This cross-sectional study investigates the sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial and professional society boards and compares the publication productivity and number of citations of male vs female board members.

Key Points

Question

Is the sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial and professional society boards representative of US ophthalmologists, and does publication productivity vary between the sexes?

Findings

In this study of 1077 journal editorial and professional society board members, 74.0% were men and 26.0% were women; 92.3% of editors-in-chief or presidents were men, and 7.7% were women. When accounting for career length, no difference in publication productivity was identified.

Meaning

The findings suggest that publication productivity is not associated with election to leadership positions on journal editorial and society boards or with sex.

Abstract

Importance

Because women remain underrepresented in leadership positions in medicine, including ophthalmology, knowledge of sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial and professional society boards seems warranted.

Objectives

To investigate the sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial and professional society boards and compare the publication productivity and number of citations of male vs female board members.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, the SCImago Journal Rank indicator was used to identify the 20 highest-ranked ophthalmology journals. Faculty members from each ophthalmic subspecialty were surveyed within a US academic ophthalmology department to identify 15 influential ophthalmology societies. The 2018 board members of each journal and society were identified from the journals’ and societies’ official websites, and the sex of each individual was recorded. Information regarding journals and societies was collected from October 1 to December 31, 2018. The Scopus database was accessed in January 2019 and then used to find each member’s h-index and m-quotient.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The h-index, defined as the highest number of an author’s publications that received at least h number of citations, was calculated for each board member. The m-quotient, which accounts for varying lengths of academic careers, was calculated by dividing the h-index by the number of years since first publication.

Results

Of the 1077 members of ophthalmic journal editorial and society leadership boards, 797 (74.0%) were men and 280 (26.0%) were women. Among the 24 editors in chief of the 20 journals investigated, 23 (95.8%) were male. Thirteen of the 15 professional society presidents (86.7%) were men. Male board members had significantly higher median h-indexes (male vs female journals: 34 [interquartile range {IQR}, 23-47] vs 28 [IQR, 19-40], P < .001; male vs female societies: 27 [IQR, 15-41] vs 17 [IQR, 8-32], P = .006), median publication numbers (male vs female journal board members: 157 [IQR, 88-254] vs 109 [IQR, 66-188], P < .001; male vs female society board members: 109 [IQR, 57-190] vs 58 [IQR, 28-139, P = .001), and median citations (male vs female journal board members: 4027 [IQR, 1897-8005] vs 2871 [IQR, 1344-5852], P < .001; male vs female society board members: 2228 [IQR, 1005-5069] vs 1090 [IQR, 410-2527], P = .003). However, the median m-quotients for male and female board members were comparable (male vs female journal board members: 1.2 [IQR, 0.8-1.6] vs 1.1 [IQR, 0.8-1.5], P = .54; male vs female society board members: 1.0 [IQR, 0.7-1.4] vs 0.9 [IQR, 0.6-1.3], P = .32).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that the sex composition on journal editorial and professional society boards in ophthalmology is consistent with the sex composition of ophthalmologists in the US, as reported by the Association of American Colleges, but that editor in chief and society president positions are male dominated despite the apparent equality in academic productivity.

Introduction

Women physicians face a unique set of challenges within the medical field, ranging from subconscious and implicit bias to sex disparities in pay and promotion to leadership positions. Understanding the role that sex inequality plays within the field of ophthalmology is essential to changing the current landscape.

Women make up a quarter (25.3%) of ophthalmologists in the US and comprise 28.0% of academic ophthalmology faculty members.1,2,3 However, a previous study1 found that women are disproportionately underrepresented in ophthalmology leadership positions. In 2007, only 4% of academic chair positions were held by women,4 and a more recent study in 2018 by Dotan et al5 revealed an increase to only 10%. Similar disparities exist across academic ranks, with 13% of women and 34% of men achieving full professorship.6 One might hypothesize that these disparities are the result of a history of sex disparities among medical school graduates and that current leadership demographics are attributable to sex disparities from 20 years ago. Thus, to better evaluate current sex inequalities, it might make more sense to study sex differences in leadership positions that have a higher turnover rate, such as those of journal editorial and professional society boards.

