Human metapneumovirus (HMPV) is a single negative-stranded RNA-enveloped virus in the Paramyxoviridae family [1]. HMPV is known to cause respiratory tract infections. HMPV-induced encephalitis has only sporadically been documented, mostly in children [2]. In adults only three former reports exist [1, 3, 4].

An 78-year-old Caucasian male patient presented at the emergency department because of agitation and confusion. His wife reported myoclonic jerks and urinary incontinence during sleep. Glasgow coma scale was 9/15. He had not taken any psychotropic drugs. Clinical examination showed no lateralisation, plantar reflexes were in flexion. The right eye was red and slightly swollen. Cardiovascular parameters were normal. Temperature was 38.9 °C. Medical history revealed diabetes mellitus type 1, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, nicotine abuse and glaucoma.

Laboratory results showed leucocytosis of 12.600 white blood cells, a normal CRP of 1 mg/l (N < 5), slightly elevated lactate 20.3 mg/dl (N < 19.8) and glucose 161 m/dl (N < 110). Creatinine, electrolytes, enzymes, TSH and carboxy-hemoglobin were within normal limits.

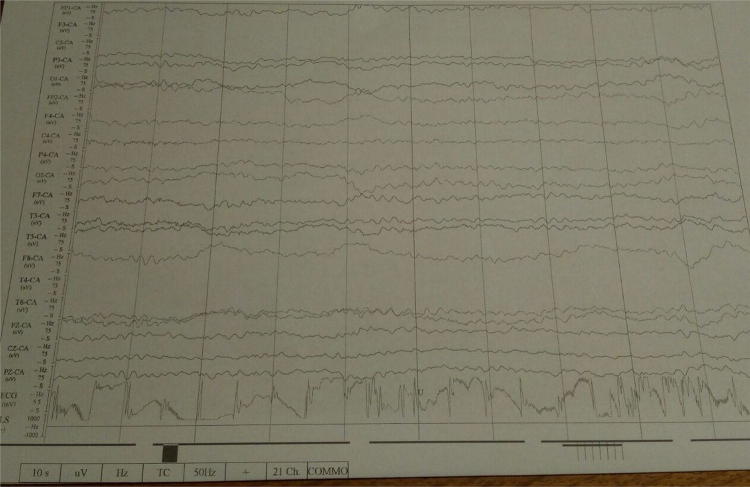

EEG showed a generalized slowing of the basal rhythm slightly more pronounced bitemporal, indicative for encephalopathy or encephalitis (Fig. 1). There were no signs of epilepsy. CT scan of the brain was normal. Chest radiography showed accentuated bronchopulmonary markings as seen in viral respiratory infections.

Fig. 1.

EEG at day 1 showing generalized slowing of the basal rhythm to 5 and 6 Hz, no focal slowing, no epileptic discharges

Because a (meningo-)encephalitis was suspected a spinal tap was performed and acyclovir, amoxicilline and ceftriaxone were initiated. CSF results, indicative for viral encephalitis, are shown in Table 1. Due to impaired consciousness and the need of vital parameter monitoring, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). During the first hours on the ICU the patient presented with two episodes of tonic-clonic seizures, successfully treated with intravenous benzodiazepines. After the second episode of seizures, levetiracetam 1 g 3 dd was added to the therapeutic regimen.

Table 1.

Overview of demographic, clinical, laboratory, EEG and MR imaging data of published adult cases of metapneumovirus-induced encephalitis

| Age/sex | Respiratory symptoms/ocular symptoms | Complaints at admission | Chest radiography | WBC in blood/differentia-tion | Serum CRP | WBC in CSF (µl) | Protein CSF (mg/dl) | EEG | MRI brain | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our case | 78/M | None/viral conjunctivitis | Agitation, confusion, seizure during sleep | Accentuated bronchopulmonary markings |

12,600 88.9% neutrophils |

1.0 mg/l N < 5) |

6 66% neutrophils |

49 | Diffuse slo-wing at day 1, normal control EEG | Normal | Remission |

| Tan and Wee [1] | 32/M | None/None | Backache and fever | Right upper and lower zone consolidation |

2700 24% neutrophils |

na | 0 | Normal | Normal | Multiple hyperintense foci | Severely disabled |

| Fok et al. [3] | 47/M | Cough, dyspnea, rhinorrhea, myalgia, headache since 2 days / none |

Unconscious GCS 10/15 |

Right basal pneumonia | Na, mild neutrophilia 8200 | 30 mg/l (N < 5) | 0 | 77 l | Normal at day 4 | Diffuse hyperintense foci | Remission |

| Jeannet et al [4] | 61/M | Influenza-like symptoms since 5 days / none | Headache and seizures | Inconclusive | Na | Na |

36 98% lympho-cytes |

139 | Na | Inconclusive | Na |

na not available

The next day the patïent was fully awake, he had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15, with a normal neurological examination.

