Abstract

Background

Faecal incontinence (leakage of bowel motions or stool) is a common symptom which causes significant distress and reduces quality of life.

Objectives

To assess the effects of drug therapy for the treatment of faecal incontinence. In particular, to assess the effects of individual drugs relative to placebo or other drugs, and to compare drug therapy with other treatment modalities.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register of Trials, which contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and MEDLINE in process, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings (searched 21 June 2012) and the reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

All randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials were included in this systematic review.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened abstracts, extracted data and assessed risk of bias of the included trials.

Main results

Sixteen trials were identified, including 558 participants. Eleven trials were of cross‐over design. Eleven trials included only people with faecal incontinence related to liquid stool (either chronic diarrhoea, following ileoanal pouch or rectal surgery, or due to use of a weight‐reducing drug). Two trials were amongst people with weak anal sphincters, one in participants with faecal impaction and bypass leakage, and one in geriatric patients. In one trial there was no specific cause for faecal incontinence.

Seven trials tested anti‐diarrhoeal drugs to reduce faecal incontinence and other bowel symptoms (loperamide, diphenoxylate plus atropine, and codeine). Six trials tested drugs that enhance anal sphincter function (phenylepinephrine gel and sodium valproate). Two trials evaluated osmotic laxatives (lactulose) for the treatment of faecal incontinence associated with constipation in geriatric patients. One trial assessed the use of zinc‐aluminium ointment for faecal incontinence. No studies comparing drugs with other treatment modalities were identified.

There was limited evidence that antidiarrhoeal drugs and drugs that enhance anal sphincter tone may reduce faecal incontinence in patients with liquid stools. Loperamide was associated with more adverse effects (such as constipation, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, headache and nausea) than placebo. However, the dose may be titrated to the patient's symptoms to minimise side effects while achieving continence. The drugs acting on the sphincter sometimes resulted in local dermatitis, abdominal pain or nausea. Laxative use in geriatric patients reduced faecal soiling and the need for help from nurses.

Zinc‐aluminium ointment was associated with improved quality of life, with no reported adverse effects. However, the observed improvement in quality of life was seen in the placebo group as well as the treatment group.

It should be noted that all the included trials in this review had small sample sizes and short duration of follow‐up. 'Risk of bias' assessment was unclear for most of the domains as there was insufficient information. There were no data suitable for meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

The small number of trials identified for this review assessed several different drugs in a variety of patient populations. The focus of most of the included trials was on the treatment of diarrhoea, rather than faecal incontinence. There is little evidence to guide clinicians in the selection of drug therapies for faecal incontinence. Larger, well‐designed controlled trials, which use the recommendations and principles set out in the CONSORT statement, and include clinically important outcome measures, are required.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Antidiarrheals, Antidiarrheals/therapeutic use, Diarrhea, Diarrhea/drug therapy, Epinephrine, Epinephrine/therapeutic use, Fecal Incontinence, Fecal Incontinence/drug therapy, Gastrointestinal Agents, Gastrointestinal Agents/therapeutic use, Lactulose, Lactulose/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Valproic Acid, Valproic Acid/therapeutic use, Zinc Compounds, Zinc Compounds/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Drug treatment for faecal incontinence in adults

Faecal incontinence (inability to control bowel movements or leakage of stool or faeces) is a common healthcare problem, affecting up to one in 10 of adults living at home. This affects daily activities in about one or two in 100 people. It is more common in people living in residential care. Leakage of urine often occurs as well. Faecal incontinence can be debilitating and embarrassing. Treatments include pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, surgery and drugs. This review looked at drugs for the treatment of faecal incontinence. These included anti‐diarrhoea drugs or laxatives to regulate stools, and drugs to try to enhance the tone of muscle around the anus which help to keep it closed. Sixteen small trials were found, including 558 participants. The review of these trials found some evidence that anti‐diarrhoea drugs may reduce faecal incontinence for people having liquid stools. However, these drugs were associated with some side effects. There was some evidence that drugs to enhance the tone of the muscle around the anus may help, but more research is needed.

Background

Faecal incontinence may be defined as the involuntary loss of solid or liquid faeces (Maeda 2013). It is a common healthcare problem, and its prevalence may range from 1.6% to 15% depending on the definition used, the age of patients and whether patients are community‐dwelling or living in an institution (Maeda 2013; Whitehead 2009). The real prevalence of faecal incontinence is likely to be even higher than reported as the social stigma associated with faecal incontinence means patients are reluctant to seek help due to embarrassment (Deutekom 2012). Faecal incontinence is a distressing symptom for patients; it has a major negative impact on quality of life and activities of daily living, and is often accompanied by severe social restriction (Perry 2002; Rockwood 2000).

Description of the condition

Faecal incontinence may occur passively, where there is involuntary loss of faeces without urge to defecate, or may be preceded by urgency, where there is loss of faeces following inability to resist the urge to defecate for long enough to reach the toilet (Mowatt 2007; Maeda 2013). Faecal incontinence has a range of possible causes. The maintenance of continence is reliant on a number of interacting factors which include an intact and functional anal sphincter complex, the consistency of faeces, adequate cognitive and physical ability, and bowel motility. The impairment of any of these elements may lead to incontinence (Maeda 2013).

Faecal incontinence may occur due to damage to the anal sphincter mechanism following anal surgery such as anal dilatation, sphincterotomy, fistula surgery or haemorrhoidectomy (Lindsey 2004; Maeda 2013). Trauma to the anal sphincter may also occur during childbirth with third or fourth degree vaginal tears (Maeda 2013; Wheeler 2007). Dysfunction of the anal sphincters may occur without structural damage in cases of primary degeneration, systemic disease such as systemic sclerosis, or due to damage of the myenteric plexus following radiotherapy (Da Silva 2003; Maeda 2013; Vaizey 1997). In addition to this, faecal incontinence may occur due to spinal injury or other neurological disease causing sensory or motor impairment to the continence mechanism, or due to rectal loading and subsequent overflow leakage in frail or immobile individuals, or due to physical or mental disability affecting toilet habits (Norton 2012). Moreover, in many cases faecal incontinence occurs due to the combination of structural, physiological and psycho‐social factors (Rao 2004; Tuteja 2004)

The management of faecal incontinence varies according to the underlying disorder, the impact of the problem on the patient's quality of life and the available resources. However, for many conditions, the treatment options are limited, relying mainly on surgery and constipating drugs (Madoff 2009; Norton 2012; Whitehead 2001).

Treatment options include:

(i) Conservative Treatment

Conservative options include pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, dietary modification, use of pads and plug devices. Previously published Cochrane reviews have considered these modalities (Deutekom 2012; Fader 2009; Norton 2012)

(ii) Surgical Treatment

Surgical options include sphincter repair, neo‐sphincter formation, formation of colostomy or stoma, the antegrade continent enema (ACE) procedure and newer techniques such as injection augmentation and implanted sacral nerve stimulation. Previously published Cochrane reviews have considered these modalities (Brown 2010; Maeda 2013; Mowatt 2007).

(iii) Medical Treatment

Medical treatment options include the use of constipating agents and laxatives, and these drugs are the subject of this review and are discussed below. Other medical treatment options include evacuation aids and stool bulking agents but these options are not considered within this review.

Description of the intervention

Constipating agents

Constipating agents include loperamide, codeine phosphate and co‐phenotrope. Loperamide is the most common drug due to its low side‐effect profile (Gattuso 1994). Initially, small doses (e.g. 2 mg to 4 mg daily) are titrated according to clinical symptom response. Liquid formulations are available if even lower doses are needed. People with liquid stool (for example following ileoanal pouch surgery) may require much higher doses. Codeine phosphate is used in a similar way, but side effects such as drowsiness may limit its use. In unresponsive cases the combined use of both loperamide and codeine phosphate may be useful. Co‐phenotrope (a proprietary mixture of diphenoxylate with atropine) is not favoured due to the high incidence of side effects, particularly those related to the atropine component.

