Abstract

Nosocomial pneumonia or hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) causes considerable morbidity and mortality. It is the second most common nosocomial infection and the leading cause of death from hospital-acquired infections. In 1996 the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published guidelines for empirical therapy of HAP. This review focuses on the literature that has appeared since the ATS statement. Early diagnosis of HAP and its etiology is crucial in guiding empirical therapy. Since 1996, it has become clear that differentiating mere colonization from etiologic pathogens infecting the lower respiratory tract is best achieved by employing bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or protected specimen brush (PSB) in combination with quantitative culture and detection of intracellular microorganisms. Endotracheal aspirate and non-bronchoscopic BAL/PSB in combination with quantitative culture provide a good alternative in patients suspected of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Since culture results take 2–3 days, initial therapy of HAP is by definition empirical. Epidemiologic studies have identified the most frequently involved pathogens: Enterobacteriaceae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus (‘core pathogens’). Empirical therapy covering only the ‘core pathogens’ will suffice in patients without risk factors for resistant microorganisms. Studies that have appeared since the ATS statement issued in 1996, demonstrate several new risk factors for HAP with multiresistant pathogens. In patients with risk factors, empirical therapy should consist of antibacterials with a broader spectrum. The most important risk factors for resistant microorganisms are late onset of HAP (≥5 days after admission), recent use of antibacterial therapy, and mechanical ventilation. Multiresistant bacteria of specific interest are methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus- baumannii, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Each of these organisms has its specific susceptibility pattern, demanding appropriate antibacterial treatment. To further improve outcomes, specific therapeutic options for multiresistant pathogens and pharmacological factors are discussed. Antibacterials developed since 1996 or antibacterials with renewed interest (linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin, teicoplanin, meropenem, new fluoroquinolones, and fourth-generation cephalosporins) are discussed in the light of developing resistance.

Since the ATS statement, many reports have shown increasing incidences of resistant microorganisms. Therefore, one of the most important conclusions from this review is that empirical therapy for HAP should not be based on general guidelines alone, but that local epidemiology should be taken into account and used in the formulation of local guidelines.

Keywords: Empirical Therapy, American Thoracic Society, Antibacterial Treatment, Cefpirome, Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score

Nosocomial pneumonia or hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) causes considerable morbidity and mortality. It is the second most common nosocomial infection and the leading cause of death from hospital-acquired infections.[1] Because diagnostic criteria differ considerably between various studies, only estimates of morbidity and mortality rates are available. The overall incidence of HAP is estimated to be between five and ten cases per 1000 hospital admissions, increasing 6- to 20-fold in mechanically ventilated patients.[2–4] Up to 28% of patients who develop pneumonia in a general ward require transfer to an intensive care unit (ICU).[5] Crude mortality rates for HAP range from 10% to 50%, with highest risks for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Estimates of mortality rates directly attributable to HAP are up to 30%.[6–8]

Because HAP constitutes a major clinical entity, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published a consensus statement in 1996 describing the current ideas of that time about empirical antimicrobial therapy. Since 1996, a large body of research on diagnosis and treatment of HAP has appeared in the literature, especially regarding the use of bronchoscopic techniques in identifying etiologic pathogens of HAP in individual patients, which has increased our knowledge of the etiology of HAP. That knowledge forms the basis for the design of empirical therapy. The aim of this review is to further rationalize the approach to empirical therapy and focus on relevant research that has appeared since the ATS statement.

Diagnosis Before Empirical Therapy

In general, pneumonia is diagnosed by the presence of a new lung infiltrate plus evidence that this infiltrate is of infectious origin. An infection is suspected if fever occurs together with purulent sputum and leukocytosis. However, several noninfectious causes can mimic pneumonia and should be ruled out: atelectasis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), adverse drug reactions, pulmonary thromboembolism, pulmonary hemorrhage, pulmonary fibrosis, lung carcinoma and congestive heart failure (pulmonary edema). Consequently, in only one-third of all ICU patients with pulmonary infiltrate is pneumonia thought to be the underlying etiology.[9,10] On the other hand, the absence of pulmonary infiltrates on the chest radiograph does not exclude pneumonia.[11] The clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS) can be helpful in supporting the clinician in identifying patients with HAP. The score is calculated from temperature readings, leukocyte counts, purulence of tracheal secretions, oxygenation (partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood [PaO2]/fraction of inspired oxygen [FIO2] ratio), aspects of pulmonary radiography, progression of pulmonary infiltrate, and quantitative culture of tracheal aspirate (see also section 3.2 and section 4).

By consensus HAP is defined as pneumonia occurring ≥48 hours after hospital admission but excluding any infection that is incubating at the time of admission.[4] Empirical antimicrobial therapy for HAP is based on epidemiological studies and designed specifically to cover microorganisms causing HAP. Therefore, successful empirical therapy greatly relies on an accurate diagnosis of HAP and its etiology.

In the pathogenesis of HAP, microaspiration of a small quantity of oropharyngeal secretion, previously colonized with potential pathogenic bacteria, is the most common route of entry of pathogens into the lower respiratory tract. Bacteria colonizing the oropharyngeal epithelial lining of hospitalized patients may be part of the patient’s endogenous flora, or may originate from other patients, hospital personnel, or environmental sources.[12–15] The risk of colonization of the oropharynx and upper respiratory tract by yeast or potentially pathogenic bacteria increases with the duration of hospital stay and is found in up to approximately 90% of intubated patients.[16–18] Moreover, the risk that this colonization encompasses resistant pathogens also increases. Especially in critically ill patients or patients on mechanical ventilation, once microaspiration has occurred, secretions are insufficiently eliminated from the lower respiratory tract, which can lead to the development of pneumonia.[19] As a result, it can be very difficult to differentiate colonizing pathogens in respiratory specimens from pathogens that are involved in active invasive infection.

Microbiology of HAP is crucial for making the diagnosis and initiating optimal therapy. Culture and Gram stain examination of expectorated sputum from patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can identify the etiologic pathogen with reasonable sensitivity and specificity. Most bacterial pathogens of CAP are easily differentiated from the normal oropharyngeal flora that inevitably is found in most cultures of expectorated sputum. In contrast, culture of expectorated sputum from hospitalized patients suspected of having bacterial HAP is frequently contaminated by colonizing microorganisms of the upper and lower respiratory tract. Although colonization of the upper respiratory tract by enteric Gram-negative bacteria is recognized as a risk factor for developing HAP,[20–23] a positive sputum culture does not differentiate between colonization and the etiologic pathogen of HAP in any given patient. In non-intubated and non-critically ill patients a sputum culture can, at most, identify suspected pathogens and their resistance pattern, but lacks sensitivity and specificity to identify the etiologic microorganism of HAP. Since colonization of the upper respiratory tract is most frequently found in critically ill or intubated patients, and because HAP in these groups is a life-threatening infection, a more reliable diagnostic sampling is needed in these patients.

Several bronchoscopic techniques for collection of secretions from the lower respiratory tract in patients suspected of VAP have been under evaluation for many years now. Since the 1996 ATS statement many reports have appeared about the diagnostic value of bronchoscopic techniques for endobronchial microbiological sampling. Although consensus about which technique can be best employed to diagnose VAP is lacking, both protected specimen brush (PSB) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in combination with quantitative culture have shown good results in diagnosing VAP.[24] Although most studies using invasive techniques in diagnosing HAP do so in patients suspected of VAP, bronchoscopic techniques may also play a crucial role in adapting antimicrobial therapy in non-mechanically ventilated patients suspected of HAP.[25]

Quantitative cultures were usually defined as bacterial growth of the etiologic pathogen of >103 cfu/mL for PSB or >103–4 cfu/mL for BAL.[26–31] Also, in a meta-analysis including 26 studies, PSB and BAL were both found to be reliable techniques to diagnose bacterial HAP.[32] However, no technique can reliably diagnose HAP for a patient already receiving antibacterial therapy.[32–34] One study has demonstrated that antibacterial therapy should be discontinued for at least 48 hours to obtain reliable specimens by PSB, BAL, protected BAL, or endobronchial aspiration.[33] The risk of discontinuation of therapy should outweigh the benefit of the diagnostic procedure (e.g. refractory cases of HAP). Alternatively, a diagnostic BAL or PSB in patients currently receiving antibacterial therapy can be performed, but the results should be interpreted with caution.[32–34]

