Abstract

Influenza virus infection (IVI) is typically subclinical or causes a self-limiting upper respiratory disease. However, in a small subset of patients IVI rapidly progresses to primary viral pneumonia (PVP) with respiratory failure; a minority of patients require intensive care unit admission. Inherited and acquired variability in host immune responses may influence susceptibility and outcome of IVI. However, the molecular basis of such human factors remains largely elusive. It has been proposed that homozygosity for IFITM3 rs12252-C is associated with a population-attributable risk of 5.4 % for severe IVI in Northern Europeans and 54.3 % for severe H1N1pdm infection in Chinese. A total of 148 patients with confirmed IVI were considered for recruitment; 118 Spanish patients (60 of them hospitalized with PVP) and 246 healthy Spanish individuals were finally included in the statistical analysis. PCR-RFLP was used with confirmation by Sanger sequencing. The allele frequency for rs12252-C was found to be 3.5 % among the general Spanish population. We found no rs12252-C homozygous individuals in our control group. The only Spanish patient homozygous for rs12252-C had a neurological disorder (a known risk factor for severe IVI) and mild influenza. Our data do not suggest a role of rs12252-C in the development of severe IVI in our population. These data may be relevant to recognize whether patients homozygous for rs12252-C are at risk of severe influenza, and hence require individualized measures in the case of IVI.

Keywords: Influenza, Oseltamivir, Influenza Virus Infection, Severe Influenza, Require Intensive Care Unit Admission

Introduction

Influenza is mainly caused by H1N1 and H3N2 influenza A virus (IAV) and influenza B virus. Most individuals, including those infected with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 IAV (H1N1pdm), experience an uncomplicated influenza. Up to 75 % of infections with seasonal influenza or H1N1pdm are estimated to be subclinical [1–4]. However a low percentage of H1N1pdm-infected patients, many of them without known risk factors, develop primary viral pneumonia (PVP) and a minority even develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) [2, 4]. Inherited variability in host immune responses may influence susceptibility and outcome of IAV infection, but the molecular nature of such factors remains largely elusive [5–8].

IFITM3 was found to restrict the entry and replication of pathogenic viruses, including IAV, in both mice and humans [9–11]. The variant IFITM3 rs12252-C alters a splice acceptor site and encodes an aberrant form of the protein lacking the N-terminal 21 amino acids (Δ21 IFITM3). Conflicting results about the impact of the IFITM3 rs12252-C variant, coding for the Δ21 IFITM3 protein, in controlling IAV restriction in vitro have been reported [9, 10]. It has been proposed that homozygosity for the rs12252-C allele is associated with development of severe influenza in Northern Europeans and severe IAV infection in Asians [9, 12, 13]. However, these results were not replicated in a recent report from the United Kingdom [14]. In the present study, we assessed whether the IFITM3 rs12252-C allele is associated with susceptibility to and severity of influenza virus infection (IVI) among a white Spanish population.

Patients and methods

Patients and controls

We performed a case-control genetic association study aimed to analyze the role of the IFITM3 rs12252 polymorphism in the susceptibility and severity of IVI. From July 2009 to March 2014, 152 patients with confirmed IVI from five tertiary Spanish Hospitals and primary care centers from Gran Canaria (Spain), were considered for recruitment. Data and samples from ambulatory patients and from 44 % of the hospitalized patients were retrospectively obtained; in the remaining patients, data were obtained prospectively. Ethnicities other than white Spanish were excluded. All patients were treated with oseltamivir, and only one patient had been previously vaccinated against H1N1pdm.

The general Spanish population group consisted of 246 (blood and bone marrow donors, as well as hospital staff) unrelated white Spanish volunteers (age 33.28 ± 16.47 years; 43.9 % females). No data about IVI were available in this group, and none of these individuals had previously developed any severe respiratory illness.

Detection of influenza virus infection

Influenza A virus H1N1pdm was detected in nasopharyngeal swabs using the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Infection by influenza viruses other than H1N1pdm was confirmed by either a fourfold increase in complement fixation titers between acute and convalescent phases (11 out of the 152 patients) or RT-PCR (N = 7).

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from 400 μl of peripheral blood using iPrep™PureLink™gDNA Blood kit in the iPrep™Purification Instrument (Invitrogen by Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Extracted DNA integrity was checked by NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). DNA samples were conserved at −40 °C.

