Abstract

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of milk intake, milk composition, and nutrient intake on piglet growth in lactation and body composition at weaning. To evaluate the body composition of piglets, data from one experiment (44 Danish Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc piglets) were used to develop prediction equations for body pools of fat, protein, ash, and water based on live weight and deuterium dilution space (exp. 1). Furthermore, a total of 294 piglets (Danish Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc) from 21 sows of second parity were included in a second experiment (exp. 2). In exp. 2, piglet live weight was recorded on days 3, 10, 17, and 25 of lactation. On the same days, the milk intake and body composition were measured, using the deuterium oxide (D2O) dilution technique. Piglet weight gain was highly positively correlated with the intake of milk and the intake of milk constituents each week and on an overall basis having r values ranging from 0.65 to 0.93 (P < 0.001). When evaluating regressions for piglet growth, the milk intake in combination with the milk protein concentration explained 85% and 87% of the total variation in piglet gain in the second and third week of lactation, respectively, whereas milk intake was the only predictor of piglet gain in the first week of lactation explaining 81% of the variation. Fat, protein, and energy retention rates were all highly positively correlated with the daily intake of milk and intake of milk nutrients with r values ranging from 0.76 to 0.94 (P < 0.001). Piglet gain and retention rates were rather weakly correlated with the milk composition with r values ranging from 0.01 to 0.50 (being either negative or positive). Curvilinear response curves were fitted for live weight gain and body fat content at weaning in response to milk protein concentration, showing that live weight gain was slightly greater and body fat content was slightly lower at 4.9% milk protein, but it should be emphasized that the quadratic effects did not reach significance. Body fat content at weaning was positively related with the intake of milk (R2 = 0.44, P < 0.001) and milk fat (R2 = 0.46, P < 0.01). In conclusion, milk intake had a major impact on the piglet growth rate, and milk fat intake greatly influenced the body fat percentage at weaning, whereas milk composition per se only played a minor role for these traits.

Keywords: lactation, piglet body composition, piglet growth, retention rates, suckling piglet, weaning

Introduction

The young piglet has a high growth potential, but the sow milk yield in combination with the nutrient composition is insufficient to achieve maximal growth of sow-reared piglets (Noble et al., 2002). Between birth and weaning, piglets suckling high-yielding sows grow on average approximately 250 g/d (Hojgaard et al., 2019b, 2019c), but this growth rate is far below their biological potential. It has been known for decades that young, artificially reared piglets having ad libitum access to milk replacers can grow more than 450 g/day (Harrell et al., 1993), and perhaps today’s modern genotypes can grow even faster.

Evolutionarily, a high fat content of sow milk was most likely favorable for piglets to increase their body fat content and thereby increase the survivability of piglets (Harrell et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1995). However, it was suggested by several authors (Campbell and Dunkin, 1983; Noblet and Etienne, 1987; Williams et al., 1995) that milk protein concentration or milk protein to energy ratio is too low to support maximal growth of lean genotype piglets. Increasing dietary protein concentration in sow diets leads to greater milk casein and milk protein concentrations (Strathe et al., 2017; Hojgaard et al., 2019b), but it is not known what the optimal concentration of milk protein is for piglet growth. Consequently, it is important to understand whether milk intake, milk composition, or daily intake of milk nutrients limits piglet growth. Due to genetic selection, litter size is larger, and piglets are smaller at birth and at weaning. Milk intake of piglets may be estimated as 4.0× litter average daily gain (Whittemore and Morgan, 1990). However, it is unclear how efficient modern piglets in large litters convert milk into growth because hyper prolificacy causes piglets to be born more vulnerable with a lower birth weight and concomitantly competition among littermates is greater in large litters, which also leads to greater heat loss.

Retention of energy in suckling piglets is highly important to increase the robustness of piglets at weaning. Weaners are challenged due to the low intake of dry feed (Poulsen, 1995), which causes a negative energy balance. However, retention of energy cannot be evaluated from the weight gain of piglets because 1 g of retained body fat contains 7- to 8-fold more energy than 1 g of retained muscle. Indeed, lean growth consists of approximately 19% protein and 81% water (Noblet and Etienne, 1987) and contributes greatly to the daily growth rate but little to the energy retention. Therefore, knowledge of piglet body composition at weaning and the quantitative accretion of body protein and body fat are highly important.

Two studies were carried out of which the first aimed at developing prediction equations of body composition using the deuterium dilution technique, and the second aimed at characterizing the impact of milk intake, milk composition, and milk nutrient intake on piglet growth in lactation and body composition at weaning. It was hypothesized that the optimal milk protein concentration increases piglet growth but decreases piglet body fat percentage at weaning, whereas both traits are favored by a high milk intake.

Materials and Methods

The experimental protocols were approved by the Danish Animal Experimentation Inspectorate. Animal housing and rearing followed the Danish laws and regulations for the humane care and use of animals in research (The Danish Ministry of Justice, 1995).

Animals and experimental procedures—exp. 1

In total, 44 piglets from five sows of second parity (Danish Landrace × Danish Yorkshire; DanBred, Herlev, Denmark) were included in exp. 1. The sows were artificially inseminated with DanBred Duroc semen (Hatting KS, Horsens, Denmark) resulting in Danish Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc progeny. The feeding strategy of sows and management procedures were described in detail by Hu et al. (2020). Piglets were weighed and enriched with deuterium oxide (D2O) at day 28 (weaning). Blood was sampled 2 h after enrichment to calculate deuterium dilution space (see equation 1 in Calculations), and, subsequently, the piglets were euthanized. The entire gastrointestinal tract was emptied for digesta, and the empty body, including organs and the gastrointestinal tract, was grinded to obtain a homogenous mass of the empty body. A representative sample from each piglet was analyzed according to the standard procedures for the concentration of dry matter (DM), ash, and protein (nitrogen × 6.25). The body fat concentration was calculated by difference, assuming body fat, body protein, and body ash sum up to 100% DM.

Animals and experimental procedures—exp. 2

In total, 294 piglets from 21 sows of second parity (Danish Landrace × Danish Yorkshire; DanBred, Herlev, Denmark) were used in exp. 2. The sows were artificially inseminated with DanBred Duroc semen (Ornestation Mors, Redsted, Denmark) resulting in Danish Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc progeny. The data were obtained from sows exposed to the same dietary treatments, feeding system, feeding strategy, housing conditions, and management procedures as described in detail by Hojgaard et al. (2019b). Though, it should be emphasized that in the current study, the milk chemical composition of the individual sows was regarded the dietary treatment for the piglets within a litter, whereas the dietary protein fed to the sows during lactation differed from 96 to 152 g/kg of standardized ileal digestible crude protein to maximize the variation in milk protein.

Litters were standardized to 14 piglets at day 3 ± 2. On days 3, 10, 17, and 25 ± 2 days, individual piglet live weight was recorded, and milk samples were collected. Before milking, piglets were removed from the sow for at least 30 min. Afterward, sows were given 2 mL i.m. injection of oxytocin (10 IU/mL; Oxytocin “Intervet” vet, MSD Animal Health, Copenhagen V, Denmark) to induce milk letdown. At each sampling day, each sow had 50 mL of milk drawn manually from four to five teats evenly distributed along the udder. Each sample was filtered through gauze and stored at −20 °C until chemical analysis. The milk samples were analyzed for DM, lactose, fat, and true protein by infrared spectroscopy (MilkoScan 4000, Foss Electric, Hillerød, Denmark).

