Abstract

Study Objectives:

Previous research has reported mixed results in terms of sex differences in sleep quality. We conducted an analysis of measurement invariance of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) between men and women to provide a necessary foundation for examining sleep differences.

Methods:

The sample included 861 adults (mean age = 52.73 years, 47.85% male) from the 2012–2016 wave of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) Refresher Biomarker survey. We randomly divided the sample into two half samples for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), respectively. We conducted EFA with a weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator and Geomin rotation to explore the underlying structure of the PSQI. We then employed multiple-group CFA with the WLSMV estimator and theta parameterization to examine measurement invariance between males and females.

Results:

EFA suggested a two-factor structure of the PSQI, and the two-factor CFA model fit the data well. The finding that the two-factor PSQI model was invariant between males and females on configuration, factor loadings, thresholds for all but one measure, and residual variances for all but one measure provided evidence that the two-factor PSQI model was partially invariant between men and women. Females had higher means on latent factors, suggesting worse self-reports of sleep among women.

Conclusions:

Overall, the measure of the PSQI assesses the same factors in a comparable way among men and women. Women reported worse sleep than men.

Citation:

Li L, Sheehan CM, Thompson MS. Measurement invariance and sleep quality differences between men and women in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(12):1769–1776.

Keywords: measurement invariance, midlife, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, sleep quality

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) has been widely used by researchers and clinicians to measure self-reported sleep quality and discrepant sex differences have been reported, but it remains unknown whether these sex differences may be artifacts of measurement model differences. This study examined the factorial structure of the PSQI and tested its measurement invariance and compared latent means between males and females.

Study Impact: This study provides evidence that comparisons by sex of self-reported sleep using the PSQI are valid. Importantly, by thorough evaluation of the measurement model, this study supports previous findings that women report worse sleep quality than men, which may help to understand the broader sex-based differences in health.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep is critical for mental and physical well-being.1–6 Developing ways to accurately and succinctly measure perceived sleep quality across the entire population is important for studying health broadly. However, this is complicated by the fact that there are mixed results in terms of sex differences in sleep: some examinations of sex differences in sleep report better sleep quality for men,5,7,8 some report better sleep quality for women,9 and yet others report mixed results.10,11 These divergent results could be due to differences in perception of sleep,11–13 biological differences,14,15 different sampling frames, different measures of sleep,10 or measurement issues.16 Here we aim to provide a greater understanding of how perception of sleep and sex-based measurement model differences may influence substantive conclusions regarding sex differences in sleep quality in a commonly used battery of sleep quality.

For almost three decades, researchers and clinicians have used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index17 (PSQI) to measure sleep quality because it measures multiple aspects of sleep and relies on self-reports rather than on trained personnel or intrusive and expensive equipment. Previous studies have shown the PSQI has strong internal and external validity across diverse samples.18 Worse self-reported sleep quality as measured by the PSQI has been linked to higher recurrence rates of depression,19 increased risk for physical disability,4 lower levels of well-being,6 and greater mortality risk.3 Objective measures of sleep such as those collected via polysomnography and actigraphy are more difficult and expensive to obtain but capture the physiological processes of sleep.20 Research suggests that a combination of self-reported and objective sleep measures has greater predictive power than a single measure.21 However, unlike objective sleep measures or their combination, self-reported sleep measures such as the PSQI are susceptible to measurement challenges.

A critical measurement challenge, especially when comparing groups in general, and men to women in particular on the PSQI, concerns measurement invariance of the PSQI. Measurement invariance or equivalence tests whether the latent construct is assessed in the same way across groups, samples, or time.22 For example, if the PSQI displays measurement equivalence by sex, it can be concluded that men and women perceive and interpret each measure of the PSQI similarly, such that men and women with equal levels of sleep quality have equal probabilities of having specific quality ratings on the sleep measures; thus, sex comparisons in the PSQI are valid. Otherwise, the latent construct of the PSQI is not comparable between men and women because it is assessed differently in men and women. However, despite these critical methodological implications and the fact that prior research has compared men and women on the PSQI,8,11,13,14 we are aware of no past work that has formally tested measurement invariance between men and women (there are exceptions for other population groups23,24).

