3.1. Neutrophils

One of the most contentious topics in APAP toxicity is the role of neutrophils. These inflammatory cells are the first line of defense against bacterial infection due to their rapid recruitment to the site of inflammation and their effective killing mechanisms (Liew and Kubes, 2019). However, because of their potential cytotoxicity, neutrophils can also cause acute tissue damage (Liew and Kubes, 2019) including liver injury under various pathophysiological conditions (Jaeschke, 2006, 2011). An increasing number of neutrophils can be found in the liver as early as 6 h after an overdose, i.e. in the middle of the intracellular injury phase, and consistent with a sterile inflammatory response (Lawson et al., 2000; Cover et al., 2006) (Figure 1). Importantly, in contrast to observations in experimental models such bile duct ligation or hepatic ischemia-reperfusion where neutrophils cause the injury (Jaeschke et al., 1993; Gujral et al., 2003), these early neutrophils do not seem to be activated or primed (Lawson et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2010a, 2014). Furthermore, using blocking antibodies against β2 integrins (CD18) did not attenuate APAP-induced injury (Lawson et al., 2000) but they effectively protected against ischemia-reperfusion injury (Jaeschke, et al., 1993, Liu et al., 1995). Similarly, animals who had a genetic deficiency of CD18 were not protected against APAP toxicity (Williams et al., 2010a) but were completely protected against BDL-induced liver injury (Gujral et al., 2003). The confusing finding that these interventions did not reduce the overall number of neutrophils in the liver is easily explained by the fact that these adhesion molecules are not necessary for neutrophils to accumulate in the sinusoids (Jaeschke et al., 1996) but are critical for neutrophil transmigration and attack on hepatocytes (Jaeschke and Smith, 1997). This has been clearly demonstrated with an anti-ICAM-1 antibody, the counterreceptor for CD18, which did not prevent neutrophil recruitment after galactosamine-endotoxin but prevented transmigration of neutrophils and the neutrophil-mediated injury (Essani et al., 1995). Again, ICAM-1-deficient mice were not protected against APAP-induced liver injury (Cover et al., 2006).

In addition to the neutrophil recruitment, it is also established that neutrophils typically cause tissue damage by reactive oxygen, i.e. hypochlorous acid (Prokopowicz et al., 2012; Weiss, 1989). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) have not been observed and no pathophysiological role of NETs has been found in APAP toxicity (He et al., 2017). The neutrophil-specific, highly reactive oxygen species is generated by myeloperoxidase from chloride and hydrogen peroxide, which is derived from superoxide generated by NAPDH oxidase (NOX2) (Prokopowicz et al., 2012; Weiss, 1989). Thus, inhibitors of NADPH oxidase eliminated the neutrophil-mediated oxidant stress and liver injury during endotoxemia or hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury without affecting neutrophil recruitment (Hasegawa et al., 2005; Gujral et al., 2004). On the other hand, neither deficiency of NADPH oxidase nor inhibition of the enzyme protected against the APAP-induced oxidant stress and liver injury (Cover et al., 2006; James et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2019). Overall, among these direct intervention strategies against neutrophils, which are all consistently effective in models of neutrophil-mediated liver injury, none of them did affect APAP hepatotoxicity in mice. A more recent study suggested that mtDNA/TLR9-mediated induction of miR-223 in neutrophils may down-regulate the activation of these inflammatory cells (He et al., 2017). This may be an explanation for the overwhelming evidence against a direct neutrophil toxicity during APAP-induced liver injury (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evidence for Involvement of Neutrophils in the Pathophysiology of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity and Repair

| Neutrophils promote injury | Neutrophils do not affect injury but promote repair |

|---|---|

| Pretreatment with neutropenia antibody protects (Liu et al, 2006; Marques et al., 2012) - this approach is questioned due to off-target effects (Jaeschke and Liu, 2007) | Treatment with CD18-blocking antibodies does not protect (Lawson et al., 2000) |

| Partial protection with elastase-deficient mice (Huebener et al., 2015) | CD18-deficient mice are not protected (Williams et al., 2010a) |

| ICAM-1-deficient mice are not protected (Cover et al., 2006) | |

| Post-treatment with neutropenia antibodies (Gr-1, Ly6G) does not protect (Cover et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2019) | |

| NADPH oxidase inhibitors do not protect (Cover et al., 2006) | |

| gp91phox-deficient mice (no functional NADPH oxidase) are not protected (James et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2014) | |

| Enhanced neutrophil recruitment into liver with endotoxin or IL-1β does not enhance APAP-induced liver injury (Williams et al., 2010a,b) | |

| Reduced hepatic neutrophils recruitment by interfering with DAMPs such as uric acid does not protect (Kono et al., 2010) | |

| Reduced circulating neutrophils in GcsF-deficient mice does not protect (Yang et al., 2019) | |

| No activation of circulating and liver neutrophils during the early injury phase (Lawson et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2010a, 2014) | |

| No activation of circulating neutrophils during the progression of APAP-induced liver injury in humans; activation occurs only during the recovery phase (Williams et al., 2014) | |

| Genetic neutropenia or neutropenia induced by Ly6G prevents the resolution of the injury indicating that neutrophils are involved in tissue repair (Yang et al., 2019) | |

| Neutrophils promote the conversion of pro-inflammatory monocytes/macrophages to the reparative phenotype and thus promote tissue repair (Yang et al., 2019) |

Publications on APAP-induced liver injury and recovery with interventions directed at modulating neutrophil activities and/or recruitment. APAP, acetaminophen; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; GcsF, Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL-1β, interleukin-1β.

The findings in the mouse model also applies to the human pathophysiology as neutrophil activation is not observed during the peak of injury but occurs only during the recovery phase (Williams et al., 2014). Consistent with these human data, a recent experimental study provided evidence that neutrophils promote the conversion of the infiltrating monocytes from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-reparative phenotype indicating that neutrophils are indirectly promoting tissue repair after APAP-induced liver injury (Yang et al., 2019).

The only evidence in support of a neutrophil-induced injury after APAP overdose came from studies that depleted neutrophils 24 h ahead of APAP administration (Liu et al., 2006; Ishida et al., 2004; Marques et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). However, the fundamental concern with this approach is that the selective depletion of blood neutrophils using antibodies administered i.v., results in most of them ending up stuck in capillary beds like sinusoids, where they are being recognized by Kupffer cells and removed. The extensive phagocytosis of the inactivated neutrophils leads to activation of Kupffer cells (Bautista et al., 1994) resulting in acute phase gene activation in surrounding hepatocytes (Jaeschke and Liu, 2017). These genes include inflammatory genes and heat shock proteins, heme oxygenase 1 and metallothionein 1 and 2 (Jaeschke and Liu, 2017). When carried out 24h prior to APAP administration, the induction of genes like metallothionein before APAP administration comes down to a preconditioning effect, which increases the resistance to APAP toxicity (Saito et al., 2010b). Thus, this protective effect of neutropenia initiated 24 h before APAP is caused by acute phase gene induction rather than the absence of neutrophils. The fact that the same neutropenia-inducing antibody does not protect when it is administered shortly after APAP further confirms that it is not the lack of neutrophils in circulation, but rather, the absence of the preconditioning effect which is responsible for the beneficial effect of the antibody (Cover et al., 2006). Consistent with these findings, neutropenia induced by delayed treatment with the neutrophil-specific antibody Ly6G or genetic neutropenia had no effect on the APAP-induced injury phase (Yang et al., 2019). Again, similar acute neutropenia induction effectively protects against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (Jaeschke et al., 1990). Thus, despite these very real off-target effects of prolonged neutropenia before APAP treatment, which were discussed in several reviews (Jaeschke, et al., 2012; Woolbright and Jaeschke, 2017a,b), this questionable intervention strategy continues to be used as evidence for neutrophil involvement in the injury phase (Marques et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018).

