Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is more common in patients with asthma, and inhaled corticosteroids may contribute to OSA pathogenesis in these patients. This study tested the effects of orally inhaled fluticasone propionate (FP) on extrinsic tongue muscles. Unanesthetized rats were treated with FP or placebo for 28 days. On day 29, tongue retrusive and protrusive functions were tested via hypoglossal nerve stimulation under a state of anesthesia, followed by genioglossus (GG), styloglossus (SG) and hyoglossus (HG) muscle extraction, after euthanasia, for histology [myosin heavy chain (MHC) fibers and laminin content reflecting extracellular matrix (ECM)]. On protrusive testing, FP increased percent maximum tetanic force at 40 Hz (P = 0.03 vs. placebo) and endurance index (P = 0.029 vs. placebo). On retrusive testing, FP increased maximum twitch (P = 0.026 vs. placebo) and tetanic forces (P = 0.02 vs. placebo) with no effect on endurance index. On histology, FP increased GG cross-sectional area of MHC type IIa (P = 0.036 vs. placebo) and tended to increase type IIb (P = 0.057 vs. placebo) fibers and HG MHC IIx fibers (P = 0.065). The FP group had significantly increased laminin-stained areas, of greatest magnitude in the HG muscle. FP affects tongue protrusive and retrusive functions differently, concurrent with a shift in MHC fibers and increased ECM accumulation. These differential alterations may destabilize the tongue’s “muscle hydrostat” during sleep and promote collapse.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The effects of inhaled corticosteroid on upper airway may contribute to OSA pathogenesis in asthma. In this study, we tested the effects of orally inhaled fluticasone propionate on tongue protrusive and retrusive functions and on tongue extrinsic muscle fiber composition and molecular properties. We found that fluticasone treatment: 1) increased protrusive endurance and retrusive maximum twitch and tetanic force; and 2) on histology, increased cross-sectional area of myosin heavy chain (MHC) type IIa fibers and tended to increase cross-sectional area of MHC type IIb fibers in the protrusive muscle and of MHC IIx fibers in the retrusors. It also increased laminin-stained areas, across extrinsic tongue muscles, of greatest magnitude in the retrusors; and 3) reduced protein degradation and activated pathways associated with increased protein synthesis in the protrusor. These differential effects on the protrusors and retrusors may destabilize the tongue’s “muscle hydrostat” properties during sleep and promote collapse.

Keywords: asthma, extrinsic tongue, fluticasone propionate, inhaled corticosteroids, obstructive sleep apnea

INTRODUCTION

Multiple studies found an increased predisposition for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in people with asthma (36). In epidemiological studies, individuals with asthma report snoring and witnessed apneas 1.7 (13, 17, 24) and 3.7 times (1) more often, respectively. Moreover, asthma is an independent risk factor for incident OSA (47). Additionally, in clinic-based studies, OSA is highly prevalent, in relationship to asthma severity (19), with ~88–95% of patients with severe asthma having OSA on polysomnography (19, 51). Conversely, OSA adversely impacts asthma, emphasizing the need to understand specific OSA pathophysiology in this population (36).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), the standard treatment for chronic-persistent asthma (15a), may contribute to the increased OSA risk in patients with asthma. In patients with asthma, ICS use is related with OSA risk in a dose-dependent fashion (48). This increased OSA risk may occur as a result of several established corticosteroid effects, which relate to well-known contributing pathways to OSA pathophysiology in general populations. These include weight gain/fat redistribution to the neck area leading to oropharyngeal crowding (28), chronic low-level chemical inflammation, as observed in the larynx (50); and water retention with rostral fluid shift to the neck at night (37). Another possibility relates to the known myopathic effect of corticosteroids, resulting from increased protein degradation (10), which is believed to underlie the ICS-induced dysphonia (50). Indeed, in a previous study, treatment with inhaled fluticasone propionate increased wakefulness tongue protrusive strength and decreased endurance. In contrast, the same study found that fluticasone propionate (FP), overall, decreased pharyngeal upper airway collapsibility during sleep, with variability in the response related to individual’s baseline characteristics (49). Similar wakefulness tongue protrusive physiology was reported in untreated OSA patients (11). On histopathology, a shift from type 1 (slow twitch-low force, fatigue resistant) to type 2 (fast twitch-high force, fatigue prone) fibers was found in uvula muscle, believed to be an adaptation to the increased contractile demands on the dilator (23).

Despite evidence for a paramount role of extrinsic tongue muscles in breathing (7, 15, 35), their physical location in the path of inhaled airflow, along with local oral deposition of a significant ICS fraction (38), detailed experimental studies on the effects of ICS on these muscles are lacking.

In this study, we aimed to test the effects of orally inhaled FP on tongue physiology and fiber composition in the protrusive [genioglossus (GG)] and retrusive [styloglossus (SG) and hyoglossus (HG)] tongue extrinsic muscles and begin evaluating potential underlying molecular mechanisms, such as protein degradation and regulation of protein synthesis via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. We hypothesized that FP will 1) increase protrusive maximum twitch and tetanic force while decreasing endurance; 2) decrease the proportion of slow twitch muscle fibers while increasing the proportion of fast twitch fibers, also reducing fiber cross-sectional area (CSA); and 3) increase protein degradation in the muscle.

METHODS

Procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee.

Materials and reagents.

Fluticasone Propionate Metered Dose Inhaler (MDI) HydroFluoroAlkane (HFA) (220 µg/puff) (GlaxoSmithKline, Raleigh, NC) was obtained from University of Wisconsin research pharmacy and placebo canisters containing the HFA propellant from H&T PressPart (Cary, NC). All other reagents, unless specified, were obtained through ThermoFischer Scientific.

Animals.

Fischer 344 x CDF (F1) 9-mo-old male rats (Envigo Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed one per cage and given ad libitum water and standard rat chow according to their treatment group.

Treatment groups and feeding.

At the start of the 28-day experiment, each rat was weighed and group allocation to either FP or placebo treatment was done in a weight-matched fashion groups (n = 10/group). Animals were provided with ad libitum food and water. In an attempt to control for the steroid-induced anorexia and weight loss reported in rats treated with systemic corticosteroids (26), a food-restricted (FR) group was added. As detailed in the discussion, we concluded that FR was not an appropriate control, since FR itself induces a stress response consisting of an increase in endogenously secreted steroids (16), confounding the effects of our steroid-based experimental treatment. Thus details about the methods and results with comparisons between FR versus FP and FR versus placebo are presented in the online Supplemental Materials (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9789230).

An additional set of six rats were later added to each group, to account for subject loss during the course of the experiment or damage to the hypoglossal nerve during end point. A seventh rat was added to the placebo group, as in this group we were unable to obtain adequate data in more subjects. These additional rats were again weight matched. Rat losses were not unusual due to the delicate nature of the hypoglossal nerve stimulation surgery and were not a result of the experimental FP treatment.

Rats were dosed twice daily (between 0800 and 1000 h and between 1600 and 1800 h, local time), for 28 days. Unanesthetized rats were lightly restrained. The mouthpiece of a modified human MDI device, outfitted with a 13-G oral gavage needle, was inserted into the oral cavity, 3–5 mm posterior to the mesial incisors, and one puff of fluticasone propionate (FP) (220 μg/puff) or propellant placebo control, was delivered. An efficiency test revealed that the modified meter dose inhaler dispensed ~50% of the intended dose (110 μg/puff). Efficiency tests were done by spraying five puffs of FP onto a piece of sticky tape. Both the sticky tape and canister were weighed before and after the puffs were administered, and the amount of drug delivered are expressed in micrograms (29).

Tongue physiology testing.

On day 29, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane followed by intraperitoneal pentobarbital (0.1 ml/100 g), with an additional 0.05 mL injected before start of protrusive testing. Twitch, tetanic, and endurance physiologic measurements were obtained.