The lack of an explicit examination of measurement invariance by sex in the PSQI is also notable given that there are reasons to anticipate there could be measurement differences between men and women. For example, women are much more likely to report specific sleep issues such as nightmares,25 insomnia,7 and sleep interruptions26 than men and sex-based measurement problems of the PSQI have been found for a Chinese sample.13 Specifically, among the Chinese sample more negative perceptions about aging in women than men were suggested to explain why women respond more negatively in reporting sleep quality.13 Men and women have also been shown to have different perceptions of sleep,11,12 which could alter how they respond to the PSQI. Additionally, recent research has found significant sex-based measurement noninvariance in other commonly utilized batteries such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale27 (which includes an item related to sleep) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.28 These findings are important because they not only suggest that there could be measurement errors with the PSQI, but also because these researchers argue that sex comparisons for these batteries may not be valid.27,28 That is, explicitly and formally testing for measurement invariance by sex is necessary to understanding sex differences in sleep quality, as previous research has indicated that failing to properly address measurement errors can lead to biased estimates29 and even distort substantive conclusions regarding sex differences.28 Indeed, clarifying measurement invariance could help to elucidate the discrepant sex differences in reports of sleep quality.7–9 In summary, it remains unclear whether there are measurement differences between men and women, as measured by the PSQI, which is critical for determining whether sex differences in sleep quality exist or are simply artifacts of measurement model differences.

In addition to measurement invariance, another measurement challenge of the PSQI that may complicate the understanding of sex differences in sleep concerns the factor structure. Researchers have found approximately 30 distinct factor structures for the PSQI that vary by sample and methodology.30 Some researchers have argued for a one-factor structure,17 and others have found support for various types of two-31–35 or three-factor30,36 structures. These results may be due to different approaches as prior researchers have utilized confirmatory factor analysis (CFA),32,33 exploratory factor analysis (EFA),35 and principle component analysis as techniques to explore underlying factors of the PSQI.31,35 Given that different factor structures can lead to different conceptual and substantive conclusions, here we examine alternative measurement models for men and women using EFA, and also test measurement invariance for CFA specifications noted in previous research.30

Overall, we aim to provide a comprehensive examination of the potential influence of differences in measurement models for substantive conclusions regarding sex differences in sleep quality across factor structure. We used data from American adults to better understand the measurement properties and factor structure of the PSQI, and how they vary across sex by employing both EFA and CFA techniques in separate samples. We evaluated the fit of the one-, two-, and three-factor structures of the PSQI and then tested for measurement invariance and differences in latent means of sleep quality between adult men and women.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in this study were from the 2012–2016 Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) Refresher Biomarker study.37 MIDUS is a longitudinal, nationally representative survey that investigates the roles of biomedical, psychological, and social factors in mental and physical health in adults. Detailed information regarding MIDUS and its representativeness has been published elsewhere.38 During 2011–2014, the MIDUS Refresher study was conducted on 3,577 adults aged between 25 and 74 years. An additional sample of 508 Milwaukee African-American adults, aged between 25 and 64 years, was also recruited in 2012–2013 for the MIDUS Refresher survey. Participants of the MIDUS Refresher survey were eligible for biomarker data collection during 2012–2016. Because the PSQI was only included in the biomarker data collection, we used the refresher biomarker survey and excluded two adults who had missing data on all items of the PSQI, such that the final sample comprised 861 adults (412 males and 449 females) ranging in age between 26 and 78 years, with an average age of 52.73 years (standard deviation [SD] = 13.45). An independent sample t test showed that males were slightly older than females (males: mean [SD] 54.26 [14.03] years; females: 51.32 [12.76] years; t859 = 3.21, P = .001). Approximately 70% of participants (77% of males and 64% of females) in the sample were white, and about 52% (54% of males and 51% of females) had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Males were more likely to be white than females (χ21 = 19.64, P < .001), which is likely due to the oversampling of African-American respondents. Males and females were comparable in education (χ21 = 0.55, P = .46).