3.2. Kupffer cells

Kupffer cells, the liver-resident macrophage population, are critical for host defense but can be activated by many different stresses and cause potential tissue damage (Bilzer et al., 2006). In fact, Kupffer cells were one of the first cell types to be implicated in APAP hepatotoxicity. Morphological evidence for Kupffer cell activation was initially reported (Laskin and Pilaro, 1986). In addition, in the same rat model, Kupffer cell inactivation with gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) was shown to be partially protective against APAP-induced liver injury (Laskin et al., 1995). However, these data have never been reproduced; in addition, the rat is a very poor model for APAP hepatotoxicity (McGill et al., 2012b).

A study from Michael and colleagues used GdCl3 to eliminate the oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation and APAP-induced liver injury in a mouse model (Michael et al., 1999) suggesting that Kupffer cells are the main source of peroxynitrite and the dominant cause of APAP-induced liver injury. However, there are some serious concerns with these results and conclusions. First, the profound protection reported here was never reproduced with GdCl3 (Ito et al., 2003; Ju et al., 2002; Knight and Jaeschke, 2004). Second, it makes little sense that the most active Kupffer cells located in the periportal area cause a selective centrilobular injury. Third, actual elimination of Kupffer cells by clodronate liposomes aggravated the injury rather than protected (Ju et al., 2002). Fourth, deficiency of NADPH oxidase activity, the critical source of superoxide for all phagocytes including Kupffer cells, did not affect the oxidant stress or peroxynitrite formation and the liver injury after APAP (James et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2014). Thus, definitive experiments (clodronate liposomes, NADPH oxidase deficiency) virtually eliminate Kupffer cells as a relevant source of oxidant stress and as a cytotoxic inflammatory cell type directly involved in APAP-induced liver injury (Table 2). Any involvement of Kupffer cells in the inflammatory response is likely caused by cytokine formation. In contrast, the enhanced liver injury in the absence of Kupffer cells points towards a beneficial effect. It has been suggested that Kupffer cell-derived IL-10 may be responsible for limiting inducible nitric oxidase synthase (iNOS) induction, which attenuates peroxynitrite formation and liver injury (Bourdi et al., 2002). Recent data also indicates that hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2α reprograms Kupffer cells through interleukin 6 (IL-6) production to protect against APAP-induced liver injury (Gao et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Evidence for Involvement of Macrophages in the Pathophysiology of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity and Repair

| Macrophages promote injury | Macrophages do not affect injury but promote repair |

|---|---|

| Inactivation of Kupffer cells with GdCl3 is protective in rats (Laskin et al., 1995) and mice (Michael et al., 1999) | Inactivation of Kupffer cells with GdCl3 does not protect (Ju et al., 2002; Knight and Jaeschke, 2004) |

| Reducing recruitment of bone marrow-derived monocytes in CCR2-deficient mice are partially protected against the early but not the late injury phase (Mossanen et al., 2016) | Elimination of Kupffer cells with clodronate liposomes enhances liver injury (Ju et al., 2002; Campion et al., 2008). |

| gp91phox-deficient mice (no functional NADPH oxidase) are not protected (James et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2014) | |

| Reducing hepatic infiltration of monocytes by CCR2- or MCP-1 gene deficiency or use of an anti-CCR2 antibody does not affect the injury but delays repair (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008; You et al., 2013; Graubardt et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019) |

Publications on APAP-induced liver injury and recovery with interventions directed at modulating Kupffer cell activities or recruitment of monocytes. APAP, acetaminophen; GdCl3, gadolinium chloride; MCP-1 monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2).

Another unresolved issue is the claim that Kupffer cells are depleted during APAP toxicity (Dambach et al., 2002; Zigmond et al., 2014). The partial disappearance of Kupffer cells could be caused by a direct toxic mechanism of APAP as was shown in mouse macrophage J774.2 cells leading to apoptotic cell death (Al-Belooshi et al., 2010). However, as has been repeatedly shown, pan-caspase inhibitors do not protect or in any way affect APAP hepatotoxicity in vivo (Lawson et al., 1999; Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2010b). In addition, it remains unclear if these Kupffer cells die or if it is just a loss of the F4/80 antigen. A “loss” of Kupffer cells has been suggested after treatment with GdCl3 (Edwards et al., 1993) but isolation of Kupffer cells from animals after GdCl3 treatment did not show a reduced cell number but functional inactivation (Liu et al., 1995).

3.3. Bone Marrow-derived Monocytes

Monocytes are cells of the innate immune system with a critical host defense function but can also contribute to tissue injury and progression of disease (Karlmark et al., 2012). After an APAP overdose in mice, bone marrow-derived monocytes are recruited into the area of necrosis within 12-24 h (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008). The main chemokine responsible for the recruitment is CCL2 (MCP-1) (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008) (Figure 1). These monocytes are characterized by high expression of Ly6C, pro-inflammatory genes such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 and angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (You et al., 2013; Zigmond et al., 2014). The high levels of CCL2 observed after APAP (Antoniades et al., 2012) can mature the pro-inflammatory monocytes to a pro-regenerative phenotype, which is characterized by high expression of IL-10 and increased phagocytosis capacity (Sierra-Filardi et al., 2014). The Ly6Chigh monocytes dominate during the first 24 h after APAP but almost disappear during the regeneration phase (Zigmond et al., 2014). However, the pro-regenerative Ly6Clow monocytes, which are present in limited quantity at 24 h, are the dominant phenotype during regeneration (48-72 h), which suggests the maturation of the newly infiltrated monocytes (Zigmond et al., 2014). Recent evidence suggest that neutrophils may promote this phenotypic change (Yang et al., 2019). However, despite this pro-inflammatory phenotype of the newly recruited monocytes, reducing the recruitment of these cells in mice deficient in the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) (Dambach et al., 2002) or its receptor CCR2 (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008, You et al., 2013) or the ablation of monocyte recruitment with an anti-CCR2 antibody (Graubardt et al., 2017) did not affect APAP-induced liver injury during the first 24 h but delayed hepatocellular regeneration and angiogenesis between 24 and 96 h. These data strongly suggest that the main purpose of these bone marrow-derived monocytes, which are present predominantly in the necrotic area, is to remove necrotic cell debris and promote repair. The regeneration phase in the mouse model lasts between 24-96 h depending on the dose of APAP (Bhushan et al., 2014). High levels of CCL2 in circulation and the presence of pro-regenerative macrophages and to a lesser degree neutrophils in areas of necrosis are observed during APAP-induced acute liver failure in humans (Antoniades et al., 2012) suggesting that similar mechanisms of monocyte recruitment and maturation to the pro-regenerative phenotype also occur in patients. Other mediators that reprogram monocytes towards a pro-regenerative phenotype during APAP-induced acute liver failure is secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (Antoniades et al., 2014) and in an experimental model neutrophil-derived miR-223 (Calvente et al., 2019) and neutrophil-induced reactive oxygen formation (Yang et al., 2019). On the other hand, Ly6Chi monocytes promote neutrophil activation and survival and the Ly6Clow monocyte-derived macrophages promote apoptosis and removal of neutrophils, which is critical for the resolution of inflammation (Graubardt et al., 2017). Together, these findings suggest an important crosstalk between these inflammatory cells with the goal of tissue repair and resolution of the inflammatory response (Table 2).

