In December 2019, patients with novel corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China [1]. The pathogen analysis discovered a new type of coronavirus from infected airway epithelial cells [2], which was named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3]. At a time when Chinese people were heading home to celebrate the Spring Festival, many latent cases left Wuhan, which led to the emergence of imported COVID-19 cases across the mainland of China and into some other countries [4, 5]. Shanghai is one of the major cities with imported cases [4, 5].

Short abstract

COVID-19 emerged in Wuhan, China, and threatens public health. The clinical and CT features of early stage patients have not previously been characterised. This study aimed to explore the early stage clinical and CT signs. http://bit.ly/38Tbq08

To the Editor:

In December 2019, patients with novel corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China [1]. The pathogen analysis discovered a new type of coronavirus from infected airway epithelial cells [2], which was named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3]. At a time when Chinese people were heading home to celebrate the Spring Festival, many latent cases left Wuhan, which led to the emergence of imported COVID-19 cases across the mainland of China and into some other countries [4, 5]. Shanghai is one of the major cities with imported cases [4, 5].

COVID-19 is mainly diagnosed using real-time PCR to detect SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid [4]. Due to the limited supply of real-time PCR kits and the emergence of false-negative nucleic acid cases, some experts have proposed the use of time-saving chest computed tomography (CT) to diagnose suspected cases rather than real-time PCR [6]. CT features at the early stage of COVID-19 have not particularly been studied yet, which is vital to the early identification of suspected cases. The purpose of this study was to explore the early stage clinical and CT features of nucleic acid-positive COVID-19.

From 20th to 30th January 2020, 44 COVID-19 patients (male:female ratio 25:19; median age 48.5 years; age range 20–76 years) at our institution who met the entry criteria (patient interval time between symptom onset and CT scan was <4 days [7]) were enrolled in this study. Their clinical data included the onset of symptoms and the main laboratory findings, and they were divided into three groups: A decreased; B normal; C elevated. Observation parameters on CT included: lesion distribution; size (maximum diameter on axial images); attenuation category (type I pure ground-glass opacities (pGGOs); type II GGOs with consolidation; type III GGOs with interlobular septal thickening; type IV consolidation); lesion-related signs (vessel expansion, air bronchogram); mediastinal lymphadenectasis (>1 cm in short-axis diameter); and pleural effusion. CT score was defined to quantify the pulmonary lesions in CT. The design formula was: size (cm) × attenuation category weight. The attenuation category weight was 1 for type I, 2 for type II/III and 3 for type IV, which was discussed by two experienced chest radiologists, especially for the infectious disease diagnosis.

Amongst the 44 patients, the onset symptoms were mainly fever (95.45%), followed by fatigue (15.91%), dry cough (13.64%), anorexia (13.64%), expectoration (11.36%), etc. 52.27% of patients had a decreased lymphocyte count, while 50% had a decreased CD3+ T-cell count, 43.18% had a decreased CD4+ T-cell count and 45.45% had a decreased CD8+ T-cell count. All patients presented with an elevated level of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, while 75% had elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and 29.55% had elevated procalcitonin. 19 (43.18%) patients had an elevated lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) level, while 15.91% had elevated alanine aminotransferase and glutamyltransferase, and 13.64% had elevated aspartate aminotransferase. In many patients, levels of total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), prealbumin (PAB), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) were decreased (40.91%, 81.82%, 50%, 61.37% and 52.27%, respectively).

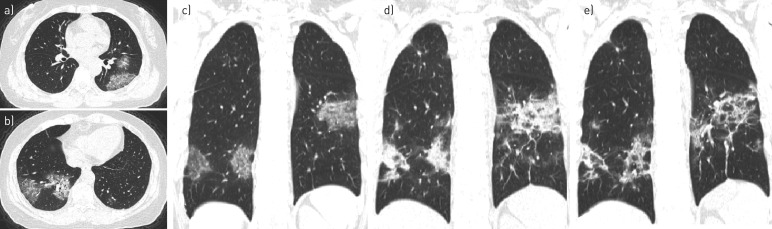

A total of 456 pulmonary lesions were detected via CT in 44 patients. Of them, one (2.3%) patient had no lesions, five (11.4%) had solitary focal lesions and 17 (38.6%) had >10 lesions. The lesion number of type I was 127 (27.85%); type II was 286 (62.72%); type III was 22 (4.82%); and type IV 21 (4.61%). The lesions were mainly distributed in the peripheral (92.11%) and posterior (71.71%; type I 51.17%) parts of the lung. The mean±sd size of type I was 1.37±1.08 cm (range 0.34–8.53 cm), significantly smaller than that of type II (2.12±2.00 cm, 0.3–13.53 cm; p<0.001) but not statistically different from type IV (1.52±0.88 cm, 0.38–3.12 cm; p=0.2553). The size of type II was significantly smaller than that of type III (4.7±2.58 cm, 1.36–11.90 cm; p<0.001) but not statistically different from type IV (p=0.4632). The size of type III was also significantly larger than that of type IV (p<0.001). The CT score was 38.44±34.56 (range 0–136.13). Finally, there were 11 indicators in the multiple linear regression model to evaluate their linear relation to the CT score (abnormal rate ≥40%; without multicollinearity): lymphocyte, CD4+ T-cell, CD8+ T-cell, CRP, TP, ALB, ALB/globin, PAB, LDH, HDL and LDL. The adjusted R2 was 0.509. Only CD4+ T-cell (B=−25.738; p=0.018), CRP (B=20.565; p=0.044) and LDH (B=23.201; p=0.010) were statistically significant in the linear regression with the CT score. 28.95% lesions had vessel expansion, while 40.13% had air bronchogram. 6.82% patients had mediastinal lymphadenopathy, while 6.82% had pleural effusion (bilateral two out of 44; unilateral one out of 44). All patients obtained follow-up CT at least once. During our study period, we recorded the first follow-up CT of all patients (interval of 2–7 days; median 4 days). 81.82% patients showed lesion progression, while 13.64% patients showed lesion absorption. We also recorded the first and second follow-up CT in one patient (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

