Abstract

Objective:

To characterize barriers to and facilitators of successful iron therapy in young children with IDA from an in-depth parental perspective.

Study design:

Prospective, mixed-methods study of children age 9 months to 4 years with a diagnosis of nutritional IDA by clinical history and laboratory criteria and their parents. Clinical data were obtained from the electronic health record. Semi-structured interviews focused on knowledge of IDA, clinical effects, experience with iron therapies, and motivation were conducted with the parent who identified as the child’s primary caregiver.

Results:

Twenty patient-parent dyads completed the study; 80% (n=16) identified as Hispanic/Latino (white). Patients’ median age was 23 months (50% male); median initial hemoglobin concentration was 8.2 g/dL and duration of oral iron therapy was 3 months. Parents’ median age was 29 years (85% female); 8 interviews (40%) were conducted in Spanish. Barriers included difficulty in administering oral iron due to side effects and poor taste. Facilitators included provision of specific instructions, support from health care providers and additional caregivers at home, motivation to benefit child’s health, which was strengthened by strong emotional reactions (ie, stress, anxiety) to therapy and follow-up, and an appreciation of child’s improvement with successful therapy completion.

Conclusions:

Our findings support the need for interventions designed to promote oral iron adherence in children with IDA. Rather than focusing on knowledge content related to IDA, interventions should aim to increase parental motivation by emphasizing health benefits of adhering to iron therapy and avoidance of more invasive interventions.

Keywords: qualitative study, adherence, self-determination theory of motivation, transfusion, intravenous iron

Iron deficiency due to excessive cow milk intake and low-iron diet affects approximately 15% of children age 1 to 2 years of age; approximately 3% have frank iron deficiency anemia (IDA).(1) Children of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, from low-income and/or primarily Spanish-speaking homes are disproportionately affected.(2–4) Critically, IDA often occurs at a period of rapid neurodevelopment(5, 6) and is associated with inferior neurocognitive outcomes, poorer executive functioning, and decreased visual and auditory processing time.(7–9) Oral iron therapy mitigates the consequences of IDA,(10) and most patients who successfully adhere to therapy have a full recovery within a typical 3 to 6 month treatment course. However, rates of non-adherence are high due to its unpleasant effects and bad taste.(11) Given that more severe and chronic IDA is associated with worse outcomes, such high rates of incomplete therapy may prolong the extent and severity of its negative consequences.

In-depth studies examining barriers to oral iron therapy adherence in young children are lacking. Even fewer studies exist to assess facilitators of its adherence. Qualitative research is a vehicle that can ascertain important information from relevant stakeholders.(12) Information derived from the parental perspective can be utilized to develop interventions that more effectively address elements of care that are important for patients and thereby increase treatment success.(13) The objective of this study was to characterize barriers to and facilitators of iron therapy in young children with nutritional IDA from their parents’ (i.e. primary caregiver’s) perspective.

METHODS

This was a prospective, mixed-methods study conducted in the outpatient hematology clinic of the Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, Texas, a large, freestanding tertiary care children’s hospital. Quantitative clinical data were abstracted from the electronic health record on children with nutritional IDA and qualitative data obtained via semi-structured interviews with parents who identified as their child’s primary caregiver at home.(14) Individual in-depth interviews were conducted, and themes representing the parental experience were identified.(12) All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine (Protocol H-40112).

Participants and Recruitment

Potential patients were identified by screening the outpatient hematology clinic schedule. Children age 9 months to 4 years with nutritional IDA, defined as a history of excessive cow milk intake (>24 ounces per day) or exclusive breast milk without iron supplementation, and laboratory indices: hemoglobin concentration (Hgb) ≤10 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) ≤70 fl, serum ferritin ≤15 ng/mL or total iron binding capacity ≥425 mg/dL,(10, 15) were identified for recruitment. Children with other causes of anemia, IDA due to an underlying gastrointestinal disorder, chronic inflammatory conditions, history of prematurity (less than 30 weeks gestational age), or who were unable to tolerate oral medications were excluded. Patient-parent pairs were eligible for enrollment if the parent who identified as the child’s primary caregiver spoke English or Spanish. Purposive sampling was utilized to recruit parents from both language preference groups to ensure adequate representation of each group. Patients could have received iron therapy for up to 12 months duration at the time of enrollment. Parents were approached for enrollment during their child’s regularly scheduled clinic visit, and written informed consent was obtained prior to study participation.

