Abstract

Introduction

Survival for colorectal cancer is improved by earlier detection. Rapid assessment and diagnostic demand have created a surge in two-week rule referrals and have subsequently placed a greater burden on endoscopy services. Between 2009 and 2014, a mean of 709 patients annually were referred to Royal Surrey County Hospital with a detection rate of 53 cancers per year giving a positive predictive value for these patients of 7.5%. We aimed to assess what impact the 2015 changes in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence referral criteria had on local cancer detection rate and endoscopy services.

Methods

A prospectively maintained database of patients referred under the two-week rule pathway for April 2017–2018 was sub-analysed and the data cross-referenced with all diagnostic reports.

Findings

There were 1,414 referrals, which is double the number of previous years; 80.6% underwent endoscopy as primary investigation and 62 cancers were identified, 51 being of colorectal and anal origin (positive predictive value 3.6%). A total of 88 patients were diagnosed, with other significant colorectal disease defined as high-risk adenomas, colitis and benign ulcers. Overall, a total of 10.6% of our two-week rule patients had a significant finding.

Since the 2015 referral criteria, despite a dramatic rise in two-week rule referrals, there has been no increase in cancer detection. It has placed significant pressure on diagnostic services. This highlights the need for a less invasive, cheaper yet sensitive test to rule out cancer such as faecal immunochemical testing that can enable clinicians to triage and reduce referral to endoscopy in symptomatic patients.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Early detection, Occult blood

Introduction

In the UK, there are an estimated 41,700 new cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed each year. It is the fourth most common cancer after prostate, breast and lung cancers.1 Mortality from cancer is mostly determined by the stage and patient age at diagnosis.2 Ninety per cent of patients who are diagnosed with stage I colorectal cancer will survive at least five years compared with 10% of those diagnosed with stage IV disease.3 It is therefore important that a standardised pathway exists, coupled with availability of diagnostic resources to enable prompt diagnosis. This is currently determined by the two-week rule pathway set out by the guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Those with red flags from primary care such as changes in bowel habit, abdominal pain, weight loss or anaemia are referred to colorectal specialists in local trusts.4 The pathway requires that patients are seen in specialist clinics or arrangements are made for definitive investigation within two weeks of referral.

Nationally, the two-week rule pathway has been met with controversy. In the earlier years, it was infrequently used and guidelines were poorly adhered to.5 The National Audit Office in 2010 reported a four-fold variation across primary care trusts for referral rates.6 More recently, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of referrals and subsequent need for endoscopy. Of all referrals, only 3–4% will end up with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, and only 27% of all colorectal cancers are picked up from these referrals nationally.7,8 In June 2015, the NICE guideline criteria for referral were changed. This may be the biggest contributor to the increased rate. One of the key alterations was to include patients that are over 60 with ‘changes in bowel habit’ alone. Prior to this, referral criteria mandated the necessity for the change in bowel habit to have lasted six weeks or more and comprise increased frequency or looser stools.4 This means that eligible patients now includes those that may have a transient gastrointestinal infection or constipation, which is rarely a symptom of bowel cancer. Selvachandran et al demonstrated that 4.2% of those with bowel cancer had symptoms of constipation compared with 69.5% having increased frequency of motions.9

Almost all patients referred under the two-week rule pathway will require investigations and the majority undergo endoscopy. Colonoscopy is seen as the gold standard approach to rule out colorectal cancer. Computed tomography colonography is also widely used. Both modes require bowel preparation. This is inconvenient for patients and carries risk, particularly to the frail and may cause electrolyte disturbance and renal disorders.10 Colonoscopy itself can be unpleasant and painful. There is also a small risk of perforation (up to 1 in 500), the consequences of which can be very serious.11

The number of endoscopy cases occurring per year in the UK is expected to increase from 1.7 million in 2015 to over 2.4 million in 2020.12 A diagnostic colonoscopy costs £37213 and therefore such a rise will cost the NHS approximately £250 million extra each year. Furthermore, current workforce availability means this rise would be unsustainable.

