Abstract

Background

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) is the most common personality disorder across the globe, and has been associated with heightened impulsivity and compulsivity. Examination of whether these findings extend to people with subsyndromal OCPD may shed light on pathogenic mechanisms contributing to the ultimate expression of full personality disorder.

Methods

Non-treatment seeking participants were recruited in the general community of two US cities, and completed a detailed clinical assessment, along with questionnaires and cognitive tests relating to impulsivity and compulsivity. Participants were classified into two groups: those with subsyndromal OCPD (N=104) and healthy controls free from mental disorders (N=52). Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics between the study groups were compared.

Results

Groups did not differ on age, gender, or educational levels. Subsyndromal OCPD had significantly elevated impulsivity (Barratt Impulsivity Scale) and compulsivity (Padua Inventory) scores, but did not differ on neuropsychological task performance (response inhibition, set-shifting, or decision-making). Across the whole sample in ordinary least squares modelling, self-rated OCPD scores were unrelated to Barratt Impulsivity Scale scores, but were highly related to Padua Inventory scores.

Conclusions

Subsyndromal OCD was associated with impulsivity and compulsivity on self-report questionnaires, but not cognitive tasks. Interestingly, only compulsivity scores reflected the extent of OCPD traits by self-report, suggesting impulsivity may constitute a vulnerability rather than severity marker. The extremely high rates of morbid disorders in those with subsyndromal OCPD may suggest such traits induce a propensity for other disorders.

Keywords: obsessive, anankastic, perfection, neuropsychology, cognition

Introduction

Obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is a significant public health problem estimated to affect approximately 5-8% of the US population (Grant et al., 2012). In fact, OCPD is the most prevalent personality disorder in the Western World (Volkert et al., 2018). Despite the traditional categorical focus on personality disorders as lifelong enduring conditions, it is unlikely that OCPD is present “at birth”; rather, it likely develops over time, being present along a continuum from zero symptoms, to some symptoms, to full diagnostic symptoms (i.e. diagnostic criteria met). The majority of research on clinical and cognitive associations with OCPD has understandably focused on the full disorder (Grant et al., 2012). However, many types of psychiatric pathology also can exist in a milder (i.e. subsyndromal) form in the background population, and scrutiny of such milder forms can shed light on the chain of pathogenesis from “health” to “disease” (Chamberlain et al., 2005). Two concepts relevant to this progression are impulsivity (tendency towards inappropriate premature actions) and compulsivity (tendency towards repetitive habits) (Evenden, 1999; van den Heuvel et al., 2016). OCPD could be seen as the ‘ultimate’ compulsive disorder, due to the typical rigid response style, and conservative values often observed, which can be seen as risk averse (American Psychiatric Association, , 2013).

On the other hand, recent data suggest that the expression of impulsive and compulsive symptoms may both be driven by a common latent factor termed ‘disinhibition’ (Chamberlain et al., 2019; Tiego et al., 2018), and so OCPD may be expected to be somewhat impulsive. The evidence for impulsivity in OCPD is less robust perhaps than that for compulsivity but may merit further examination. In an early study, comprising a mix of individuals who were self-referred due to aggression problems (n=29), or who had been clinically-referred due to aggression problems (n=89), OCPD was evident in 24% of the sample (Villemarette-Pittman, et al., 2004). The authors argued for a compensatory theory for the development of OCPD, at least in some cases, specifically that some individuals with disinhibition may adopt a structured personality style (OCPD, or features thereof), in order to sustain functioning in academic and social spheres. Although perhaps not uniformly distributed across everyone with OCPD, there might be some elements of impulsivity as has been reported in subgroups of people with OCD (Prochazkova et al., 2018). In addition, the National Epidemiological Study of Addictions and Related Conditions (NESARC) found significant associations between OCPD and a range of addictive and impulsive disorders (e.g., substance use disorders, ADHD) (Grant et al., 2012). Interestingly, when compared to healthy controls, participants with OCPD have reported significantly higher levels of negative affectivity, trait anger, emotional intensity, and emotion regulation difficulties strategies), all which often underlie impulsivity (Steenkamp et al., 2015). Taken together, these data are suggestive of some impulsive elements in at least some individuals with OCPD, and as such this topic may merit further examination.

