Abstract

Aortic aneurysm is a permanent focal dilation of the aorta. It is usually an asymptomatic disease but can lead to sudden death due to aortic rupture. Aortic aneurysm-related mortalities are estimated at ∼200,000 deaths per year worldwide. Because no pharmacological treatment has been found to be effective so far, surgical repair remains the only treatment for aortic aneurysm. Aortic aneurysm results from changes in the aortic wall structure due to loss of smooth muscle cells and degradation of the extracellular matrix and can form in different regions of the aorta. Research over the past decade has identified novel contributors to aneurysm formation and progression. The present review provides an overview of cellular and noncellular factors as well as enzymes that process extracellular matrix and regulate cellular functions (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases, granzymes, and cathepsins) in the context of aneurysm pathogenesis. An update of clinical trials focusing on therapeutic strategies to slow abdominal aortic aneurysm growth and efforts underway to develop effective pharmacological treatments is also provided.

Keywords: aortic aneurysm, aortic remodeling, proteases, smooth muscle cells

INTRODUCTION

Aortic aneurysm is a permanent localized dilation of the aorta thought to be caused by adverse remodeling of the aortic wall. The aortic wall consists of three layers: intima [endothelial cells (ECs) that line the aortic lumen], media [intermittent layers of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and elastin fibers], and adventitia (a network of fibrillar collagen and other matrix proteins and fibroblasts). Aortic aneurysms can form at any region along the aorta, including the ascending aorta, the arch, the aorta above the diaphragm, or below the diaphragm at supra- or infrarenal regions, and they are generally classified as thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) or abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) (Fig. 1). In an aneurysmal aorta, adverse structural remodeling is usually evident in all three layers of the aortic wall, but most prominent is degeneration of the medial layer due to degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and loss of SMCs (181). This leads to loss of compliance of the aortic wall, which is critical to its function of driving the blood flow in the arteries. It is well recognized that TAA and AAA are distinct pathologies with different initiating causes and likely mediated through different molecular mechanisms (100, 176, 177), but they also share a number of features. This review will focus on the general cellular and molecular events that can apply to both TAA and AAA while also clarifying any distinct differences.

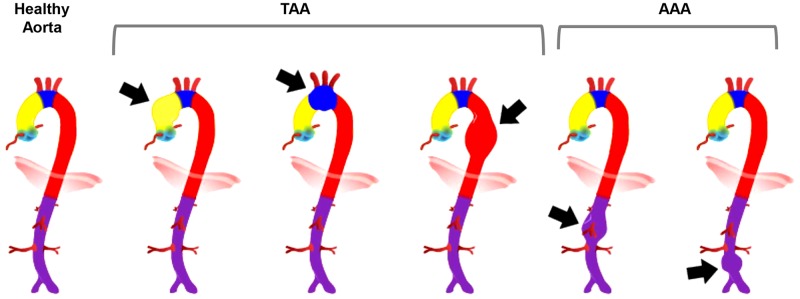

Fig. 1.

Aortic aneurysm can form in different regions along the aorta. Generally, if aneurysm is detected above the diaphragm it is referred to as thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA), and if below the diaphragm it is referred to as abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

AORTIC ANEURYSM AND THE ASSOCIATED RISK FACTORS

Aortic aneurysm can form in different regions of the aorta (Fig. 1). The prevalence of aortic aneurysm has decreased during the past two decades in the developed world, but in some regions, such as Latin America and high-income Asian-Pacific countries, it is increasing (183). Because aortic aneurysm is usually asymptomatic, its true prevalence is hard to determine, as ultrasound screening is not used worldwide. The prevalence of AAA varies in different sexes. Recent ultrasound screening studies report identifying AAA in 1–2% of 65-yr-old men and in 0.5% of 70-yr-old women (160, 183, 213). Women are underrepresented in most AAA studies. The outcomes of women with an AAA are worse than men. Women rupture at a smaller AAA diameter and have higher mortality rates following surgical repair (92, 93, 229, 233). A recent meta-analysis found that the 30-day mortality following either open or endovascular AAA repair was higher in women than in men (229). Interestingly, a recent study suggests that the lower percentage of AAA in women could be an artifact of differences in body size between men and women, since correction of the aortic diameter by body surface area revealed a much higher AAA prevalence in women than currently recognized, leaving only a modest sex difference (104). Although further validation of this finding may be needed, it is possible that AAA prevalence and severity in the female population has been underestimated.

Important risk factors for AAA include old age, smoking, family history of AAA, coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (71, 87, 103, 112, 121, 224). Interestingly, diabetes mellitus has been reported to inversely correlate with AAA (22), TAA (167), and aortic dissection (9). In a population study of more than 6,000 men and women in Tromsø, Norway, older age, smoking, low-serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), high plasma fibrinogen, and low platelet count were found to be associated with increased risk of AAA in both sexes, whereas high systolic blood pressure was a risk factor for AAA only in women (201). It is thought that quitting smoking significantly reduces the risk of AAA development (8). A study of Caucasians of Danish descent reported that smoking and male sex were the most important risk factors for aortic aneurysm (AAA or TAA) (204). This study reported that ex-smokers had a risk of developing aortic aneurysm similar to current smokers (204); however, the duration of smoking cessation was not taken into consideration. A long duration of smoking has been reported to be an important contributor to a high risk of developing an AAA (204, 250). Smoking may be a more important risk factor in women than in men, since it has been reported to stimulate premature menopause, and thus have negative effects on lipids through lowering HDL and increasing triglycerides (181, 233). Recent studies have also revealed that e-cigarettes share similar adverse effects to cigarette smoking in predisposing to vascular dysfunction and AAA (155, 156, 237).

AAA severity and post-surgery recovery have also been reported to vary in different ethnic groups. In a United States study, it was found that Hispanic ethnicity was associated with increased mortality after surgical repair of intact TAA, independent from preoperative comorbidities, postoperative complications, surgeon, or the hospital where surgery was performed (6). In a UK study, it was found that AAA was more common in Caucasian than black or Asian men (98). Other differences have been reported between distinct ethnic groups. Black Americans with an AAA have been reported to be younger and more often female compared with Caucasian or Asians (49). Black Americans have also been reported to more frequently develop renal failure following AAA repair than other races (49), whereas Asian people have been reported to have the highest rate of post AAA repair myocardial infarction (49). A screening study of New Zealand Maori men reported that the prevalence of AAA was higher than in Caucasian men (184). Among patients admitted to New Zealand hospitals with a diagnosis of AAA (1996–2007), Maori patients were found to be younger, with a higher mortality rate than European and Asian men, whereas Asian men and women had a significantly lower mortality rate than the European patients (185).

TAA is less prevalent than AAA, but the prognosis of TAA is worse, with the rate of rupture-associated mortality being higher than that for AAA patients (96, 107). Similar to AAA, TAA is more prevalent in men (161), and its prognosis is worse in women who are more likely to have an aortic dissection or rupture (47, 106). Female sex has also been significantly associated with greater aneurysm growth in patients with degenerative TAA, but not among those with heritable TAA (33). Furthermore, the mortality after elective endovascular repair of TAA has been reported to be higher in women than men, but this may be simply due to greater comorbidities in women (7). Unlike AAA, TAA can present at a young age due to the importance of monogenetic mutations in its etiology (141). TAA in young people usually has a familial or well-described genetic disorder such as Marfan syndrome (mutation in fibrillin 1), vascular Ehlers Danlos syndrome (mutations in collagens or collagen processing enzymes), or Loeys-Dietz syndrome [mutation in transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) receptor] (29, 66). Mutations in other ECM proteins have also been linked to TAA, including microfibril associated protein 5 (MFAP5) (11), lysyl oxidase (78, 123), and fibulin-4 (44). Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) has also been linked with TAA, but the gene responsible has not been identified (120). Inherited factors also play an important role in the etiology of AAA. The heritability of AAA has been reported to be ∼70% in a Swedish twin study (238). TAA occurs more often in the aortic root and ascending aorta (60%) than in descending aorta (40%) (95). Aortic aneurysms can also develop in multiple locations in the aorta of the same patient. About 20% of patients presenting with a large TAA also have an AAA, and some patients have aneurysms at multiple sites (77).