To determine the body composition and milk intake of piglets, the deuterium dilution technique was used as described by Theil et al. (2002). Three littermates were selected at random from 21 litters at day 3 in lactation and were followed throughout lactation (n = 63 piglets). On days 3, 10, 17, and 25 ± 2 days, the piglets were enriched with D2O (Sigma Aldrich, Brøndby, Denmark) in the neck by intramuscular injection of 1 g of D2O solution (10%) per kg live weight (at day 3) or 0.5 g of D2O solution (20%) per kg live weight (at days 10 and 17) or 0.25 g of D2O solution (40%) per kg live weight (at day 25). To calculate the mass of the D2O infusate injected in the piglet, the weight of the syringe was recorded before and after injection. Blood was sampled before injection of D2O and 1 h after injection to be able to calculate the deuterium dilution space (see equation 1 in Calculations) and the total body water (TBW) (see equation 2 in Calculations) of each enriched piglet. Blood was drawn from the jugular vein and collected into serum vacutainer tubes (5 mL Vacuette Serum; Greiner Bio-One International GmbH, Kremsmünster, Austria). The samples were centrifuged at 1,558 × g for 12 min at 4 °C. Serum was harvested and stored at −20 °C until analysis. The milk intake of individual piglets was calculated in weeks 1 (days 3 to 10), 2 (days 10 to 17), and 3 (days 17to 25) of lactation (see equation 4 in Calculations).

Body pools of water, fat, ash, and protein were predicted using the prediction equations from exp. 1 based on live weight and the deuterium dilution space.

Calculations

The volume of the piglet body, of which the D2O is distributed into, is referred to as the deuterium dilution space (Q) measured at equilibration (1 h after enrichment). The deuterium dilution space is calculated according to equation 1 which was modified after Theil et al. (2002):

| (1) |

where (g) is the mass of the D2O infusate injected in the piglet, (g/mol) is the molecular weight of the infusate, is the molecular weight of distilled water (18.01499 g/mol) reflecting the molecular weight of the water in the piglet before enrichment, is the atomic fraction of D2O in the infusate, is the atomic fraction of D2O in serum before the dose of the infusate was injected into the piglet, is the atomic fraction of D2O in serum after equilibration (1 h after enrichment with the infusate).

The TBW content at equilibration was calculated according to equation 2 which was Q divided by a correction factor for non-water exchange because D2O overestimates the water pool. The overestimation in growing pigs is estimated to 3% (Haggarty et al., 1994). This overestimation is much greater in sows (23%; Rozeboom et al., 1994) and indicates that the overestimation is related to the body fat percentage. Because piglets are born with a very low fat content (Pastorelli et al., 2009), it was assumed that the correction factor for non-water exchange was 1.00, 1.01, 1.02, and 1.03 for days 3, 10, 17, and 25, respectively. Therefore, the TBW pool was calculated as:

| (2) |

The body water turnover (g/d) is the daily replacement of body water. For the suckling piglet, it is the daily intake of water originating from milk and metabolically produced water under the assumption that the piglet does not drink water from the drinking nipple in the pen. The water turnover was calculated using equation 3, which was a modification of the equations reported by Coward et al. (1982) and Theil et al. (2002):

| (3) |

where TBW1 was the TBW at equilibration and TBW2 was the TBW 1 wk later. The atomic fractions of D2O in serum after equilibration and 1 wk later are given as and , respectively, whereas is the atomic fraction of D2O in background serum collected at day 3 (i.e., before the first injection of D2O infusate). Atomic fractions were calculated according to Speakman (1997). D2O is equally distributed in all body water compartments leaving the body as liquid but not within water leaving the body as vapor (a gas). Data on growing pigs suggested that 31% of the TBW content undergoes fractionation due to transepidermal and respiratory water losses through water evaporation containing less deuterium than the body water (Haggarty et al., 1994). Consequently, the concentration of deuterium in the body water left behind will rise, and if it is assumed that the gaseous form of water leaving the piglet has the same concentration of deuterium as the liquid form left behind, then the body water turnover will be underestimated. Therefore, the fraction which undergoes fractionation (31%) is corrected by the fractionation factor (f = 0.941) for deuterium between the gaseous and liquid form of water at 37 °C according to Haggarty et al. (1988) when calculating the daily body water turnover.

The daily milk intake of enriched piglets was calculated from the body water turnover corrected for the realized water fraction of milk using equation 4 which was modified after Theil et al. (2002) and Devillers et al. (2004).

| (4) |

in which the realized water fraction of milk was calculated from the potential metabolic water fraction of milk (PMWFM) and the potential metabolic water fraction in milk protein and fat deposited in the body (PMWFD) as PMWFM–PMWFD. The PMWFM was calculated according to Theil et al. (2002) and is the actual water fraction of milk including metabolically produced water under the assumption that all milk solids were oxidized. However, some of the milk solids are not oxidized but deposited as protein and fat in the body and hence do neither contribute to metabolic water nor contribute to the dilution of D2O in the piglet. In exp. 2, the realized water fraction of milk was on average 0.91 [0.90; 0.92].

The concentration of GE in milk was estimated from the equation described by Chwalibog (2006):

| (5) |

in which 23.9, 38.9, and 16.3 refer to the energy content (in kJ) per gram of protein, fat, and lactose, respectively. The contents of protein, fat, and lactose refer to the chemical composition of sow milk (in g/100 g of milk).

Statistical methods

All calculations and statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS (Enterprise Guide 7.1; SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All Pearson correlation coefficients and regression models were fitted using the SURVEYREG procedure, including sow as a cluster variable to account for the clustering of piglets within the same litter in the denominator degrees of freedom. Outliers were excluded when the externally studentized residuals were outside ±3 standard deviations. Significant predictors in the regression models were determined through backward elimination. Statistical significance was declared at P ≤ 0.05. Descriptive statistics of the data were reported as the mean ± SD and the range (minimum; maximum) using PROC MEANS.

Experiment 1

Linear regression models predicting body composition of piglets using live weight and deuterium space were fitted. Even though the deuterium space was not a significant (P ≤ 0.05) predictor in all models, the full models, including live weight and deuterium space, and the reduced models, including only live weight, are presented.

Experiment 2

The milk composition, piglet characteristics, and piglet body composition were analyzed day by day or weekly using the MIXED procedure of SAS with fixed effect of days in milk and sow as a random effect. When analyzing milk composition, each sow was considered the experimental unit, whereas when analyzing piglet characteristics, each piglet was considered the experimental unit and was included as a random effect as well. The Tukey–Kramer test was used in multiple comparisons of means to adjust the P-values.