Because OCPD can be conceptualized from neurocognitive and psychological perspectives in terms of excessive top-down control over behavior, leading to rigid approaches to life, difficulty adapting to change, and reluctance to delegate, some research has examined compulsivity in OCPD, while there has been less focus on impulsivity to date. Data studies indicate that people with OCPD experience impairments across a spread of cognitive domains including working memory, decision-making, and cognitive flexibility (Paast et al., 2016; Whitton et al., 2014). In a recent study of 21 adults with OCPD compared to controls, the analysis of set-shifting ability on the Intra-Extra Dimensional [IED] task (a computerized task) showed that OCPD participants were significantly impaired on measures related specifically to the extra-dimensional shift, which reflects the ability to inhibit and shift attention away from one stimulus dimension to another (Fineberg et al., 2015). OCD patients (as well as other typically compulsive disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder and anorexia nervosa) have also demonstrated deficits in this domain in previous research, specifically the extra-dimensional shift in a group with OCD comorbid with OCPD; and in OCD alone (Fineberg et al., 2007; Chamberlain et al., 2007; Chamberlain et al., 2006). In a study comparing 25 people with OCPD to 25 controls, OCPD was associated with perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, and impaired executive planning on the Tower of London task (Paast et al., 2016). Thus, evidence from several studies yield deficits in OCD, particularly on cognitive flexibility paradigms (set-shift and card sort tasks) relevant to compulsivity (Kehagia et al., 2010). Executive dysfunction including set-shifting deficits have also been reported in a sample of undergraduate psychology students as a function of self-report OCPD scores (Garcia-Villamisar and Dattilo, 2015).

The aim of this study was to compare subsyndromal OCPD cases to healthy controls on cognitive as well as questionnaire measures of impulsivity and compulsivity. We ruled out clinical cases of OCPD based on gold-standard clinical interview. We hypothesized that subsyndromal OCPD would be associated with elevated impulsivity and compulsivity compared to healthy controls, in keeping with both of these concepts being of relevance in the chain of pathogenesis from ‘normal’ personality to pathologic OCPD.

Material and Methods

Participants

Non-treatment seeking individuals were recruited using media advertisements in the general community of two US cities. All participants were aged 20-29 (to help ensure a homogenous sample and that groups would be matched for age), and had gambled at least five times in the past year (since this was part of a wider study examining impulsive behaviors). Study exclusion criteria were (1) inability to understand and provide consent; and (2) presence of a formal personality disorder identified through screening (see below); and (3) presence of mental disorder in the control group. Each participant received a $50 gift card to an online store as compensation. Participants meeting inclusion criteria were grouped as “subsyndromal OCPD” (endorsing one or more OCPD criteria by structured clinical interview but falling short of the number of symptoms necessary for the formal diagnosis); and “healthy controls”, who had no symptoms of OCPD, nor other mental disorders (including no current impulse control disorder or known personality disorder).

The study procedures followed the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki. The University of Minnesota and University of Chicago Institutional Review Boards approved the study procedures and consent process. All subjects provided written, voluntary informed consent after study procedures were explained.

Assessments

Demographic variables, including age, gender, and highest level of education completed, were recorded for all participants. Subjects received a psychiatric evaluation using: the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (First et al., 1997); Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998); and the Minnesota Impulse Disorders Inventory (MIDI) (Grant et al., 2005; Chamberlain and Grant, 2018). The SCID identified personality disorders (including OCPD symptoms), the MINI identified mainstream current psychiatric disorders (e.g. mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders), and the MIDI identified current impulse control disorders. Additionally, participants completed an instrument assessing presence of each of the OCPD diagnostic criteria. For each criterion, a question asked the participant if the description applied to them, on a scale of “no” (0), sometimes (1), or often (2).

Participants also completed self-report questionnaires and computerized cognitive tasks focusing on impulsivity and compulsivity. Questionnaires comprised: The Barratt Impulsivity Scale-11 (BIS), a 30-item self-report of three domains of impulsivity (Patton et al., 1995; Reise et al., 2013; Stanford et al., 2016); and the Padua Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (Washington Revision), a 39-item questionnaire designed to measure O-C symptoms dimensionally (Burns, 1995; Burns et al., 1996).

