Abstract

Recent evidence has shown that auditory information may be used to improve postural stability, spatial orientation, navigation, and gait, suggesting an auditory component of self-motion perception. To determine how auditory and other sensory cues integrate for self-motion perception, we measured motion perception during yaw rotations of the body and the auditory environment. Psychophysical thresholds in humans were measured over a range of frequencies (0.1–1.0 Hz) during self-rotation without spatial auditory stimuli, rotation of a sound source around a stationary listener, and self-rotation in the presence of an earth-fixed sound source. Unisensory perceptual thresholds and the combined multisensory thresholds were found to be frequency dependent. Auditory thresholds were better at lower frequencies, and vestibular thresholds were better at higher frequencies. Expressed in terms of peak angular velocity, multisensory vestibular and auditory thresholds ranged from 0.39°/s at 0.1 Hz to 0.95°/s at 1.0 Hz and were significantly better over low frequencies than either the auditory-only (0.54°/s to 2.42°/s at 0.1 and 1.0 Hz, respectively) or vestibular-only (2.00°/s to 0.75°/s at 0.1 and 1.0 Hz, respectively) unisensory conditions. Monaurally presented auditory cues were less effective than binaural cues in lowering multisensory thresholds. Frequency-independent thresholds were derived, assuming that vestibular thresholds depended on a weighted combination of velocity and acceleration cues, whereas auditory thresholds depended on displacement and velocity cues. These results elucidate fundamental mechanisms for the contribution of audition to balance and help explain previous findings, indicating its significance in tasks requiring self-orientation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Auditory information can be integrated with visual, proprioceptive, and vestibular signals to improve balance, orientation, and gait, but this process is poorly understood. Here, we show that auditory cues significantly improve sensitivity to self-motion perception below 0.5 Hz, whereas vestibular cues contribute more at higher frequencies. Motion thresholds are determined by a weighted combination of displacement, velocity, and acceleration information. These findings may help understand and treat imbalance, particularly in people with sensory deficits.

Keywords: auditory motion, motion perception, multisensory integration, perceptual threshold, vestibular

INTRODUCTION

Auditory contributions to balance and motion perception.

Visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive inputs are well known to contribute to maintaining balance and orientation, but there is a growing body of behavioral evidence showing that balance function can be improved with external sound cues. This has been shown for static balance (Stevens et al. 2016), moving balance (Zhong and Yost 2013), orientation (Gandemer et al. 2017), and navigation (Genzel et al. 2018). Expanding on these reports, recent evidence has also shown that individuals with hearing impairment have better balance when wearing their hearing aids and cochlear implants (Hallemans et al. 2017; Shayman et al. 2017, 2018a). Like visual cues, the location and motion of auditory sources relative to an observer are hypothesized to serve as external reference points that enhance self-motion perception based on vestibular cues (Karim et al. 2018; Yost et al. 2015).

Mechanisms of auditory-vestibular combination and outstanding questions.

Neurons carrying a combination of auditory and vestibular signals are found in the dorsal cochlear nucleus, relatively early within the auditory pathway (Wigderson et al. 2016). Other evidence for auditory-vestibular integration is provided by specialized neurons in the auditory cortex tuned to differentiate egocentric (self) from allocentric (external source) frames of reference (Town et al. 2017). Behavioral evidence shows that the vestibular and auditory systems work together to localize sound sources during movement (Genzel et al. 2016, 2018; Van Barneveld and Van Opstal 2010; Yost et al. 2015). The key parameters governing the contributions of auditory input for self-motion perception are not yet known. One such parameter is the sensitivity for relative motion between a listener and an auditory source, a calculation that is necessary for an auditory source to function as an environmental spatial reference point. However, it is not known under which range of motions auditory and vestibular information are combined to provide meaningful benefit over either one alone. Finally, given evidence for the integration of auditory and vestibular sensory information, it is reasonable to inquire about the mathematical basis of their combination.

Methodology and framework.

Psychophysical techniques, including signal detection theory (Macmillan and Creelman 2005), offer a mathematically rigorous method for answering outstanding questions of relative unisensory perceptual precision, particularly within the auditory (Hirsh and Watson 1996) and vestibular systems (Merfeld 2011). Studies involving multisensory perception have also demonstrated the utility of this framework, allowing precise statistical hypotheses to be compared with experimental results. This model has been used in studies involving vestibular-visual pairs to improve our understanding of spatial integration (Fetsch et al. 2007, 2010; Gu et al. 2008; Kaliuzhna et al. 2018; Karmali et al. 2014). In the present study, by measuring perceptual motion-detection thresholds, we were able to address outstanding questions in the auditory and vestibular systems by using the following three-stimulus paradigm: vestibular motion cues involving stimulation of the horizontal semicircular canal, vestibular and earth-fixed auditory cues, and auditory motion cues. Additionally, the vestibular and earth-fixed auditory paradigm was investigated in conditions allowing either monaural or binaural auditory cues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants.

Seven healthy volunteers [3 female, 4 male; age 31.86 ± 9.69 (SD) years] formed a sample of convenience. Participants had no known history of dizziness, vertigo, color blindness, or musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or neurological problems. They were screened for motion sickness susceptibility and completed pure tone audiometry. All participants had normal hearing thresholds (<15 dB HL) between 0.25 and 8 kHz. Thresholds did not differ by more than 10 dB HL between ears. All participants gave written, informed consent before testing. The study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board and followed ethical standards advised in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conditions.

All participants completed 16 threshold tests consisting of four sensory conditions at four frequencies of rotation (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 Hz). The sensory conditions included the following: 1) head rotation about an earth-vertical axis with head-fixed masking sound (vestibular unisensory condition, primarily stimulating the horizontal semicircular canals), 2) fixed-head position with a sound source rotating in the yaw plane about the head (auditory unisensory condition), 3) head rotation with earth-fixed sound source with auditory spatial cues afforded by binaural hearing (vestibular and binaural auditory multisensory condition), and 4) head rotation with earth-fixed sound source in which participants were acutely unilaterally deafened with unilateral ear plug and earmuff (vestibular and monaural auditory multisensory condition). Conditions were pseudorandomized, and, as each test averaged 30 min and 24 trials (total 6 h of testing), testing was split into two to three, 90- to 120-min visits. Participants were encouraged to take breaks in between tests to minimize fatigue. Before each test, participants were conditioned to the task with ample practice.

Sound stimuli.