Different Morphologies of Aortic Aneurysm

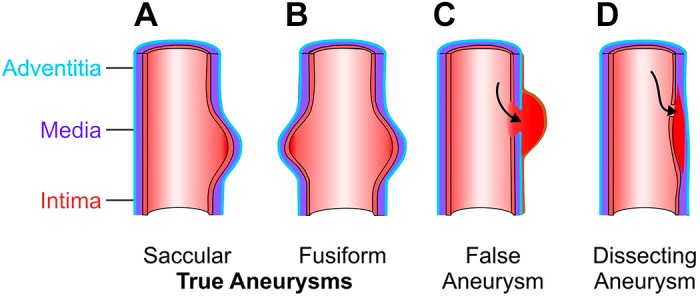

In addition to the location of the aneurysm (TAA vs. AAA), an aneurysm can possess different morphologies. It can be fusiform, when the dilatation occurs in all directions of the circumference of the artery, or saccular, when only a part of the circumference is dilated (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, there can be variations of the type of aortic aneurysm based on the nature of damage to the aortic wall. A false aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm occurs secondary to injury of the aortic wall, leading to leakage of blood into the surrounding periarterial tissue, which acts to delay free rupture. Thus, in a pseudoaneurysm, there is not true dilatation of the aortic wall (Fig. 2C). Aortic dissection occurs when an intimal tear allows blood to enter the medial layer and travel distally within the aortic wall (Fig. 2D). Aortic dissection is further classified based on the location of the dissection, the origin of the intimal tear, and the extent of the dissection. Dissections occurring in the ascending aorta are classified as Stanford Type A (or DeBakey type I/II) and require immediate repair. Stanford Type B (or DeBakey type IIIa/IIIb) dissections occur in the descending aorta and are frequently managed by endovascular surgery or medical treatment (159). Aortic dissection (158), TAA, and the comparative aortic remodeling in TAA and AAA have been reviewed elsewhere (55, 100).

Fig. 2.

Aortic aneurysm can present different morphologies, depending on the type of damage or remodeling in the aortic wall: saccular (A), fusiform (B), false aneurysm (C), and dissecting aneurysm (D).

PATHOLOGY OF AORTIC ANEURYSM

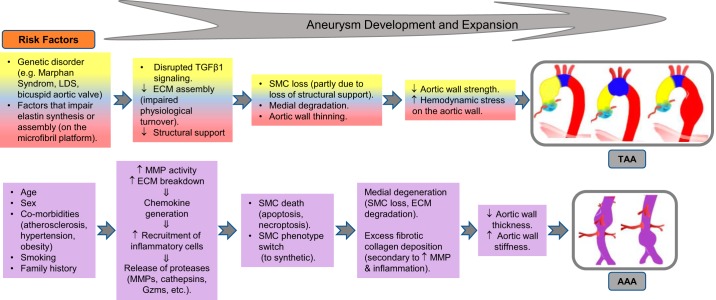

Impaired structural integrity of the aortic ECM, along with impaired cellular function and cell loss, are the key features of an aneurysmal aorta. It is established that TAA and AAA are distinct pathologies that occur in response to different stimuli and can involve different molecular pathways (Fig. 3) (100). Nevertheless, there are a number of commonalities between AAA and TAA involving the cellular and molecular events that will be discussed in this article. Aberrant proteolytic activities within the aortic wall have been implicated in damaging the ECM structure as well as the function of the intimal ECs, medial SMCs, and adventitial fibroblasts. Key pathology processes implicated in aortic aneurysm include inflammation, oxidative stress, SMC apoptosis, and ECM degradation. Inflammation can stimulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) and SMC apoptosis, creating a destructive cycle promoting aortic wall degeneration.

Fig. 3.

A summary of the risk factors and cellular and molecular events that lead to aortic aneurysm. Although there are distinct differences between thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), these 2 pathologies also share common mechanisms. ECM, extracellular matrix; Gzms, granzymes; LDS, Loeys-Dietz syndrome; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; SMC, smooth muscle cells; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor-β1.

INFLAMMATION AND AORTIC ANEURYSM PATHOGENESIS

Inflammation is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of both TAA (51, 191) and AAA (43, 100). An “inflammatory AAA” is a well-defined clinical entity, with defined imaging and surgical characteristics, including a thickened aneurysm wall and extensive peri-aneurysmal fibrosis (172). Both adaptive and innate immune cells have been identified in aortic aneurysm samples (124). Aortic inflammation is characterized by infiltration of neutrophils, mast cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and T and B lymphocytes (28, 197). The infiltrating inflammatory cells have been proposed to secrete chemokines, cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and stimulate the smooth muscle cells to secret MMPs, which degrade aortic structural proteins, resulting in aneurysm formation or expansion (124). The role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of AAA has been well-described in mouse models (46, 191, 253). Macrophages have also been consistently identified in human AAA (23, 27, 54). CD4+ rather than CD8+ T-helper cells (Th cells) have been reported to predominate in human AAA samples (63). In a recent study of human AAA samples, the size of the T cell population within periaortic tissue was positively correlated with larger aneurysm size (180). This was not the case for other inflammatory cells, suggesting the importance of adaptive immunity in AAA pathogenesis.

CD4+ T cells include regulatory (Treg) and effector T cells. Treg cells have been reported to limit AAA development in rodent models (2) by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (236) and TGFβ (243). Effector T cells, whose role is to protect against pathogens, are further subdivided into different classes based on their cytokine secretion profile and include Th1, Th2, Th17, Th22, and Th9 (227). Th1 (63, 180) and Th2 (187), as well as CD8+ T cells (also known as cytotoxic T cells) have been implicated in aortic aneurysm pathogenesis. High circulating levels of Th1, Th9, Th17, and Th22 and low levels of Th2 and Treg cells have been reported in people with aortic dissection (255). Analysis of aneurysmal tissue along with plasma in a Brazilian cohort of 30 patients showed a presence of cells positive for IFNγ, IL-12p35, IL-4, IL-23p19, IL-17R, and IL-22 in the aneurysmal lesion. These authors also reported high expression levels of IFN-γ, TNFα, IL-4, and IL-22 in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells from these AAA patients compared with controls. This led the authors to suggest that Th1, Th2, Th17, and Th22 cells play an important role in the aortic destruction, leading to aneurysmal formation (219). IL-17, a proinflammatory cytokine that is produced by Th17 cells (a subset of inflammatory CD4+ T cells) (220), as well as CD8+ T cells or natural killer T cells (82), has been strongly linked to AAA formation (128, 231). An interaction between T cells and macrophages through a feedback and feedforward mechanism has also been implicated in AAA formation. IFNγ produced by CD4+ T cells can activate macrophages and enhance inflammatory cell recruitment through stimulating cytokine, chemokine, and adhesion molecular expression. Macrophages in turn can produce IL-12 that promotes Th1 activation, potentiating the cycle of ECM destruction and potentially promoting aneurysm formation (43).

Given the proposed role of inflammation in aortic aneurysm pathogenesis (14, 84, 124, 143, 197), this remains a potential target for slowing disease progression (129, 147, 200). There has, however, been no well-designed large trial of an established immune suppression drug in AAA patients yet (70). Currently, the only drugs with anti-inflammatory effects that have been examined in clinical trials have been antibiotics and a mast cell inhibitor. It is possible that immune-suppressive drugs would not be tolerated and have more detrimental than beneficial effects in older patients that usually present with AAA.

DIFFERENT CLASSES OF PROTEASES IMPLICATED IN AORTIC ANEURYSM

A diverse class of proteinases have been implicated in aortic aneurysm pathology, including metalloproteinases, cathepsins, neutrophil elastase, and mast cell chymase and tryptase. A brief list and summary of the roles of these proteases in murine models of AAA is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proposed roles of proteases in AAA in murine models and humans

| Protease | Substrates/Target | Role in Aortic Aneurysm |

|---|---|---|

| MMP-1 | Collagen (I, II, III, VII, VIII, X), aggrecan, gelatine, MMP-2 and MMP-9 | Unclear in animal models; elevated MMP-1 associated with aneurysmal rupture (251). |

| MMP-2 | Collagen IV | MMP-2 deficiency reduced AAA [pressurized elastase model (138) and CaCl2-induced TAA (192)] but caused TAA in response to ANG II (192). |

| MMP-3 | Collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycans | MMP-3 loss reduced AAA in ApoE−/−/ANGII model (198) |

| MMP-8 | Collagens I, II, and III | MMP-8 deficiency did not affect AAA (56) |

| MMP-9 | Collagens (I, IV, V, VII, X, XI, and XIV), elastin, fibronectin, and plasminogen | MMP-9 loss reduced dilatation, inflammation, and AAA (CaCl2 model) (138, 168); elevated MMP9 is associated with increased aneurysm rupture (251). |

| MMP-12 | Fibronectin, elastin, and collagen IV | MMP-12 deficiency reduced dilation and medial disruption in CaCl2 model by decreasing macrophage recruitment; no difference in MMP-2/9 observed in Mmp12−/− mice (137). |

| MMP-13 | Collagens I, II, and III | Inhibition of iNOS reduced AAA by inhibiting MMP-13 production; Mmp-13−/− mice exhibit increased extracellular MMP inducer (CD147) and reduced aortic dilation following elastase infusion (134). |