Cognitive tasks were completed in a quiet room using a touch-screen computer, supervised by a trained assessor, and included:

Intra-Extra Dimensional Set Shift Task (IED) (Owen et al., 1991): This task examines cognitive flexibility. Subjects are presented with four boxes: two contain pink shapes and two are blank. Using a rule set by the computer, subjects are notified that one of the displayed shapes is correct and the other is incorrect. Individuals must learn this rule and then select the correct shape in as many trials as possible. Once the subject chooses a number of correct shapes the computer switches the rule to introduce a new “correct” shape. The subject must adapt; this is the intra-dimensional set shift. Following this portion of the task the computer introduces a set of white shapes overlaying the pink shapes. The new correct shape is one of the white shapes. Again, the subject must identify the correct shape as chosen by the computer. This addition of stimuli is the extra-dimensional set shift (ED). The number of total errors throughout the task and the number of errors specifically pertaining to the extra-dimensional set shift were the measures of interest.

Stop Signal Response Task (SSRT) (Logan et al., 1984; Aron et al., 2004): This task measures response inhibition. Subjects are presented with a series of directional arrows that appear one at a time on the screen. The subject must immediately press the corresponding arrow computer key matching the direction of the arrow as fast as they are able. When a buzzer sounds after the directional arrow is displayed the subject must resist pressing the computer key. The estimated time it takes for the subject to suppress the already triggered response when the buzzer sounds is calculated as the ‘stop signal reaction time’, which was our measure of interest.

Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT) (Rogers et al., 2003; Rogers et al., 1999): The CGT examines decision-making. During each trial subjects are presented with ten blocks, a portion of which are red and a portion of which are blue. A token randomly resides under one of these ten boxes. Subjects must decide if they think the token resides under a red or blue box. After a decision is made they are given an opportunity to bet a certain amount by pressing a box showing decreasing values on the screen. After a time, the box shows increasing values and the subject must again decide how much they want to bet. Subjects were motivated to earn points on the task as their reward – we did not offer financial incentives for completing the task or performing well. Measures of interest were risk adjustment, quality of decision-making, and the overall proportion of points gambled

Data Analysis

Primary Analysis: Differences between the two study groups were identified using independent sample t-tests for continuous measures, and likelihood ratio Chi-square tests for categorical measures. Secondary Analysis: In order to evaluate possible relationships between OCPD tendencies and variables identified in the Primary Analysis, we fitted an ordinary least squares model with the Y (i.e. model) variable being OCPD scores (from the self-report scale described in the methods) and X variables (i.e. model effects) being those identified in the Primary Analysis.

Missing data were not imputed. P values were shown uncorrected but were only considered significant at p<0.05 Bonferroni corrected (Primary Analysis) and False Discovery Rate corrected (FDR) (Secondary analysis). All analyses were conducted using JMP Pro.

Results

The sample size was N=104 people with subsyndromal OCPD and n=52 healthy controls. The two study groups did not differ from each other in terms of age, gender distribution, or educational levels (Table 1). Most people in the subsyndromal OCPD group endorsed one OCPD criterion (53 [51%]), with some endorsing two criteria (36 [34.6%]), and some three criteria [15 [14.4%]).

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants with Subsysndromal OCPD Compared to Controls.

| Subsyndromal OCPD (N=104) | Healthy Controls (N=52) | t | Uncorrected p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 24.8 (2.4) | 24.4 (2.4) | 1.088 | 0.279 |

| Gender, Female, N[%] | 43 [41.4%] | 27 [51.9%] | 1.564 LR | 0.211 |

| Education score | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.0) | -0.611 | 0.543 |

| Barratt Impulsivity Questionnaire, total | 67.6 (13.1) | 62.0 (10.3) | 2.875 | 0.005 * |

| Padua Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory, total | 24.8 (22.8) | 15.2 (17.4) | 2.859 | 0.005 * |

| IED ED errors | 11.7 (10.5) | 10.0 (9.4) | 1.042 | 0.299 |

| SST SSRT, msec | 185.1 (73.6) | 176.9 (52.3) | 0.805 | 0.422 |

| CGT Proportion bet | 0.56 (0.14) | 0.54 (0.13) | 0.884 | 0.379 |

| CGT Quality of Decisions | 0.93 (0.09) | 0.95 (0.09) | -0.942 | 0.349 |

| CGT Risk Adjustment | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.1) | -0.100 | 0.320 |

LR: Likelihood Ratio chi-square test, df=2.