Although bronchoscopically obtained quantitative BAL or PSB seem to offer maximal diagnostic reliability, in several studies other less invasive techniques have shown comparable sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing HAP.[35,36] In patients with an endotracheal tube, techniques that can be considered as alternatives to bronchoscopic techniques are endotracheal aspirate and non-bronchoscopic BAL/PSB in combination with quantitative culture. A major advantage is that these techniques can be employed by non-bronchoscopists and are less expensive. However, a major disadvantage of these techniques is the potential sampling error as a result of the blind technique without airway visualization. When using endotracheal aspirates, mere tracheal colonization is differentiated from positive cultures resulting from pneumonia by means of a certain cut-off value of the number of microorganisms per volume. However, if a cut-off of 106 cfu/mL is used many patients may not be identified (false-negative sampling).[37] On the other hand, diagnosing HAP with a lower cut-off value would result in unnecessary treatment of patients without HAP (false positives). Similarly, during non-bronchoscopic BAL or PSB the catheter is inserted blindly into the respiratory tract with the risk that microbiologic samples are obtained from unaffected segments of the lung, yielding false-negative cultures in patients with HAP.[38]

The diagnostic technique for HAP that is of best value in clinical decision-making probably depends mostly on the local situation. For bronchoscopic BAL or PSB to be of superior quality a hospital needs experienced bronchoscopists, a sufficiently equipped microbiology laboratory, the appropriate patient population and, above all, physicians who are willing to respond to the outcome: stop antibacterial treatment when confronted with a negative culture. Each hospital should devise a diagnostic protocol for HAP that is the most accurate and the most practical, knowing the pitfalls of the chosen technique.

Quantitative culturing can help to differentiate HAP from non-infectious lung infiltrates, but definite results cannot be expected before 48 hours after sampling. Alternatively, microscopic examination of Gram-stained samples of BAL can give early clues of HAP. The detection of intracellular organisms in the polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) and/or macrophages of BAL has been correlated to VAP with variable sensitivity.[24,34,38–43] Most studies used a cut-off of ≥5% of the cells positive for intracellular microorganisms. Although the Gram stain can be used for rapid diagnosis of VAP, adjustment of empirical therapy should be postponed until definite results of the quantitative culture are determined.[28,44]

Besides culturing of respiratory specimens, blood cultures and antigen tests should also be considered. Although only a minority of HAP patients produce positive blood cultures, these can help identify the causative pathogen in HAP. Similarly, pneumococcal urinary antigen tests can be helpful in cases of Streptococcus pneumoniae HAP.[45,46] However, although both techniques may be supportive in identifying the causative microorganism of HAP, they do not support the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Pathogens Associated with Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP)

Since microbiological identification of possible pathogens and their susceptibility pattern takes 2–3 days, initial antimicrobial therapy is, by definition, empirical. Even if respiratory culture results are available from before the onset of HAP, these are of limited value in guiding initial antimicrobial therapy decisions for patients with suspected VAP; in one study all the organisms ultimately responsible for pneumonia were recovered from only 35% of the specimens taken a median of 8 days before onset of pneumonia.[47]

The choice of empirical antimicrobial therapy is a balance between broad-spectrum antibacterial treatment with activity against a wide range of etiologic bacteria, and antibacterial treatment with very selective activity, which minimizes adverse reactions and the development of antibacterial resistance. To achieve this, empirical therapy is aimed at the most frequently isolated bacteria in HAP. However, certain patients are at risk for HAP with resistant pathogens. Consequently, if risk factors for resistant pathogenic organisms exist, extended-spectrum antibacterial therapy is recommended.

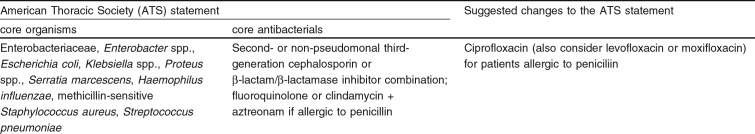

In 1996 the ATS published guidelines for empirical therapy of HAP in a consensus statement.[4] Based on the literature of that time, the most likely pattern of bacterial pathogens of HAP was assessed. The statement defines three treatment groups: (i) mild to moderate HAP without risk factors, onset any time, or severe HAP with early onset (table I); (ii) mild to moderate HAP with risk factors, onset any time (table II); and (iii) severe HAP with risk factors, early onset, or severe HAP with late onset (table III). All treatment groups are based on the different risk factors associated with certain pathogens.

Table I.

Empirical antibacterial therapy for mild to moderate hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) without risk factors and onset at any time or severe HAP with early onset

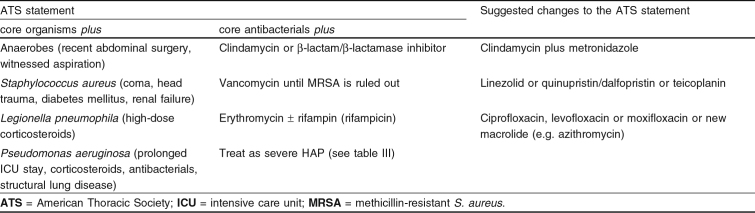

Table II.

Empirical antibacterial therapy for mild to moderate hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) with risk factors and onset at any time

Table III.

Empirical antibacterial therapy for severe hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) with risk factors and early onset or severe HAP with late onset

Enterobacteriaceae, Haemophilus influenzae, S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus are considered to be core pathogens; these microorganisms are most frequently isolated and should be covered by empirical therapy in any patient suspected of having HAP (table I). However, when choosing empirical therapy for individual patients, risk factors linked to the emergence of multiresistant bacteria need to be screened for. If a patient is at risk for certain resistant microorganisms, empirical therapy needs to be adjusted to achieve adequate antimicrobial activity (tables II and III).

Drug-resistant organisms that are of major concern in choosing empirical therapy of HAP are methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii, Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas) maltophilia and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Each of these organisms has its specific susceptibility pattern, demanding appropriate antibacterial treatment. Several studies have demonstrated that inappropriateness of initial empirical antibacterial treatment is significantly associated with an increased mortality.[48] Consequently, initial empirical therapy should cover all drug-resistant bacteria that can be expected in association with certain risk factors. However, most risk factors associated with developing HAP with resistant organisms are nonspecific and do not inform the clinician as to what specific resistant organism the patient is at risk from. Based on epidemiologic data describing organism-related prevalences, a risk profile can be outlined and empirical therapy can be adjusted accordingly. The incidence of specific resistant organisms varies greatly from country to country and even from one hospital to another.[49] For example, S. maltophilia infections are infrequent, except during outbreaks. As a result, optimal empirical therapy can only be achieved if up-to-date local epidemiology is taken into account.

Adequacy of initial antimicrobial therapy is not the only determining factor for outcome. Several studies have shown that multidrug-resistant microorganisms are associated with higher levels of mortality. However, only a few studies have adjusted for comorbidity or the severity of underlying disease. Rello et al.[50] found that even if initial antimicrobial therapy was active against P. aeruginosa, this organism was associated with an excess of mortality that could not be attributed to the severity of the underlying disease alone. Similarly, in a prospective case-control study Bercault and Boulain[51] identified 92 cases of HAP with sensitive, and 43 with multiresistant, etiologic pathogens. The latter group was significantly and independently associated with an increased mortality. Thus, multiresistant organisms are more than just resistant to certain antibacterials and, consequently, identifying risk factors associated with their presence is crucial in selecting the most vigorous empirical therapy.

