Abstract

Study Objectives:

The aim of this qualitative analysis was to identify obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients' preferences, partner experiences, barriers and facilitators to positive airway pressure (PAP) adherence, and to assess understanding of the educational content delivered and satisfaction with the multidimensionally structured intervention.

Methods:

A qualitative analysis was conducted on 28 interventional arm patients with a new diagnosis of OSA. They received a one-on-two semistructured motivational interview as the last part of a 60- to 90-minute in-person educational group intervention. The 10- to 15-minute interview with the patient and caregiver was patient-centered and focused on obtaining the personal and emotional history and providing support. We also assessed understanding of the OSA training plan, their commitment to it, and their goals for it.

Results:

We identified four themes: OSA symptom and diagnosis, using the PAP machine, perceptions about the group visit, and factors that determine adherence to PAP. Patients experienced positive, negative, or mixed emotions during the journey from symptoms of OSA to PAP adherence.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that patients’ and caregivers’ positive experiences of PAP could be enhanced by a patient-centered interaction and that it was important to explicitly address their fears and concerns to further enhance use of PAP. Not only could caregiver support play a role in improving PAP adherence but also the peer coaching session has the potential of providing a socially supportive environment in motivating adherence to PAP treatment.

Citation:

Khan NNS, Olomu AB, Bottu S, Roller MR, Smith RC. Semistructured motivational interviews of patients and caregivers to improve CPAP adherence: a qualitative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(12):1721–1730.

Keywords: motivational interview, obstructive sleep apnea, patient and caregiver engagement, patient-centered interview, positive airway pressure, qualitative analysis

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: There is only limited evidence that partner engagement in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) improves adherence to positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. This analysis evaluates patients' preferences, caregiver experiences, and barriers and facilitators to PAP adherence; it also evaluates understanding of the educational content and satisfaction with the intervention.

Study Impact: This analysis identifies several emotions experienced with the OSA diagnosis and its PAP treatment. It also emphasizes the need for patient-centered interventions to bring a positive change in the patient and caregiver experience.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has increased over the past two decades, largely because of its association with obesity. It is estimated that 6% to 17% of adults have OSA, the prevalence as high as 49% in those of advanced age.1,2

Adherence to positive airway pressure (PAP), the cornerstone therapy for OSA, is commonly defined as use of PAP > 4 h/night. It is known to improve sleep quality, reduce daytime symptoms, and improve the overall quality of life.3 Untreated OSA increases risks of hypertension,4 stroke,5,6 glucose intolerance,7 atrial fibrillation,8 and traffic accidents due to drowsiness.9 Despite the benefits and clinical effectiveness of PAP, nonadherence varies from 29% to 83%.10 Recent evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials11 confirms that the use of PAP ≥ 4 h/night not only improves the quality of life by having a positive effect on mood and reducing daytime sleepiness but also might reduce major adverse cardiovascular events and stroke.

Studies have evaluated the efficacy of individual and group education sessions,12–18 brief motivational enhancement,19–22 additional home visits,23–25 telemedicine,26 and Web access27 and showed that these interventions result in better PAP adherence. One study surveyed patients with OSA to measure spousal involvement and demonstrated that perceptions of collaborative spousal involvement were associated with adherence.28 Another survey of married patients with OSA demonstrated that level of spousal involvement was associated with increased continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) adherence at 6 months.29 Bouloukaki et al in their intensive versus standard follow-up study had required the patient to bring partner or family to follow-up care; however, which component of the intensive treatment produced the major effect in improving PAP adherence was not assessed.16 The findings of the first qualitative analysis of both patient and partner experiences30 with OSA and the results of the first randomized controlled trial of couples intervention supports engagement of partners in improving PAP adherence.31 A recent observational study demonstrated that a high-quality marital relationship is a significant moderator of PAP adherence.32 There is also evidence that peer coaching could help improve PAP adherence.33

Our study, also known as the Improving CPAP Adherence Program (I-CAP) study, aimed to provide a multidimensional treatment framework based on shared decision-making, patient activation, and caregiver engagement. We hypothesized that our I-CAP study would promote and support active patient participation, and that it would engage the caregiver to enhance long-term PAP acceptance and adherence.