Measures

Participants self-reported sleep during the past month using the 19 items of the PSQI.17 The self-reported items consist of 15 four-point items (eg, 0 = not during the past month, 3 = three or more times a week) and 4 open-ended items. The open-ended items are also scored as constructed categorical values ranging from 0 to 3. Consistent with the scoring guidelines,17 the 19 self-reported items are combined into 7 clinically relevant domains of sleep difficulties, each component scores from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating worse sleep (for more detailed information regarding the scoring of the PSQI see https://www.sleep.pitt.edu/instruments/). These components are (1) self-reported sleep quality (one item; ie, “how would you rate your sleep quality overall?”), (2) sleep latency (two items; eg, “how often have you had trouble sleeping because you could not get to sleep within 30 minutes?”), (3) sleep duration (one item; ie, “how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night?”), (4) habitual sleep efficiency (three items; eg, “when have you usually gone to bed at night?”), (5) sleep disturbances (nine items; eg, “how often have you had trouble sleeping because you woke up in the middle of the night or early morning?”), (6) use of sleeping medication (one item; ie, “how often have you taken medicine to help you sleep?”), and (7) daytime dysfunction (two items; eg, “how often have you had trouble staying awake while driving, eating meals, or engaging in social activity?”).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses for the seven components of the PSQI were calculated using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, United States). The full sample was randomly split into two independent subsamples, one used for EFA (n1 = 429) and another for CFA (n2 = 432). Independent sample t tests or Pearson chi-square tests showed that the two samples were statistically indistinguishable on demographic variables (ie, age, sex, race, education, household income, and marital status) and scores of seven components of the PSQI. Because previous studies suggested that the PSQI has one, two, or three correlated factors,30,39 we conducted EFAs for one-, two-, and three-factor solutions in Mplus 7.040 using categorical variable methodology to accommodate the ordinally-scaled indicators by employing weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation.41 This estimator handled our small amount of missing data (1.19%) using pairwise deletion. We also applied oblique Geomin rotation that allows factors to be correlated. After finding the strongest evidence for the two-factor structure, we then tested this measurement model using CFA in another subsample and then examined measurement invariance by sex in this subsample.

To examine measurement invariance across adult males and females, we performed multiple-group CFA with the WLSMV estimation and theta parameterization42 using Mplus 7.0.40 After first specifying factor structures for males and females separately, we tested four models to evaluate measurement invariance: a configural invariance model as a baseline model; a weak/metric invariance model in which we constrained factor loadings to be equal between males and females; a strong/scalar invariance model in which we constrained both factor loadings and thresholds to be equal; and a strict invariance model in which we additionally constrained residual variances of measures to be equal. In addition to measurement invariance, we also tested whether the variances and means of latent factors differed between males and females. Effect size (ie, Cohen d) was calculated for mean differences in latent factors.43 Model fit indices used in the current study included the maximum-likelihood chi-square statistic (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).44 We applied the DIFFTEST option in Mplus to conduct chi-square difference tests between nested models as appropriate for WLSMV estimation.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