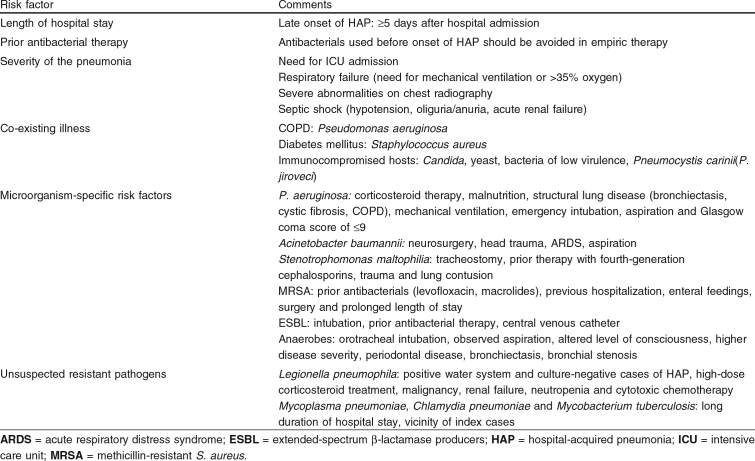

Risk factors for resistant pathogenic organisms are: (i) the length of hospital stay before the occurrence of HAP; (ii) prior antibacterial therapy; (iii) severity of the pneumonia; (iv) presence of co-existing illness; (v) microorganism-specific risk factors; and (vi) unsuspected resistant pathogens (table IV).

Table IV.

Risk factors for resistant etiologic pathogens in hospital-acquired pneumonia

Length of Hospital Stay

Probably the most important risk factor for resistant etiologic pathogens of HAP is prolonged stay in a hospital. Analogous to the ongoing process of colonization of the respiratory tract with potential pathogens, HAP occurring later during hospital admission is correlated to an increased risk for resistant pathogens obtained from the hospital environment.[18] Consequently, the ATS advises differentiation between early-onset and late-onset HAP. The ATS defines early-onset HAP as pneumonia occurring within 5 days of admission and late-onset HAP as pneumonia occurring ≥5 days after admission. The fifth day is taken as the ‘cut-off’ because most HAPs occurring before that time are caused by one of the core pathogens.[4,52]

Since 1996 several publications have appeared on microbiology of early- versus late-onset HAP, all applying bronchoscopic sampling techniques (BAL/PSB) in combination with quantitative cultures to identify ‘real’ cases of pneumonia. However, most studies were performed in patients admitted to an ICU and on mechanical ventilation. In an ICU study by George et al.[18] of 28 patients with VAP, late-onset VAP was defined as pneumonia developing after >5 days of mechanical ventilation. S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus spp. predominated in early-onset VAP and Pseudomonas spp. and MRSA in late-onset VAP. MRSA was only found in late-onset cases of VAP. However, prior use of antibacterials can lead to selection of resistant strains. This was not corrected for and may have influenced the outcome of this study. In another prospective study of 135 episodes of VAP, the use of broad-spectrum antibacterials prior to developing VAP was corrected for; results indicated that drug-resistant bacteria were independently associated with the duration of mechanical ventilation.[53] Multiresistant bacteria (non-fermenting enteric Gram-negative bacteria and/or MRSA) were not found before day 7 of mechanical ventilation. In a study by Rello et al.,[49] 9 of 89 episodes of VAP occurring before day 7 of mechanical ventilation were caused by multiresistant bacteria. However, P. aeruginosa was found in three patients, all experiencing COPD. COPD is a known risk factor for VAP with P. aeruginosa. Therefore, empirical therapy for patients with COPD should include anti-pseudomonal coverage, especially in patients with a long-term history of COPD with recurrent use of antibacterials. The other six episodes of VAP were caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. These cases were all found in two specific hospitals with a high prevalence of these bacteria. Again, this emphasizes that each hospital should be aware of local epidemiology of multiresistant bacteria. In hospitals with a high prevalence, empirical therapy should be adapted accordingly, especially in patients with severe HAP and those at increased risk of resistant bacteria.

In a prospective comparative analysis of 3668 ICU patients, Ibrahim et al.[54] identified 235 patients with early-onset HAP (≤96 hours of ICU admission) and 185 patients with late-onset HAP. P. aeruginosa was the only pathogen found significantly more frequently in patients with late-onset HAP compared with early-onset HAP. However, P. aeruginosa was isolated from patients with early-onset HAP in greater numbers than expected and differences between both groups were small: 25% and 38% in early- and late-onset HAP, respectively. P. aeruginosa was found more frequently in patients with early-onset HAP than would be expected based on the ATS statement. The authors discussed whether anti-pseudomonal coverage should also be considered in some cases. However, this study defined the onset in relation to time of ICU admission (early-onset HAP was pneumonia occurring within the first 96 hours of ICU admission), in contrast to the ATS, which defined the onset in relation to the time of hospital admission.[54] In this study more than 50% of early-onset HAP was caused by P. aeruginosa, MRSA, S. maltophilia, Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter spp. The high incidence of multiresistant bacteria was because of hospitalization prior to ICU admission. These studies demonstrate that the definition of early- and late-onset HAP should not be based exclusively on time of admission to an ICU. Since colonization of the respiratory tract commences at admission to the hospital, this also defines the time of onset. Although mechanical ventilation is a risk factor for the development of HAP, it also seems to enhance the colonization process of resistant pathogens.[55] Therefore, the time a patient has been on mechanical ventilation should also be taken in account when assessing the risk for HAP with resistant microorganisms.

Prior Antibacterial Therapy

Prior use of antibacterials has previously been linked to the development of HAP.[56,57] Moreover, prior antibacterial treatment is associated with HAP caused by multiresistant bacteria. A few studies that appeared prior to the ATS statement suggested that HAP developing after antibacterial treatment was more likely to be caused by multiresistant pathogens.[58–60] In the study by Rello et al.[60] in 1993, from analysis of 129 consecutive episodes of VAP it was concluded that prior use of antibacterials was associated with a significantly greater mortality. Further logistic regression analysis established that this was only independently related to the presence of multiresistant pathogens. Although confounding factors were adjusted for, this study included many patients with a history of COPD, which itself is associated with multiresistant microorganisms and repeated use of antibacterials.

Several studies appearing after the ATS statement confirm these earlier reports. Trouillet et al.[53] conducted a study in 1998, analyzing 135 consecutive episodes of VAP. In this study prior antibacterial use was also identified as an independent variable associated with VAP caused by potentially resistant bacteria. Moreover, not only the presence or absence of antibacterial therapy before the onset of pneumonia, but also the specific use of broad-spectrum antibacterial agents such as third-generation cephalosporins, imipenem, or fluoroquinolones, was independently related to antimicrobial resistance of VAP. Moreover, in 2002 Trouillet et al.[61] demonstrated by multivariate analysis that not only was the occurrence of P. aeruginosa linked to previous antibacterial use, but that the occurrence of piperacillin-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa could also be linked to prior antibacterial use, especially that of fluoroquinolone. Since piperacillin is a major empirical antipseudomonal drug, in patients having received fluoroquinolones prior to the development of HAP, empirical therapy for HAP with risk factors should not include piperacillin.[61] Moreover, after having received fluoroquinolones prior to the onset of HAP, these antibacterials should also be avoided in empirical therapy since the existence of fluoroquinolone-resistant P. aeruginosa is to be expected.

The role of previous use of antibacterials becomes even more pronounced during outbreaks with multiresistant bacteria. Husni et al.[62] showed that during an outbreak with multiresistant Acinetobacter spp., prior use of ceftazidime was significantly more frequent in patients who developed HAP with this microorganism compared with patients without HAP.[62] Similarly, during an outbreak with MRSA, patients who developed HAP with MRSA had received prior antibacterials significantly more often than patients who developed HAP with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) infection.[63]

Severity of the Pneumonia

The ATS guidelines for empirical therapy make a distinction between patients with mild to moderate HAP and patients with severe HAP. When severe HAP occurs within 5 days of admission, it is likely to be caused by a ‘core pathogen’. Therapy should be directed against H. influenzae and MSSA, but not against the highly resistant enteric Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa or Acinetobacter spp. In contrast, if severe HAP occurs ≥5 days after admission the more resistant microorganisms may be involved.