METHODS

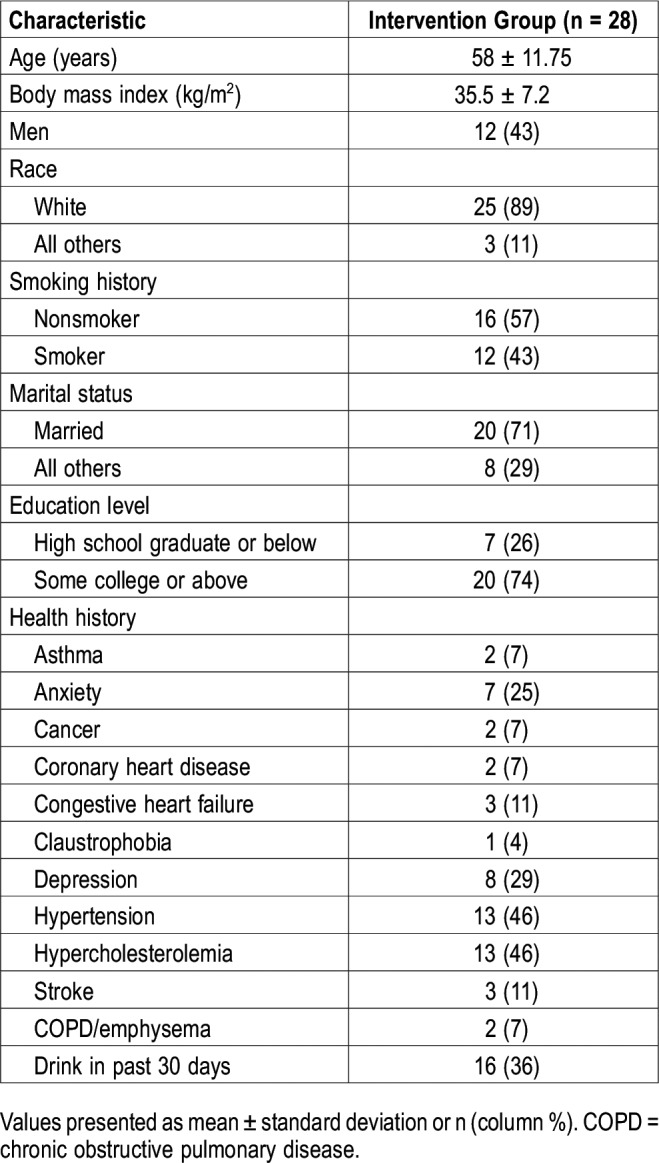

The overarching I-CAP study, of which the current report is one part, was a randomized controlled, parallel group clinical trial to assess the effect of patient and caregiver engagement in improving PAP adherence in patients with OSA (n = 60). The Michigan State University Institutional Review Board approved the study. After a pilot group visit involving a patient and their caregiver, the protocol was finalized, the randomization scheme was generated, and patients were assigned to intervention (n = 28) or attention control arms (n = 32).

All randomized participants and their caregiver participated in a single 60- to 90-minute in-person group visit a few weeks after receiving the PAP machine—the focus of this qualitative analysis. In our attention control design, the control group patients and their caregivers were educated on physical activity and lifestyle modification. The comparison of outcomes between the two groups will be presented in a separate article.

Intervention Group Visit

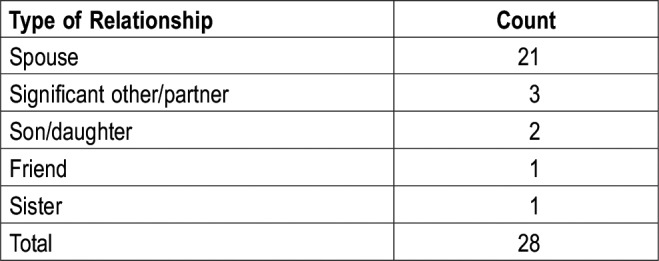

Patients and their caregiver (partner) participated in the group visit from 1 to 17 weeks of receiving the PAP machine (Table 1). Thirteen intervention group visits (one to three patients with their caregiver at each group visit) were held during the course of the study (Table 2). The goal of having a caregiver at the intervention visit was to empower the caregiver and develop understanding of the goals and purposes of the PAP treatment and to provide support to the patient.

Table 1.

Self-reported baseline characteristics of the intervention arm patients.

Table 2.

Caregiver’s relationship with the patient.

Structure of the Intervention Arm Group Visit

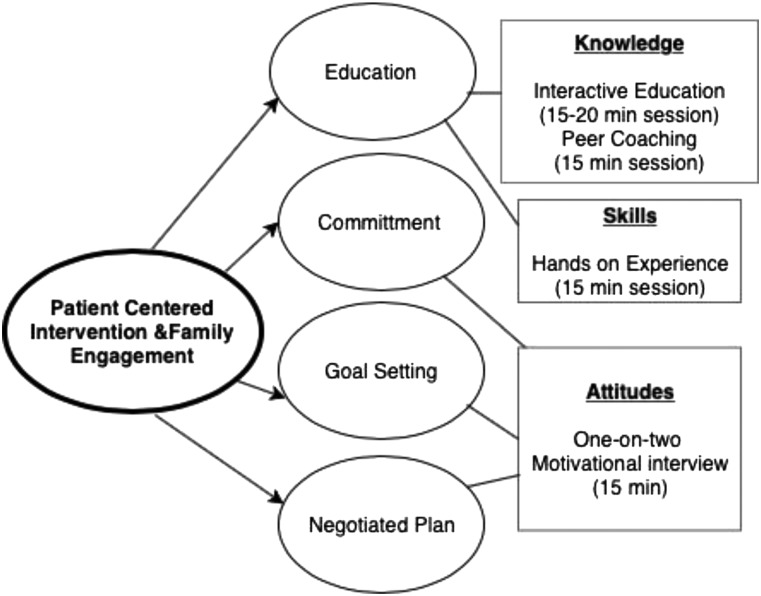

The four sessions of the group visit (Figure 1) were: (1) an interactive educational session, which was based on the guidelines from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)34 and focused on educating participants on OSA, its effect on health, ways to mitigate OSA and its symptoms, PAP and its effects, and the importance of family/partner support; (2) peer coaching from a patient with OSA and PAP user; (3) hands-on experience with the PAP machine from a respiratory therapist; and (4) one-on-two semistructured motivational interview with each patient along with his or her caregiver. The motivational interview was conducted in a private room with each patient and his or her caregiver.