Although there are no published studies, to our knowledge, on the sex composition of leadership boards of ophthalmic professional societies, there are a few reports7,8 on sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial boards. In 2001, Kennedy et al7 reported that the proportion of editorial board members of Ophthalmology who were women was 15.4%, which was similar to the proportion of ophthalmologists in the US who were women at that time (13.4%). Ten years later, Amrein et al8 came to a similar conclusion, reporting that the editorial boards of 5 ophthalmology journals included 21.1% women, which was slightly greater than the proportion of ophthalmologists in the US who were women at that time (17.0%). These studies were limited in that the largest of them included data from only 5 journals. In addition, none of these studies investigated the association between sex and academic productivity and appointment to an editorial board position.

To analyze academic productivity, Hirsch9 proposed the h-index, which is defined as the highest number of publications that a person attains with at least the same number of citations. Using the h-index, Lopez et al6 previously reported that women surpass men in scholarly productivity during later stages of their careers, yet they continue to be underrepresented in senior faculty positions. The authors concluded that women have low scholarly influence during earlier career stages, which may impede academic advancement.6 The purpose of the current study was to investigate the sex composition of ophthalmic journal editorial and professional society boards and compare the publication productivity and number of citations of male vs female board members.

Methods

This cross-sectional study received a nonhuman research notification by the institutional review board of the Penn State College of Medicine; therefore, informed consent was not required. The SCImago Journal Rank indicator was used to determine the 20 highest-ranked ophthalmology journals.10 The 2018 editorial board members of each journal were identified from the journal’s official website. The sex of individuals in editorial board leadership positions was recorded. Using an unvalidated survey, faculty members who represented each ophthalmic subspecialty were surveyed at a US academic ophthalmology department (Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania) to identify 15 influential ophthalmology societies. The board of directors was identified from each society’s official website, and the sex of each individual was recorded. Information regarding journals and societies was collected from October 1 to December 31, 2018.

The Scopus database was accessed in January 2019 to determine each board member’s h-index. Each board member’s m-quotient, which accounts for varying lengths of academic careers, was calculated by dividing the h-index by the number of years between the date of first publication and December 2018. Scopus was also used to determine the total number of publications by each board member. The total number of times that an individual author’s articles were cited was also obtained using the Scopus database.

Confirmation of sex was accomplished through online searches with photographs, profiles, or sex-indicating pronouns. Attempts were made to determine any alternative names that faculty members had used before their current name. Online searches of curriculum vitae searches and Scopus website profiles were performed to include publications under different last names (eg, maiden names) for each board member.

Statistical Analysis

All variables were summarized before analysis with frequencies and percentages or means (SDs) and medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs], and the compositions of continuous variables were assessed using histograms and normal probability plots. Categorical variables were compared by sex using χ2 tests and percentages, whereas continuous variables were compared between sexes using Wilcoxon rank sum tests and medians. These comparisons were made overall and within journal and society subgroups. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P = .05. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