Analogous to CAP, severe HAP is defined by: (i) the need for admission to an ICU; (ii) respiratory failure (need for mechanical ventilation or >35% oxygen); (iii) severe abnormalities on the chest radiography (progression, multilobarity or cavitation of the pneumonia); or (iv) severe sepsis with signs of shock (hypotension, oliguria/anuria, acute renal failure requiring dialysis).[4] Severe sepsis should be defined by clinical parameters and not by the presence of bacteremia. Although blood cultures should always be drawn in patients with serious infections, the presence of bacteremia does not predict complications, is not related to the length of stay, and does not identify patients with more severe illness in HAP.[64] Mild or moderate HAP is less clearly defined. Patients who do not need mechanical ventilation, >35% oxygen, intensive care treatment and do not show signs of septic shock should generally be considered as mild. In addition, several scoring systems can help to distinguish mild from severe cases (e.g. APACHE [Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation] II, SAPS [Simplified Acute Physiological Score] II).[65]

Few studies have examined the risk factors that determine the relationship between severity of pneumonia and outcome. In 1997, Rello et al.[50] showed that crude mortality in patients with nosocomial pneumonia appeared to be related to the degree of organ dysfunction at diagnosis rather than to any characteristics of the pneumonia. The presence of resistant pathogens seemed to be more important than the severity of the pneumonia. Even if the initial antibacterial therapy was active against P. aeruginosa, this organism was associated with an excess of mortality that could not be attributed to the severity of the underlying disease alone.[50]

In contrast to what is suggested by the ATS statement, there is insufficient evidence to establish severity of HAP as an independent risk factor for resistant pathogens. However, since patients with severe pneumonia are at increased risk of mortality, adequacy of initial antibacterial therapy may be of utmost importance. Therefore, in patients with severe HAP of early onset, initial antibacterial treatment with a spectrum against local resistant pathogens of high prevalence should be considered.

Presence of Co-Existing Illness

As mentioned in sections 2.1 and 2.2, COPD is a known risk factor for VAP with P. aeruginosa as a pathogen. In addition, patients with any kind of structural lung diseases (e.g. bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis) are at risk for multiresistant pathogens, especially P. aeruginosa. The fact that P. aeruginosa is found in a large percentage of these patient groups is possibly explained by the fact that these microorganisms survive best in humid environments, which are found in mucus-retaining bronchiectic pockets. In patients with cystic fibrosis, once P. aeruginosa or Burkholderia cepacia have established in the airways it is almost impossible to eradicate them; consequently, 30–40% of patients with cystic fibrosis will have long-term pseudomonal infection.[66] Therefore, empirical therapy for patients with COPD should include anti-pseudomonal coverage, especially in patients with a long-term history of structural lung disease with recurrent use of antibacterials.

In immunocompromised hosts, specific resistant bacteria may play a role in developing HAP. S. maltophilia has recently emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen in immunocompromised cancer patients and transplant recipients. Risk analysis has shown that mechanically ventilated ICU patients receiving antibacterials, especially carbapenems, are at increased risk of colonization/infection.[67] Similarly, Legionella spp. have a predilection for infecting immunocompromised patients, and transplant recipients have the highest risk. Moreover, Legionella spp. have been the most common cause of nosocomial pneumonia among transplant recipients at selected medical centers.[68] Neutropenic patients (PMNLs <500/mm3), in particular, are at risk of fungal infections. Most guidelines recommend broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy in neutropenic patients if they become febrile for any reason.[69] Consequently, especially in neutropenic patients who remain febrile and develop pulmonary symptoms during the course of broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, fungal pneumonia should be considered.[70] Although Pneumocystis carinii (P. jirovecii) is best known for infecting HIV-infected patients with low CD4 counts (<200/mm3), patients with hematological malignancies, solid tumors, collagen-vascular diseases and transplant recipients are also at risk.[71] Particularly in at-risk patients who have a protracted hospital stay, specimens obtained by bronchoscopy should also be tested for P. carinii.

Microorganism-Specific Risk Factors

Although no single risk factor can accurately predict the occurrence of specific resistant pathogens, the ATS statement does mention certain circumstances that increase the risk of certain types of resistant bacteria involved in HAP. Since 1996 few studies have focused on microorganism-specific risk factors.

Although previous antibacterial treatment and prolonged hospital stay are risk factors for HAP caused by P. aeruginosa (as discussed in sections 2.1 and 2.2), corticosteroid therapy, malnutrition, structural lung disease (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis) and mechanical ventilation may also increase the risk for P. aeruginosa.[4] The ATS statement based the risk factors for P. aeruginosa on a study by Niederman,[22] which did not investigate cases of HAP but cases of colonization with P. aeruginosa. However, recent data confirm that patients with COPD are at increased risk for P. aeruginosa HAP, and that this is the strongest risk factor after prior use of antibacterials and prolonged hospital stay.[72] Similarly, in 2002 Trouillet et al.[61] identified the presence of underlying fatal medical conditions as an independent factor associated with HAP with P. aeruginosa. In 2000, Akca et al.[73] demonstrated in 33 cases of VAP by P. aeruginosa that early-onset HAP can also be caused by these resistant bacteria and that this was significantly associated with emergency intubation, aspiration and a Glasgow Coma score of ≤9. However, early-onset VAP was defined by the time of intubation and, as a result, prolonged hospital stay may still be the leading risk factor. Furthermore, culture data were based on tracheal aspirates and could merely have resulted from colonization of the tube.

The use of mechanical ventilation is associated with P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. in particular. One pathogenic mechanism described is the difference in adherence by different bacterial species to different catheter surfaces. In contrast to urinary catheters, the role of biofilm in respiratory tube adherence and pathogenesis of VAP is less clear.[74] Nevertheless, water condensate in the endotracheal tube may favor certain bacterial species such as P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp.

In a study of 148 episodes of VAP, Baraibar et al.[75] demonstrated that A. baumannii was independently associated with neurosurgery, head trauma, ARDS and aspiration. In contrast to P. aeruginosa or Enterobacteriaceae, in this study A. baumannii seemed not to be related to co-morbid illness, severity of disease, or exposure to antibacterial therapy. However, this study was of relatively small sample size and in 16% of all HAP episodes the bacterial diagnosis remained uncertain, despite invasive bronchoscopic techniques. The underlying mechanism of these findings could not be explained from these results.

In addition to P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia has also been identified as a high-risk pathogen; VAP with S. maltophilia is associated with increased length of ICU stay and mortality. In addition, S. maltophilia carries intrinsic resistance to most antibacterials.[76] In a multivariate analysis, patients with tracheostomy, cefepime exposure and severe trauma with lung contusion were significantly more at risk for S. maltophilia HAP.[77]

Since S. aureus is one of the major pathogens of HAP, MRSA is one of the major concerns in the design of empirical treatment protocols. Although debated for a long time, a recent meta-analysis has provided evidence that MRSA is associated with a significant increase in mortality in comparison with similar infections with MSSA.[78] Recent data indicate that the MRSA incidence is increasing despite recommendations for isolation precautions.[79] No type of infection has a predilection for MRSA; however, in contrast to MSSA, prior antibacterials (especially levofloxacin and macrolides), previous hospitalization, enteral feeding, surgery and length of stay before culture were independently associated with MRSA infection.[80] During a 5-year period, Pujol et al.[81] studied all VAP cases caused by MRSA and found that MRSA caused exclusively late-onset VAP, while MSSA caused both early-onset and late-onset VAP.[81] In patients with HAP who have had prior antibacterial treatment and who are admitted to a hospital with a high prevalence of MRSA, have a long hospital stay and are on mechanical ventilation, empirical treatment should have activity against MRSA.

Since the ATS statement in 1996, an increasing number of reports have appeared on outbreaks with ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp. or Escherichia coli.[82–85] Non-ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp. and E. coli are generally susceptible to most β-lactam antibacterials. In contrast, ESBL-producing strains are resistant to most β-lactams with the exception of carbapenems. Furthermore, recently even imipenem-resistant Klebsiella strains have been observed.[86,87] Intubation, previous antibacterial therapy, and central venous catheter insertion have been identified as risk factors for infection with ESBL-producing strains.[88–90] Up to now, only patients admitted to the hospital or residence in long-term care facilities were thought to be at risk of acquiring ESBL-producing Klebsiella or E. coli. However, Einhorn et al.[91] showed that in 14% of all ESBL cases in Chicago, Illinois, USA, in 2002, the infection was acquired in the community by patients who resided at home. Although ESBL-producing bacteria constitute a major therapeutic problem most reports could not demonstrate an increased mortality in patients who developed infections with ESBL-producing organisms compared with patients with infections with non-ESBL-producing organisms.[89,92] Consequently, during an outbreak with an ESBL-producing microorganism, patients with HAP are at risk, especially those who have received prior antibacterial therapy, and those with late-onset and ventilator-associated HAP.