Figure 1. Schematic layout of the I-CAP study group visit.

I-CAP = Improving CPAP Adherence Program.

The one-on-two motivational interviews were designed to gauge participants’ willingness and ability to adhere to PAP treatment while also providing encouragement and offering advice to improve adherence. The interview also incorporated the first three sessions of the group visit. It explored how the OSA diagnosis and use of the PAP machine affected participants’ lives and lifestyles—particularly at an emotional level. We also determined the knowledge and awareness participants gained from the program sessions.

Framework for the Motivational Interviews

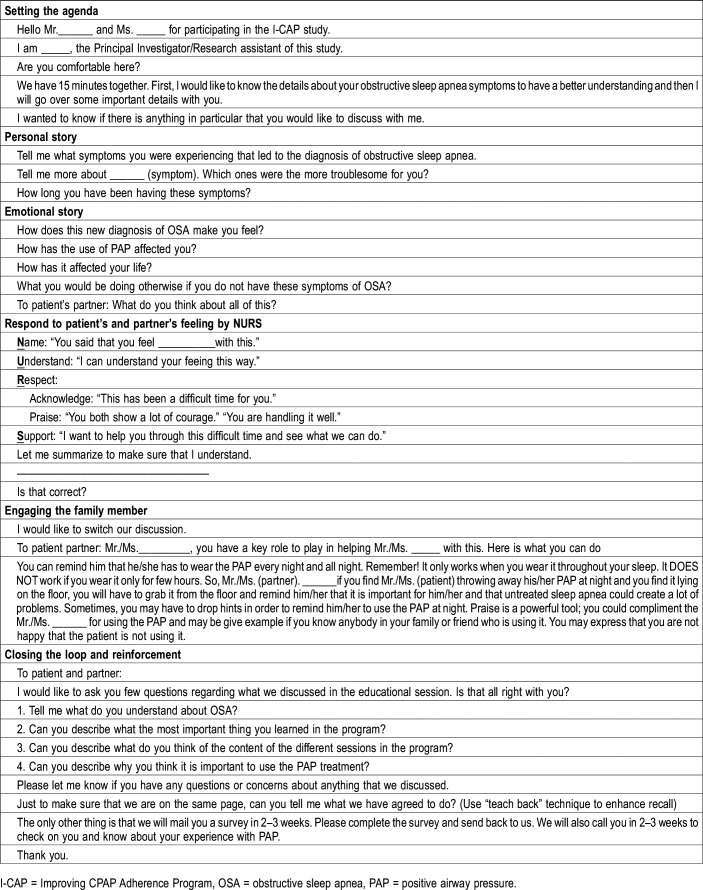

The semistructured motivational interview was based on an evidence-based patient-centered interviewing method35,36 integrated with motivational interview principles and was formulated by one of the authors (RS) (Table 3).

Table 3.

One-on-two patient-centered semistructured motivational interview.

First, we set the stage for the interview. This was followed by a patient-centered interaction, during which we obtained a brief account of patients’ symptoms to develop the psychological and social context of patient’s symptoms. Then we elicited the emotional history to develop an emotional context to patient’s symptoms. We next responded to patient’s and partner’s emotions using these empathic skills: Name the emotion, Understand the emotion, Respect the emotion, and Support the emotion), recalled by the mnemonic NURS.36

We checked patient/caregiver understanding and engaged pairs in the educational component. We next obtained commitment from the patient and the partner and ascertained their long-term goals as a way to highlight the benefits that might accrue. We reviewed the plan and took into account feedback so that the plan was satisfactory. To close, we used the teachback technique to assess patient and partner understanding of the disease process and obtain a commitment from the patient to be PAP adherent.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted to derive the underlying constructs in the 28 patient-partner motivational interviews. Thematic analysis is a flexible, inductive method for identifying, analyzing, and describing themes (or patterns) in the data.37,38 Unlike a grounded theory approach, by which the goal is to derive a particular theoretical framework determined solely by the data being analyzed interactively, thematic analysis liberates the researcher to freely discover and examine patterns across an entire dataset wherever the journey leads.

Our thematic analysis examined the data on the level of both manifest and latent content. By looking beyond obvious manifest content, such as particular words participants used to describe an emotion, our analysis purposefully examined the latent meaning within the data by focusing on the context of participants’ comments. This inductive approach to find the contextual meaning of the data is designed to foster insights leading to the discovery and enrichment of themes. For example, the positive emotion associated with the knowledge participants gained during the educational session of the group visit is more deeply understood when considered within the context of participants’ other health conditions and their sensitivity to health risks.

Both written transcripts and audio recordings of the interviews were used in all analyses. Making use of the transcripts as well as the recordings (rather than the transcripts alone) allowed for the cross-checking of the data, assured that the data were complete and accurate, strengthening the validity of the analysis, and offered a way to go beyond an analysis of just the words that were said and to actually hear the manner (ie, the emotion) in which participants’ words were spoken. The analysis was conducted by an expert qualitative methodologist (MRR) utilizing a process not unlike the familiar six-step thematic analysis process espoused by Braun and Clarke37 and the inductive content analysis process discussed by Elo and Kyngäs39 and Luyster et al.31 The unit of analysis was an entire interview. The process involved absorbing the content of each interview; identifying the key attitudes, behaviors, and emotions associated with each stage of the OSA experience; looking across the entire interview to identify common themes; searching for common themes across all interviews; defining and naming these themes; and drawing interpretations from the data.

