Abstract

Objectives

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) may occur after acute metformin overdose, or from therapeutic use in patients with renal compromise. The mortality is high, historically 50% and more recently 25%. In many disease states, lactate concentration is strongly associated with mortality. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate the utility of pH and lactate concentration in predicting mortality in patients with MALA.

Methods

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science from their inception to April 2019 for case reports, case series, prospective, and retrospective studies investigating mortality in patients with MALA. Cases and studies were reviewed by all authors and included if they reported data on pH, lactate, and outcome. Where necessary, authors of studies were contacted for patient-level data. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for pH and lactate for predicting mortality in patients with MALA.

Results

Forty-four studies were included encompassing 170 cases of MALA with median age of 68.5 years old. Median pH and lactate were 7.02 mmol/L and 14.45 mmol/L, respectively. Overall mortality was 36.2% (95% CI 29.6–43.94). Neither lactate nor pH was a good predictor of mortality among patients with MALA. The area under the ROC curve for lactate and pH were 0.59 (0.51–0.68) and 0.43 (0.34–0.52), respectively.

Conclusion

Our review found higher mortality from MALA than seen in recent studies. This may be due to variation in standard medical practice both geographically and across the study interval, sample size, misidentification of MALA for another disease process and vice versa, confounding by selection and reporting biases, and treatment intensity (e.g., hemodialysis) influenced by degree of pH and lactate derangement. The ROC curves showed poor predictive power of either lactate or pH for mortality in MALA. With the exception of patients with acute metformin overdose, patients with MALA usually have coexisting precipitating illnesses such as sepsis or renal failure, though lactate from MALA is generally higher than would be considered survivable for those disease states on their own. It is possible that mortality is more related to that coexisting illness than MALA itself, and many patients die with MALA rather than from MALA. Additional work looking solely at MALA in healthy patients with acute metformin overdose may show a closer relationship between lactate, pH, and mortality.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13181-019-00755-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Metformin, Lactate, Survival, Mortality, Lactic acidosis

Introduction

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is a disease state in which metformin contributes to dysregulation of pH and lactate production, most commonly during critical illness. Severe hyperlactatemia with metabolic acidosis also sometimes occurs after metformin overdose. Patients with this syndrome have high mortality; however, the relationship between the degree of acidosis and mortality is unclear. We use a systematic review and meta-analysis approach to investigate the prognostic relationship between lactate concentration, pH, and death in MALA.

As a normal component of glucose homeostasis, hepatocytes take up circulating lactate and perform gluconeogenesis via the Cori cycle. Metformin inhibits this process. In therapeutic doses, metformin inhibits complex I in the electron transport chain, increasing cellular NADH and thereby inhibiting gluconeogenesis and contributing to euglycemia. In overdose, this leads to excessive lactate, both from inhibition of the electron transport chain and by preventing lactate clearance, because excess NADH prevents conversion to pyruvate. In addition, increased AMP from inhibition of complex I also inhibits gluconeogenesis [1]. During periods of critical illness, renal dysfunction induces toxic accumulation of metformin. Simultaneously, critical illness leads to elevated lactate production. As a result of the concomitant rise in lactate production and diminished clearance, hyperlactatemia ensues. Toxic accumulation of metformin can occur in the absence of renal failure when an otherwise healthy patient takes an overdose of metformin and can lead to similar metabolic derangement [1, 2].

Metformin is of the biguanide family of anti-hyperglycemic medications and has an approximately one-twentieth rate of metabolic acidosis with hyperlactatemia than its historical predecessor, phenformin. The epidemiological decline in the incidence of this disease state, though fortunate, limits physician experience and available clinical data. Given the relative rarity of MALA, current evidence poorly characterizes prognostic features and provides little augmentation of clinical decision making.

To date, MALA has been characterized and managed largely based on physician experience, presumed understanding of pathophysiology, and case report level evidence. An epidemiological incidence study from the Cochrane group in 2010 [2] found no increased risk of developing MALA in a healthy cohort on therapeutic doses of metformin, and a 2009 systematic review of metformin overdose found no deaths in patients with nadir serum pH greater than 6.9 or peak serum lactate concentrations less than 25 mmol/L [3]. No current paper explores prognostic features of MALA in a population of sick patients or patients with metformin overdose. This paper attempts to pool data from all available literature in order to better characterize the meaning of pH in the setting of MALA.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol for this systematic review is registered in the PROSPERO database with registration number CRD42018094253. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science from their inception to April 2019 for case reports, case series, prospective, and retrospective studies investigating mortality in patients with MALA. Studies were included if patients were diagnosed with MALA, and there was reported data on initial pH, initial lactate concentration, and mortality. Studies that did not report patient-level data and case reports on possible MALA after a major procedure were excluded. (See appendix-A for search strategy.)