Genotyping was performed at the Department of Immunology of the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain). Analysis of the IFITM3 rs12252 polymorphism was performed by means of PCR-RFLP. PCR was carried out with the pair of primers 5′-AATTTGTTCCGCCCTCATCT-3′ and 5′-ATGTCGTCTGGTCCCTGTTC-3′ in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9600 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Amplification was carried out with a first heating at 95 °C for 5 min in order to pre-denature the template DNA, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The final extension was completed at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were digested with one unit of BalI (Promega Co., WI, USA) for 3 h at 37 °C, and then separated on 3 % agarose gel and visualized under UV with etidium bromide. After restriction enzyme digestion, fragments, in function of the length of 342, 197 and/or 145 bp, were classified in accordance with the genotype.

In order to confirm genotypes, 10 % of the samples were sequenced (including all individuals homozygous for rs12252-C). PCR products were purified with ExoSAP-iTTM (Amersham Biosciences), according to manufacturer’s protocol. Purified PCR products were sequenced using the ABI Prism BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on the ABI Prism 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, California, USA). To ensure the removal of BigDye® Terminator v3.1 along with dNTPs, salts and other low molecular weight materials, Performa® DTR Gel Filtration Cartridges (EdgeBio, Gaithersburg, USA) were used to minimize the potential for interference with sequencing applications. Both sense and antisense strands of PCR products were directly sequenced using the same primers used for the PCR amplification.

Data analysis

The number of individuals with each genotype was calculated by direct counting. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and allele frequencies were calculated using the PLINK software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/). Statistical analysis of the data was performed with SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). χ2 test or Fisher Exact test, when needed, and odds ratio with 95 % confidence intervals were calculated. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the hospitals involved. Informed consent, provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki, was obtained from all patients and/or from their legal representatives.

Results

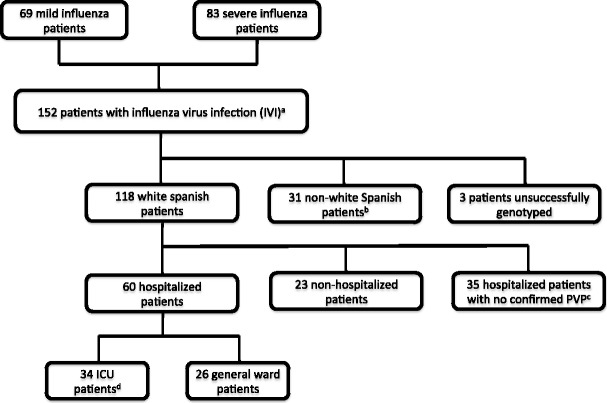

Among the 152 patients with confirmed IVI initially recruited, 31 patients were excluded from the analysis due to ethnicities other than white Spanish, and in three individuals genotyping was unsuccessful. The study group comprised 118 Spanish Caucasian patients. Sixty out (51 %) of these patients were hospitalized and had radiographic evidence of PVP; 23 were attended at primary care centers, and 35 patients were hospitalized with no evidence of PVP. Thirty-four patients required ICU admission (20 [59 %] with ARDS) (Fig. 1). Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Selection process for patients with influenza virus infection. Infection by influenza virus infection was confirmed in all the patients

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of influenza virus infected patients

| Characteristics | Patients with IVI (n = 118) |

Hospitalized patients with PVP a

(n = 60) |

Patients with ICU admission (n = 34)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 45.81 ± 18.4c | 49.18 ± 16.76c | 49.44 ± 17.57c |

| Gender (female/male) | 50 / 68 | 24 / 36 | 13 / 21 |

| Pregnancy | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No comorbidities | 46 (39.0) | 22 (36.7) | 11 (32.4) |

| Comorbidities d | 72 (61.0) | 38 (63.3) | 23 (67.6) |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 22 (18.6) | 14 (23.3) | 10 (29.4) |

| BMI ≥ 40 | 5 (4.2) | 4 (6.7) | 2 (5.9) |

| Diabetes | 24 (20.3) | 14 (23.3) | 9 (26.5) |

| Immunosupression | 17 (14.4) | 4 (6.7) | 3 (8.8) |

| COPD | 13 (11.0) | 6 (10.0) | 2 (5.9) |

| Asthma | 22 (18.6) | 8 (13.3) | 3 (8.8) |

| Neurological disease | 11 (9.3) | 7 (11.7) | 6 (17.6) |

| Heart disease | 20 (16.9) | 13 (21.7) | 7 (20.6) |

| Type of influenza virus | |||

| A pH1N1/09 | 104 (0.88) | 56 (93.3) | 33 (97.1) |

| A H3N2 | 3 (0.025) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (2.9) |

| Non-subtyped influenza A | 4 (0.034) | − | − |

| Influenza B | 2 (0.017) | 1 (1.7) | − |

| Influenza A and influenza B | 2 (0.017) | − | − |

| Influenza A and S. pneumoniae | 3 (0.025) | − | − |

IVI Influenza virus infection, PVP primary viral pneumonia, ICU intensive care unit, BMI body mass index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