Laxatives

Laxative treatment (e.g. lactulose, a galactose‐fructose disaccharide) is used most often in elderly people, to treat faecal incontinence associated with constipation or faecal impaction.

Drugs acting on anal sphincter tone

Drugs which act on the anal sphincter may have an important role to play in the treatment of patients with faecal incontinence, especially in those with nocturnal symptoms (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #). Phenylephrine gel, an alpha1‐adrenergic agonist, is applied topically to the anal margin. Zinc‐aluminium ointment is applied topically to the anal canal mucosa (Pinedo 2012). Sodium valproate is an anticonvulsant medication which is usually taken orally for the treatment of a range of different psychiatric conditions, but may also have a contractile effect on the internal anal sphincter (Kusunoki 1990 #).

How the intervention might work

The mode of action of constipating agents, such as loperamide, is not completely understood but they may reduce faecal incontinence by increasing anal sphincter smooth muscle tone, reducing stool weight and small bowel motility, and by altering stool consistency so that it is less soft (Read 1982 #; Herbst 1998). Laxatives act to reduce symptoms in those who have bypass faecal incontinence secondary to constipation or faecal impaction (Chassagne 2000). Phenylephrine gel, sodium valproate and zinc‐aluminium ointment may reduce faecal incontinence by increasing the tone or contraction strength of the anal sphincter (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #, Kusunoki 1990 #; Pinedo 2012). There is evidence that aluminium can act to increase smooth muscle contraction by acting on the plasmatic membrane and inhibiting the influx of calcium ions in smooth muscle cells (Pinedo 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

This review aims to systematically search for and combine evidence from all relevant randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials on the effects of drug therapies (other than suppositories and enemas or fibre supplements) for the treatment of faecal incontinence in order to provide the best evidence on which to base recommendations for clinical practice and further research.

Objectives

To determine the effects of using drugs in the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. The following comparisons were made.

Drug treatment of faecal incontinence versus placebo (or no active treatment).

Drug treatment of faecal incontinence versus conservative treatments (such as physical therapies, lifestyle changes or diet).

Drug treatment of faecal incontinence versus surgical treatment.

Drug treatment in combination with surgical treatment versus surgical treatment alone.

One drug versus another drug or a combination of drugs in the treatment of faecal incontinence.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Cross‐over trials have been identified with the suffix '#'.

Types of participants

People over 18 years old with symptoms of faecal incontinence.

Types of interventions

At least one trial group treated with any type of drug (other than suppositories and enemas).

Comparison interventions may include placebo, conservative (physical) treatments, nutritional interventions, surgery, suppositories, enemas and other drugs.

Trials of suppositories, enemas or fibre supplements are excluded from this review.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes are concerned with reduction of patient symptoms of faecal incontinence such as cure or improvement, frequency of incontinence, effect on quality of life and use of pads.

Secondary endpoints include faecal urgency, frequency of defecation, stool weight or consistency, incontinence scores, adverse events, satisfaction with treatment, psychological parameters and economic measures. There are no objective measures of faecal incontinence.

Anorectal physiological measurements may not be directly comparable between trials due to the great variation in the technology and methods of assessing anorectal function in different clinical units. In addition, they may not be directly related to clinical outcomes. Therefore, these measures are considered only as surrogate endpoints.

1. Participant observations

Number of people failing to achieve complete continence

Number of people failing to improve

Frequency of incontinence (diary or self‐report)

Degree of incontinence (e.g. stool weight)

Number of pad changes

Incontinence score

Episodes of faecal urgency

2. Participant satisfaction

Self‐reported satisfaction with treatment

3. Clinician observations (anorectal physiological measurements)

Maximal resting anal canal pressure (pressure or EMG)

Duration of anal canal pressure during voluntary contraction

Rectal sensation (by balloon insufflation or electrical stimulation)

Magnitude of fall in resting anal pressure during rectal distension (rectoanal inhibitory reflex)

Saline retention test

4. Adverse effects

Constipation, abdominal pain, headache and nausea.

5. Quality of life (health status measures)

Condition‐specific measures of effect of faecal incontinence on quality of life (for example, Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale, Rockwood 2000)

Psychological measures (for example, HADS, Zigmond 1983)

Generic health‐related quality of life measures (for example, Short Form 36 Profile, Ware 1993)

6. Socioeconomic measures

Costs of interventions

Cost‐effectiveness of interventions

7. Other outcome measures:

Any other outcome measure later judged important by the review authors

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on any of these searches.

Electronic searches

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Group's Specialised Register of controlled trials which is described under the Incontinence Group's module in The Cochrane Library. The register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and MEDLINE in process, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Date of the most recent search of the register for this review: 21 June 2012. The trials in the Incontinence Group's Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The terms used to search the Specialised Register are shown below:

({DESIGN.RCT.*} OR {DESIGN.CCT.*}) AND {TOPIC.FAECAL.*} AND (INTVENT.CHEM.DRUG.*} (All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 12, Thomson Reuters).

Searching other resources

The review authors also searched the reference lists of relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the original review, two review authors (MC, CN) examined all the citations and abstracts derived from the electronic search strategy and independently selected trials to be included in the first review, and CG updated this for the first update.

For this update, MO and CA independently screened all the abstracts generated from the updated search, conducted data extraction for the included trials and performed 'Risk of bias' assessment of all the trials in accordance with the current methodology. Review authors were not blinded to the names of the trials' authors, institutions or journals. Any disagreement about trial inclusion was resolved by discussion or arbitration.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted independently by at least two review authors. Results were compared and any difference of opinion discussed and reconciled amongst the review authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). This included:

sequence generation,

allocation concealment,

blinding of participants or therapists,

blinding of outcome assessors,

completeness of outcome data,

selective outcome reporting.

For cross‐over trials, the following additional domains were included in the 'other sources of bias':

Was use of a cross over design appropriate?

Is it clear that the order of receiving treatment was randomised?

Can it be assumed that the trial was not biased from carry‐over effects?

Two of the review authors (MO and CA) independently assessed these domains. Any differences of opinion were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third party.

Measures of treatment effect

Analyses were based on available data from all included trials relevant to the comparisons and outcomes of interest. For trials with multiple publications, only the most up‐to‐date or complete data for each outcome were included. Meta‐analysis could not be performed because of the variation in reported outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per participants randomised.

Dealing with missing data

The data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible, meaning that all participants were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised. If this was not the case, we considered whether the trial should be excluded. Attempts were made to obtain missing data from the original trialists. However, if this was not possible, data were reported as given in the studies, except if there was evidence of differential loss to follow‐up from the randomised groups. In that case, the use of imputation of missing data was considered.

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, the review authors aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

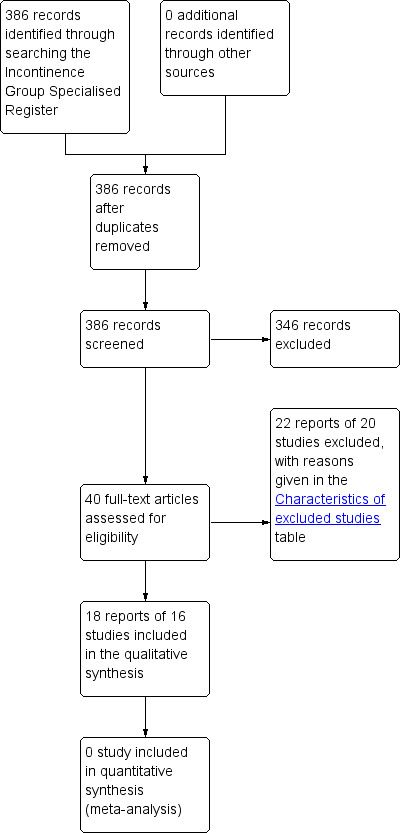

The literature search produced a total of 386 records to screen for this review. In this second update of this review, three new RCTs were included (Lumi 2009; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012). In the first update of this review, two new RCTs (Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #) were added and a further four studies were excluded (Bliss 2001; Christensen 2006; Harari 2004; Whitebird 2006). The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Included studies

Sixteen trials, published in 18 reports and including the three new RCTs, met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The total number of participants in the 16 trials was 558.