Data Collection

After explaining the study objective (i.e., to better understand the parent’s perspective on iron therapy), a research coordinator trained in qualitative methods interviewed each parent in-person in association with a scheduled clinic visit in a private examination room. Interviews with primarily Spanish-speaking parents were conducted with an in-person professional Spanish interpreter. All interviews were audio-recorded.

Interview Guide

Each interview followed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions; probes were used to clarify, understand, and/or expand responses as appropriate. The guide was developed with a multidisciplinary team consisting of three pediatric hematology-oncology subspecialists, one academic general pediatrician with expertise in health disparities, and a behavioral science researcher with expertise in nutrition and qualitative research methods, and informed by the self-determination theory of motivation (SDT).(16) The SDT proposes that behavior is motivated by three basic psychological needs: autonomy (i.e. the belief that the individual has a choice and control), competence (i.e. the belief that one has the knowledge, skill, and ability to successfully perform a particular behavior), and relatedness (i.e. sense of connection with self and important others, such as a family member, in regards to a particular behavior). Satisfaction of these needs enhances intrinsic (i.e., self-directed) motivation to perform the behavior. The SDT was selected as the theoretical framework for this study based on the hypothesis that motivation would be an important component of the parents’ likelihood of adhering to their child’s prescribed oral iron therapy.(16) Interview questions are shown in Table I. At the end of each interview, parents completed a demographic survey.

Table I.

Interview Questions for Parents of Children with IDA

| Diagnosis of IDA |

| 1. Let’s begin by talking about the definition of iron deficiency anemia. How would you describe iron deficiency anemia to a friend or family member? |

| Consequences of IDA |

| 2. How does iron deficiency anemia affect your child’s health (either in a good or bad way)? If the anemia was not found, what do you think would have happened? |

| Oral iron medicine / Treatment regimen |

| 3. Tell me about the iron treatment that your child received. In your opinion, why was your child given an iron medicine? |

| Adherence to oral iron / Motivation |

| 4. What was it like to give the iron medicine to your child? What, if anything, made it hard to give the medicine to your child? What, if anything, made it easier to give the medicine to your child? |

| 5. What were your reasons for giving your child the iron medicine? |

| 6. What are the biggest problems in giving iron medicine for several months? |

| 7. What would help parents take care of a child with iron deficiency anemia? |

| 8. In your opinion, what could be done to motivate parents to complete iron deficiency anemia treatment? |

| Alternate treatment options |

| 9. Did your provider discuss with you other ways to treat iron deficiency anemia? If so, what were they? |

| 10. [Brief overview of intravenous iron therapy provided.] Tell me your thoughts about this type of treatment option [intravenous iron therapy]. |

| Summarizing question |

| 11. What is the best way for you to receive information about iron deficiency anemia and its treatment options? |

Interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim in the original language spoken; all identifiers were removed to protect confidentiality. Spanish language transcripts were then professionally translated into English. Analysis was conducted on the English language transcripts and were reviewed for accuracy by the PI, who read each transcript while listening to the corresponding audio recording and made corrections, if indicated. After 20 interviews, the research team determined that theoretical saturation was achieved, as evidenced by the lack of emergence of new information, and enrollment was closed. All interviews were conducted from February 2017 through January 2018.