In the Royal Surrey County Hospital, we keep a prospectively maintained database of two-week rule patients. Between January 2009 and December 2014, a mean of 709 patients annually were referred to Royal Surrey County Hospital with a detection rate of 53 colorectal cancers per year giving a positive predictive value (PPV) of 7.5%. The average referral rate to endoscopy of two-week rule patients was 75.5%. The aim of this study was to elucidate the impact of the rising number of two-week rule patients. We assess how the recent changes in NICE referral criteria from mid-2015 have affected local colorectal cancer detection rate and endoscopy services.

Methods

A prospectively maintained database of patients referred under the two-week rule pathway has been maintained at the Royal Surrey County Hospital since 2009. The financial year April 2017–2018 was sub-analysed and compared with results previously collated for the period January 2009 to December 2014. Criteria assessed include clinic appointment outcomes, endoscopic outcomes and radiological reports.

Findings

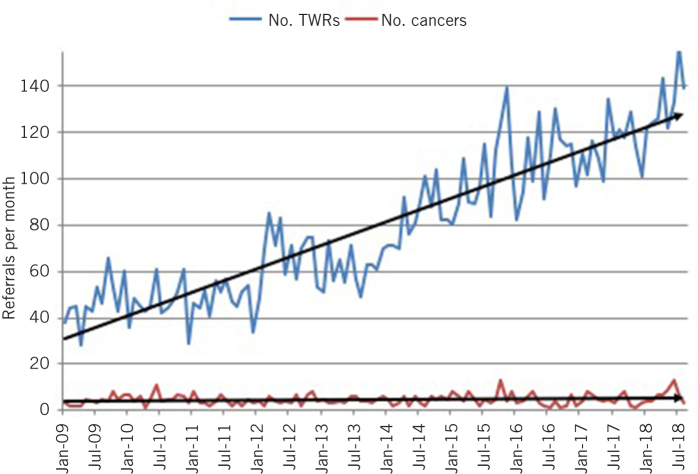

There were 1,414 two-week rule referrals between April 2017 and April 2018. This is double the number compared with the mean in the years 2009–2014 (Fig 1). Of 1,414 referrals, 62 cancers were identified; 51 were of colorectal and anal origin. The PPV for bowel cancer had therefore reduced by half from 7.5% to 3.6% (95% confidence interval, CI, 2.88–4.72, p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

The increased referral rate of patients (upper line) compared with the static diagnoses of bowel cancer (lower line) among these patients from January 2009 to July 2018.

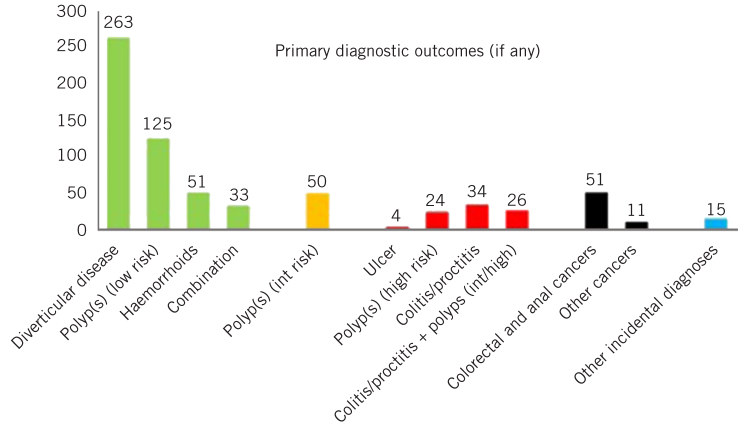

Of the 1,414 patients, 1,140 (80.6%) had onward referral for primary endoscopy. Of all patients who underwent endoscopy, there were two bowel perforations which resulted in laparotomy, and both required stoma formation. In 727 patients, a cause of their symptoms was not identified and they had no diagnosis. Eighty-eight patients were found to have significant colorectal disease other than colorectal cancer, classified as high-risk adenomas, colitis and benign ulcers (Fig 2). Polyp risk was categorised to low, intermediate or high as per colonoscopy surveillance recommendations by Atkin et al.14 Overall, PPV for a significant colorectal diagnosis or any form of cancer was 10.6%.