Design

Eleven trials were of cross‐over design (identified by a suffix # after the trial ID) and five had a parallel group design (Chassagne 2000; Lumi 2009; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012; Ryan 1974). Four of the cross‐over trials had short (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #) or no washout periods between treatments.

Setting

Fourteen trials were performed at single centres. Of these, seven were conducted in the United Kingdom and one was conducted in each of, Sweden, the USA, Australia, Argentina, South Korea, Chile and Japan. One of the other two trials was a multicentre RCT conducted in five long‐term care units in France, and the other recruited participants from the UK and Germany by advertisement.

Diagnosis

The participants had a variety of causes for their faecal incontinence:

Five trials included people who had previously undergone restorative proctocolectomy (ileoanal pouch formation) (Carapeti 2000b #; Cohen 2001 #; Hallgren 1994 #Kusunoki 1990 #; Lumi 2009).

One trial recruited participants with rectal cancer who had undergone low anterior resection Park 2007.

Four trials included people with chronic diarrhoea (Harford 1980 #; Palmer 1980 #; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) due to various medical conditions.

Two trials enrolled patients with passive faecal incontinence but structurally intact sphincters (Carapeti 2000a #; Cheetham 2001 #).

One trial assessed patients with faecal incontinence associated with faecal impaction or functional obstructed defecation (Chassagne 2000).

One trial evaluated geriatric patients but did not describe their symptoms or details of their medical history (Ryan 1974).

One trial was aimed at patients using an obesity treatment, orlistat, in order to decrease the unwanted bowel side effects of oily stools, faecal frequency, incontinence and possibly anal fissure (Fox 2005 #).

One trial recruited patients with faecal incontinence with no specified diagnosis (Pinedo 2012).

Intervention

Five trials tested anti‐diarrhoeal drugs to reduce faecal incontinence and other bowel symptoms.

Loperamide was compared with placebo for the treatment of faecal incontinence in two trials (Hallgren 1994 #; Read 1982 #).

Different doses of loperamide were compared in one trial (Fox 2005 #).

Two routes of administration of loperamide (oral versus suppository) were compared in another (Cohen 2001 #).

Loperamide oxide was compared with placebo in one trial (Sun 1997 #).

Diphenoxylate plus atropine (co‐phenotrope) was compared with placebo in another trial (Harford 1980 #).

One trial compared three anti‐diarrhoeal drugs: loperamide, codeine and diphenoxylate plus atropine (Palmer 1980 #).

Seven trials tested drugs enhancing anal sphincter function:

phenylepinephrine gel was compared with placebo in five trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #, Cheetham 2001 #; Lumi 2009; Park 2007);

sodium valproate was compared with placebo in another trial (Kusunoki 1990 #);

zinc‐aluminium ointment was compared with placebo in another trial (Pinedo 2012).

Endoanal ultrasound scanning was performed before inclusion in three of these trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #).

Two trials evaluated ways of using osmotic laxatives (lactulose) for the treatment of faecal incontinence associated with constipation in geriatric patients (Chassagne 2000; Ryan 1974).

Sample size

Sample size was small in most of the included trials. Eleven trials enrolled fewer than 50 participants. The largest trial included 178 participants and the smallest included 10 participants.

Length of treatment

All trials were of short duration. No trial provided long‐term results of treatment.

Costs

Only one trial considered the cost implications (related to money saved on laundry and nursing time) of treatment (Ryan 1974).

Further details of the included trials are given in the Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

In total 20 studies have been excluded from the review (see the Characteristics of excluded studies).

Three trials were excluded because they were not randomised controlled trials (Emblem 1989; Eogan 2007; Santos 1961);

seven because the intervention was not relevant (Bliss 2001; Christensen 2006; Freedman 1959; Harari 2004; Heymen 2004; Heymen 2004a; Whitebird 2006);

eight because participants did not have faecal incontinence (Drossman 2007; Grijalva 2010; Henriksson 1992; Qvitzau 1988; Rosman 2008; Schneiter 1972; Tu 2008; Van Assche 2012);

one trial because the results for faecal incontinence were not randomised (Shoji 1993).

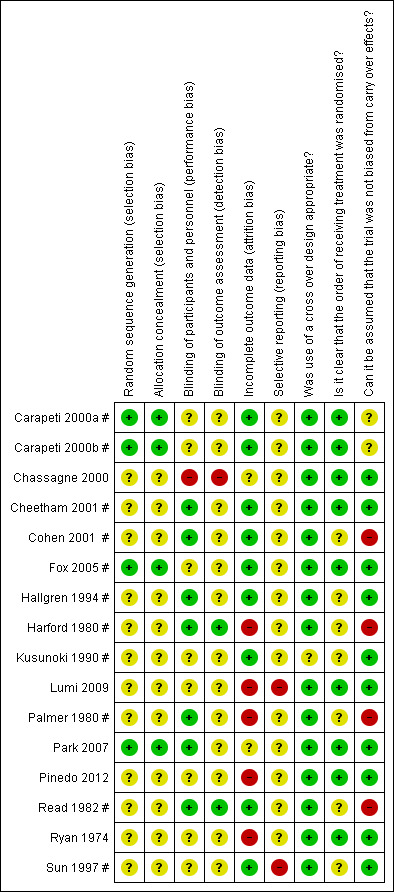

Risk of bias in included studies

In this systematic review we included 11 cross‐over trials and five randomised controlled trials.

Allocation

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment was unclear in 12/16 trials (Chassagne 2000; Cheetham 2001 #; Cohen 2001 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Lumi 2009; Palmer 1980 #; Pinedo 2012; Read 1982 #; Ryan 1974; Sun 1997 #). Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b # used a computer‐generated random numbers which was carried out by the hospital pharmacy. Fox 2005 # used a computer‐generated randomisation list, which was administered by the hospital pharmacy. Park 2007 used one‐to‐one randomisation code, which was derived by the pharmacy trials co‐ordinator using a computer‐generated random number sequence.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel was carried out in 6/16 trials (Cohen 2001 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Palmer 1980 #; Park 2007; Read 1982 #); was not carried out in 1/16 trials Chassagne 2000, and remained unclear in 9/16 trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #; Fox 2005 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Lumi 2009; Pinedo 2012; Ryan 1974; Sun 1997 #).

The blinding of outcome assessment was carried out in 2/16 trials (Harford 1980 #; Read 1982 #), was not carried out in 1/16 trials (Chassagne 2000), and remained unclear in 13/16 trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Lumi 2009; Palmer 1980 #; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012; Ryan 1974; Sun 1997 #).

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were complete in 11/16 of the included trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Chassagne 2000; Cheetham 2001 #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Park 2007; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #), but there were incomplete outcome data in the remaining five trials (Harford 1980 #; Lumi 2009; Palmer 1980 #; Pinedo 2012; Ryan 1974).

Selective reporting

The presence of selective reporting remained unclear in all 16 of the included trials because protocols were not available.