Data collection from the electronic medical record included primary provider referral information, dietary history, oral iron therapy (including dosing and duration), receipt of intravenous iron and/or red blood cell transfusion, hematologic, and iron laboratory measures, as well as duration of hematology follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

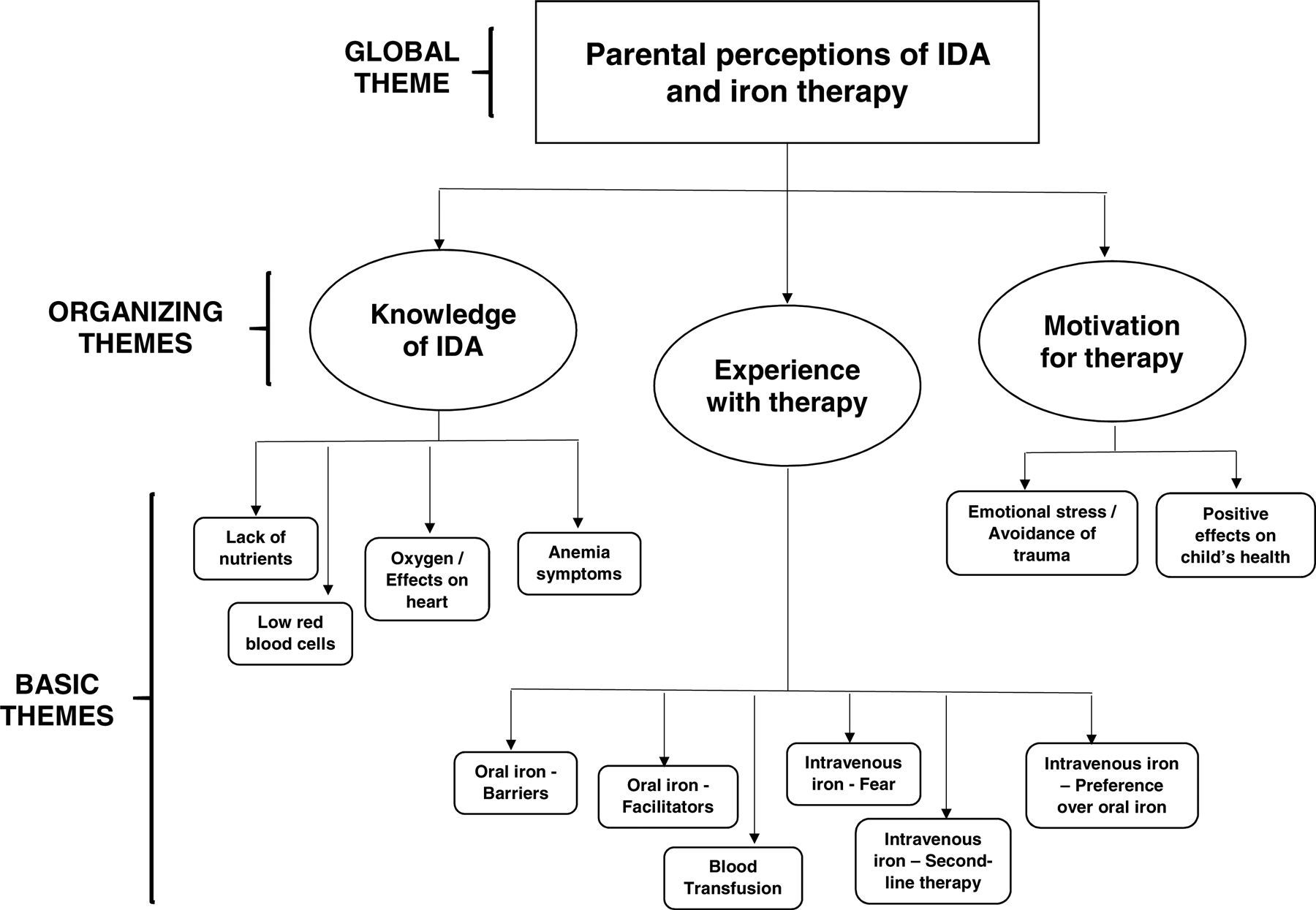

A hybrid thematic analysis approach was used.(17) Utilizing a preliminary codebook designed with a priori codes, 2 trained members of the research team reviewed transcripts multiple times to develop familiarity with responses.(12, 16) A priori codes were then applied. Emergent codes (i.e. concepts that were identified or evolved from data review) were generated to help ensure the participants’ voices were captured. After analysis, members reviewed codes together, and through discussion, codes were grouped into basic themes followed by higher order themes to create a thematic network (Figure). Themes that emerged from parent interviews were utilized to better understand IDA and iron therapies from the parental perspective.