Another more recent publication assessed the recruitment of various leukocytes into the liver during the first 24 h after APAP (Mossanen et al., 2016). The authors confirmed previous results including the early recruitment of neutrophils (≥ 6 h), the lack of or limited infiltration of NK and NKT cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the gradual depletion of Kupffer cells, and the significant recruitment of Ly6Chigh monocytes. In addition, the pro-inflammatory gene expression profile of the Ly6Chigh monocytes was also confirmed (Mossanen et al., 2016). However, the new aspect of the study was that the authors found a difference in injury between CCR2-deficient mice and wild type animals at 12 h after APAP due to the reduced monocyte infiltration, which were 60% Ly6Chigh monocytes (Mossanen et al., 2016). These findings were confirmed with the use of a CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor, which also reduced monocyte infiltration and injury at 12 h. However, the inhibitor did not reduce liver injury at 24 h despite a lower number of monocytes (Mossanen et al., 2016). Furthermore, the authors still observed an 80% reduction of monocytes in CCR2 KO mice at 24 h but did not report any injury data (Mossanen et al., 2016). If one assumes that they observed no difference in injury at 24 h as previously reported (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008; You et al., 2013; Graubardt et al., 2017), the question remains about the relevance of the transient delay in the early injury by blocking monocyte infiltration. Mossanen et al. (2016) also observed no effect on regeneration with the CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor after 48 h, which contrasts with previous reports where the CCR2 KO mice showed a substantial delay in recovery (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008). It is unclear if this is caused by the limited efficacy of the CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor or if this is a pharmacokinetic problem. In either case, the data do not provide convincing evidence that targeting infiltrating monocytes is a promising therapeutic approach for early presenting patients. Importantly, N-acetylcysteine and other emerging drugs are likely much more effective in preventing APAP-induced acute liver failure in these patients (Jaeschke et al., 2020).

3.4. Natural Killer Cells and Natural Killer T Cells

Besides the resident macrophages, the liver contains a large number of additional immune cells including natural killer (NK) and NK T cells (Tian et al., 2013). Depletion of both NK and NKT cells with an antibody seemed to attenuate APAP-induced liver injury (Liu et al., 2004). However, these results were shown to dependent on the presence of the solvent DMSO, which was used to dissolve APAP in the previous study (Masson et al., 2008). DMSO can activate and recruit NK and NKT cells; however, in the absence of DMSO, depletion of NK and NKT cells did not affect APAP-induced liver injury (Massson et al., 2008). A study using female mice with specific deletion of NKT cells (CD1d−/− and Jα18−/−) showed higher injury in response to APAP overdose at 24-48 h (Martin-Murphy et al., 2013). The increased susceptibility of the NKT cell-deficient mice was caused by increased levels of ketone bodies in the fasted KO mice, which triggered a mitochondrial oxidant stress even before APAP administration and rendered animals more susceptible to a second insult (e.g. APAP). In addition, the NKT cell-deficient mice showed higher levels of Cyp2E1 and protein adducts after APAP (Martin-Murphy et al., 2013). Although these finding can explain the higher susceptibility of the NKT cell-deficient mice to APAP overdose, it remains unclear why there was no difference during the early injury phase (8 h) but only during the later time points (24-48 h) (Martin-Murphy et al., 2013). When the same Jα18−/− mice were used in a different study, the NKT cell-deficient mice showed a profound protection against APAP toxicity between 4 and 24 h (Downs et al., 2012). The protection was associated with higher hepatic GSH levels in Jα18−/− mice resulting in higher detoxification of NAPQI and more effective scavenging of reactive oxygen/reactive nitrogen species (Down et al., 2012). This suggested that NKT cells attenuate hepatic GSH synthesis and thereby modulate APAP metabolism. Although the results of Downs et al. (2012) with the same NKT cell-deficient mice as Martin-Murphy et al., (2013) are opposite, there are differences in the experimental design. Downs et al. (2012) used fed male mice as compared to starved female mice in the Martin-Murphy study, which showed the excessive ketone body formation and mitochondrial dysfunction during starvation (Martin-Murphy et al., 2013). Together, these reports show variable results with depletion of NK and NKT cells against APAP hepatotoxicity in mice. Some of these variations may be caused by the experimental conditions. Interestingly, depletion of NKT cells can affect mitochondrial function and metabolic activation of APAP by modulating Cyp2E1 and hepatic GSH levels in hepatocytes. This emphasizes the need to study drug metabolism and other intracellular events when manipulating the immune system.

4. Cytokines and Chemokines

The roles of numerous cytokines and chemokines have been investigated in APAP hepatotoxicity models with variable results. A few selected examples will be discussed.