Data Analysis

Interval data were reported as medians with interquartile ranges at 25% and 75% (IQR 25%, 75%). Frequency data were reported as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (95%, CI). Group comparisons were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U, alpha = 0.05, all with 2-tail. Receiver operating characteristic curves were tested against mortality, with area under the curve (AUC) (95%, CI) [4].

Results

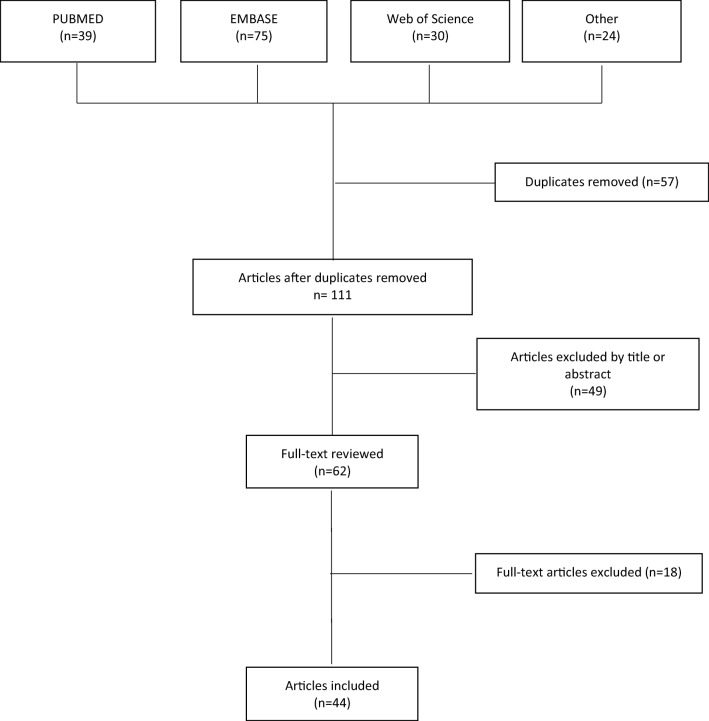

We found 108 citations in the combined Pubmed, Embase, and Web of Science search. Upon literature review, we found an additional 24 articles. Forty four [5–48] studies were included in this review. (See Fig. 1 for the study selection process.) Thirty-two studies were case reports, 6 were case series, 5 were retrospective, and 1 was a prospective study, Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Description of included studies.

| Author | Study type | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Ahmad (2002) [5] | Case report | 1 |