General Characteristics

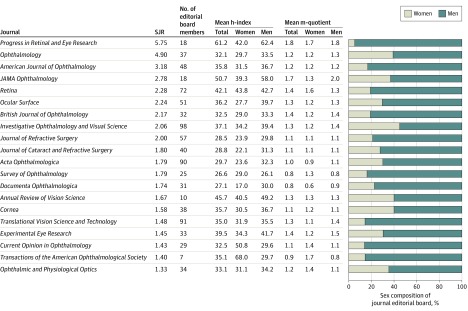

The journals and ophthalmic societies surveyed are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Information on a total of 1114 board members was collected from 20 journals and 15 societies. Thirty-seven individuals were excluded from analyses because there was insufficient information on the journal and society websites to identify the individual or to complete all biographic data collection, leaving a total of 1077 individuals. The demographic information and comparative statistics for these individuals are given in the Table. Overall, 810 (74.0%) were men and 280 (26.0%) were women. Of the members for whom geographic information could be collected, 711 (66.1%) were located in the US. Of these, 615 (56.9%) were affiliated with US academic institutions, 41 (3.8%) were affiliated with US nonacademic hospitals or research centers, and 55 (5.1%) were affiliated with a private practice. The other 365 (33.9%) were in hospitals or research centers outside the US. A higher proportion of individuals on society boards held an MD degree compared with journal editorial boards (187 [86.2%] vs 412 [48.3%]; P < .001), and a higher percentage of PhD (226 [26.5%] vs 10 [4.6%]) and MD/PhD (215 [25.2%] vs 20 [9.2%]; P < .001) degrees were held by individuals on journal boards compared with society boards (Table).

Figure 1. Sex Composition of the 20 Highest-Ranked Ophthalmology Publications.

SJR indicates SCImago journal rank.

Figure 2. Sex Composition of the 15 Ophthalmology Societies Studied.

Table. Characteristics of Journal and Society Board Members by Sex.

| Characteristic | Journal | P value | Society | P value | Journal vs society P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | ||||

| Board members | |||||||||

| Board leadership, No./total No. (%) | 24/24 (100) | 23/24 (95.8) | 1/24 (4.2) | .20 | 15/15 (100) | 13/15 (86.7) | 2/15 (13.3) | .25 | .004 |

| All members, No./total No. (%) | 859/859 (100) | 639/859 (74.4) | 220/859 (25.6) | 218/218 (100) | 158/218 (72.5) | 60/218 (27.5) | .60 | ||

| Degree type, No. (%) | |||||||||

| MD | 412 (48.3) | 335 (52.9) | 77 (35.0) | <.001 | 187 (86.2) | 141 (89.8) | 46 (76.7) | .04 | <.001 |

| PhD | 226 (26.5) | 153 (24.2) | 73 (33.2) | 10 (4.6) | 5 (3.2) | 5 (8.3) | <.001 | ||

| MD/PhD | 215 (25.2) | 145 (22.9) | 70 (31.8) | 20 (9.2) | 11 (7.0) | 9 (15.0) | <.001 | ||

| Location, No. (%) | |||||||||

| US | 504 (58.7) | 376 (58.9) | 128 (58.2) | .85 | 207 (95.0) | 151 (95.6) | 56 (93.3) | .74 | <.001 |

| Outside the US | 354 (41.3) | 262 (41.1) | 92 (41.8) | 11 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) | 4 (6.7) | <.001 | ||

| Career path of US members, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Academic | 448 (88.9) | 330 (87.8) | 118 (92.2) | .15 | 167 (80.7) | 118 (78.1) | 49 (87.5) | .14 | <.001 |

| Nonacademic | 56 (11.1) | 46 (12.2) | 10 (7.8) | 40 (19.3) | 33 (21.9) | 7 (12.5) | <.001 | ||

| Years in publishing, median (IQR) | |||||||||

| Board leaders | 39 (29-44) | 38 (28-44) | 40 | .83 | 30 (23-36) | 30 (24-36) | 25 (20-30) | .35 | .02 |

| General board | 30 (22-37) | 31 (22-38) | 26 (20-34) | <.001 | 27 (20-33) | 28 (22-33) | 22 (12-32) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Publication measures | |||||||||

| Board leadership h-index, median (IQR) | 42 (34-60) | 42 (34-56) | 68 | .19 | 31 (18-37) | 31 (19-36) | 25 (6-44) | >.99 | .003 |

| Board h-index, median (IQR) | 33 (23-45) | 34 (23-47) | 28 (19-40) | <.001 | 25 (14-38) | 27 (15-41) | 17 (8-32) | .006 | <.001 |