Results

Experiment 1

Descriptive statistics of the 44 piglets in exp. 1 are shown in Table 1, and the prediction equations for estimating body pools of ash, protein, water, and fat from live weight and from both live weight and deuterium space are presented in Table 2. The best equation for predicting body fat and body water pools included both live weight and deuterium space as independent variables which accounted for 91% and 99% of the variation in body fat and body water pools at weaning, respectively. Body ash and body protein pools were best predicted using live weight as the only predictor which accounted for 61% and 97% of the variation in body ash and body protein pools at weaning, respectively. Including deuterium space did not add further to the explanation of the variation in body ash and body protein. The developed prediction equations were subsequently used to predict the body composition of piglets in exp. 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of piglet characteristics at weaning (28 d in lactation), n = 44: exp. 1

| Item | Mean ± SD[min; max] |

|---|---|

| Body weight | |

| Live weight, g | 8,567 ± 1,340 |

| [5,747; 11,797] | |

| Chemical composition | |

| Fat, % | 12.3 ± 1.8 |

| [7.8; 15.3] | |

| Protein, % | 15.9 ± 0.44 |

| [14.8; 16.7] | |

| Ash, % | 3.4 ± 0.37 |

| [2.8; 4.2] | |

| Water, % | 68.4 ± 1.65 |

| [65.8; 72.0] |

Table 2.

Prediction equations to estimate pools of total body protein, fat, ash, and water using live weight and deuterium space at weaning, n = 44: exp. 1

| Regression coefficients (bi)1 | Model fit2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response, Y | b0 | Live weight | Deuterium space | RMSE | R 2 |

| Fat, g | −242 ± 173 | 0.640 ± 0.088** | −0.692 ± 0.143* | 86.9 | 0.91 |

| −585 ± 163 | 0.193 ± 0.016** | 117 | 0.84 | ||

| Protein, g | −3.47 ± 56.3 | 0.155 ± 0.037* | 0.0067 ± 0.060 | 36.6 | 0.97 |

| −0.09 ± 33.9 | 0.159 ± 0.004** | 36.2 | 0.97 | ||

| Ash, g | 43.6 ± 32.0 | 0.020 ± 0.016 | 0.013 ± 0.024 | 30.9 | 0.61 |

| 50.2 ± 28.5 | 0.028 ± 0.004* | 30.6 | 0.61 | ||

| Water, g | 286 ± 139 | 0.274 ± 0.080* | 0.532 ± 0.130* | 75.2 | 0.99 |

| 555 ± 156 | 0.617 ± .017*** | 96.7 | 0.99 |

1The model was or , where regression coefficients, bi, were given as least squares estimates ± standard error to either piglet live weight, X1, or deuterium space, X2.

2The model fit was evaluated based on root mean square error (RMSE) and R2. In models with more than one predictor variable, the adjusted R2 was given.

*P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001; variable is a significant predictor.

Experiment 2

Three sows were excluded from this study: one sow due to gastric ulcer and two sows due to postpartum dysgalactia syndrome. Furthermore, three litters were not weighed individually and included in deuterium measurements at day 25 due to practicality. Therefore, the results on days 3, 10, and 17 were based on data from 18 sows and litters, and the results on day 25 were based on data from 15 sows and litters. Growth of individual piglets and milk intake results in weeks 1 (days 3 to 10) and 2 (days 10 to 17) were, therefore, based on data from a maximum of 54 piglets, whereas growth and milk intake in week 3 (days 17 to 24), overall growth, and body retention throughout lactation were based on data from a maximum of 45 piglets. When results were collected for all littermates in each litter, a total of 252 piglets were included, except at day 25 when 210 piglets were included.

Piglet growth

The chemical composition of milk changed with the progress of lactation (P < 0.001; Table 3). The milk contents of DM, fat, protein, and GE were greater at 3 d in milk than at 10, 17, and 25 d in milk, respectively. The milk lactose content increased, as lactation progressed.

Table 3.

Results on milk composition and piglet performance: exp. 2

| Item | Days in milk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 1 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 25 | ||

| LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | P-value | ||

| Milk composition | ||||||

| DM, % | 18 (15) | 18.67 ± 0.28a | 17.52 ± 0.25b | 17.06 ± 0.26b | 16.63 ± 0.28b | <0.001 |

| [16.7; 21.85] | [16.18; 19.96] | [15.94; 18.97] | [15.44; 17.83] | |||

| Fat, % | 18 (15) | 7.71 ± 0.26a | 6.94 ± 0.24ab | 6.47 ± 0.24cb | 5.82 ± 0.26c | <0.001 |

| [6.15; 10.9] | [5.77; 9.94] | [5.7; 7.8] | [4.96; 6.77] | |||

| Protein, % | 18 (15) | 5.47 ± 0.1a | 4.56 ± 0.09b | 4.47 ± 0.09b | 4.69 ± 0.1b | <0.001 |

| [4.49; 6.62] | [3.46; 5.44] | [3.48; 5.41] | [3.82; 5.66] | |||

| Lactose, % | 18 (15) | 4.88 ± 0.04c | 5.19 ± 0.04b | 5.31 ± 0.04ab | 5.43 ± 0.04a | <0.001 |

| [4.43; 5.43] | [4.76; 5.44] | [4.99; 5.68] | [5.27; 5.6] | |||

| GE, kJ/100g | 18 (15) | 503 ± 9.5a | 458 ± 8.6b | 444 ± 8.9b | 427 ± 9.2b | <0.001 |

| [435; 631] | [419; 539] | [403; 514] | [385; 468] | |||

| Piglet performance | ||||||

| Milk intake, g/d2,3 | 54 (45) | 871 ± 36b | 1,201 ± 35a | 1,217 ± 36a | <0.001 | |

| [484; 1,277] | [595; 1,588] | [718; 1,684] | ||||

| Live weight gain, g/day3 | 252 (210) | 236 ± 5.34b | 270 ± 5.41a | 275 ± 5.63a | <0.001 | |

| [46; 358] | [69; 441] | [71; 418] | ||||

| Conversion ratio, g milk/ g gain3 | 54 (45) | 3.92 ± 0.1b | 4.55 ± 0.1a | 4.77 ± 0.1a | <0.001 | |

| [3.21; 5.27] | [3.65; 6.72] | [3.79; 7.24] | ||||

| Live weight, g | 252 (210) | 1,845 ± 85d | 3,442 ± 85c | 5,316 ± 86b | 7,561 ± 88a | <0.001 |

| [1,200; 2,812] | [1,654; 5,102] | [2,871; 7,301] | [4,320; 10,160] | |||

| Litter size4 | 18 | 14.0 ± 0.00 | 13.4 ± 0.59 | 13.0 ± 0.58 | 12.9 ± 0.64 | – |

| [14; 14] | [12; 14] | [12; 14] | [12; 14] |

1Number of observations per day in milk. In parenthesis is given the number of observations at day 25 (week 3).

2The milk intake was measured by the deuterium dilution technique.

3Live weight gain, milk intake, and conversion ratio were determined weekly, i.e., at days 3 to 10, 10 to 17, and 17 to 25, respectively.

4Litter size is given as mean ± SD.

a,b,c,dSuperscript letters within a row indicate a significant difference between days in milk.

The milk intake of piglets increased from an average of 871 g/d in week 1 to 1,201 and 1,217 g/d in weeks 2 and 3, respectively (P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean live weight gain was lower (P < 0.001) in week 1 than in weeks 2 and 3 and amounted to 236, 270, and 275 g/d, respectively. The milk to gain conversion ratio (grams of milk intake per gram of piglet gain) was lower (P < 0.001) in week 1 than in weeks 2 and 3, and the ratios were on average 3.92, 4.55, and 4.77 g of milk per gram of piglet gain in weeks 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The individual live weight of piglets increased from an average of 1,845 g at day 3 in lactation to 7,561 g at day 25 in lactation (P < 0.001).

