Abstract

Diabetes leads to reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, resulting in endothelial dysfunction. However, overproduction of nitric oxide due to hyperglycaemia is associated with oxidative stress and tissue damage. The objective of this study was to characterise nitric oxide production (NO) and added nitrite and nitrate (NO2-+NO3-) concentration in the blood and urine of patients with and without diabetic nephropathy. A total of 268 patients with type 1 diabetes and 69 healthy subjects were included. Diabetic nephropathy was defined as macroalbuminuria and/or estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 ml/min/1.73 cm2. NO2-+NO3- concentration was measured by Griess reaction. Production of NO was detected by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Blood NO was demonstrated to be higher (P<0.001) and serum NO2-+NO3- was lower (P=0.003) in patients with type 1 diabetes and no nephropathy vs. healthy subjects. However, serum NO2-+NO3- concentration in patients with diabetes and nephropathy did not differ from the levels observed in healthy controls. Urine excretion of NO2-+NO3- was significantly decreased in patients with nephropathy, compared with patients without diabetic kidney disease (P=0.006) and healthy subjects (P=0.010). A significant positive correlation was observed between urine NO2-+NO3- and estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with type 1 diabetes (P=0.002) and healthy subjects (P=0.008). Estimated glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria and diabetic nephropathy status were significant predictors of the whole blood NO and NO2-+NO3- in serum and urine in patients with type 1 diabetes, as identified by linear regression models. The present study concludes that NO metabolism is impaired by type 1 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy.

Keywords: NO, nitrite, nitrate, diabetic nephropathy, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

Introduction

The number of patients with diabetes mellitus constantly increases. Vascular complications, including diabetic nephropathy are major reasons for increased morbidity and mortality among patients with diabetes (1). Chronic hyperglycaemia leads to the formation of advanced glycosylation end products, activation of protein kinase C, polyol pathway and glucose autoxidation. These processes are sources of increased oxidative stress, which leads to damage in vasculature and tissues (2). Active research is on-going in the area of other potential mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy, including nitric oxide (NO) metabolism (3).

NO is a pleiotropic molecule important to a number of physiological and pathological processes in humans. In physiological conditions, effects of NO are tissue-dependent and include vasorelaxant, antithrombotic and antibacterial. However, high amounts of NO are associated with pro-inflammatory processes (4). The adverse effects of NO result mainly from peroxynitrite (ONOO-), a product of the interaction of NO with the superoxide anion and a potent toxin. Overproduction of NO and ONOO- is associated with DNA damage, enzyme dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, decreased NO bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction (2,5-11).

Experimental data confirm increased NO and ONOO- production in tissues of animals with diabetes mellitus (5,7,8,12). Existing studies on changes in NO metabolism coupled to diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in humans often demonstrate the opposite findings. Reduced serum nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-) synthesis was described in patients with diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetes (13), and in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and glomerular hyperfiltration (14). In contrast, increased serum NO2-+NO3- has been reported in patients with T1D and albuminuria (15) and in children with T1D (16). Only a few studies have described changes of concentration of NO metabolites in both the serum and urine of T1D patients, despite the importance of both measurements (14,16). Whereas serum NO2-+NO3- reflects mainly endothelial NO production although it might be influenced by dietary NO2- and NO3- (17), data on urine NO2-+NO3- may reflect the intensity of NO synthesis in the kidney circulation (14) and thus provide information for research on diabetic nephropathy (3).

NO is an unstable molecule, which is metabolized to NO2-+NO3- within seconds. Therefore, the majority of human studies report data on concentrations of NO2-+NO3- in serum and/or urine (13,18). Data on NO production [which can only be measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy or amperometric electrodes (19-21)] ex vivo in humans with diabetes is lacking, due to technical difficulties of the above methods.

To summarize, the understanding of derangements of NO metabolism in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy in T1D is limited (5,15,16,18).

To reduce the gap in this knowledge, the present study describes data on simultaneous measurement of concentrations of NO in whole blood by EPR spectroscopy and its metabolites NO2-+NO3- in serum and urine of T1D patients with and without diabetic nephropathy.