In brief, after anesthesia with pentobarbital, the hypoglossal nerve was exposed and stimulation electrodes were attached bilaterally on the hypoglossal nerve, which innervates muscles of the extrinsic tongue. The tongue was attached to a force transducer (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) via a suture and the nerve was stimulated at supramaximal levels, defined as 1.5 times the amplitude needed to induce maximal muscle contraction (usually between 300 and 500 µA). This allowed for the measurement of net retrusive force function. The stimulation signal and tongue force signal were acquired digitally on a dedicated laboratory computer equipped with an A/D converter (Data Translation, Marlboro, MA), using specialized data acquisition software (Acquire Ver. 1.3.0, Madison, WI). Maximum twitch measurements were taken first, along with twitch contraction time (time from stimulus to half-peak twitch force on the ascending contraction) and decay time (time from stimulus to half-peak twitch force on the descending contraction). Maximum tetanic force was then taken across increasing stimulation frequencies of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 Hz. Finally, endurance measurements were taken by measuring the percentage of force generated after 2 min of continuous stimulation (80 or 100 Hz) compared with the force at the start of the 2 min. The endurance index was calculated by dividing the force of the last measurement by the force of the first measurement and multiplying by 100, to obtain a percentage. After these measurements were taken, the lateral branch of the hypoglossal nerve was sectioned, allowing for the measurement of net protrusive force function. After a 45-min stabilization period, the same set of measurements was repeated. Further detail can be found in Ref. 41.

Rats were euthanized by intracardiac injection of pentobarbital/phenytoin (Euthasol; 0.2 mL/kg body wt). The GG, SG, and HG were extracted bilaterally followed by two hindlimb muscles, the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and soleus (SOL), to serve as controls for any systemic effects of the drug. For each pair of muscles, one was snap frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound for histology and the other was snap frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen and used for molecular analyses. All samples were stored at −80°C.

Immunofluorescent staining for myosin heavy chain isoforms and laminin.

Four 10-μm-thick transverse cross-sections were cut from the medial portion of individual muscle samples using a cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) and placed onto positively charged slides. The sections were then immunofluorescently stained based on an optimized version of a previous described method (8). In brief, sections were fixed in cold acetone (4°C) for 10 min. Sections were then circled with a liquid blocker pen, and slides were washed twice for 2 min with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Slides were then incubated in 1× PBS, 10% normal goat serum (NGS) blocker for 30–45 min. Next, the slides were drained/blotted and incubated overnight with primary antibodies in 10% NGS blocker, at 4°C. Primary antibody cocktails consisted of either SC-71 and BF-F3 antibodies [staining for myosin heavy chain (MHC) IIa and MHC IIb fiber types, respectively] or BA-F8 and 6H1 antibodies (staining for MHC I and MHC IIx fiber types, respectively) at a concentration of 1:6. Primary antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa). A concentration of 1:500 was used for primary laminin (L9393; Sigma-Aldrich). The next day, slides were drained and washed three times for 5 min with 1× PBS, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies in 10% NGS blocker for 45 min, at room temperature. This step, as well as all following steps, was performed without light, as these secondary antibodies were immunofluorescent. Secondary antibody cocktails consisted of either Alexa Fluor (AF) 350 anti-mouse IgG1 and AF555 anti-mouse IgM antibodies (staining for MHC IIa and MHC IIb/IIx fiber types, respectively) or AF350 anti-mouse IgG2b and AF555 anti-mouse IgM antibodies (staining for MHC I and MHC IIb/IIx fiber types, respectively) at a concentration of 1:200. Both cocktails also contained 1:500 AF488 anti-rabbit IgG for laminin. All secondary antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Slides were then drained and washed three times for 5 min with 1× PBS and allowed to air dry before coverslipping with a Prolong AntiFade Gold mounting media.

Muscle fiber typing and CSA.

A representative image from each slide was chosen and scanned at ×20 magnification using an Evos Microscope. This scan was then used for SMASH analysis (45). In brief, scanned images were loaded into the program. The program then outlined muscle fibers using the laminin stain. Laminin is a part of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which constitutes muscle fiber borders. This initial segmentation step produced a fiber mask. Muscle fiber parameters, such as minimum and maximum fiber area, maximum eccentricity, and maximum convexity, were then set and small segments in interstitial space were filtered out. Muscles properties, such as minimum and maximum fiber diameter and fiber CSA, were then exported into an Excel file. Fiber typing analysis was then performed by selecting the color of the stained MHC fiber type of interest and setting a light intensity threshold. Any fiber below this threshold was excluded from analysis. Any fiber above the threshold was analyzed, and its characteristics (mean fiber size, fiber intensity, individual fiber CSA), as well as the positive percent composition of the fiber type of interest among all fibers in the section, were exported into an excel file. More detail can be found in Ref. 45. The SMASH analyses were done by a single investigator (C. Setzke), to ensure consistency.

Laminin content analysis.

Scanned images were uploaded into ImageJ (40). They were then separated in their individual red, blue, and green channels, and the channel stained for laminin was used for further analysis. This channel was converted to binary so that all positively stained pixels would be displayed at the maximum intensity, and any nonstained pixels were displayed at the minimum intensity. The muscle section was then outlined using the freehand tool, excluding stained area outside the main section, which may be other laminin-stained components that do not constitute muscle ECM laminin. The measurement threshold was set so that only maximum intensity pixels would be analyzed, and a percent area occupied by the maximum intensity pixels was computed. This gave the percentage of the outlined section that was positively stained for laminin.

Glutamine synthetase activity.

A glutamine synthetase activity assay kit (MyBiosource, San Diego, CA) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions to assess protein degradation. The GG and EDL were selected for this analysis due to significant results in MHC fiber composition found on SMASH analysis.

mTORC activity.

We measured the activity of the following mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) downstream signaling targets in the GG tissue: 1) ribosomal protein S6 (S6); 2) 40S ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K1); 3) 4E-binding protein 1(4E-BP1); and 4) unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) and the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) downstream signaling target protein kinase B (AKT), using our published methods (3, 53). In brief, samples were lysed in cold RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets. They were lysed using a FastPrep 24 (M.P. Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) with bead-beating tubes and ceramic beads (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and then centrifuged for 10 min at 13,300 rpm at 4°C. Samples (20 μg total protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% (weight/volume) nonfat dry milk (NFDM) in 1× TBS-Tween20, for 20 min at room temperature and incubated overnight on a rotator at 4°C, in a cold dark room, with the following specific primary antibodies at a 1:1,000 concentration: p-T37/S46 4E-BP1 (2855), 4E-BP1 (9644), p-S240/S244 S6 (2215), S6 (2217), p-S473 AKT (4060), AKT (4691), p-T389 S6K1 (9234), S6K1(2708), p-S757 ULK1 (14202), and ULK1 (8054). Antibodies were diluted in 1xTBST with 5% NFDM or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for antibodies specific to phospho-proteins. The next day, the membrane was washed with 1× TBS-Tween20 and then incubated at room temperature with Anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked antibody (7074) at 1:2,000 concentration. All antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Membranes were developed using Pierce Enhanced Chemiluminescence Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) and Amersham Enhanced Chemiluminescence Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Images (16-bit TIF files) were acquired using GE ImageQuant LAS 4000 station. Quantification was performed by densitometry using NIH ImageJ software.

Statistics.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Due to significant body weight changes, on physiology testing, maximum twitch and tetanic measurements were normalized to body weight, as previous literature recommends (18). All graphing and analyses were performed using Prizm Software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Two-group, one-variable comparisons were made with t tests (unpaired test), and two-group, two-variable comparisons assessing effects in time on food consumption and weight were made with repeated measures ANOVA models (two-way). Post hoc Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used to compare group means for ANOVA analyses. All data analyzed conformed to parametric assumptions. Results with P < 0.05 were considered to be significant, and those with P = 0.05–0.10 were considered trends.