Importantly, our thematic analysis was focused on extracting the contextual meaning across the entire qualitative data set rather than deriving narrowly defined quantifiable measures. As such, our results do not report the number of times a particular idea was mentioned or otherwise give a numeric justification for the data interpretation, an approach more suitable for a quantitative data set based on discrete items.

RESULTS

Of the 28 participants in the motivational interview portion of the I-CAP study, 16 were women and 12 were men.

The analysis considered patients’ attitudes, behaviors, and emotions associated with the four stages of their OSA experience:

-

1.

OSA symptom and diagnosis

-

2.

Using the PAP machine

-

3.

Perceptions about the group visit

-

4.

Factors that determine adherence to PAP

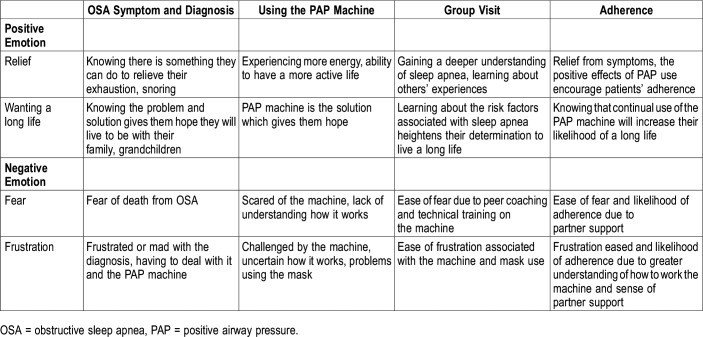

Looking across the four stages, our findings reveal four—two positive and two negative—emotional themes that patients typically feel throughout the OSA experience. The sense of relief and the desire to live a long life are the two positive underlying emotions, whereas fear and frustration are the two negative emotions that research participants experience in varying levels of intensity. These key emotions, and their association with each of the four stages, are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key emotional themes throughout the OSA experience.

The results from our data analysis are discussed within the context of the four aforementioned stages. Throughout this discussion, we draw upon the four key emotional themes associated with each stage.

OSA Symptoms and Diagnosis

It is worth noting that many of these patients initiated the sleep study themselves. In some cases this was at the urging of his or her partner, who raised concerns about the patient’s excessive snoring (and “breathing episodes”) or tiredness; in other cases, the patient took the initiative when the physician did not detect a problem or otherwise said after an examination that everything “looked fine.”

“So, I just did it…I scheduled [the sleep study] for when [my doctor] would be out of town. [The provider] didn’t even know I was doing it.”

This is an important backdrop to these interviews because it speaks to the emotion of “relief” discussed earlier (eg, wanting to find relief from their symptoms) and, specifically, the degree to which some patients were self-motivated and predisposed to their OSA diagnosis.

Patients who did not initiate their sleep study were typically referred by a physician who they were seeing for other reasons, eg, a cardiologist examining the patient for underlying causes of a stroke or a general practitioner performing a routine checkup. One participant being seen for dementia was referred by the psychologist.

Positive Attitude With the Diagnosis

Patients were generally unfazed (“I didn’t think it was that big a deal”) or not surprised (“sleep apnea is quite regular in my family”) to receive the OSA diagnosis. In many instances, the diagnosis was a relief for two primary reasons: (1) it identified the cause of symptoms—particularly fatigue, “I’m exhausted all the time”—which patients had typically lived with for many years (in some cases, decades) and/or (2) it was a condition that is “fixable” by way of the PAP machine. It is the promise embedded in the OSA diagnosis—the relief from exhaustion (mostly from the patient’s perspective) and snoring (mostly from the partner’s perspective)—that effectively stimulates a positive emotional response coupled with a determined “can-do” attitude.

“I felt positive that if I used the treatment that I would be fine.”

“I know it’s not my heart now, so I’m comfortable with that…Now I’m anxious to get to feeling better so I can walk. I’m willing to try anything to get better.”

“I was relieved to be diagnosed. Now I know what I have and now I need to find out how I need to treat it.”

“[It is] good that they discovered [OSA] and there is something that could help me. I’d try everything to get better.”

Negative Attitudes of Fear and Frustration With the Diagnosis

It was not uncommon for patients to be “afraid” or “scared” upon receiving the OSA diagnosis because they feared the worst, that is, that they could die from OSA if it was left untreated.

“What if one time I quit breathing and I don’t come back…I’m going to pass in my sleep.”

“Well, [I was] a little depressed at first. I don’t want to die in my sleep.”

For others, the diagnosis raised a dread of having to use the PAP machine.

“[The diagnosis] didn’t bother me all that much until I got the machine and I thought ‘Oh boy, this is the rest of my life…I don’t like this at all.’”

This was particularly worrisome for a patient who used a PAP machine 5 years ago and found the experience “very frustrating” (due to problems with condensation), which caused the patient to stop using it.

Using the PAP Machine

Not surprisingly, the strongest negative responses—“frustrated,” “mad,” “not satisfied,” “annoying”—to the OSA experience revolve around utilization of the PAP machine. Even patients who had been proactive in gaining a sleep test and had a “positive view” of their diagnosis and its treatment voiced serious frustrations and “challenges” with their attempts to use the PAP machine. Although a few patients complain that the mask looks “silly” or “unattractive” or interferes with “cuddling up,” patients’ concerns generally extend to problems with the mechanics of using the PAP machine, which lead to “annoying” discomfort and ultimately to inadequate sleep.