In the ATS guidelines thoracoabdominal surgery and witnessed aspiration are pointed out as risk factors for developing HAP with anaerobic microorganisms. This was based on a study by Bartlett et al.[93] performed in 1986 on cultures of pleural effusions, blood and nonquantitative cultures of tracheal aspirates. This study needs careful interpretation because based on today’s knowledge of bronchoscopic sampling, the anaerobes found in 35% of cases of HAP may well have been the result of sampling of high airway colonization.[94] Because of the technical difficulties and relatively high costs, most microbiological laboratories do not routinely employ anaerobic culture techniques for respiratory specimens. However, sometimes even simple measures can improve the diagnosis of anaerobic infections; PSB samples should be transported in thioglycolate instead of saline.[95] Overall, the role of anaerobes in HAP may be underexposed in the literature. However, a few studies have appeared since the ATS statement, using bronchoscopic sampling techniques and anaerobic culturing. The main anaerobic strains isolated were Prevotella melaninogenica (36%), Fusobacterium nucleatum (17%), and Veillonella parvula (12%). VAP with anaerobes occurred significantly more often in patients who were orotracheally intubated than those nasotracheally intubated and significantly more frequently in early-onset VAP than late-onset VAP. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the presence of altered levels of consciousness, higher disease severity, and admission to the medical ICU were the factors independently predisposing to the development of VAP with anaerobes.[96] In contrast, Marik and Careau[97] performed a similar study and found only one anaerobic microorganism in 75 patients with HAP. Also, in 12 patients with observed aspiration, no anaerobes were recovered from the bronchoscopically obtained samples. Eight years after the ATS statement, too few studies have appeared to establish the exact role of anaerobes in HAP. However, their presence as co-pathogens should always be suspected, especially in intubated patients or after aspiration. Analogous to CAP, patients with HAP and periodontal disease, bronchiectasis or bronchial stenosis (by tumor, stenosis or foreign body) may also be at increased risk for anaerobic pulmonary infection.[70] In contrast to HAP, the role of anaerobes in lung infections is mostly accepted in obstructive pneumonia and lung abscess.[70,94] On the other hand, anaerobes are usually of low virulence and many patients commonly recover from HAP without receiving specific anti-anaerobic therapy.

Uncommon Pathogens Resistant to Empirical Therapy

Although relatively rare, nosocomial legionnaires’ disease can occur in outbreaks as well as in single patients. As is stated in the ATS guidelines, empirical treatment for nosocomial pneumonia does not include specific antibacterials against Legionella pneumophila. As a result, mortality from legionnaires’ disease is high in patients who receive inappropriate antibacterial therapy. Two reports by Chang et al.[98] and Goetz et al.[99] demonstrate that routine environmental cultures play a major role in stimulating the application of Legionella laboratory testing. In both studies positive water-system samples subsequently identified unsuspected patients with nosocomial legionnaires’ disease.[99] As this confirms the ATS guideline, clinicians and microbiologists should indeed bear in mind the need to also test for legionnaires’ disease in patients with severe or culture-negative HAP. This is especially true if patients are at risk for legionnaires’ disease during high-dose corticosteroid treatment, malignancy, renal failure, neutropenia or cytotoxic chemotherapy.[4] In 2000, a study by Stout et al.[100] revealed that long-term care residents are at risk of acquiring nosocomial legionnaires’ disease in the presence of a colonized water system. Consequently, nosocomial legionnaires’ disease should be suspected if a sudden flare-up of incidence is noted.[12,101,102] Therefore, urine antigen tests for L. pneumophila type 1 should be readily available if even the slightest possibility of legionnaires’ disease exists (see also section 4).

Other more rare bacterial causes of HAP with microorganisms requiring specific antibacterials are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[98,103] These pathogenic microorganisms are frequently identified in community-acquired respiratory tract infections but rarely in HAP. These microorganisms can only be identified by serologic testing or specific culture techniques that are not routinely used in laboratory testing for HAP. However, if a patient is admitted to the hospital for a long period, the risk of infection with these pathogens may increase, especially if the patient is cared for in the vicinity of an index case with M. tuberculosis, for example.

Antibacterial Treatment of HAP

Empirical Antibacterial Treatment

Once the clinical diagnosis of HAP is made and risk factors have been assessed, empirical treatment guidelines can be obtained using the algorithms that the ATS published in 1996 (see tables I, II and III). These antibacterial recommendations were based on well designed, controlled clinical trials whenever possible.[4] When sufficient data were lacking, the spectrum of antimicrobial activity and pharmacokinetic data were taken into account. All guidelines for empirical therapy are focused on the initial treatment of patients with HAP; as soon as possible pathogens are identified and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns are available, empirical therapy should be re-evaluated. Obviously, if susceptibility testing of possible pathogens demonstrates resistance, empirical therapy should be changed to antibacterials with an effective spectrum of activity. On the other hand, if microbiological test results show susceptible pathogens (e.g. H. influenzae or S. pneumoniae), empirical therapy must be changed to antibacterials with a narrower spectrum.[104] This should be done not only for reasons of suppressing global development of antibacterial resistance, but also to minimize the risk of serious adverse effects of broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy such as pseudomembranous colitis and selection of, and super infection with, multiresistant bacteria.[105]

The major goal of empirical therapy guidelines is to ensure that initial antibacterial therapy has sufficient activity against the unknown pathogen causing HAP. Inappropriateness of initial antibacterial treatment is associated with an increased mortality.[56,106] Recent studies, based on modern sampling techniques, also show that adequacy of initial antibacterial treatment, based on susceptibility tests, is of great importance for clinical efficacy. Studying 119 nosocomial infections in four ICUs, Zaidi et al.[107] found that the major risk factors for mortality were inadequate antibacterial treatment and development of VAP. Similarly, Luna et al.[64] performed bronchoscopic sampling and multivariate analysis on 162 cases of VAP and found that inadequacy of initial antimicrobial therapy and age >50 years were the only factors associated with mortality. Although it is probably appropriate to employ general guidelines for empirical therapy for HAP, it cannot be stressed enough that local epidemiologic surveys should be performed to monitor for possible resistant pathogens. Similarly, during outbreaks of resistant strains, the local empirical antibacterial policy should be re-evaluated.

Part of the adequacy of initial therapy is also determined by time management. In one study, in almost 31% of all patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for VAP, the initial appropriate antibacterial treatment was delayed for 24 hours.[108] In logistic regression analysis, delayed antibacterial treatment was identified as an independent risk factor associated with increased mortality. The most common reason for deferral of therapy was a delay in writing the antibacterial orders!

In the ATS algorithm, the first step is to define the severity of illness as either mild to moderate or severe, analogous to treatment guidelines for CAP.[109] In patients with mild to moderate illness recommended empirical therapy is directed against the core pathogens (table I), independent of length of hospital admission. However, if specific risk factors for infection are present, specific antibacterials should be added to the ‘core empirical therapy’ (table II). Patients with severe HAP will fall into the description of tables I or III. The treatment will depend mostly on whether the patient developed HAP early, within 5 days of hospitalization (table I), or late (≥5 days after admission) [table III]. Antibacterial treatment described in table III displays activity to resistant microorganisms for which risk factors are found during patient assessment.

Mild to Moderate HAP without Risk Factors or Severe HAP with Early Onset

Under mean general epidemiologic circumstances, according to ATS guidelines in patients with mild to moderate HAP without risk factors and onset anytime, and in patients with severe HAP without risk factors and of early onset, adequacy of empirical antibacterial therapy is achieved using ‘core antibacterials’ (table I). The definition of ‘core antibacterials’ is that they have activity against enteric Gram-negative bacteria, H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae and MSSA. Since P. aeruginosa is only seldom found in this patient group, ‘core antibacterials’ need not have anti-pseudomonal activity. First-choice antimicrobial therapy for these core pathogens would consist of either a cephalosporin or a β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination. cephalosporins of the second generation (e.g. cefotetan, cefoxitin, cefuroxime) or non-pseudomonal third generation (e.g. ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftizoxime) are recommended. β-Lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam. In a study by Speich et al.[110] the efficacy of piperacillin/tazobactam, the most recently developed β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination, was compared with that of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the treatment of severe pneumonia.[110] The agents proved to be equally and highly efficacious treatments. However, only a minority of pneumonias in this study was of nosocomial origin and consequently Enterobacter spp., Proteus spp. and Serratia spp. were not encountered as core pathogens.