Materials and methods

Patients and ethics

The present study was a part of LatDiane: Latvian prospective diabetic nephropathy study. LatDiane recruits' patients with T1D (defined as the age of diagnosis <40 years, with insulin treatment initiated within 1 year of diagnosis and C-peptide level <0.3 nmol/l). The study is in line with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and received the Latvian Central Ethics Committee's approval no. 01-29.1/3. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate. Patients recruited between September and May each year between 2013 and 2016 with a diabetes duration >1 year were included (N=268) in this study. Patient characteristics are shown in Table I. The control group was formed of volunteers (n=69) without previously diagnosed diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, who were invited to participate in this study in 2013-2014. Exclusion criteria for both groups of patients were pregnancy, acute or chronic urinary infection, signs of acute inflammation (C-reactive protein >5 mg/l, fever, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate), history of chronic kidney disease apart from diabetic nephropathy, oncologic or rheumatologic diseases, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), current usage of antibiotics or history of immunosuppressive treatment.

Table I.

Characteristics of subjects.

| Characteristics | Healthy subjects (N=69) | Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy (N=246) | Type 1 diabetes and nephropathy (N=22) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men/women, % (N) | 38/62 (26/43) | 46/54 (112/134) | 46/54 (10/12) |

| Age, years | 23 (21-26) | 36 (24-47)a | 33 (27.5-47)a,b |

| Diabetes duration, years | - | 14 (6.2-22) | 22 (15.2-28.8)b |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.6 (20.6-26) | 24.4 (21.8-27.8) | 23.5 (21.4-24.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 120 (110-125) | 124 (117-135)a | 136 (126-149)a,b |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75 (70-80) | 80 (71-85)a | 89 (80-91)a,b |

| Hypertension, % (N) | 1(1) | 41(101)c | 76(19)c,d |

| On ACEI/ARB, % (N) | 0 (0) | 24(61) | 32(8) |

| HbA1c% | 5.3 (5.1-5.5) | 8.3 (7.4-9.6)a | 10.1 (8.3-11.1)a,b |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 34.4 (32.2-36.6) | 67.2 (57.4-81.4)a | 86.9 (67.2-97.8)a,b |

| Triglycerides, mmol/l | 0.7 (0.6-1.1) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4)a | 1.2 (1.0-1.9)a,b |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.2 (3.7-4.8) | 4.9 (4.1-5.5)a | 4.8 (4.0-6.0) |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/l | 2.3 (1.8-2.7) | 2.7 (2.1-3.3) | 2.5 (2-3.5) |

| On statins, % (N) | 0 (0) | 10(26) | 12(3) |

| Smoking, % (N) | 17(12) | 26(64) | 28(7) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 108.6 (96.5-121.8) | 110.8 (97.4-123.1) | 85.7 (56-98.6)a,b |

| Albuminuria, %(N)e: | |||

| Normoalbuminuria | 100(69) | 80(197) | 9(2)d |

| Microalbuminuria | 0 (0) | 17(42) | 9(2) |

| Macroalbuminuria | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 81(18)d |

| Urine albumin/creatinine ratio, mg/mmol | 0.3 (0.2-0.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.6)a | 72.8 (46.8-152.2)a,b |

| Chronic kidney disease, % (N) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 28(7)d |

| Fundus oculi exam, % (N): | - | 17(43) | 32(7) |

| No retinopathy | 59(144) | 18(4)d | |

| Non-proliferative retinopathy | 24(59) | 50(11)d | |

| Proliferative retinopathy and status post LPC | |||

| Diabetic polyneuropathy, % (N) | - | 38(94) | 72(18)c |

| Vascular hard event, % (N) | 0 (0) | 6(15) | 12(3) |

Mean values are shown as median (q0.25-q0.75).

aP<0.05 vs. ‘healthy subjects’;

bP<0.05 vs. ‘Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy’, pairwise Wilcoxon test;

cP<0.05 vs. ‘Healthy subjects’;

dP<0.05 vs. ‘Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy’, Chi-square prop test;

emissing 7 from ‘Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy’ group. Chronic kidney disease-eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Vascular hard event-history of acute myocardial infarction, coronary bypass/percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, stroke, amputation, or peripheral vascular disease. LPC, pan-retinal laser photocoagulation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (CKD-EPI); ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Definitions

Albuminuria was assessed using two out of three urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio measurements in morning spot urine according to the guidelines of the National Kidney foundation (22).

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (23). Chronic kidney disease was defined as eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2. ESRD was defined as eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73 m2, dialysis or kidney transplantation. Diabetic nephropathy was defined as macroalbuminuria and eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Arterial hypertension was defined as regular usage of antihypertensive drugs, or systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg (18.7 kPa) and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg (12.0 kPa). Diabetic retinopathy was defined as proliferative diabetic retinopathy or status after panretinal-laser photocoagulation, based on conclusion of the fundus oculi examination performed by an ophthalmologist. Cardiovascular disease was defined as history of acute myocardial infarction, coronary bypass/percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, stroke, amputation, or peripheral vascular disease. Diabetic polyneuropathy was defined based on electromyography data (reporting peripheral sensory, senso-motor or motor neuropathy). Smoking was self-reported, patients currently smoking at least one cigarette per day were referred to the ‘smokers’ group. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/[height (m2)].