Other potential sources of bias

The use of a cross‐over design was appropriate in all of the 11 included cross‐over trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Palmer 1980 #; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #).

The order of treatment allocation was randomised in 4/11 of the cross‐over trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #; Fox 2005 #), but remained unclear in the remaining 7/11 cross‐over trials (Cohen 2001 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Palmer 1980 #; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #).

In 5/11 of the included cross‐over trials there was an adequate washout period and it could be assumed that bias had not been introduced from a carry‐over effect (Cheetham 2001 #; Fox 2005 #; Hallgren 1994 #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Sun 1997 #). However, in 4/11 of the included cross‐over trials there was not an adequate washout period between interventions; three of these provided no washout period (Harford 1980 #Palmer 1980 #; Read 1982 #) and one trial provided only a two‐day washout period (Cohen 2001 #). In 2/11 of the cross‐over trials a washout period of one week was provided, but it was unclear if this was sufficient to remove any potential carry‐over effect (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #).

Detailed results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment are provided in Figure 2; Figure 3,

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Data analysis

Eleven of the 16 included trials were of cross‐over design. All but two of these (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #) presented data for both active arm and placebo‐control arm at trial completion and did not provide data at the end of the first trial period. Four trials included between‐treatment washout periods (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #) but were not mentioned in the remainder. Furthermore, all included trials either used different drugs or included participants with very different medical conditions. For these reasons (clinical heterogeneity), it was not appropriate to formally meta‐analyse any of these data. Two trials did not provide any numerical data that could be included in data tables (Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #).

Effects of interventions

Data from the included trials are presented in Other Data Tables: either the data could not be combined because the interventions or reported outcomes varied between the studies, or they were cross‐over trials in which the data were not reported in a way that could be used in a meta‐analysis.

DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO OR NO‐ACTIVE TREATMENT (Other Data Tables 1)

Three main classes of drugs were tested in the included trials:

a) those with an anti‐diarrhoeal or constipating action,

b) those acting directly on the anal sphincter to enhance its tone, and

c) those which stimulate rectal emptying (laxatives).

A. Anti‐diarrhoeal/constipating agents versus placebo

Two trials tested loperamide versus placebo, one in people with ileoanal pouches (Hallgren 1994 #) and the other in people with chronic diarrhoea (Read 1982 #). One trial tested loperamide oxide (which is converted in the gut to loperamide) versus placebo in people with chronic diarrhoea (Sun 1997 #). One trial tested diphenoxylate plus atropine in people with chronic diarrhoea, not all of whom had regular faecal incontinence (Harford 1980 #). We did not find any trials of codeine phosphate versus placebo.

In these four trials, people were reported to be better on active drug than on placebo. In particular:

more people achieved full continence in three trials: (Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.1) and improved their incontinence symptoms in two trials: (Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.2);

there were fewer episodes of faecal incontinence in one trial: (Read 1982 #) (Analysis 1.3), faecal urgency in one trial: (Read 1982 #) (Analysis 1.2.1) and unformed stools (two trials: (Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.2);

people used fewer pads in one trial: (Hallgren 1994 #) (Analysis 1.7) and had lower faecal incontinence scores in one trial: (Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.5), fewer bowel actions per day in four trials: (Hallgren 1994 #; Harford 1980 #; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.4), lower stool weights in three trials: (Harford 1980 #; Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.6), and longer gut transit times in one trial: (Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.16).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Number of people failing to achieve full continence.

| Number of people failing to achieve full continence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Hallgren 1994 # | 3/28 during the day 1/28 during the night | 7/28 during the day 11/28 during the night | |

| Sun 1997 # | 4/11 in 24 hours (loperamide oxide) | 8/11 in 24 hours | P < 0.05 |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | |||

| Harford 1980 # | 0/15 in 24 hours | 3/15 in 24 hours | |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | |||

| Carapeti 2000b # | 8/12 | 12/12 | |

| Sodium valproate versus placebo | |||

| Kusunoki 1990 # | 3/17 | 10/17 | |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 2 Number of people failing to improve incontinence.

| Number of people failing to improve incontinence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Read 1982 # | Episodes of urgency: 7/26

Incontinence episodes: 19/26 Per cent unformed stool per week (mean, range): 40% (0%‐100%) |

Episodes of urgency: 23/26

Incontinence episodes: 24/26 Per cent unformed stool per week (mean, range): 57% (0%‐100%) (P < 0.001) |

| Sun 1997 # | No improvement in stool consistency: 2/11 Per cent of days with unformed stools: 33% (loperamide oxide) |

No improvement in stool consistency: 8/11 Per cent of days with unformed stools: 66% (P < 0.02) |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | ||

| Harford 1980 # | No improvement in stool weight and frequency: 3/15 | No improvement in stool weight and frequency: 3/15 |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | ||

| Carapeti 2000a # | No subjective improvement: 30/36 | 34/36 |

| Carapeti 2000b # | No undefined 'improvement': 6/12 | 11/12 |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 3 Number of faecal incontinence episodes.

| Number of faecal incontinence episodes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Read 1982 # | Mean 0.6 (range 0‐6) per week | Mean 0.9 (range 0‐6) |

| Phenylephrine cream versus placebo | ||

| Lumi 2009 | Median 5.4 (range 0‐14) |

Median 9 (range 0‐19) |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 7 Number of people using pads.

| Number of people using pads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Hallgren 1994 # | During the day: 1/28 During the night: 1/28 | During the day: 3/28 During the night: 6/28 |

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 5 Faecal incontinence score.

| Faecal incontinence score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Sun 1997 # | visual analogue incontinence scale: N 11 mean 26 (SD 36) loperamide oxide | N 11 mean 43 (SD 37) | P = 0.12 |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | |||

| Carapeti 2000a # | N 18 mean 12.5 (SD 3.4) | N 18 mean 12.6 (SD 4.2) | No significant difference |

| Carapeti 2000b # | N 12 mean 12.2 (SD 5.7) | N 12 mean 16.5 (SD 4.4) | |

| Park 2007 | Anal incontinence evaluated with Faecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) and reported as mean (SD) n = 17; Baseline: 32.5 (14.5); After: 32.3 (14.7) P = 0.940 |

Anal incontinence evaluated with Faecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) and reported as mean (SD) n = 12; Baseline: 32.1 (11.2); After: 32.4 (14.4) P = 0.626 |

|

| Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | |||

| Pinedo 2012 | Wexner Faecal Incontinence Score reported before and after the treatment and reported as mean (SD) n = 24; Before: 16.6 (6‐20); After: 8.5 (0‐11) P = < 0.001 |

Wexner Faecal Incontinence Score reported before and after the treatmentand reported as mean (SD) n = 20; Before: 16.7 (5‐18); After: 13.1 (5‐17) P = 0.02 |

There was a significant difference in the final scores favouring the treatment group (P = 0.001) |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 4 Frequency of defecation (per day).

| Frequency of defecation (per day) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Hallgren 1994 # | N 28 mean 4.24 (SD 1.86) | N 28 mean 6.43 (SD 1.99) | |

| Read 1982 # | N 26 mean 1.6 (range 1‐6.3) | N 26 mean 2.4 (range 0‐7.7) | P < 0.001 Wilcoxon's rank sum test for paired data |

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 1.43 (SD 1) (loperamide oxide) | N 11 mean 2 (SD 1) | P < 0.02 |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | |||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 2.6 (SD 2.71) | N 15 mean 4.9 (SD 3.1) | |

| Sodium valproate versus placebo | |||

| Kusunoki 1990 # | N 17 mean 5.98 (SD 2.97) | N 17 mean 9.65 (SD 3.59) | |

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 6 Stool weight (grammes in 24 hours).