| MT1-MMP | Collagens, MMP-2 (activation). | Wild-type mice with MT1-MMP-null bone marrow reconstitution showed reduced elastolysis and suppressed AAA (CaCl2 model) (253). |

| ADAMTS-1 | Proteoglycans, aggrecan, versican, thrombospondin-1 and 2, and denatured collagen type I | ADAMTS-1 has been proposed to play a more important role in TAA rather than AAA. Its levels increased in TAA and aortic dissection, with strong correlation with greater versican degradation (174). ADAMTS-1 also increased in AAA specimens, but cleavage of its substrates is not crucial in AAA pathogenesis (234). ADAMTS-1 overexpression in Apoe−/− mice had no impact on AAA (234). |

| ADAMTS-4 | Aggrecan, versican, brevican, and decorin | ADAMTS-4 levels increased in TAA and correlated with greater degradation of versican (174). ADAMTS-4 deficiency reduced AAA (high-fat diet + ANG II) (173). |

| ADAMTS-5 | Aggrecan, versican | Lacking catalytically active ADAMTS-5 worsened TAA (ANG II model). ADAMTS-5 loss caused dilation of ascending aorta during development (53). |

| ADAM-10 | Shedase of membrane-bound ligands, cytokines | ADAM-10 inhibition in ApoE−/− mice protected against AAA induced by high-fat diet and ANG II (102). |

| ADAM-17 | Sheddase-membrane bound receptors, ligands, cytokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes | ADAM17 deficiency in SMCs or ECs or pharmacological inhibition reduced TAA progression, pathological remodeling, and endothelial permeability (191). ADAM17 deficiency in SMCs protected against AAA (BAPN + ANG II model) (109). |

| Cathepsin K | Elastin, collagen | Cathepsin K deficiency reduced AAA, SMC loss, and elastin fragmentation in elastase model (210) but did not affect AAA in ANG II model (10). |

| Cathepsin L | Elastin, collagen | Promotes lesional inflammation, angiogenesis, and protease expression; its deficiency reduced AAA (elastase model) (211) |

| Cathepsin S | Elastin, fibronectin, laminin, and collagen | Cathepsin S deficiency reduced AAA, SMC apoptosis, elastin fragmentation, MMP2/9, and cathepsin K expression and activity, lesional adventitial microvessels, and inflammation (ANG II model) (169). |

| Chymase | MMPs, ANG I, and others | Chymase inhibition reduced AAA in ANG II model (94) and reduced AAA, inflammation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and elastin fragmentation in elastase model (212) |

| Granzyme B | Decorin, fibrillin-1, fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, collagen VII, XVII, and others (4, 25, 26, 85, 179, 228) | GzmB-KO reduced fibrillin-1 loss, medial disruption, and AAA rupture and increased survival in ANG II model (32). GzmB inhibition (by Serpina3n) reduced decorin cleavage and AAA rupture and increased survival and adventitial collagen organization in ANG II model (4). |

| Neutrophil elastase | Elastin | Elevated in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms (39); neutrophil depletion reduced aortic aneurysm in mice (56). |

| Tryptase | Protease maturation, leukocyte recruitment | Secreted by mast cells, proposed to be a biomarker for AAA expansion (258). |

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs), and ADAMs with a thrombospondin domain (ADAMTSs) collectively belong to the metalloproteinase family. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; ANG II, angiotensin II; ECs, endothelial cells; GzmB-KO, granzyme B-knockout; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Metalloproteinase Family

Metalloproteinases are a large family of enzymes that include MMPs, disintegrin metalloproteinases (ADAMs), and ADAMs with a thrombospondin domain (ADAM-TS). MMPs are believed to play a critical role in the degradation of aortic ECM and have also been suggested to have non-ECM functions, which directly contributes to aneurysm formation (15, 122, 140, 171, 221); ADAMTS are also extracellular metalloproteinases that can degrade various ECM proteins, particularly proteoglycans. ADAMs, on the other hand, are membrane-bound metalloproteinases that impose their action primarily through processing of membrane-bound cytokines and growth factors. MMPs have been quite extensively explored in various pathologies, including aortic aneurysm, but the role of ADAMs and ADAM-TSs in vascular pathologies is less explored (60, 75, 191, 193, 262).

MMPs.

The insoluble components of the fibrillar ECM structure, elastin and collagen, support the hemodynamic load of the aortic wall. As such, the action of MMPs in degrading the ECM is thought to be critical in the structural degradation underlying aneurysm formation and progression. MMPs are a family of 23 (mice/humans) zinc-dependent proteases and have been the subject of intense investigations focusing on suppressing aneurysm expansion (12, 13, 122, 126, 171). There is a great degree of overlap in the function of MMPs in degrading ECM proteins, as a number of them can cleave collagen (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP13, and MT1-MMP), and elastin (MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-12), as also summarized in Table 1. MMP-2 and MMP-9 are easily detectable on a gelatin zymography gel, and therefore, they have been the most extensively studied MMPs in murine models as well as human tissue specimens of the aneurysmal aorta (5, 138, 146, 164, 168, 192, 222, 252). In rodent models, MMP2 has been reported to play a uniquely region-specific function in aortic aneurysm such that its loss is protective against AAA (138) but exacerbates TAA due to the resulting impairment of TGFβ activation and synthesis of de novo elastin (192). MMP-3, which degrades both collagen and elastin, is detected in macrophages in aneurysmal tissue and has also been shown to contribute to AAA in murine models (198). MMP-12, also known as macrophage elastase, is elevated in the plasma of patients with aortic dissection (205), and its deficiency in mice improved the outcome of aortic aneurysm by suppressing inflammation and medial disruption (137). In a wide screening of all MMPs in the dilated ascending aorta of patients with tricuspid aortic valves, MT1-MMP (or MMP-14) and MMP-19 were detected to be highly upregulated in the aneurysmal aortas (97). MMPs can be inhibited by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). An overview of the physiology of MMPs and TIMPs in aortic aneurysm and their contribution to ECM and non-ECM events has been reviewed elsewhere (15, 100).

ADAMTSs and ADAMs.

ADAMTS-1, -4 and -5 are the main enzymes responsible for cleavage of large aggregating proteoglycans (60, 111). In TAA and aortic dissection specimens, increased ADAMTS-1 and ADAMTS-4 levels have been significantly correlated with greater degradation of versican, a large extracellular proteoglycan (174). In AAA, however, increased expression of ADAMTS-1 was not accompanied by an increase in the cleavage of its substrates, leading to the suggestion that ADAMTS-1 may play a more important role in TAA but not AAA (234). ADAMTS-1 overexpression in high-fat-fed mice lacking apolipoprotein E (Apoe−/−) receiving angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion did not influence AAA severity (234). In a similar model, ADAMTS-4 deficiency reduced aortic dilation, aneurysm formation, dissection, and aortic rupture (173). Mice expressing truncated ADAMTS-5 (lacking the catalytic domain) show increased aortic dilation in response to ANG II infusion compared with wild-type mice, which was linked to excess accumulation of verscian (60). Upregulation of ADAMTS-1 in mice with catalytically disabled ADAMTS-5 was not sufficient to maintain versican processing and prevent aortic dilation, further suggesting a minor contribution of ADAMTS-1 in aortic aneurysm formation (60). Aggrecan cleavage by ADAMTS-5 has also been reported to be important for normal aortic wall development, especially within the ascending aorta (53). The findings from these studies suggest a complex role for ADAMTSs in aortic aneurysm; although their function in degrading aggrecans and other proteoglycans is necessary to ensure optimal physiological remodeling of the ECM, their loss can lead to either protection or aggravation of aortic aneurysm in rodent models.

Compared with ADAMTSs, the role of ADAMs in aortic aneurysm is less explored. The most studied ADAM, ADAM-17, has been implicated in aortic aneurysm development (191). ADAM-17 can proteolytically process a myriad of substrates (36, 73). SMC- or EC-specific deletion of ADAM-17 protected the aorta from TAA induced by adventitial elastase treatment (191). Similarly, ADAM-17 deficiency in SMCs reduced severity of AAA triggered by a combination of ANG II infusion and lysyl oxidase inhibition (BAPN), provided that protection (109). ADAM-10 was an important regulator for vascular remodeling, and inhibition of ADAM-10 mRNA with miR-103a prevented AAA formation in Apoe−/− mice following a high-fat diet and ANG II infusion (102).

Overall, it is evident that the role of non-MMP metalloproteinases, ADAMs, and ADAMTSs in aortic aneurysm has been underexplored. A better understanding of the function of these metalloproteases in TAA and AAA would provide new insight into the overall proteolytic events that may contribute to the pathological remodeling of the aorta.