| Al-Jebawi (1998) [6] | Case report | 1 |

| Barbare (1981) [7] | Case report | 1 |

| Beaudot (1980) [8] | Case report | 1 |

| Bein (2013) [9] | Case report | 1 |

| Bergman (2015) [10] | Case report | 1 |

| Bethlehem, 2015 | Retrospective single center | 10 |

| Bruijstens (2008) [12] | Case series | 3 |

| Chudgar (2010) [13] | Case report | 1 |

| Dell’Aglio (2010) [14] | Case report | 1 |

| Falco (2013) [15] | Case series | 10 |

| Franzetti (1997) [16] | Case report | 1 |

| Friesecke (2010) [17] | Case series | 10 |

| Garg (2016) [18] | Case report | 1 |

| Goonoo (2017) [19] | Case report | 1 |

| Gowardman (1995) [20] | Case report | 1 |

| Guo (2006) [21] | Case series | 2 |

| Hayat JC (1974) [22] | Case report | 1 |

| Huang (2016) [23] | Retrospective single center | 11 |

| Hutchison (1987) [24] | Case report | 1 |

| Kavalci (2010) [2010] | Case report | 1 |

| Keller (2011) [26] | Retrospective single center | 6 |

| Khan (1993) [27] | Case report | 1 |

| Korhonen (1979) [28] | Case report | 1 |

| Kovacs (1996) [29] | Case report | 1 |

| Lacroix (1988) [30] | Case report | 1 |

| Laforest (2013) [31] | Case report | 1 |

| Lalau (1995) [32] | Prospective single center | 14 |

| Lalau (1999) [33] | Retrospective multi center | 49 |

| Leonaviciute (2018) [34] | Case report | 1 |

| Mercker (1997) [1997] | Case report | 1 |

| Mirouze (1974) [36] | Case series | 2 |

| Mizzi (2009) [37] | Case report | 1 |

| Pearlman (1996) [38] | Case report | 1 |

| Perrone (2011) [39] | Case series | 3 |

| Sadafi (1996) [40] | Case report | 1 |

| Schmidt (1997) [41] | Case report | 1 |

| Schure (2003) [42] | Case report | 1 |

| Timbrell (2012) [43] | Case report | 1 |

| Turkcuer (2009) [44] | Case report | 1 |

| Tymms (1988) [45] | Case report | 1 |

| Van Berlo-van de Laar (2011) [46] | Retrospective single center | 16 |

| Zandijk (1997) [47] | Case report | 1 |

| Zulqarnain (2014) [48] | Case report | 1 |

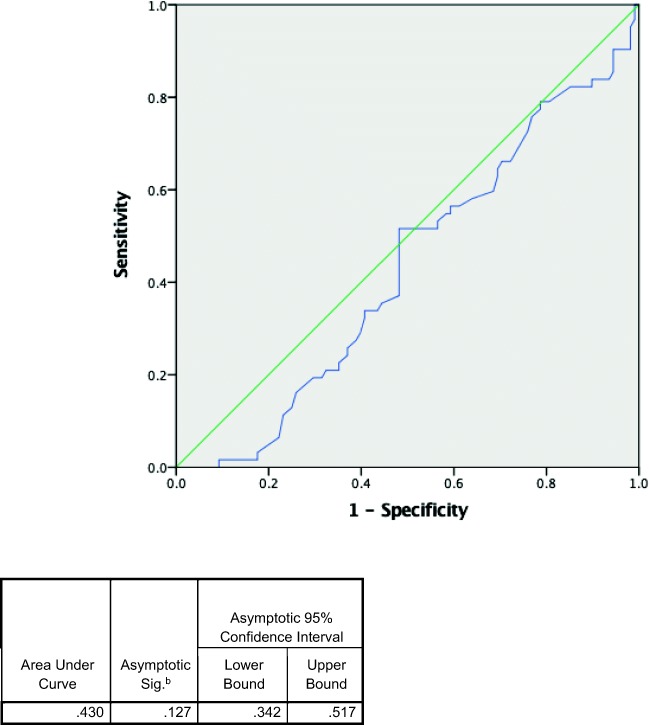

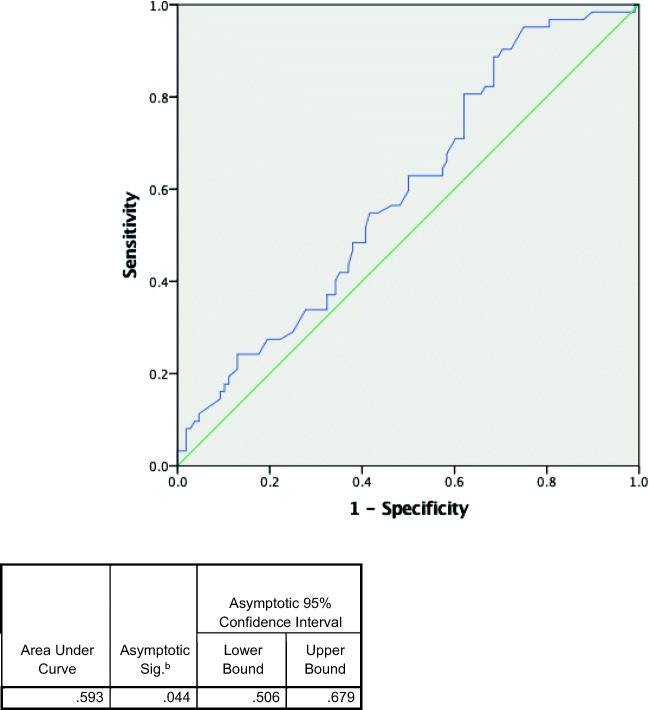

Across 44 included studies, 170 patients were included in the analysis. A total of 51% (IQR 43.1–58.0) of patients were female. The median age was 68.5 years old (IQR 60.0, 75.0). Median pH was 7.02 (IQR 6.86, 7.20), and median lactate was 14.45 mmol/L (IQR 10.15, 20.0). Overall mortality was 36.2% (95% CI 29.6–43.94). (See Table 2 for a summary of findings.) Table 3 compares the characteristics of survivors versus deceased. Patients who survived were significantly younger compared with those who are deceased, 67 versus 72 years old. Patients’ sex was similar in both groups. While median pH was the same in both survivor and nonsurvivor groups (7.02 and 7.03, respectively, p value 0.127), the median lactate was higher in the nonsurvivor group (15.40 versus 13.75, p value < 0.05. Neither pH nor lactate was a good predictor of mortality based on the ROC curve (Figs. 2 and 3) with AUC of 0.430 and 0.593, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients.

| Pooled sample size (n = 170) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 68.5 (60.0, 75.0) |

| Gender (% f)* | 51 (43.1–58.0) |

| pH (units)* | 7.02 (6.86, 7.20) |

| Lactate (mmol/L)* | 14.45 (10.15, 20.0) |

| Mortality (%)** | 36.5% (29.6–43.9) |

*Median (IQR 25%, 75%)

**Rate (95%, CI)

Table 3.

Patient characteristics, survivors versus nonsurvivors.

| Survivors | Non-survivors | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 108 | 62 | |

| Age (years)* | 67 (59.25, 72.00) | 72 (60.00, 79.00) | 0.046** |