A 64-year-old female. a–c) Initial computed tomography (CT) showed that lesions manifested as type II and III with pleural thickening and adhesions, mainly located in the peripheral and posterior part of the lung. d) At the 7-day follow-up CT, the lesion size had broadened and density had increased, which meant there was progression. e) Follow-up CT after a further 3 days showed lesions to be partly absorbed and fibrosis, which meant relief.

In our study, the onset symptom in most patients was fever, which was similar to SARS-CoV [8] and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV [9], but other symptoms of COVID-19 were mild. In 52.27% of patients, lymphocyte count decreased, which is valuable to the early diagnosis. Experts have suggested that COVID-19 might act mainly on lymphocytes, especially T-lymphocytes, in a similar way to SARS-CoV [10]. In many patients, CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts also decreased, which indicated that COVID-19 could attack immunocytes, leading to imbalanced immune regulation. The CD4+ T-cell counts, as well as CRP and LDH, had linear regression with regard to the severity of pulmonary lesions on CT, which has not been previously depicted. Significantly, those indicators enrolled in the model were the first value and divided as the category variable, which might indicate the patient's onset pulmonary severity levels. Similar to MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV infection [9], some patients presented elevated levels of liver aminotransferase, which may indicate the potential liver injury [11].

13.64% of patients' pulmonary lesions were mild in the early stage, making them easy to be misdiagnosed. All the lesions of COVID-19 have a predominant distribution in the peripheral part of the lung (92.11%). Pulmonary lesions, with the exception of type I, have a predominant distribution in the posterior part of the lung, which is vital to early diagnosis and has not been depicted previously. In the early stage of COVID-19, most pulmonary lesions represent as type II, followed by type I, while type III and type IV are rare. The size of lesion that represents as type IV is small, nearly to that of type I and II, in contrast to advanced COVID-19, which may show wide consolidation [7]. Consolidation is also common in avian influenza A (H7N9) pneumonia [12], bacterial pneumonia, invasive fungal disease [13] and some other virus pneumonias [14]. 81.82% of patients' follow-up CT showed disease progression, which is in accordance with the time course of lung changes of the greatest severity; approximately 10 days after onset of symptoms [15].

In conclusion, fever is the main onset symptom of COVID-19. Decreased lymphocyte count is an important indicator for diagnosis. The features of early stage COVID-19 include GGO-based lesions with rare small size consolidation mainly distributed in the peripheral and posterior part of the lung. Some patients' pulmonary lesions are small and focal, which should capture physician's attention. The level of decreased CD4+ T-cells, and the elevated CRP and LDH may prompt the severity of CT imaging.

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere wishes and greatest respect to the front-line workers who are fighting against COVID-19.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: S. Yang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Shi has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Lu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Xu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Li has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Qian has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Jiang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Hua has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Ding has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Song has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Shen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Lu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Shan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Zhang has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission, grant 18411967100. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO Director-General's remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. 2020. www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020 Date last accessed: 11 Feb 2020.

- 2.Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020; 579: 265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group[J]. BioRxiv 2020; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.07.937862]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 2020; 395: 689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report - 33 https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ Date last accessed: February 23, 2020.

- 6.Xinhua. Virus-hit Wuhan speeds up diagnosis of patients https://enapp.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202002/06/AP5e3be074a3103a24b1106147.html Date last accessed: February 6, 2020.

- 7.Song F, Shi N, Shan F, et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 2020; 295; 210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui DS, Wong PC, Wang C. SARS: clinical features and diagnosis. Respirology 2003; 8: Suppl., S20–S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020; 395: 507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai XQ, Hu LF, Zhang Y, et al. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. bioRxiv 2020; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.03.931766]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q, Zhang Z, Shi Y, et al. Emerging H7N9 influenza A (novel reassortant avian-origin) pneumonia: radiologic findings. Radiology 2013; 268: 882–889. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen W, Xiong X, Xie B, et al. Pulmonary invasive fungal disease and bacterial pneumonia: a comparative study with high-resolution CT. Am J Transl Res 2019; 11: 4542–4551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo HJ, Lim S, Choe J, et al. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics 2018; 38: 719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology 2020; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200370]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00407-2020.Shareable (321.7KB, pdf)