4.1. TNF-α and Interleukin-1α/β

Elevated levels of TNF-α and interleukin-1α/β have been reported in the mouse model of APAP hepatotoxicity (Blazka et al., 1995; Lawson et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2010b; Zhang et al., 2018) although the extent of this increase in circulating cytokines is variable. An initial study using neutralizing anti-serum suggested that eliminating TNF-α in circulation may only delay APAP-induced liver injury whereas polyclonal antibodies against IL-1α showed a significant reduction of injury (Blazka et al., 1995). A limitation of anti-sera or polyclonal antibodies as used in this early study is that these reagents can be contaminated with traces of endotoxin, which can be the cause of protection by downregulating cytochrome P450 enzymes (Liu et al., 2000). In addition, no appropriate control anti-sera were used. This raises some concerns regarding these results. A follow-up study observed no protection with anti-TNF antibodies or soluble TNF receptors against APAP toxicity (Simpson et al., 2000). Likewise, when mice deficient in TNF-α were used, no protection against APAP toxicity was observed during the first 8 h (Boess et al., 1998). Furthermore, mice deficient in the TNF receptor type I (C57Bl/6 background) showed increased APAP toxicity compared to wildtype animals mainly due to reduced antioxidant gene expression suggesting a role of TNF-α in down-regulating hepatic GSH synthesis and heme oxygenase-1 and SOD expression (Chiu et al., 2003a). In contrast, TNFR1−/− mice on a BALB/c background were partially protected against APAP hepatotoxicity by downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Ishida et al., 2004). A third study showed no effect of TNFR1-deficiency on APAP-induced liver injury (James et al., 2005a). Furthermore, mice with functionally inactive p50 subunits of NF-kB experienced reduced TNF-α expression in response to APAP overdose but no effect on the injury (Dambach et al., 2006). The reasons for the discrepancies are unclear but may be caused by variable sensitivities to inflammatory responses in different mouse strains or a sub-strain mismatch between wildtype and KO mice when both were purchased from different sources (Duan et al., 2016). In contrast, TNFR1 KO mice showed delayed regeneration after APAP-induced liver injury (Chiu et al., 2003b; James et al., 2005a). Activation of STAT3, a regulator of hepatocyte proliferation, was attenuated in TNFR1 KO mice (Chiu et al., 2003b). Thus, most of the presented data suggest that TNF-α is less involved in the frequently invoked inflammatory injury mechanisms by leukocytes but seems to regulate more intracellular defense mechanisms and repair responses in hepatocytes, which may be a beneficial effect in the pathophysiology.

Interleukin-1β received significant attention because it does not only require the transcriptional induction to form pro-IL-1β but also needs the activation of the inflammasome and caspase-1, which can cleave the pro-form to the active cytokine (Sutterwalla et al., 2006; Van de Veerdonk et al., 2011). Deficiency of TLR9 prevented pro-IL-1β formation and deficiencies of various inflammasome components including ASC, Nalp3 and caspase-1 attenuated IL-1β formation (Imaeda et al., 2009). Although the caspase-1-dependent formation of IL-1β could be confirmed, the amount of IL-1β formed during APAP toxicity is minimal and certainly below levels that could affect neutrophil activation in both mice (Williams et al., 2010b) and humans (Woolbright and Jaeschke, 2017b). In addition, neither IL-1 receptor-deficient mice (Williams et al., 2010b) nor mice lacking inflammasome genes including ASC, Nalp3 and caspase-1 (Williams et al., 2011) were protected. Consistent with these data, pan-caspase inhibitors do not protect against APAP toxicity (Lawson et al., 1999; Jaeschke et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2010b). Together these findings suggest that minor amounts of IL-1β are formed during APAP hepatotoxicity, but these low levels are insufficient to impact the toxicity.

A more recent study confirmed the low levels and limited relevance of IL-1β but suggest that IL-1α instead is more important in APAP toxicity (Zhang et al., 2018). Deletion of IL-1α but not IL-1β was protective (Zhang et al., 2018). In addition, IL-1R KO mice were protected (Zhang et al., 2018) in contrast to a previous report (Williams et al., 2010b). Also, the authors again rely on the questionable long-term neutropenia experiments to conclude that IL-1α promotes a neutrophil-mediated injury. Again, the reason for the discrepancies to the previous literature are unclear and our own measurements of IL-1α in human APAP overdose patients showed no relevant increase in surviving and non-surviving patients (Jaeschke, unpublished). Thus, the relevance of IL-1α in APAP toxicity is not more convincing than that of IL-1β.

4.2. Other Interleukins

IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by γδT cells, a subset of T helper cells (Beringer and Miossec, 2018). During APAP toxicity, IL-17 is generated in both mice (Zhu and Uetrecht, 2013) and humans (Li et al., 2010). IL-17A-deficient mice or animals treated with a neutralizing antibody against IL-17A were partially protected against APAP hepatotoxicity (Wang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2018). It was suggested that DAMPs like HMGB1 from necrotic hepatocytes induce IL-23 formation by Kupffer cells through TLR4; IL-23 activates the γδT cells to produce IL-17, which then recruit neutrophils (Wang et al., 2013). Because removal of IL-17 reduced neutrophil recruitment into the liver and attenuated the injury, it was concluded that IL-17 acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator that promotes liver injury through neutrophil toxicity (Lee et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2013). However, the conclusions are based on observations at a single, late time point and do not consider effects on intracellular signaling events, which could be relevant as direct interventions against neutrophils do not support their role in the toxicity (Williams et al., 2010a, 2014).

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine formed by Kupffer cells, monocytes and many other leukocytes. One of its main function is to suppress the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Stordeur and Goldman, 1998). IL-10 mRNA and protein are generated in mice and humans after an APAP overdose (Antoniades et al., 2012; Cover et al., 2006; Bourdi et al., 2002). Deficiency of the IL-10 gene triggers enhanced cytokine formation (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1α) and iNOS expression, which correlates with the higher injury after APAP (Bourdi et al., 2002). This increased liver injury is eliminated in IL-10/iNOS double KO mice suggesting that IL-10 formation limits the pro-inflammatory cytokine-mediated iNOS induction and peroxynitrite formation linking these cytokines to the modulation of intracellular mechanisms of toxicity (Bourdi et al., 2002). In APAP overdose patients, a mild increase in plasma IL-10 levels has been observed, however, there was no correlation between IL-10 concentrations and severity of liver injury (James et al., 2005b). These findings are in contrast to our own preliminary data. We observed substantially higher IL-10 levels in patients with severe APAP-induced liver injury compared to overdose patients with no relevant injury at admission to the hospital, i.e. within 24 h after taking an overdose (Woolbright et al., 2016). In studies with acute liver failure patients, which included 65% APAP overdose patients, elevated levels of IL-10 were observed although these levels were not different from decompensated cirrhosis patients (Berry et al., 2010). Interestingly, higher IL-10 levels at admission predicted poor outcome in all acute liver failure patients and specifically the APAP overdose patients (Berry et al., 2010). The findings with acute liver failure patients were interpreted to reflect a compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (Berry et al., 2010), which involves immunoparesis and monocyte deactivation (Bone et al., 1997). However, events during the acute injury after APAP overdose are distinct from the later events occurring during acute liver failure.