| Gender (% f) | 50 (40.7–59.3) | 52 (39.5–63.6) | 0.874*** |

| pH (units)* | 7.02 (6.87, 7.22) | 7.03 (6.86, 7.14) | 0.127*** |

| Lactate (mmol/L)* | 13.75 (8.94, 19.78) | 15.40 (11.95, 22.62) | 0.044** |

*Median (IQR 25%, 75%)

**p < 0.05 statistically significant

***Not significant

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of pH predicting mortality.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of lactate predicting mortality.

Discussion

Based on our meta-analysis of the available studies, the degree of lactate elevation and metabolic acidosis are poor predictors of mortality in MALA. The derangements in pH and lactate seen in MALA appear to have an associative rather than a predictive relationship to mortality. Given that hyperlactatemia with metabolic acidosis is the sine qua non of MALA itself, these laboratory findings do prognosticate the significant mortality rate observed in MALA. However, degree of deviation from normal in these values do not have an expected dose-response relationship. Therefore it appears that mortality linked to MALA is not caused by changes in pH and lactate.

We used a thorough literature search strategy spanning three databases to minimize selection bias and identified 44 publications including 170 cases of MALA. Where patient data were unavailable, we contacted authors directly to maximize inclusion of patients. Quality of data was low to moderate, comprising case series, case reports, and retrospective data. Measurement bias is negligible since the outcome of interest, mortality, is a hard endpoint, and variables were numerical laboratory measurements.

Potential confounders to our study include selective reporting, misidentification of MALA for another disease process and vice versa, variation in standard medical practice both geographically and across the study interval, and sample size. Additionally, it is possible that patients with extremes of lactate elevation or metabolic acidosis were regarded as sicker than other patients. They might then receive more prompt and thorough diagnostic evaluation and more aggressive treatment such as prolonged or expedited hemodialysis. Since 2015, EXTRIP guidelines for hemodialysis in MALA explicitly base some treatment recommendations on pH and lactate [49], so cases reported since then are especially prone to this bias. The best predictor of mortality may in fact be whether or not the patient receives aggressive treatment.

Implications for clinical practice include that the diagnosis of MALA predicts a mortality of about 36% regardless of pH and lactate. Though it may be counterintuitive, laboratory values closer to the normal range should not be interpreted as reassuring, and seemingly marked pH or lactate disturbance may not be more predictive of death than the diagnosis of MALA itself. Indeed, the numeric values of pH and lactate appear only as useful in prognosticating mortality as they are in establishing the diagnosis of MALA.

Implications for research may be drawn from our study as well. Though this systematic review and meta-analysis was unable to demonstrate a predictive correlation between pH or lactate concentration and mortality in MALA, it is possible that including a larger sample size or performing a prospective study with protocolized treatment may reveal such a relationship. Additionally, the apparent dissociation between pH, lactate, and mortality in MALA leads to the questions of fundamental disease mechanism and potential therapeutic targets.