Biochemical parameters

Total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins and triglyceride (enzymatic colour reaction), HbA1c (high-pressure liquid chromatography), C-reactive protein (immuno-turbidimethric method) and albumin to creatinine ratio in urine (immunoturbidimetric test and enzymatic kinetic reaction) were measured in certified clinical laboratories.

Measurement of NOin whole blood

NO production was measured essentially as described (24). A total of 20 mg diethylthiocarbamate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added to 1 ml fresh blood, stirred and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then the mixture was aspirated into an insulin syringe and frozen in liquid nitrogen, the frozen cylinder was extruded from the syringe and placed in a quartz finger Dewar flask ER 167 FDS-Q (Bruker Corporation) filled with liquid nitrogen. NO concentration was detected measuring the NO component in the spectrum of Fe-DETC-NO (g=2.031) and compared with the calibration curve. To build up the calibration curve different quantities of NaNO2 (final concentrations 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 100 µM) were mixed with DETC (33 mg/ml) and FeSO4. 7H2O (3.3 mM), an excess of Na2S2O4 (2 M) was added to the mixture. The EPR spectra were taken as described above. Thus, the calibration curve contained both negative and positive controls.

EPR spectra were recorded in liquid nitrogen using the EPR spectrometer Radiopan SE/X2544. Conditions of EPR measurements were: 2.5 mW microwave power, 9.24 GHz microwave frequency, 100 kHz modulation frequency, 0.5 mT modulation amplitude, and 5x105 receiver gain. Limits of detection for NO were 5-50 ng/g tissue. The observed deviation between measurements was 5-10%.

Measurement of NO2-+NO3- in patients' serum samples

Serum samples were deproteinised, using Amicon Ultra filters for centrifugation (cat. no. UFC800324; EMD Millipore). NO2-+NO3- was measured with the Cayman's Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric assay kit (cat. Nr 780001; Cayman Chemical Company) and Perkin Elmer Lambda 25 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Inc.) (21). NO2-+NO3- concentration was quantitated using the nitrate standard curve (final concentrations 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 µM), which was performed according to the protocol in the kit. The detection limit of sample was 2.5 µM. Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation are 3.4 and 2.7%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All measurements for NO and NO2-+NO3- were performed in triplicate, and the mean values were used for analysis. NO levels in whole blood was measured in 269 samples, NO2-+NO3- levels in serum was measured in 310 samples, and NO2-+NO3- levels in urine was measured in 308 samples. At the initial analysis stage, chi-square test for proportions for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for quantitative variables (Table I) were used. As none of the variables analysed followed normality (tested using the Shapiro test), nonparametric statistical procedures were used. Data are presented as medians with the respective interquartile range. The equality of medians was tested using the and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Wilcoxon sum rank test for pairwise comparisons. For multiple comparisons P-value correction method by Holm was used. Healthy subjects differed from both groups of patients with T1D in age and HbA1c. Therefore, ANCOVA procedure on ranks was used to adjust for age and other potential confounders (gender, BMI, HbA1c% and smoking), although it did not lead to any significant P-value changes.

Other differences between the groups (duration of diabetes, blood pressure, lipids, eGFR, albuminuria and prevalence of complications of diabetes) were attributable to diagnosis of T1D or diabetic nephropathy, therefore adjustment for these parameters was not performed.

A Spearman correlation coefficient was used to study association between markers of NO metabolism. Regression analysis was performed only for data of patients with T1D. A total of three linear regression models with either whole blood NO, or serum and urine NO2-+NO3- as dependent variables were used. Initially, full models adjusted for age, sex, diabetes duration, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, smoking, HbA1c, lipids, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, eGFR, diabetic nephropathy status were used. To identify predictors with major impact on nitric oxide metabolism markers, a stepwise regression model based on AIC selection was applied. All statistical tests were using R version 3.6.1(25).

Results

Characteristics of study groups

Study subjects included 268 patients with T1D and 69 healthy subjects. Patients with T1D were stratified according to the presence of diabetic nephropathy. Anthropometric and clinical characteristics of three groups (healthy subjects, patients with T1D without diabetic nephropathy, patients with T1D with diabetic nephropathy) are summarised in Table I. Subjects in the control group did not have any chronic diseases, except hypertension in one case.