Significant a p<0.05 Bonferroni corrected.

IED = Intra-Dimensional/Extra-Dimensional shift task; ED = extra-dimensional shift; SST =Stop Signal Task; SSRT; Stop Signal Reaction Time; CGT = Cambridge Gamble Task.

In the subsyndromal OCPD group, 45.6% of cases had one or more current mental disorders as assessed using the MINI, and 40.4% of cases had one or more current impulse control disorder on the MIDI. The following impulse control disorders were observed in N [%] of cases in the subsyndromal OCPD group: compulsive buying disorder (8 [7.8%]), intermittent explosive disorder (7 [7.1%]), pyromania (1 [0.1%]), gambling disorder (33 [32.4%]), compulsive sex disorder (6 [5.9%]), and binge-eating disorder (4 [3.9%]). The N [%] of subjects in the subsyndromal OCPD group with a given number of impulse control disorders were: one disorder 28 [28.3%], two disorders 8 [8.1%], three disorders 3 [3.0%], four disorders 1 [1%]. The following mainstream mental disorders were observed in N [%] of cases in the subsyndromal OCPD group: major depressive disorder (6 [5.9%]), panic disorder (1 [1.0%]), agoraphobia (10 [9.7%]), social phobia (4 [3.9%]), OCD (5 [4.9%]), post-traumatic stress disorder (4 [3.9%]), alcohol use disorder (22 [21.4%]), substance use disorder (17 [16.5%]), psychotic spectrum (2 [1.9%]), bulimia nervosa (3 [2.9%]), and generalized anxiety disorder (3 [2.9%]).

Summary of demographic, clinical, and cognitive data for the two groups is shown in Table 1. For the impulsivity and compulsivity questionnaires, the subsyndromal OCPD group had significantly elevated rates of Barratt Impulsivity Scale total scores, and Padua Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory total scores, compared to the healthy controls. For the cognitive tests relating to impulsivity and compulsivity, no significant group differences were observed.

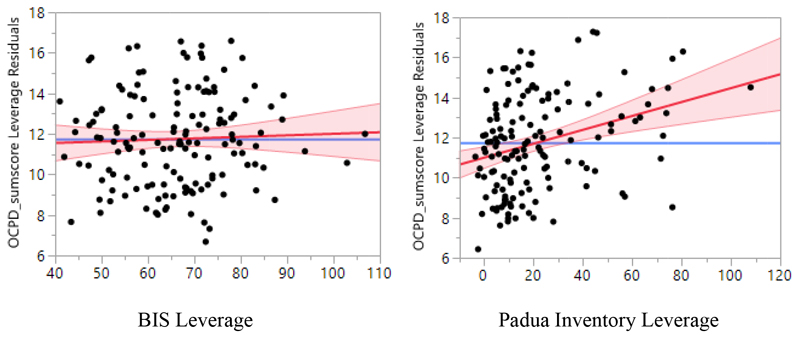

In secondary analysis, ordinary least squares indicated that self-rated OCPD scores were significantly related to Padua Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory scores (FDR LogWorth 3.237, FDR p=0.0006), marginally to age (FDR LogWorth 1.453, p=0.0353), but not Barratt Impulsivity Scale scores (FDR LogWorth 0.201, p=0.630). The overall model had R square = 0.13, and p<0.0001. The raw correlations between self-rated OCPD scores and the other variables of interest were as follows: Padua Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory scores (r=0.30, p=0.003), Barratt Impulsivity Scale scores (r=-0.07, p=0.457).