Cathepsins

Cathepsins are a family of cysteine proteases that have been suggested to contribute to aneurysm onset and progression. Cathepsins A, D, K, L, and S are elevated in human AAA samples (62, 118, 244). Cathepsin K and S can be produced by SMCs and macrophages under inflammatory conditions and have strong elastinolytic activities (83, 195, 207). Deficiency of cathepsins K, L, and S reduced aneurysm severity in the elastase-induced murine model of AAA (169, 210, 211). The cathepsin inhibitor cystatin C has been consistently reported to be reduced in human AAA specimens (196), and its deficiency exacerbates elastic lamina degradation and AAA severity in murine models (188, 208). In a study involving 476 male AAA patients and 200 age-matched male controls, levels of cathepsin S and cystatin C correlated with aortic diameter positively and negatively, respectively (142). However, the efficacy of cathepsin inhibition in limiting AAA progression remains to be determined.

Neutrophil Elastase

Destruction of the elastin lamellae is a hallmark of aortic aneurysm. Neutrophil elastase is a serine protease that is stored in leukocytes and is released at the cell surface in repose to various stimuli. Monocytes also contain a low level of neutrophil elastase but lose the enzyme when they differentiate into macrophages. Therefore, neutrophils are considered the main source of this elastase. Neutrophil elastase cleaves elastin but can also cleave fibrillar collagens and other ECM proteins such as fibronectin, laminin, and aggrecans. This serine protease has also been reported to activate a number of MMPs (117), thereby also contributing to ECM degradation and other MMP-mediated events. Elastase-mediated degradation of elastin fibers has been suggested to contribute to aortic aneurysm via degradation of the elastic lamellae and disruption of the media as well as through the promotion of elastin fragment-mediated chemotaxis and inflammation. Elevated levels of neutrophil elastase have been reported in patients with AAA (39), whereas neutrophil depletion has been reported to reduce aortic aneurysm in animal models (56). However, a direct link between neutrophil elastase and aneurysm formation remains to be fully established. α1-Antitrypsin (α1AT) is a natural endogenous inhibitor of neutrophil elastase, and its deficiency predisposes to hepatic and/or pulmonary damage, leading to pathologies in these organs (37, 41). Reduced levels of α1AT are reported in AAA patients, although studies on patients lacking α1AT have reported contradicting findings on the relationship between α1AT deficiency and an increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysm (57, 58, 74, 206). Although α1AT replacement therapy is clinically approved for certain α1AT deficiency disorders, there is no evidence that such therapy is effective for aortic aneurysm.

Granzymes

Granzymes (Gzms) are a family of five serine proteases in humans: GzmA (tryptase), GzmB (aspartase), GzmH (chymase), GzmK (tryptase), and GzmM (metase). Although originally believed to be exclusively involved in cytotoxic lymphocyte-induced apoptosis, it is now recognized that granzymes also exert key roles in inflammation, ECM degradation, disruption of epithelial/endothelial barrier function, and pathological angiogenesis (25, 85, 88, 228). Among the granzymes, only the role of GzmB has been assessed in AAA models (4, 32). GzmB is abundant in human AAA tissue and within lymphocytes in the intraluminal thrombus, media, and adventitia (32). GzmB mediates lymphocyte-mediated apoptosis, a process that involves its entry into the target cell through the function of the pore-forming molecule perforin, leading to apoptosis (35, 235). Interestingly, in the original study, deficiency of GzmB, but not perforin, was found to improve survival and reduce aneurysm rupture by preventing fibrillin-1 degradation in a mouse model of AAA (32). However, in subsequent mouse studies, adventitial mast cells were reported to be a major source of GzmB, which was found to contribute to aneurysm rupture through decorin cleavage and loss of adventitial collagen organization and circumferential tensile strength (4). GzmB is inhibited intracellularly by serpinb9 (protease inhibitor-9) to prevent accidental lymphocyte-mediated killing. Whereas no extracellular inhibitors of GzmB have been identified in humans, mice express 13 duplications of human antichymotrypsin (ACT)/serpina3, of which only serpina3n inhibits GzmB. Serpina3n is normally expressed in the murine brain, testes, spleen, lung, and thymus and has been shown to reduce aneurysm rupture in mice. GzmB can be inhibited by Serpins, a family of intracellular serine protease inhibitors (4).

Mast Cell Chymase and Tryptase

Chymase and tryptase are the major endopeptidases that are stored in mast cell secretory granules. Although mast cell chymase and tryptase have broad substrate specificity, they do not directly cleave elastin (162); however, these proteases are capable of activating MMP-2 and MMP-9 (217), which can subsequently cleave elastin and other ECM proteins. Chymase also converts ANG I to ANG II, which has been shown to promote aortic aneurysm in mice. Mast cell chymase and tryptase can also augment inflammation, angiogenesis, and SMC apoptosis (162). The density of mast cells was found to be elevated within the outer media and adventitia of aneurysmal aorta specimens from patients with AAA (226). Mast cell-deficient mice (209) and rats (226) are protected against elastase- or CaCl2-induced AAA, whereas pharmacological inhibition by tranilast, an inhibitor of mast cell degranulation, also attenuates AAA in rats (226). Furthermore, oral administration of the specific chymase inhibitor NK3201 was able to reduce aneurysm in murine, hamster, and dog models (61, 94, 225). These studies collectively suggest an important role for mast cell secretary granules in aortic aneurysm, although this remains to be confirmed by human clinical trials.

TGFβ SIGNALING IN AORTIC ANEURYSM

TGFβ signaling pathway is the primary mechanism for synthesis of fibrillar ECM proteins, elastin, and collagen in the aorta. Alterations in TGFβ signaling pathways have been linked more strongly to TAA but are also relevant in AAA; however, whether it has a protective or detrimental effect remains controversial (45, 144). Multiple steps are involved in TGFβ synthesis, release, and activation of its receptors, which adds to the complexity of TGFβ function. TGFβ ligands (TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3) are transcribed with the latency-associated pro-protein (LAP), which is cleaved intracellularly but stays associated with TGFβ through a noncovalent bond. The TGFβ-LAP complex, referred to as the small latent complex (SLC), is secreted as the large latent complex bound to latent TGFβ-binding protein (LTBP) via a disulfide bond. Upon secretion, LLC is sequestered within the ECM network structure through a covalent bond with fibronectin or fibrillin (265). Activation of the TGFβ pathway is a multistep process that requires proteolytic release of the active TGFβ homodimer (25 kDa) from LLC and SLC, and only then can it bind to TGFβ receptors (215). Proteases identified to date that can mediate release of TGFβ from its latent complex include MMP2, MMP9, MT1-MMP (239, 256), plasmin, and bone morphogenic protein-1 (BMP-1) (65). Therefore, it is important to recognize that in addition to their ECM-degrading function, an increase in activity of MMPs can also lead to an increase in ECM synthesis through their role in activation of latent TGFβ. Upon binding of TGFβ ligand to TGFβ receptor type II (TGFβRII), it dimerizes with and phosphorylates TGFβRI, which propagates through signaling through phosphorylation of the Smad pathway (Smad2/3). However, mutation of either receptor (TGFβRI or TGFβRII) is sufficient to interrupt the activation of this signaling pathway despite an abundant presence of TGFβ ligand.

Marfan Syndrome (MFS) is the most extensively studied genetic disorder associated with TAA. MFS is caused by mutations in the gene that encodes Fibrillin-1 (Fbn1), the scaffold required for assembly of elastin fibers (50). MFS type 2 (MFS2) has been linked to a mutation in TGFβRII, leading to interruption of the TGFβ signaling pathway and impaired ECM production (149). MFS has been well documented to be associated with mutation of fibrillin-1, causing elastin fiber fragmentation, and potentially TGFβ hyperactivity (80, 157). TGFβ hyperactivity in MFS has been suggested to increase angiotensin II signaling that can induce TGFβ transcription and upregulate expression of MMPs involved in activation of latent TGFβ (MMP2, MMP9, and MT1-MMP) (178). However, TGFβ neutralization in an ANG II model was not protective but rather promoted fatal aortic dissections (243). Similarly, treatment of MFS patients with losartan to suppress the TGFβ activity did not protect against aortic dilation, need for surgery, or death (119). The proposed TGFβ hyperactivity in MFS patients could also be because in the absence of fibrillin-1 TGFβ is unable to tether to the ECM in its latent form, and as such it becomes overtly available to activate its receptors and the signaling pathway. Increasing evidence shows that targeting TGFβ does not offer any beneficial effects in MFS. Neutralizing TGFβ with 1D11 anti-TGFβ antibody in Fbn1C1039G/+ MFS or the severe Fbn1mgR/mgR model resulted in more adverse architectural remodeling and worsened aortopathy in mice (40). Moreover, genetic manipulation of TGFβ signaling molecules, by reduction of SMAD4 (Smad4+/−) (90), or TGFβ2 (Tgfb2+/−) (132) or deletion of TGFRII in SMCs (127) in Fbn1C1039G/+ MFS mice aggravated the aortopathy. Therefore, it is possible that TGFβ is not the driving force in the development of TAA in MFS patients and that other factors, such as the mechanical destabilization of elastin fibers in the absence of functional fibrillin-1, may be the main cause of TAA formation. This notion would be consistent with the report that increased TGFβ activity occurs only in advanced stages of disease development and that TGFβ signaling is unaltered in young Fbn1C1039G/+ MFS mice despite the early presence of aortic disease (249), further questioning the causal role of TGFβ in this disease.

Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS) is another connective tissue disorder with phenotypic overlap with MFS, presenting with early and progressive aortic root enlargement, whereas LDS patients also show high risk of aneurysm and dissection in smaller arteries (136). LDS is most often caused by heterozygous mutation of TGFβRI or TGFβRII, preventing their dimerization upon binding of TGFβ ligand, and significantly reducing the TGFβ signaling output (136). In addition, mutations that disrupt production, processing, or activity of the TGFβ pathway such as alterations of TGFβ ligands TGFβ2 (24), TGFβ3 (20), and TGFβ receptors I and II (135) and the signal transducers of the TGFβ pathway, Smad3 (232) and Smad4 (218), have been linked to LDS (131). Mice lacking TGFβRII in SMCs (Tgfbr2flx/flx/Myh11CreERT2) and mice with global reduction of TGFβRII (Tgfbr2G357W/+) have been used as animal models of LDS (64). TAA in these animals, similar to LDS patients, has been attributed to an override of TGFβ signaling; however, it remains to be demonstrated that neutralization of TGFβ improves the disease outcome in LDS patients or animal models (144). Therefore, despite the well-documented increase in activity of the TGFβ signaling pathway in MFS and LDS patients and animal models, its inhibition has not so far offered clear therapeutic benefit, and in some animal models it exacerbates the disease. Given the importance of TGFβ signaling for physiological turnover of the aortic wall (and perhaps other arteries), it is not surprising that its inhibition to below the physiological levels would result in adverse outcomes. TGFβ has also been reported to be protective against AAA, since its neutralization (243) or interruption of its downstream signaling pathway following loss of SMAD3 (216) or SMAD4 (259) enhanced inflammation and susceptibility to AAA. Increased TGFβ activity has been proposed to contribute to protection of diabetic patients and animal models to aortic aneurysm through increased ECM synthesis in the aortic wall (125). Therefore, limiting TGFβ signaling in aortic aneurysm may not be better targeted by aiming to suppress excess activity without disrupting baseline activity of this signaling pathway.

CELL DEATH IN AORTIC ANEURYSM

Multiple cellular and molecular events are proposed to be responsible for the degenerative pathological changes taking place during the development of aortic aneurysm. The suggested contribution of each of the major vascular and inflammatory cell types has been recently reviewed by Quintana and Taylor (170). This section will focus on medial SMCs, which are major contributors to aortic function, and will examine the reported cell death mechanisms of these cells in aortic aneurysm.

Decreased medial SMC density is a shared pathological feature of AAA and TAAs. Apoptotic markers such as fragmented DNA and activated caspase-3 are detected in human and animal aortic aneurysm tissues (86, 91, 101, 139, 202, 245), suggesting an upregulation of apoptotic activity associated with aneurysm. The majority of apoptotic cells in aneurysm-affected aortic wall are SMCs, identified by colocalized TUNEL positivity with SMC markers, including myosin heavy chain or calponin (150, 242). It has been difficult to prove the exact triggers of apoptosis in human aneurysm. However, many factors present in aneurysmal tissues, including enhanced oxidative stress, loss of matrix support, and proapoptotic inflammatory cells, and cytokines are capable of causing cell apoptosis. Experimental approaches targeting inflammation, such as the removal of mast cells (209) or genetic deletion of the chemokine receptor CCR2 (257), were found to attenuate apoptosis, supporting a causal relationship between inflammation and cell death.

Loss of SMCs to apoptosis also impairs the intrinsic repair mechanism because vascular SMCs are the major cell type responsible for the biosynthesis of elastin and other ECM proteins in the blood vessel wall. Indeed, administration of the pan caspase inhibitor, quinoline-Val-Asp-difluorophenoxymethylketone (Q-VD-OPh), protected Apoe−/− mice against ANG II-induced aneurysm (254). The stress mediator protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) has been shown to regulate SMC apoptosis, among its other functions. PKCδ levels are elevated in SMCs of human and mouse AAA tissues (150), and PKCδ deficiency protected mice against experimental aneurysm by preserving SMCs loss and reducing inflammation (150). Conversely, experimental approaches that compromise cell survival accelerate aneurysm development. Shen et al. (194) observed diminished levels of active Akt in the medial layer of aortic wall from patients of sporadic TAAs. Mice deficient in Akt2 respond to ANG II with more profound SMC apoptosis and more severe aortic aneurysm compared with the wild-type controls (194). Apelin (a member of adipokines) is an endogenous peptide produced by a variety of cell types, including ECs and vascular SMCs. In a recent study, Wang et al. (242) showed that apelin protects aortic SMCs from apoptosis. Apelin deficiency potentiated AAA in mice by increasing SMC apoptosis and oxidative stress, whereas supplementation with a long-lasting apelin analog prevented AAA and aortic rupture (242).

Intriguingly, studies in animal models suggest that inhibition of caspases produces little effect on established aneurysms (254). Among other caspase-independent forms of cell death, necroptosis has been implicated in many human diseases, including major cardiovascular disorders (34, 79, 260). Similar to how caspases are key intracellular mediators of apoptosis, receptor interacting protein kinases (RIPKs) are essential signaling mediators of necroptosis. In most cell types, the complex formation between RIPK1, RIPK3, and Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) allows the cell to undergo necroptosis via direct phosphorylation of mixed-lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) by RIPK3 [recently reviewed by Shan et al. (189)]. Elevated levels of RIPK3 have been reported in human and mouse AAAs (240). In addition, mice lacking one or both copies of the Ripk3 gene are resistant to AAA formation in an elastase model (240). The development of RIPK1 inhibitors such as necrostatin-1 will permit in vivo investigation of the function of this kinase in various disease models, since mice lacking the Rip1 gene die shortly after birth (166). In multiple mouse models of AAAs, inhibition of RIPK1 with necrostatin-1 or a dual RIPK1/RIPK3 inhibitor (GSK’074) protected against cell loss and inflammation (241, 264). An optimized version of necrostatin-1, Nec-1s (214), inhibited growth of an already existing aneurysm in an elastase model of AAA (241), suggesting that targeting RIPKs may be a candidate strategy to treat small aortic aneurysms.

Cell Death and Vascular Inflammation

Cell death and inflammation are frequently closely related. Cell death, through various mechanisms, may trigger inflammatory responses by releasing damage-associated molecular pattern molecules such as high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) and cyclophilin A. Mice deficient in Ppia, the gene encoding cyclophilin A, are resistant to aortic aneurysm induction by ANG II (186). Using the Tgfbr1 deficiency-mediated aortic aneurysm and dissection model, Zhou et al. (263) reported that the loss of TGFβ signaling increased cyclophilin A production by SMCs and that treatment with a cyclophilin A inhibitor ameliorated aneurysm dilation. Levels of HMGB1 are reportedly elevated in human and mouse AAA tissues (114, 190). Antibody-mediated inhibition of HMGB1 attenuated aneurysm formation in mice (114, 190). It is important to recognize that necrotic SMCs may not be the sole source of HMGB1 in aneurysmal tissues. Macrophages and other inflammatory cells are also capable of releasing HMGB1.

The inflammatory perspective of necroptosis is complex and disease dependent (110). Experimental evidence suggests that RIPK3 may have a role in inflammation independent of its function in cell death (151). In SMCs, RIPK3 has been demonstrated to be necessary for NF-κB (p65) phosphorylation and expression of inflammatory cytokines Ccl2 (MCP-1), Il6, Tnf, and Vcam1 in nonnecrotic conditions (240).

In general, apoptosis alone does not trigger an inflammatory response owing to the intact plasma membrane of apoptotic cells. However, when an apoptotic cell is not removed promptly, either by neighboring cells or phagocytes such as macrophages, it will undergo postapoptotic or secondary necrosis. Defective clearance of apoptotic cells, termed efferocytosis, is increasingly recognized as a major driver of necrotic core formation of advanced atherosclerotic lesions (3). Several signaling mechanisms are involved in the various steps of efferocytosis. Kojima et al. (115) observed elevated levels of CD47, a “don’t eat me” signal, in SMCs of human AAA tissues and were able to inhibit aneurysm formation with an anti-CD47 antibody in mice, suggesting another candidate strategy to treat small aortic aneurysm.