aPrimary viral pneumonia confirmed by chest radiograph evidence

bFour patients died as a consequence of IVI

cData are presented as mean ± SD or number of individuals (%)

dSome patients had more than one comorbidity

The allele frequency for rs12252-C was found to be 3.5 % among the general Spanish population, a frequency similar to that reported for European populations in the 1000 Genomes project data source (www.1000genomes.org). We found no individuals homozygous for rs12252-C allele in our control group, nor on the available data from 503 individuals in the European population from the 1000 Genomes project. The IFITM3 variant rs12252 was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 0.05) in all the studied groups.

Among our 118 Spanish patients with influenza, homozygosity for rs12252-C was identified only in one patient with mild H1N1pdm infection. Nevertheless, two CC homozygous individuals with severe IVI among the 30 patients who did not satisfy the criteria of inclusion were found. Both patients were of Asian ethnicity, where the prevalence of homozygosity for the variant rs12252-C is much higher (26–44 %) [12, 13].

We performed a case/control study to compare the allele and genotype frequencies between influenza-infected patients and our control group. These comparisons did not yield significant results (Table 2). The same comparison was performed with data obtained from the IBS population (Iberian population in Spain, n = 107) in the 1000 Genomes project, and also with combined data from the control group of our study and the IBS population (n = 353). This last comparison showed a near significant association of the rs12252-C allele with susceptibility to influenza (p = 0.048; OR = 1.93, 0.94–3.91).

Table 2.

Comparison of the frequencies of the genetic variant rs12252 of IFITM3 among influenza infected patients and controls

| Parameter | General Spanish population (n = 246)a,b |

Patients with IVI (n = 118)c |

Patients with mild IVI (n = 58) |

Hospitalized patients with PVP (n = 60) |

Patients with ICU admission (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HWE P value | 0.574 | 0.418 | 0.138 | 0.631 | 0.643 |

| Allele frequency, number (%) | |||||

| T | 475 (0.965) | 221 (0.936) | 108 (0.931) | 113 (0.942) | 63 (0.926) |

| C | 17 (0.0345) | 15 (0.063) | 8 (0.069) | 7 (0.058) | 5 (0.074) |

| Genotype frequency, number (%) | |||||

| TT | 229 (93.1) | 104 (88.1) | 51 (88.0) | 53 (88.3) | 29 (85.3) |

| CT | 17 (6.9) | 13 (11.0) | 6 (10.3) | 7 (11.7) | 5 (14.7) |

| CC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.84) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| dGeneral Spanish Population (n = 246) | |||||

| Allelic P value | … | 0.074 | 0.11 | 0.171 | 0.170 |

| Allelic OR (95 % CI) | 1.90 (0.88–4.08) | 2.07 (0.80–5.24) | 1.73 (0.63–4.56) | 2.22 (0.62–6.54) | |

| eIBS population (n = 107) | |||||

| Allelic P value | … | 0.130 | 0.13 | 0.262 | 0.169 |

| Allelic OR (95 % CI) | 2.01 (0.75–5.55) | 2.19 (070–6.92) | 1.83 (0.56–5.98) | 2.35 (0.56–8.90) | |

| fGeneral Spanish population and IBS population (n = 353) | |||||

| Allelic P value | … | 0.048 g | 0.11 | 0.149 | 0.167 |

| Allelic OR (95 % CI) | 1.93 (0.94–3.91) | 2.10 (0.85–5.08) | 1.76 (0.62–4.33) | 2.26 (0.65–6.31) | |