Sound stimuli consisted of a continuous train of 0.25-ms bursts, each of which was created by windowing a 2-kHz tone with a raised-cosine envelope 0.25 ms in duration. The window was applied to the same phase of the tone for each click (window time zero aligned with time zero of the sine wave, i.e., the window starts at the first zero-crossing of the tone before the rising pressure), resulting in windowed positive half-waves, and thus identical bandwidth and phase information for each click. The advantage of applying the window in this way is that it restricts the energy of the click into the audible range, and the bandwidth is controlled by varying the window duration. Sounds were generated at a sampling rate of 100 kHz and downsampled to 44.1 kHz for presentation. This processing resulted in a brief click with equal energy in the frequency region between 20 Hz and 6 kHz, with a decrease of energy of 5 dB for every successive increase of 3 kHz. The stimuli were generated as a 25-min .wav file, with an average spacing between clicks of 50 ms, but each click onset time was randomly increased or decreased by 12.5 ms. This train of bursts with onset randomization was employed to discourage adaptation and habituation processes by the spatial auditory system, which is known to respond more robustly to intermittent rather than constant stimuli (Brown and Stecker 2010). The speaker (frequency response of 0.1 to 22.0 kHz, Model R1; YC Cable, Ontario, CA), was calibrated to 60-dB sound pressure level (SPL). In the spatial auditory conditions, the sound stimulus was presented continuously.

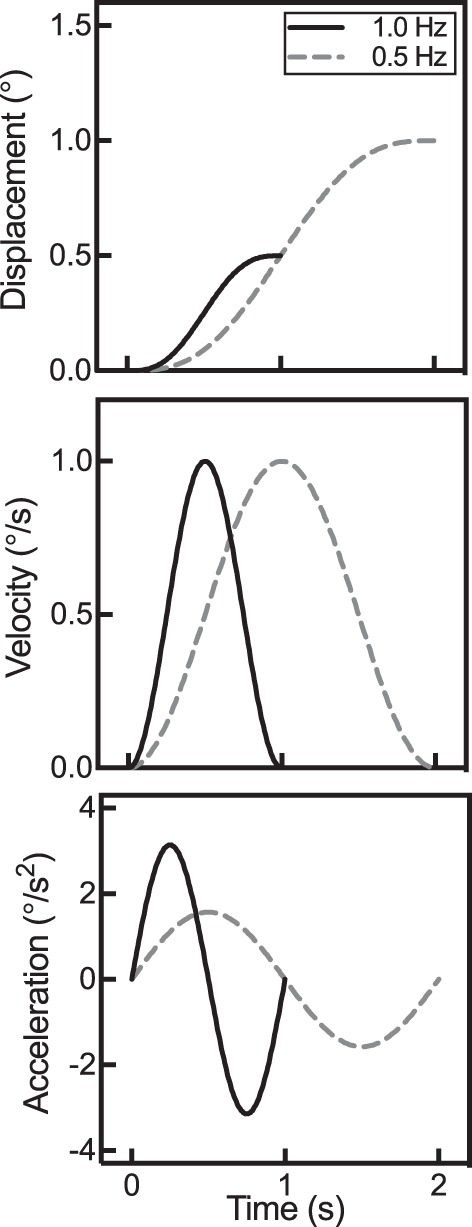

Motion stimuli.

All yaw-rotation motion profiles were generated by custom-written software in MATLAB 2015a (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and delivered to velocity servo-controlled motors via a custom LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX) real-time program at sample rates of 200/s. Motion profiles consisted of single-cycle raised cosine velocity waveforms with frequencies of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 Hz. (Fig. 1). After each motion stimulus, participants were cued with an LED indicator to respond verbally stating the direction of their perceived motion, and the experimenter coded the response into a spreadsheet. After participants responded, they were brought back to the starting position using an equivalent but opposite stimulus trajectory to cancel out any potential effect of velocity storage. An independent inertial measurement device (APDM, Portland, OR) was used to verify that the motor was produced for the correct motion profile.

Fig. 1.

Whole body and speaker yaw-axis rotation trajectories at 2 frequencies of motion, 1.0 and 0.5 Hz (0.2 and 0.1 Hz were also tested, but not pictured here). Stimuli at various frequencies may have the same peak velocity, but other parameters, such as stimulus duration, peak displacement, and peak acceleration, covary with frequency.

Equipment.

Vestibular rotational motion stimuli were delivered using a custom-built velocity servo-controlled DC motor (160 N-m peak torque; Inland Motors, Radford, VA) that rotated participants seated in a chair about an earth-vertical axis. Auditory rotational motion stimuli were delivered by a speaker mounted on a custom-built sonic boom arm that was attached to a velocity servo-controlled motor (EG&G Torque Systems, Watertown, MA) mounted above the participant whose rotation axis was aligned with the rotational chair axis. A five-point harness, memory foam padding, headrest, and head strap secured participants into the rotary chair in an upright position with each participant’s head oriented with Reid’s plane 20° nose down, bringing the horizontal canals into an earth-horizontal orientation (Della Santina et al. 2005). Each participant’s head was centered on the yaw axis of rotation. Participants wore light-proof goggles that contained two LED indicators used for cueing. All experiments were performed in the dark to minimize unintended sensory input.

For the two earth-referenced sound conditions, the speaker was mounted at ear level 1 m in front of the participant at 0° in the azimuth plane on the boom arm. For the unilateral sound condition, the set-up was the same with the addition of a unilateral, left-sided ear plug (3M, St. Paul, MN) [33-dB noise reduction rating (NRR)] and earmuff (L3 Howard Leight, Smithfield, RI) (30-dB NRR) for a combined 63-dB attenuation. In the head rotation with head-fixed masking sound condition, white noise (60 dB SPL) was provided through ear buds (Apple, Cupertino, CA) under bilateral ear muffs (L3 Howard Leight, Smithfield, RI) (30-dB NRR).

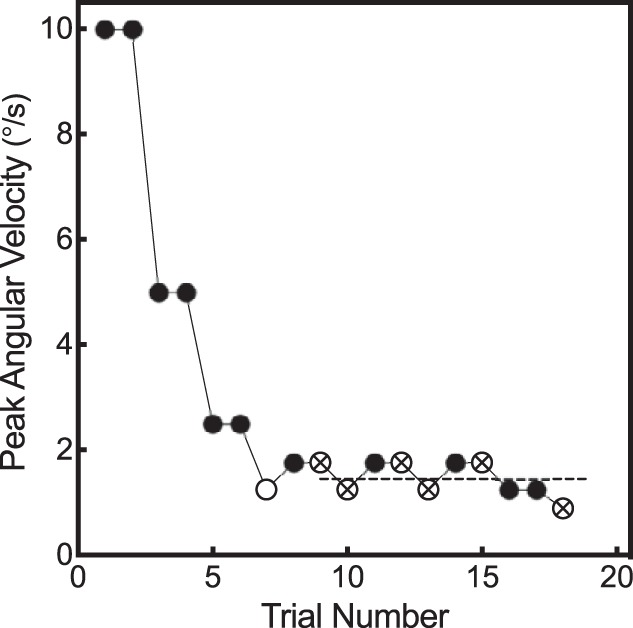

Adaptive threshold tracking.