Another member of the IL-10 family of cytokines is IL-22, which can be generated by a number of immune cells including NK and NKT cells (Wolk et al., 2010). IL-22 does not act on other immune cells but affects epithelial cells and hepatocytes where it can protect against cell injury and promote regeneration (Wolk et al., 2010). Consistent with this hypothesis, treatment of mice with APAP and recombinant murine IL-22 (140 μg/kg, iv) showed reduced liver injury at 24 h but not at 6 h after APAP (Scheiermann et al., 2013). The protective effect of IL-22 correlated with reduced TNF-α formation, and increased STAT3 activation and higher numbers of Ki-67-positive cells in the liver suggesting a potential beneficial effect due to enhanced regeneration (Scheiermann et al., 2013). In a follow-up study, a single dose of murine IL-22 of 1 mg/kg effectively protected against 300 mg/kg APAP at 6 and 24 h (Feng et al., 2014). The protection was entirely dependent on STAT3 (Feng et al., 2014). However, transgenic mice who chronically generated high levels of IL-22 experienced a substantial exaggeration of APAP-induced liver injury compared to wild type animals. This enhanced injury was caused by increased levels of Cyp2E1 triggering enhanced protein adduct formations (Feng et al., 2014). Thus, acute versus chronic IL-22 treatment shows opposite effects in the APAP hepatotoxicity model due to promotion of regeneration and induction of metabolic activation, respectively. More recent studies also indicated that IL-22 can reduce APAP-induced oxidant stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (Chen et al., 2017) and promote autophagy (Mo et al., 2018). Together, these studies support the hypothesis that IL-22 acts on intracellular signaling mechanisms that limit cell death and promote recovery.

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

There is consensus in the literature that APAP-induced hepatic necrosis triggers a sterile inflammatory response. Although some mechanistic details may still be lacking, the overall mechanisms involving release of DAMPs from necrotic cells, the binding of various DAMPs to pattern recognition receptors on macrophages with formation of cytokines and chemokines and recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes into the liver is undisputed. However, the main controversy is the question whether this sterile inflammatory response, especially recruitment of leukocytes such as neutrophils and monocyte-derived macrophages, contribute to a late phase of injury or if they are strictly involved in the clean-up of cell debris and promotion of regeneration. When studies are considered that directly modulate the recruitment and cytotoxicity of neutrophils and monocytes, there is very little evidence that these leukocytes contribute to the injury phase. In contrast, there is strong support for the involvement of monocyte-derived macrophages, which are matured after hepatic recruitment into a pro-regenerative phenotype with increased phagocytosis capacity and expression of anti-inflammatory genes. Most studies in favor of an inflammatory injury mechanism show predominantly correlations between injury and leukocyte numbers and do not address the fundamental question of cause versus effect. In addition, studies that show a correlation between pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression and injury frequently assume that the cytokines work through leukocytes despite ample evidence that cytokines can influence other intracellular signaling events including drug metabolism, antioxidant defense and expression of other protective genes. Therefore, future studies aimed at advancing the field cannot just focus on a single inflammatory mediator and correlate this with liver injury. These studies need to consider the potential impact of these circulating mediators not only on various leukocyte populations but also on the intracellular mechanisms of cell death.

As outlined in this review there is not only a disagreement between investigators who favor an inflammatory injury component in the mechanism of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity and those who do not. Many “pro-inflammatory” studies contradict each other; however, this receives less attention. What are some of the potential reasons for these discrepancies? When comparing studies, it is not enough to just compare results but also examine how these results were obtained. It is known that different mouse strains show variable immune responses, which can lead to opposite results even with the same model (Galastri et al., 2012). The differential susceptibility of many mouse strains to APAP hepatotoxicity is well established, although this may be due to many factors including immune responses (Harrill et al., 2009). In addition, the differences in APAP-induced liver injury between sub-strains need to be considered, e.g. C57BL/6J versus C57BL/6N (Duan et al., 2016), which can lead to erroneous results if wild type and gene KO mice with a different substrain backgound are mismatched (Bourdi et al., 2011) or immune differences are not considered (Ulland et al., 2016).

Currently, most mechanistic studies involve one or more gene-deficient mice. The deletion of a gene can trigger adaptive mechanisms. Although some of these adaptations to the stress of a deleted gene can be substantial leading to obvious changes in the susceptibility to APAP (Ni et al., 2012), other adaptations may be more subtle and go un-detected unless one is specifically looking for them. Even acute versus chronic deletion of the same gene may trigger opposite results (Williams et al., 2015). Thus, off-target effects always need to be considered when using gene KO animals as one also should assume when using drugs or biological reagents. For example, it was concluded that benzyl alcohol protects against APAP overdose due to blocking TLR4 (Cai et al., 2014) but it mainly protected because it is also a P450 inhibitor (Du et al., 2015). As discussed, the anti-Gr-1 antibody triggers neutropenia but whether the off-target effect of inducing protective genes is relevant for the reduced liver injury depends on the time point of Gr-1 injection versus APAP administration (Jaeschke and Liu, 2007).

These examples show the many potential problems that can arise and influence the results when using the murine APAP model. There are many more including animal husbandry conditions and the diets, which determine the composition of the gut microbiome in these animals and the validation of the identity and purity of all reagents used in these experiments. Thus, in order to perform experiments that provide reliable and reproducible results, which will actually move the field forward instead of causing more confusion, it is necessary to understand and consider all aspects of the pathophysiology of APAP, including all potential pitfalls. This means that all intervention strategies including drugs, antibodies and use of gene knockout mice, need to be evaluated on their effect on the metabolic activation of APAP and the intracellular signaling mechanisms of cell death. It is also critical to realize that the pathophysiology involves several distinct phases, which means that instead of using only a single time point, it is essential to investigate events at several time points over a 24 h time period for the injury and up to 96 h when regeneration will be evaluated. It is also important to understand that a sterile inflammatory response starts with necrotic cell death, followed by the release of DAMPs, formation of cytokines and chemokines and ultimately the recruitment of leukocytes. Thus, an intervention that specifically acts during the inflammatory phase should not affect the injury at 6 h. If these basic experimental design issues are considered and the entire literature is taken into account, not just a few selected studies that fit the preconceived ideas, only then can we expect significant progress in our understanding of the role of inflammation in the injury and regeneration phases.

Acknowledgments

Work discussed in this review was supported in part by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants R01 NIDDK102142 and R01 NIDDK 070195, and National Institute of General Medicine (NIGMS) grants P20 GM103549 and P30 GM118247.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hartmut Jaeschke: Literature search, writing the original draft