“The very first night I had [the mask] on four hours and I was struggling.”

“[PAP is] driving me crazy. All of a sudden it would blast air in my face for no reason.”

“I just couldn’t get comfortable with [the PAP machine] because it seemed like I couldn’t really breathe with the air pressure going on.”

The most common problems reported with the PAP machine have to do with the mask—adjusting it and placing it on the face so that it does not leak or come off during the night—and which side of the bed to put the machine, “I don’t know what to do with the hose and stuff.” And, indeed, it is the patient’s uncertainty and lack of know-how when using the PAP machine that leads to frustration and a suboptimal PAP experience.

“I think [PAP] is a big challenge because I haven’t been very successful. I just don’t know how to work it.”

Importantly, there are two key elements that serve to mitigate patients’ negative reactions to the PAP machine and potentially motivate them to adhere to treatment. One key element is the emotional relief patients experience because PAP is making a positive difference in their lives by way of reducing the most significant symptoms of tiredness and, particularly for the partner, snoring.

“I don’t feel as tired.”

“I think I feel better now than I have in a long time.”

“I am more energetic.”

“I don’t sleep during the day.”

“[The snoring has] calmed so much.”

This effect has been strikingly pronounced for one patient who enthusiastically stated

“Oh, [PAP] immediately changed me. [The first] morning, I woke up and felt like a different person. I don’t understand anybody that doesn’t do good on it because it makes you feel so much better.”

Another key element to mitigating patients’ negative reactions to the PAP machine is their strong association between PAP and a long and healthy life. The discussion in the I-CAP educational session about the potential for other health issues, such as heart disease and stroke, helped to fuel this association and make it a motivating force (ie, doing whatever is necessary to live a healthy life), particularly among patients and partners who have grandchildren.

“I want to be healthy, I want to live. I'm going to get a new grandbaby and I want to live. I don't want to sit in a chair the rest of my life.”

“It is not fair to my grandkids. I want to be able to see them grow up a little bit more.”

“I want to see my grandkids graduate from college.”

“I want to [use PAP] because I have grandkids that I want to be around for.”

Perceptions About the Group Visit

Participants’ reactions to the group visit were uniformly positive, characterized by an emotional sense of relief and ease of fear and frustration. Overall, they described the 1-hour visit as “very informative.” Participants appreciated the variety of sessions—stating that each session gave them new and useful content or perspective—and many were reluctant to single out any one session as their “favorite,” emphasizing instead “the whole package.”

“The structure is really good because it was informational, it was the emotional side, it was the machine side. I mean, you covered all the bases.”

The diversity, usefulness, and “pace” of the sessions (ie, the sessions were not “drawn out,” presenters “got to the point” quickly), resulted in the feeling that the group visit had been “very helpful [and] very worth our time.”

Recall of the Knowledge Gained During the Educational Session

From the educational session, participants were particularly interested in learning about the “deeper problems” associated with OSA, most often recalling information having to do with the implications for heart disease as well as stroke, diabetes, and the possibility of death. This information appears to have struck a chord with these participants and reinforced the idea that treatment “keeps you healthy.” It should be noted that participants’ recall and sensitivity to the health risks linked to OSA may be related to the fact that many of these patients already have a variety of health issues (eg, high blood pressure and cholesterol, diabetes) in addition to being overweight. These patients knew all too well the health-related consequences of certain behavior, which may make them particularly interested in this type of information.

Participants also recalled information pertaining to the mechanical aspect of what causes OSA, stating that:

“You are not getting enough air in your lungs [and] stop breathing.”

“The throat actually closes off because of your tongue.”

“Your muscles relax in the back of your throat and it blocks your airway.”

“[OSA] involves my airway not contracting like it is supposed to.”

“[OSA] usually affects people that have a thicker neck or more chins. When you go down to sleep, you are not getting the proper airflow throughout your body and your organs.”

A few patients specifically mentioned the effect of OSA on the brain—“Your brain says ‘Hey, I’m not getting enough oxygen’ so you’re waking up a lot…”—with one participant asserting:

“[OSA] affects the brain…a part of the brain that is supposed to tell you to breathe while you are sleeping. [If] that part isn’t functioning, [the] brain isn’t telling [the patient] to breathe, then that’s a problem.”

Importantly, this information on the mechanical causes of OSA reinforced the importance of using the PAP machine—“[PAP] forces air into your air passages so that you are getting a steady supply [and it] keeps those muscles from collapsing.”

Other content in the educational session was mentioned less frequently or not at all. A few patients recalled that the PAP machine should be used when napping, that the patient should sleep on his/her side rather than on the back, that the consumption of alcohol can exacerbate OSA, and that there is a genetic component to OSA. Interestingly, no one mentioned the information given to participants on the importance of walking or the weight loss information sessions at Sparrow Hospital (a nearby Michigan State-affiliated medical facility). One assumption is that these areas of content in the educational session were not mentioned because it may not be new information (ie, participants are already aware of the importance of walking and weight loss). Future interviews may want to explore reasons why participants fail to mention certain portions of the educational content.