Thresholds were measured adaptively using a two-down, one-up staircase procedure, targeting a threshold (T70.7%) at which the observer correctly detects motion 70.7% of the time (Levitt 1971). T70.7% thresholds can be converted to the standard deviation of the physiological noise (σ) by using the following formula: T70.7% = 0.54σ (Merfeld 2011). All measurements were originally made in the velocity domain, as vestibular psychophysical experiments have traditionally made threshold measurements in terms of peak angular velocity (°/s). Each staircase started at an angular velocity of 10.0°/s, which was much higher than any participant’s yaw rotational detection threshold. Following two consecutive correct reports of rotation direction, the stimulus amplitude was divided by a factor of two. Following the first reversal (i.e., incorrect report of rotation direction), the stimulus size was increased by a factor of √2. Trials continued until each test demonstrated seven direction reversals in the adaptive track. Threshold was defined as the mean of the last six reversals (Fig. 2). To maintain the alertness of the participants, open-ended questions were asked every 5–10 trials. See Karmali et al., 2016 for a review of psychophysical methodology for determining motion perception thresholds (Karmali et al. 2016).

Fig. 2.

Adaptive perceptual threshold tracking. A representative tracing is shown for the vestibular-only condition at 0.5 Hz. Each circle indicates 1 trial in which the participant had to identify the direction (right or left) in which they perceived motion. Testing began at 10°/s, a suprathreshold angular velocity, and was reduced in a 2-down-1-up manner. 2 consecutively correct responses led to a decreased stimulus amplitude, and 1 incorrect response increased the amplitude of the following stimulus. Each test continued until there were 7 reversals in the adaptive track. Reversals are defined as a trial in which a directional change in the track occurred. Open circles denote reversals, and open circles with crosses indicate the last 6 reversals that were averaged to determine an individual perceptual threshold (dashed line).

Optimal integration predictions.

Predicted Bayesian optimal integration thresholds were calculated for each participant using their vestibular and auditory unisensory thresholds (Eq. 1) as described previously (Karmali et al. 2014):

| (1) |

where σ2vestibular, σ2auditory, σ2vestibular + auditory are the estimated variances of the distributions of internal perceptual representations encoding motion afforded by vestibular, auditory, and combined vestibular plus auditory cues, respectively. A prediction of the optimal integration model is that the multisensory threshold will always be lower than either unisensory threshold.

Statistical hypothesis testing.

MATLAB 2015a and Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) were used to analyze raw data. Statistical calculations were completed following log-transformations of all threshold data, as human vestibular thresholds have been shown to follow a log-normal distribution (Benson et al. 1989; Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016). Data were transformed back to physical units for presentation, and geometric means were reported with asymmetric SE. Two-way ANOVA tests with repeated measures were performed to determine 1) the effect of frequency on vestibular, auditory, and vestibular plus auditory integration, 2) whether monaural auditory information improved perceptual thresholds when integrated with vestibular cues, and 3) whether the sensory modalities were integrated optimally. To reject the null hypothesis, α = 0.05 was used. Where a strong interaction was observed, further testing was done in low- and high-frequency ranges with Sidak’s α correction for multiple comparisons.

To characterize the nature of the observed sensory integration, four hypotheses were tested using planned comparisons to explain how vestibular and auditory thresholds combine to give vestibular-auditory thresholds, as has been done previously for visual-vestibular perceptual thresholds to roll tilt (Karmali et al. 2014): combined thresholds 1) depend only on vestibular thresholds, 2) depend only on auditory thresholds, 3) are the minimum of vestibular or auditory thresholds at each frequency, and 4) depend on the optimal predicted threshold, as defined by Eq. 1.

Weighting of information in multiple kinematic domains.

A weighted combination of cues in different kinematic domains may be used to detect motion (Karmali et al. 2014). Our sinusoidal paradigm allowed us to formally quantify this previously qualitative hypothesis. Experimentally determined perceptual thresholds were expressed in the kinematic domains of peak angular displacement (°), peak angular velocity (°/s), and peak angular acceleration (°/s2) (Fig. 3). If the brain relied exclusively on information from one of these domains, then the threshold in that domain might be expected to be frequency independent. Otherwise, a combination of multiple kinematic domains, with a frequency-independent weighting factor, could be used to make a perceptual decision.

Fig. 3.

Unisensory (vestibular, auditory; A and B, respectively) and multisensory (vestibular plus auditory; C) perceptual thresholds in 3 kinematic domains over a range of frequencies of rotation. y-axis units indicate thresholds expressed in terms of peak angular velocity thresholds (dashed lines, °/s), peak angular displacement thresholds (dotted lines, °), and peak angular acceleration thresholds (solid lines, °/s2). Weighted combinations of 2 kinematic domains in each of the test conditions gave frequency-independent (0-slope) thresholds (dash-dot lines and closed points in D–F). The 2 kinematic domains that were used in the calculation of the weighted thresholds are shown as open points and gray lines in D–F. Shading on the graphs represents the SE of the mean.

The domains lending the most weight to the frequency-independent percept are likely to be the two varying least with frequency, one increasing with frequency and the other decreasing (Karmali et al. 2014). To model the relative weighting of the two dominant domains, consider a participant whose perceptual thresholds in both kinematic domains vary with test frequency and have the property that the slope of threshold vs. frequency is between −1 and 0 for one domain and between 0 and +1 for the other domain. If T1,i and T2,i are sets of log-transformed threshold measures at i frequencies expressed in two different kinematic domains such that T1 values linearly decrease with frequency and T2 values linearly increase with frequency then a weighted combination, Tcombo,i, can be found such that Tcombo,i does not vary across the i frequencies. Tcombo,i is given by:

| (2) |

where W is a weighting factor that varies from 0 to 1 and represents the relative contribution of one kinematic domain quantified by T1 threshold values and (1 − W) the relative contribution of the other kinematic domain quantified by T2 threshold values. To calculate the value of W, recognize that Tcombo will no longer be a function of frequency when the deviation of Tcombo values from their mean value is minimal (i.e., the variance of the weighted measures is minimal). To do this analytically, define an error function, J, that calculates the squared difference between individual Tcombo,i values and the mean value of Tcombo, , given by:

| (3) |

where N is the number of threshold measures. Then substitute Eq. 2 into Eq. 3 to get the combined function:

| (4) |

where and are the mean values of the T1 and T2 threshold measures, respectively. W is found by minimizing the value of J by taking the derivative of J with respect to W setting the derivative equal to zero, and solving for W:

| (5) |

where T1,i and T2,i are the measured thresholds for the kinematic variables whose values decreased and increased, respectively, with frequency. W values were calculated for each subject for each of the vestibular, auditory, and vestibular plus binaural auditory test conditions. For the vestibular condition, T1,i were the velocity thresholds and T2,i the acceleration thresholds. For the auditory and vestibular plus binaural auditory conditions, T1,i were the displacement thresholds and T2,i the velocity thresholds.

The technique described above was verified in the following way. Simulated data sets were created consisting of thresholds derived using a specific weighting factor. The equations here were applied to the simulated data to recover the weight factor used to generate the simulated data.

RESULTS

Frequency dependence and multisensory improvement.