β-Lactam antibacterials form the basis of empirical therapy for HAP without risk factors (table I). The major mechanism of bacterial resistance to these recommended β-lactams is bacterial production of β-lactamases that can hydrolyze β-lactam antibacterials to inactive compounds. Different types of β-lactamases are produced by different bacteria. Second-generation cephalosporins are resistant to the β-lactamases produced by certain strains of H. influenzae, Klebsiella, E. coli and S. aureus. Although these β-lactamases can hydrolyze amoxicillin, ticarcillin or piperacillin, when combined with a β-lactamase inhibitor, hydrolysis is prevented and the antibacterial retains its activity. However, β-lactamases produced by certain strains of Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter (class C, type AmpC) are also capable of hydrolyzing amoxicillin despite the presence of clavulanic acid. Paradoxically, clavulanic acid is a stronger inducer of AmpC β-lactamases, which it cannot inhibit, than sulbactam and tazobactam. However, the real concern lies with strains that produce Amp C β-lactamases in large quantities (‘hyperproducers’), leaving only the carbapenems, certain fourth-generation cephalosporins (e.g. cefepime and cefpirome), fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides as alternatives.[85,111] These so called ‘de-repressed’ mutants have become very prevalent, with incidences of 25–40% in major hospitals in North America and Western Europe.[112–114] The risk of selecting derepressed mutants during therapy is approximately 20% when third-generation cephalosporins are used to treat bacteremia caused by Enterobacter spp.[115] and is probably higher in pneumonia.[112] However, induction does not usually take place within a couple of days of therapy. Therefore, if after a few days culture results indicate Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter spp. or Serratia spp. as the pathogen, in severe cases a change of therapy should be considered. If local epidemiologic data demonstrates high incidences of one of these species, β-lactamase production may already have been induced and henceforth empirical therapy should altogether be switched to therapy as is suggested in table III.

Mild to Moderate HAP with Risk Factors

If patients with mild to moderate HAP are at risk for resistant pathogens, independent of the time of onset, empirical therapy can be adapted according to table II. Although the role of anaerobes in HAP is not clear, under some circumstances (described in section 2.6 and table IV) specific anaerobic antimicrobial therapy should be considered. In a relatively small study in patients with HAP, the most frequently isolated anaerobic bacteria were Prevotella spp., which were more frequently resistant to cefotaxime (37%), ceftazidime (50%), and ciprofloxacin (32%) than usually reported in the literature.[116] Sixty-six percent of these strains produced β-lactamases. From these results it could be concluded that patients who had received empirical anti-anaerobic antimicrobial therapy had a significantly better outcome after 10 days.[116] Moreover, since penicillin-resistant anaerobic organisms, usually Bacteroides spp., can also be encountered in infections of the lower respiratory tract,[117] specific anaerobic treatment may be warranted. Of the core antibacterials (table I) only cefoxitin and cefotetan (second-generation cephalosporins)[118] and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations possess sufficient activity against anaerobes including Bacteroides fragilis. Therefore, if a patient is suspected of HAP with possible involvement of anaerobes, first-choice empirical therapy should consist of these drugs or any combination with clindamycin or metronidazole. However, several case-controlled studies have suggested that metronidazole monotherapy of anaerobic pulmonary infections is less effective than clindamycin as a single drug.[119–121] Since clindamycin is also active against many Gram-positive microorganisms (e.g. S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and β-hemolytic streptococci) this would be the first choice in patients with HAP with increased risk for anaerobic pneumonia. However, clindamycin has limited or no activity against some strains of B. fragilis. Therefore, in selected cases of HAP with a high suspicion of anaerobic microorganisms (e.g. observed aspiration or post-obstruction pneumonia) combination therapy with clindamycin and metronidazole can be considered.

In hospitals where MRSA is not highly prevalent, empirical therapy consisting of a second-generation (cefalotin or cefazolin) or third-generation cephalosporin or a β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor will have sufficient activity against S. aureus. However, in North and Latin America, respectively, 44% and 46% of all S. aureus isolates from patients with pneumonia consisted of MRSA.[122,123] Similar rates are found in Europe and Japan.[79,124] Therefore, if MRSA is highly prevalent and the patient is at risk of HAP with S. aureus, empirical therapy should consist of a core antibacterial plus vancomycin.[125] From earlier studies quinupristin/dalfopristin has been considered to be an option for unresponsive MRSA infections, where few proven treatment options exist.[126] In cases of patient allergy or intolerance to glycopeptides, in one study quinupristin/dalfopristin proved to be equally safe, but somewhat less efficacious than vancomycin.[127] Other alternatives are teicoplanin and linezolid (see section 3.1.4). However, vancomycin is not the drug of choice for patients infected with MSSA. In a study by Gonzalez et al.,[63] mortality was significantly higher among MSSA-infected patients treated with vancomycin than among those treated with cloxacillin (47% vs none). Hence, if culture results show susceptible S. aureus as a single pathogen, therapy should preferably be switched to flucloxacillin or nafcillin monotherapy.

According to ATS guidelines, patients receiving high-dose corticosteroid therapy are at risk for legionnaires’ disease.[4] However, based on recent literature, patients with malignancy, renal failure, neutropenia or cytotoxic chemotherapy are also at risk for legionnaires’ disease, especially if the hospital water system is known to be infected.[4] Especially in severe cases of legionnaires’ disease, empirical treatment with core antibacterials has insufficient activity against L. pneumophila. If there is a risk for legionnaires’ disease, specific empirical treatment should be considered. Instead of erythromycin plus rifampicin, as is stated by the ATS, recent literature suggests that fluoroquinolones or newer macrolides (e.g. azithromycin) should now be considered first-choice therapy for legionnaires’ disease.[128–130] Rifampin (rifampicin) may have additional efficacy in severe cases of HAP.

Severe HAP with Risk Factors and Early Onset or Severe HAP with Late Onset

In 1996 the ATS recommended that patients with severe HAP with risk factors and early onset, and patients with severe HAP with late onset should be treated according to table III. In these patients, next to the core pathogens, the main concern is the high prevalence of P. aeruginosa and other multiresistant bacteria. Particularly in patients with mechanical ventilation, HAP caused by these microorganisms is associated with increased mortality.[131,132] Because bactericidal synergy against Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp. has been shown when carbenicillin and an aminoglycoside are combined, the use of an antipseudomonal β-lactam (piperacillin, ticarcillin, ceftazidime, or imipenem) in combination with an aminoglycoside remains the preferred therapeutic approach where possible.[133] Similarly, when considering time-kill curves in vitro, the combination of ciprofloxacin plus piperacillin plus tazobactam achieved greater killing than other combinations or monotherapy against P. aeruginosa.[134] Whether synergistic activity against P. aeruginosa can be achieved or not, there is another reason for combining two different antibacterial categories; when P. aeruginosa is implicated, monotherapy, even with broad-spectrum antibacterials, is associated with a rapid increase in resistance and a high rate of clinical failure. Therefore, for pseudomonal HAP, combination therapy consisting of an antipseudomonal β-lactam plus an aminoglycoside or a fluoroquinolone (e.g. ciprofloxacin) is advised.[135]

During outbreaks with ESBL-producing microorganisms, carbapenems are the first-choice empirical therapy for patients suspected of HAP with late onset or other risk factors, depending on the characteristics of the strains involved. Although β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations can be used for some susceptible strains, even for the most potent (piperacillin/tazobactam), resistance in Europe has risen significantly from 31% to 63% over a period of 4 years.[136] Fluoroquinolones can be used as an alternative empirical treatment, but one should realize that both in Europe and the US up to 31% of ESBL-producing isolates are also ciprofloxacin-resistant.[83,136] When fluoroquinolones are used in cases of high ESBL risk, adding an aminoglycoside to the empirical treatment may improve activity against possible ciprofloxacin-resistant strains.[111]

Newer Antibacterials and Treatment Strategies

Antibacterials developed since 1996 or antibacterials with renewed interest for the treatment of HAP are linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin, teicoplanin, meropenem, new fluoroquinolones and fourth-generation cephalosporins.