The Pearson correlations between the chemical components in milk and piglet gain at all stages of lactation were rather weak, ranging from 0.01 to 0.28 (being either negative or positive; Table 4). In week 2 (r = +0.28; P < 0.05) and week 3 (r = +0.26; P < 0.05) of lactation, the piglet gain was positively correlated with the milk protein concentration. Contrarily, the piglet gain was negatively correlated with lactose in week 3 of lactation (r = –0.27; P < 0.05) and on an overall basis (r = –0.24; P < 0.01). The piglet weight gains in weeks 1, 2, and 3 were highly positively correlated with the milk intake in each week and overall for the entire lactation period, having the Pearson correlations ranging from 0.90 to 0.93 (P < 0.001). Furthermore, piglet weight gain was highly positively correlated with the intake of milk constituents in each week and on an overall basis, having the Pearson correlations ranging from 0.65 to 0.93 (P < 0.001) with the milk fat intake being least correlated with the weight gain, having the Pearson correlations ranging from 0.65 to 0.85.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients between variables related to piglet average daily gain: exp. 2

| Piglet gain, g/day days 3 to 10 | Piglet gain, g/day days 10 to 17 | Piglet gain, g/day days 17 to 25 | Piglet gain, g/day days 3 to 25 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | n | r | P-value | n | r | P-value | n | r | P-value | n | r | P-value |

| Milk composition | ||||||||||||

| DM, % | 198 | –0.19 | NS | 215 | 0.11 | NS | 180 | 0.19 | NS | 153 | 0.01 | NS |

| Fat, % | 198 | –0.14 | NS | 202 | –0.10 | NS | 180 | 0.08 | NS | 153 | –0.12 | NS |

| Protein, % | 172 | –0.07 | NS | 229 | 0.28 | * | 194 | 0.26 | * | 167 | 0.15 | NS |

| Lactose, % | 223 | –0.06 | NS | 203 | –0.25 | NS | 181 | –0.27 | * | 167 | –0.24 | ** |

| Milk and nutrient intake1 | ||||||||||||

| Milk intake, g/d | 46 | 0.90 | *** | 51 | 0.90 | *** | 44 | 0.91 | *** | 34 | 0.93 | *** |

| DM intake, g/d | 41 | 0.85 | *** | 48 | 0.90 | *** | 41 | 0.92 | *** | 31 | 0.93 | *** |

| Fat intake, g/d | 41 | 0.65 | *** | 45 | 0.85 | *** | 41 | 0.83 | *** | 31 | 0.84 | *** |

| Protein intake, g/d | 37 | 0.87 | *** | 51 | 0.90 | *** | 44 | 0.88 | *** | 28 | 0.87 | *** |

| Lactose intake, g/d | 46 | 0.88 | *** | 45 | 0.87 | *** | 41 | 0.90 | *** | 31 | 0.90 | *** |

1The milk intake was measured by the deuterium dilution technique, and the intake of fat, protein, and lactose was calculated by multiplying the concentration with the intake of milk.

*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; NS, not significant.

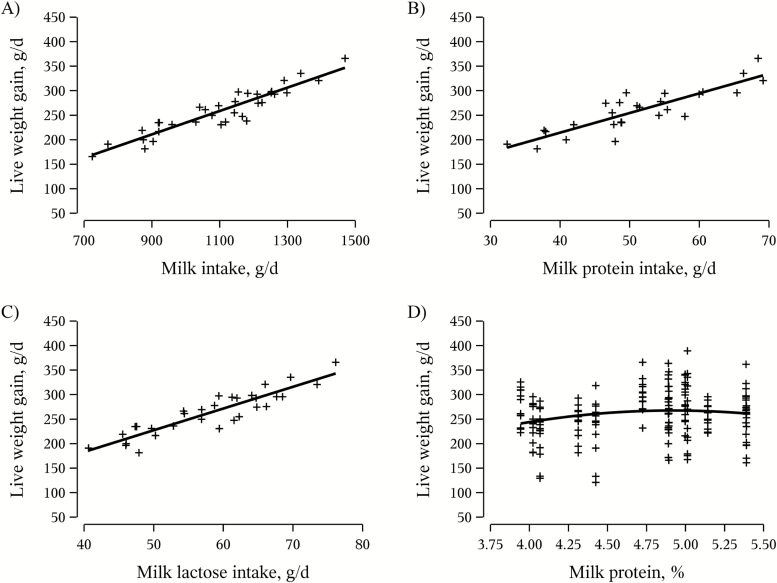

The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 5, indicating that the milk intake explained 81% of the variation in piglet gain in the first week of lactation. In the second and third week of lactation, and on an overall basis, the milk intake in combination with the milk protein concentration explained 85%, 87%, and 89% of the variation in piglet gain, respectively. However, when evaluating the milk nutrient intakes as independent variables, the milk protein intake and lactose intake were the only significant predictors explaining between 82% and 87% of piglet gain throughout the lactation. Piglet live weight gain from days 3 to 25 increased with increasing daily milk intake (Figure 1A; P < 0.001), milk protein intake (Figure 1B; P < 0.001), and milk lactose intake (Figure 1C; P < 0.001). Fitting a curvilinear response of live weight gain in response to milk protein concentration suggested that 4.9% milk protein may maximize piglet growth, but it should be emphasized that the live weight gain of piglets was rather constant within 4.0% to 5.5% of milk protein, and neither the linear (P = 0.48) nor the quadratic term (P = 0.50) were significant (Figure 1D).

Table 5.

Regression models for piglet live weight gain: exp. 2

| Response, Y | n | Regression model1, 2, 3 | R 2 (4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live weight gain days 3 to 10, g/d | 41 | 2.62 ± 18.1 + 0.26 ± 0.02 × milk intake, g/d | 0.81 |

| 37 | −10.7 ± 19.0 + 2.39 ± 0.90 × milk protein intake, g/d + 3.02 ± 0.82 × milk lactose intake, g/d | 0.82 | |

| Live weight gain days 10 to 17, g/d | 51 | −112 ± 23.4 + 27.3 ± 4.69 × milk protein, % + 0.21 ± 0.01 × milk intake, g/d | 0.85 |

| 45 | 1.23 ± 14.4 + 2.52 ± 0.38 × milk protein intake, g/d + 2.04 ± 0.35 × milk lactose intake, g/d | 0.84 | |

| Live weight gain days 17 to 25, g/d | 44 | −151 ± 36.9 + 23.2 ± 8.12 × milk protein, % + 0.25 ± 0.02 × milk intake, g/d | 0.87 |

| 41 | −58.2 ± 22.1 + 2.16 ± 0.65 × milk protein intake, g/d + 3.06 ± 0.73 × milk lactose intake, g/d | 0.87 | |

| Live weight gain days 3 to 25, g/d | 28 | −70.2 ± 45.1 + 14.1 ± 6.3 × milk protein, % + 0.24 ± 0.02 × milk intake, g/d | 0.89 |

| 28 | 2.60 ± 22.9 + 1.93 ± 0.50 × milk protein intake, g/d + 2.75 ± 0.33 × milk lactose intake, g/d | 0.87 |

1The model was , where regression coefficients, b1–i, were given as least squared estimates ± standard error to X1–i.

