Abstract

Work in adult humans and animals suggest sodium (Na) is stored in tissue reservoirs without commensurate water retention. These stores may protect from water loss, regulate immune function, and participate in blood pressure regulation. A role for such stores early in life, during which total body Na sufficiency is vital for optimal growth, has not been explored. Using data from previously published literature, we calculated total body stores of Na, potassium (K), and chloride (Cl) during fetal development (24–40 wk gestation) using two methods 1) based on the distribution of body water mass within extracellular and intracellular compartments, and 2) reported total mineral content. Based on differences between the models, we argue that Na, and to a lesser extent Cl, but not K, are stored in osmotically inactive pools within the fetus that increase with advancing gestational age. Because human breastmilk is relatively Na deficient, we speculate the fetal osmotically inactive Na pool is vital for providing a sufficient total body Na content that supports optimal postnatal growth.

Keywords: fetus, growth, sodium

INTRODUCTION

Classic teaching of sodium (Na) homeostasis is based on the two-compartment model of body water distribution, with the vast majority of total body Na restricted to the extracellular space and limited Na within the intracellular compartment. However, recent data from adult human and animal studies suggest the presence of a large, osmotically inactive Na storage pool (11). These pools result from negatively charged glycosaminoglycan (GAG) within the skin interstitium binding Na. This binding of sodium does not change the concentration of solutes within the skin interstitium, and therefore, Na is stored without concurrent water retention (8, 11). The density of GAG may allow localized Na concentrations in the interstitial matrix to increase up to 450 meq/L, far exceeding that of serum Na concentrations. Storage and release of Na from osmotically inactive pools may modulate hemodynamics and participate in salt-sensitive versus insensitive hypertension, impact vascular function, extracellular fluid volumes, osmoregulation, and immune function.

Na accumulation and the maintenance of positive Na balance is essential for optimal postnatal growth (1, 10). Abundant animal studies as well as studies in human infants demonstrate that Na deficiency results in impaired growth, though the mechanism(s) of such remain poorly defined. Term, breastfed infants are in a precarious Na balance. Beyond the first postpartum week, breastmilk Na content from mothers delivering at term averages no more than 10 meq/L (5). Assuming the breastfed infant takes in 150 mL/kg per day of breastmilk, the resultant daily Na intake is 1.5 meq/kg per day. Na losses during infancy are primarily urinary. Assuming 75 mL/kg day of urine production and a urine Na concentration of 15 meq/L, urine Na losses average 1.125 meq/kg day. Thus, net Na balance, without accounting for stool or skin losses, is 0.375 meq/kg day. If one further assumes that infant growth averages 25 g/day, with total body water at this stage of development being 70% of body weight, and with an equal distribution of the intracellular and extracellular water compartments (2), the infant requires ~1.26 meq Na/day. This value is calculated as follows: 1) 25 g/day growth, of which 70% = 17.5 g (ml) is water; 2) approximately half of this water is extracellular (9 ml); 3) Na concentration of extracellular water is 140 meq/L; and 4) 9 mL (extracellular fluid) × (140 meq/1,000 mL) = 1.26 meq.

Thus, a decrease in Na intake, resulting from decreasing Na content of breastmilk with advancing time postpartum or decreased intake of breastmilk, increased urine Na losses or increased stool/skin Na losses put the infant at risk for total body Na deficiency with resultant growth impairment.

From these above calculations, along with evidence of osmotically inactive Na stores in human adults, we sought to determine whether osmotically inactive Na pools may exist in human infants. Such pools may prove protective during depletion of osmotically active Na early during postnatal life and be mobilized for growth (8). We utilized literature providing human fetal body composition (12) and water compartment distribution (2) data to calculate changes in total body stores of Na, potassium (K), and chloride (Cl) during fetal development (24–40 wk gestation). Total body mineral content was estimated by two methods, with calculations based on 1) body water compartments (BW method, Table 1), and 2) reported mineral content per 100 g fat free mass (MC method). Calculations of Na content based on BW compartments are detailed in Table 1, and similar approaches were used for K and Cl. Total body Na calculations included an estimated amount of sodium in bone. This determination was based on the total fetal calcium content, the assumption that all calcium was present in bone, and that the molar ratio of calcium to sodium in bone is 30:1 (3). Differences between these calculations were interpreted to represent osmotically inactive stores. The content of Na, K, and Cl within water compartments were estimated to be 140, 4, and 110 meq/L (extracellular) and 4, 150, and 10 meq/L (intracellular), respectively.

Table 1.