Assessment of the Peer Coaching Session

Peer coaching was an important, useful, and stress-relieving session for participants. The peer coaching session aroused the positive emotions of relief as well as the easing of fear. It was cathartic for participants to hear from someone who has been through the OSA experience and PAP treatment. In addition to learning about “procedural alternatives” such as surgery—“[The peer coach] had to have their face moved, [that’s] scary”—participants found it “really helpful” to hear someone talk about their experiences and empathize with patients’ experiences using the PAP machine.

“It was nice to hear somebody else have the same frustration…[The peer coach] didn’t like [the mask] on their face and I’m going Yes!”

Important to adherence, patients gain a strong feeling of encouragement when learning about others’ experiences and having others involved in their condition—“Encouragement like that helps.” It is the encouragement from peers and partners that help to positively affect adherence.

Assessment of the Hands-on Experience Session

As discussed earlier, a fundamental deterrence to adhering to treatment is the patients’ lack of skills or knowledge associated with using the PAP machine. Although the provider of the machine gave patients some information, it was this hands-on session where many of their questions and problems with the machine were addressed. The highly practical content of this session raised an emotional sense of relief while giving participants confidence and, in some cases, new motivation to use the PAP machine.

“With the knowledge that I have learned tonight, I am kind of excited about going back and reusing [the PAP machine].”

The two areas of content in this session that participants seemed to value the most are: (1) cleaning the machine (something they knew little or nothing about prior to this session), including how to clean it and that “cleaning it the right way is vital” and (2) the therapist’s discussion of the mask. It is because patients “struggle” with the mask—possibly making this the single greatest impediment to adhering to treatment—that made them naturally receptive to the therapist’s remarks on how to adjust the mask and the importance of “wearing your equipment the right way.” For instance, in one case, the therapist showed the patient how to adjust both sides of the mask and, in another case, the therapist made mask adjustments for a patient who was routinely “frustrated” and “mad” because the mask leaked.

Factors That Determine Adherence to PAP

The 28 one-on-two interviews conducted with program participants reveal a variety of potential influences on adherence to PAP treatment.

Support: Partner and Peer

The single overarching influence on adherence revolves around partner support. Indeed, it is the supportive involvement of the partner that has proven to stimulate needed attention to the patient’s symptoms (by “bugging” the patient to schedule a sleep study) while also encouraging the patient’s use of the PAP machine, saying things such as

“It will be okay, it will be okay. I know it’s hard…”

“Put it on, put it on.”

“I’m so proud of [spouse] for doing it [using the PAP machine].”

It should be noted that at least some of this supportive attention is derived from the partner’s own experience with OSA and sense of relief from using the PAP machine. Some of the partners currently use PAP, or have in the past, and can attest to its benefits—“I don’t have to sleep as many hours as I used to”—which they pass on to the patient—“[My spouse] has seen how good [the PAP machine] has helped me.”

Similarly, patients are encouraged by other family members or friends who have OSA, use the PAP machine, and who have benefitted from the treatment —“Knowing a number of people that have the machine eliminates stigma entirely.”

The positive effect of others’ involvement with the patient’s condition and the particular importance of partner support have been reported by Elfström et al40 and Luyster et al.29 Our findings suggest that the positive role of partner support extends to the positive effect of the peer coaching session in the group visit, both of which demonstrate the potential value of a socially supportive environment in motivating adherence to PAP treatment.41,42

Attitude: Wanting to Live and Determination

Another human and highly emotional factor that serves to motivate adherence to treatment is the role of close family ties, particularly grandchildren and spouses, and the desire to live that is fostered by these relationships—partner to spouse: “I want you to be an old dude with me.” The importance of grandchildren and wanting to live a healthy life were discussed previously.

Along with “wanting to live,” is the importance of a positive, determined attitude. For some, this attitude stems from family ties but for others it may come from a positive result after using the PAP machine or from a personality type that sets out to achieve a goal.

“I am a determined person. If I make up my mind it will happen. I will do it.”

“It’s different so I have to adjust to it being different, that’s all.”

“I’ll get used to it and I’m going to keep on using it.”

As a form of commitment, several patients talked about the importance of having a plan or somehow making the use of the PAP machine “routine” so, as one patient quoting the peer coach said, “it becomes part of you.”

Knowledge: OSA and the PAP Machine

These interviews underscore the idea that knowledge is power; this means that the gaining of new information seemed to foster enthusiasm among participants and a renewed willingness to commit to the PAP treatment. This was evident in participants’ reactions to the:

OSA diagnosis and details of OSA

“Now I know what I have and now I need to find out how to treat it. Information is knowledge.”

“[The most important thing I learned is] all the other things that [OSA] could do besides me losing my breath…the other things that it can cause. It will make me more serious about using it every day and…when I rip it off to make sure I put it back on.”

PAP machine

“[I learned that] having the proper equipment, wearing your equipment the right way, and cleaning it the right way is vital. And making sure that you…keep in touch with what your readings are…I’m looking forward to doing that.”

“[The] old machines were not only big but loud and noisy.”

“You just hear that little noise of the oxygen and it's kind of soothing if you think about it…It's not a loud machine.”

Positive Outcomes

These interviews support the previous evidence that patients who experience greater improvements in daily functions have better PAP adherence.43 Indeed, these interviews suggest that patients who experience positive results using the PAP machine—“I woke up and felt like a different person”—are more likely to stick with it—“I don’t want to be without it.”