Discussion

Our results suggest that subsyndromal OCPD, like full OCPD, is associated with heightened impulsivity and compulsivity compared to healthy controls. Contrary to expectation we did not detect similar group differences on the neurocognitive tests that were deployed. This may suggest that questionnaire-based measures may be more sensitive to the earlier stages of pathology along the chain of pathogenesis from health, to existence of OCPD traits, to full OCPD. Interestingly, in secondary analysis using least square modelling, only compulsivity (as indexed by the Padua Inventory) was significantly related to higher self-reported OCPD scores, whereas Barratt Impulsivity Scale scores were not. This was also the case when using conventional correlation analyses. One likely interpretation is that impulsivity constitutes a risk or ‘vulnerability’ marker for OCPD; as such, impulsivity is found in people with OCPD traits but does not appear related to the extent of such traits. Whereas, compulsivity may more closely relate to chronicity and severity, as suggested by our finding that the number of OCPD traits endorsed correlated with Padua Obsessive-Compulsive inventory scores. Confirmation of this interpretation would require longitudinal research over a long time frame, because it is likely that OCPD traits and disorder develop slowly over time as an individual develops. Given the cross-sectional nature of these data, temporal or causal interpretations are yet not possible.

If these subjects ultimately develop OCPD, these findings would suggest that using questionnaire-based measures of impulsivity and compusivity might lead to improved early detection of those who will develop OCPD. Given that endorsing any degree of OCPD symptoms (i.e. one or more diagnostic criteria, in people who did not meet full OCPD diagnostic criteria) was associated with significantly greater impulsivity and compulsivity, early assessment and psychological interventions (for example, cognitive therapy addressing core features of impulsivity and compulsivity) could theoretically abort the development of serious personality pathology.

This study represents the first examination of candidate antecedents in non-pathological individuals who may be at risk for the development of OCPD, i.e. in those with subsyndromal symptoms. There exist, however, several limitations. First, for convenience we focused on a relatively narrow range of measures, both in terms of questionnaires and cognitive tasks. A greater number of tasks with broader examination of cognitive domains may have detected differences between the groups. Second, we defined subsyndromal OCPD a priori by having one or more OCPD symptoms, but falling short of clinical caseness. We included those even endorsing one diagnostic criterion in this definition because we wished to maximize the sample size and thus statistical power to detect differences versus controls. Future studies could consider using other definitions, such as endorsement of at least two criteria. In this study we did not include a direct comparison group with OCPD because such a group would be unlikely to be recruited in sufficient number from a non-treatment seeking population based sample. Questions remain whether there exist significant differences in psychopathology between OCPD and those with subsyndromal OCPD symptoms. Additionally, there are no established standards for categorizing OCPD across a continuum. Additionally, the fact that all participants had gambled at least 5 times in the past year certainly skews the findings and prevents their generalization to the whole population of individuals who might have “subsyndromal OCPD.” .Finally, the cross-sectional nature of these data precludes our ability to establish temporal patterns. The question remains, therefore as to whether these cognitive findings will accurately predict the development of OCPD. Until those data are available, temporal interpretations are not possible.

Figure 1.

Leverage plots from the standard least square model. Self-rated OCPD scores did not relate significantly to Barratt Impulsivity Scale total scores (left; FDR p=0.630), but did to Padua Inventory total scores (right; FDR p=0.0006).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Disclosures