| Stool weight (grammes in 24 hours) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Read 1982 # | N 26 mean 102 (range 0‐467) | N 26 mean 186 (range 0‐466) | P < 0.001 Wilcoxon's rank sum test for paired data |

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 282 (SD 212) (loperamide oxide) | N 11 mean 423 (SD 163) | P = 0.11 |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | |||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 256 (SD 333) | N 15 mean 460 (SD 581) | |

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 16 Whole‐gut transit time.

| Whole‐gut transit time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 61 hours (SD 13) (loperamide oxide) | N 11 mean 39 hours (SD 15) | Significantly prolonged (P < 0.001) in patients taking loperamide oxide |

However, on active drug more people reported adverse effects, such as constipation, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, headache, and nausea in two trials: (Read 1982 #; Sun 1997 #) (Analysis 1.8). One trial reported that there were no adverse effects in either arm (Hallgren 1994 #) and adverse effects were not mentioned in another trial (Harford 1980 #).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 8 Number of people with adverse effects.

| Number of people with adverse effects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Read 1982 # | 18/26 (constipation 11, diarrhoea 4, nausea and vomiting 3, abdominal pain 2) | 1/26 (abdominal pain) |

| Sun 1997 # | 6/11 (headache, nausea, dizzyness, abdominal pain, constipation) (loperamide oxide) | 3/11 |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | ||

| Carapeti 2000a # | 3/36 (mild dermatitis after phenylephrine gel application, which settled when drug stopped) | 0/36 |

| Carapeti 2000b # | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| Cheetham 2001 # | 2/10 (burning sensation after phenylephrine gel application, which settled within minutes) | 0/10 |

| Park 2007 | Dermatitis reaction: 5/17; B = 1/12 Palpitation: 0/17; B = 1/12 Headache: 2/17; B = 0/12 | Dermatitis reaction: 1/12 Palpitation: 1/12 Headache: 0/12 |

| Sodium valproate versus placebo | ||

| Kusunoki 1990 # | 8/17 (abdominal pain and nausea) | 0/17 |

| Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | ||

| Pinedo 2012 | 0/24 | 0/20 |

Anorectal physiological measurements showed no clear differences between treatment periods (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.12; Analysis 1.14).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 12 Maximum anal squeeze pressure (mmHg).

| Maximum anal squeeze pressure (mmHg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Hallgren 1994 # | N 28 mean 223 (SD 82) | N 28 mean 219 (SD 93) |

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 163 (SD 86) (loperamide oxide) | N 11 mean 155 (SD 85) |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | ||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 94 (SD 68) | N 15 mean 96 (SD 68) |

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 14 Sensory threshold (cm water).

| Sensory threshold (cm water) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Hallgren 1994 # | N 28 mean 29.6 (SD 11.7) | N 28 mean 26.5 (SD 14.9) |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | ||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 12 (SD 12) | N 15 mean 31 (SD 62) |

B. Drugs enhancing anal sphincter tone versus placebo

Six trials were identified.

Phenylepinephrine gel

Five trials tested phenylepinephrine gel: in two trials the participants had passive faecal incontinence and structurally intact anal sphincters (Carapeti 2000a #; Cheetham 2001 #); Lumi 2009 enrolled participants who had undergone coloproctectomy with ileoanal anastomosis and J‐shaped ileal reservoir; Park 2007 enrolled participants with rectal cancer who had undergone lower resection; and Carapeti 2000b # recruited participants with an ileoanal pouch following colectomy for ulcerative colitis.

Overall, people were reported to be better when receiving the active drug rather than the placebo.

More people receiving phenylepinephrine gel rather than placebo achieved full continence in one trial: (Carapeti 2000b #) (Analysis 1.1) and

more people improved their incontinence symptoms in two trials: (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #) (Analysis 1.2).

Furthermore, high concentrations of active drug resulted in a higher maximum resting anal pressure in four trials: (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cheetham 2001 #; Park 2007) (Analysis 1.10.3 and Analysis 1.11). The complete results from the manometry are reported in Analysis 1.11.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 10 Maximum resting anal pressure (mmHg).

| Maximum resting anal pressure (mmHg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Loperamide versus placebo | ||

| Hallgren 1994 # | N 28 mean 62 (SD 16) | versus N 28 mean 55 (SD 9) |

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 76 (SD 40) (loperamide oxide ) | N 11 mean 69 (SD 35) |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | ||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 41 (SD 23) | N 15 mean 39 (SD 19) |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | ||

| Carapeti 2000a # | N 18 mean 65 (SD 21) | N 18 mean 54 (SD 21) |

| Carapeti 2000b # | N 12 mean 89 (SD 17) | N 12 mean 75 (SD 14) |

| Cheetham 2001 # | Statistically significant differences between phenylephrine gel (in concentrations of 30% and 40% only) | compared with placebo (P < 0.05) |

| Sodium valproate versus placebo | ||

| Kusunoki 1990 # | N 17 mean 63.6 (SD 12.4) | N 17 mean 42.5 (SD 8.9) |

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 11 Manometry.

| Manometry | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Domain | Drug (n = 17); reported as mean (SD) | Placebo (n = 12); reported as mean (SD) |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | |||

| Park 2007 | Resting pressure (mmHg) | Baseline: 30.0 (12.3); After: 27.3 (12.7) P = 0.362 | Baseline: 32.6 (14.2); After: 27.2 (15.0) P = 0.306 |

| Park 2007 | Squeezing pressure (mmHg) | Baseline: 143.3 (60.5); After: 160.4 (76.9) P = 0.083 | Baseline: 152.6 (86.5); After: 147.1 (76.5) P = 0.625 |

| Park 2007 | Sustained duration (s) | Baseline: 41.9 (24.5); After: 44.9 (48.3) P = 0.848 | Baseline: 39.6 (24.4); After: 32.8 (14.4) P = 0.187 |

| Park 2007 | Sphincter length (cm) | Baseline: 3.2 (0.9); After: 3.4 (0.8) P = 0.368 | Baseline: 3.5 (0.8); After: 3.4 (0.8) P = 0.743 |

| Park 2007 | High pressure zone (cm) | Baseline: 2.4 (2.1); After: 1.9 (0.5) P = 0.378 | Baseline: 2.1 (0.9); After: 2.3 (0.9) P = 0.556 |

Park 2007 used the Faecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) tool for reporting faecal incontinence: however, there did not appear to be any improvement from baseline in either of the arms, nor between the randomised arms (Analysis 1.5.2).

Adverse effects

However, more people complained of adverse reactions after application of phenylepinephrine gel such as localised dermatitis (Carapeti 2000a #; Park 2007) (Analysis 1.8) or a stinging or burning sensation which settled quickly (Cheetham 2001 #) (Analysis 1.8). Park 2007 reported 2/17 cases of headache in the phenylephrine group and none in the control group. Lumi 2009 reported a higher number of cases of faecal incontinence in the placebo group as shown in Analysis 1.3.2.

Sodium valproate

One trial tested sodium valproate in people with an ileoanal pouch due to either colectomy for ulcerative colitis or familial polyposis (Kusunoki 1990 #). More people receiving sodium valproate rather than placebo achieved full continence (Analysis 1.1), had fewer bowel actions per day (Analysis 1.4), and fewer perianal skin complications (Analysis 1.9) in one trial (Kusunoki 1990 #). They also had a higher maximal resting anal pressure compared with placebo (Kusunoki 1990 #) (Analysis 1.1.4).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 9 Number of people with perianal skin problems.

| Number of people with perianal skin problems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Sodium valproate versus placebo | ||

| Kusunoki 1990 # | 3/17 | 9/17 |

Adverse effects

More people complained of abdominal pain and nausea during sodium valproate administration (Kusunoki 1990 #);; (Analysis 1.8).