No significant differences were observed when genotype frequencies were compared

IFITM3 interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3, IVI influenza virus infection, PVP primary viral pneumonia, ICU intensive care unit, HWE Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, OR odds ratio (95 % confidence interval)

aDonors were recruited at four tertiary Spanish Hospitals

b33.28 ± 16.47 year-old; 44 % males

c45.81 ± 18.4 year-old; 57.6 % males

dComparisons included 246 Caucasian Spanish individuals from the general Spanish population of our study

eComparisons included 107 individuals from Iberian population in Spain, IBS (1000 Genomes project)

fComparisons included 353 individuals from the general Spanish population of our study together with the Iberian population in Spain, IBS (1000 Genomes project)

g P < 0.05

Mills et al. [14] did not find rs12252-C homozygotes in a group of 34 patients from the United Kingdom who required ICU admission due to severe H1N1 IVI. However, the authors found two rs12252-C homozygous individuals in a group of 259 Caucasian patients with mild influenza, and four in a group of 2,623 Caucasian controls who had never required hospital admission. Since allele frequencies were also similar in our population and in the study from Mills et al. [14], we combined our data with the data from their study. This comparison showed an increase of rs12252-C homozygotes in patients with mild IVI compared with control individuals: three out of 317 patients with mild influenza versus four out of 2,869 controls were homozygous for the rs12252-C allele (p = 0.025 by Fisher exact test; OR = 6.84, 1–40.6).

No significant differences were observed when patients with severe influenza (patients hospitalized with PVP or those requiring ICU admission) and the general population were compared (Table 2). No differences were either observed when only patients with A/H1N1pdm infection were compared separately (data not shown). When the different groups of patients were compared according to severity of infection (development of PVP, ARDS or acute respiratory failure, need of ICU admission or hospital mortality), no significant associations were found (data not shown).

Discussion

In 2012, Everitt et al. [9] found three homozygous individuals for the variant rs12252-C among 53 patients from the United Kingdom hospitalized with influenza (89.5 % H1N1pdm), resulting in a significant overrepresentation when compared with Europeans. Later, Zhang et al. [12] found a significant overrepresentation of rs12252-C homozygotes among 32 Chinese patients with severe H1N1pdm infection compared with 51 individuals with mild disease or population controls. These studies suggested that homozygosity for the IFITM3 rs12252-C allele was associated with a population-attributable risk for severe influenza of 5.4 % in Northern Europeans and 54.3 % for severe H1N1pdm infection in Chinese [9, 12]. Both studies included small sample sizes. Moreover, the association found by Everitt et al. [9] relied on imputed control genotypes, which may bias the frequencies when rare SNPs, such as rs12252, are studied. In addition, not all of their three rs12252-C homozygous patients have undergone population stratification analysis, thus not ensuring only Caucasian ancestors.

A more recent study did not find any rs12252-C homozygous in a group of 34 patients from the United Kingdom who required ICU admission due to severe H1N1 IVI [14]. By contrast, two rs12252-C homozygous individuals in a group of 259 Caucasian patients with mild influenza, and four in a group of 2,623 Caucasian controls who had never required hospital admission, were identified. The authors found a recessive association of the rs12252-C variant with mild influenza, but not with severe influenza. These data contrast with those of Zhang et al., who found an association with severe but not mild influenza [14]. Among our 118 patients with IVI, the only patient homozygous for rs12252-C was a 15-year-old girl who had a severe neurological disorder (West syndrome), a risk factor for severe influenza. However, after infection with H1N1pdm, she presented with mild influenza. Hence, no association with severe IVI was observed in our study. By contrast, we found a nonsignificant increase of the rs12252-C allele, but not genotypes, in patients with IVI compared to control Spanish individuals. In addition, when data from our study and those from Mills et al. [14] were analyzed together, a marginal significant association of homozygosity for rs12252-C with mild IVI was observed. These data suggest that, at least in populations of European origin, homozygosity for rs12252-C could confer an increased risk for IVI, but not for severe influenza. Since no patients with mild influenza were included in the study of Everitt et al. [9], their results might also arise as a consequence of the association of rs12252 with susceptibility to, rather than severity of, IVI.

It was suggested that IFITM3 plays a pivotal role in limiting the entry and replication of several viruses, including IAV, in humans and mice [9–11]. However, the impact of the rs12252-C polymorphism in viral restriction in vitro is also conflicting. Everitt et al. [9] reported that the IFITM3 rs12252-C polymorphism, coding for the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform, has reduced influenza virus restriction in vitro. However, no effect of Δ21 IFITM3 on the control of influenza virus restriction in vitro has been recently reported by Williams et al. [10].

Although our study includes the highest number of patients with severe IVI analyzed for the rs12252 polymorphism to date, it is limited by a relatively small sample size. Our control group may be considered a representative sample of the Spanish population rather than a representation of non-influenza infected individuals, since no data about IVI was available. In any event, this limitation would probably lead to underestimation of the association of the variant with susceptibility to IVI. No stratification analysis was performed in our study. However, it does not undermine the fact that, those patients homozygous for rs12252-C suffered from a mild influenza.

