Although severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was identified as the causative agent of SARS [1, 2], other pathogens, including human metapneumovirus and Chlamydia pneumoniae, have been detected together with SARS-CoV in some patients [3]. Moreover, >19.6% of patients with SARS had diarrhea; however, in most cases, SARS-CoV could not be isolated from the stools of these patients [2, 3]. During the outbreak of SARS, about 60% of patients did not have definitely identified pathogens. The information to date suggests that SARS-CoV is necessary and sufficient for the causation of SARS in humans, but it remains to be determined whether microbial or other cofactors enhance the severity or transmissibility of the disease.

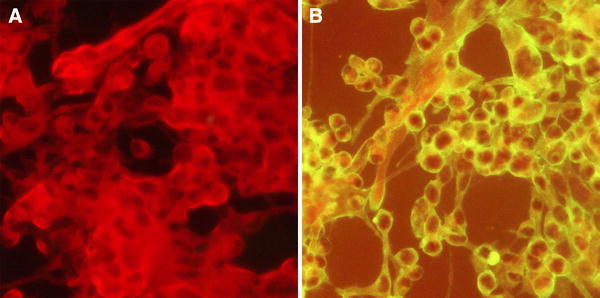

In 2003, when we examined by electron microscopy the cell culture taken from a throat swab from a 26.3-year-old woman with SARS (Case 1), we were surprised by the presence of other virus-like particles apart from SARS-CoV. These small, round particles, 20–30 nm in diameter, differed greatly from coronavirus. Viral RNA was extracted from the cell culture using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and aliquots of cDNA were amplified by Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen), with the random primers. Sequence analysis of 80 bp indicated that our isolate had high sequence identity with poliovirus Sabin 1. To confirm this result and gain more details about our isolate (named BJS01), we isolated the virus from the throat swab using human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cell line and designed primers that targeted the VP1-2A region (nt 2433–2880, forward primer 5′-TTTGTGTCAGCGTGTAATGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AATTCCATATCAAATCTAGA-3′) of Sabin PV1 strain (GenBank accession number AY184219) to perform another polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. PCR products were cloned into the pGETM vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and sequenced. Sequences were compared with those in GenBank using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), which showed 99.5% homology to Sabin 1 isolate AY184219. Neutralization assays were performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) “Manual for the virologic investigation of polio” with a set of polyclonal antiserum pools, RIVM, gifted by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [4], and the isolate BJS01 was neutralized with antiserum pools against poliovirus type 1, indicating the virus identity as poliovirus type 1. The findings from the indirect immunofluorescence assay confirmed this result (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay of the virus isolate. a Cells without virus inoculation were negative for green fluorescence. b Cells inoculated with virus BJS01 isolate showed a high intensity of green fluorescence in the cytoplasm, which suggested poliovirus type 1 replication in cultured cells

To investigate whether this poliovirus type 1 was present in other SARS patients, we collected for virus isolation and/or reverse transcription (RT)-PCR 38 specimens from 20 subjects (13 male, seven female; mean age 37.2 years; range 19–73 years), who were admitted to the Beijing 302 Hospital from March to June 2003 and who fulfilled the WHO case definition of SARS [5], and seven postmortem tissue samples from a 53-year-old man with SARS (Case 2). Stool specimens from 25 healthy individuals and 25 patients with hepatitis A or hepatitis B, and ten postmortem tissue samples from five patients with hepatitis B were available as controls (Table 1). Viral RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was carried out using primers that targeted the VP1-2A region. Nuclease-free water was used as a negative control and all of the PCR procedures were performed twice. The results showed that, including Case 1, five of 13 saliva specimens, three of eight sputum specimens, five of seven urine specimens, and all five throat swabs and six stool specimens from SARS patients were positive for OPV-like poliovirus 1. This confirmed that 15 of 21 (71.4%) SARS patients harbored OPV-like poliovirus 1 (Table 2). In contrast to the SARS specimens, only one of 50 stool specimens from control subjects, from a 5-year-old child with hepatitis A, was positive for OPV-like poliovirus 1. This finding was significantly different to that of SARS patients (p = 0.000). Interestingly, among seven postmortem tissue samples from a 53-year-old man, the kidney and small intestine but not the brain, lung, liver, spleen, or pancreas were positive for OPV-like poliovirus 1, with negative results for the postmortem kidney and small intestine tissue samples from five patients with hepatitis B.

Table 1.

Specimens collected in this study

| Subjects | Specimen | Number |

|---|---|---|

| SARS | Throat swab | 5 |

| Saliva | 13 | |

| Sputum | 8 | |

| Urine | 7 | |

| Stool | 6 | |

| Postmortem kidney | 1 | |

| Postmortem small intestine | 1 | |

| Postmortem brain | 1 | |

| Postmortem lung | 1 | |

| Postmortem liver | 1 | |

| Postmortem spleen | 1 | |

| Postmortem pancreas | 1 | |

| Controls | ||

| Healthy | Stool | 25 |

| Hepatitis | Stool | 25 |

| Postmortem kidney | 5 | |

| Postmortem small intestine | 5 | |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) specimens were collected from 21 cases; control stool specimens were collected from 25 healthy individuals and 25 patients with hepatitis A or hepatitis B. Postmortem kidney and small intestine control specimens were collected from five patients with hepatitis B

Table 2.