2Two regression models were given for each response variable. The first model allowed the inclusion of milk intake and milk constituents, and the second equation allowed the inclusion of intake of milk nutrients. Significant predictors in the regression models were determined through backward elimination. All variables included in the models were significant at a 0.05-level.

3The milk nutrient concentrations were the average concentrations based on milk samples collected on days 3, 10, 17, and 25 in lactation. The milk intake was measured by the deuterium dilution technique.

4In models with more than one predictor variable, the adjusted R2 was given. The R2 indicates how much of the variation in the response is explained by the included variables, and the more of the variation that is explained, the better.

Figure 1.

Development in piglet live weight gain days 3 to 25 in response to mean daily milk intake from days 3 to 25 (Panel A: live weight gain, g/d = −4.13 ± 15.3 + 0.24 ± 0.015 × milk intake, R2 = 0.87), mean milk protein intake from days 3 to 25 (Panel B: live weight gain, g/d = 53.9 ± 23.2 + 4.01 ± 0.47 × milk protein intake, R2 = 0.75), mean milk lactose intake from days 3 to 25 (Panel C: live weight gain, g/d = 5.64 ± 20.7 + 4.43 ± 0.37 × milk lactose intake, R2 = 0.82), and mean milk protein concentration from days 3 to 25 (Panel D: live weight gain, g/d = −408 ± 869 + 275 ± 377 × milk protein − 27.9 ± 40.5 × milk protein × milk protein, R2 = 0.02). Regression coefficients are given as least squared estimates ± standard error.

Piglet body composition

The body water concentration dropped curvilinearly (P < 0.001; Table 6) from 75.5% to 67.0%, as piglet live weight increased from 1,880 to 7,365 g. Oppositely, the body fat concentration increased curvilinearly (P < 0.001) from 1.94% to 13.0% from 3 to 25 d in milk, while the body ash and protein contents were rather constant even though the body ash content was slightly greater at day 3 than at day 25 (5.3% vs. 3.5%; P < 0.001), and the body protein content was slightly lower at day 3 than at day 25 (15.82 vs. 15.91%; P < 0.001). Piglet body fat content at weaning increased with increasing daily milk intake (Figure 2A; P < 0.001) and increasing milk fat intake (Figure 2B; P < 0.01). Fitting a curvilinear response to milk protein concentration suggested that body fat content was minimized at 4.9% milk protein, but it should be emphasized that it was rather constant within 4.0% to 5.5% of milk protein, and neither the linear term (P = 0.36) nor the quadratic term (P = 0.38) were significant (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the body fat content of piglets at weaning was not at all related to milk fat concentration per se within 6.0% to 7.5% of milk fat (Figure 2D; P = 0.74).

Table 6.

Results on piglet body composition, n = 54 (45 at day 25): exp. 21

| Item | Days in milk | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 10 | 17 | 25 | ||

| LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | LSMean ± SEM [mini; max] | LSMean ± SEM [min; max] | ||

| Piglet characteristics | |||||

| Live weight, g | 1,880 ± 132d | 3,450 ± 132c | 5,238 ± 123b | 7,365 ± 137a | <0.001 |

| [1,449; 2,669] | [1,670; 4,963] | [3,360; 7,169] | [4,320; 10,160] | ||

| Piglet body composition | |||||

| Fat, % | 1.94 ± 0.26d | 8.7 ± 0.26c | 11.5 ± 0.26b | 13.0 ± 0.28a | <0.001 |

| [1.6; 6.0] | [2.5; 12.6] | [6.2; 14.7] | [9.3; 15.0] | ||

| Protein, % | 15.82 ± 0.003d | 15.86 ± 0.003c | 15.89 ± 0.003b | 15.91 ± 0.003a | <0.001 |

| [15.77; 15.87] | [15.84; 15.90] | [15.86; 15.92] | [15.89; 15.93] | ||

| Ash, % | 5.3 ± 0.04a | 4.1 ± 0.04b | 3.7 ± 0.04c | 3.5 ± 0.53d | <0.001 |

| [4.6; 6.0] | [3.8; 4.6] | [3.5; 4.2] | [3.3; 3.9] | ||

| Water, % | 75.5 ± 0.29a | 69.1 ± 0.28b | 67.6 ± 0.28c | 67.0 ± 0.30c | <0.001 |

| [71.6; 79.6] | [65.6; 77.7] | [64.2; 75.5] | [64.1; 70.3] |

1The prediction equations from exp. 1 based on live weight and the deuterium dilution space were used to estimate pools of body fat, protein, and ash, whereas the body water content was determined based on equation 2 given in Calculations.

a,b,c,dSuperscript letters within a row indicate a significant difference between days in milk.

Figure 2.

Development in piglet body fat percentage at weaning in response to mean daily milk intake from days 3 to 25 (Panel A: body fat, % = 8.66 ± 0.89 + 0.004 ± 0.0009 × milk intake, R2 = 0.44), mean daily milk fat intake from days 3 to 25 (Panel B: Body fat, % = 8.65 ± 1.07 + 0.061 ± 0.016 × milk fat intake, R2 = 0.46), mean milk protein concentration from days 3 to 25 (Panel C: body fat, % = 37.6 ± 24.3 − 10.1 ± 10.6 × milk protein + 1.04 ± 1.14 × milk protein × milk protein, R2 = 0.04), and mean milk fat concentration from days 3 to 25 (Panel D: body fat, % = 13.9 ± 2.19 − 0.11 ± 0.33 × milk fat, R2 = 0.002). Regression coefficients are given as least squared estimates ± standard error.

Retention of body pools from 3 to 25 d in milk was on average 43.9 g/d of body fat, 41.0 g/d of body protein, 7.3 g/d of body ash, and 161 g/d of body water as shown in Table 7. The accretion rates of protein and fat were found to increase with increasing milk intake (Figure 3). Moreover, the greater the milk intake, the greater the fat retention relative to protein retention.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics on milk nutrient intake, retention of body pools, and dietary efficiencies in piglets, n = 45: exp. 2

| Item | Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|

| [min; max] | |

| Milk nutrient intake, days 3 to 251 | |

| DM, g/d | 191 ± 5.5 |

| [124; 254] | |

| Fat, g/d | 73.1 ± 2.0 |

| [51.2; 99.2] | |

| Protein, g/d | 51.1 ± 1.5 |

| [32.4; 69.1] | |

| Lactose, g/d | 58.5 ± 1.6 |

| [40.6; 76.1] | |

| GE, kJ/d | 4,983 ± 149 |

| [2,947; 6,728] | |

| Retention of body pools, days 3 to 25 | |

| Fat, g/d | 43.9 ± 1.5 |

| [24.4; 67.3] | |

| Protein, g/d | 41.0 ± 1.2 |

| [26.4; 58.4] | |

| Ash, g/d | 7.3 ± 0.22 |

| [4.7; 10.4] | |

| Water, g/d | 161 ± 5.3 |

| [93; 232] | |

| Energy, kJ/d | 2,719 ± 87 |

| [1,602; 4,073] | |

| Dietary efficiencies, days 3 to 25 | |

| Fat retained/fat intake, % | 60.6 ± 1.1 |

| [47.6; 72.9] | |

| Protein retained/protein intake, % | 81.5 ± 1.6 |

| [65.3; 95.2] | |

| Energy retained as fat/retained energy, % | 63.6 ± 0.32 |

| [60.6; 67.9] |

1The intake of each nutrient were based on the mean milk intake measured by the deuterium dilution technique and the mean nutrient concentrations based on milk samples collected on days 3, 10, 17, and 25 in lactation.