RESULTS

Because ICS may induce pharyngeal upper airway dysfunction and predispose to the heightened OSA risk observed in patients with asthma, in this study, we tested the effects of 28-day, twice daily, orally inhaled FP versus placebo administration on extrinsic tongue muscles’ physiological, histological, and molecular properties, in weight-matched rats.

Weight and food consumption.

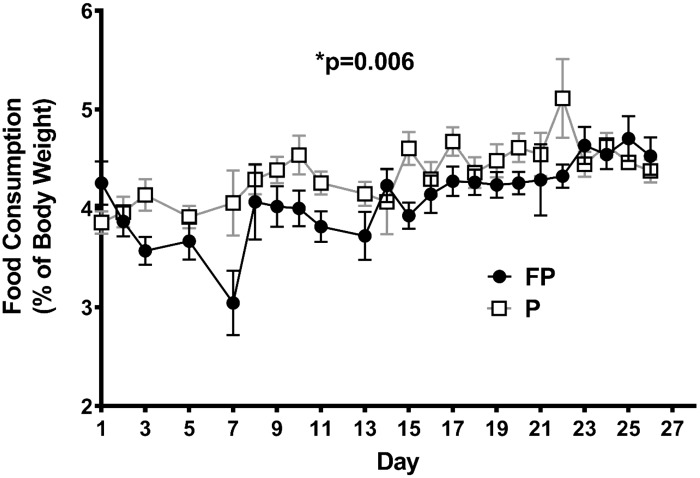

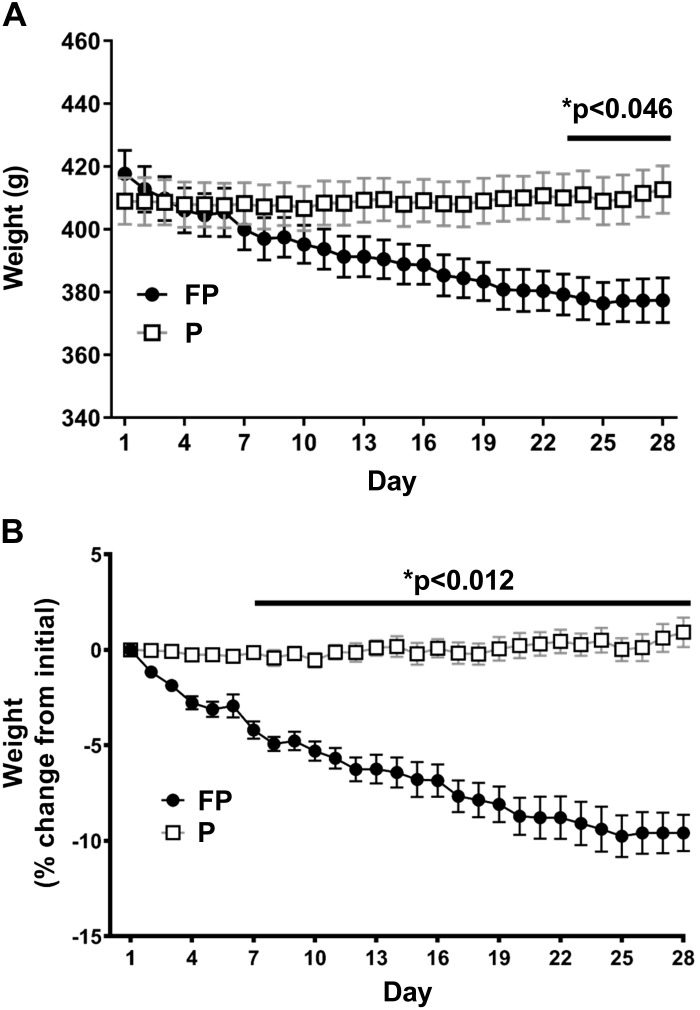

Food consumption as percentage of body weight was significantly lower in the FP than in the placebo group (P = 0.006) (Fig. 1). Body weights in the FP group dropped significantly over time (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Starting on day 23, the FP group had significantly lower body weights than the placebo group (P < 0.046 for days 23–28). Similarly, there was a significant interaction between time and experimental treatment (P < 0.0001) on percent weight loss (repeated measures two-way ANOVA; Fig. 2B), such that after day 7, FP-treated had lost significantly more percentage from initial weight than placebo-treated rats (P < 0.012 for days 7–28). This decrease in weight with FP is similar to previous studies using intraperitoneal injections of hydrocortisone sodium succinate (26). Interestingly, in the final days of our experiment, the FP-treated rats’ weight loss stabilized.

Fig. 1.

Food consumption as percentage of body weight. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either fluticasone propionate (FP) or placebo propeller inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food, and their food consumption was measured daily. FP compared with placebo-treated animals had an overall lower food consumption as %body weight (P = 0.006). Two-way ANOVA analysis and Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significant difference (exact values are shown); n = 14–16 rats/group.

Fig. 2.

Fluticasone propionate (FP) treatment led to significant weight loss. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with FP or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food. Rat weight was measured daily. A: rat weight: compared with placebo, FP-treated animals had significantly lower body weights on days 23–28 (P < 0.046). B: percent weight change from start of experimental treatment: FP had lost significantly more percent of their initial body weight than placebo (days 7–28) (P < 0.012). Two-way ANOVA analysis and Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significant difference (exact values are shown); n = 14–16 rats/group.

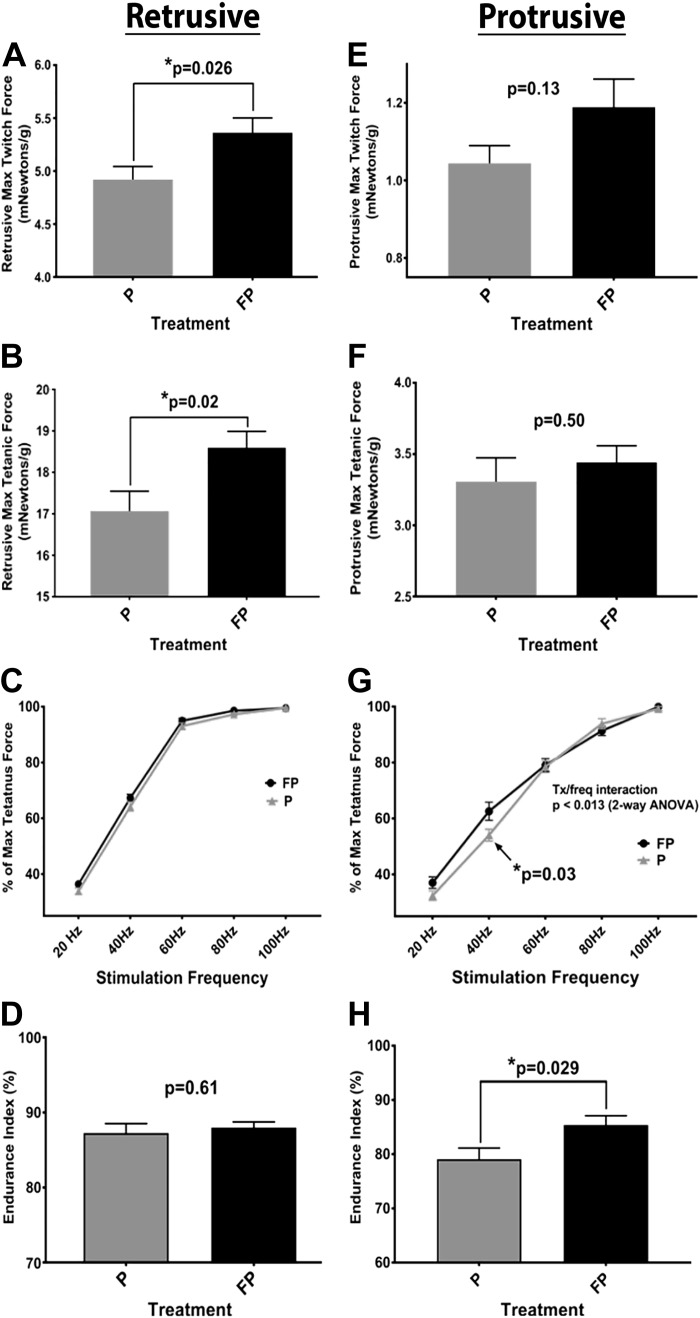

Retrusive physiology.