Phenotypic Switching of SMCs

The concept of SMC phenotypic switch is well established in the context of atherosclerosis and restenosis, as recently reviewed (19). In a healthy arterial wall, SMCs are considered to be contractile because they maintain vascular tone and remain rather quiescent. However, in pathological conditions such as aortic aneurysm, they are believed to dedifferentiate into a synthetic phenotype whereby they secrete abundant amounts of ECM proteins and proliferate and migrate in an attempt to repair injury. This process is referred to as phenotypic switching and is thought to occur at a very early stage of vascular pathology. Oxidative stress has been proposed to be one of triggering factor in initiating the switch from contractile to synthetic phenotype of SMC in aortic aneurysm (163). The importance of SMC phenotypic switching in aneurysm pathophysiology was suggested in studied using mice deficient of KLF4, a transcription factor known to control SMC phenotype, which was sufficient to confer aneurysm protection in both elastase and ANG II models (182). Although it remains to be proven whether KLF4 contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis primarily through regulating SMC phenotype, this study showed that KLF4 binds to the promoters of smooth muscle contractile genes during aneurysm formation, which provides support for the role of phenotypic switch in aneurysm pathogenesis (182).

As more studies from mice with SMC-targeted gene deletion are emerging, it is generally believed that in response to aneurysmal stimuli, surviving SMCs (often undergone a switch to a synthetic phenotype) actively contribute to the pro-inflammatory and degenerative state of the vessel wall. Thus far, SMCs in human and mouse aneurysmal tissues have been found to have diminished expression of contractile proteins, including SM-specific α-actin (α-SMA), SM22α, and SM-specific myosin heavy chain (1, 133, 182, 261). Mutations in α-SMA have been suggested to cause TAA and TAA dissection (76) as a result of impaired SMC contractility and ability to maintain ECM (113). Moreover, associated with loss of contractile proteins, SMCs in aneurysmal tissues express elevated levels of several MMPs (81, 194). As experimental technologies such as lineage tracing and single-cell RNA sequencing become more widely available, a more complete molecular signature of SMC populations is expected to emerge soon.

OTHER ARTERIAL CELLS IN AORTIC ANEURYSM

Resident vascular cells other than SMCs are also thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of aortic aneurysm. Adventitial fibroblasts are increasingly appreciated for their role in vascular remodeling (38). In mice, ANG II infusion causes adventitial fibroblasts to expand in numbers, presumably through proliferation (223), whereas immunostaining also suggests the occurrence of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation during aneurysm development (105). In addition to regulating perivascular fibrosis, adventitial fibroblasts may actively participate in the recruitment and differentiation of monocytes by releasing MCP1 (223). However, the precise role of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in aortic aneurysm is yet to be fully explored. Even less is known about how ECs may contribute to aneurysm pathophysiology. Emerging evidence implicates endothelial dysfunction in oxidative stress via an endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-mediated mechanism (203). Many questions remain to be addressed, particularly in the understanding of cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions. Such knowledge may reveal new therapeutic targets.

CURRENT STATE OF PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPIES FOR AORTIC ANEURYSM: DATA FROM RANDOMIZED CLINICAL DRUG TRIALS

In clinical practice, large (≥55 mm in men and ≥50 mm in women) asymptomatic or symptomatic AAAs are treated by open or endovascular repair (31, 248). Because of the availability of ultrasound screening programs in the high-income countries, aortic aneurysms can usually be identified when they are small and asymptomatic (31, 67, 99, 248). Patients with small AAAs are simply monitored by repeat clinical assessment and imaging surveillance. Because no current drug therapies are available to effectively limit AAA growth, surgical repair is the only treatment available to prevent aortic rupture (31, 67, 248). Because surgical repair is not without complications, there has been substantial interest in testing potential drug therapies for small AAAs in clinical trials. The best design to use for such trials is controversial (16, 67, 72). A number of different end points have been used in prior trials, including imaging, clinical events, and surrogate biological markers.

Imaging and Clinical Events as the End Point in Clinical Trials

Assessing AAA growth is the most common outcome used in clinical trials. Aneurysm growth is monitored by repeat ultrasound imaging (21, 89, 108, 130, 147, 154, 165, 200, 230), repeat magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (247), or computed tomography (CT) (16). Clinical events, specifically requirements for surgical repair or aortic rupture, are another end point that is used in assessing the outcome of a trial. Although many previous trials have collected this outcome measure (21, 89, 108, 130, 147, 154, 200, 230), none so far have been sufficiently powered or are long enough to adequately assess this end point (67). In addition, there is a lack of consensus on the most appropriate imaging assessment of aortic aneurysm progression, with different methods of assessing aneurysm size on ultrasound (e.g., outside adventitia to outside adventitia versus inner wall to inner wall) and MRI/CT (e.g., infrarenal aortic volume versus orthogonal aortic diameter versus axial aortic diameter) being used or proposed (21, 89, 108, 130, 147, 154, 200, 230, 247). Furthermore, all imaging assessments of aneurysm size are subject to measurement error that is within the range of annual change in aneurysm size (17). A cohort study has suggested that assessment of aortic volume, as opposed to the currently used aortic diameter, may be a more sensitive measure of AAA growth (246), but it remains unclear how this end point is valued by patients and clinicians. The clinically meaningful change in AAA growth that a drug needs to achieve to be considered effective is also not clearly defined. It has been proposed, based on simulations, that a 40% reduction in AAA diameter increase is required to achieve a clinically meaningful 13% absolute reduction in AAA repair over 20 yr (16). However, there has been no widespread agreement on this definition. The simulations that this is based on also involve numerous assumptions that are not necessarily borne out in clinical practice, such as that AAA repair occurs exactly at 55 mm and that AAA size and growth can be accurately modeled over extended periods (17, 246).

Surrogate Biological Markers Serving as End Points for Clinical Trials

Surrogate biological markers of AAA progression or pathogenesis have been used as primary end points in several drugs trials. These surrogate markers have included circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as arachidonic acid, IL-6, and osteopontin and the densities of inflammatory cells such as macrophage and T cells and concentrations of proteolytic enzymes such as MMPs within aneurysmal biopsies (48, 59, 129, 148, 165, 175). Biological surrogate markers are attractive as the primary end point for drugs due to the low estimated samples sizes and short follow-up needed for such trials, suggesting a cost-efficient design (48, 59, 129, 148, 165, 175).

However, it is unclear whether changes in biological markers translate into clinical benefits. Prior research on doxycycline, a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor, is a good example of this dilemma. Numerous animal studies have suggested the importance of inflammation and ECM degradation in AAA pathogenesis. Doxycycline has been reported to limit AAA development in animal models by inhibiting inflammation and ECM remodeling (67). A randomized trial in AAA patients awaiting surgical repair reported that doxycycline administration inhibited aortic density of neutrophils and cytotoxic T cells and reduced aortic concentrations of interleukin-6, -8, and -13 (129). However, a 286-person placebo-controlled randomized trial in patients with small AAAs reported significantly faster growth in patients allocated doxycycline (147). A further doxycycline trial is expected to be reported in the near future, but currently, the findings do not support the value of using biological markers as a surrogate end point for drug screening or suggest that doxycycline is a beneficial therapy for AAA (16). The lack of a robust beneficial effect of doxycycline in patients with small AAAs could be due to a number of reasons. First, it is well established that MMPs are an absolute requirement for other types of wound healing, owing to their non-ECM related functions such as their critical roles in the transition through various stages of inflammation, granulation, tissue formation, and remodeling (18, 30, 42, 52, 116, 145, 153, 179). As such, it is likely that MMPs are necessary for vascular “wound healing” in the aneurysmal aorta. Second, from the use of broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors in cancer clinical trials, of which all were discontinued, it became clear that the activity of many of the 24 MMPs should be promoted, not inhibited. It has been proposed that at least 10 of the 24 murine MMPs elicit anti-tumorigenic and/or anti-inflammatory roles (reviewed in Ref. 52). Therefore, if the primary target of doxycycline was indeed MMPs in the AAA trials, it is not surprising that broad-spectrum MMP inhibition would augment inflammation and/or impede vascular repair and remodeling, thereby exacerbating AAA pathogenesis. Therefore, given the diverse functions of various MMPs, global inhibition of MMPs may not be an effective treatment strategy for aortic aneurysm.