| Board leadership m-quotient, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.1 (1.0-1.5) | 1.7 | .25 | 0.8 (0.7-1.2) | 0.8 (0.7-1.2) | 1.2 (0.2-2.2) | >.99 | .03 |

| Board m-quotient, median (IQR) | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | .54 | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | .32 | <.001 |

| Publications, median (IQR), No. | 144 (79-234) | 157 (88-254) | 109 (66-188) | <.001 | 95 (42-165) | 109 (57-190) | 58 (28-139) | .001 | <.001 |

| Citations, median (IQR), No. | 3737 (1744-7218) | 4027 (1897-8005) | 2871 (1344-5852) | <.001 | 1832 (799-4743) | 2228 (1005-5069) | 1090 (410-2527) | .003 | <.001 |

Career duration of individuals varied across journal editorial and society boards (Table). The median career duration of the editors in chief was longer than that of the society board presidents (39 years [IQR, 29-44 years] vs 30 years [IQR, 23-36 years]; P = .02). Similarly, the median career duration of the general journal editorial board members was longer than that of the society board members (30 years [IQR, 22-37 years] vs 27 years [IQR, 20-33 years]; P < .001).

Board Composition

Of the journal editorial board members, 220 (25.6%) were women, and of society board members, 60 (27.5%) were women (P = .56) (Table). No significant difference was found in sex composition between journal editorial and professional society boards. The sex composition of the journal and society boards is given in eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement.

A total of 24 editors in chief were identified for the 20 ophthalmology journals investigated; 23 (95.8%) were men compared with 1 woman (4.2%) (P = .02) (Table). Fifteen society presidents were identified; of these, 13 (86.7%) were men and 2 (13.3%) were women (P = .25). No statistically significant difference was found between the median journal impact factor (median impact factor: men, 1.8 [IQR, 1.6-2.2]; women, 2.0 [IQR, 1.7-2.2]; P = .32) or society board size (median board size: men, 1400 [IQR, 686-6700]; women, 786 [IQR, 531-6700]; P = .13) and the sex composition among board members.

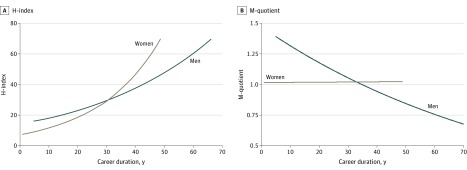

Publication Productivity and Number of Citations

The median h-index for male journal editorial board members was significantly higher than that for women (34 [IQR, 23-47] for men vs 28 [IQR, 19-40] for women; P < .001) (Table). Similarly, the median h-index for male society board members was significantly higher than that for women (27 [IQR, 15-41] vs 17 [IQR, 8-32]; P = .006). Among journal editorial board members and society board members, men had median longer publication records than women (editorial board: men, 31 years [IQR, 22-38 years]; women, 26 years [IQR, 20-34 years]; society board: men, 28 years [IQR, 22-33 years]; women, 22 years [IQR, 12-32 years]; P < .001 for both). No significant difference was found between the m-quotients of male and female journal board members (median: 1.2 [IQR, 0.8-1.6] vs 1.1 [IQR, 0.8-1.5]; P = .54) or society board members (median: 1.0 [IQR, 0.7-1.4] vs 0.9 [IQR, 0.6-1.3]; P = .32). However, the h-index increased more slowly over time for men than for women; m-quotients decreased for men and remained stable for women over time (Figure 3). Male board members had significantly higher median publication numbers (male vs female journal board members: 157 [IQR, 88-254] vs 109 [IQR, 66-188], P < .001; male vs female society board members: 109 [IQR, 57-190] vs 58 [IQR, 28-139, P = .001) (Table). Similarly, male board members had significantly higher median citations (male vs female journal board members: 4027 [IQR, 1897-8005] vs 2871 [IQR, 1344-5852], P < .001; male vs female society board members: 2228 [IQR, 1005-5069] vs 1090 [IQR, 410-2527], P = .003) (Table)

Figure 3. Comparison of Sex and Publication Range and Influence Measured by h-Indexes and m-Quotients in Ophthalmology Journals and Society Boards.