FP increased maximum twitch force compared with placebo (P = 0.026) (Fig. 3A). There were no significant differences in either contraction or decay time. FP increased the maximum tetanic force (P = 0.02) (Fig. 3B). FP had no effect on percent maximum tetanic force at any frequency (Fig. 3C). No significant treatment effect was noted in endurance index (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Differential effects of fluticasone propionate (FP) on retrusive and protrusive tongue functions. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either FP or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food. On day 29, retrusive and protrusive physiological outcomes were collected, measured using hypoglossal nerve stimulation. Measurements included maximum twitch and tetanic force (at varying stimulation frequencies), as well as endurance index (see methods). A: FP treatment showed an increase in maximum retrusive twitch force, compared with placebo, when normalized for weight (P = 0.026). B: FP treatment increased maximum retrusive tetanic force (P = 0.02). C: no significant effect of treatment was noted in the retrusive %maximum tetanic force at any frequency. D: no significant effect of treatment was noted in the retrusive endurance index. E: there was no significant effect of treatment on maximum protrusive twitch force. F: there was no effect of treatment on maximum protrusive tetanic force. G: FP-treated animals exhibited a significantly higher %maximum protrusive tetanus force at stimulation frequency 40 Hz compared with placebo (P = 0.03). H: FP animals had significantly higher protrusive endurance than the placebo treatment group (P = 0.029). Unpaired t test was used for A, B, D, E, F, and H. Two-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests were used for C and G. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significant difference (exact values are shown); n = 10–16 rats/group.

Protrusive physiology.

There was no significant effect of treatment on maximum protrusive twitch force (Fig. 3E). No significant differences were found between the treatments in twitch contraction or decay time. There was no effect of treatment on maximum tetanic force (Fig. 3F). FP-treated animals exhibited a higher percentage of maximum tetanus force at stimulation frequency of 40 Hz versus placebo (P = 0.03) (Fig. 3G). FP animals had higher protrusive endurance index than the placebo group (P = 0.029) (Fig. 3H).

Extrinsic tongue and hindlimb muscle composition.

In the GG, SG, and HG, there were no significant differences in fiber type percent composition, for any MHC isoforms. In the EDL and SOL, there were no significant differences in the fiber type percent composition for any MHC isoforms.

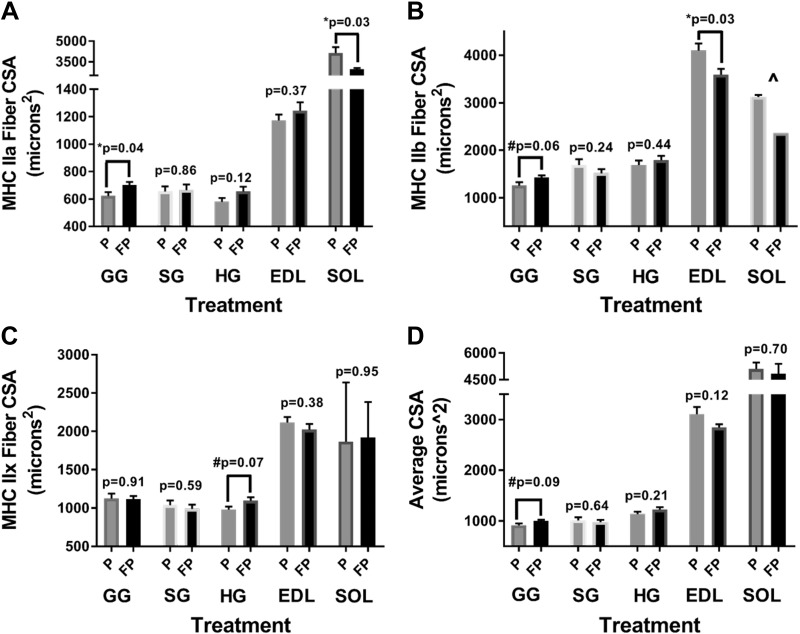

Extrinsic tongue muscle fiber CSA.

In the GG, in FP compared with placebo-treated rats, there was a significant increase in MHC type IIa fibers CSA (P = 0.036) (Fig. 4A) and a trend for increased type IIb CSA (P = 0.057) (Fig. 4B); there was also a trend for increased average overall fibers’ CSA (P = 0.087) (Fig. 4D). In the HG, in FP compared with placebo-treated rats, there was a trend for increased type IIx CSA (P = 0.065) (Fig. 4C). In the SG, in FP compared with placebo group, there were no significant differences in the CSA of any fiber isoforms.

Fig. 4.

Extrinsic tongue and skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain (MHC) fiber cross-sectional area (CSA). Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either fluticasone propionate (FP) or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food. On day 29, after physiological outcomes were collected, the extrinsic tongue as well as hindlimb muscles were harvested for histological analyses of MHC fibers (see methods). A: in the genioglossus (GG), there was a significant increase in MHC type IIa fiber CSA with FP compared with placebo treatment (P = 0.04). B: in the GG, FP compared with placebo treatment tended to increase MHC type IIb fiber CSA (P = 0.06). In the extensor digitorum longus (EDL), there was a significant decrease in MHC type IIb fiber CSA in FP compared with placebo treatment (P = 0.03). C: in the hyoglossus (HG), FP tended to increase MHC type IIx fiber CSA compared with placebo (P = 0.07). D: in the GG, FP tended to increase average fiber CSA compared with placebo (P = 0.09). No significant difference was found for styloglossus (SG) in A, B, C, or D. An unpaired t test was used. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, #0.1 < P < 0.05, significant difference (exact values are shown); n = 5–10 rats/group. ^There was an insufficient number of IIb fibers in the soleus (SOL) to perform a t test.

Hindlimb muscle fiber CSA.

In the EDL, in FP compared with placebo-treated rats, there was a decreased MHC type IIb CSA (P = 0.025) (Fig. 4B); there were no significant differences for type I, IIa, or IIx CSA. In the SOL, in FP compared with placebo group, we noted decreased type IIa CSA (P = 0.028) (Fig. 4A). There were no significant differences for any other fiber type.

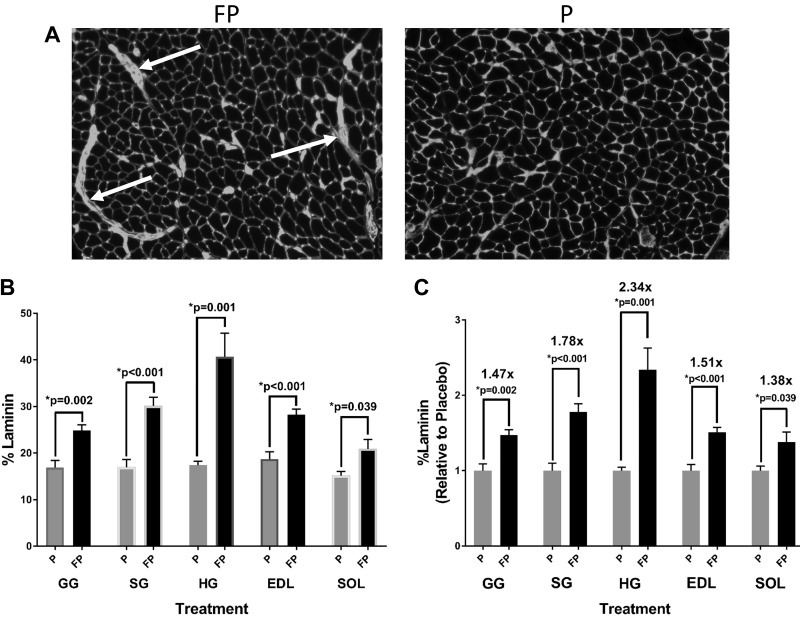

Content of laminin-stained areas.