For various reasons, such as design controversies and poor drug choice, the overall findings from prior trials have failed to provide compelling evidence that any medications effectively limit AAA growth or aneurysm-related clinical events (i.e., rupture or need for surgical repair) in patients with small AAAs (21, 89, 108, 130, 147, 154, 200, 230). A few small trials focused on AAA growth (154, 230) or biomarker (48, 59, 129) have had positive results, but the findings from these studies have not been confirmed in larger trials (147). A number of additional trials are ongoing, such as those testing the angiotensin receptor blocker, telmisartan (152), and the diabetes drug metformin [National Library of Medicine; ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03507413 (2018)]. These trials are based on prior evidence for ANG II in AAA pathogenesis and both preclinical (67) and clinical observational data suggesting that metformin is associated with a reduction in AAA growth and clinical events (68, 69). Given the design issues mentioned above, it is possible that these trials will also be too small with too short follow-up to provide any compelling evidence for a drug therapy. An international collaborative effort to reach consensus on the optimal approach to small aortic aneurysm trials would be beneficial to resolve this current road block in drug development.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Aortic aneurysm is a potentially fatal disease that has no clear pharmacological treatment. This is partly due to our limited understanding of the diverse factors that contribute to disruptive remodeling of the aortic wall. In particular, it remains unclear how targeting one of the enormous number of molecules implicated in aortic aneurysm in rodents affects other pathways or, most importantly, translates to patients. It is critical to ensure that in interpreting the preclinicial findings, attention is given to the type of experimental models used and its relevance to aortic aneurysm in patients. With this in mind, new animal models and more innovative ways of studying aortic aneurysm in patients are needed.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-088447 and R01-HL-122562 (to B. Liu); the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Townsville Hospital and Health Services Study, the Education and Research Trust Fund, Queensland Government, the National Heart Foundation and James Cook University, Practitioner Fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council, and a Senior Clinical Research Fellowship from the Queensland Government, Australia. (to J. Golledge); the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (to D. J. Granville); and the Canadian Institute for Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, Canada Foundation for Innovation (to Z. Kassiri).