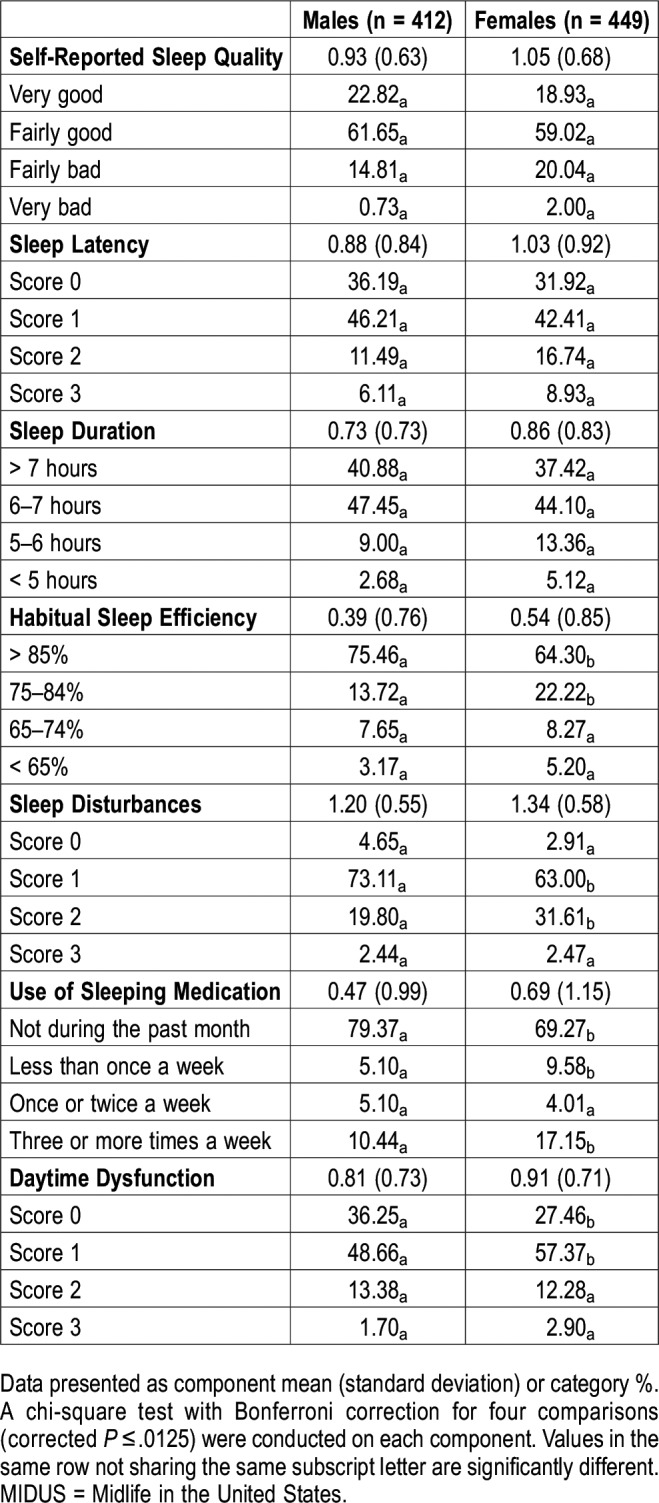

Table 1 shows response distributions for males and females on each sleep component. Most of the males and females self-reported fairly good to good sleep quality, 6 hours or longer of sleep each night, high sleep efficiency (> 85%), and no use of sleep medication in the past month. Notably, higher percentages of males tended to have relatively good sleep by reporting lower component scores (ie, 0) than females. Correspondingly, the percentages of females who had relatively poor sleep by reporting higher scores (ie, 1, 2, or 3) on each component was higher than that of males.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the seven components of sleep quality for the MIDUS refresher biomarker survey (n = 861).

Exploratory Factor Analysis

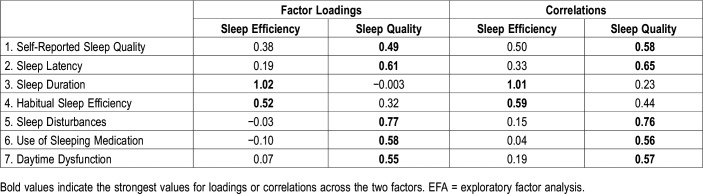

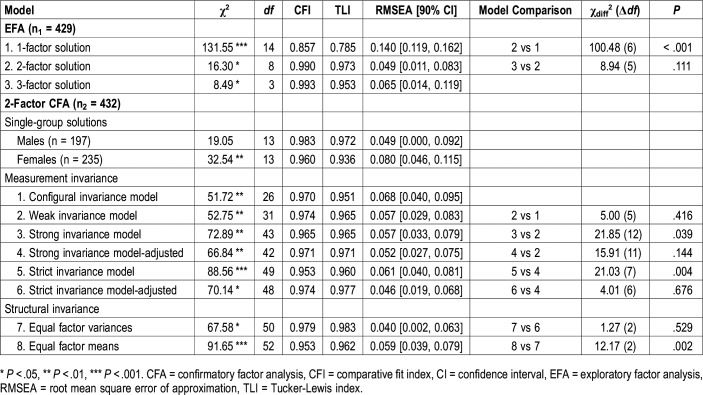

To examine the underlying structure of the PSQI, we tested EFA for one- through three-factor solutions in the first random subsample. The one-factor solution did not fit the data well (χ214 = 131.55, P < .001, CFI = 0.857, TLI = 0.785, RMSEA = 0.140, 90% confidence interval [CI ] = 0.119, 0.162), whereas both two- and three-factor solutions showed good fit (χ28 = 16.30, P < .05, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.049, 90% CI = 0.011, 0.083 for the two-factor solution; χ23 = 8.49, P < .05, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.065, 90% CI = 0.014, 0.119 for the three-factor solution). The unidimensional model with the general factor of Global Sleep Quality had factor loadings ranging from 0.43 to 0.71. The two-factor solution showed a statistically significant improvement in the model chi-square (χdiff62 = 100.48, P < .001) and other fit indexes, and the correlated factors (r = .23, P < .001) that emerged were readily interpretable.39 As shown in Table 2, the first factor, labeled “Sleep Efficiency,” included the components of sleep duration and habitual sleep efficiency. The second factor, labeled “Sleep Quality,” included the other five components: self-reported sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. In the 3-factor solution, the self-reported sleep quality, sleep duration, and habitual sleep efficiency loaded on the first factor, sleep latency, sleep disturbances, and use of sleeping medication loaded on the second factor, whereas daytime dysfunction loaded solely on the third factor. The three-factor model did not significantly improve the model fit in comparison with the two-factor solution (χdiff52 = 8.94, P = .111), and the third factor had only one indicator. Given the lack of improvement and interpretability concerns for the three-factor model, evidence from the EFA most strongly supported the two-factor model.