Career duration was measured by years since first publication for each author. The h-index and m-quotient for men tended to increase earlier in their careers, whereas the h-index and m-quotient for women increased faster than those for men at approximately 30 years and continued to surpass those for men for the remainder of their career lengths.

The 23 male editors in chief had a median h-index of 42 (IQR, 34-56) and the 1 female editor in chief an h-index of 68.0 (P = .19) (Table). No differences in median years in publishing existed among male and female editors in chief (38 years [IQR, 28-44 years] vs 40 years; P = .83) or society presidents (30 years [IQR, 24-36] vs 25 [IQR, 20-30]; P = .35).

The 23 male editors in chief had a median m-quotient of 1.1 (IQR, 1.0-1.5), and the 1 female editor in chief had an m-quotient of 1.7 (P = .25). Among society presidents, the 13 men had a median h-index of 31 (IQR, 19-36), and the 2 women had a median h-index of 25 (IQR, 6-44) (P > .99). The 13 male society presidents had a median m-quotient of 0.8 (IQR, 0.7-1.2), and the 2 female presidents had a median m-quotient of 1.2 (IQR, 0.2-2.2) (P > .99).

A total of 164 individuals accounted for 346 of the 1077 entries (32.1%) included in this study; in other words, these individuals appeared on more than 1 society or journal board (250 men [31.4%] and 96 women [34.3%]). Individuals who were on more than 1 board had a higher h-index and m-quotient than individuals on a single board (median h-index: 39 [IQR, 28-52] vs 28 [IQR, 18-40]; median m-quotient: 1.3 [IQR, 1.0-1.7] vs 1.0 [IQR, 0.7-1.4]; P < .001 for both). When comparing sex within this subgroup, men had higher median h-indexes than women (42.0 [IQR, 29-54] vs 34.0 [IQR, 26-45]; P = .007), but there was no difference in median m-quotient (1.3 [IQR, 1.0-1.7] vs 1.3 [IQR, 1.0-1.7]; P = .94).

Discussion

Previous studies7,8,11 have compared the editorial boards of only the top 5 ophthalmology journals with editorial boards in other medical subspecialties and reported that the demographic of editorial boards matches closely with that of practicing ophthalmologists. To our knowledge, the current investigation is the largest study to date on the sex composition of journal editorial boards and the first study, to our knowledge, on sex composition of professional society boards within ophthalmology. It is also the first study, to our knowledge, to evaluate these data in the context of academic productivity.

We found that the proportion of female journal (25.6%) and society (27.5%) board members in 2018 was similar to the proportion of women ophthalmologists in the US at that time (25.3%).2 Women comprise more than half (50.9%) of medical school graduates today but comprised only 42.4%, 30.8%, and 16.2% just 20, 30, and 49 years ago, respectively.12,13 Thus, the sex disparity within ophthalmology and on leadership boards in ophthalmology may be, at least in part, associated with sex disparities in past decades. In 2017, more than 41% of residents entering ophthalmology were women; thus, one might expect that the sex disparities continue to neutralize.2

Of interest, of the 20 highest-ranked ophthalmic journals, only 1 had a female editor in chief (4.2%). Similarly, women were less likely to hold the position of society president; of the 15 ophthalmic societies analyzed, only 2 had female presidents (13.3%). The career duration (measured by years since first publication) was a mean of 9.5 years longer for editors in chief and 3.0 years longer for presidents compared with the general board. The single female editor in chief had a higher h-index and m-quotient than her 23 male counterparts. The m-quotient for the 2 female society presidents was higher than that for their 13 male counterparts, but this limited data set does not allow for conclusions about whether higher productivity on the part of women is a requirement to achieve the same level of leadership.