Unisensory perceptual thresholds for the vestibular and auditory conditions and multisensory vestibular plus binaural auditory thresholds expressed in displacement, velocity, and acceleration domains are shown in Fig. 3. Velocity-domain perceptual thresholds are shown relative to each other in Fig. 4A. Vestibular-only perceptual velocity thresholds were largest at low frequencies, decreasing (improving) monotonically over the 0.1- to 1.0-Hz frequency range from an average of 2.00°/s +0.19/−0.18 SE to 0.75°/s +0.12/−0.11. Auditory-only thresholds were smallest at low frequencies, increasing (worsening) monotonically from an average of 0.54°/s +0.07/−0.07 to 2.42°/s +0.23/−0.22. Peak velocity thresholds in the combined vestibular + auditory condition increased (worsened) monotonically with increasing frequency from an average of 0.39°/s +0.10/−0.08 to 0.95°/s +0.14/−0.13. Standard deviations can be found in the table (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Perceptual thresholds (expressed as velocity) to yaw rotations (vestibular cues only, red squares; auditory cues only, blue circles; and vestibular plus auditory cues, purple diamonds) (A). Multisensory thresholds as experimentally measured (purple diamonds), as estimated according to a best unisensory paradigm (blue circles and red squares), and as estimated according to Bayesian optimal prediction (green x) (B) are shown. Shading represents the SE of the mean.

Table 1.

Perceptual thresholds according to experimental condition

| Auditory Only |

Vestibular Only |

Vestibular + Auditory |

Vestibular + Monaural (Unilateral) Auditory |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Geometric mean | SE (lower, upper bound) | SD (lower, upper bound) | Geometric mean | SE (lower, upper bound) | SD (lower, upper bound) | Geometric mean | SE (lower, upper bound) | SD (lower, upper bound) | Geometric mean | SE (lower, upper bound) | SD (lower, upper bound) |

| Thresholds expressed as displacement, ° | ||||||||||||

| 0.1 | 2.68 | (2.35–3.05) | (1.90–3.78) | 9.99 | (9.10–10.97) | (7.81–12.79) | 1.95 | (1.55–2.46) | (1.06–3.61) | 5.34 | (3.59–7.93) | (1.87–15.21) |

| 0.2 | 2.40 | (2.07–2.78) | (1.63–3.54) | 3.53 | (3.18–3.93) | (2.67–4.68) | 1.14 | (0.88–1.47) | (0.58–2.23) | 2.61 | (2.14–3.20) | (1.53–4.45) |

| 0.5 | 1.28 | (1.14–1.43) | (0.95–1.73) | 1.00 | (0.87–1.14) | (0.70–1.43) | 0.94 | (0.83–1.06) | (0.68–1.30) | 0.96 | (0.82–1.11) | (0.64–1.42) |

| 1.0 | 1.21 | (1.10–1.33) | (0.95–1.54) | 0.38 | (0.33–0.44) | (0.26–0.56) | 0.48 | (0.41–0.55) | (0.33–1.69) | 0.47 | (0.41–0.53) | (0.34–0.65) |

| Thresholds expressed as velocity, °/s | ||||||||||||

| 0.1 | 0.54 | (0.47–0.61) | (0.38–0.76) | 2.00 | (1.82–2.19) | (1.56–2.56) | 0.39 | (0.31–0.49) | (0.21–0.72) | 1.07 | (0.72–1.59) | (0.37–3.04) |

| 0.2 | 0.96 | (0.83–1.11) | (0.65–1.41) | 1.41 | (1.27–1.57) | (1.07–1.87) | 0.45 | (0.35–0.59) | (0.23–0.89) | 1.05 | (0.85–1.28) | (0.61–1.78) |

| 0.5 | 1.28 | (1.14–1.43) | (0.95–1.73) | 1.00 | (0.87–1.14) | (0.70–1.43) | 0.94 | (0.83–1.06) | (0.68–1.30) | 0.96 | (0.82–1.11) | (0.64–1.42) |

| 1.0 | 2.42 | (2.20–2.65) | (1.89–3.09) | 0.75 | (0.64–0.87) | (0.50–1.12) | 0.95 | (0.82–1.09) | (0.65–1.37) | 0.93 | (0.83–1.06) | (0.68–1.29) |

| Thresholds expressed as acceleration, °/s2 | ||||||||||||

| 0.1 | 0.17 | (0.15–0.19) | (0.12–0.24) | 0.63 | (0.57–0.69) | (0.49–0.80) | 0.12 | (0.10–0.15) | (0.06–0.23) | 0.34 | (0.23–0.50) | (0.12–0.96) |

| 0.2 | 0.60 | (0.52–0.70) | (0.41–0.89) | 0.89 | (0.80–0.99) | (0.67–1.17) | 0.29 | (0.22–0.37) | (0.15–0.56) | 0.66 | (0.54–0.80) | (0.39–1.12) |

| 0.5 | 2.01 | (1.80–2.25) | (1.49–2.71) | 1.57 | (1.37–1.79) | (1.10–2.24) | 1.48 | (1.31–1.67) | (1.07–2.04) | 1.50 | (1.29–1.75) | (1.01–2.24) |

| 1.0 | 7.59 | (6.92–8.33) | (5.94–9.70) | 2.36 | (2.02–2.79) | (1.58–3.53) | 2.98 | (2.59–3.42) | (2.05–4.31) | 2.93 | (2.60–3.32) | (2.12–4.06) |

Differences between vestibular and auditory perceptual thresholds.

When comparing auditory- and vestibular-only perceptual velocity thresholds across the entire frequency range, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a strong interaction accounting for 66.93% of the total variation [F(3,48) = 36.07, P < 0.001)]. This strong interaction is consistent with the inverse frequency-dependent relationship of the vestibular and auditory velocity thresholds, with vestibular velocity thresholds decreasing and auditory velocity thresholds increasing with frequency. The combined vestibular and auditory thresholds show no effect of frequency [F(3,48) = 1.606, P = 0.2002] because the inverse relationship across frequency effectively canceled any overall frequency dependency. Across all frequencies, no effect of the sensory condition [F(1,48) = 0.6413, P = 0.4272] was apparent with the mean across-frequency vestibular and auditory thresholds having similar values (1.31 °/s + 0.12/−0.11 SE for vestibular thresholds and 1.31°/s + 0.13/−0.12 SE for auditory thresholds). However, there was a significant effect of sensory condition when evaluating low frequencies (0.1–0.2 Hz) in isolation [F(1,24) = 49.42, P < 0.0001] and high frequencies (0.5–1.0 Hz) in isolation [F(1,24) = 32.12, P < 0.0001].

Vestibular plus auditory integration.