During the fiber percent composition and CSA data collection, scattered areas of increased laminin accumulation were noted in FP-treated rats (see representative images in Fig. 5A). Quantitatively, FP versus placebo significantly increased the percent amount of such areas in the GG (P = 0.002), SG (P < 0.001), HG (P = 0.001), EDL (P < 0.001), and SOL (P = 0.039) (Fig. 5B), with HG demonstrating the highest (2.3-fold vs. placebo) content (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Laminin-stained areas. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either fluticasone propionate (FP) or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food. On day 29, extrinsic tongue as well as hindlimb muscles were harvested for laminin staining (see methods). A: representative images showing increased laminin-stained areas in the genioglossus (white arrows pointing to areas of accumulation) in FP vs. placebo-treated rats. B: there was a significant increase in the percent amount of laminin in FP vs. placebo rats in the genioglossus (GG) (P = 0.002), styloglossus (SG) (P < 0.001), hyoglossus (HG) (P = 0.001), extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (P < 0.001), and soleus (SOL) (P = 0.039). C: there was a significant increase in relative laminin content, compared with placebo, in FP rats the GG (P = 0.002), SG (P < 0.001), HG (P = 0.001), EDL (P < 0.001), and SOL (P = 0.039). Numbers above P values represent fold increase with FP treatment compared with placebo for each muscle. Unpaired t test was used. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significant difference (exact values are shown); n = 5–6 rats/group.

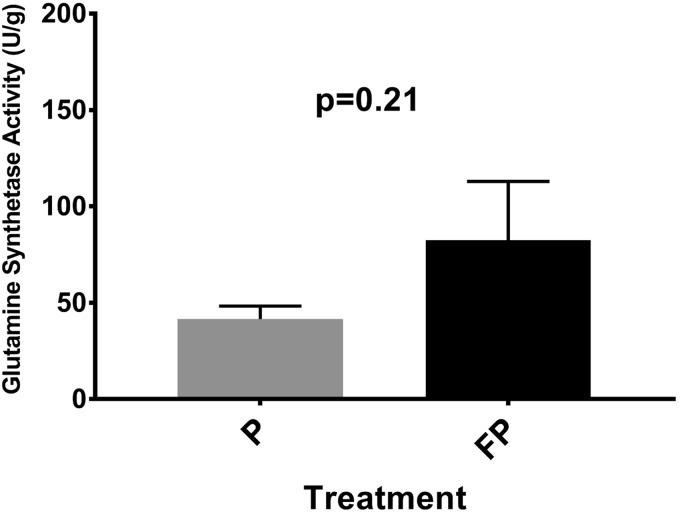

Glutamine synthetase activity.

In the GG and EDL, no significant effect of treatment in glutamine synthetase activity was found between the treatment groups (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Genioglossus (GG) glutamine synthetase activity. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either fluticasone propionate (FP) or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food and food consumption and rat weight was measured daily. On day 29, extrinsic tongue as well as hindlimb muscles were harvested for glutamine synthetase activity (see methods). In the GG, there was higher glutamine synthetase activity (denoting reduced protein degradation) in FP vs. placebo rats, although this was not statistically significant. Data are means ± SE; n = 8–10 rats/group.

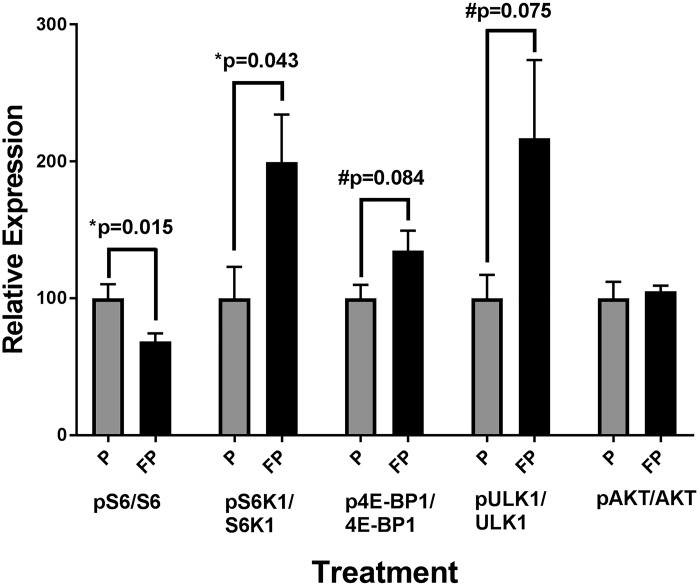

mTORC activity.

In the GG, in FP versus placebo rats, there was a significant decrease in the phosphorylation of the mTORC1 downstream readout S6 S240/S244 (P = 0.015), while there was a significant increase in the phosphorylation of the mTORC1 substrate S6K1 T389 (P = 0.043) (Fig. 7). We also noted a trend toward increased phosphorylation of the mTORC1 substrates 4E-BP1 T37/S46 (P = 0.084) and ULK1 S757 (P = 0.075) (Fig. 7). There was no significant difference in the phosphorylation of the mTORC2 substrate, AKT S473 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Genioglossus (GG) mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity. Weight-matched rats were treated twice daily, for 28 days, with either fluticasone propionate (FP) or placebo propellant inhaler (P). Rats were provided with ad libitum water and food. On day 29, extrinsic tongue as well as hindlimb muscles were harvested for assays of mTORC pathway targets (see methods). In the GG, there was a significant decrease in relative S6 activity in the FP vs. placebo rats. There was also a significant increase in S6K activity and a trend in increased 4E-binding protein 1(4E-BP1); and 4) unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) activity in FP vs. placebo animals. There was no significant difference in AKT activity. Data are means ± SE; n = 7–9 rats/group.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report corroborating physiologic, histologic, and molecular data on the effects of an orally inhaled corticosteroid on the extrinsic tongue muscles, which may be detrimental to key pharyngeal upper airway functions.

Physiological effects.

Our results show that FP affects protrusive and retrusive functions differently. That is, in contrast to our hypothesis, on protrusive testing FP increased endurance, while on retrusive testing it only increased maximum twitch and tetanic force measurements without an effect on endurance. The evolving field of hypoglossal stimulation for treatment of OSA has led to increased recognition that pharyngeal upper airway stability and patency requires coactivation of both protrusive and retrusive muscles in a very delicate balance during breathing, and particularly during sleep (13a, 15, 35). Specifically, activation of the tongue protrusors has different mechanical effects when it co-occurs with that of the retrusors. In anaesthetized rats, hypercapnic stimulation of protrusors alone, while it dilated the pharyngeal upper airway, it did not significantly decrease its collapsibility. In contrast, coactivation with the retrusors was superior in reducing the pharyngeal collapsibility (15). Furthermore, in humans, the activation pattern of these opposing muscle groups differs between sleep and wakefulness. That is, during wakefulness, resistive loading produced concomitant increases in both protrusor and retrusor activity. However, during sleep, resistive loading increased twofold the protrusor activity from the wake level, while retrusive muscles reached, on average, only approximately two-thirds of the wakefulness level (13a). Moreover, combined electrical stimulation of the GG and HG during sleep led to greater reductions in pharyngeal collapsibility than did stimulating the protrusor alone (35). These data suggest synergistic effects of these “antagonistic” muscle groups that stabilize airway patency during sleep. The differential FP-induced functional alterations in the two muscle groups may disturb the “muscle hydrostat” of the pharyngeal airway (13a, 46, 54), leading to “airway dyskinesia” and setting the stage for collapse during sleep.