Table 2.

Geomin rotated factor loadings (pattern matrix) and correlations (structure matrix) for the seven components of the two-factor EFA for sample 1 (n1 = 429).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Measurement Invariance

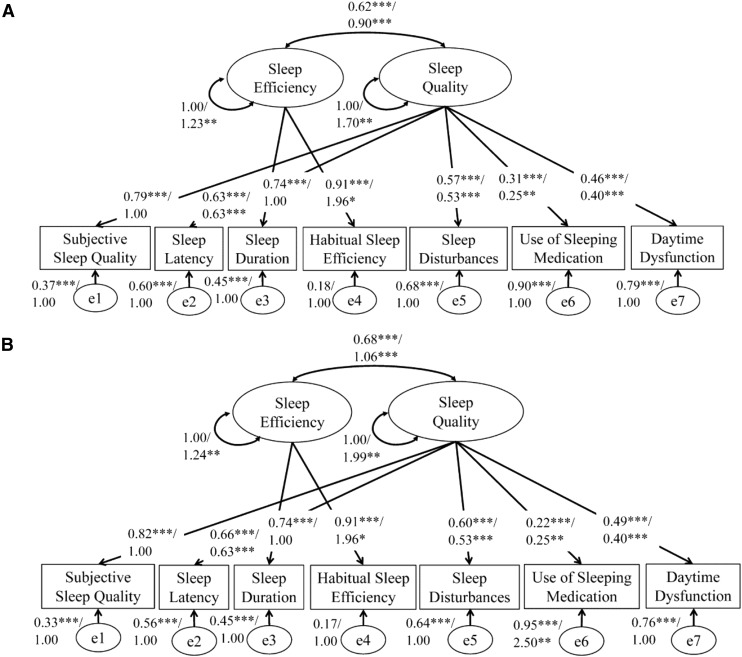

When tested in the second random subsample using CFA, the two-factor structure showed an acceptable fit to the data (χ213 = 46.45, P < .001, CFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.938, RMSEA = 0.077, 90% CI = 0.054, 0.102). We then tested measurement invariance between males and females in the random subsample for the two-factor structure using a series of models; model results are summarized in Table 3. The two-factor model fit the data well for both males and females, and the configural invariance model had good fit. The weak invariance model with factor loadings constrained to be equal between males and females did not significantly decrease the fit in comparison with the configural invariance model (χdiff52 = 5.00, P = .416). However, the strong invariance model with thresholds constrained fit significantly worse than the weak invariance model (χdiff122 = 21.85, P = .039). In accordance with model modification indices, we allowed one threshold of the sleep latency indicator to be freely estimated across males and females, and this modified strong invariance model did not fit significantly worse than the weak invariance model (χdiff112 = 15.91, P = .144). The strict invariance model with residual variances constrained to be equal between groups fit significantly worse than the adjusted strong invariance model (χdiff72 = 21.03, P = .004). However, when we allowed the residual variances for the use of sleeping medication indicator to be unequal between males and females, this adjusted strict invariance model did not show a significant decrease in the model fit than the adjusted strong invariance model (χdiff62 = 4.01, P = .676). Therefore, given the finding of invariance in the two-factor configuration, factor loadings, thresholds for all but one measure, and residual variances for all but one measure, we found evidence of minimal partial measurement invariance between males and females (Figure 1 shows model parameters for this final, adjusted strict invariance model). We note that constraints on residual variances are not required for valid comparisons of latent means.

Table 3.

Summary of fit indices from EFA and CFA-based tests of measurement invariance by sex of the two-factor structure.

Figure 1. The two-factor structure of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (n2 = 432).