Differences were seen between combined vestibular plus auditory thresholds and the unisensory thresholds of each modality {auditory: [F(1,48) = 25.25, P < 0.0001], vestibular: [F(1,48) = 31.45, P < 0.0001]} (Fig. 4B). The combined thresholds were statistically indistinguishable from either the predicted optimal integration thresholds [F(1,48) = 0.4828, P = 0.4905] or the minimum unisensory (defined as the minimum of either auditory only or vestibular only at each frequency, or “winner-take-all” strategy) thresholds [F(1,48) = 3.286, P = 0.0761]. On the basis of the differences we had observed between low- and high-frequency responses in unisensory responses, we divided the analysis of multisensory thresholds into low- (0.1–0.2 Hz) and high-frequency (0.5–1.0 Hz) responses. We found that that vestibular plus auditory responses at low frequencies differed from the best unisensory (in this case auditory-only) condition [F(1,24) = 7.177, P = 0.013] and from optimal predictions [F(1,24) = 4.481, P = 0.045] but at high frequencies were neither better than vestibular-only “winner-take-all” unisensory responses [F(1,24) = 0.392, P = 0.537] nor better than optimal predictions [F(1,24) = 3.960, P = 0.058]. Given correction for multiple comparisons, statistical significance could not be demonstrated at individual frequencies.

Weighting of stimulus cues in multiple kinematic domains.

We calculated weighting factors to quantify the relative contribution to perceptual thresholds supplied by position, velocity, or acceleration cues for each stimulus modality under the assumption that the combined threshold remained constant across frequencies (Eq. 2). Vestibular thresholds (Fig. 3) were determined to rely on a mixture of information in the velocity and acceleration domains (mean WVest,Vel = 0.58 +0.06/−0.06 SE; mean WVest,Accel = (1 – WVest,Vel) = 0.42 +0.06/−0.06). Across all frequencies, the weighted vestibular threshold value was 1.22 +0.12/−0.11. Auditory thresholds were determined to rely on a mixture of cues from the displacement (mean WAud,Disp = 0.61 +0.03/−0.03) and velocity domains [mean WAud,Vel = (1 – WAud,Disp) = 0.39 +0.03/−0.03]. Across all frequencies, the weighted auditory threshold value was 1.51 +0.15/−0.14. For the combined vestibular plus binaural auditory condition, the thresholds were determined to rely on a mixture of cues from the displacement (mean WVest+Aud,Disp = 0.44 +0.10/−0.10) and velocity domains [mean WVest+Aud,Vel = (1 – WVest+Aud,Disp) = 0.56 +0.10/−0.10]. Across all frequencies, the weighted vestibular plus binaural auditory threshold value was 0.82 +0.08/−0.07.

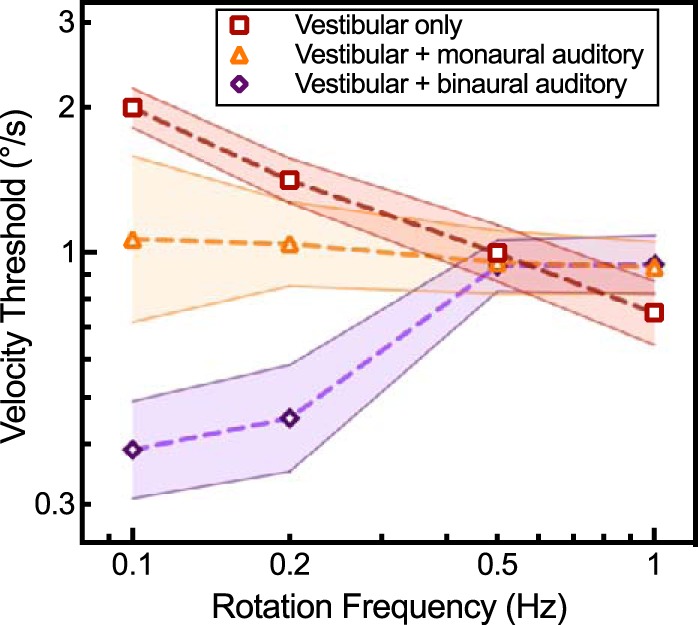

Monaural auditory contributions.

The vestibular plus monaural auditory perceptual velocity thresholds resembled vestibular-only thresholds, decreasing (improved) monotonically from an average of 1.07°/s +0.52/−0.35 SE at 0.1 Hz to 0.93°/s +0.13/−0.10 at 1.0 Hz (Fig. 5). Vestibular plus binaural auditory velocity thresholds increased with frequency. The vestibular plus monaural auditory condition, when considering all frequencies, was significantly worse than the vestibular plus binaural auditory condition [F(1,48) = 8.771, P = 0.0047]. However, after we divided the data into low- and high-frequency bands, there was a significant difference over 0.1–0.2 Hz [F(1,24) = 10.708, P = 0.0032] and not 0.5–1.0 Hz [F(1,24) = 0.001, P = 0.9927].

Fig. 5.

Perceptual thresholds to motion for 3 sensory conditions are shown: vestibular cues alone (red squares: vestibular plus head fixed audition without spatial auditory cues), vestibular plus binaural auditory cues (purple diamonds), and vestibular plus monaural auditory cues (orange triangles). Shading on the graph represents the SE of the mean.

The vestibular plus monaural (left-sided ear plug and ear muff) auditory condition did not differ significantly from the vestibular unisensory condition when considered across all frequencies [ANOVA F(1,48) = 1.914, P = 0.1729]. Inspection of the data showed marginal improvement of the vestibular plus monaural auditory condition over the vestibular-only condition from 0.1–0.2 Hz but did not reach statistical significance [F(1,24) = 4.016, P = 0.057]. At higher frequencies from 0.5 to 1.0 Hz, the vestibular plus monaural auditory condition did not differ from the vestibular-only condition [F(1,24) = 0.3820, P = 0.5424].

DISCUSSION

Overview.

Our results demonstrate that external auditory input adds meaningful information to vestibular self-motion cues in a frequency-dependent manner. They define for the first time the frequency range of motion over which the presence of combined vestibular plus auditory cues facilitates motion detection and show that the brain is able to integrate the two information streams to give an improved estimate of whole body motion perception. They also calculate the relative contribution of position, velocity, and acceleration cues for detecting movement of a sound source relative to the observer. These data provide a rigorous foundation for understanding the effect of auditory information on balance and substantiate the potential contribution of auditory cues to postural stability and gait.

Unisensory vestibular sensitivity.

We found that perceptual thresholds (expressed in terms of peak velocity) to rotational vestibular, auditory, and combined vestibular plus auditory stimuli in the azimuthal plane were frequency dependent over the range 0.1–1.0 Hz (Fig. 3). The vestibular velocity thresholds decreased (improved) from 0.1 Hz to 1.0 Hz, similar to previously reported results among subjects with normal vestibular function (Benson et al. 1989; Grabherr et al. 2008; Roditi and Crane 2012; Shayman et al. 2018b). We chose this range because it had previously been shown to encompass a transition point between a region of poor vestibular thresholds at low frequencies and better thresholds at higher rotational frequencies of vestibular stimulation and because it comprised a range of frequencies typical of normal head motion. The good vestibular thresholds at higher frequencies support the function of the vestibular system as a high-frequency sensor responsible for stabilizing the eyes during rapid head movements (Carriot et al. 2014; Mergner et al. 1991).