FIGURE.

Thematic Network of Parents’ Perceptions of IDA and Iron Therapy

RESULTS

Twenty patient-parent dyads completed the study (Table II). Patients’ median age was 23 months (range 12 to 40); 50% (n=10) were male. Parents’ median age was 29 years (range 29 to 41); the majority (85%, n=17) were female; 80% (n=16) of families identified as Hispanic/Latino (White). Eight interviews (40%) were conducted in Spanish. Patients’ median initial Hgb was 8.2 g/dL (range 4 to 9.5). Patients’ median final available Hgb was 11.3 g/dL (range 7.2 to 13.1). During their hematology treatment course, the majority of patients (n=13, 65%) were treated with ferrous sulfate and a smaller portion (n=6, 30%) received iron polysaccharide complex (Table II). The most common oral iron treatment regimen included elemental iron dosing of 3 mg/kg/day (range 1 to 6 mg/kg/day) administered once daily (70%). Median duration of oral iron therapy of enrolled subjects was 3 months. Two patients (10%) had received intravenous iron therapy; another 2 (10%) had received red blood cell transfusion for severe anemia.

Table II.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of IDA Patients and Their Parents

| Patient-Parent Dyads, N=20 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity (self-identified), n (%) | ||

| White, Hispanic/Latino | 16 | (80%) |

| Asian | 3 | (15%) |

| Black or African American | 1 | (5%) |

| Patients, N=20 | ||

| Age at interview, median (range), months | 23 | (12 to 40) |

| Female Sex, n (%) | 10 | (50%) |

| Initial hemoglobin concentration, median (range), g/dL | 8.2 | (4 to 9.5) |

| Final hemoglobin concentration, median (range), g/dL | 11.3 | (7.2 to 13.1) |

| Therapy | ||

| Receipt of packed red blood cell transfusion, n (%) | 2 | (10%) |

| Oral iron therapy, n (%) | ||

| Ferrous sulfate | 13 | (65%) |

| Iron polysaccharide complex | 6 | (30%) |

| Poly-vi-sol with iron | 1 | (5%) |

| Oral iron therapy duration, median (range), months | 3 | (1 to 12) |

| Received intravenous iron therapy (second-line), n (%) | 2 | (10%) |

| Parents, N=20 | ||

| Age at interview, median (range), years | 29 | (20 to 41) |

| Female Sex, n (%) | 17 | (85%) |

| Primarily Spanish-speaking, n (%) | 8 | (40%) |

| Educational attainment (n=19), n (%) | ||

| Less than high school | 6 | (32%) |

| High school / Graduate Equivalent Degree (GED) | 5 | (26%) |

| Some college | 6 | (32%) |

| Bachelor degree | 2 | (11%) |

| Annual household income, median bracket | 35 to 50K | |

| Total children in home, median (range) | 2 | (1 to 5) |

| Number of caregivers in home, median (range) | 2 | (1 to 4) |

Themes

Under the global theme of parents’ perceptions of IDA and iron therapy, 3 organizing themes emerged: knowledge of IDA, experience with iron therapy, and motivation to adhere to therapy (Figure). Each organizing theme had 2 to 6 basic themes, discussed separately below. Given that the majority of enrolled subjects identified as Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, an extensive analysis based on ethnicity was not performed.

Review of interview transcripts with the four non-Hispanic/Latino parent participants found no significant differences in themes from that subset compared with the participants as a whole. No significant differences were identified between the English-speaking and Spanish-speaking participants. Quotes supporting themes are presented in Table III; for clarity, several key quotes are embedded in the text.

Table III.