(A) Males. (B) Females. All factor loadings, measures’ thresholds (except one threshold of Sleep Latency), and measures’ residual variances (except the Use of Sleeping Medication) were constrained to be equal between males and females. Standardized/unstandardized coefficients are separated by a slash. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001.

We then tested invariance of factor variances and means between males and females. The results indicated that factor variances were comparable between males and females (χdiff22 = 1.27, P = .529). Females had higher factor means for both Sleep Efficiency (χdiff12 = 4.89, P = .027; factor mean difference = 0.282, P = .056, Cohen d = 0.25) and Sleep Quality (χdiff12 = 9.96, P = .002; factor mean difference = 0.493, P = .004, Cohen d = 0.36), than males, indicating that females self-reported worse sleep than males.

Sensitivity Analyses: Other Factor Structures

Because some studies have advocated one-factor structure17 and Cole and colleagues’ three-factor structure36 for the PSQI, we also conducted CFAs and analyses of measurement invariance by sex for these alternative models on the overall sample. The summary of model results for the one- and three-factor structures are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Briefly, both the one-factor and three-factor structures fit the data well after we allowed for particular residual covariances between components of sleep measures. The one-factor model of the PSQI showed full measurement invariance across males and females, and the three-factor model showed partial measurement invariance between males and females (more detailed information can be found in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Model parameters of the strict invariance models for the one- and three-factor structures are presented in Figure S1 and Figure S2, respectively, in the supplemental material. Tests of structural invariance revealed that factor variances were comparable between males and females for both the one- and three-factor models. As observed for the two-factor models, the latent means for the one- and three-factor models indicate that females self-reported worse sleep than males. Overall, these results suggest that for each factor structure that was tested there was at least partial measurement invariance between men and women and women self-reported worse sleep than men.

DISCUSSION

Given the discrepant results regarding sex differences in perceived sleep quality,8,11 and the fact that measurement model differences can distort sex comparisons,27,28 we analyzed the potential influence of measurement invariance on sex differences in sleep and did so for multiple factor structures of the PSQI. Our findings suggest there are minimal differences between men and women in the factor structure underlying the seven-component PSQI, regardless of whether the PSQI is modeled with one, two, or three factors. Accordingly, the PSQI scores for men and women can be meaningfully compared. Thus, measurement model differences are likely not a major reason for the discrepant findings between men and women in self-reported sleep quality. Notably, when measurement invariance was accounted for, we found that women self-reported worse sleep than men.

Critically our results indicate that self-reported sleep quality, as measured by the PSQI, is perceived and interpreted in the same way in men and women. Specifically, configural equivalence was supported in all three factor structures of the PSQI, indicating that the forms of the factor model are comparable across men and women. Weak measurement invariance was also supported for all three structures, showing that the relationships between the underlying latent variables and the seven components of the PSQI are equally strong for men and women. Full strong measurement invariance was supported for the one-factor structure, and partial strong measurement invariance for the two- and three-factor structures, showing that comparisons of latent variables of the PSQI between men and women are meaningful.45 Hence, our findings provide evidence that sex differences of the PSQI are likely to reflect “true” differences in self-reported sleep quality between men and women rather than measure bias or measurement model differences, at least among American adults. Thus, the PSQI can be used by researchers and clinicians to compare men and women in their self-reported sleep quality.

For all three measurement models, and even after the strictest measurement assumptions were employed, we found that women self-reported worse sleep than men. These results are consistent with a number of previous studies using the PSQI8,14,35 and with other studies indicating that women are at greater risk for insomnia.7 Future researchers should continue to investigate why such sex discrepancies exist and examine whether there are different precursors and consequences of self-reported sleep quality for men and women. We also urge these researchers to carefully examine the measurement properties of the PSQI between men and women, especially if this research is conducted in populations aside from American adults.

Our finding that EFA favors a two-factor structure of the PSQI over one- and three-factor structures is not surprising, considering the high correlation between Perceived Sleep Quality and Daily Disturbances in our three-factor structure for both men and women. Additionally, this two-factor structure has also been suggested in studies of Chilean, Ethiopian, Thai,31 Caucasian,32 Chinese,33 and Australian populations.34 The two-factor model of the PSQI has several advantages such as being more parsimonious compared to the seven-component PSQI and providing error-free estimates of the seven components by modeling measurement error. Therefore, we suggest that future researchers consider the multidimensionality of the PSQI and examine whether the different dimensions of the PSQI are associated with different substantive findings.