Conclusion

Despite limitations to our study, we conclude there is no data to support the degree of pH or lactate disturbance as prognostic in patients diagnosed with MALA. The receiver operating curves showed poor predictive power of pH and lactate for mortality in MALA. The implications for clinical practice and future research are important, since the derangements in pH and lactate seen in MALA appear to have an associative rather than a predictive relationship to mortality.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 6 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Christopher Stewart, senior librarian at State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, for his help in formulating the literature search strategy as well as Mr. Rasheed Bailey for the assistance in collecting the data.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Sources of Funding

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Viollet B, Guigas B, Garcia N, Leclerc J, Foretz M, Andreelli F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci. 2012;122:253–270. doi: 10.1042/CS20110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD002967. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dell’Aglio DM, Perino LJ, Kazzi Z, Abramson J, Schwartz MD, Morgan BW. Acute metformin overdose: examining serum pH, lactate level, and metformin concentrations in survivors versus nonsurvivors: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(6):818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IBM Corp. Released . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad S, Beckett M. Recovery from ph 6.38: lactic acidosis complicated by hypothermia. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:169–171. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Jebawi AF, Lassman MN, Abourizk NN. Lactic acidosis with therapeutic metformin blood level in a low-risk diabetic patient. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(8):1364–1365. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbare JC, Grippon P, Ricome JL, Auzepy P. Metformin associated lactic acidosis. Sem Hôpitaux Paris. 1981;57:586–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaudot C, Merceron RE, Lavieuville M, Noel M, Brohon J, Raymond JP. Reversible lactic acidosis in a diabetic on high dose metformin. Diabetes Metab. 1980;6:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bein C, Duroy E, Valette S, Gaiffe A, Davani S. Metformin self poisoning: a case report. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2013;27:76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman M, Filopei J, Ramesh N, Thomas S. Refractory shock in a diabetic - toxic situation with an antidote. Chest. 2015;148(4):372A. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrario M, Apicella A, Della Morte M, Beretta E. A case of severe metformin-associated lactic acidosis treated with CVVHDF and regional anticoagulation with sodium citrate. G Ital Nefrol. 2018;35(5):2018-vol5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruijstens LA, van Luin M, Buscher-Jungerhans PM, Bosch FH. Reality of severe metformin-induced lactic acidosis in the absence of chronic renal impairment. Neth J Med. 2008;66(5):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chudgar S, Schell J. When good drugs go bad. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine, Washington, D.C. Abstract 236. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2010;5(suppl 1).