Body water compartments and Na content of reference fetuses

| Gestational Age, weeks | Body Mass, g | Total Body Fluid Mass, g | Extracellular, % Fluid Mass | Intracellular, % Fluid Mass | Extracellular Fluid Mass, g | Intracellular Fluid Mass, g | Extracellular Na, meq | Intracellular Na, meq | Bone Na, meq | Total Na, meq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 690 | 611 | 60 | 25 | 367 | 153 | 51.4 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 55.5 |

| 25 | 770 | 681 | 59 | 25 | 402 | 170 | 56.2 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 60.8 |

| 26 | 880 | 775 | 58 | 26 | 450 | 202 | 63.0 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 68.5 |

| 27 | 1,010 | 887 | 56 | 26 | 497 | 231 | 69.5 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 75.4 |

| 28 | 1,160 | 1,015 | 55 | 27 | 558 | 274 | 78.2 | 1.1 | 5.7 | 85.0 |

| 29 | 1,318 | 1,149 | 54 | 28 | 621 | 322 | 86.9 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 94.6 |

| 30 | 1,480 | 1,285 | 53 | 28 | 681 | 360 | 95.3 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 104.0 |

| 31 | 1,650 | 1,427 | 52 | 29 | 742 | 414 | 103.9 | 1.7 | 8.2 | 113.7 |

| 32 | 1,830 | 1,576 | 50 | 29 | 788 | 457 | 110.3 | 1.8 | 9.1 | 121.3 |

| 33 | 2,020 | 1,733 | 49 | 30 | 849 | 520 | 118.9 | 2.1 | 10.3 | 131.3 |

| 34 | 2,230 | 1,904 | 48 | 31 | 914 | 590 | 128.0 | 2.4 | 11.6 | 141.9 |

| 35 | 2,450 | 2,082 | 47 | 31 | 979 | 646 | 137.0 | 2.6 | 13.1 | 152.7 |

| 36 | 2,690 | 2,276 | 46 | 32 | 1,047 | 728 | 146.6 | 2.9 | 14.9 | 164.3 |

| 37 | 2,940 | 2,478 | 44 | 33 | 1,091 | 818 | 152.7 | 3.3 | 16.8 | 172.8 |

| 38 | 3,150 | 2,642 | 43 | 33 | 1,136 | 872 | 159.1 | 3.5 | 18.8 | 181.4 |

| 39 | 3,330 | 2,784 | 42 | 34 | 1,169 | 947 | 163.7 | 3.8 | 20.8 | 188.2 |

| 40 | 3,450 | 2,874 | 40 | 35 | 1,150 | 1,006 | 160.9 | 4.0 | 22.5 | 187.5 |

Extracellular Na content calculated as the product of extracellular Na concentration (140 meq/L) and extracellular mass (volume, 1 g = 1 mL). Intracellular Na content calculated as the product of intracellular Na concentration (4 meq/L) and intracellular mass (volume, 1 g = 1 mL). Bone Na content calculation based on total body calcium content (from Ref. 12) and the molar ratio of calcium to Na in bone of 30:1 (from Ref. 3). Total body Na content calculated as sum of extracellular, intracellular, and bone Na contents. Data derived from Ziegler (12) and Friis-Hansen (2).

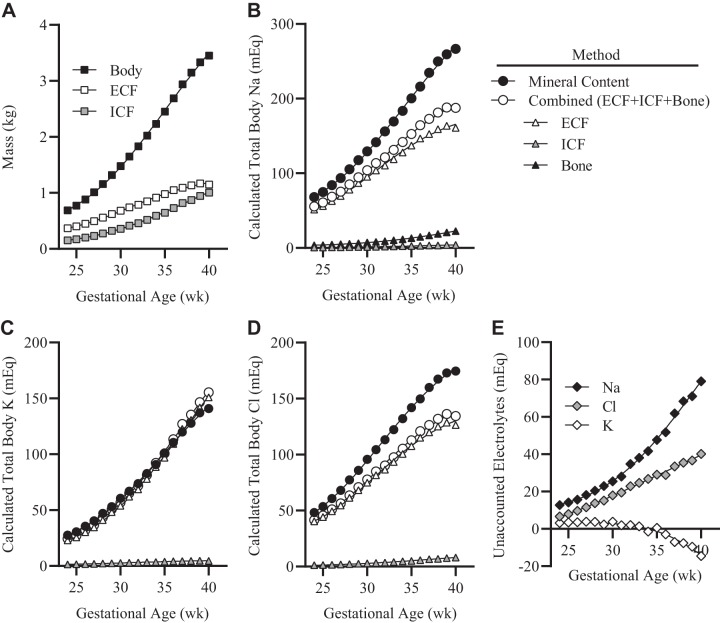

Estimations of accumulated total body K were nearly identical at each gestational time point [<10% variance; (KMC − KBW)/KMC] (Fig. 1A). Estimated total body Cl by MC exceeded that using BW compartments at all time points, with a maximum difference at 40 wk gestation of 40 meq (23% variance) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, total body Na by MC greatly exceeded that calculated based on BW compartments, with differences increasing from 17 meq at 24 wk gestation (variance of 25%) up to 100 meq at 40 wk gestation (variance of 35%) (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Calculated accumulation of total fetal electrolytes with advancing gestational age. A: total body, extracellular fluid (ECF), and intracellular fluid (ICF) masses. B: total sodium content by method and body compartment. C: total potassium content by method and body compartment. D: total chloride content by method and body compartment. E: discrepancy in total body mineral content by method (mineral content method minus body water compartment method).