Histological MHC fiber effects.

Our physiology results are further strengthened by the histological findings. Again, contrasting with our hypothesis, FP significantly increased MHC type IIa and tended to increase type IIb fiber CSA in the GG. GG is the main protrusive muscle, and type IIa fibers are relatively fatigue resistant (43, 54). These changes may explain the increased protrusive endurance, as well as the higher percentage of maximum tetanic force at lower stimulation frequencies. The trend for increased GG CSA of type IIb fibers, which are high force fibers, may explain the increase in protrusive max twitch force. The trend for an increase in type IIx fibers, also higher force fibers (43), in the HG, which is one of the extrinsic tongue retrusive muscles, may explain the increase in retrusive max twitch and tetanic forces.

While previous studies of systemic corticosteroid treatment showed selective atrophy of fast twitch (IIb/IIx) fibers in other muscles (5), the tongue muscles we studied do not show such changes. In fact, increased retrusive maximum twitch and tetanic forces argue against such effects. Furthermore, previous literature with systemic-administered formulations did not find an increased CSA of type IIa, IIb, or IIx fibers (5), as we found partly in our study. This study specifically tested effects of orally inhaled, as opposed to systemically administered (injected or swallowed), corticosteroids on skeletal muscles. This difference in drug delivery is very important, because only ~10–20% of the ICS actually reaches the lungs and most of the drug is either swallowed (and absorbed to be metabolized in the liver) or deposited on the upper airway structures, since FP is highly lipophilic and “sticky” (38). This local effect, as supposed to the systemic effect, may culminate in different local muscle morphological changes. Local effects on the upper airway are known from the ICS side-effects profile, including vocal cords adductors myopathy believed to underlie dysphonia (39). Interestingly, tongue hypertrophy was also reported with ICS use and resolved when switching to systemic treatment (25). This report is similar to our findings that show significant hypertrophy in the GG CSA of IIa fibers and trends for GG CSA of IIb and HG CSA of IIx fibers. This earlier report provides more support for differential local and systemic effects of corticosteroids on the muscle. The mechanisms underlying the local effects on MHC fibers changes, however, remain unknown but call for further investigations.

In contrast with GG and HG fiber hypertrophy, our findings of fast-twitch fiber atrophy in the EDL are consistent with published literature with systemic corticosteroids (5) and provide further evidence for differential local and systemic effects of FP. It has also been shown that SOL endurance and muscle mass decrease after prolonged systemic corticosteroid therapy (42), and the decrease we observed in type IIa fiber CSA in the SOL is consistent with those reports.

FP effects on laminin.

An increase in laminin-positive areas was found in both extrinsic tongue and hindlimb muscles, in FP compared with placebo rats. Among tongue muscles, the retrusors appear to be the most affected with the HG demonstrating the highest (2.3-fold vs. placebo) response. Laminin is a glycoprotein component of ECM. It is possible that ECM accumulation could impact the uniform contraction of the muscle and the ability to sustain a contraction. This may explain why in the retrusors we failed to see an increase in the endurance index, as we observed in the GG. Previous studies have found that potent systemic corticosteroids increase the concentration of collagen type IV and fibronectin in skeletal muscle, both of which are also components of ECM (1, 34), through a decrease in collagen-degrading enzyme activity (34). While our antibody staining targeted only laminin, it has been shown that laminin colocalizes with collagen type IV (33), leading us to believe there may also be other increased components of the ECM in these muscles.

Glutamine synthetase activity.

Glutamine is an amino acid that serves as a source of amide nitrogen, for the biosynthesis of amino acids that are used in protein formation (31). Increased glutamine metabolism may decrease free glutamine present in the muscle. It has been shown that glutamine triggers degradation of glutamine synthetase (49a), so higher protein formation in muscle would lead to decreased glutamine concentration and higher glutamine synthetase activity.

The GG physiologic and histologic findings align well with results of glutamine synthetase assay, where although not statistically significant, the glutamine synthetase activity appeared to be increased, on average, in FP- versus placebo-treated animals (mean FP = 82.38 versus P = 41.6 U/g). In contrast to our hypothesis, this finding points to reduced protein degradation and would further explain the fiber hypertrophy in the GG. The lack of statistical significance of this finding could be related to the much higher variation observed in the activity level of FP-treated rats compared with placebo [FP (SE) = 30.57 and P = 6.74]. One explanation for this finding may be that when running this assay, we randomly used either the posterior or anterior portions of the GG. However, it is possible that one part of the muscle, perhaps the posterior, is more in the path of airflow and vulnerable to local deposition, leading to the larger variability observed in this group. We believe this finding provides further support for a local effect of FP and is consistent with the increase in muscle fiber CSA we observed in the GG.

mTORC activity.

The mTORC1 complex directly regulates protein synthesis in mammals (20), through several pathways, among others: 1) signal transduction-mediated phosphorylation of different promotors, such as S6K1, and of inhibitors, such as 4E-BP1 (27); and 2) inhibition of autophagy, through phosphorylation of ULK1 (21). In our study, we found increased phosphorylation of S6K1, 4E-BP1, and ULK1 in the GG of FP- versus placebo-treated rats. These observations point to increased mTORC1 activity in the GG and increased protein synthesis, which complement the increase in fiber CSA we found on histology, and all together may reflect muscle fiber hypertrophy. Interestingly, previous studies have shown systemic corticosteroid administration to decrease mTORC1 activity in peripheral skeletal muscle through targeting the mTORC1 inhibitors, such as regulated in development and DNA damage response 1 (REDD1) and Kruppel-like factor 15, as well as the promotion of myostatin, which decreases mTORC1 effectors, such as S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (52). This difference in previous literature, once again, supports the notion of a local versus systemic effect of the drug. Interestingly, there was decreased phosphorylation in ribosomal protein S6, which is a downstream readout of mTORC1 activity (20). While S6 is phosphorylated by S6K1, one possible explanation for its decreased activity is that S6 phosphorylation is also influenced by other kinases and phosphatases, as well.

The role of food restriction.

In our attempt to control for steroid-induced anorexia and weight loss, we introduced the FR group. In this group, in the tongue muscles, we observed similar (lack of changes in any fiber type in the GG) and dissimilar (lack of changes in CSA of GG type IIa and IIb or different patter in SG IIb fibers) histologic findings than in the FP group (see online Supplemental Materials). In the hindlimb muscles, the main effect (content of laminin areas) was similar (see online Supplemental Materials). While we do not know underlying reasons for these divergent results, there may be several explanations. It is known that food restriction in rats induces a stress response manifested as an increase in the endogenously secreted steroids (16), which in turn could have caused similar effects and attenuated some of the differences noted with FP. This increase in endogenous steroids may explain the increase in laminin that also occurred in FR versus placebo rats but not as extreme as in FP rats, which received large doses of exogenous steroid. While the steroid induced anorexia indeed occurs, the increase in endogenous steroid resulting from food restriction brings into question the utility of FR as a comparison group when modeling corticosteroid effects, as others have also acknowledged (42). Even though some of the results seen in FP-treated rats may be due to decreased food consumption and weight loss, as we saw in FR rats, many results between these groups are different, and others, such as the increase in laminin, differ drastically in their magnitude. This leads us to believe that while changes in weight may have an impact, they contribute only in part to the overall FP outcomes.