Concentration of NO in the whole blood of patients with T1D and healthy subjects

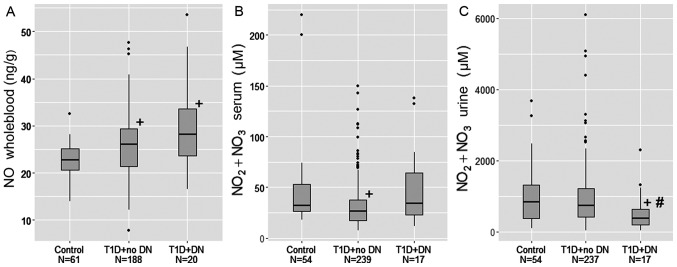

The concentration of whole blood NO was significantly increased in patients with T1D, compared with controls (P<0.05). Within T1D patients, the presence of diabetic nephropathy did not lead to a further increase in NO (Fig. 1A and Table II).

Figure 1.

Markers of NO metabolism in biological fluids of study subjects. (A) Concentration of NO in study groups. (B) Concentration of serum NO2-+NO3- in study groups. (C) Concentration of NO2-+NO3- in urine in study groups. +P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. T1D+no diabetic nephropathy. T1D, type 1 diabetes; DN, diabetic nephropathy; NO, nitric oxide; NO2, nitrite; NO3, nitrate.

Table II.

Markers of nitric oxide metabolism in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes with and without nephropathy.

| Groups | NO, ng/g whole blood | NO2-+NO3-, µM, serum | NO2-+NO3-, µM, urine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy subjects, n | 22.8 (20.6-25.1), 69 | 32.1 (26.5-53.3), 39 | 842.7 (370.9-1304.8), 39 |

| Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy; n | 26.0 (21.3-29.3), 185a | 26.3 (17.6-37.5), 246c | 729.0 (417.9-1215.8), 245 |

| Type 1 diabetes and nephropathy; n | 28.2 (23.7-33.5), 15b | 34.0 (22.9-64.5), 22f | 365.4 (188.8-626.7), 21d,e |

Data are presented as median and interquartile range.

aP<0.001 vs. ‘Healthy subjects’;

bP=0.006 vs. ‘Healthy subjects’;

cP=0.003 vs. ‘Healthy subjects’;

dP=0.006 vs. ‘Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy’;

eP=0.010 vs. ‘Healthy subjects’;

fP=0.098 vs. ‘Type 1 diabetes without nephropathy’. Kruskal Wallis test followed by pairwise Wilcoxon test. Wilcoxon test was followed by Ancova on ranks for adjustment for age, gender, BMI, HbA1c%, smoking. NO, nitric oxide; NO2, nitrite; NO3, nitrate.

Concentration of NO2-+NO3- in the serum of patients with T1D and healthy subjects

The concentration of NO2-+NO3- in the serum was significantly decreased (P=0.003) in patients with T1D and no nephropathy compared with healthy subjects. However, in patients with T1D and nephropathy, serum concentration of NO2-+NO3- did not differ from the control group (Fig. 1B and Table II).

Concentration of NO2-+NO3- in the urine of patients with T1D and healthy subjects

NO2-+NO3- in urine did not differ between patients with uncomplicated T1D and controls. Within the T1D group, the concentration of NO2-+NO3- in urine was significantly decreased in patients with diabetic nephropathy, when compared with patients without diabetic nephropathy (P=0.006) and healthy subjects (P=0.010; Fig. 1C and Table II).

Correlation between parameters of nitric oxide metabolism in patients with T1D and healthy subjects

A strong positive significant correlation was observed between eGFR and urine NO2-+NO3- in healthy subjects (R=0.688; P=0.008). This correlation was also significant, although weak in patients with type 1 diabetes (R=0.190; P=0.002).

A medium positive significant correlation was observed between NO2-+NO3- in serum and NO2-+NO3- in urine in healthy subjects (R=0.492; P=0.002) and T1D patients without diabetic nephropathy (R=0.559; P<0.001), but not in T1D patients with diabetic nephropathy (R=0.351; P=0.120).

In patients with diabetes, a weak negative correlation was observed between diabetes duration and urine NO2-+NO3- (R=-0.131; P=0.032) and a weak positive correlation between albuminuria and serum NO2-+NO3- (R=0.150; P=0.015).

No correlation was observed between blood NO and NO2-+NO3- in urine and serum (Table III).

Table III.