When vestibular thresholds were expressed as a function of peak angular acceleration, they increased with increasing frequency while vestibular velocity thresholds decreased. Consistent with the suggestion of Karmali et al. (2014), we found that frequency-independent vestibular thresholds could be derived from a weighted combination of velocity and acceleration motion cues (Fig. 3D). This frequency independence supports a hypothesis that vestibular motion detection depends on both velocity and acceleration cues as represented by a kinematic weighting model (Eq. 2). The dynamic properties of primary semicircular canal afferents could provide a physiological basis that accounts for vestibular thresholds that depend on both velocity and acceleration. Although the classic torsion-pendulum model of canal function predicts that motion information encoded by canal afferents should be primarily velocity related over the range of frequencies investigated in our study, measurements of afferent responses to rotation show a wide range of dynamics with irregular firing afferents, showing response characteristics between those expected with pure velocity or pure acceleration encoding (e.g., phase leads and gain enhancement relative to those expected from the torsion-pendulum model) (Haque et al. 2004; Tomko et al. 1981). It may be possible to devise future experiments that could test the kinematic weighting model. For example, in addition to sinusoidal stimuli, other motion profiles could be used that have a different relationship between peak velocity and peak acceleration compared with sinusoidal motion profiles. The kinematic weighting model would be supported if the weighting factor derived from sinusoidal tests also applied to results from stimuli with different motion profiles.

Unisensory auditory sensitivity.

Our data indicate that auditory velocity thresholds are lower (better) than vestibular velocity thresholds at lower frequencies but worse at higher frequencies (Fig. 4A). This may be one explanation why auditory input seems to provide dramatic improvement in navigation tasks, such as the Fukuda stepping test (Karim et al. 2018; Munnings et al. 2015; Zhong and Yost 2013), but typically less so when measuring postural sway (McDaniel et al. 2018). The former involves slow turns of the body over tens of seconds (low frequency content), whereas the latter includes higher-frequency content, including components above 0.3 Hz (Mancini et al. 2012). Given that auditory thresholds are lower than vestibular thresholds up to ~0.3 Hz, this frequency may be a reasonable upper limit of head movements for which external auditory stimuli could reasonably contribute to balance stabilization. Similarly, auditory cues would be very unlikely to contribute meaningfully to stabilization of gaze, which often requires compensation for rapid, high-frequency head movements (Grossman et al. 1988).

Multisensory integration.

We found that the brain relies on a combination of auditory and vestibular information for motion perception at low frequencies. Sensory cue combinations are often optimally integrated so that an organism places proportionally more weight on modalities that are relatively more reliable (Ernst and Banks 2002; Faisal et al. 2008). However, in some cases, a “winner-take-all” model dominates, and the best sensory stream is used in the formation of a percept while less precise information is discarded (Rahnev and Denison 2018). Our present data shown in Fig. 4B do not allow us to distinguish between these two models, but further studies involving more subjects and alternative psychophysical techniques might be able to do so. Several studies have shown optimal integration in visual plus vestibular stimulus pairs (Fetsch et al. 2010; Gu et al. 2008; Kaliuzhna et al. 2015, 2018; Karmali et al. 2014). If a similar effect is to be found here, the principle of inverse effectiveness would suggest that vestibular plus auditory cue combination would be most significant between 0.2 and 0.5 Hz, where the cues have equal and relatively poor precision (Stein et al. 2009).

We found that, in our combination experiments, responses are combinatorial at low frequencies but largely dependent on the best unisensory condition at higher frequencies. The reason for this is not clear. One possible explanation involves possible combinations of visual cues with the auditory and vestibular inputs studied here. Vision might take over from audition, rather than combine with it, at the high end of our tested frequency range (0.5 and 1.0 Hz) and then become relatively ignored at even higher frequencies (Paige 1983). If this is the case, then optimal integration of auditory and vestibular inputs might not be expected. An alternative explanation relies on the observation that prior experience is known to be related to appropriate combinatorial weighting (Rahnev and Denison 2018). Our participants in this experiment were not experienced at our specific vestibular plus auditory cue combination stimulus pair, an effect that might have differentially impacted cue combination across our range of frequencies.

We found that thresholds in the vestibular plus auditory condition at 0.2 Hz were better than expected according to a Bayesian optimal integration model. This is an unexpected and puzzling finding because thresholds should not be better than specified by “optimal integration” and requires further study to understand. The best explanation is that extra information was available in the combined condition that was not used when measuring unisensory thresholds. A similar finding has been reported before in the central auditory system, where it was explained by proposing the presence of a previously unrecognized neural encoding mechanism (Lau et al. 2017). A second possible explanation is that, in the unisensory condition, participants used different psychophysical decision making or attentional strategies in each condition, allowing more information from each sensory input to be used in the combined condition than when each was used in the more impoverished unisensory condition (Lim et al. 2017). Finally, despite efforts to keep the environment consistent in each stimulus condition, there may have been subtle variations in external stimuli that offered unintentional supplementary cues in the multisensory condition.

Implications for sensing movement of a sound source.

Although determining the location of a sound source is well understood, detecting movement of a sound source is not (Carlile and Leung 2016; Middlebrooks and Green 1991). Historically, this ability has been characterized as the “minimal audible movement angle” (MAMA), or the angular displacement necessary for motion of a sound source to be detected (Harris and Sergeant 1971). This draws on the intuitive and widely cited “snapshot theory,” which holds that perception of auditory motion depends on sequential estimates of the location of a sound rather than measuring its continuous motion profile (Carlile and Leung 2016; Grantham 1997; Perrott and Marlborough 1989). In this regard, the auditory system would be different from the visual system, which has well-defined velocity-sensitive elements (Derrington et al. 2004).

Previous work has suggested that, if displacement were the primary variable for motion detection, then we would expect displacement thresholds to be constant across all the frequencies tested (Karmali et al. 2014). We found, however, that displacement thresholds decreased at higher frequencies, indicating that angular displacement alone (MAMA) is insufficient to fully explain thresholds of auditory motion detection, just as a combination of vestibular and acceleration cues are involved in vestibular perception (Fig. 3).

We therefore examined the alternative hypothesis that other kinematic domains, such as velocity or even acceleration, might contribute to auditory motion perception. Auditory motion thresholds expressed in the displacement domain decreased slightly with frequency, and thresholds expressed in terms of velocity increased with frequency, suggesting that the brain may be using a combination of those cues to arrive at a threshold motion percept that is independent of frequency (Karmali et al. 2014). Using our model based on this hypothesis (Eq. 2), we found that an auditory threshold value weighted 61% by displacement cues and 39% by velocity cues gave a frequency-independent percept for auditory motion detection. Further kinematic derivatives, including acceleration, jerk, snap, crackle, and pop may also contribute, but the combination of two kinematic variables provided a good account of the experimental data over the range of frequencies tested. Neurophysiological studies support the concept that velocity contributes to auditory motion perception independently of location measurements. There are auditory motion-specific areas in the cortex distinct from those used to analyze static sound locations (Poirier et al. 2017), and position and velocity information are combined at the level of single neurons (Ahissar et al. 1992). This shows that the brain determines whether a sound source is moving based on neural representations of both its location and of its velocity and leads to the conclusion that the term MAMA may not reflect the true importance of velocity cues to auditory motion detection.