Different patterns of eating may also have affected our results. FR rats rapidly consumed their food, whereas FP- and placebo-treated animals consumed their food throughout the day. FR animals also ate all food during light hours, which is when rats typically sleep. Taken together, this disturbed and misaligned pattern of eating with sleep and circadian rhythms could lead to hormone imbalance and metabolic derangements (22, 30) that may impact the muscles’ properties as well.

Limitations.

Our study has several limitations. First, the FP dose given relative to the body mass was higher than that a patient with asthma would receive. However, since we anticipated some drug will be lost with our delivery system, we chose the higher dose to still allow a large enough residual dose to be delivered. Should we have used a smaller dose and observed no effects, we would have questioned whether there was sufficient drug delivered to produce an effect. Starting out with a high dose in anticipation of possible imperfect delivery was our rationale, as it is in any novel model. A high starting dose was especially important, as we also did not know the fraction of drug that was to be swallowed versus inhaled distally versus locally deposited in the oral cavity. Nevertheless, further experimental studies are necessary to assess whether FP affects the tongue muscles in a dose-dependent manner, as one clinical-epidemiological study suggested (48). Second, the design was limited to one set of physiological end points, due to the invasive nature of the end point procedures. This did not allow us to see how tongue physiology changes over time and which muscle functions change first or track along. Methods involving hypoglossal stimulation in live rats over the course of the experiment (6) would allow us to see the evolution of these changes. While current in vivo technology would not allow testing of protrusive function, it would allow us to see how retrusive function changes over time. Third, our study only focused on the extrinsic tongue. There is evidence that the intrinsic muscles also play a role in breathing (4). Future studies need to account for the intrinsic functionality, as well as other upper airway muscle groups that are not innervated by the hypoglossal nerve. Fourth, we only looked at the effect of ICS on muscle fiber properties. Systemic corticosteroids have an effect on neuromuscular junction morphology and rate of failure, which in turn affect physiology of the muscle (44). It will be important in future studies to account for alternations in neuromuscular junctions and their impact on muscle physiology. One other limitation is that we were unable to correlate our findings with upper airway behaviors during important functions, such as sleep or swallowing. Future studies will need to be conducted to assess these in detail. Last, our methodology used a maximal muscle stimulation paradigm. This level of stimulation activated all MHC fiber types. In the diaphragm, it was shown that only slow twitch MHC fiber types (I/IIa) are recruited during tidal breathing, while fast twitch (IIb/IIx) fibers are recruited only during high ventilatory demands, such as coughing or sneezing, using varying levels of motor unit discharge frequency (14). To our knowledge, no studies have examined the pattern of MHC fiber recruitment in the tongue muscles during breathing. Without this knowledge, it remains unknown whether experiments using maximal stimulation provide a full insight into the extrinsic tongue physiology during breathing and sleep.

Summary.

In summary, FP affected the protrusive and retrusive properties of the tongue muscle groups differently, concurrent with histologic and biochemical changes, potentially leading to pharyngeal “airway dyskinesia.” This could leave the pharyngeal upper airway more susceptible to collapse and may explain the higher prevalence of OSA in people with asthma. We propose these tongue muscle changes relate to combined local and systemic effects, which explain the differences from other muscles in previous studies that used solely systemic formulations. These changes are not only important to breathing but to all functions involving the extrinsic tongue muscles, such as swallowing (12). This study emphasizes a critical need for investigations into the effect of ICS on key pharyngeal upper airway functions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Defense, U. S. Army Medical Research and Development Command Award W81XWH-17-1-0252 (to M. Teodorescu). This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AG-056771 and AG-062328 (to D. W. Lamming), R01-DC-018071 and R0-1DC-008149 (to N. P. Connor), and R37-CA-225608 (to J. A. Russell). The laboratories of D. W. Lamming and M. Teodorescu are supported in part by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Grant I01-BX004031, and this work was supported using facilities and resources from the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital.

DISCLAIMERS

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Government.

DISCLOSURES

D. W. Lamming has received funding from, and is a scientific advisory board member of, Aeovian Pharmaceuticals, which seeks to develop novel, selective mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors for the treatment of various diseases. M. Teodorescu has received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for an Investigator Initiated Project unrelated to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