Zinc‐aluminium ointment

Pinedo 2012 conducted a trial comparing zinc‐aluminium ointment and placebo ointment. The ointments were applied on the anal canal mucosa three times daily over four weeks. Pinedo and colleagues used Wexner Faecal Incontinence Score before and after the treatment and reported a significant difference in the final scores favouring the treatment group (P = 0.001). They used the "Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score" tool for measuring quality of life. The quality of life score increased in both groups but more in the treatment group in all the parameters (Analysis 1.19.1).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 19 Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score.

| Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Domains | Drug (n = 17); reported as mean (SD) | Placebo (n = 12); reported as mean (SD) |

| Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | |||

| Pinedo 2012 | Lifestyle | Baseline: 2.49 (1.06); After: 3.58 (1.18) P = < 0.001 | Baseline: 2.50 (1.01); After: 2.55 (1.03) P = 0.151 |

| Pinedo 2012 | Conduct | Baseline: 2.19 (1.02); After: 3.12 (1.16) P = < 0.001 | Baseline: 2.17 (0.91); After: 2.37 (1.13) P = 0.104 |

| Pinedo 2012 | Embarrassment | Baseline: 1.54 (0.82); After: 2.5 (1.32) P = < 0.001 | Baseline: 1.56 (0.74); After: 1.76 (0.84) P = 0.043 |

| Pinedo 2012 | Depression | Baseline: 2.51 (1.01); After: 3.48 (1.17) P = 0.001 | Baseline: 2.46 (1.02); After: 2.71 (1.13) P = 0.093 |

| Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | |||

| Park 2007 | Lifestyle | Baseline: 2.9 (0.8); After: 2.9 (1.0) P = 0.801 | Baseline: 2.7 (0.5); After: 3.0 (0.8) P = 0.269 |

| Park 2007 | Coping | Baseline: 2.5 (0.9); After: 2.8 (0.9) P= 0.110 | Baseline: 2.5 (0.5); After: 2.8 (0.5) P = 0.119 |

| Park 2007 | Depression | Baseline: 3.2 (0.7); After: 3.2 (0.8) P = 0.415 | Baseline: 3.1 (0.5); After: 3.2 (0.5) P = 0.554 |

| Park 2007 | Embarrassment | Baseline: 2.7 (0.7); After: 3.0 (0.7) P = 0.090 | Baseline: 2.7 (0.6); After: 2.6 (0.8) P = 0.855 |

Adverse effects

In this trial no adverse effects or complications were reported.

C. Laxatives versus placebo

One trial comparing an osmotic laxative (lactulose) with no treatment showed that elderly people receiving lactulose required significantly less help from nurses for their bowel function, and soiled significantly fewer articles of clothing and linen (Ryan 1974) (Analysis 1.18).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 18 Help required from nurses.

| Help required from nurses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Laxative (lactulose) versus placebo | |||

| Ryan 1974 | 283 days of help | 322 days of help | P < 0.05 during trial period |

2. DRUG TREATMENT VERSUS ANY CONSERVATIVE TREATMENTS

No suitable trials were found.

3. DRUG TREATMENT VERSUS SURGICAL TREATMENT

No suitable trials were found.

4. DRUG TREATMENT IN COMBINATION WITH SURGICAL TREATMENT VERSUS SURGICAL TREATMENT ALONE

No suitable trials were found.

5. ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATION OF DRUGS

Four trials were identified, two in people with idiopathic diarrhoea (Chassagne 2000; Palmer 1980 #), one in adults with an ileoanal pouch (Cohen 2001 #) and one in obese adults using orlistat, which is a drug that blocks fat absorption from the gut but potentially has an adverse effect on the stools by increasing frequency, urgency and anal leakage due to reduced stool consistency (Fox 2005 #). The interventions were:

loperamide versus codeine versus diphenoxylate plus atropine (Palmer 1980 #);

a single osmotic laxative (lactulose) versus an osmotic agent along with a rectal stimulant and weekly enemas in patients with faecal incontinence and chronic rectal emptying impairments (Chassagne 2000);

oral versus rectal suppository administration of loperamide (Cohen 2001 #); and

three different doses of loperamide (Fox 2005 #).

Diphenoxylate, loperamide, codeine

Treatment with diphenoxylate was associated with a smaller percentage of solid stools, more faecal incontinence, more complaints of urgency, and more side effects compared to either loperamide or codeine but similar stool frequency (Palmer 1980 #) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATIONOF DRUGS, Outcome 1 Loperamide versus codeine versus diphenoxylate + atropine sulfate.

| Loperamide versus codeine versus diphenoxylate + atropine sulfate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Loperamide | Codeine | Diphenox. + atropine | Significance |

| Solid stool (%) | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | 67.8% (SD 34) | 58.4% (SD 25.9) | 36.3% (SD 33.3) | Diphenoxylate was associated with a signficantly smaller percentage of solid stools than either loperamide or codeine (P < 0.01) |

| Number of people with faecal incontinence | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | 2/25 | 3/25 | 6/25 | |

| Stool frequency | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | N 15 mean 1.8 (SD 0.3) | N 15 mean 1.9 (SD 0.3) | N 15 mean 1.9 (SD 0.3) | |

| Number of people with urgency | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | 3/16 | 4/17 | 9/17 | Diphenoxylate was significantly worse than loperamide or codenine, P < 0.05 (completed treatment periods only) |

| Adverse effects | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | 22 in 10/25 patients | 29 in 12/25 patients | 39 in 12/25 patients | Significantly more adverse effects with diphenoxylate than loperamide, P < 0.05 |

| Adverse effects causing withdrawal | ||||

| Palmer 1980 # | 4/25 | 4/25 | 5/25 | |

Lactulose, rectal stimulants, weekly enemas

In the study conducted by Chassagne and colleagues on patients aged 65 years or older in long‐term care units, the number of episodes of faecal incontinence and soiled laundry did not differ between people receiving lactulose and those receiving lactulose along with a rectal stimulant and weekly enemas (Chassagne 2000) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATIONOF DRUGS, Outcome 2 Osmotic laxative (lactulose) versus osmotic laxative + glycerine suppository + enema.

| Osmotic laxative (lactulose) versus osmotic laxative + glycerine suppository + enema | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Lactulose | Lactul + supp + enema | Significance |

| Number of faecal incontinence episodes in 4 weeks | |||

| Chassagne 2000 | N 61 mean 24 (SD 11.5 ) | N 62 mean 24 (SD 10.8) | P = 0.9 |

| Number of soiled items (bedding and or clothing) in 4 weeks | |||

| Chassagne 2000 | N 61 mean 80 (SD 16.1) | N 62 mean 78 (SD 20.7) | P = 0.55 |

Oral versus rectal administration of loperamide

Oral loperamide was better than rectal administration by suppository in reducing stool frequency (Cohen 2001 #) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATIONOF DRUGS, Outcome 3 Oral versus suppository administration of loperamide.

| Oral versus suppository administration of loperamide | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Data | Significance |

| Cohen 2001 # | Oral administration resulted in decreased stool frequency compared with suppository administration | P < 0.02 |

Diferent doses of loperamide

There was a trend for increasing stool firmness from the lowest to the highest dose of oral loperamide in the trial with obese patients using orlistat (Fox 2005 #) (Analysis 2.4), and a corresponding decrease in continence problems: there was almost no faecal incontinence on the two highest doses, 4 mg and 6 mg daily.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATIONOF DRUGS, Outcome 4 Different doses of oral loperamide.