Integration with unilateral audition.

Unilateral listeners have difficulty localizing a static sound source in the azimuthal plane (Abel and Lam 2008). Consistent with this, our results from the vestibular plus monaural auditory condition (Fig. 5) showed that unilateral listeners received minimal benefit from an earth-stationary external sound source when sensing self-motion at high frequencies. However, our data showed some potential benefit at low frequencies, consistent with more weight being placed on peak displacement cues, which are larger at lower frequencies. The cardinal cues used for sound localization, interaural level, and interaural timing differences are not available with monaural hearing, and the brain must use other methods to determine location or movement of a sound source. One of these alternate strategies involves movement of the head to create a trigonometric baseline to estimate the location of an auditory source. Here, our participants were unable to rotate their heads volitionally during the experiment and thus could not estimate the location of the sound source in this manner (Grange et al. 2018). However, participants listening monaurally did have access to less salient auditory features, such as spectral and monaural level cues (Asp et al. 2018), which may explain the observation that there was evidence of meaningful improvement in the low end of the frequency range tested, where sound had its greatest benefit.

Implications for research and clinical testing.

Auditory contamination has long been recognized as a potential confounder in vestibular testing (Dodge 1923; Munnings et al. 2015), leading to its careful exclusion in some research studies (Roditi and Crane 2012). From the data here, we can conclude that similar care should be taken when performing clinical evaluations in environments with possible auditory interference. While our data here only apply to measuring stimuli in the yaw plane, it seems a reasonable assumption that similar effects may occur in other testing situations.

Previous epidemiological studies have shown that hearing loss is associated with falling (Lin and Ferrucci 2012), and several behavioral studies have examined the possibility that this is due to a reduction in spatial auditory cues (Agmon et al. 2017; Campos et al. 2018). Our work here contributes a rigorous description of this mechanism. However, it is important to recognize that other vestibular cues, such as pitch, roll, or linear accelerations, may contribute as much or more than yaw rotations in maintaining balance. The specifics of those interactions and how they may contribute to balance control remain to be described. It seems likely that, at the very least, thresholds to yaw rotations are important determinants of navigational accuracy. By characterizing how auditory and vestibular cues integrate, our results may help direct novel physical therapy and auditory rehabilitation techniques, including the use of hearing aids and cochlear implants to improve balance in people with hearing loss.