The h-index of male journal editorial and society board members was statistically higher compared with female members; however, in both groups, no statistically significant difference was found between the m-quotients of men and women. These findings suggest that, although women as a group have lower productivity numbers than men, when length of academic careers is considered, the 2 groups are similar. As the duration of female ophthalmologists’ careers increases, the median h-index for women may become more similar to that for men. Several previous studies6,14,15 have indicated that female academic physicians attain higher scholarly influence later in their careers compared with male colleagues. A study by Lopez and colleagues6 found that male ophthalmologists tend to have increased publication numbers in the beginning of their career, whereas the publication numbers for female ophthalmologists increases faster than men later in their career. Similarly, we found that men in leadership board positions had greater scholarly influence in the beginning of their careers compared with female board members who surpassed their male colleagues in the later stages of their career (Figure 3). Studies6,15,16 in other medical fields have found similar results and have noted that this may be associated with women bearing greater family responsibility early during their career.

There is a well-known pipeline problem in ophthalmology. The mean career duration was 39 years for journal editors in chief and 30 years for society presidents. Although women currently comprise a quarter of all ophthalmologists, 30 to 37 years ago, this proportion was approximately 7.5%.17 The qualified applicants for these top leadership positions have similar career durations and represent a smaller cohort of women within similar career timelines. Although many studies1,6 have described this pipeline problem within ophthalmology, others have demonstrated the increase in the number of women entering ophthalmology; however, there appears to be a lack of corresponding increase in women in leadership positions.

Although this study did not investigate the specific reasons why a discrepancy exists in the representation of women on journal and society boards, there are several reasons we can consider when attempting to better understand the disparity. The ophthalmology community has little information regarding each journal’s and society’s selection of board members and election of an editor in chief or president. If an application process exists, it is possible that women applied for these positions less often or were less often encouraged to apply. If these positions are appointed without an application process, it is possible that fewer women were considered because of their shorter career lengths. It is unlikely that boards look at academic productivity alone when electing their members. We speculate that other experiences and leadership qualities are likely taken into consideration along with an individual’s history of scholarship.

Looking ahead, the presidents of most societies change every 1 to 2 years, whereas the editors in chief of most journals serve longer tenures. Thus, it is possible that the sex distribution among society presidents may foreshadow trends within the field; the higher proportion of female presidents in societies may foretell a trend toward more female editors in chief in 10 or 20 years as lengths of academic careers and the proportion of female ophthalmologists also increase. In addition, if journals and societies want their boards to be representative of the current demographics of the field, one way to do so might be to create positions for early-career individuals. These early-career positions may give women greater opportunity to fill these leadership positions.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although previous studies7,8 have investigated academic journals, this was the first study, to our knowledge, to include the investigation of ophthalmic societies. As such, no protocol has been established with regard to selecting ophthalmic societies. In the present study, an unvalidated selection process was used, which consisted of surveying faculty from a single academic ophthalmology department. It is possible that if more academic ophthalmologists were surveyed or the survey was repeated in a different group, different societies would have been included in the analysis.

Non–US-based editorial and society board members were included in our analysis but were subsequently compared with normative data on the sex distribution of US-based ophthalmologists only. This approach was taken because, to our knowledge, there are no published data on the sex distribution of ophthalmologists worldwide. The proportion of women who are ophthalmologists worldwide varies greatly across regions, and the comparison with US-based normative data is only one way of providing context; it is not the complete picture.