Correlation of nephropathy-related parameters with markers of nitric oxide metabolism.

| Groups | Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Correlation coefficient (R) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy subjects | eGFR | NO2-+NO3- urine | 0.688 | 0.008 |

| Type 1 diabetes | eGFR | NO2-+NO3- urine | 0.190 | 0.002 |

| Healthy subjects | eGFR | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.090 | 0.762 |

| Type 1 diabetes | eGFR | NO2-+NO3- serum | -0.051 | 0.406 |

| Healthy subjects | eGFR | NO | -0.215 | 0.222 |

| Type 1 diabetes | eGFR | NO | -0.099 | 0.165 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Diabetes duration | NO2-+NO3- urine | -0.131 | 0.032 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Diabetes duration | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.049 | 0.425 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Diabetes duration | NO | -0.029 | 0.684 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Albuminuria | NO2-+NO3- urine | -0.064 | 0.304 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Albuminuria | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.150 | 0.015 |

| Type 1 diabetes | Albuminuria | NO | 0.094 | 0.184 |

| Healthy subjects | NO2-+NO3- urine | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.492 | 0.002 |

| Type 1 diabetes + no DN | NO2-+NO3- urine | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.559 | <0.001 |

| Type 1 diabetes + DN | NO2-+NO3- urine | NO2-+NO3- serum | 0.351 | 0.120 |

| Healthy subjects | NO | NO2-+NO3- serum | -0.253 | 0.120 |

| Type 1 diabetes + no DN | NO | NO2-+NO3- serum | -0.095 | 0.200 |

| Type 1 diabetes + DN | NO | NO2-+NO3- serum | -0.339 | 0.216 |

| Healthy subjects | NO | NO2-+NO3- urine | -0.216 | 0.188 |

| Type 1 diabetes + no DN | NO | NO2-+NO3- urine | -0.042 | 0.570 |

| Type 1 diabetes + DN | NO | NO2-+NO3- urine | -0.332 | 0.246 |

R-Spearman correlation coefficient. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; DN, diabetic nephropathy; albuminuria, albumin/creatinine ratio in morning spot urine; NO, nitric oxide; NO2, nitrite; NO3, nitrate.

Predictors of markers of NO metabolism identified by linear regression models in patients with T1D

To identify predictors of NO in whole blood, NO2-+NO3- in serum and urine in patients with T1D, three regression models adjusted for age, sex, diabetes duration, blood pressure, BMI, smoking, HbA1c, serum lipids, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, eGFR and nephropathy status were used. After application of a stepwise selection model based on AIC for a model with NO as a dependent variable, significant predictors remaining in the model were diabetes duration, sex, albuminuria and diabetic nephropathy. For NO2-+NO3- in serum, significant predictors were only HbA1c and eGFR. For NO2-+NO3- in urine, significant predictors were sex, BMI, albuminuria and eGFR (Table IV).

Table IV.

Associations between concentrations of NO in whole blood, NO2-+NO3- in serum and urine and clinical characteristics.

| Dependent variables | Predictors | B (95% CI) | P-value | R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO in whole blood, ng/g | Intercept | 25.951 (23.938, 27.964) | <0.001 | 0.134 |

| Diabetes duration, years | -0.101 (-0.192, -0.01) | 0.032 | ||

| Sex, male/female | 2.962 (0.91, 5.014) | 0.005 | ||

| Albumin/creatinine in urine, mg/mmol | -0.029 (-0.048, -0.01) | 0.003 | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy, yes/no | 10.241 (5.271, 15.212) | <0.001 | ||

| NO2-+NO3- in serum, µM | Intercept | 34.561 (11.73, 57.392) | 0.003 | 0.028 |

| HbA1c, % | 1.844 (-0.045, 3.733) | 0.057 | ||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 cm2 | -0.158 (-0.327, 0.011) | 0.069 | ||

| NO2-+NO3- in urine, µM | Intercept | 1285.682 (158.895, 2412.469) | 0.026 | 0.106 |

| Sex, male/female | -329.72 (-552.273, -107.166) | 0.004 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | -27.377 (-55.448, 0.694) | 0.057 | ||

| Albumin/creatinine in urine, mg/mmol | -1.707 (-3.345, -0.069) | 0.042 | ||

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 cm2 | 4.886 (-1.019, 10.792) | 0.106 |

Linear regression models for NO in whole blood, NO2/NO3 in serum and urine as dependent variables. Data are presented as B (95% CI). Analysis was performed only for data of patients with type 1 diabetes (N=268). Only predictors selected after application of AIC stepwise model are indicated. Initial models were adjusted for age, sex, diabetes duration, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, smoking, HbA1c, lipids, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, eGFR, diabetic nephropathy status. eGFR, ml/min, 1.72 cm2 and diabetic nephropathy, macroalbuminuria and eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NO, nitric oxide; NO2, nitrite; NO3, nitrate.