Themes and Quotes from Parents of Children with IDA

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| IDA Knowledge | |

| Lack of nutrients / Low red blood cells |

|

| |

| |

| Oxygen / Effects on heart |

|

| Anemia symptoms |

|

| |

| |

| Experience of iron therapy | |

| Blood transfusion |

|

| |

| Oral iron - barriers |

|

| |

| |

| Oral iron – facilitators |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Intravenous iron - preference for oral iron |

|

| Intravenous iron - fear |

|

| |

| Intravenous iron - second-line therapy |

|

. | |

| Intravenous iron - preference over oral iron |

|

| |

| Motivation for therapy | |

| Emotional stress / Avoidance of trauma |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Positive effects on child’s health |

|

| |

| |

| |

Knowledge of IDA

Parents expressed a basic understanding of the cause of IDA, described as a lack of nutrients, and its clinical consequences of low red blood cells and symptoms of anemia (Table III).

Lack of nutrients

Many parents regretted not being better informed about preventive dietary measures. Specifically, they did not realize how critical iron was to their child’s health and the impact of dietary choices on overall iron intake. Several parents admitted that although their children were “picky eaters,” they thought that cow’s milk provided adequate nutrition and did not realize that excessive intake could result in anemia.

Low red blood cells, Oxygen / Effects on heart, Anemia symptoms

Parents were consistently able to define IDA but gave variable responses to its clinical effects on their child, ranging from oxygen delivery and cardiac effects to skin pallor and energy. Some misinformation was also present, including concern that untreated anemia could progress to leukemia. Although deeper understanding was often absent, most understood that IDA affects multiple parts of the body, and in retrospect, 13 parents (65%) were able to recall anemia symptoms their children had been displaying prior to initiation of iron therapy such as poor concentration, pallor, and increased sleepiness. “Yea, well he really didn’t experience much other than the paleness and not having enough color. He looked really yellow. But energy, now that I see it, his energy was kind of low” (Parent 4).

Experience with iron therapy

Several important aspects of therapy, including impact of blood transfusion, and perception of and experienced benefits from either oral or intravenous iron therapy, were mentioned (Table III).

Blood transfusion

Parents reported anxiety with regard to their child’s actual or potential need for a blood transfusion, due to the child’s young age.

Oral iron – Barriers

Parents had contrasting views on oral iron. Negative features including poor taste and resultant difficulty in administering it to their child, were identified as barriers. In retrospect, some parents noted that giving either intravenous iron or a transfusion would have allowed them to avoid constant “battles” with their child over oral iron therapy.

Oral iron - Facilitators

Specific administration instructions, direct encouragement from health care providers (i.e. physicians, nurses), and caregiver support in the home, were all facilitators of oral iron therapy. One parent (5) stated that her child’s doctor “…informed me on things to do. Don’t give it between meals, follow it with orange juice, and don’t give her milk after it…So, I felt like that was very helpful.” Setting an alarm, having patience with the duration of therapy required, and transition to better tasting formulations were also mentioned as facilitators in a subset of parents.

Intravenous iron – Preference for oral iron, Fears

Several parents expressed preference for oral iron therapy when provided a description of the alternative of intravenous iron. Others explicitly expressed fear of their child receiving more “intensive” intravenous iron therapy as well as sadness of their having “failed” oral iron therapy.

Intravenous iron – Second-line therapy, Preference over oral iron

Despite its associated fears, most parents demonstrated willingness for intravenous iron, if necessary. Regarding when to transition from oral to intravenous iron, decision-making was deferred to their medical provider. Two parents whose children received both oral and intravenous iron both reported that they wished their child had been treated more aggressively upfront to minimize the time it took for him to get well.

Motivation for therapy

Parental motivation fell into two broad categories: emotional stress for both parent and child, and the child’s physical health (Table III).