Overall, both the results of our study and those obtained by other authors suggest that homozygosity for the rs12252-C allele may predispose to mild, but not to severe, influenza, at least in patients of European origin. In view of the contradictory results observed in Asian and European populations, and the sample sizes of the groups of patients with influenza analyzed to date, further large-scale collaborative studies are required to clarify the role of IFITM3 rs12252 in IVI. A major issue is to know whether patients homozygous for rs12252-C should be actually considered at risk of severe influenza, and if they would require individualized measures in the case of IVI.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and their families for their trust. We also thank Nereida González-Quevedo and Yanira Florido for technical support and Consuelo Ivañez for their invaluable help.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Health [FIS PI10/01718, FIS PI12/01565 and FIS PI13/01456], with the funding of European Regional Development Fund-European Social Fund (FEDER-FSE); Fundación Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR); Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [fellowship to M.L.R. -FI11/00593] and Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [fellowship to E.H.R.]. The sponsors of the study had no role in designing the study, collecting, analyzing and interpreting the data, or writing the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the hospitals involved.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

M. López-Rodríguez, Email: martalopezguez@gmail.com

E. Herrera-Ramos, Email: faniya1@gmail.com

J. Solé-Violán, Email: jsolvio@gobiernodecanarias.org

J. J. Ruíz-Hernández, Email: pipiplons@yahoo.es

L. Borderías, Email: lborderiasc@gmail.com

J. P. Horcajada, Email: jhorcajada@parcdesalutmar.cat

E. Lerma-Chippirraz, Email: 95999@parcdesalutmar.cat

O. Rajas, Email: olga.rajas@gmail.com

M. Briones, Email: marisabriones@hotmail.com

M. C. Pérez-González, Email: mcpergon@gobiernodecanarias.org

M. A. García-Bello, Email: miguelgarciabello@gmail.com

E. López-Granados, Email: elopezg.hulp@salud.madrid.org

F. Rodriguez de Castro, Email: frodcasw@gobiernodecanarias.org

C. Rodríguez-Gallego, Phone: +34-871205120, Email: josecarlos.rodriguezgallego@ssib.es

References

- 1.Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Harper SA, Shaw M, Uyeki TM, et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1708–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broberg E, Nicoll A, Amato-Gauci A. Seroprevalence to influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus–where are we? Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1205–1212. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05072-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayward AC, Fragaszy EB, Bermingham A, Wang L, Copas A, Edmunds WJ, et al. Comparative community burden and severity of seasonal and pandemic influenza: results of the Flu Watch cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(6):445–454. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70034-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albright FS, Orlando P, Pavia AT, Jackson GG, Cannon Albright LA. Evidence for a heritable predisposition to death due to influenza. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:18–24. doi: 10.1086/524064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horby P, Nguyen NY, Dunstan SJ, Baillie JK (2013) An updated systematic review of the role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses (Suppl 2):37–41. doi:10.1111/irv.12079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Keynan Y, Malik S, Fowke KR. The role of polymorphisms in host immune genes in determining the severity of respiratory illness caused by pandemic H1N1 influenza. Public Health Genomics. 2013;16(1–2):9–16. doi: 10.1159/000345937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrera-Ramos E, López-Rodríguez M, Ruíz-Hernández JJ, Horcajada JP, Borderías L, Lerma E, et al. Surfactant protein A genetic variants associate with severe respiratory insufficiency in pandemic influenza A virus infection. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R127. doi: 10.1186/cc13934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everitt AR, Clare S, Pertel T, John SP, Wash RS, Smith SE, et al. IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature. 2012;484(7395):519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams DE, Wu WL, Grotefend CR, Radic V, Chung C, Chung YH, et al. IFITM3 polymorphism rs12252-C restricts influenza A viruses. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey CC, Huang IC, Kam C, Farzan M. Ifitm3 limits the severity of acute influenza in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(9):e1002909. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang YH, Zhao Y, Li N, Peng YC, Giannoulatou E, Jin RH, et al. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 genetic variant rs12252-C is associated with severe influenza in Chinese individuals. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1418. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Zhang A, Wan Y, Liu X, Qiu C, Xi X, et al. Early hypercytokinemia is associated with interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 dysfunction and predictive of fatal H7N9 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(2):769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321748111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills TC, Rautanen A, Elliott KS, Parks T, Naranbhai V, Ieven MM, et al. IFITM3 and susceptibility to respiratory viral infections in the community. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(7):1028–1031. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]