Detection of poliovirus strain Sabin 1 in SARS patients

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Throat swab | Saliva | Sputum | Urine | Stool | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26.3 | Female | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 2a | 53.0 | Male | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 3 | 51.4 | Female | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 4 | 27.3 | Female | ND | + | − | + | ND | + |

| 5 | 39.0 | Male | ND | ND | − | − | + | + |

| 6 | 24.3 | Male | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 7 | 30.9 | Male | ND | − | ND | ND | + | + |

| 8 | 47.9 | Male | ND | − | ND | + | + | + |

| 9 | 32.2 | Male | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | 73.3 | Male | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | + |

| 11 | 30.6 | Female | ND | ND | − | ND | ND | − |

| 12 | 46.1 | Female | + | ND | ND | − | + | + |

| 13 | 32.5 | Male | ND | − | + | + | ND | + |

| 14 | 25.8 | Male | ND | − | ND | ND | ND | − |

| 15 | 43.8 | Male | ND | − | ND | ND | ND | − |

| 16 | 31.8 | Male | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 17 | 27.3 | Male | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | + |

| 18 | 18.5 | Female | ND | ND | − | ND | ND | − |

| 19 | 42.0 | Female | ND | − | ND | ND | ND | − |

| 20 | 45.6 | Male | ND | − | ND | ND | ND | − |

| 21 | 22.0 | Female | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | + |

Throat swabs from Cases 1, 2, and 3 were used for virus isolation and then reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay; other specimens and control samples were directly subjected to RT-PCR

+ positive, − negative, ND not detected

aRT-PCR was performed directly on postmortem tissue specimens from Case 2, with positive results for the kidney and small intestine, and negative results for the brain, lung, liver, spleen, pancreas, and postmortem tissue controls

In addition, three of 15 doubly infected patients with SARS-CoV and OPV-like poliovirus died (Cases 2, 3, and 10), which gave a mortality of 20%. All six of the SARS patients without OPV-like poliovirus infection were still alive. It is worth mentioning that all three deceased subjects were older than 50 years of age, which indicates that they had never received vaccination for OPV-like poliovirus because vaccination in China was initiated in the 1960s.

Poliomyelitis has prevailed for several decades, but great progress has been made since 1988 towards its eradication. OPV is an effective vaccine against poliovirus infection, and its mutated derivatives can be detected in normal populations for weeks to months after immunization, mainly among children. Surprisingly, we detected OPV-like poliovirus 1 in many adult SARS patients. Poliovirus can be transmitted from person to person by close contact, either through upper respiratory tract secretions or the fecal–oral route [6], similarly to SARS-CoV [7], which could enable co-infection with poliovirus and SARS-CoV. The reduced immunity to poliovirus type 1 in adults [8, 9] and the impaired immunity of SARS patients also made OPV-like poliovirus 1 infection possible. In agreement with previous reports [10–12], our postmortem results showed widespread hemorrhage and necrosis in the spleen and lymph nodes and a decreased number of inherent lymphocytes (data not shown), which suggested that these SARS patients were severely immunocompromised. Moreover, lymphopenia and steroid treatment [13–15], included in this cohort (data not shown), cause deterioration of the immunological function of patients with SARS. All of these factors may facilitate the spread and replication of OPV-like poliovirus 1. However, it is still unknown whether one virus infected before the other, or if both viruses infected simultaneously.

It is highly improbable that our results were false because of the following. (1) None of the stool samples from healthy controls and only one of those from hepatitis-virus-infected controls, that from a 5-year-old child who may have been inoculated with OPV several months previously, was positive for OPV-like poliovirus 1. However, all stool samples from SARS patients were positive for OPV-like poliovirus 1 and controls were negative. (2) The laboratory used for these studies had not previously been used for poliovirus research, limiting the chances of contamination, and the virus isolation results were confirmed by another laboratory. (3) All of the PCR amplifications with positive or negative results for OPV-like poliovirus 1 were repeated with the same results. In addition, the neutralization antibody titer to the Sabin 1 BJS01 isolate from Case 3 was 2 in serum 1 versus 16 in serum 2 collected from the same patient 4 days later (data not shown), which further supported the finding of OPV-like poliovirus 1 infection in SARS patients.

The results obtained in this study indicated the existence of OPV-like poliovirus 1 in adult cases of SARS. However, the exact relationship between OPV-like poliovirus 1 and SARS/SARS-CoV was unknown and needs further research.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

H. Shen and B. Bai contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Manual for the virologic investigation of polio. WHO/EPI/GEN/97.01, p. 25–29. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1997/WHO_EPI_GEN_97.01.pdf.

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO). Case definitions for surveillance of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). http://www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefinition/en.

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Polio laboratory manual. WHO/IVB/04.10, p. 6–7. http://www.who.int/vaccines/en/poliolab/WHO-Polio-Manual-9.pdf.

- 7.Li AM, Ng PC. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in neonates and children. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F461–F465. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.075309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotto I, Handsher R, Gdalevich M, et al. Decline in immunity to polio among young adults. Vaccine. 2001;19:4162–4166. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nates SV, Martinez LC, Barril PA, et al. Long-lasting poliovirus-neutralizing antibodies among Argentinean population immunized with four or five oral polio vaccine doses 1 month to 19 years previously. Viral Immunol. 2007;20:3–10. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202:415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding Y, Wang H, Shen H, et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J Pathol. 2003;200:282–289. doi: 10.1002/path.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu J, Korteweg C. Pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1136–1147. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi KW, Chau TN, Tsang O, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiris JS, Yuen KY, Osterhaus AD, et al. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CL, Lu YT, Peng MJ, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of severe acute respiratory syndrome vis-à-vis onset of fever. Chest. 2004;126:509–517. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]