Emotional stress / Avoidance of trauma

Parents frequently expressed the desire to minimize their child’s negative or “traumatic” experiences related to both therapy and ongoing follow-up care. One mother reported that her partner (e.g. patient’s father) stopped attending medical visits because he was so upset at seeing his child have blood drawn. When asked what they would tell to other parents of children with IDA, parents provided encouragement while also acknowledging the difficulties associated with care. “Just explain to parents…it could go real bad if you don’t supplement your baby with iron. It could be dangerous because their anemia could get worse, and we don’t wanna be going through all this” (Parent 3).

Positive effects of iron therapy on child’s health

Several parents explicitly stated they were motivated to get their child’s iron levels up because they knew it would help him/her. “I wanted him to get well. I wanted him to have it. I was pushing for him to have the medication. I know that it’ll help him” (Parent 11). Fourteen parents (70%) noted positive effects in their child’s health including improved skin color, increased energy, and less pica. Prevention of more severe disease, as well as experiencing relief after recovery, was also motivating for parents.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the experience of oral iron therapy in young children with IDA, as well as factors that affect motivation to adhere, from an in-depth parental perspective. Understanding this information may contribute to the development of effective approaches to facilitate adherence and enhance treatment outcomes. Our cohort included young children with moderate to severe IDA from both primarily English-and primarily Spanish-speaking homes who received a range of iron therapies. Interviews with parents revealed challenges with the treatment regimen and child resistance as barriers to adherence. Facilitators of oral iron adherence included the provision of specific information on the treatment regimen, support from health care providers and additional caregivers within the home, desire to minimize their child’s “traumatic” experiences, strong emotional reactions to different aspects of therapy, and motivation to see their child improve.

Previous research has found that non-adherence in children with both acute and chronic medical conditions is a significant problem, with rates estimated at 30 to 50%.(18) Qualitative research has demonstrated that beliefs about the primary condition and/or treatment, challenges with the treatment regimen, and child resistance to medication all impact adherence.(19, 20) A study of 195 children with IDA found that one-third were non-adherent to treatment due to factors such as child refusal/spit-up, gastrointestinal upset, staining of teeth, and parental discretion.(11) In our study, parents’ lack of knowledge regarding IDA and its negative clinical consequences was not a reported barrier to oral iron treatment. Known negative side effects of oral iron therapy, such as poor taste, were confirmed to make its administration difficult for some.(11)

This study is consistent with previous research in which strong emotional reactions to illness management impact adherence.(21, 22) Emphasis on the value of the treatment, the effect of adherence on treatment outcomes, elicitation of patients’ feelings, and help from family members, are all strategies that have been shown to improve adherence to a medication regimen.(22) Parents in our cohort reported both stress and anxiety related to onset of diagnosis and traumatic experiences, sadness with failure of oral iron therapy, as well as happiness and relief upon their child’s improvement. They reported that positive health outcomes in their child, and help from other caregivers in the home (i.e. grandparent, older sibling), were important in facilitating adherence.

Our findings have important potential implications for clinicians who seek to improve adherence in their affected patients. Most significantly, focusing on drivers of motivation, rather than education on IDA, may help facilitate adherence to a greater extent. For young children with nutritional IDA, this specifically means that health care providers should emphasize health benefits of iron therapy for the child and the ability to minimize future emotional burden and stress with successful iron administration. Within the context of the SDT, acknowledging that parents have a choice in therapy decisions (autonomy), that they have the ability to successfully give iron therapy (competence), especially when provided specific instructions and additional support, and highlighting their sense of parent-child connection (relatedness), therapy adherence should improve. Notably, a smaller subset of parents reported having wished to receive intravenous iron earlier in the treatment course. In the future, it may be important to consider such alternative treatment approaches for families based on their individual values and preferences.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a specialty clinic at a tertiary care center. Patients present with more severe IDA initially and may be less reflective of the general population with milder IDA. However, we believe that by characterizing this high-risk population, we have learned important information about patient/parent characteristics and parental understanding of IDA and motivation, which will apply broadly to other affected patients. Second, no objective measures of adherence were assessed to determine if there were differences in themes amongst families based on adherence levels. Third, the majority of our population identified as Hispanic/Latino. Though Hispanic/Latino children are disproportionately affected by this condition, this is likely also reflective of our center’s urban setting in a city with a high Hispanic/Latino population, and the large number of patients from low socioeconomic status backgrounds it serves.(2) Children from all racial and ethnic groups are affected by IDA, and we performed continuous review of our qualitative data and enrolled parents until no new information or themes emerged to maximize our ability to communicate the parents’ voice. Enrolling Hispanic/Latino parents from both primarily English-speaking and primarily-Spanish speaking homes also allowed us to ensure that future intervention message content adapted for both English and Spanish-speaking families would have formative data to support it. Finally, Spanish-speaking families were not specifically asked about the provision of instructions in Spanish, nor was health literacy formally assessed. These two aspects would be important to address in future related studies.