Since the ATS statement a new class of antibacterials has been developed: oxazolidinones. Oxazolidinones having activity against Gram-positive bacteria are of most interest in the treatment of HAP with MRSA. In a large epidemiological study involving the ICUs of 25 European university hospitals (SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program) resistance to oxacillin was found in 39% of all collected S. aureus strains. However, all these isolates were fully susceptible to linezolid and vancomycin.[137] Two studies have examined the use of linezolid as an alternative treatment to vancomycin: in both studies patients received linezolid plus aztreonam or vancomycin plus aztreonam as empirical treatment for HAP.[138,139] Clinical cure and microbiological eradication rates were equivalent between treatment groups. Similar results were documented for HAP patients with MRSA.[138,140] Linezolid is well tolerated and has a major advantage over vancomycin in that oral formulations are also available.[141] Another possible alternative treatment for HAP with MRSA is quinupristin/dalfopristin.[142] Similar to linezolid, quinupristin/dalfopristin also has in vitro activity against most MRSA strains, comparable to teicoplanin and vancomycin.[143] In one study by Fagon et al.,[127] 31% of MRSA cases treated with quinepristin/dalfopristin were clinically successful. Nonetheless, there was 44% success in the vancomycin-treated group. More studies will be needed to examine the clinical potentials of these drugs as empirical therapy for HAP with a high risk of MRSA. Teicoplanin is an effective and safe alternative for vancomycin in the treatment of resistant Gram-positive infections. However, the use of teicoplanin in the treatment of HAP has not been investigated. Consequently, teicoplanin should only be considered in selected cases of MRSA where other alternative treatment is contraindicated.

Meropenem is the second carbapenem since the development of imipenem/cilastatin. It shows enhanced Gram-negative activity relative to imipenem/cilastatin and often retains activity against strains resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and imipenem/cilastatin (including P. aeruginosa). Furthermore, in contrast to imipenem/cilastatin it has far less epileptogenic and nephrotoxic activity, making it especially suitable for treatment in patients with underlying central nervous system pathology or renal dysfunction.[144,145] Similar to imipenem, meropenem has shown good efficacy as monotherapy in patients with HAP.[146]

Recent epidemiologic studies have shown that Pseudomonas spp. also retain good susceptibility to fourth-generation cephalosporins. Moreover, multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae also show high rates of susceptibility to cefepime and cefpirome.[137,147] This may explain why empirical therapy for VAP with cefepime or cefpirome was relatively superior to ceftazidime in some studies.[148,149] Although ceftazidime remains a superior anti-pseudomonal drug, especially in hospitals with high incidences of cases with ceftazidime-resistant P. aeruginosa, fourth-generation cephalosporins (cefepime and cefpirome) can be considered as empirical therapy in cases of severe HAP.

The number of HAP cases with S. maltophilia is increasing and constitutes a major therapeutic problem.[67] S. maltophilia is resistant against many antibacterials used as empirical therapy. Consequently, prior antibacterial treatment is a risk factor for HAP with S. maltophilia.[77] In one study antibacterial susceptibility testing revealed that isolates were most sensitive to sulfamethoxazole (80%), chloramphenicol (75.5%) and ceftazidime (64.5%).[150] In contrast, a recent report has shown that, in vitro, more strains are sensitive to minocycline, doxycycline and moxifloxacin. More than 70% of strains were resistant against ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin, ticarcillin and aztreonam. Only 25% of all strains were resistant against trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Thus, in patients highly suspected of HAP with S. maltophilia (e.g. during an outbreak), it is now recommended to initiate empirical treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and ticarcillin/clavulanic acid in combination.[151]

In the search for new antimicrobial therapies for Acinetobacter spp., unconventional antibacterial treatment strategies have been tested. Wolff et al.[152] studied the efficacy of β-lactams/β-lactamase inhibitors and rifampin in a mouse model for A. baumannii pneumonia. The best survival rates (≥80%), even when mice were infected with a multiresistant strain, were obtained with regimens containing rifampin and sulbactam. This suggests that non-classical combinations of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor and rifampin should be considered for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia caused by multiresistant A. baumannii.[152] This was confirmed by Montero et al.[153] using an experimental pneumonia mouse model with carbapenem-resistant strains: colistin appeared far less potent in reducing lung bacterial counts, clearance of bacteremia, and survival than imipenem, sulbactam, rifampin and tobramycin.[153] From another mouse model study, doxycycline plus amikacin was suggested as an alternative to imipenem in the therapy of A. baumannii pneumonia.[154]

Of all the new fluoroquinolones that have been developed since the ATS statement, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin have been of particular interest concerning the treatment of CAP. They offer excellent activity against Gram-negative bacilli and improved Gram-positive activity (e.g. against S. pneumoniae and S. aureus) over ciprofloxacin. Furthermore, these agents may result in cost savings especially in situations where, because of their potent broad-spectrum activity and excellent bioavailability, they may be used orally in place of intravenous antibacterials. However, there is only limited experience with levofloxacin and moxifloxacin in the treatment of HAP. In one large study (n = 438) with most patients on mechanical ventilation, levofloxacin monotherapy proved equally efficacious as imipenem/cilastatin in both microbiologic eradication rate and clinical success rate.[155] The diagnosis of HAP was based on clinical symptoms, radiographic findings and respiratory cultures. However, patients in this study were also included based on a positive sputum culture, making the diagnosis of HAP less reliable. Furthermore, patients with severe disease were excluded and the mean APACHE II scores in both groups were relatively low. Another point of concern is raised by recent reports that have shown failure of treatment with levofloxacin in several cases of pneumococcal pneumonia.[156,157] Therefore, the use of levofloxacin and moxifloxacin in HAP should be restricted to selected cases pending the results of future investigations.

Duration of Antibacterial Therapy

At the time of the ATS statement, few data were available to support solid recommendations on duration of antibacterial therapy for HAP. A major step towards tailor-made antimicrobial therapy would be identifying clinical parameters that can indicate when it is safe to stop antibacterial treatment in any given patient. Few studies have investigated this issue. Dennesen et al.[158] studied the time course of several infectious parameters in patients with VAP after the start of appropriate antibacterial treatment. They found that most improvements in temperature, leukocyte counts and oxygenation (PaO2/FIO2 ratio) were observed within the first 6 days of antibacterial treatment. Although H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae were eradicated from tracheal aspirates, Enterobacteriaceae, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa persisted despite antimicrobial susceptibility.[158] Therefore, eradication of the latter microorganisms from the lower respiratory tract does not provide a useful means of monitoring the clinical effect of antimicrobial treatment.

In another study, Singh et al.[159] used a clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS) by Pugin et al.[160] to determine the likelihood that any given patient’s clinical findings were caused by pneumonia. The score is calculated from temperature readings, leukocyte counts, purulence of tracheal secretions, oxygenation (PaO2/FIO2 ratio), aspects of pulmonary radiography, progression of pulmonary infiltrates and quantitative culture of tracheal aspirates. Singh et al.[159] used this score to discriminate all ICU patients in whom VAP was considered unlikely (CPIS score ≤6) from those that were likely to have VAP (CPIS score >6). Patients with CPIS ≤6 were randomized to receive either ciprofloxacin for 3 days or standard care (antibacterials for 10–21 days). After 3 days patients in the ciprofloxacin group were re-evaluated; all patients with CPIS >6 received further treatment for pneumonia, but all patients with CPIS ≤6 at 3 days had antibacterial treatment stopped. Antibacterials were continued beyond 3 days in 90% (38 of 42) of the patients in the standard therapy group compared with 28% (11 of 39) in the experimental therapy group (p = 0.0001). In patients in whom CPIS remained ≤6 at the 3-day evaluation point, antibacterials were still continued in 96% (24 of 25) in the standard therapy group but in none (0 of 25) of the patients in the experimental therapy group (p = 0.0001). Mortality and length of ICU stay did not differ despite a shorter duration and lower cost of antimicrobial therapy in the experimental group. More surprisingly, antimicrobial resistance, or superinfections, or both, developed in 14% (5 of 37) of patients in the experimental group versus 38% (14 of 37) of patients in the standard therapy group (p = 0.017).