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the impact of T1D and diabetic nephropathy on the concentrations of NO in whole blood, and its metabolites NO2-+NO3- in serum and urine in patients with T1D.

In the present study, it was demonstrated that T1D resulted in increased NO production in whole blood and decreased NO2-+NO3- concentration in the serum. However, when T1D is complicated by diabetic kidney disease, urine excretion of NO2-+NO3- is decreased, which results in serum NO2-+NO3- not differing from the levels of healthy controls.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to measure NO concentration in whole blood measured by EPR in T1D patients. As in human tissues one can measure NO in ex vivo specimens only; in the present study, blood specimens were collected and incubated with a spin trap for 30 min. Therefore, the measured NO should have been produced by blood cells during the incubation or released from transporting molecules. Indeed, the ability to produce NO was reported for several types of blood cells. Previously, increased NO production in aged erythrocytes of patients with type 2 diabetes was reported (26). Increased NO production in whole blood of T1D patients in the present study could result from several processes. Besides being a NO depot due to the formation of NO and haemoglobin complexes, erythrocytes can produce NO, as they contain endothelial NO synthase (27). White blood cells and platelets produce NO via NO synthases (28-31) or independently of NO synthases (32). Finally, a nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-independent NO production from NO2-+NO3- is possible, especially in conditions characterised by endothelial dysfunction, low systemic pH and hypoxia, such as diabetes (10). Despite the fact that the present study could not demonstrate higher whole blood NO in patients with diabetic nephropathy, regression analysis indicated positive association between whole blood NO and diabetic nephropathy status. Therefore, the present results could be the first indication of increased NO production in blood cells of T1D patients.

In contrast to data on NO in the whole blood, lower serum NO2-+NO3- concentration were observed in patients with T1D and no diabetic nephropathy, compared with control subjects. Considering the above-mentioned increase of NO production by blood cells, this result underlines the differences of NO metabolism in different tissues. Indeed, in blood serum total NO2-+NO3- was measured, which consists of metabolites of NO produced by endothelium, blood cells and other tissues. To evaluate the contribution of the measured whole blood NO concentration in the present study (~25 ng/g) to blood serum NO2-+NO3-, this was recalculated in micromoles: It gives <1 µM in 30 min, which should be insignificant, as the measured serum NO2-+NO3- concentrations in the present study were on average >25 µM. To support the lack of direct association between blood NO and serum NO2-+NO3-, no correlation was found between these markers. Therefore, it can be can concluded that T1D leads to a decrease in serum NO2-+NO3- concentration and these changes are not dependent on NO production by blood cells. This decrease might be explained by decreased NO bioavailability due to diabetes-induced oxidative stress, when NO is scavenged by reactive oxygen species and ONOO- is formed (4,33). Data similar to the current findings have been reported in T1D (14) and type 2 diabetes (34). However, there are studies which report no differences in serum NO2-+NO3- concentrations in T2D patients compared with control subjects (35) and increased serum NO2-+NO3- in early T1D (16,36).

Although one would expect that in patients with T1D and diabetic nephropathy the concentration of serum NO2-+NO3- should decrease even further, in the present study, it did not differ from the levels observed in the control group. The reason for this observation might be the decreased eGFR in diabetic nephropathy group and thus some accumulation of serum NO2-+NO3-. Indeed, although serum and urine NO2-+NO3- demonstrated medium positive correlation in healthy subjects and patients with diabetes and no nephropathy, this correlation was not observed in patients with nephropathy. Moreover, regression analysis indicated that in patients with T1D, an increase in serum NO2-+NO3- is expected when eGFR decreases. Therefore, it is hypothesized that this accumulation of NO2-+NO3- in circulation might become a source of the NOS-independent NO synthesis (9,10) and consequent nitrosative stress that has been observed in diabetes (37). Thus, the authors hypothesized that the idea of inorganic nitrate/nitrite supplementation as a tool for prevention and treatment of complications of diabetes and atherosclerosis is controversial (4,10,17,18,38,39). Indeed, other researchers have also reported increased serum NO2-+NO3- in diabetic complications (15,34,35,40).