Parents of children with IDA experience barriers to adherence common to other conditions. Facilitators of oral iron adherence was reflective of both common motivating factors as well as specific and novel considerations for this young patient population. Data from this study will inform the message content for a behavioral intervention aimed to improved adherence to oral iron therapy in parents of young children with nutritional IDA. High risk groups, in particular, such as Hispanic/Latino patients from both primarily English-and Spanish-speaking homes, and those of low socioeconomic status, would stand to benefit most. Adherence interventions should aim to address parental motivation by emphasizing that adherence to oral therapy improves health outcomes and avoids the stress and anxiety related to more prolonged or invasive treatments.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH (K23HL132001) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- IDA

iron deficiency anemia

- SDT

self-determination theory of motivation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented at the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 31st Annual Meeting, << >>,2019, << >>.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta PM, Perrine CG, Mei Z, Scanlon KS. Iron, Anemia, and Iron Deficiency Anemia among Young Children in the United States. Nutrients. 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brotanek JM, Gosz J, Weitzman M, Flores G. Iron deficiency in early childhood in the United States: risk factors and racial/ethnic disparities. Pediatrics. 2007;120:568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotanek JM, Halterman JS, Auinger P, Flores G, Weitzman M. Iron deficiency, prolonged bottle-feeding, and racial/ethnic disparities in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1038–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotanek JM, Schroer D, Valentyn L, Tomany-Korman S, Flores G. Reasons for prolonged bottle-feeding and iron deficiency among Mexican-American toddlers: an ethnographic study. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta PM, Hamner HC, Suchdev PS, Flores-Ayala R, Mei Z. Iron status of toddlers, nonpregnant females, and pregnant females in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:1640S–6S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker RD, Greer FR, Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126:1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lozoff B, Brittenham GM, Wolf AW, McClish DK, Kuhnert PM, Jimenez E, et al. Iron deficiency anemia and iron therapy effects on infant developmental test performance. Pediatrics. 1987;79:981–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, Mollen E, Wolf AW. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Algarin C, Peirano P, Garrido M, Pizarro F, Lozoff B. Iron deficiency anemia in infancy: long-lasting effects on auditory and visual system functioning. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers JM, Buchanan GR. Disorders of iron metabolism: New diagnostic and treatment approaches to iron deficiency. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(3):393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers JM, Daniel CL, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Deficiencies in the management of iron deficiency anemia during childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:743–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed: Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steptoe A, Freedland KE. Handbook of behavioral medicine: methods and applications. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W, Creswell J. The use of “mixing” procedure of mixed methods in health services research. Medical care. 2013;51:e51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers JM, Buchanan GR. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North America. 2014;28:729–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Intl J Qual. 2006;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finney JW, Hook RJ, Friman PC, Rapoff MA, Christophersen ER. The overestimation of adherence to pediatric medical regimens. J Assoc Care Child Health. 1993;22:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santer M, Ring N, Yardley L, Geraghty AW, Wyke S. Treatment non-adherence in pediatric long-term medical conditions: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies of caregivers’ views. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, Ersser SJ, Lewis-Jones S, Muller I, et al. Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drotar D Strategies of adherence promotion in the management of pediatric chronic conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:716–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]