Anup Ramachandran: edited the draft and designed the figure

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Al-Belooshi T, John A, Tariq S, Al-Otaiba A, Raza H, 2010. Increased mitochondrial stress and modulation of mitochondrial respiratory enzyme activities in acetaminophen-induced toxicity in mouse macrophage cells. Food Chem. Toxicol 48, 2624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine DJ, Jenkins RE, Dear JW, Williams DP, McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Craig DG, Simpson KJ, Jaeschke H, Park BK, 2012. Molecular forms of HMGB1 and keratin-18 as mechanistic biomarkers for mode of cell death and prognosis during clinical acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Hepatol 56, 1070–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Antoine DJ, Williams DP, Kipar A, Jenkins RE, Regan SL, Sathish JG, Kitteringham NR, Park BK, 2009. High-mobility group box-1 protein and keratin-18, circulating serum proteins informative of acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis in vivo. Toxicol. Sci 112, 521–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades CG, Khamri W, Abeles RD, Taams LS, Triantafyllou E, Possamai LA, Bernsmeier C, Mitry RR, O'Brien A, Gilroy D, Goldin R, Heneghan M, Heaton N, Jassem W, Bernal W, Vergani D, Ma Y, Quaglia A, Wendon J, Thursz M, 2014. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor: a pivotal mediator of anti-inflammatory responses in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology 59, 1564–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades CG, Quaglia A, Taams LS, Mitry RR, Hussain M, Abeles R, Possamai LA, Bruce M, McPhail M, Starling C, Wagner B, Barnardo A, Pomplun S, Auzinger G, Bernal W, Heaton N, Vergani D, Thursz MR, Wendon J, 2012. Source and characterization of hepatic macrophages in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in humans. Hepatology 56, 735–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Cover C, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H, 2006. Nuclear translocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor during acetaminophen-induced liver cell injury. Toxicol. Sci 94, 217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP, Spolarics Z, Jaeschke H, Smith CW, Spitzer JJ, 1994. Antineutrophil monoclonal antibody (1F12) alters superoxide anion release by neutrophils and Kupffer cells. J. Leukoc. Biol 55, 328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beringer A, Miossec P, 2018. IL-17 and IL-17-producing cells and liver diseases, with focus on autoimmune liver diseases. Autoimmun. Rev 17, 1176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry PA, Antoniades CG, Hussain MJ, McPhail MJ, Bernal W, Vergani D, Wendon JA, 2010. Admission levels and early changes in serum interleukin-10 are predictive of poor outcome in acute liver failure and decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 30, 733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, Walesky C, Manley M, Gallagher T, Borude P, Edwards G, Monga SP, Apte U, 2014. Pro-regenerative signaling after acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice identified using a novel incremental dose model. Am. J. Pathol 184, 3013–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi ME, 2007. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J. Leukoc. Biol 81, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilzer M, Roggel F, Gerbes AL, 2006. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver Int. 26, 1175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazka ME, Wilmer JL, Holladay SD, Wilson RE, Luster MI, 1995. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 133, 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boess F, Bopst M, Althaus R, Polsky S, Cohen SD, Eugster HP, Boelsterli UA, 1998. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in tumor necrosis factor/lymphotoxin-alpha gene knockout mice. Hepatology 27, 1021–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone RC, Grodzin CJ, Balk RA, 1997. Sepsis: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest 112, 235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdi M, Davies JS, Pohl LR, 2011. Mispairing C57BL/6 substrains of genetically engineered mice and wild-type controls can lead to confounding results as it did in studies of JNK2 in acetaminophen and concanavalin A liver injury. Chem. Res. Toxicol 24, 794–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdi M, Masubuchi Y, Reilly TP, Amouzadeh HR, Martin JL, George JW, Shah AG, Pohl LR, 2002. Protection against acetaminophen-induced liver injury and lethality by interleukin 10: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Hepatology 35, 289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Huang H, Whelan S, Liu L, Kautza B, Luciano J, Wang G, Chen G, Stratimirovic S, Tsung A, Billiar TR, Zuckerbraun BS, 2014. Benzyl alcohol attenuates acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in a Toll-like receptor-4-dependent pattern in mice. Hepatology 60, 990–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvente CJ, Tameda M, Johnson CD, Del Pilar H, Lin YC, Adronikou N, De Mollerat Du Jeu X, Llorente C, Boyer J, Feldstein AE, 2019. Neutrophils contribute to spontaneous resolution of liver inflammation and fibrosis via microRNA-223. J. Clin. Invest 130, 4091–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion SN, Johnson R, Aleksunes LM, Goedken MJ, van Rooijen N, Scheffer GL, Cherrington NJ, Manautou JE, 2008. Hepatic Mrp4 induction following acetaminophen exposure is dependent on Kupffer cell function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 295, G294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Zhang X, Fan J, Zai W, Luan J, Li Y, Wang S, Chen Q, Wang Y, Liang Y, Ju D, 2017. Tethering Interleukin-22 to Apolipoprotein A-I Ameliorates Mice from Acetaminophen-induced Liver Injury. Theranostics 26, 4135–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H, Gardner CR, Dambach DM, Brittingham JA, Durham SK, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, 2003a. Role of p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 in acetaminophen-induced antioxidant defense. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 285, G959–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H, Gardner CR, Dambach DM, Durham SK, Brittingham JA, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, 2003b. Role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (p55) in hepatocyte proliferation during acetaminophen-induced toxicity in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 193, 218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C, Liu J, Farhood A, Malle E, Waalkes MP, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H, 2006. Pathophysiological role of the acute inflammatory response during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 216, 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C, Mansouri A, Knight TR, Bajt ML, Lemasters JJ, Pessayre D, Jaeschke H, 2005. Peroxynitrite-induced mitochondrial and endonuclease-mediated nuclear DNA damage in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 315, 879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach DM, Durham SK, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, 2006. Distinct roles of NF-kappaB p50 in the regulation of acetaminophen-induced inflammatory mediator production and hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 211, 157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach DM, Watson LM, Gray KR, Durham SK, Laskin DL, 2002. Role of CCR2 in macrophage migration into the liver during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Hepatology 35, 1093–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F, Dal Ben D, Sarti AC, Giuliani AL, Falzoni S, 2017. The P2X7 Receptor in Infection and Inflammation. Immunity 47, 15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs I, Aw TY, Liu J, Adegboyega P, Ajuebor MN, 2012. Vα14iNKT cell deficiency prevents acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure by enhancing hepatic glutathione and altering APAP metabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 428, 245–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K, McGill MR, Xie Y, Jaeschke H, 2015. Benzyl alcohol protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes but causes mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death at higher doses. Food Chem. Toxicol 86, 253–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Davis JS, Woolbright BL, Du K, Cahkraborty M, Weemhoff J, Jaeschke H, Bourdi M, 2016. Differential susceptibility to acetaminophen-induced liver injury in sub-strains of C57BL/6 mice: 6N versus 6J. Food Chem. Toxicol 98, 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MJ, Keller BJ, Kauffman FC, Thurman RG, 1993. The involvement of Kupffer cells in carbon tetrachloride toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 119, 275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, Fisher MA, Farhood A, Manning AM, Smith CW, Jaeschke H, 1995. Cytokine-induced upregulation of hepatic intercellular adhesion molecule-1 messenger RNA expression and its role in the pathophysiology of murine endotoxin shock and acute liver failure. Hepatology 21, 1632–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Wang Y, Wang H, Weng H, Kong X, Martin-Murphy BV, Li Y, Park O, Dooley S, Ju C, Gao B, 2014. Acute and chronic effects of IL-22 on acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Immunol 193, 2512–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galastri S, Zamara E, Milani S, Novo E, Provenzano A, Delogu W, Vizzutti F, Sutti S, Locatelli I, Navari N, Vivoli E, Caligiuri A, Pinzani M, Albano E, Parola M, Marra F, 2012. Lack of CC chemokine ligand 2 differentially affects inflammation and fibrosis according to the genetic background in a murine model of steatohepatitis. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 123, 459–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao RY, Wang M, Liu Q, Feng D, Wen Y, Xia Y, Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Ju C, 2019. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-2α Reprograms Liver Macrophages to Protect Against Acute Liver Injury via the Production of Interleukin-6. Hepatology September 17. doi: 10.1002/hep.30954. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubardt N, Vugman M, Mouhadeb O, Caliari G, Pasmanik-Chor M, Reuveni D, Zigmond E, Brazowski E, David E, Chappell-Maor L, Jung S, Varol C, 2017. Ly6Chi Monocytes and Their Macrophage Descendants Regulate Neutrophil Function and Clearance in Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury. Front. Immunol 8, 626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H, 2003. Neutrophils aggravate acute liver injury during obstructive cholestasis in bile duct-ligated mice. Hepatology 38, 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Hinson JA, Farhood A, Jaeschke H, 2004. NADPH oxidase-derived oxidant stress is critical for neutrophil cytotoxicity during endotoxemia. Am., J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 287, G243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Knight TR, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H, 2002. Mode of cell death after acetaminophen overdose in mice: apoptosis or oncotic necrosis? Toxicol. Sci 67, 322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N, 2008. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Biol. Chem 283, 13565–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrill AH, Ross PK, Gatti DM, Threadgill DW, Rusyn I, 2009. Population-based discovery of toxicogenomics biomarkers for hepatotoxicity using a laboratory strain diversity panel. Toxicol. Sci 110, 235–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Malle E, Farhood A, Jaeschke H, 2005. Generation of hypochlorite-modified proteins by neutrophils during ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat liver: attenuation by ischemic preconditioning. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 289, G760–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Feng D, Li M, Gao Y, Ramirez T, Cao H, Kim SJ, Yang Y, Cai Y, Ju C, Wang H, Li J, Gao B, 2017. Hepatic mitochondrial DNA/Toll-like receptor 9/MicroRNA-223 forms a negative feedback loop to limit neutrophil overactivation and acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice. Hepatology 66, 220–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MP, Cheng L, Ju C, 2008. Identification and characterization of infiltrating macrophages in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Leukoc. Biol 84, 1410–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque R, Sohail MA, Salhanick S, Malik AF, Ghani A, Robson SC, Mehal WZ, 2012. P2X7 receptor-mediated purinergic signaling promotes liver injury in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 302, G1171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebener P, Pradere JP, Hernandez C, Gwak GY, Caviglia JM, Mu X, Loike JD, Schwabe RF, 2015. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J. Clin. Invest 125, 539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Mahmood S, Mohamadnejad M, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Mehal WZ, 2009. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J. Clin. Invest 119, 305–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Kondo T, Tsuneyama K, Lu P, Takayasu T, Mukaida N, 2004. The pathogenic roles of tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol 75, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Bethea NW, Abril ER, McCuskey RS, 2003. Early hepatic microvascular injury in response to acetaminophen toxicity. Microcirculation 10, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, 2006. Mechanisms of Liver Injury. II. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced liver cell injury during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion and other acute inflammatory conditions. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 290, G1083–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, 2011. Reactive oxygen and mechanisms of inflammatory liver injury: Present concepts. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 26 Suppl 1, 173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Akakpo JY, Umbaugh DS, Ramachandran A, 2020. Novel therapeutic approaches against acetaminophen-induced liver injury and acute liver failure. Toxicol. Sci January 11. pii: kfaa002. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa002. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Cover C, Bajt ML, 2006. Role of caspases in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Life Sci 78, 1670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Bautista AP, Spolarics Z, Spitzer JJ, Smith CW, 1993. Functional inactivation of neutrophils with a Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) monoclonal antibody protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat liver. Hepatology 17, 915–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Fisher MA, Smith CW, 1996. Sequestration of neutrophils in the hepatic vasculature during endotoxemia is independent of beta 2 integrins and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Shock 6, 351–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Smith CW, 1990. Neutrophils contribute to ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat liver in vivo. FASEB J 4, 3355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Liu J, 2007. Neutrophil depletion protects against murine acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: another perspective. Hepatology 45, 1588–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Ramachandran A, Chao X, Ding WX, 2019. Emerging and established modes of cell death during acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Arch. Toxicol 93, 3491–3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Smith CW, 1997. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J. Leukoc. Biol 61, 647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Ramachandran A, Bajt ML, 2012. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and repair: the role of sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Liver Int. 32, 8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, Kurten RC, Lamps LW, McCullough S, Hinson JA, 2005a. Tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 and hepatocyte regeneration in acetaminophen toxicity: a kinetic study of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and cytokine expression. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 97, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, McCullough SS, Knight TR, Jaeschke H, Hinson JA, 2003. Acetaminophen toxicity in mice lacking NADPH oxidase activity: role of peroxynitrite formation and mitochondrial oxidant stress. Free Radic. Res 37, 1289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, Simpson PM, Farrar HC, Kearns GL, Wasserman GS, Blumer JL, Reed MD, Sullivan JE, Hinson JA, 2005b. Cytokines and toxicity in acetaminophen overdose. J. Clin. Pharmacol 45, 1165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Reilly TP, Bourdi M, Radonovich MF, Brady JN, George JW, Pohl LR, 2002. Protective role of Kupffer cells in acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol 15, 1504–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlmark KR, Tacke F, Dunay IR, 2012. Monocytes in health and disease - Minireview. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp) 2, 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Son M, Lee SE, Park IH, Kwak MS, Han M, Lee HS, Kim ES, Kim JY, Lee JE, Choi JE, Diamond B, Shin JS, 2018. High-Mobility Group Box 1-Induced Complement Activation Causes Sterile Inflammation. Front. Immunol 9, 705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klune JR, Dhupar R, Cardinal J, Billiar TR, Tsung A, 2008. HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling. Mol. Med 14, 476–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Jaeschke H, 2002. Peroxynitrite formation and sinusoidal endothelial cell injury during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Comp. Hepatol 3 Suppl 1, S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ., 2004. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology 40, 1170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono H, Chen CJ, Ontiveros F, Rock KL, 2010. Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice. J. Clin. Invest 120, 1939–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P, Mehal WZ, 2012. Sterile inflammation in the liver. Gastroenterology 143, 1158–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin DL, Gardner CR, Price VF, Jollow DJ, 1995. Modulation of macrophage functioning abrogates the acute hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen. Hepatology 21, 1045–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin DL, Pilaro AM, 1986. Potential role of activated macrophages in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. I. Isolation and characterization of activated macrophages from rat liver. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 86, 204–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Farhood A, Hopper RD, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H, 2000. The hepatic inflammatory response after acetaminophen overdose: role of neutrophils. Toxicol. Sci 54, 509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Fisher MA, Simmons CA, Farhood A, Jaeschke H, 1999. Inhibition of Fas receptor (CD95)-induced hepatic caspase activation and apoptosis by acetaminophen in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 156, 179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC, Liao CC, Day YJ, Liou JT, Li AH, Liu FC, 2018. IL-17 deficiency attenuates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicol. Lett 292, 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levada K, Guldiken N, Zhang X, Vella G, Mo FR, James LP, Haybaeck J, Kessler SM, Kiemer AK, Ott T, Hartmann D, Hüser N, Ziol M, Trautwein C, Strnad P, 2018. Hsp72 protects against liver injury via attenuation of hepatocellular death, oxidative stress, and JNK signaling. J. Hepatol 68, 996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhang T, Zhou L, Zhou L, Xing G, Chen Y, Xin Y, 2014. Schisandrin B attenuates acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury through heat-shock protein 27 and 70 in mice. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 29, 640–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhu X, Liu F, Cai P, Sanders C, Lee WM, Uetrecht J, 2010. Cytokine and autoantibody patterns in acute liver failure. J. Immunotoxicol 7, 157–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew PX, Kubes P, 2019. The Neutrophil's Role During Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev 99, 1223–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, McGuire GM, Fisher MA, Farhood A, Smith CW, Jaeschke H, 1995. Activation of Kupffer cells and neutrophils for reactive oxygen formation is responsible for endotoxin-enhanced liver injury after hepatic ischemia. Shock 3, 56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZX, Govindarajan S, Kaplowitz N, 2004. Innate immune system plays a critical role in determining the progression and severity of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterology 127, 1760–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZX, Han D, Gunawan B, Kaplowitz N, 2006. Neutrophil depletion protects against murine acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology 43, 1220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Sendelbach LE, Parkinson A, Klaassen CD, 2000. Endotoxin pretreatment protects against the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen and carbon tetrachloride: role of cytochrome P450 suppression. Toxicology 147, 167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques PE, Amaral SS, Pires DA, Nogueira LL, Soriani FM, Lima BH, Lopes GA, Russo RC, Avila TV, Melgaço JG, Oliveira AG, Pinto MA, Lima CX, De Paula AM, Cara DC, Leite MF, Teixeira MM, Menezes GB, 2012. Chemokines and mitochondrial products activate neutrophils to amplify organ injury during mouse acute liver failure. Hepatology 56, 1971–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques PE, Oliveira AG, Pereira RV, David BA, Gomides LF, Saraiva AM, Pires DA, Novaes JT, Patricio DO, Cisalpino D, Menezes-Garcia Z, Leevy WM, Chapman SE, Mahecha G, Marques RE, Guabiraba R, Martins VP, Souza DG, Mansur DS, Teixeira MM, Leite MF, Menezes GB, 2015. Hepatic DNA deposition drives drug-induced liver injury and inflammation in mice. Hepatology 61, 348–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Murphy BV, Holt MP, Ju C, 2010. The role of damage associated molecular pattern molecules in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol. Lett 192, 387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Murphy BV, Kominsky DJ, Orlicky DJ, Donohue TM Jr, Ju C, 2013. Increased susceptibility of natural killer T-cell-deficient mice to acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Hepatology 57, 1575–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson MJ, Carpenter LD, Graf ML, Pohl LR, 2008. Pathogenic role of natural killer T and natural killer cells in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice is dependent on the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. Hepatology 48, 889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Jaeschke H, 2013. Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis. Pharm. Res 30, 2174–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Williams CD, Taha M, Curry SC, Jaeschke H, 2012a. The mechanism underlying acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Clin. Invest 122, 1574–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Williams CD, Xie Y, Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H, 2012b. Acetaminophen-induced liver injury in rats and mice: comparison of protein adducts, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in the mechanism of toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 264, 387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael SL, Pumford NR, Mayeux PR, Niesman MR, Hinson JA, 1999. Pretreatment of mice with macrophage inactivators decreases acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Hepatology 30, 186–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo R, Lai R, Lu J, Zhuang Y, Zhou T, Jiang S, Ren P, Li Z, Cao Z, Liu Y, Chen L, Xiong L, Wang P, Wang H, Cai W, Xiang X, Bao S, Xie Q, 2018. Enhanced autophagy contributes to protective effects of IL-22 against acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Theranostics 8, 4170–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossanen JC, Krenkel O, Ergen C, Govaere O, Liepelt A, Puengel T, Heymann F, Kalthoff S, Lefebvre E, Eulberg D, Luedde T, Marx G, Strassburg CP, Roskams T, Trautwein C, Tacke F, 2016. Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2-positive monocytes aggravate the early phase of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Hepatology 64, 1667–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HM, Boggess N, McGill MR, Lebofsky M, Borude P, Apte U, Jaeschke H, Ding WX, 2012. Liver-specific loss of Atg5 causes persistent activation of Nrf2 and protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci 127, 438–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Matsura T, Nakada J, Togawa A, Kai M, Sumioka I, Minami Y, Inagaki Y, Ishibe Y, Ito H, Ohta Y, Yamada K, 2006. Geranylgeranylacetone protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by inducing heat shock protein 70. Toxicology 219, 187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SJ, Luther J, Bohr S, Iracheta-Vellve A, Li M, King KR, Chung RT, Yarmush ML, 2016. A Novel Resolvin-Based Strategy for Limiting Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol 7, e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopowicz Z, Marcinkiewicz J, Katz DR, Chain BM, 2012. Neutrophil myeloperoxidase: soldier and statesman. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 60, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H, 2019. Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. Semin. Liver Dis 39, 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh JS, Sohn DH, 2018. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune Netw. 18, e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H, 2010a. c-Jun N-terminal kinase modulates oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation independent of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 246, 8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C, Yan HM, Artigues A, Villar MT, Farhood A, Jaeschke H, 2010b. Mechanism of protection by metallothionein against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 242, 182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen WF Jr, Voellmy R, Roberts SM, 1997. Differential heat shock protein induction by acetaminophen and a nonhepatotoxic regioisomer, 3'-hydroxyacetanilide, in mouse liver. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 282, 1533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME, 2002. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418, 191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiermann P, Bachmann M, Goren I, Zwissler B, Pfeilschifter J, Mühl H, 2013. Application of interleukin-22 mediates protection in experimental acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Am. J. Pathol 182, 1107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Filardi E, Nieto C, Domínguez-Soto A, Barroso R, Sánchez-Mateos P, Puig-Kroger A, López-Bravo M, Joven J, Ardavín C, Rodríguez-Fernández JL, Sánchez-Torres C, Mellado M, Corbí AL, 2014. CCL2 shapes macrophage polarization by GM-CSF and M-CSF: identification of CCL2/CCR2-dependent gene expression profile. J. Immunol 192, 3858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]