| Different doses of oral loperamide | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome information | Significance |

| Stool frequency | ||

| Fox 2005 # | No effect | |

| Stool consistency | ||

| Fox 2005 # | Trend for increased stool consistency from median (IQR) score 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) with placebo to 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) with 6 mg dose (0 = all hard, 1 = all liquid) | |

| Faecal incontinence | ||

| Fox 2005 # | Less faecal spotting and incontinence with loperamide vs placebo | P < 0.05 |

| Dose response for faecal incontinence | ||

| Fox 2005 # | Significant positive dose‐response relationship with increasing dose of loperamide (reduced FI with 2 mg dose, and almost no FI with 4 mg and 6 mg doses) | |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Fox 2005 # | Adverse effects: none (specifically no severe constipation with the highest doses) | |

Discussion

The rationale behind the pharmacological management of faecal incontinence is that drugs may improve stool consistency or enhance anal sphincter function or promote complete rectal evacuation. The use of antidiarrhoeal and constipating agents in the treatment of faecal incontinence is a common clinical strategy, either alone or as an adjunct to other treatment modalities (surgery or conservative measures). Seven trials identified in this review assessed commonly used antidiarrhoeals (loperamide, codeine and diphenoxylate plus atropine) in people with chronic diarrhoea and those who had undergone ileoanal pouch surgery. Although these trials focused on the treatment of chronic diarrhoea, rather than on the management of faecal incontinence, they were included in this review because most of the participants presented with faecal incontinence as a complication of their underlying condition. Seven trials looked at novel pharmacological strategies to enhance anal sphincter function and two further trials tested ways of using lactulose for the treatment of faecal incontinence associated with impaired rectal emptying or constipation.

Summary of main results

Ten of the included trials assessed whether drug therapy may improve faecal incontinence related to liquid stool (either chronic diarrhoea or following ileoanal pouch surgery). Two trials evaluated elderly people with faecal incontinence associated with constipation or faecal impaction, and two further trials focused on people with passive faecal incontinence but structurally intact sphincters. One trial enrolled patients who were using a drug to treat their obesity (orlistat) to decrease the incidence of faecal incontinence. Only one of these 13 trials specifically evaluated the use of drugs in incontinent people with normal stool consistency but functionally impaired anal sphincters (Carapeti 2000a #). In one trial the diagnosis was not specified (Pinedo 2012). Findings of the included trials seem to indicate that anti‐diarrhoeal/constipating drugs may perform better than placebo in terms of continence outcomes and measures of bowel function (e.g. frequency, urgency, consistency, reduction in diarrhoea), although the participants may experience adverse effects. However, no statistical weight could be given to these findings.

One trial comparing three different anti‐diarrhoeal/constipating agents (loperamide, codeine, diphenoxylate plus atropine) in people with chronic diarrhoea showed that treatment with either loperamide or codeine was associated with a higher percentage of solid stools and fewer adverse effects and complaints of urgency than diphenoxylate plus atropine (Palmer 1980 #).

Five small trials (Carapeti 2000b #; Kusunoki 1990 #; Lumi 2009; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012) showed that people receiving drugs enhancing anal sphincter tone rather than placebo improved their symptoms. However, a further trial found no evidence of a statistically significant difference between phenylephrine gel and placebo (Carapeti 2000a #). The authors of this trial suggested that they might have used an inadequate dose of the active drug (phenylephrine gel), as their dose (10%) was determined by testing healthy volunteers. In another randomised cross‐over trial comparing different concentrations of phenylephrine gel in people with weak internal anal sphincters, doses of 30% and 40% increased the maximal anal canal resting pressure to the normal range, where doses of 10% and 20% had not done so (Cheetham 2001 #).

The drug most commonly used in clinical practice is still loperamide. Low‐dose loperamide (starting at 2 mg to 4 mg) titrated to the patient's symptoms is considered to be effective in patients with faecal incontinence and normal stool consistency. The greatest problem with loperamide is that it may be too potent, resulting in constipation and abdominal pain, particularly when the dose is increased rapidly (Palmer 1980 #; Read 1982 #). Liquid formulations are available if even lower doses are needed to minimise side effects.

Finally, it must be noted that physiological measurements of anal sphincter function are surrogate measures which correlate poorly with symptoms and severity of incontinence. Furthermore, due to the great variation in the technology and methods of assessing anorectal function in different units, these measures were not directly comparable across trials.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

No trials assessed the efficacy of drug treatment for people with anal sphincter trauma or assessed the use of drugs as an adjunct to other treatment modalities (surgery or conservative therapies).

Alternative measures to control faecal incontinence may be dietary (for example, see the excluded studies of fibre additives (Bliss 2001; Whitebird 2006)), or the use of complex management strategies for patients with constipation and bypass incontinence (Christensen 2006; Harari 2004). Cochrane reviews on these interventions are needed. There is a review on sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence (Mowatt 2007). There were no trials comparing these interventions directly with drugs.

Quality of the evidence

A quantitative meta‐analysis was not appropriate because the trials varied greatly in design, the characteristics and clinical diagnoses of participants, type of drugs used, duration of treatment, and choice of outcome measures. None of the 16 trials included a dose titration phase and only three trials considered different concentrations of the active drug (Cheetham 2001 #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #).

Eleven out of the 16 included trials were of cross‐over design with a short or no washout period between treatments. Only four of the cross‐over trials (Carapeti 2000a #; Carapeti 2000b #; Cohen 2001 #; Fox 2005 #) addressed the issue of duration of washout. No meaningful statistical analyses were possible in the cross‐over trials because results were either not provided at the end of the first trial period or not analysed using paired tests.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of this review broadly support the guidance provided by NICE for people with faecal incontinence (NICE 2007). After excluding specific causes of faecal incontinence, this clinical guideline recommends that loperamide should be used as first choice, starting at a low dose, and that codeine or diphenoxylate plus atropine (co‐phenotrope) should be offered to people who are unable to tolerate loperamide. However, this review found one small trial (Palmer 1980 #) that suggested that loperamide or codeine were preferable to diphenoxylate plus atropine.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is little evidence with which to assess the use of drug therapies for the management of faecal incontinence. The data available are consistent with the use of anti‐diarrhoeal/constipating drugs to improve the symptoms of people suffering from faecal incontinence due to liquid stools. They may cause side effects but these can be minimised by using low doses and titrating dose against effect. No data were found to support the use of anti‐diarrhoeal agents for the treatment of faecal incontinence in people with normal stool consistency. A novel approach, using drugs to enhance anal sphincter tone, may be effective in people with normal anal sphincter function, but again the evidence was limited. There was no evidence on the use of drug therapy for faecal incontinence compared with either conservative treatment or surgery.

Implications for research.

The current literature consists of small, short‐term trials that focus on the treatment of people with chronic diarrhoea, weak internal anal sphincters or difficulty with rectal evacuation (constipation). Larger more rigorous long‐term trials are needed to assess the effects of drug therapy for the treatment of people with faecal incontinence. The trialists should use the recommendations and principles set out in the CONSORT statement when designing and reporting their trials. In particular, well‐designed controlled trials of the use of drugs for the treatment of incontinent people with normal stool consistency are required.