Figure 3.

Effect of mean daily milk intake (days 3 to 25) on accretion rates of ash, protein, and fat in suckling piglets.

Body fat, protein, and energy retention rates throughout lactation were highly correlated with piglet weight gain (r = 0.93, r = 0.99, and r = 0.97, respectively; P < 0.001; Table 8). Body fat (r = –0.45; P < 0.01), protein (r = –0.56; P < 0.001), and energy (r = –0.50; P < 0.01) retention rates were negatively correlated with the milk fat concentration. However, looking at the daily intakes of milk, milk fat, milk protein, milk lactose, and milk DM, they were all positively correlated with body fat, protein, and energy retention rates, having the Pearson correlations ranging from 0.76 to 0.94 (P < 0.001).

Table 8.

Pearson correlation coefficients between variables related to body fat, protein, and energy retention from days 3 to 25 in lactation: exp 2

| Item | Body fat retention, g/d | Body protein retention, g/d | Body energy retention, kJ/d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | r | P-value | r | P-value | r | P-value | |

| Piglet characteristics | |||||||

| Piglet weight day 3, g | 36 | 0.31 | NS | 0.07 | NS | 0.25 | NS |

| Piglet gain days 3 to 25, g/d | 36 | 0.93 | *** | 0.99 | *** | 0.97 | *** |

| Milk composition | |||||||

| DM, % | 29 | −0.33 | NS | −0.25 | NS | −0.34 | * |

| Fat, % | 29 | −0.45 | ** | −0.56 | *** | −0.50 | ** |

| Protein, % | 32 | 0.02 | NS | 0.19 | NS | 0.08 | NS |

| Lactose, % | 31 | −0.09 | NS | −0.25 | NS | −0.13 | NS |

| Milk and nutrient intake1 | |||||||

| Milk intake, g/d | 32 | 0.92 | *** | 0.93 | *** | 0.94 | *** |

| DM intake, g/d | 29 | 0.92 | *** | 0.93 | *** | 0.94 | *** |

| Fat intake, g/d | 29 | 0.88 | *** | 0.84 | *** | 0.88 | *** |

| Protein intake, g/d | 28 | 0.76 | *** | 0.87 | *** | 0.81 | *** |

| Lactose intake, g/d | 29 | 0.90 | *** | 0.90 | *** | 0.91 | *** |

1Milk intake was measured by the deuterium dilution technique, and the intake of fat, protein, and lactose was calculated by multiplying the concentration with the intake of milk.

*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; NS, not significant.

Prediction equations for body fat, protein, and energy retention rates are given in Table 9. The body fat, protein, and energy accretion rates of piglets were most precisely predicted using the live weight gain, which explained 86% of the variation in body fat retention, 99.9% of the variation in body protein retention, and 94% of the variation in body energy retention, respectively.

Table 9.

Prediction equations for body fat, protein, and energy retention in piglets measured from days 3 to 25 in lactation: exp 2

| Response, Y | n | Prediction equation1,2,3 | Model fit4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | R 2 | |||

| Body fat retention, g/d | 36 | −1.94 ± 3.58 + 0.18 ± 0.01 × live weight gain, g/d | 3.37 | 0.86 |

| 32 | −6.39 ± 4.36 + 0.046 ± 0.004 × milk intake, g/d | 3.51 | 0.85 | |

| 29 | −5.17 ± 3.99 + 0.26 ± 0.02 × milk DM intake, g/d | 3.55 | 0.84 | |

| Body protein retention, g/d | 38 | −0.009 ± 0.022 + 0.16 ± 0.00009 × live weight gain, g/d | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| 28 | −11.3 ± 7.20 + 2.27 ± 1.00 × milk protein, % + 0.038 ± 0.003 × milk intake, g/d | 2.39 | 0.89 | |

| 31 | −0.45 ± 2.33 + 0.22 ± 0.01 × milk DM intake, g/d | 2.85 | 0.85 | |

| Body energy retention, kJ/d | 36 | −77.5 ± 142 + 10.9 ± 0.58 × live weight gain, g/d | 133 | 0.93 |

| 32 | −265 ± 217 + 2.73 ± 0.21 × milk intake, g/d | 183 | 0.88 | |

| 29 | −230 ± 200 + 15.7 ± 1.19 × milk DM intake, g/d | 187 | 0.87 |

1The model was , where regression coefficients, b1–i, were given as least squared estimates ± standard error to X1–i.

2Three prediction equations were given for each response variable. The first equation allows only the inclusion of live weight gain, the second allowed inclusion of milk intake and milk constituents, and the third equation allowed the inclusion of intake of milk nutrients. Significant predictors in the regression models were determined through backward elimination. All variables included in the equations were significant at a 0.05-level.

3The milk nutrient concentrations were the average concentrations based on milk samples collected on days 3, 10, 17, and 25 in lactation. The milk intake was measured by the deuterium dilution technique.

4The model fit was evaluated based on root mean square error (RMSE) and R2. In models with more than one predictor variable, the adjusted R2 was given.

Discussion

Prediction equations for piglet body composition

Analyzing the empty body mass of piglets at weaning for DM, protein, and ash allowed the deuterium space and live weight of piglets to be used to develop prediction equations for body pools of ash, protein, water, and fat. The pools of body fat and protein at increasing age and body weight are normally best described by sigmoid curves (Danfær and Strathe, 2012). However, linear prediction equations were chosen in the current experiment because the variation in piglet weight at weaning was limited (range 5.7 to 11.8 kg). Even though neither the ash pool nor the protein pool was significantly correlated with deuterium space, the prediction equations with both live weight and deuterium space were used to predict the body composition in exp. 2 to better capture the differences not related solely to body weight differences. However, when using the prediction equation from exp. 1 to predict the body fat pool in 3-d-old piglets, a negative or unrealistically low body fat content was observed for piglets below 2,000 g of live weight. Therefore, it was decided to correct all observed body fat contents below 1.6% to that value, which was previously reported for 1-d-old piglets (Nielsen, 1973; Pastorelli et al., 2009). The negative body fat content is highly likely a consequence of the great (and negative) intercept (−242) in the prediction equation for the body fat pool, and the underlying cause is that the prediction equation was developed for piglets at weaning, while we extrapolate to 3-d-old piglets. Even though the extrapolation is not huge in terms of kilograms (or days), it is a huge extrapolation when considering the fold change in live weight (8.6 kg for weaned piglets in exp. 1; 1.9 kg for piglets at day 3 in exp. 2) and when considering the changes in body fat content, which is roughly 10-fold higher at weaning as compared with at birth. The fold change in live weight from the dataset in exp. 1 to that of piglets of 3-d-old piglets (in exp. 2) was roughly 4.5 (8.6/1.9 = 4.5).