Figure 2.

The diagnoses found, if any, given from all investigations; 727 patients (51.4%) received no diagnosis. The darker bars signify cancers or other significant colorectal diagnoses.

Discussion

We sub-analysed a year of two-week rule colorectal pathway patients and have compared the data with previous years. This demonstrated an increasing trend in the number of these referrals, probably created by easier inclusion criteria from the NICE guidelines.

Despite a doubling in the number of referrals, no extra bowel cancers were detected. The extra demand has created a change in clinic availability and delays other patients from seeing a specialist via the normal avenue of referrals. In turn, the endoscopy unit is more heavily burdened by the demand of the onward referrals. This is of minimal apparent benefit and could potentially delay routine endoscopies. Life-changing complications occurred for two patients, who required laparotomies and stoma formation due to direct iatrogenic injury from colonoscopy. Neither of these patients had bowel cancer as a cause for their symptoms.

A potential benefit to performing more colonoscopies is that a greater number of polypectomies are performed. Some of these polyps may have developed into cancers at a later stage, but it is unlikely that they were implicated in any of the presenting symptoms. A systematic review by Heitman et al demonstrated that the prevalence in an asymptomatic average risk population of advanced adenomas (polyps of more than 1cm) to be 5.7%.15 The prevalence among our population was 7.1%, which could be seen as a negligible increase. The benefit, therefore, of performing this number of colonoscopies resulting in polypectomies in two-week rule patients remains to be seen.

Use of faecal occult blood investigations?

Faecal occult blood testing is offered as a screening tool for those aged 60–74 years inclusive in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Scotland is 50–74 years inclusive. The presence of blood in faeces can indicate colorectal cancer and a colonoscopy is recommended. The traditional guaiac-based testing is replaced by faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) across the UK. This form of testing is more sensitive for cancer and the quantitative result that it supplies can be correlated to severity of neoplasia, as well as picking up other significant colorectal disease.16 In screening programmes, high thresholds are being used as the basis for referral dependent on the endoscopy capacity available (England 120mg/g, Scotland 80mg/g, Wales 150mg/g). At very low thresholds (< 10mg/g), FIT has a very high negative predicted value and it has therefore been advocated in its use as an investigation in symptomatic patients for triage and as a ‘rule out’ test both in primary care and secondary care.16–18

In 2015, the reviewed NICE guidance recommended the use of the faecal occult blood test in the low-risk group of patients (< 3% risk). While this did not specify which faecal occult blood test should be used at the time, only the guaiac test was routinely available, and most laboratories had stopped offering the test due to its poor diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. There was wide contention around this recommendation.19 In 2017, NICE published diagnostic guidelines that recommend the use of FIT for the detection of faecal occult blood in the clinical guideline criteria for a two-week rule referral.20 NICE recommends a threshold for two-week rule referral for a concentration of faeces 10 μg Hb/g or greater.20 They have not made any recommendations about FIT for patients once into secondary care or specifically once on the two-week rule pathway.

Studies are required to ascertain whether FIT can confidently downgrade patients from the two-week rule pathway. If this is possible, many patients could potentially avoid an invasive investigation. While ‘safety-netting’ these patients may have an adverse effect on clinic capacity, this will be heavily offset by the reduction of potential harm and costs by the reduction in the numbers of colonoscopies performed. The ‘NICE FIT study’ is a multicentre large-scale study in England that aims to address these questions about FIT in the symptomatic population and will offer data for both low and high-risk patient groups.21

A deterrent to FIT in the context of a symptomatic two-week rule patient is the time it takes for laboratory-based processing. This can impact on the 28-day diagnostic target as the result may take a few days and a further appointment is then required to inform the patient of the result and action it. There are point of care FIT analysers designed for professional use that can provide a result within a matter of minutes. They offer the potential for point of care FIT to be incorporated into a clinic setting. Little is known about these point of care devices and more studies are required to assess their diagnostic performance. The ‘POCFIT study’ is currently addressing this question at Royal Surrey County Hospital.