O.B., J.A.R., N.P.C., and M.T. conceived and designed research; C.S., O.B., J.A.R., N.M., and M.S. performed experiments; C.S., O.B., J.A.R., N.M., M.S., D.W.L., and M.T. analyzed data; C.S., O.B., J.A.R., M.S., D.W.L., N.P.C., and M.T. interpreted results of experiments; C.S., O.B., and M.T. prepared figures; C.S. drafted manuscript; C.S., O.B., J.A.R., M.S., D.W.L., N.P.C., and M.T. edited and revised manuscript; C.S., O.B., J.A.R., M.S., D.W.L., N.P.C., and M.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Gary Sieck and his laboratory from Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) for initial guidance on implementation of myosin heavy chain isoform methodology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahtikoski AM, Riso EM, Koskinen SO, Risteli J, Takala TE. Regulation of type IV collagen gene expression and degradation in fast and slow muscles during dexamethasone treatment and exercise. Pflugers Arch 448: 123–130, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baar EL, Carbajal KA, Ong IM, Lamming DW. Sex- and tissue-specific changes in mTOR signaling with age in C57BL/6J mice. Aging Cell 15: 155–166, 2016. doi: 10.1111/acel.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey EF, Fregosi RF. Coordination of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles during spontaneous breathing in the rat. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 440–449, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00733.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodine SC, Furlow JD. Glucocorticoids and Skeletal Muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol 872: 145–176, 2015. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2895-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor NP, Russell JA, Jackson MA, Kletzien H, Wang H, Schaser AJ, Leverson GE, Zealear DL. Tongue muscle plasticity following hypoglossal nerve stimulation in aged rats. Muscle Nerve 47: 230–240, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mus.23499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cori JM, O’Donoghue FJ, Jordan AS. Sleeping tongue: current perspectives of genioglossus control in healthy individuals and patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Sci Sleep 10: 169–179, 2018. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S143296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullins MJ, Connor NP. Alterations of intrinsic tongue muscle properties with aging. Muscle Nerve 56: E119–E125, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mus.25605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekhuijzen PN, Decramer M. Steroid-induced myopathy and its significance to respiratory disease: a known disease rediscovered. Eur Respir J 5: 997–1003, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert DJ, Lo YL, Saboisky JP, Jordan AS, White DP, Malhotra A. Sensorimotor function of the upper-airway muscles and respiratory sensory processing in untreated obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985) 111: 1644–1653, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00653.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felton SM, Gaige TA, Reese TG, Wedeen VJ, Gilbert RJ. Mechanical basis for lingual deformation during the propulsive phase of swallowing as determined by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging. J Appl Physiol (1985) 103: 255–265, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01070.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick MF, Martin K, Fossey E, Shapiro CM, Elton RA, Douglas NJ. Snoring, asthma and sleep disturbance in Britain: a community-based survey. Eur Respir J 6: 531–535, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Fleury Curado T, Oliven A, Sennes LU, Polotsky VY, Eisele D, Schwartz AR. Neurostimulation Treatment of OSA. Chest 154: 1435–1447, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogarty MJ, Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Breathing: Motor Control of Diaphragm Muscle. Physiology (Bethesda) 33: 113–126, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller DD, Williams JS, Janssen PL, Fregosi RF. Effect of co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles on tongue movements and pharyngeal airflow mechanics in the rat. J Physiol 519: 601–613, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0601m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) (Online). https://ginasthma.org/ [2016]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Goldberg AL, Goldspink DF. Influence of food deprivation and adrenal steroids on DNA synthesis in various mammalian tissues. Am J Physiol 228: 310–317, 1975. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.1.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janson C, De Backer W, Gislason T, Plaschke P, Björnsson E, Hetta J, Kristbjarnarson H, Vermeire P, Boman G. Increased prevalence of sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness in subjects with bronchial asthma: a population study of young adults in three European countries. Eur Respir J 9: 2132–2138, 1996. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09102132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaric S. Role of body size in the relation between muscle strength and movement performance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 31: 8–12, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Julien JY, Martin JG, Ernst P, Olivenstein R, Hamid Q, Lemière C, Pepe C, Naor N, Olha A, Kimoff RJ. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea in severe versus moderate asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124: 371–376, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy BK, Lamming DW. The mechanistic target of rapamycin: the grand conductor of metabolism and aging. Cell Metab 23: 990–1003, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 13: 132–141, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TW, Jeong JH, Hong SC. The impact of sleep and circadian disturbance on hormones and metabolism. Int J Endocrinol 2015: 1–9, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/591729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimoff RJ. Upperairway myopathy is important in the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 3: 567–569, 2007. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsson LG, Lindberg A, Franklin KA, Lundbäck B. Symptoms related to obstructive sleep apnoea are common in subjects with asthma, chronic bronchitis and rhinitis in a general population. Respir Med 95: 423–429, 2001. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linder N, Kuint J, German B, Lubin D, Loewenthal R. Hypertrophy of the tongue associated with inhaled corticosteroid therapy in premature infants. J Pediatr 127: 651–653, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu XY, Shi JH, Du WH, Fan YP, Hu XL, Zhang CC, Xu HB, Miao YJ, Zhou HY, Xiang P, Chen FL. Glucocorticoids decrease body weight and food intake and inhibit appetite regulatory peptide expression in the hypothalamus of rats. Exp Ther Med 2: 977–984, 2011. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 307–318, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin RJ, Szefler SJ, Chinchilli VM, Kraft M, Dolovich M, Boushey HA, Cherniack RM, Craig TJ, Drazen JM, Fagan JK, Fahy JV, Fish JE, Ford JG, Israel E, Kunselman SJ, Lazarus SC, Lemanske RF Jr, Peters SP, Sorkness CA. Systemic effect comparisons of six inhaled corticosteroid preparations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 1377–1383, 2002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2105013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morel N, Broytman O, Martinez J, Teodorescu M. Development of an automated metered dose inhaler to deliver fluticasone to rats and examine the effects of corticosteroids on upper airway function and structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197: A4785, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris CJ, Purvis TE, Mistretta J, Scheer FA. Effects of the internal circadian system and circadian misalignment on glucose tolerance in chronic shift workers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101: 1066–1074, 2016. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neu J, Shenoy V, Chakrabarti R. Glutamine nutrition and metabolism: where do we go from here? FASEB J 10: 829–837, 1996. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ockleford C, Bright N, Hubbard A, D’Lacey C, Smith J, Gardiner L, Sheikh T, Albentosa M, Turtle K. Micro-trabeculae, macro-plaques or mini-basement membranes in human term fetal membranes? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 342: 121–136, 1993. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oikarinen A, Salo T, Ala-Kokko L, Tryggvason K. Dexamethasone modulates the metabolism of type IV collagen and fibronectin in human basement-membrane-forming fibrosarcoma (HT-1080) cells. Biochem J 245: 235–241, 1987. doi: 10.1042/bj2450235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliven A, Odeh M, Geitini L, Oliven R, Steinfeld U, Schwartz AR, Tov N. Effect of coactivation of tongue protrusor and retractor muscles on pharyngeal lumen and airflow in sleep apnea patients. J Appl Physiol (1985) 103: 1662–1668, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00620.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens RL, Macrea MM, Teodorescu M. The overlaps of asthma or COPD with OSA: A focused review. Respirology 22: 1073–1083, 2017. doi: 10.1111/resp.13107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perger E, Jutant EM, Redolfi S. Targeting volume overload and overnight rostral fluid shift: A new perspective to treat sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev 42: 160–170, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rees J. Methods of delivering drugs. BMJ 331: 504–506, 2005. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7515.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roland NJ, Bhalla RK, Earis J. The local side effects of inhaled corticosteroids: current understanding and review of the literature. Chest 126: 213–219, 2004. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, DeZonia BE, Walter AE, Arena ET, Eliceiri KW. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 18: 529, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1934-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell JA, Connor NP. Effects of age and radiation treatment on function of extrinsic tongue muscles. Radiat Oncol 9: 254, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0254-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasson L, Tarasiuk A, Heimer D, Bark H. Effect of dexamethasone on diaphragmatic and soleus muscle morphology and fatigability. Respir Physiol 85: 15–28, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(91)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev 91: 1447–1531, 2011. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sieck GC, Van Balkom RH, Prakash YS, Zhan WZ, Dekhuijzen PN. Corticosteroid effects on diaphragm neuromuscular junctions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 86: 114–122, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith LR, Barton ER. SMASH - semi-automatic muscle analysis using segmentation of histology: a MATLAB application. Skelet Muscle 4: 21, 2014. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sokoloff AJ. Activity of tongue muscles during respiration: it takes a village? J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 438–439, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01079.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teodorescu M, Barnet JH, Hagen EW, Palta M, Young TB, Peppard PE. Association between asthma and risk of developing obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA 313: 156–164, 2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teodorescu M, Consens FB, Bria WF, Coffey MJ, McMorris MS, Weatherwax KJ, Palmisano J, Senger CM, Ye Y, Kalbfleisch JD, Chervin RD. Predictors of habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea risk in patients with asthma. Chest 135: 1125–1132, 2009. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teodorescu M, Xie A, Sorkness CA, Robbins J, Reeder S, Gong Y, Fedie JE, Sexton A, Miller B, Huard T, Hind J, Bioty N, Peterson E, Kunselman SJ, Chinchilli VM, Soler X, Ramsdell J, Loredo J, Israel E, Eckert DJ, Malhotra A. Effects of inhaled fluticasone on upper airway during sleep and wakefulness in asthma: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med 10: 183–193, 2014. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Van Nguyen T, Lee JE, Sweredoski MJ, Yang SJ, Jeon SJ, Harrison JS, Yim JH, Lee SG, Handa H, Kuhlman B, Jeong JS, Reitsma JM, Park CS, Hess S, Deshaies RJ. Glutamine triggers acetylation-dependent degradation of glutamine synthetase via the thalidomide receptor cereblon. Mol Cell 61: 809–820, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams AJ, Baghat MS, Stableforth DE, Cayton RM, Shenoi PM, Skinner C. Dysphonia caused by inhaled steroids: recognition of a characteristic laryngeal abnormality. Thorax 38: 813–821, 1983. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.11.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yigla M, Tov N, Solomonov A, Rubin AH, Harlev D. Difficult-to-control asthma and obstructive sleep apnea. J Asthma 40: 865–871, 2003. doi: 10.1081/JAS-120023577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon MS. mTOR as a key regulator in maintaining skeletal muscle mass. Front Physiol 8: 788, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu D, Yang SE, Miller BR, Wisinski JA, Sherman DS, Brinkman JA, Tomasiewicz JL, Cummings NE, Kimple ME, Cryns VL, Lamming DW. Short-term methionine deprivation improves metabolic health via sexually dimorphic, mTORC1-independent mechanisms. FASEB J 32: 3471–3482, 2018. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701211R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaidi FN, Meadows P, Jacobowitz O, Davidson TM. Tongue anatomy and physiology, the scientific basis for a novel targeted neurostimulation system designed for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Neuromodulation 16: 376–386, 2013. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]