Milk intake and milk composition

It was recently shown that the milk protein concentration increases when the dietary crude protein supply to lactating sows increases (Strathe et al., 2017; Hojgaard et al., 2019a,2019b; Pedersen et al., 2019). However, it is not known which level of milk protein is optimal for piglet growth. Therefore, it was decided to use sows fed one of the three levels of dietary crude protein in exp. 2 which represented low, intermediate, and high (96, 128, and 152 g/kg) standardized ileal digestible crude protein to ensure that the milk protein concentration varied sufficiently to demonstrate which milk factors (amount and chemical constituents) are determining factors for piglet weight gain and body composition at weaning. Curvilinear response curves could be fitted for live weight gain and body fat content at weaning in response to milk protein concentration. Although it should be emphasized that the quadratic effects in the curvilinear models did not reach significance, the live weight gain was greater, and the body fat content lower at 4.9% milk protein, which corresponded well with the milk protein concentration (4.9%) produced when high-yielding lactating sows were fed with optimal dietary protein in a study of 540 sows (Hojgaard et al., 2019b).

Based on regression analyses, the piglet growth was highly dependent on both milk intake and the concentration of milk protein, unless in early lactation. Hence, greater milk protein concentration and greater milk intake resulted in greater piglet gain in the second and third week of lactation. This may indicate that the milk protein intake was indeed limiting piglet growth in mid and late lactation, whereas, in early lactation, only the milk intake was limiting piglet growth. This agrees with the assumption that sow milk protein may be insufficient to support the maximal growth of piglets (Campbell and Dunkin, 1983; Noblet and Etienne, 1987; Williams et al., 1995). Based on the full models, it was clear that milk protein was indeed important for piglet growth, and along with either milk intake or milk lactose intake, they determined the live weight gain. The positive effect of milk lactose intake on piglet growth rate was most likely because lactose being a carbohydrate serves as an energy source and serves to fuel both heat production related to maintenance processes and extra heat related to protein retention (Theil and Jørgensen, 2016). The milk protein content supplies essential and nonessential amino acids needed for muscle growth in the suckling piglet. Protein retention is highly important for piglet growth because it binds water (Noblet and Etienne, 1987).

As a rule of thumb, approximately 4 g of milk is required for 1 g of piglet live weight gain (Whittemore and Morgan, 1990). In the current study, where the actual milk intake of piglets was measured using the deuterium dilution technique, this amounted to 4.2 g of milk required for 1 g of piglet live weight gain. This agrees reasonably well with the estimation by Whittemore and Morgan (1990). It is indeed striking that this factor has not changed much over 30 yr, especially because the genetic selection during this period has improved feed efficiency and lean meat percentage of growing pigs and profoundly increased the prolificacy of sows. However, this is most likely due to several traits that counterbalance each other. Selection for large litters has led to decreased birth weight (Beaulieu et al., 2010), and the efficiency of converting milk into growth is greater (i.e., less milk is required per gram of gain) for smaller piglets than for larger piglets because less milk is used for the maintenance. However, smaller piglets also have a greater surface to volume ratio, which increases the heat loss and this, in turn, reduces the efficiency of converting milk into growth. Moreover, the competition among littermates increases with selection for large litters, which most likely decreases the efficiency of converting milk into growth. And finally, longer lactation to compensate for lower birth weight will also decrease the efficiency of converting milk into growth. In spite of these indirect consequences of genetic selection, it is surprising to note that the overall factor (~4 g milk intake per gram of gain) seems to be roughly the same now as 30 yr ago.

When obtained on a week-to-week basis, the average amount of milk required for 1 g of live weight gain was, in the current study, estimated at 3.92, 4.55, and 4.77 g in weeks 1, 2, and 3 of lactation, respectively. The lower efficiency of converting milk into growth with the progress of lactation may be explained by the greater energy expenditure to cover maintenance. This is supported by the fact that the heat production of piglets is constant per kg0.68 (Noblet and Etienne, 1987), which means that the total heat production increases curve linearly with piglet live weight. The efficiencies of converting milk into growth in weeks 1, 2, and 3 of lactation were of the same magnitude as that reported by Theil et al. (2002), who found 3.78, 4.58, and 4.89 g milk per gram gain, respectively.

Body protein and fat retention

Mean results on the body composition of the 3- and 25-d-old suckling piglets in this study were similar to those reported by Noblet and Etienne (1987) and by Danfær and Strathe (2012). It is well-known that the most abundant changes in body composition occur between birth and weaning, and especially the body water and body fat percentages change quite rapidly during the first weeks of lactation, while both traits seemed to reach a plateau by the end of lactation (67.0% water, 13% body fat). In contrast, body ash (5.3% to 3.5%) and body protein (15.82% to 15.91%) only changed slightly throughout lactation. Quantitatively, however, all body pools of water, ash, protein, and fat increased, as live weight increased with protein and water (muscle) accretion representing on average 80% of the live weight gain from 3 to 25 d in milk. The accretion of fat and ash accounted on average for 17% and 3% of the live weight gain, respectively. The increase in live weight largely reflected protein and water retention rather than ash and fat retention because 1 g of body protein binds roughly 4.2 g of water (Noblet and Etienne, 1987). However, the large increase in body fat percentage from birth to weaning revealed that a substantial amount of ingested milk fat was retained during the suckling period. In the current study, approximately 61% of ingested fat was retained. This value was much greater than the 36% reported by Theil and Jørgensen (2016) for piglets ingesting milk replacer, which most likely reflects that milk fat in sow milk is more digestible than vegetable fat included in milk replacer formulas.

The rates of both fat and protein accretion and average daily gain were all highly interrelated, which is consistent with the results in the study of Noblet and Etienne (1987). The ratio of fat to protein gain was on average 1.09 in this study compared with 0.94 reported by Noblet and Etienne (1987). This ratio may be highly influenced by the milk intake. In the current study, the enriched piglets had a considerably greater average daily gain (254 vs. 186 g/d) than in the study by Noblet and Etienne (1987), and piglets, therefore, ingested more milk in the current study. In line with that, the fat accretion rate increases more than the protein accretion rate, as milk intake increases, which was also reported by Noblet and Etienne (1987). Consequently, the body fat content at weaning was greatest for piglets with the greatest milk intake. Interestingly, the body fat content at weaning was not affected by the milk fat concentration per se in the current study, but instead, it was clearly positively related with the daily milk fat intake. Thus, to reach a high body fat content at weaning, it is absolutely essential to have a high milk intake and a high milk fat intake. As for piglet growth, the milk composition only played a minor role in piglet body fat content.

Retention of energy in suckling piglets is of utmost importance to prepare the piglet for the weaning process during which a low feed intake, and hence a negative energy balance is often experienced by newly weaned piglets (Poulsen, 1995). Unfortunately, retention of energy cannot be evaluated appropriately from piglet weaning weight or live weight gain, partly because body fat is more energy dense than body protein (body fat contains 39.8 kJ/g while protein contains 23.9 kJ/g, respectively), and partly because 1 g of retained body fat binds only ~0.17 g of water, whereas 1 g of retained body protein binds approximately 4.2 g of body water (Noblet and Etienne, 1987). Consequently, 1 g of body fat contains 7 to 8 times more energy than 1 g of muscle mass (protein + water), and weaning weight only weakly correlates with retained energy at weaning. A high growth rate and concomitantly a high fat retention during the suckling period is wanted to ensure a robust piglet at weaning, and the D2O dilution technique is a great technique to measure body water and predict body fat pools because fat expels water. The mean body fat concentration of 13% at weaning in exp. 2 was slightly greater than the 12.3% found in exp. 1 and in Noblet and Etienne (1987) and Danfær and Strathe (2012) and could be ascribed to the high milk intake in the current study. Throughout lactation, piglets retained on average 44 g/d of fat and 41 g/d of protein. On an energy basis, this was equivalent to 64% of the energy being retained as fat and was in accordance with or slightly greater than that reported in the literature for piglets ingesting sow milk (55% to 62%), whereas it was lower (45%) in piglets raised solely on milk replacer, which is low in fat concentration as compared with sow milk (Theil and Jørgensen, 2016).