- 14.Dell’Aglio DM, Perino LJ, Todino JD, Algren DA, Morgan BW. Metformin overdose with a resultant serum pH of 6.59: survival without sequalae. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(1):e77–e80. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falco VD, Milano A, Battilana M, et al. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: risk factors and prognostic factors. Crit Care. 2013;17(Suppl 2):P453. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franzetti I, Paolo D, Marco G, Emanuela M, Elisabetta Z, Renato U. Possible synergistic effect of metformin and enalapril on the development of hyperkaliemic lactic acidosis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1997;38:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friesecke S, Abel P, Roser M, Felix SB, Runge S. Outcome of severe lactic acidosis associated with metformin accumulation. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R226. doi: 10.1186/cc9376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg SK, Singh O, Deepak D, Singh A, Yadav R, Vashist K. Extracorporeal treatment with high-volume continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration and charcoal-based sorbent hemoperfusion for severe metformin-associated lactic acidosis. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20(5):295–298. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.182205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goono MS, Creagh FM, Gandhi R, Tran P. Successful treatment of a case of metformin-associated lactic acidosis caused by metformin overdose. Diabet Med. 2017;34(suppl. S1):36–194. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gowardman JR, Havill J. Fatal metformin induced lactic acidosis: case report. N Z Med J. 1995;108:230–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo PY, Storsley LJ, Finkle SN. Severe lactic acidosis treated with prolonged hemodialysis: recovery after massive overdoses of metformin. Semin Dial. 2006;19(1):80–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayat JC. The treatment of lactic acidosis in the diabetic patient by peritoneal dialysis using sodium acetate. A report of two cases. Diabetologia. 1974;10:485–487. doi: 10.1007/BF01221643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Castelino RL, Peterson GM. Lactic acidosis and the relationship with metformin usage: case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(46):e4998. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutchison SMW, Catterall JR. Metformin and lactic acidosis –a reminder. Br J Clin Prac. 1987;41:673–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavalcı C, Güldiken S, Taşkıran B, Kavalcı G. Fatal lactic acidosis due to metformin. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;9:112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller G, Cour M, Hernu R, Illinger J, Robert D, Argaud L. Management of metformin-associated lactic acidosis by continuous renal replacement therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan IH, Catto GR, MacLeod AM. Severe lactic acidosis in patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. BMJ. 1993;307:1056–1057. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6911.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korhonen T, Idanpaan-Heikkila J, Aro A. Biguanide-induced lactic acidosis in Finland. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15:407–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00561739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs KA, Morton AR. Metformin associated lactic acidosis. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;3:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacroix C, Hermelin A, Gerson M, Nouveau J, Guiberteau R. Lactic acidosis caused by metformin. Value of intraerythrocyte levels. Presse Med. 1988;17:1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laforest C, Saint-Marcoux F, Amiel JB, Pichon N, Merle L. Monitoring of metformin-induced lactic acidosis in a diabetic patient with acute kidney failure and effect of hemodialysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(2):147–151. doi: 10.5414/CP201728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalau JD, Lacroix C, Compagnon P, de Cagny B, Rigaud JP, Bleichner G, Chauveau P, Dulbecco P, Guérin C, Haegy JM, et al. Role of metformin accumulation in metformin-associated lactic acidosis. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(6):779–784. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. Prognostic value of arterial lactate levels and plasma metformin concentrations. Drug Saf. 1999;20(4):377–384. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leonaviciute D, Madsen B, Schmedes A, Buus NH, Rasmussen BS. Severe metformin poisoning successfully treated with simultaneous venovenous hemofiltration and prolonged intermittent hemodialysis. Case Rep Crit Care. 2018;2018:3868051. doi: 10.1155/2018/3868051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercker SK, Maier C, Neumann G, Wulf H. Lactic acidosis as a serious perioperative complication of antidiabetic biguanide medication with metformin. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1003–1005. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirouze J, Mion C, Beraud JJ, Selam JL. Lactic acidosis during renal insufficiency in two diabetic patients treated with metformin. Nouv Press Med. 1976;5:1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizzi A, Landoni G, Corno L, Fichera M, Nuzzi M, Zangrillo A. How to explain a PaO2 of 140 mmHg in a venous line? Acta Biomed. 2009;80(3):262–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearlman BL, Fenves AZ, Emmett M. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis. Am J Med. 1996;101:109–110. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrone J, Phillips C, Gaieski D. Occult metformin toxicity in three patients with profound lactic acidosis. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(3):271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Safadi R, Dranitzki-Elhalel M, Popovtzer M, Ben-Yehuda A. Metformin-induced lactic acidosis associated with acute renal failure. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16:520–522. doi: 10.1159/000169052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt R, Horn E, Richards J, Stamatakis M. Survival after metformin-associated lactic acidosis in peritoneal dialysis–dependent renal failure. Am J Med. 1997;102:486–488. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schure PJ, de Gooijer A, van Zanten AR. Unexpected survival from severe metformin-associated lactic acidosis. Neth J Med. 2003;61(10):331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timbrell S, Wilbourn G, Harper J, Liddle A. Lactic acidosis secondary to metformin overdose: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:230. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turkcuera I, Erdura B, Sarib I, Yuksela A, Turaa P, Yuksela S. Severe metformin intoxication treated with prolonged haemodialyses and plasma exchange. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16:11–13. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32830a7567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tymms DJ, Leatherdale BA. Lactic acidosis due to metformin therapy in a low risk patient. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:230–231. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.64.749.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Berlo-van de Laar IRF, Vermeij CG, Doorenbos CJ. Metformin associated lactic acidosis: incidence and clinical correlation with metformin serum concentration measurements. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36:376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zandijk E, Demey HE, Bossaert LL. Metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 1997;53:543–546. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zulqarnain MA, Ahmed A, Ahmed W, Chakka A, Bhargava P. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A6191. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calello D, Liu KD, Wiegand TJ, Roberts DM, Lavergne V, Gosselin S, Hoffman RS, Nolin TD, Ghannoum M, EXTRIP Workgroup Extracorporeal treatment for metformin poisoning: systematic review and recommendations from the extracorporeal treatments in poisoning workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1716–1730. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 6 kb)