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to engage patients with a new diagnosis of OSA and their caregivers in a multifaceted experience that includes an educational session, hands-on experience, peer coaching session, and a semistructured one-on-two motivational interview. In our study, women constituted 57% of the study participants, which is in contrast to other reported studies in which the majority of participants are men.30,44–47 Our findings are similar to those of Luyster et al,30 which supported the inclusion of one’s spouse or partner in the new continuous PAP adherence program but different in many ways that our intervention brought together the patient with their caregiver (spouse, another family member, friend) for a systematic and a multifaceted intervention that included a peer coaching session, patient and caregiver were interviewed at the end of the in-person educational intervention and the patient-centered motivational interviews were conducted privately to enhance their participation.

Although Ye et al48 conducted a joint interview of the couples and provide important insight into the experiences of the couples together; the analysis does not incorporate the intervention and hence the patient’s and partner’s experience in going through the educational experience was not captured.

Our pilot study of multifaceted experiences demonstrates several important aspects of OSA diagnosis and experience by the patient and caregiver that often go unrecognized. (1) Patients with OSA were undiagnosed by the physicians. In cases where patients were motivated to get self-checked even when their physician said everything “looked fine” or were referred by a specialist speaks to the fact that the physicians need to carefully listen to their patients and learn about sleep disorders and appropriate referral. (2) Patients’ attitudes differed in terms of OSA diagnosis. Patients were routinely counseled after the OSA diagnosis for improved PAP adherence with the main focus on the patient’s severity of OSA and being a risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes, whereas its effect on patient’s emotional health was often disregarded. (3) These patients already had received the education and counseling regarding the OSA and PAP by their providers and PAP supplier but few of them were still left with questions or had struggled with the PAP mask; such patients appreciated the opportunity to have a hands-on education session to practice wearing the mask and benefitted from it. (4) Patients felt supported and encouraged when they heard the stories from their peers.

We note that the physical activity and weight loss discussed in the educational session was mentioned less frequently during the interviews. Given that the average body mass index was 35 kg/m2, it is important to emphasize on the modification of lifestyle factors, including weight loss via physical activity using patient preference (eg, dancing, walking, gardening) and diet (eg, handouts of simple recipes for salads, the need to increase green leafy vegetables to help reduce oxidative stress from OSA) as patients may not know about the importance of these lifestyle factors.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. (1) In our study, 29% of patients reported depression and 25% reported anxiety. Future studies could look at the pre-post incidence of reported depression and anxiety using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and other measures. (2) This study did not assess health-related quality of life. Future studies might want to include SF-12 pre-intervention and post-intervention to assess changes in health-related quality of life over time. (3) Because the motivational interview was conducted as the last session of the group visit, we are unable to comment on the attitudes prior to the group visit. (4) There were very few minorities in our study, and very few that we could identify in the literature review.49,50 There is a need for researchers to develop culturally responsive PAP interventions to address sleep health equity. (5) In conjunction with testing adherence interventions, future research might also explore perspectives among peer coaches to better understand their motivations for involvement as well as their insights on how to improve intervention program processes and outcomes. (6) As a qualitative approach, our analyses are not generalizable to the broader population of OSA patients and should be considered along with broader, more definitive research. More novel adherence interventions based on qualitative outcomes are needed.

CONCLUSIONS

The study provides insight into the practicality as well as the utility of the multifaceted intervention involving caregivers in real life. Based on our qualitative analysis, we hypothesize that patients’ and caregivers’ positive experiences of PAP could be enhanced by a patient-centered interaction such as I-CAP and this could subsequently improve PAP adherence and long-term outcomes. Large-scale quantitative studies are needed to further determine the efficacy and the cost-effectiveness of such multifaceted intervention.