We believe that the most appropriate setting for FIT is in primary care. In this setting, all onward referrals can then be triaged at source in a more appropriate way. This in turn will reduce the rising number of two-week rule patients who do not warrant such urgent specialist review and diagnosis. From that, a sensible watch and wait approach for resolution of minor or more tolerable symptoms could be employed in patients with a negative FIT result.

The use of FIT as per the NICE diagnostic guidance is not universally employed. Indeed, the rollout of FIT in primary care trusts that refer to Royal Surrey County Hospital has only just commenced. The evidence presented here suggests that a large group of patients have not benefitted from colonoscopy. A suitable test to allay clinical concerns may have avoided hospital referral and ultimately a potentially dangerous investigation.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK . Bowel cancer statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero (cited January 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPhail S, Johnson S, Greenberg D. et al. Stage at diagnosis and early mortality from cancer in England. Br J Cancer 2015; : S108–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2014; : 1,490–1,502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Suspected Cancer: Recognition and Referral. NICE guideline NG12. London: NICE; 2025 (updated 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John SKP, Jones OM, Horseman N. et al. Inter general practice variability in use of referral guidelines for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2007; : 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Intelligence Network . Urgent GP Referral Rates for Suspected Cancer. London: NCRAS; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health England . Routes to Diagnosis 2015 Update: Colorectal Cancer. London: PHE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser CG. Faecal immunochemical tests (FIT) in the assessment of patients presenting with lower bowel symptoms: Concepts and challenges. Surgeon 2018; : 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvachandran SN, Hodder RJ, Ballal MS. et al. Prediction of colorectal cancer by a patient consultation questionnaire and scoring system: a prospective study. Lancet 2002; : 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Florentin M, Liamis G, Elisaf MS. Colonoscopy preparation-induced disorders in renal function and electrolytes. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; : 50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohsiriwat V. Colonoscopic perforation: Incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. World Journal of Gastroenterol 2010; : 425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham; Strategy Unit, NHS Midlands; Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit . Scoping the Future: An evaluation of endoscopy capacity across the NHS in England. London: Cancer Research UK; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westwood M, Ramos IC, Lang S. et al. Faecal immunochemical tests to triage patients with lower abdominal symptoms for suspected colorectal cancer referrals in primary care: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess 2017; : 1–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atki WS, Saunders BP. Surveillance guidelines after removal of colorectal adenomatous polyps. Gut 2002; : 6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heitman SJ, Ronksley PE, Hilsden RJ. et al. Prevalence of adenomas and colorectal cancer in average risk individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; : 1,272–1,278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Digby J, Fraser CG, Carey FA. et al. Faecal haemoglobin concentration is related to severity of colorectal neoplasia. J Clin Pathol 2013; : 415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westwood M, Lang S, Armstrong N. et al. Faecal immunochemical tests (FIT) can help to rule out colorectal cancer in patients presenting in primary care with lower abdominal symptoms: a systematic review conducted to inform new NICE DG30 diagnostic guidance. BMC Med 2017; : 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele RJC, Fraser CG. Faecal immunochemical tests (FIT) for haemoglobin for timely assessment of patients with symptoms of colorectal disease. In: Olsson L, ed. Timely Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International; 2018. . 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele R, Machesney M, Halloran SP. Use of faecal occult blood tests in symptomatic patients. BMJ 2015; : 4,256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Quantitative Faecal Immunochemical Tests to Guide Referral for Colorectal Cancer in Primary Care. Diagnostics Guidance DG30. London: NICE; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The NICE FIT Study . https://www.nicefitstudy.com (cited January 2020). [Google Scholar]