Conclusion

This study revealed that the milk intake and intake of milk constituents determine both the piglet growth rate and the body fat percentage at weaning. The milk intake was the main determinant for piglet growth rate, whereas the daily milk intake or the daily milk fat intake played a major role for the body fat content at weaning. Our study suggested that 4.9% of milk protein slightly increased piglet growth and slightly decreased piglet body fat content, but both response curves were rather flat, and the milk composition per se only played a minor role for piglet growth rate and the body fat percentage at weaning.

Acknowledgment

The research project was funded by Innovation Fund Denmark and the Danish Pig Levy Fund.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AF

atomic fraction

- DM

dry matter

- D2O

deuterium oxide

- GE

gross energy

- PMWFM

potential metabolic water fraction of milk

- PMWFD

potential metabolic water fraction in milk protein and fat deposited

- Q

deuterium dilution space

- RMSE

root mean square error

- TBW

total body water

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Beaulieu A. D., Aalhus J. L., Williams N. H., and Patience J. F.. . 2010. Impact of piglet birth weight, birth order, and litter size on subsequent growth performance, carcass quality, muscle composition, and eating quality of pork. J. Anim. Sci. 88:2767–2778. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. G., and Dunkin A. C.. . 1983. The effects of energy intake and dietary protein on nitrogen retention, growth performance, body composition and some aspects of energy metabolism of baby pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 49:221–230. doi: 10.1079/bjn19830029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwalibog A. 2006. Nutritive value and nutrient requirements [in Danish: Næringsværdi og næringsbehov]. 7th rev. ed.Denmark: Samfundslitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Coward W. A., Cole T. J., Gerber H., Roberts S. B., and Fleet I.. . 1982. Water turnover and the measurement of milk intake. Pflugers Arch. 393:344–347. doi: 10.1007/bf00581422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danfær A. C., and Strathe A. B.. . 2012. Quantitative and physiological aspects of pig growth. In: Knudsen K. E. B., Kjeldsen N. J., Poulsen H. D., and Jensen B. B., editors, Nutritional physiology of pigs. Online publication. Copenhagen (Denmark): SEGES Danish Pig Research Centre; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Devillers N., van Milgen J., Prunier A., and Le Dividich J.. . 2004. Estimation of colostrum intake in the neonatal pig. Anim. Sci. 78:305–313. doi: 10.1017/S1357729800054096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haggarty P., Franklin M. F., Fuller M. F., McGaw B. A., Milne E., Duncan G., Christie S. L., and Smith J. S.. . 1994. Validation of the doubly labeled water method in growing pigs. Am. J. Physiol. 267(6 pt 2):R1574–R1588. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.6.R1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggarty P., McGaw B. A., and Franklin M. F.. . 1988. Measurement of fractionated water loss and CO2 production using triply labelled water. J. Theor. Biol. 134:291–308. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(88)80060-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell R. J., Thomas M. J., and Boyd R. D.. . 1993. Limitations of sow milk yield on baby piglet growth. In: Proceedings of the Cornell Nutrition Conference for Feed Manufacturers; October 19 to 21 1993; Ithaca, NY; p. 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hojgaard C. K., Bruun T. S., Strathe A. V., Zerrahn J-E., and Hansen C. F.. . 2019a. High-yielding lactating sows maintained a high litter growth when fed reduced crude protein, crystalline amino acid-supplemented diets. Livest. Sci. 226:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2019.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hojgaard C. K., Bruun T. S., and Theil P. K.. . 2019b. Optimal crude protein in diets supplemented with crystalline amino acids fed to high-yielding lactating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 97:3399–3414. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojgaard C. K., Bruun T. S., and Theil P. K.. . 2019c. Optimal lysine in diets for high-yielding lactating sows1. J. Anim. Sci. 97:4268–4281. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Kristensen N. B., Che L., Wu D., and Theil P. K.. . 2020. Net absorption and liver metabolism of amino acids and heat production of portal-drained viscera and liver in multiparous sows during transition and lactation. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0417-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H. E. 1973. Grisenes vækst og udvikling i den præ- og postnatale periode, specielt med henblik på deres senere vækst og slagtekroppens sammensætning. rev. ed. Ikommission hos Landhusholdningsselskabet. [Google Scholar]

- Noble M. S., Rodriguez-Zas S., Cook J. B., Bleck G. T., Hurley W. L., and Wheeler M. B.. . 2002. Lactational performance of first-parity transgenic gilts expressing bovine alpha-lactalbumin in their milk. J. Anim. Sci. 80:1090–1096. doi: 10.2527/2002.8041090x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblet J., and Etienne M.. . 1987. Body composition, metabolic rate and utilization of milk nutrients in suckling piglets. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 27:829–839. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19870609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorelli G., Neil M., and Wigren I.. . 2009. Body composition and muscle glycogen contents of piglets of sows fed diets differing in fatty acids profile and contents. Livest. Sci. 123:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2008.11.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen T. F., Chang C. Y., Trottier N. L., Bruun T. S., and Theil P. K.. . 2019. Effect of dietary protein intake on energy utilization and feed efficiency of lactating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 97:779–793. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen H. D. 1995. Zinc oxide for weanling piglets. Acta Agric. Scand.A Anim. Sci. 45:159–167. doi: 10.1080/09064709509415847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozeboom D. W., Pettigrew J. E., Moser R. L., Cornelius S. G., and el Kandelgy S. M.. . 1994. In vivo estimation of body composition of mature gilts using live weight, backfat thickness, and deuterium oxide. J. Anim. Sci. 72:355–366. doi: 10.2527/1994.722355x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman J. R. 1997. Doubly Labelled Water: Theory and Practice. Rev. ed. London (UK): Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- Strathe A. V., Bruun T. S., Geertsen N., Zerrahn J-E., and Hansen C. F.. . 2017. Increased dietary protein levels during lactation improved sow and litter performance. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 232:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.08.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Danish Ministry of Justice 1995. Animal testing act, consolidation act no. 726 of September 9, 1993 (as amended by act no. 1081 of December 20, 1995). The Danish Ministry of Justice, Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Theil P. K., and Jørgensen H.. . 2016. Fat, energy, and nitrogen retention of artificially reared piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 94:320–323. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Theil P. K., Nielsen T. T., Kristensen N. B., Labouriau R., Danielsen V., Lauridsen C., and Jakobsen K.. . 2002. Estimation of milk production in lactating sows by determination of deuterated water turnover in three piglets per litter. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 52:221–232. doi: 10.1080/090647002762381104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore C. T., and Morgan C. A.. . 1990. Model components for the determination of energy and protein requirements for breeding sows: a review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 26:1–37. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(90)90053-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. H. 1995. Sows’ milk as a major nutrient source before weaning. In: Hennessy D. P., and Cranwell P. D., editors, Manipulating Pig Production V: Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Conference of the Australasian Pig Science Association. November 26 to 29, 1995; Canberra, Australia; p. 107–113. [Google Scholar]