To supplement the present data on NO2-+NO3- in serum, decreased urine NO2-+NO3- concentrations were reported in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Moreover, albuminuria was a significant negative predictor of urine NO2-+NO3- in regression analysis. Decreased urine NO2-+NO3- excretion in diabetic nephropathy might be the consequence of deregulated NO synthesis in the microvasculature of kidney in diabetes due to altered expression of NOS isoforms (6,8). It can also result from a decrease in kidney function characteristic for diabetic nephropathy and leading to accumulation of NO metabolites in the blood, as discussed above. Indeed, a positive correlation was observed between urine NO2-+NO3- and eGFR in patients with T1D and healthy subjects, in agreement with the data of other studies (14,15,41).

The present study has some limitations. Major concerns are: The cross-sectional design of the study and the low number of patients with diabetic nephropathy. Subjects in the control group differ from T1D patients in age; all other differences between the groups are associated with diabetes and diabetic nephropathy.

The advantages of this study include previously unpublished data on NO in whole blood measured by EPR spectroscopy, a relatively large population of patients with T1D included and analysis of different markers of NO metabolism in patients with T1D and diabetic nephropathy.

To conclude, whole blood NO, serum and urine NO2-+NO3- are affected differently by T1D and diabetic nephropathy. Uncomplicated T1D is characterised by increased whole blood NO and decreased serum NO2-+NO3-. In diabetic kidney disease, urine excretion of NO2-+NO3- is decreased, which results in serum NO2-+NO3- not differing from the levels of healthy controls. Thus, kidney function is associated with NO metabolism in T1D. Studies with larger number of T1D patients with diabetic nephropathy are needed for an improved understanding of derangements of NO metabolism in diabetic kidney disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors of the present study would like to thank Mrs. Sanita Kalva-Vaivode and Mrs. Mārīte Cirse for patient recruitment, Dr Rihards Mallons, Dr Zane Dzērve and Dr Sabīne Skrebinska for their assistance with data management and Dr Carol Forsblom from the FinnDiane group for her valuable comments concerning presentation of data. LatDiane acknowledges all physicians involved in the recruitment of patients.