Indexes of scholarly productivity, including the h-index and m-quotient, have limitations, such as lack of accuracy, validity, and applicability. This study used the Scopus database for the calculation of the h-index and m-quotient. It is possible that scholarly publications, primarily those not included in the PubMed database, are not accounted for in Scopus author searches. A recent study18 found wide variations in the h-index when reviewing author profiles depending on whether Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, or Research Gate is used. Limitations of the h-index include the possible influence of self-citation, inclusion of articles that are widely criticized or noteworthy for inaccurate conclusions, biases toward higher h-indices for older publications and researchers, and inherent limitations of highly influential articles not getting enough recognition.18 This study also used the m-quotient to eliminate the inherent bias in the h-index toward older scholarly activity and researchers. Multi-author publications contain inherent differences in the amount of contribution from each author. Future studies could consider using revised h-indices that account for the author’s listing on a publication, such as first or last author compared with an author listed in the middle of the byline. The researchers in this study assigned sex based on binary categorical measures male and female based on photographs, names, and sex pronouns. The binary sex categories used may be different from how individuals may have self-reported their sex.19,20 In addition, our study cannot infer causality.

Conclusions

The results of our study suggest that, in addition to the sex disparities among ophthalmology department chairs and senior academic faculty, which have been reported previously, persistent sex disparities in ophthalmic leadership positions exist. The findings also revealed an association between publication productivity and sex within leadership positions in journals and societies.

eTable 1. Gender Composition of the 20 Ophthalmology Journals Studied

eTable 2. Gender Composition and Size of the Ophthalmology Societies Studied

References

- 1.Shah DN, Volpe NJ, Abbuhl SB, Pietrobon R, Shah A. Gender characteristics among academic ophthalmology leadership, faculty, and residents: results from a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(1):1-6. doi: 10.3109/09286580903324892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Colleges . Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty. Published 2018. Accessed April 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492560/1-3-chart.html.

- 3.Thiessen CR, Venable GT, Ridenhour NC, Kerr NC. Publication productivity for academic ophthalmologists and academic ophthalmology departments in the United States: an analytical report. J Clin Acad Ophthalmol. 2016;8(01):e19-e29. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz OA, Johnson NB, Thomas SM. Twenty-five years of leadership: a look at trends in tenure and appointments of chairs of ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(4):807-811. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dotan G, Qureshi HM, Gaton DD. Chairs of United States academic ophthalmology departments: a descriptive analysis and trends. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;196:26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez SA, Svider PF, Misra P, Bhagat N, Langer PD, Eloy JA. Gender differences in promotion and scholarly impact: an analysis of 1460 academic ophthalmologists. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):851-859. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy BL, Lin Y, Dickstein LJ. Women on the editorial boards of major journals. Acad Med. 2001;76(8):849-851. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200108000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amrein K, Langmann A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Pieber TR, Zollner-Schwetz I. Women underrepresented on editorial boards of 60 major medical journals. Gend Med. 2011;8(6):378-387. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569-16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrero-Bote VP, Moya-Anegón F. A further step forward in measuring journals’ scientific prestige: the SJR2 indicator. J Informetrics. 2012;6(4):674-688. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2012.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansour AM, Shields CL, Maalouf FC, et al. Five-decade profile of women in leadership positions at ophthalmic publications. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(11):1441-1446. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges . The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. Published 2016. Accessed April 2019. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/.

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges . Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, McClees M, Lindor KD. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):43-47. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff9ff2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Cherla DV, et al. Gender disparities in research productivity among 9952 academic physicians. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):1865-1875. doi: 10.1002/lary.24039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ. 2001;35(2):139-147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Medical Association . Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the United States. American Medical Association; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martín-Martín A, Orduna-Malea E, Thelwall M, López-Cózar ED. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J Informetrics. 2018;12(4):1160-1177. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2018.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser G. Evaluating inclusive gender identity measures for use in quantitative psychological research. Psychol Sex. 2018;9(4):343-357. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2018.1497693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond M. Sex and gender are different: sexual identity and gender identity are different. Clin Child Psychol P. 2002;7(3):320-334. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007003002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Gender Composition of the 20 Ophthalmology Journals Studied

eTable 2. Gender Composition and Size of the Ophthalmology Societies Studied