There are three important limitations of our study. First, our focus in this study was on potential measurement model differences by sex but it is also important to examine in future research the measurement properties of the PSQI across national context, age group, and ethnicity. In particular, worse sleep quality has been reported at older ages8 and for African Americans,2,46 so these populations may be of particular interest. Unfortunately, small cell sizes (eg, 91 nonwhite men and approximately 45 for a half sample) precluded our ability to study this adequately with the current sample. Further, the underlying structure of the PSQI has been found to vary across countries.31 Thus, we hope our research will draw further attention to the need for investigating measurement invariance of the PSQI and other sleep-related scales when comparing population subgroups (eg, race/ethnic group, age group, clinical/nonclinical samples, etc.). Second, caution should be used in generalizing these findings regarding measurement invariance between men and women without consideration for other populations (eg, among adolescents or in other countries). Third, it is worth noting that most of the adults in our sample (79.37% of men and 69.27% of women) did not report using sleeping medication, and this component had low loadings on latent variables for men and women in all three structures examined, especially in the two-factor structure. Similar low levels of use of sleeping medication and poor loadings have also been reported for Portuguese,47 non-Hispanic white and Mexican Americans,23 and Asians.39 This suggests that the use of sleeping medication may not be a good indicator of perceived sleep quality. However, when we conducted ancillary analyses excluding the sleep medication measure, we found substantively similar results in terms of the measurement invariance and factor mean differences between men and women.

Our analyses offer evidence that the PSQI is a valid basis for sex comparisons of perceived sleep quality. This finding holds methodological and practical implications for researchers investigating issues relevant to self-reported sleep quality and for clinicians using the PSQI as an initial assessment of sleep patterns and sleep quality. For example, the measurement invariance of these factor structures of the PSQI has important implications for intervention programs. That is, having a sex invariant instrument may be valued for researchers and clinicians who want to assess sex differences or determine whether interventions have differential effects on men and women. Additionally, we have shown that women self-reported worse sleep quality than men. As sleep is associated with mental and physical well-being, poorer sleep among women could be an important mechanism that reinforces sex-based differences in health and other domains. Researchers should continue to analyze why women self-report worse sleep than men and ways to potentially combat this sex discrepancy in sleep. Overall, as data sources and complex statistical methods become increasingly accessible, we urge researchers to continue to formally test and check assumptions of these data and methods as these checks are critical for understanding the question being researched.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at Arizona State University. This research was supported in part by funding from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University for research support. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of Arizona State University.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CFA