This study was funded by internal funds. Dr. Grant receives yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Norton Press, and McGraw Hill. Dr. Chamberlain consults for Cambridge Cognition, Shire, Promentis, and Ieso Digital Health. Dr. Chamberlain receives a stipend from his work as Associate Editor at Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews; and at Comprehensive Psychiatry. Chamberlain’s involvement in this study was supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship (110049/Z/15/Z).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL. Padua Inventory-Washington State University Revision. Department of Psychology, Washington State University; Pullman, WA: 1995. (Available from G. Leonard Burns, Pullman, WA 99164-4820) [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Keortge SG, Formea GM, Sternberger LG. Revision of the Padua Inventory of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms: distinctions between worry, obsessions, and compulsions. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:163–173. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Blackwell AD, Fineberg NA, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: the importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:399–419. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Blackwell AD, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Motor inhibition and cognitive flexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1282–1284. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Menzies LA, Blackwell AD, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Impaired cognitive flexibility and motor inhibition in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:335–338. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Grant JE. Minnesota Impulse Disorders Interview (MIDI): Validation of a structured diagnostic clinical interview for impulse control disorders in an enriched community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2018;265:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Tiego J, Fontenelle L, Hook R, Parkes L, Segrave R, Hauser TU, Dolan RJ, Goodyer IM, Bullmore E, Grant JE, et al. Fractionation of impulsive and compulsive trans-diagnostic phenotypes and their longitudinal associations. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 19; doi: 10.1177/0004867419844325. 2019 4867419844325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Day GA, de Koenigswarter N, Reghunandanan S, Kolli S, Jefferies-Sewell K, Hranov G, Laws KR. The neuropsychology of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: a new analysis. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:490–499. doi: 10.1017/S1092852914000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Sharma P, Sivakumaran T, Sahakian B, Chamberlain SR. Does obsessive-compulsive personality disorder belong within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum? CNS Spectr. 2007;12:467–482. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Villamisar D, Dattilo J. Executive functioning in people with obsessive-compulsive personality traits: evidence of modest impairment. J Pers Disord. 2015;29:418–430. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2013_27_101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Levine L, Kim D, Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2184–2188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Mooney ME, Kushner MG. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehagia AA, Murray GK, Robbins TW. Learning and cognitive flexibility: frontostriatal function and monoaminergic modulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: a model and a method. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1984;10:276–291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Roberts AC, Polkey CE, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalo-hippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:993–1006. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90063-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paast N, Khosravi Z, Memari AH, Shayestehfar M, Arbabi M. Comparison of cognitive flexibility and planning ability in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder, patients with obsessive compulsive personality disorder, and healthy controls. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28:28–34. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazkova L, Parkes L, Dawson A, Youssef G, Ferreira GM, Lorenzetti V, Segrave RA, Fontenelle LF, Yücel M. Unpacking the role of self-reported compulsivity and impulsivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2018;23(1):51–58. doi: 10.1017/S1092852917000244. Epub 2017 May 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Moore TM, Sabb FW, Brown AK, London ED. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11: reassessment of its structure in a community sample. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:631–642. doi: 10.1037/a0032161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RD, Everitt BJ, Baldacchino A, Blackshaw AJ, Swainson R, Wynne K, Baker NB, Hunter J, Carthy T, Booker E, London M, et al. Dissociable deficits in the decision-making cognition of chronic amphetamine abusers, opiate abusers, patients with focal damage to prefrontal cortex, and tryptophan-depleted normal volunteers: evidence for monoaminergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:322–339. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RD, Tunbridge EM, Bhagwagar Z, Drevets WC, Sahakian BJ, Carter CS. Tryptophan depletion alters the decision-making of healthy volunteers through altered processing of reward cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:153–162. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;5920(Suppl):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM. Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;47:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp MM, Suvak MK, Dickstein BD, Shea MT, Litz BT. Emotional Functioning in Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder: Comparison to Borderline Personality Disorder and Healthy Controls. J Pers Disord. 2015;29(6):794–808. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_174. Epub 2015 Jan 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiego J, Oostermeijer S, Prochazkova L, Parkes L, Dawson A, Youssef G, Oldenhof E, Carter A, Segrave RA, Fontenelle LF, Yücel M, et al. Overlapping dimensional phenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity explain co-occurrence of addictive and related behaviors. CNS Spectr. 2018:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S1092852918001244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel OA, van Wingen G, Soriano-Mas C, Alonso P, Chamberlain SR, Nakamae T, Denys D, Goudriaan AE, Veltman DJ. Brain circuitry of compulsivity. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;26:810–827. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemarette-Pittman NR, Stanford MS, Greve KW, Houston RJ, Mathias CW. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and behavioral disinhibition. The Journal of psychology. 2004;138(1):5–22. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.138.1.5-22. Epub 2004/04/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709–715. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton AE, Henry JD, Grisham JR. Moral rigidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder: do abnormalities in inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility and disgust play a role? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2014;45:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]