We recommend that future trials of drug therapy for patients suffering from faecal incontinence should:

be of sufficient duration to assess long‐term effects of treatment;

include relevant primary outcome measures (e.g. number of people cured or improved) and not only surrogate outcomes;

analyse data using an intention‐to‐treat approach (with participants analysed in the groups to which they were allocated, whether or not they received that treatment);

outcome assessors blinded to treatment allocation;

if a cross‐over design is used, they should provide outcome data at the end of the first arm of treatment before cross‐over or, preferably, full information on the within‐individual comparison of treatments, and include an adequate washout period

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 May 2013 | New search has been performed | Three new trials have been added (Lumi 2009; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012). Risk of bias was re‐assessed on all the included trials in accordance with the current methodology. |

| 14 May 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Added three new trials Lumi 2009; Park 2007; Pinedo 2012. Risk of bias was re‐assessed on all the included trials in accordance with the current methodology. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 November 2008 | Amended | Moved dates to history |

| 5 May 2008 | New search has been performed | Minor update (Issue 3 2008), addition of two new trials, text and tables revised. Conclusions unchanged. |

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group in Aberdeen for their assistance with the review. The review authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the previous review authors Mark J Cheetham, Miriam Brazzelli, Christine Norton, Cathryn MA Glazener and Jean C Hay‐Smith. The review authors are grateful to Euan Fisher and Mayret Castillo for translation and data extraction of one trial (Lumi 2009).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people failing to achieve full continence | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.3 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.4 Sodium valproate versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2 Number of people failing to improve incontinence | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.3 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3 Number of faecal incontinence episodes | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.2 Phenylephrine cream versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Frequency of defecation (per day) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.3 Sodium valproate versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5 Faecal incontinence score | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5.2 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5.3 Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6 Stool weight (grammes in 24 hours) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7 Number of people using pads | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8 Number of people with adverse effects | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8.2 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8.3 Sodium valproate versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8.4 Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9 Number of people with perianal skin problems | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9.1 Sodium valproate versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10 Maximum resting anal pressure (mmHg) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10.3 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10.4 Sodium valproate versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 11 Manometry | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 11.1 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12 Maximum anal squeeze pressure (mmHg) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 13 Duration of squeeze (seconds) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 13.1 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14 Sensory threshold (cm water) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 15 Saline retention test (mL) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 15.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 15.2 Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 16 Whole‐gut transit time | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 16.1 Loperamide versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 17 Number of soiled items (bedding and or clothing) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 18 Help required from nurses | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 18.1 Laxative (lactulose) versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 19 Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 19.1 Zinc aluminium ointment versus placebo ointment | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 19.2 Phenylephrine gel versus placebo | Other data | No numeric data |

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 13 Duration of squeeze (seconds).

| Duration of squeeze (seconds) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | ||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 87 (SD 127) | N 15 mean 86 (SD 127) |

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 15 Saline retention test (mL).

| Saline retention test (mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Loperamide versus placebo | |||

| Sun 1997 # | N 11 mean 223 (SD 274) (loperamide oxide) | versus N 11 mean 150 (SD 208 ) | P = 0.07 |

| Diphenoxylate + atropine versus placebo | |||

| Harford 1980 # | N 15 mean 492 (SD 461) | N 15 mean 486 (SD 364) | |

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 DRUG VERSUS PLACEBO, Outcome 17 Number of soiled items (bedding and or clothing).

| Number of soiled items (bedding and or clothing) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Drug | Placebo | Significance |

| Ryan 1974 | 154 items during trial period | 332 items | P < 0.01 |

Comparison 2. ONE DRUG VERSUS ANOTHER DRUG OR A COMBINATIONOF DRUGS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Loperamide versus codeine versus diphenoxylate + atropine sulfate | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.1 Solid stool (%) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.2 Number of people with faecal incontinence | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.3 Stool frequency | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.4 Number of people with urgency | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.5 Adverse effects | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.6 Adverse effects causing withdrawal | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2 Osmotic laxative (lactulose) versus osmotic laxative + glycerine suppository + enema | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.1 Number of faecal incontinence episodes in 4 weeks | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.2 Number of soiled items (bedding and or clothing) in 4 weeks | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3 Oral versus suppository administration of loperamide | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Different doses of oral loperamide | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.1 Stool frequency | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.2 Stool consistency | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.3 Faecal incontinence | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.4 Dose response for faecal incontinence | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.5 Adverse effects | Other data | No numeric data |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Carapeti 2000a #.

| Methods | Cross‐over randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 36 adults (22 women) with passive FI and structurally intact anal sphincters Mean age 58 years (range 28 to 81) Mean duration of faecal incontinence: 5 years (SD 4) Characteristics of patients were comparable at baseline Exclusion criteria: disruption of anal sphincter muscle on endoanal ultrasound examination, concomitant use of tricyclic or mono‐amine oxidase inhibitors, hypertension, aortic aneurysm or ischaemic heart disease, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease and surgically repairable sphincter damage. | |

| Interventions | A: 10% phenylephrine gel B: placebo gel (0.5 mL), both used anally twice a day Length of treatment: 4 weeks (two four‐week treatment periods with a one‐week washout period) Dose titration: the choice of 10% phenylephrine gel was based on previous pilot studies on healthy volunteers | |

| Outcomes | Subjective cure: A: 0/36, B: 0/36 Subjective improvement in symptoms: A: 6/36, B: 2/36 [A: 28% versus B: 9% at the end of the first trial period] Incontinence score (n, mean, SD): A: 18, 12.5 (3.4), B: 18, 12.6 (4.2) (no difference) Adverse effects: A: 3/36, B: 0/36 (localised mild dermatitis, settled when drug stopped) Maximum anal resting pressure (n, mean, SD): A: 18, 65 (21), B: 18, 54 (21) (no difference) Anodermal blood flow (no change) | |

| Notes | 15 patients continued with loperamide during the study Sample size calculation pre‐stated (16 patients required) Suggestion of an interaction between treatment and placebo periods, possibly reflecting an insufficient washout period | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation was carried out by a pharmacist by means of computer generated random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The randomization code was kept in the hospital pharmacy and made known to the investigators only after analysis of the completed study." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Repored as "double‐blind" trial but it is not specified who was blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Repored as "double‐blind" trial but it is not specified who was blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No incomplete data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not available |

| Was use of a cross over design appropriate? | Low risk | Yes |

| Is it clear that the order of receiving treatment was randomised? | Low risk | Used computer‐generated random numbers. |

| Can it be assumed that the trial was not biased from carry over effects? | Unclear risk | "4 weeks treatment periods separated by a 1 week washout period" |

Carapeti 2000b #.

| Methods | Cross‐over randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 12 adults (7 women) with FI after ileoanal pouch surgery for ulcerative colitis Median age 44 years (range 29 to 67) 8 had nocturnal incontinence only, 4 had both diurnal and nocturnal incontinence Exclusion criteria: active pouchitis, disruption of anal sphincter muscles on endoanal ultrasound examination, concomitant use of tricyclic or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease or aortic aneurysm. | |

| Interventions | A: 10% phenylephrine gel B: placebo gel (0.5 mL), both used anally twice a day Length of treatment: 4 weeks (two four‐week treatment periods with a one‐week washout period) Dose titration: the choice of 10% phenylephrine gel was based on previous pilot studies on healthy volunteers | |

| Outcomes | Cure: A: 4/12, B: 0/12 Subjective improvement in symptoms: A: 6/12, B: 1/12 Incontinence score (28 day symptom score, n, mean, SD): A: 12, 12.2 (5.7), B: 12, 16.5 (4.4) Adverse effects: A: 0/12, B: 0/12 Maximum anal resting pressure (n, mean, SD): A: 12, 89 (17), B: 12, 75 (14) Anodermal blood flow (no difference) | |

| Notes | 8 patients continued with loperamide during the study Suggestion of an interaction between treatment and placebo periods, possibly reflecting an insufficient washout period | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Random assignment was performed using random numbers generated by a scientific calculator, and the randomization code was kept in the hospital pharmacy and made known to the investigators only after analysis of the completed study" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Random assignment was performed using random numbers generated by a scientific calculator, and the randomization code was kept in the hospital pharmacy and made known to the investigators only after analysis of the completed study" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Repored as "double‐blind" trial but it is not specified who was blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Repored as "double‐blind" trial but it is not specified who was blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No incomplete data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not available |

| Was use of a cross over design appropriate? | Low risk | Yes |