The disproportionate differences in total body mineral content between the two methods coupled with increasing variances at advancing gestational ages suggest that Na, and to a lesser extent Cl, are stored in osmotically inactive pools within the fetus. These pools increase in size with advancing gestational age. We speculate the fetal osmotically inactive Na pool is vital to maintain a sufficient total body Na content that is necessary for optimal postnatal growth. Mechanisms regulating the mobilization of Na from storage pools during periods of growth and/or sodium depletion have not been well defined, but likely relate in part to compositional changes of the extracellular space/matrix, decreased negative charge density of skin GAGs, and macrophage-driven expansion of lymphatic networks (8, 11). These cutaneous Na pools may additionally strengthen the antimicrobial barrier function of the skin by enhancing macrophage-driven host defense.

Perspectives and Significance

These findings raise questions of whether there are disorders of tissue Na storage during fetal development that may put the infant at increased risk for growth failure or infection during the postnatal period, and whether disorders of water and electrolyte homeostasis during pregnancy may contribute to complications in fetal and postnatal development. For example, our team and others have demonstrated a sustained increase in arginine vasopressin secretion throughout gestation (at least as early as the first trimester) in pregnancies that are eventually complicated by preeclampsia (4, 7), and that chronic infusion of arginine vasopressin is sufficient to model preeclampsia in wild-type C57BL/6J dams including fetal growth restriction (6, 7, 9). Current understanding of the mechanisms, role, and impact of osmotically inactive Na storage pools early in life is completely lacking. However, we hope our novel insights into Na homeostasis during fetal and early postnatal life stimulate further discussion and research in this area.

GRANTS

This work was supported National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL134850 and HL084207 and the American Heart Association Grant 18EIA33890055.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.L.S. and J.L.G. conceived and designed research; J.L.S., C.C.G., and J.L.G. analyzed data; J.L.S., C.C.G., and J.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; J.L.S., C.C.G., and J.L.G. prepared figures; J.L.S. and J.L.G. drafted manuscript; J.L.S., C.C.G., and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.L.S. and J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bischoff AR, Tomlinson C, Belik J. sodium intake requirements for preterm neonates: review and recommendations. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 63: e123–e129, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friis-Hansen B. Water distribution in the foetus and newborn infant. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 72: 7–11, 1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1983.tb09852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison HE. The sodium content of bone and other calcified material. J Biol Chem 120: 457–462, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadli A, Ghosh K, Satoskar P, Damania K, Bansal V, Shetty S. Combination of copeptin, placental growth factor and total annexin V microparticles for prediction of preeclampsia at 10-14 weeks of gestation. Placenta 58: 67–73, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koo WW, Gupta JM. Breast milk sodium. Arch Dis Child 57: 500–502, 1982. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.7.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandgren JA, Deng G, Linggonegoro DW, Scroggins SM, Perschbacher KJ, Nair AR, Nishimura TE, Zhang SY, Agbor LN, Wu J, Keen HL, Naber MC, Pearson NA, Zimmerman KA, Weiss RM, Bowdler NC, Usachev YM, Santillan DA, Potthoff MJ, Pierce GL, Gibson-Corley KN, Sigmund CD, Santillan MK, Grobe JL. Arginine vasopressin infusion is sufficient to model clinical features of preeclampsia in mice. JCI Insight 3: e99403, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santillan MK, Santillan DA, Scroggins SM, Min JY, Sandgren JA, Pearson NA, Leslie KK, Hunter SK, Zamba GK, Gibson-Corley KN, Grobe JL. Vasopressin in preeclampsia: a novel very early human pregnancy biomarker and clinically relevant mouse model. Hypertension 64: 852–859, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafflhuber M, Volpi N, Dahlmann A, Hilgers KF, Maccari F, Dietsch P, Wagner H, Luft FC, Eckardt KU, Titze J. Mobilization of osmotically inactive Na+ by growth and by dietary salt restriction in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1490–F1500, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00300.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scroggins SM, Santillan DA, Lund JM, Sandgren JA, Krotz LK, Hamilton WS, Devor EJ, Davis HA, Pierce GL, Gibson-Corley KN, Sigmund CD, Grobe JL, Santillan MK. Elevated vasopressin in pregnant mice induces T-helper subset alterations consistent with human preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 132: 419–436, 2018. doi: 10.1042/CS20171059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segar DE, Segar EK, Harshman LA, Dagle JM, Carlson SJ, Segar JL. Physiological approach to sodium supplementation in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol 35: 994–1000, 2018. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1632366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiig H, Luft FC, Titze JM. The interstitium conducts extrarenal storage of sodium and represents a third compartment essential for extracellular volume and blood pressure homeostasis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 222: e13006, 2018. doi: 10.1111/apha.13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler EE, O’Donnell AM, Nelson SE, Fomon SJ. Body composition of the reference fetus. Growth 40: 329–341, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]