Funding

The present study was supported by the State Genome database project, Latvian Association of Endocrinology, a project of the University of Latvia: ‘Research of biomarkers and natural substances for acute and chronic diseases’ diagnostics and personalised treatment’.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JS designed the clinical set up of the study and wrote the manuscript. LB performed all measurements of nitric oxide by EPR method. KD performed all measurements of nitrite and nitrite. AD organized the logistics of the study. LP and JV did the statistical analysis. VR was responsible for biobanking. VP contributed to interpretation of the results and edited the manuscript. NS designed the study as well as wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is in line with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and received the Latvian Central Ethics Committee approval Nr.01-29.1/3. All subjects gave their written informed consent to participate.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD) Diabetologia. 2018;61:2461–2498. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellamea BS, Leitão CB, Friedman R, Canani LH. Nitric oxide system and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6(17) doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamagishi S, Matsui T. Nitric oxide, a janus-faced therapeutic target for diabetic microangiopathy-Friend or foe? Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pacher P, Beckman J, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tessari P. Nitric oxide in the normal kidney and in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2015;28:257–268. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ošiņa K, Rostoka E, Sokolovska J, Paramonova N, Bisenieks E, Duburs G, Sjakste N, Sjakste T. 1,4-Dihydropyridine derivatives without Ca2+-antagonist activity up-regulate Psma6 mRNA expression in kidneys of intact and diabetic rats. Cell Biochem Funct. 2016;34:3–6. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonova E, Sokolovska J, Boucher JL, Isajevs S, Rostoka E, Baumane L, Sjakste T, Sjakste N. New 1,4-Dihydropyridines down-regulate nitric oxide in animals with streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus and protect deoxyribonucleic acid against peroxynitrite action. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;119:19–31. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweier JL, Talukder MA. The role of oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alef MJ, Tzeng E, Zuckerbraun BS. Nitric oxide and nitrite-based therapeutic opportunities in intimal hyperplasia. Nitric Oxide. 2012;26:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JY, Ye ZX, Wang XF, Chang J, Yang MW, Zhong HH, Hong FF, Yang SL. Nitric oxide bioavailability dysfunction involves in atherosclerosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;97:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceriello A, Testa R. Antioxidant anti-inflammatory treatment in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32 (Suppl 2):S232–S236. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tessari P, Cecchet D, Cosma A, Vettore M, Coracina A, Millioni R, Iori E, Puricelli L, Avogaro A, Vedovato M. Nitric oxide synthesis is reduced in subjects with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59:2152–2159. doi: 10.2337/db09-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherney DZ, Reich HN, Jiang S, Har R, Nasrallah R, Hébert RL, Lai V, Scholey JW, Sochett EB. Hyperfiltration and effect of nitric oxide inhibition on renal and endothelial function in humans with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R710–R718. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00286.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarelli F, Cipollone F, Romano F, Tumini S, Costantini F, di Ricco L, Pomilio M, Pierdomenico SD, Marini M, Cuccurullo F, Mezzetti A. Increased circulating nitric oxide in young patinets with type 1 diabetes and persistent microalbuminuria: Relation to glomerular hyperfiltration. Diabetes. 2000;49:1258–1263. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savino A, Pelliccia P, Schiavone C, Primavera A, Tumini S, Mohn A, Chiarelli F. Serum and urinary nitrites and nitrates and doppler sonography in children with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2676–2681. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L, Hu L, Feng X, Wang S. Nitrate and nitrite in health and disease. Aging Dis. 2018;9:938–945. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahadoran Z, Ghasemi A, Mirmiran P, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. Beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in type 2 diabetes and its complications. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2015;12(16) doi: 10.1186/s12986-015-0013-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanin AF. Dinitrosyl iron complexes and S-nitrosothiols are two possible forms for stabilization and transport of nitric oxide in biological systems. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1998;63:782–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X. Real time and in vivo monitoring of nitric oxide by electrocehmical sensors-from dream to reality. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3434–3446. doi: 10.2741/1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Zhang X, Broderick M, Fein H. Measurement of nitric oxide production in biological systems by using griess reaction assay. Sensors. 2003;3:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39 (Suppl 1): S1-S266, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borisovs V, Ļeonova E, Baumane L, Kalniņa J, Mjagkova N, Sjakste N. Blood levels of nitric oxide and DNA breaks assayed in whole blood and isolated peripheral blood mononucleated cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mutat Res. 2018;843:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Core Team (2012) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL. http://www.R.project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bizjak DA, Brinkmann C, Bloch W, Grau M. Increase in red blood cell-nitric oxide synthase dependent nitric oxide production during red blood cell aging in health and disease: A study on age dependent changes of rheologic and enzymatic properties in red blood cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(e0125206) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cortese-Krott MM, Kelm M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in red blood cells: Key to a new erythrocrine function? Redox Biol. 2014;2:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Bonilla L, Moore JM, Racchumi G, Zhou P, Butler JM, Iadecola C, Anrather J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in neutrophils and endothelium contributes to ischemic brain injury in mice. J Immunol. 2014;193:2531–2537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gambaryan S, Tsikas D. A review and discussion of platelet nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthase: Do blood platelets produce nitric oxide from l-arginine or nitrite? Amino Acids. 2015;7:1779–1793. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-1986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saluja R, Saini R, Mitra K, Bajpai VK, Dikshit M. Ultrastructural immunogold localization of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in rat and human eosinophils. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;340:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide synthase in innate and adaptive immunity: An update. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:161–178. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tse WY, Williams J, Pall A, Wilkes M, Savage CO, Adu D. Antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-induced neutrophil nitric oxide production is nitric oxide synthase independent. Kidney Int. 2001;59:593–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10:4–18. doi: 10.2174/157016112798829760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyata S, Noda A, Hara Y, Ueyama J, Kitaichi K, Kondo T, Koike Y. Nitric oxide plasma level as a barometer of endothelial dysfunction in factory workers. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2017;125:684–689. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-110054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doganay S, Evereklioglu C, Er H, Türköz Y, Sevinç A, Mehmet N, Savli H. Comparison of serum NO, TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, sIL-2R, IL-6 and IL-8 levels with grades of retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:163–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoeldtke RD, Bryner KD, Vandyke K. Oxidative stress and autonomic nerve function in early type 1 diabetes. Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10286-010-0084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceriello A. Nitrotyrosine: New findings as a marker of postprandial oxidative stress. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2002:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stepanova YI, Kolpakov IY, Zyhalo VM, Boyarsky VG. Correction of endothelial dysfunction in children-residents of radioactively contaminated areas by nitric oxide donator. Probl Radiac Med Radiobiol. 2016;21:336–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norouzirad R, González-Muniesa P, Ghasemi A. Hypoxia in obesity and diabetes: Potential therapeutic effects of hyperoxia and nitrate. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017(5350267) doi: 10.1155/2017/5350267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gumanova NG, Teplova NV, Ryabchenko AU, Denisov EN. Serum nitrate and nitrite levels in patients with hypertension and ischemic stroke depend on diet: A multicenter study. Clin Biochem. 2015;48:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider MP, Ott C, Schmidt S, Kistner I, Friedrich S, Schmieder RE. Poor glycemic control is related to increased nitric oxide activity within the renal circulation of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4071–4075. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.