Penetration of antibacterials to the site of infection is important in achieving antibacterial concentrations beyond the minimal inhibiting concentration of the pathogen involved. The ratio between drug concentration in respiratory secretions and serum, the fractional penetration, is about 10–20% for β-lactam antibacterials, 20–40% for aminoglycosides and 50–100% for the fluoroquinolones.[161,162] Macrolides, tetracyclines and trimethoprim also show good penetration into bronchial secretions.[163] However, controversy remains about which parameter is the most relevant derivative of tissue concentration: antibacterial concentration in bronchial secretions or alveolar lining fluid.[164] Administering the correct dosage of antibacterials is of utmost importance in the empirical therapy of HAP. Although most antibacterials are marketed as ‘one dose for all’, each patient may require an individualized dosage. To ensure good initial antibacterial tissue concentrations, initial antibacterial therapy of HAP should be administered intravenously. Switching to oral administration should not be considered before the first signs of clinical improvement. In contrast to research on HAP, several reports on treatment of CAP have appeared since 1996 investigating an early switch from intravenous to oral antibacterials.[165–169] Although patients with CAP have different microorganisms and a dissimilar pathogenesis at play, certain parallels can be made. It appears that hospitalized (non-ICU) patients with mild CAP can be treated safely with only a short course (≤ 3 days) of intravenous antibacterials and that a subsequent treatment of 7 days with oral antibacterials is sufficient in most cases.

Although insufficient data are available to make solid recommendations on the duration of treatment in patients with HAP, from the aforementioned studies several points of attention can be made. Because no gold standard exists on making the diagnosis of HAP and because physicians are unwilling to risk missing a treatable infection, a large proportion of patients diagnosed with HAP will either receive too many antibacterials or do not need antibacterial treatment at all. Furthermore, the total duration of antibacterial treatment and the duration of intravenous antibacterial treatment can probably be shortened in many cases of mild HAP, especially in cases of HAP caused by S. pneumoniae or H. influenzae, and in patients showing normalization of temperature, leukocyte counts and oxygenation.

Failure of Antibacterial Treatment of HAP

Even with optimal and adequate empirical antibacterial therapy HAP remains a disease with high mortality. In most patients, clear clinical improvement should not be expected within 24 hours after the start of antibacterial treatment. Dennesen et al.[158] have shown that leukocyte counts, temperature and oxygenation normalize, on average, 6 days from the start of antibacterials. However, the first signs of improvement of clinical parameters were found within 48 hours. Consequently, failure of treatment cannot be established within 24 hours after start of therapy. However, in severe cases of VAP or in patients on mechanical ventilation because of HAP, who experience ongoing deterioration of clinical parameters, switching antibacterial treatment to a more broad-spectrum regimen should first be considered after 24 hours. This is especially true in patients for whom microbiological results remain inconclusive. In mild to moderate cases, changing antibacterial therapy should not be considered until at least 48 hours have passed since the start of therapy. The CPIS score can help to monitor the development of VAP (or patients with HAP on mechanical ventilation) after start of therapy. Luna et al.[170] have shown that in patients who received adequate antibacterial treatment (no resistant microorganisms were cultured) and recovered from VAP, the CPIS score was significantly improved at day 3.[170] In contrast, patients who had inadequate antibacterial treatment and did not survive VAP, did not display improved CPIS scores at day 3. In two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures, clinical improvement or worsening was most accurately depicted by the PaO2/FIO2 ratio. In another study with 298 patients with HAP, multivariate analysis revealed that six variables were associated with decreased likelihood of clinical success; >65 years of age, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, mechanical ventilation for >5 days, multilobar pneumonia, and bacteremic pneumonia.[127] Patients who fail to respond, or experience clinical deterioration, should be re-examined carefully, and thought should be given to the possibility of other noninfectious processes.[171] In cases of raised suspicion of resistant pathogens, fresh endobronchial specimens for culture should be obtained.

Certain factors may play a role in the failure of treatment. Although a bacterial etiology of HAP is the most frequent, viruses are also potential pathogens.[172–174] Clinically, viral pneumonias are difficult to differentiate from bacterial pneumonias. Since viral agents are not routinely tested for, the incidence of viral pneumonias is almost certainly underestimated.[173] Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections contribute substantially to the morbidity and mortality associated with viral pneumonia, especially in young children and the elderly.[174,175] Other viruses associated with HAP are parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus and measles.[176] Patients at risk for developing serious pneumonia with these viruses are neonates and immunocompromised patients. Extra suspicions for a viral etiology of HAP should be raised during and following the annual community outbreaks of influenza and RSV.[177]

Other microorganisms that should be excluded in patients with treatment failure or deterioration despite antibacterial treatment are L. pneumophila and fungi. Especially in severe pneumonia, negative urine antigen tests for L. pneumophila can almost rule out (nosocomially acquired) legionnaires’ disease. In rare cases of infections with type 2 L. pneumophila, and in mild cases, antigen tests lack sensitivity and can give a (false) negative result.[178,179] Patients with neutropenia or patients receiving intensive treatment with corticosteroids (e.g. patients with COPD) are at risk for more acute presentations of Aspergillus spp. infections. However, even in non-immunosuppressed, non-neutropenic patients, severe VAP resulting from Aspergillus spp. has been reported.[180] Consequently, especially in high-risk patients with extended hospital stay and failure of antibacterial treatment, cultures for fungi of BAL or PSB specimens, and serum fungal antigen tests should be considered.

Conclusions

Both the ATS statement and the many reports on the diagnosis and treatment of HAP that have appeared since then, have focused on patients admitted to ICUs and/or those on mechanical ventilation. Although this subgroup consists of patients with severe nosocomial pneumonia, more research on non-ICU patients is needed to explore whether the same guidelines apply to less severe cases of HAP. From the large body of literature on the diagnosis of HAP it can be concluded that bronchoscopic techniques, in combination with quantitative cultures, are superior to other more conservative techniques to obtain respiratory samples and to establish early diagnosis. Detection of intracellular microorganisms in lower respiratory tract specimens has been demonstrated to be a reliable marker for the early diagnosis of HAP. Furthermore, microscopic examination can give a first impression of the type of pathogen involved.

The core pathogens mentioned by the ATS can still be regarded as the main target of empirical therapy. In order to identify those patients at risk of HAP with multiresistant microorganisms, more risk factors have been identified since the ATS statement; prolonged stay in the hospital and prior antibacterial therapy seem to be the most important risk factors for resistant pathogens. However, increasing numbers of resistant pathogens are reported. Since epidemiology can vary from one hospital to another, epidemiological surveys should be conducted to assess locally encountered pathogens of HAP. Consequently, general guidelines (e.g. ATS guidelines) should be adapted to local epidemiology.

Although some new antibacterials have been marketed since 1996, the development of new potent antibacterials remains a point of concern. Several alternative treatments may prove effective in cases of resistant HAP. To minimize the use of antibacterials, future studies should focus on finding clinical parameters and making guidelines that can help the clinician reduce the duration of antibacterial treatment.

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors believe there are no potential conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this review.

References

- 1.Gross PA. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect. 1987;2(1):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George DL. Epidemiology of nosocomial ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14(3):163–9. doi: 10.1086/646705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kollef MH. Epidemiology and risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia: emphasis on prevention. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20(3):653–70. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996.

- 5.Greenaway CA, Embil J, Orr PH, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia on general medical and surgical wards in a tertiary-care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18(11):749–56. doi: 10.1086/647529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming CA, Balaguera HU, Craven DE. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia: focus on prophylaxis. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(6):1545–63. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagon JY, Chastre J, Hance AJ, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated patients: a cohort study evaluating attributable mortality and hospital stay. Am J Med. 1993;94(3):281–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leu HS, Kaiser DL, Mori M, et al. Hospital-acquired pneumonia: attributable mortality and morbidity. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(6):1258–67. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh N, Falestiny MN, Rogers P, et al. Pulmonary infiltrates in the surgical ICU: prospective assessment of predictors of etiology and mortality. Chest. 1998;114(4):1129–36. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meduri GU, Mauldin GL, Wunderink RG, et al. Causes of fever and pulmonary densities in patients with clinical manifestations of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 1994;106(1):221–35. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler KL, Sinclair KE, Henderson VJ, et al. The chest radiograph in critically ill surgical patients is inaccurate in predicting ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am Surg. 1999;65(9):805–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]