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI

comparative fit index

- CI

confidence interval

- EFA

exploratory factor analysis

- MIDUS

Midlife in the United States

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SD

standard deviation

- TLI

Tucker-Lewis index

- WLSMV

weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted

REFERENCES

- 1.Reid KJ, Martinovich Z, Finkel S, et al. Sleep: a marker of physical and mental health in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(10):860–866. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000206164.56404.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis DS, Fuller-Rowell TE, El-Sheikh M, Carnethon MR, Ryff CD. Habitual sleep as a contributor to racial differences in cardiometabolic risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(33):8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618167114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H-C, Su T-P, Chou P. A nine-year follow-up study of sleep patterns and mortality in community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan. Sleep. 2013;36(8):1187–1198. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien M-Y, Chen H-C. Poor sleep quality is independently associated with physical disability in older adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(3):225–232. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivertsen B, Krokstad S, Øverland S, Mykletun A. The epidemiology of insomnia: Associations with physical and mental health. The HUNT-2 study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemola S, Ledermann T, Friedman EM. Variability of sleep duration is related to subjective sleep quality and subjective well-being: an actigraphy study. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, Wing Y-K. Sex differences in insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29(1):85–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang J, Liao Y, Kelly BC, et al. Gender and regional differences in sleep quality and insomnia: A general population-based study in Hunan Province of China. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):43690. doi: 10.1038/srep43690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goel N, Kim H, Lao RP. Gender differences in polysomnographic sleep in young healthy sleepers. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(5):905–915. doi: 10.1080/07420520500263235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright H, Carskadon MA. The discrepancy between actigraphic and sleep diary measures of sleep in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2012;13(4):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Berg JF, Miedema HME, Tulen JHM, Hofman A, Neven AK, Tiemeier H. Sex differences in subjective and actigraphic sleep measures: A population-based study of elderly persons. Sleep. 2009;32(10):1367–1375. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.10.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackowska M, Dockray S, Hendrickx H, Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors and sleep efficiency: Discrepancies between subjective and objective evaluations of sleep. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(9):810–816. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182359e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J-N. Gender differences in self-perceptions about aging and sleep among elderly Chinese residents in Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2016;24(4):347–356. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fatima Y, Doi SAR, Najman JM, Al Mamun A. Exploring gender difference in sleep quality of young adults: Findings from a large population study. Clin Med Res. 2016;14(3-4):138–144. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy JF, Cain SW, Chang A-M, et al. Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(Supplement 3):15602–15608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauderdale DS. Survey questions about sleep duration: does asking separately about weekdays and weekends matter? Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12(2):158–168. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.778201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mollayeva T, Thurairajah P, Burton K, Mollayeva S, Shapiro CM, Colantonio A. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:52–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543–1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2008;9:S10–S17. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, et al. Insomnia with short sleep duration and mortality: the Penn State cohort. Sleep. 2010;33(9):1159–1164. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrne BM, Watkins D. The issue of measurement invariance revisited. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2003;34(2):155–175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomfohr LM, Schweizer CA, Dimsdale JE, Loredo JS. Psychometric characteristics of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in English speaking non-Hispanic whites and English and Spanish speaking Hispanics of Mexican descent. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(1):61–66. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen P-Y, Jan Y-W, Yang C-M. Are the Insomnia Severity Index and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index valid outcome measures for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia? Inquiry from the perspective of response shifts and longitudinal measurement invariance in their Chinese versions. Sleep Med. 2017;35:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schredl M, Reinhard I. Gender differences in nightmare frequency: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15(2):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgard SA, Ailshire JA. Gender and time for sleep among US adults. Am Sociol Rev. 2013;78(1):51–69. doi: 10.1177/0003122412472048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera-Medina CL, Caraballo JN, Rodríguez-Cordero ER, Bernal G, Dávila-Marrero E. Factor structure of the CES-D and measurement invariance across gender for low-income Puerto Ricans in a probability sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(3):398–408. doi: 10.1037/a0019054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan CM, Tucker-Drob EM. Gendered expectations distort male–female differences in instrumental activities of daily living in later adulthood. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(4):715–723. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van De Schoot R, Schmidt P, De Beuckelaer A, Lek K, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg M. Editorial: measurement invariance. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1064. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manzar MD, BaHammam AS, Hameed UA, et al. Dimensionality of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0915-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelaye B, Lohsoonthorn V, Lertmeharit S, et al. Construct validity and factor structure of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in a multi-national study of African, South East Asian and South American college students. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e116383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otte JL, Rand KL, Carpenter JS, Russell KM, Champion VL. Factor analysis of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chong AML, Cheung C. Factor structure of a Cantonese-version Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2012;10(2):118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magee CA, Caputi P, Iverson DC, Huang X-F. An investigation of the dimensionality of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Australian adults. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2008;6(4):222–227. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(6):563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole JC, Motivala SJ, Buysse DJ, Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Irwin MR. Validation of a 3-factor scoring model for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in older adults. Sleep. 2006;29(1):112–116. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinstein M, Ryff CD, Seeman TE. Midlife in the United States (MIDUS Refresher): Biomarker Project, 2012-2016 (ICPSR 36901) https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/36901. Published August 14, 2019. Accessed October 17, 2019.

- 38.Barry TR. The Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) series: a national longitudinal study of health and well-being. Open Health Data. 2014;2(1) doi: 10.5334/ohd.ai. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manzar MD, Zannat W, Moiz JA, et al. Factor scoring models of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a comparative confirmatory factor analysis. Biol Rhythm Res. 2016;47(6):851–864. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User’s Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012; [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):354–373. doi: 10.1037/a0029315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol Methods. 2004;9(4):466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson MS, Green SB. Evaluating between-group differences in latent variable means. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, eds. A Second Course in Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2013:163-218. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(3):456–466. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheehan CM, Frochen SE, Walsemann KM, Ailshire JA. Are US adults reporting less sleep? Findings from sleep duration trends in the National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. Sleep. 2018;42(2) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker NB, de Neves Jesus S. Adaptation of a 3-factor model for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Portuguese older adults. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.