A patient-centered interaction supported by a social environment could play a pivotal role in providing a positive experience to PAP and that it is important to explicitly address patient and caregiver’s fears and concerns to further enhance use of PAP.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All the authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the Department of Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States. The study was funded by the Sparrow Health System/Michigan State University Center for Innovation and Research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the sleep laboratory technician, Mr. Samson Dejene, and our peer coach, Ms. Sandra Meyers, for their time and contribution to this project. We gratefully acknowledge Sparrow Hospital sleep laboratory staff for their help with patients’ recruitment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):1006–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gay P, Weaver T, Loube D, Iber C. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep. 2006;29(3):381–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonsignore MR, McNicholas WT, Montserrat JM, Eckel J. Adipose tissue in obesity and obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(3):746–767. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00047010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;107(20):2589–2594. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terán-Santos J, Jiménez-Gómez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents. Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(11):847–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):173–178. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan SU, Duran CA, Rahman H, Lekkala M, Saleem MA, Kaluski E. A meta-analysis of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(24):2291–2297. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett D, Wong K, Richards D, et al. Increasing adherence to obstructive sleep apnea treatment with a group social cognitive therapy treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1647–1654. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lettieri CJ, Walter RJ. Impact of group education on continuous positive airway pressure adherence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(6):537–541. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broström A, Fridlund B, Ulander M, Sunnergren O, Svanborg E, Nilsen P. A mixed method evaluation of a group-based educational programme for CPAP use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(1):173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Stepnowsky C, Hecht J, Borrelli B. Predicting treatment adherence in obstructive sleep apnea using principles of behavior change. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1(4):346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouloukaki I, Giannadaki K, Mermigkis C, et al. Intensive versus standard follow-up to improve continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1262–1274. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00021314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards D, Bartlett DJ, Wong K, Malouff J, Grunstein RR. Increased adherence to CPAP with a group cognitive behavioral treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep. 2007;30(5):635–640. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng T, Wang Y, Sun M, Chen B. Stage-matched intervention for adherence to CPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(2):791–801. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai AYK, Fong DYT, Lam JCM, Weaver TE, Ip MSM. The efficacy of a brief motivational enhancement education program on CPAP adherence in OSA: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2014;146(3):600–610. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Strand M, Millman RP, Borrelli B. Motivational enhancement to improve adherence to positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1655–1662. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aloia MS, Smith K, Arnedt JT, et al. Brief behavioral therapies reduce early positive airway pressure discontinuation rates in sleep apnea syndrome: preliminary findings. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5(2):89–104. doi: 10.1080/15402000701190549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen S, Smith SS, Oei TP, Douglas J. Motivational interviewing (MINT) improves continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) acceptance and adherence: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):151–163. doi: 10.1037/a0026302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damjanovic D, Fluck A, Bremer H, Muller-Quernheim J, Idzko M, Sorichter S. Compliance in sleep apnoea therapy: influence of home care support and pressure mode. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(4):804–811. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00023408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoy CJ, Vennelle M, Kingshott RN, Engleman HM, Douglas NJ. Can intensive support improve continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4 Pt 1):1096–1100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9808008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meurice JC, Ingrand P, Portier F, et al. A multicentre trial of education strategies at CPAP induction in the treatment of severe sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007;8(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparrow D, Aloia M, Demolles DA, Gottlieb DJ. A telemedicine intervention to improve adherence to continuous positive airway pressure: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2010;65(12):1061–1066. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.133215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuna ST, Shuttleworth D, Chi L, et al. Web-based access to positive airway pressure usage with or without an initial financial incentive improves treatment use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1229–1236. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron KG, Gunn HE, Czajkowski LA, Smith TW, Jones CR. Spousal involvement in CPAP: does pressure help? J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(2):147–153. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batool-Anwar S, Baldwin CM, Fass S, Quan SF. Role of spousal involvement in continuous positive airway pressure (cpap) adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(5):213–227. doi: 10.13175/swjpcc034-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luyster FS, Dunbar-Jacob J, Aloia MS, Martire LM, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ. Patient and partner experiences with obstructive sleep apnea and CPAP treatment: a qualitative analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;14(1):67–84. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2014.946597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luyster FS, Aloia MS, Buysse DJ, et al. A couples-oriented intervention for positive airway pressure therapy adherence: a pilot study of obstructive sleep apnea patients and their partners. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17(5):561–572. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2018.1425871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gentina TBS, Jounieaux F, Verkindre C, et al. Marital quality, partner’s engagement and continuous positive airway pressure adherence in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2019;55:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parthasarathy S, Wendel C, Haynes PL, Atwood C, Kuna S. A pilot study of CPAP adherence promotion by peer buddies with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(6):543–550. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grayson-Sneed KA, Smith SW, Smith RC. A research coding method for the basic patient-centered interview. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(3):518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dwamena FC, Fortin AH, Frankel RM, Smith RC. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elfström M, Karlsson S, Nilsen P, Fridlund B, Svanborg E, Broström A. Decisive situations affecting partners’ support to continuous positive airway pressure-treated patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a critical incident technique analysis of the initial treatment phase. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(3):228–239. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182189c34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen S, Smith S, Oei TP. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnoea sufferers: a theoretical approach to treatment adherence and intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(8):1355–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawyer AM, Deatrick JA, Kuna ST, Weaver TE. Differences in perceptions of the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy among adherers and nonadherers. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(7):873–892. doi: 10.1177/1049732310365502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells RD, Freedland KE, Carney RM, Duntley SP, Stepanski EJ. Adherence, reports of benefits, and depression among patients treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(5):449–454. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e318068b2f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida FR, Henrich N, Marra C, et al. Patient preferences and experiences of CPAP and oral appliances for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a qualitative analysis. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(2):659–666. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broström A, Nilsen P, Johansson P, et al. Putative facilitators and barriers for adherence to CPAP treatment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a qualitative content analysis. Sleep Med. 2010;11(2):126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawyer AM, Gooneratne NS, Marcus CL, Ofer D, Richards KC, Weaver TE. A systematic review of CPAP adherence across age groups: clinical and empiric insights for developing CPAP adherence interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15(6):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reishtein JL, Pack AI, Maislin G, et al. Sleepiness and relationships in obstructive sleep apnea. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):319–330. doi: 10.1080/01612840500503047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye L, Antonelli MT, Willis DG, Kayser K, Malhotra A, Patel SR. Couples’ experiences with continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a dyadic perspective. Sleep Health. 2017;3(5):362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallace DM, Shafazand S, Aloia MS, Wohlgemuth WK. The association of age, insomnia, and self-efficacy with continuous positive airway pressure adherence in black, white, and Hispanic U.S. Veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(9):885–895. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diaz-Abad M, Chatila W, Lammi MR, Swift I, D’Alonzo GE, Krachman SL. Determinants of CPAP adherence in Hispanics with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Disord. 2014;2014:878213. doi: 10.1155/2014/878213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]