DISCLOSURES

J. Golledge has received funds to consult Amgen and Reven and travel expenses to speak at international and national meetings. D. J. Granville is a cofounder and serves as a consultant/chief scientific officer for viDA Therapeutics. B. Liu. and Z. Kassiri have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.K. conceived and designed research; Z.K. prepared figures; B.L., D.J.G., J.G., and Z.K. drafted manuscript; B.L., D.J.G., J.G., and Z.K. edited and revised manuscript; B.L., D.J.G., J.G., and Z.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ailawadi G, Moehle CW, Pei H, Walton SP, Yang Z, Kron IL, Lau CL, Owens GK. Smooth muscle phenotypic modulation is an early event in aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 138: 1392–1399, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ait-Oufella H, Wang Y, Herbin O, Bourcier S, Potteaux S, Joffre J, Loyer X, Ponnuswamy P, Esposito B, Dalloz M, Laurans L, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Natural regulatory T cells limit angiotensin II-induced aneurysm formation and rupture in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 2374–2379, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allin KH, Tremaroli V, Caesar R, Jensen BA, Damgaard MT, Bahl MI, Licht TR, Hansen TH, Nielsen T, Dantoft TM, Linneberg A, Jørgensen T, Vestergaard H, Kristiansen K, Franks PW, Hansen T, Bäckhed F, Pedersen O; IMI-DIRECT consortium . Aberrant intestinal microbiota in individuals with prediabetes. Diabetologia 61: 810–820, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4550-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ang LS, Boivin WA, Williams SJ, Zhao H, Abraham T, Carmine-Simmen K, McManus BM, Bleackley RC, Granville DJ. Serpina3n attenuates granzyme B-mediated decorin cleavage and rupture in a murine model of aortic aneurysm. Cell Death Dis 2: e209, 2011. [Erratum in: Cell Death Dis 2: e215, 2011.] doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annabi B, Shédid D, Ghosn P, Kenigsberg RL, Desrosiers RR, Bojanowski MW, Beaulieu E, Nassif E, Moumdjian R, Béliveau R. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activities in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 35: 539–546, 2002. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.121124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnaoutakis DJ, Propper BW, Black JH 3rd, Schneider EB, Lum YW, Freischlag JA, Perler BA, Abularrage CJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of unruptured thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms in the United States. J Surg Res 184: 651–657, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnaoutakis GJ, Schneider EB, Arnaoutakis DJ, Black JH 3rd, Lum YW, Perler BA, Freischlag JA, Abularrage CJ. Influence of gender on outcomes after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 59: 45–51, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aune D, Schlesinger S, Norat T, Riboli E. Tobacco smoking and the risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sci Rep 8: 14786, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avdic T, Franzén S, Zarrouk M, Acosta S, Nilsson P, Gottsäter A, Svensson AM, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Eliasson B. Reduced long-term risk of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a nationwide observational study. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e007618, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai L, Beckers L, Wijnands E, Lutgens SP, Herías MV, Saftig P, Daemen MJ, Cleutjens K, Lutgens E, Biessen EA, Heeneman S. Cathepsin K gene disruption does not affect murine aneurysm formation. Atherosclerosis 209: 96–103, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbier M, Gross MS, Aubart M, Hanna N, Kessler K, Guo DC, Tosolini L, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Regalado E, Varret M, Abifadel M, Milleron O, Odent S, Dupuis-Girod S, Faivre L, Edouard T, Dulac Y, Busa T, Gouya L, Milewicz DM, Jondeau G, Boileau C. MFAP5 loss-of-function mutations underscore the involvement of matrix alteration in the pathogenesis of familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Am J Hum Genet 95: 736–743, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbour JR, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS. Proteinase systems and thoracic aortic aneurysm progression. J Surg Res 139: 292–307, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbour JR, Stroud RE, Lowry AS, Clark LL, Leone AM, Jones JA, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS. Temporal disparity in the induction of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases after thoracic aortic aneurysm formation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132: 788–795, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu R, Fan D, Kandalam V, Lee J, Das SK, Wang X, Baldwin TA, Oudit GY, Kassiri Z. Loss of Timp3 gene leads to abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in response to angiotensin II. J Biol Chem 287: 44083–44096, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basu R, Kassiri Z. Extracellular matrix remodeling and abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Clin Exp Cardiol 4: 1–8, 2013. doi: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter BT, Matsumura J, Curci J, McBride R, Blackwelder WC, Liu X, Larson L, Terrin ML; N-TA(3)CT Investigators . Non-invasive Treatment of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Clinical Trial (N-TA(3)CT): Design of a Phase IIb, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of doxycycline for the reduction of growth of small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Contemp Clin Trials 48: 91–98, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AW, Sedrakyan A, Mao J, Venermo M, Faizer R, Debus S, Behrendt CA, Scali S, Altreuther M, Schermerhorn M, Beiles B, Szeberin Z, Eldrup N, Danielsson G, Thomson I, Wigger P, Björck M, Cronenwett JL, Mani K; International Consortium of Vascular Registries . Variations in abdominal aortic aneurysm care: a report from the International Consortium of Vascular Registries. Circulation 134: 1948–1958, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellac CL, Dufour A, Krisinger MJ, Loonchanta A, Starr AE, Auf dem Keller U, Lange PF, Goebeler V, Kappelhoff R, Butler GS, Burtnick LD, Conway EM, Roberts CR, Overall CM. Macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-12 dampens inflammation and neutrophil influx in arthritis. Cell Reports 9: 618–632, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett MR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 118: 692–702, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertoli-Avella AM, Gillis E, Morisaki H, Verhagen JMA, de Graaf BM, van de Beek G, Gallo E, Kruithof BP, Venselaar H, Myers LA, Laga S, Doyle AJ, Oswald G, van Cappellen GW, Yamanaka I, van der Helm RM, Beverloo B, de Klein A, Pardo L, Lammens M, Evers C, Devriendt K, Dumoulein M, Timmermans J, Bruggenwirth HT, Verheijen F, Rodrigus I, Baynam G, Kempers M, Saenen J, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Minatoya K, Matsukawa R, Tsukube T, Kubo N, Hofstra R, Goumans MJ, Bekkers JA, Roos-Hesselink JW, van de Laar IM, Dietz HC, Van Laer L, Morisaki T, Wessels MW, Loeys BL. Mutations in a TGF-β ligand, TGFB3, cause syndromic aortic aneurysms and dissections. J Am Coll Cardiol 65: 1324–1336, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bicknell CD, Kiru G, Falaschetti E, Powell JT, Poulter NR; AARDVARK Collaborators . An evaluation of the effect of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on the growth rate of small abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized placebo-controlled trial (AARDVARK). Eur Heart J 37: 3213–3221, 2016. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanchard JF, Armenian HK, Friesen PP. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm: results of a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 151: 575–583, 2000. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blomkalns AL, Gavrila D, Thomas M, Neltner BS, Blanco VM, Benjamin SB, McCormick ML, Stoll LL, Denning GM, Collins SP, Qin Z, Daugherty A, Cassis LA, Thompson RW, Weiss RM, Lindower PD, Pinney SM, Chatterjee T, Weintraub NL. CD14 directs adventitial macrophage precursor recruitment: role in early abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000065, 2013. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boileau C, Guo DC, Hanna N, Regalado ES, Detaint D, Gong L, Varret M, Prakash SK, Li AH, d’Indy H, Braverman AC, Grandchamp B, Kwartler CS, Gouya L, Santos-Cortez RL, Abifadel M, Leal SM, Muti C, Shendure J, Gross MS, Rieder MJ, Vahanian A, Nickerson DA, Michel JB, Jondeau G, Milewicz DM; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Go Exome Sequencing Project . TGFB2 mutations cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections associated with mild systemic features of Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet 44: 916–921, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ng.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boivin WA, Cooper DM, Hiebert PR, Granville DJ. Intracellular versus extracellular granzyme B in immunity and disease: challenging the dogma. Lab Invest 89: 1195–1220, 2009. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boivin WA, Shackleford M, Vanden Hoek A, Zhao H, Hackett TL, Knight DA, Granville DJ. Granzyme B cleaves decorin, biglycan and soluble betaglycan, releasing active transforming growth factor-β1. PLoS One 7: e33163, 2012. [Correction in: PLoS One 7: 2012.] doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boytard L, Spear R, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Acosta-Martin AE, Vanhoutte J, Lamblin N, Staels B, Amouyel P, Haulon S, Pinet F. Role of proinflammatory CD68(+) mannose receptor(−) macrophages in peroxiredoxin-1 expression and in abdominal aortic aneurysms in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 431–438, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brophy CM, Reilly JM, Smith GJ, Tilson MD. The role of inflammation in nonspecific abdominal aortic aneurysm disease. Ann Vasc Surg 5: 229–233, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF02329378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownstein AJ, Kostiuk V, Ziganshin BA, Zafar MA, Kuivaniemi H, Body SC, Bale AE, Elefteriades JA. Genes Associated with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection: 2018 Update and Clinical Implications. Aorta (Stamford) 6: 13–20, 2018. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1639612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler GS, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of signaling molecules to regulate inflammation. Periodontol 2000 63: 123–148, 2013. doi: 10.1111/prd.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, Mastracci TM, Mell M, Murad MH, Nguyen LL, Oderich GS, Patel MS, Schermerhorn ML, Starnes BW. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 67: 2–77.e2, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamberlain CM, Ang LS, Boivin WA, Cooper DM, Williams SJ, Zhao H, Hendel A, Folkesson M, Swedenborg J, Allard MF, McManus BM, Granville DJ. Perforin-independent extracellular granzyme B activity contributes to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Pathol 176: 1038–1049, 2010. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung K, Boodhwani M, Chan KL, Beauchesne L, Dick A, Coutinho T. Thoracic aortic aneurysm growth: role of sex and aneurysm etiology. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e003792, 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi ME, Price DR, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Necroptosis: a crucial pathogenic mediator of human disease. JCI Insight 4: e128834, 2019. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chowdhury D, Lieberman J. Death by a thousand cuts: granzyme pathways of programmed cell death. Annu Rev Immunol 26: 389–420, 2008. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chute M, Jana S, Kassiri Z. Disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs and ADAM-TSs), the emerging family of proteases in heart physiology and pathology. Current Opin Physiol 1: 34–45, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2017.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark VC, Marek G, Liu C, Collinsworth A, Shuster J, Kurtz T, Nolte J, Brantly M. Clinical and histologic features of adults with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in a non-cirrhotic cohort. J Hepatol 69: 1357–1364, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coen M, Gabbiani G, Bochaton-Piallat ML. Myofibroblast-mediated adventitial remodeling: an underestimated player in arterial pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2391–2396, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.231548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen JR, Keegan L, Sarfati I, Danna D, Ilardi C, Wise L. Neutrophil chemotaxis and neutrophil elastase in the aortic wall in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Invest Surg 4: 423–430, 1991. doi: 10.3109/08941939109141172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook JR, Clayton NP, Carta L, Galatioto J, Chiu E, Smaldone S, Nelson CA, Cheng SH, Wentworth BM, Ramirez F. Dimorphic effects of transforming growth factor-β signaling during aortic aneurysm progression in mice suggest a combinatorial therapy for Marfan syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 911–917, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cottin V, Cordier JF. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: an experimental and clinically relevant phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 1605, 2005. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.172.12.1605a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox JH, Starr AE, Kappelhoff R, Yan R, Roberts CR, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase 8 deficiency in mice exacerbates inflammatory arthritis through delayed neutrophil apoptosis and reduced caspase 11 expression. Arthritis Rheum 62: 3645–3655, 2010. doi: 10.1002/art.27757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dale MA, Ruhlman MK, Baxter BT. Inflammatory cell phenotypes in AAAs: their role and potential as targets for therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 1746–1755, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dasouki M, Markova D, Garola R, Sasaki T, Charbonneau NL, Sakai LY, Chu ML. Compound heterozygous mutations in fibulin-4 causing neonatal lethal pulmonary artery occlusion, aortic aneurysm, arachnodactyly, and mild cutis laxa. Am J Med Genet A 143A: 2635–2641, 2007. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daugherty A, Chen Z, Sawada H, Rateri DL, Sheppard MB. Transforming growth factor-β in thoracic aortic aneurysms: good, bad, or irrelevant? J Am Heart Assoc 6: e005221, 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Charo IF, Owens AP 3rd, Howatt DA, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II infusion promotes ascending aortic aneurysms: attenuation by CCR2 deficiency in apoE−/− mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 118: 681–689, 2010. doi: 10.1042/CS20090372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davies RR, Goldstein LJ, Coady MA, Tittle SL, Rizzo JA, Kopf GS, Elefteriades JA. Yearly rupture or dissection rates for thoracic aortic aneurysms: simple prediction based on size. Ann Thorac Surg 73: 17–28, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dawson JA, Choke E, Loftus IM, Cockerill GW, Thompson MM. A randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial to evaluate lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy on proteolysis and inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 41: 28–35, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deery SE, O’Donnell TF, Shean KE, Darling JD, Soden PA, Hughes K, Wang GJ, Schermerhorn ML; Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative . Racial disparities in outcomes after intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 67: 1059–1067, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.07.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietz HC, Cutting GR, Pyeritz RE, Maslen CL, Sakai LY, Corson GM, Puffenberger EG, Hamosh A, Nanthakumar EJ, Curristin SM, Stetten G, Meyers DA, Francomano CA. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature 352: 337–339, 1991. doi: 10.1038/352337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dinesh NE, Reinhardt DP. Inflammation in thoracic aortic aneurysms. Herz 44: 138–146, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00059-019-4786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dufour A, Overall CM. Missing the target: matrix metalloproteinase antitargets in inflammation and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci 34: 233–242, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dupuis LE, Nelson EL, Hozik B, Porto SC, Rogers-DeCotes A, Fosang A, Kern CB. Adamts5(−/−) mice exhibit altered aggrecan proteolytic profiles that correlate with ascending aortic anomalies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 39: 2067–2081, 2019. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dutertre CA, Clement M, Morvan M, Schäkel K, Castier Y, Alsac JM, Michel JB, Nicoletti A. Deciphering the stromal and hematopoietic cell network of the adventitia from non-aneurysmal and aneurysmal human aorta. PLoS One 9: e89983, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elefteriades JA, Sang A, Kuzmik G, Hornick M. Guilt by association: paradigm for detecting a silent killer (thoracic aortic aneurysm). Open Heart 2: e000169, 2015. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eliason JL, Hannawa KK, Ailawadi G, Sinha I, Ford JW, Deogracias MP, Roelofs KJ, Woodrum DT, Ennis TL, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Thompson RW, Upchurch GR Jr. Neutrophil depletion inhibits experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation 112: 232–240, 2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elzouki AN, Eriksson S. Abdominal aortic aneurysms and alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. J Intern Med 236: 587–591, 1994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elzouki AN, Rydén Ahlgren A, Länne T, Sonesson B, Eriksson S. Is there a relationship between abdominal aortic aneurysms and alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZ)? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 17: 149–154, 1999. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1998.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans J, Powell JT, Schwalbe E, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Simvastatin attenuates the activity of matrix metalloprotease-9 in aneurysmal aortic tissue. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 34: 302–303, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fava M, Barallobre-Barreiro J, Mayr U, Lu R, Didangelos A, Baig F, Lynch M, Catibog N, Joshi A, Barwari T, Yin X, Jahangiri M, Mayr M. Role of ADAMTS-5 in aortic dilatation and extracellular matrix remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 38: 1537–1548, 2018. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]