GRANTS

This study was supported by NIH/NIDCD grant award R01 DC017425.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., Y.O., N.-Y.N.C., and T.E.H. conceived and designed research; C.S.S. and Y.O. performed experiments; C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., Y.O., and T.E.H. analyzed data; C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., and T.E.H. interpreted results of experiments; C.S.S. prepared figures; C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., Y.O., and T.E.H. drafted manuscript; C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., Y.O., N.-Y.N.C., and T.E.H. edited and revised manuscript; C.S.S., R.J.P., F.J.G., Y.O., N.-Y.N.C., and T.E.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abel SM, Lam K. Impact of unilateral hearing loss on sound localization. Appl Acoust 69: 804–811, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2007.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agmon M, Lavie L, Doumas M. The association between hearing loss, postural control, and mobility in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Acad Audiol 28: 575–588, 2017. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar M, Ahissar E, Bergman H, Vaadia E. Encoding of sound-source location and movement: activity of single neurons and interactions between adjacent neurons in the monkey auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 67: 203–215, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp F, Jakobsson A-M, Berninger E. The effect of simulated unilateral hearing loss on horizontal sound localization accuracy and recognition of speech in spatially separate competing speech. Hear Res 357: 54–63, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AJ, Hutt EC, Brown SF. Thresholds for the perception of whole body angular movement about a vertical axis. Aviat Space Environ Med 60: 205–213, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez Rey MC, Clark TK, Wang W, Leeder T, Bian Y, Merfeld DM, Bermúdez Rey MC, Clark TK, Wang W, Leeder T, Bian Y, Merfeld DM. Vestibular perceptual thresholds increase above the age of 40. Front Neurol 7: 162, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AD, Stecker GC. Temporal weighting of interaural time and level differences in high-rate click trains. J Acoust Soc Am 128: 332–341, 2010. doi: 10.1121/1.3436540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos J, Ramkhalawansingh R, Pichora-Fuller MK. Hearing, self-motion perception, mobility, and aging. Hear Res 369: 42–55, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile S, Leung J. The perception of auditory motion. Trends Hear 20: 1–19, 2016. doi: 10.1177/2331216516644254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriot J, Jamali M, Chacron MJ, Cullen KE. Statistics of the vestibular input experienced during natural self-motion: implications for neural processing. J Neurosci 34: 8347–8357, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Santina CC, Potyagaylo V, Migliaccio AA, Minor LB, Carey JP. Orientation of human semicircular canals measured by three-dimensional multiplanar CT reconstruction. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 6: 191–206, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrington AM, Allen HA, Delicato LS. Visual mechanisms of motion analysis and motion perception. Annu Rev Psychol 55: 181–205, 2004. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge R. Thresholds of rotation. J Exp Psychol 6: 107–137, 1923. doi: 10.1037/h0076105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MO, Banks MS. Humans integrate visual and haptic information in a statistically optimal fashion. Nature 415: 429–433, 2002. doi: 10.1038/415429a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal AA, Selen LPJ, Wolpert DM. Noise in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 292–303, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nrn2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Wang S, Gu Y, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Spatial reference frames of visual, vestibular, and multimodal heading signals in the dorsal subdivision of the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci 27: 700–712, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Visual-vestibular cue integration for heading perception: applications of optimal cue integration theory. Eur J Neurosci 31: 1721–1729, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandemer L, Parseihian G, Kronland-Martinet R, Bourdin C. Spatial cues provided by sound improve postural stabilization: Evidence of a spatial auditory map? Front Neurosci 11: 357, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel D, Firzlaff U, Wiegrebe L, MacNeilage PR. Dependence of auditory spatial updating on vestibular, proprioceptive, and efference copy signals. J Neurophysiol 116: 765–775, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.00052.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel D, Schutte M, Brimijoin WO, MacNeilage PR, Wiegrebe L. Psychophysical evidence for auditory motion parallax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 4264–4269, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712058115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr L, Nicoucar K, Mast FW, Merfeld DM. Vestibular thresholds for yaw rotation about an earth-vertical axis as a function of frequency. Exp Brain Res 186: 677–681, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange JA, Culling JF, Bardsley B, Mackinney LI, Hughes SE, Backhouse SS. Turn an ear to hear: How hearing-impaired listeners can exploit head orientation to enhance their speech intelligibility in noisy social settings. Trends Hear 22: 2331216518802701, 2018. doi: 10.1177/2331216518802701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham DW. Auditory motion perception: snapshots revisited. In: Binaural and Spatial Hearing in Real and Virtual Environments, edited by Gilkey R, Anderson T. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1997, p. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman GE, Leigh RJ, Abel LA, Lanska DJ, Thurston SE. Frequency and velocity of rotational head perturbations during locomotion. Exp Brain Res 70: 470–476, 1988. doi: 10.1007/BF00247595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Angelaki DE, Deangelis GC. Neural correlates of multisensory cue integration in macaque MSTd. Nat Neurosci 11: 1201–1210, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nn.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallemans A, Mertens G, Van de Heyning P, Van Rompaey V. Playing music may improve the gait pattern in patients with bilateral caloric areflexia wearing a cochlear implant: results from a pilot study. Front Neurol 8: 404, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque A, Angelaki DE, Dickman JD. Spatial tuning and dynamics of vestibular semicircular canal afferents in rhesus monkeys. Exp Brain Res 155: 81–90, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JD, Sergeant RL. Monaural-binaural minimum audible angles for a moving sound source. J Speech Hear Res 14: 618–629, 1971. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1403.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh IJ, Watson CS. Auditory psychophysics and perception. Annu Rev Psychol 47: 461–484, 1996. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliuzhna M, Prsa M, Gale S, Lee SJ, Blanke O. Learning to integrate contradictory multisensory self-motion cue pairings. J Vis 15: 15.1, 2015. doi: 10.1167/15.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliuzhna M, Gale S, Prsa M, Maire R, Blanke O. Optimal visuo-vestibular integration for self-motion perception in patients with unilateral vestibular loss. Neuropsychologia 111: 112–116, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim AM, Rumalla K, King LA, Hullar TE. The effect of spatial auditory landmarks on ambulation. Gait Posture 60: 171–174, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Lim K, Merfeld DM. Visual and vestibular perceptual thresholds each demonstrate better precision at specific frequencies and also exhibit optimal integration. J Neurophysiol 111: 2393–2403, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00332.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Chaudhuri SE, Yi Y, Merfeld DM. Determining thresholds using adaptive procedures and psychometric fits: evaluating efficiency using theory, simulations, and human experiments. Exp Brain Res 234: 773–789, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau BK, Mehta AH, Oxenham AJ. Super-optimal perceptual integration suggests a place-based representation of pitch at high frequencies. J Neurosci 37: 9013–9021, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1507-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt H. Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics. J Acoust Soc Am 49, 2B: 467, 1971. doi: 10.1121/1.1912375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K, Karmali F, Nicoucar K, Merfeld DM. Perceptual precision of passive body tilt is consistent with statistically optimal cue integration. J Neurophysiol 117: 2037–2052, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00073.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med 172: 369–371, 2012. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Adaptive methods for estimating empirical thresholds, in Detection Theory: A User’s Guide. New York: Psychology Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Salarian A, Carlson-Kuhta P, Zampieri C, King L, Chiari L, Horak FB. ISway: a sensitive, valid and reliable measure of postural control. J Neuroeng Rehabil 9: 59, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel DM, Motts SD, Neeley RA. Effects of bilateral hearing aid use on balance in experienced adult hearing aid users. Am J Audiol 27: 121–125, 2018. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merfeld DM. Signal detection theory and vestibular thresholds: I. Basic theory and practical considerations. Exp Brain Res 210: 389–405, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2557-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T, Siebold C, Schweigart G, Becker W. Human perception of horizontal trunk and head rotation in space during vestibular and neck stimulation. Exp Brain Res 85: 389–404, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00229416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC, Green DM. Sound localization by human listeners. Annu Rev Psychol 42: 135–159, 1991. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnings A, Chisnall B, Oji S, Whittaker M, Kanegaonkar R. Environmental factors that affect the Fukuda stepping test in normal participants. J Laryngol Otol 129: 450–453, 2015. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paige GD. Vestibuloocular reflex and its interactions with visual following mechanisms in the squirrel monkey. I. Response characteristics in normal animals. J Neurophysiol 49: 134–151, 1983. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrott DR, Marlborough K. Minimum audible movement angle: marking the end points of the path traveled by a moving sound source. J Acoust Soc Am 85: 1773–1775, 1989. doi: 10.1121/1.397968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier C, Baumann S, Dheerendra P, Joly O, Hunter D, Balezeau F, Sun L, Rees A, Petkov CI, Thiele A, Griffiths TD. Auditory motion-specific mechanisms in the primate brain. PLoS Biol 15: e2001379, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnev D, Denison RN. Suboptimality in perceptual decision making. Behav Brain Sci 41: 1–107, 2018. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X18000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roditi RE, Crane BT. Directional asymmetries and age effects in human self-motion perception. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 13: 381–401, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10162-012-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayman CS, Earhart GM, Hullar TE. Improvements in gait with hearing aids and cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol 38: 484–486, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayman CS, Mancini M, Weaver TS, King LA, Hullar TE. The contribution of cochlear implants to postural stability. Laryngoscope 128: 1676–1680, 2018a. doi: 10.1002/lary.26994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayman CS, Seo J-H, Oh Y, Lewis RF, Peterka RJ, Hullar TE. Relationship between vestibular sensitivity and multisensory temporal integration. J Neurophysiol 120: 1572–1577, 2018b. doi: 10.1152/jn.00379.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BE, Stanford TR, Ramachandran R, Perrault TJ Jr, Rowland BA. Challenges in quantifying multisensory integration: alternative criteria, models, and inverse effectiveness. Exp Brain Res 198: 113–126, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1880-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MN, Barbour DL, Gronski MP, Hullar TE. Auditory contributions to maintaining balance. J Vestib Res 26: 433–438, 2016. doi: 10.3233/VES-160599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomko DL, Peterka RJ, Schor RH, O’Leary DP. Response dynamics of horizontal canal afferents in barbiturate-anesthetized cats. J Neurophysiol 45: 376–396, 1981. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Town SM, Brimijoin WO, Bizley JK. Egocentric and allocentric representations in auditory cortex. PLoS Biol 15: e2001878, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Barneveld DC, Van Opstal AJ. Eye position determines audiovestibular integration during whole-body rotation. Eur J Neurosci 31: 920–930, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigderson E, Nelken I, Yarom Y. Early multisensory integration of self and source motion in the auditory system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 8308–8313, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522615113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA, Zhong X, Najam A. Judging sound rotation when listeners and sounds rotate: Sound source localization is a multisystem process. J Acoust Soc Am 138: 3293–3310, 2015. doi: 10.1121/1.4935091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Yost WA. Relationship between postural stability and spatial hearing. J Am Acad Audiol 24: 782–788, 2013. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.24.9.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]