PCR revealed to be negative for Enterovirus, Cytomegalovirus, Varicella zoster virus, Herpes simplex, Cryptococcus neoformans, Listeria monocytogenes, Haemophilus influenza, Neisseria meningitides, Str. Pneumoniae in CSF and negative for Influenza A/B, Parainfluenzavirus, Rhinovirus, Bocavirus, Adenovirus and Coronavirus in serum. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis also were excluded. Nasopharyngeal aspirate was negative for Coronavirus, but showed RNA strands of Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) with a low viral load suggestive for a recent infection.

Control EEG the same day showed a normalization of the basal rhythm to 9 Hz.

Viral conjunctivitis was confirmed by the ophthalmologist.

Cultures of blood and CSF remained sterile.

Because HMPV encephalitis was diagnosed, antibiotics were discontinued. MRI of the brain did not reveal cerebral infectious disease nor recent ischemia. Levetiracetam was discontinued after 4 months because of favourable outcome with complete remission.

In adult HMPV encephalitis cases influenza-like symptoms or respiratory infection (bronchiolitis, bronchitis or interstitial pneumonia) were reported in all, though in our and Tan’s case the patient was admitted because of other complaints, and respiratory tract infection was only revealed by chest radiography [1, 3, 4].

Neurological features of HMPV encephalitis include coma, delirious behavior, impaired consciousness, seizures, and refractory status epilepticus [2]. In the previously reported adult cases two presented with altered mental status, one with seizures. In all cases encephalitis was diagnosed on clinical grounds despite lacking laboratory support e.g. despite normal CSF analysis in Tan’s and Fok’s cases. In Jeannet’s and our case, clinical presentation, CSF pleocytosis and elevated protein levels were indicative for viral encephalitis (Table1) [1, 3, 4].

Antiviral drugs e.g. acyclovir or ribavirin were used in three patients, in two antibiotic regimen was given because of the associated interstitial pneumonia. In our patient acyclovir and antibiotics were initiated and administered until serological testing, PCR and cultures were available [1, 3, 4].

Extensive testing for viral and bacterial pathogens can help the clinician in getting a much faster diagnosis, initiating proper treatment, and predicting outcome.

Treatment for HMPV essentially remains supportive, although ribavirin was shown to be active against RSV and HMPV [1].

In Fok’s case the patient was treated with a 5 days course of methylprednisolone because of no clinical improvement was noticed and autoimmune encephalitis/cerebral vasculitis was suspected [3].

In some patients MR imaging does suggest autoimmune pathogenesis [1, 3]. In HMPV-induced encephalitis scattered cortical and subcortical T2w/FLAIR hyper intensities have been described. This is in contrast with the MR findings in Herpes encephalitis or influenza-associated encephalopathy (IAE) [5].

However, it is unclear whether direct viral cerebral invasion, or nonspecific inflammation/vasculitis, or excessive extracellular release of neurotransmitters is the responsible pathogenic factor [1, 3, 5].

In our patient MRI was within normal limits: this might be due to the uncomplicated clinical course or because of the time lapse between MRI and the clinical symptoms. In IAE rapid recovery both clinically and radiographically has been reported [5].

In patients with suspected viral encephalitis, HMPV may be considered as the causative agent, and testing for HMPV in nasopharyngeal aspirate and CSF is then required.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors report no disclosure nor conflict of interest relevant to the manuscript. All authors report no financial disclosure.

Ethical approval

This manuscript does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tan YL, Wee TC. Adult human metapneumovirus encephalitis: a case report highlighting challenges in clinical management and functional outcome. Med J Malays. 2017;72(6):372–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sánchez Fernández I, Rebollo Polo M, Muñoz-Almagro C, Monfort Carretero L, Fernández Ureña S, Rueda Muñoz A, Colomé Roura R, Pérez Dueñas B. Human metapneumovirus in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with acute encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(5):649–652. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fok A, Mateevici C, Lin B, Chandra RV, Chong VH. Encephalitis-associated human metapneumovirus pneumonia in Adult, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(11):2074–2076. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeannet N, van den Hoogen BG, Schefold JC, Suter-Riniker F, Sommerstein R. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in an adult with human metapneumovirus-associated encephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(2):370. doi: 10.3201/eid2302.161337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirat N, De Cauwer H, Ceulemans B, Vanneste D, Rossi A. Influenza-associated encephalopathy with extensive reversible restricted diffusion within the white matter. Acta Neurol Belg. 2018;118:553–555. doi: 10.1007/s13760-018-1004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]