Abstract

For the last 50 years we have known of a broad-spectrum agent tilorone dihydrochloride (Tilorone). This is a small-molecule orally bioavailable drug that was originally discovered in the USA and is currently used clinically as an antiviral in Russia and the Ukraine. Over the years there have been numerous clinical and non-clinical reports of its broad spectrum of antiviral activity. More recently we have identified additional promising antiviral activities against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, Chikungunya, Ebola and Marburg which highlights that this old drug may have other uses against new viruses. This may in turn inform the types of drugs that we need for virus outbreaks such as for the new coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Tilorone has been long neglected by the west in many respects but it deserves further reassessment in light of current and future needs for broad-spectrum antivirals.

Key Words: Antiviral, broad spectrum, interferon inducers, respiratory virus infections

Introduction

In the last 5 years there have been 2 major Ebola virus outbreaks in Africa (1), the Zika virus in Brazil (2) and currently we are in the midst of a novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (3,4) currently spreading globally from China at the time of writing. Some of these viruses have the ability to rapidly spread to additional countries from their original location and they all create massive financial impacts. The overall morbidity from these virus outbreaks generally pales in comparison to the more common viral infections, such as influenza (5), HIV (6), and HBV (7) which kill orders of magnitude more annually. Newer viruses however attract significant attention because of the lack of available treatments and the fear of the unknown. It also indicates the need for broader spectrum antivirals that can be used for any new or emerging virus affecting human health.

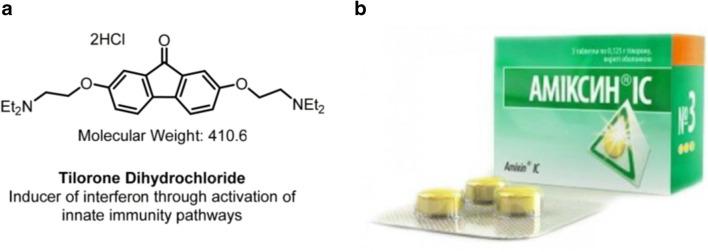

One such promising drug is tilorone dihydrochloride (Tilorone, 2,7-Bis[2-(diethylamino)ethoxy]-9H-fluoren-9-one) which is a small-molecule (410.549 Da) that is orally bioavailable (Fig. 1). The drug has typically been used in the dihydrochloride salt form and is yellow/orange in color. Tilorone was originally synthesized and developed at the pharmaceutical company Merrell Dow which is now part of Sanofi (8). The synthesis has been improved upon in recent years (9). Tilorone is currently used clinically as an antiviral in several countries outside the USA and is sold under the trade names Amixin® or Lavomax®. It is approved for use in Russia for several viral disease indications (influenza, acute respiratory viral infection, viral hepatitis, viral encephalitis, myelitis, and others), and is included in the list of vital and essential medicines of the Russian Federation (10). Tilorone is also registered for human use in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan as an antiviral and immunomodulating medication. In Russia, tilorone is also available over the counter in both adult and child (ages 7 and above) dosages. Tilorone has a track record of safe use in children and adults for ~20 years as both a prophylaxis and treatment for viral diseases. The drug has been produced and manufactured at the kiloton (1000 kg) scale and can be produced at a very low cost per dose based on the current list price (11).In vivo efficacy studies from the literature support possible uses of tilorone against a broad array of infections including influenza A, influenza B, herpes simplex virus 1, West Nile virus, Mengo virus, Semliki Forest virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, encephalomyocarditis virus (12–17) and more recently against human coronaviruses including MERS-CoV (18) (Table I). Human clinical studies outside the US evaluated tilorone as a treatment for Acute Respiratory Viral Infections (ARVIs), where it demonstrated significantly improved patient outcomes (22–25). The drug also showed 72% prophylactic efficacy in respiratory tract infections in humans (26). Tilorone has undergone several clinical trials published in Russian journals (23,25,27,28). Besides this track record of use in Russia and neighboring countries, tilorone has never been evaluated and tested for safety and efficacy under studies that meet current ICH and FDA guidelines and regulations, and previous nonclinical data (if any) are not readily available.

Fig. 1.

(a) Chemical Structure and Description of Tilorone Dihydrochloride. (b) Package of Tilorone (Trade Name Amixin® IC) in Tablet Format used in Russia.

Table I.

Literature data on Tilorone antiviral activity.

| Virus | Genus | Type | Efficacy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mengo virus | cardiovirus | + ssRNA | 80% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Semliki Forest | alphavirus | + ssRNA | 100% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Vesicular stomatitis | vesiculovirus | -ssRNA | 20% survival but delayed time to death with two 250 mg/kg doses | (12) |

| Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) | cardiovirus | + ssRNA | 80% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Influenza B | Betainfluenza virus | -ssRNA | 50% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Influenza A/Equine-1 | Alphainfluenza virus | -ssRNA | 40% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Influenza A/Jap/305 | Alphainfluenza virus | -ssRNA | 30% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg single oral dose | (12) |

| Herpes simplex virus 1 | simplexvirus | dsDNA | 45% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg oral doses for 7 days | (12) |

| West Nile virus | flavivirus | + ssRNA | 46% lethality protection at 10 mg/kg | (19) |

| MERS | Betacoronavirus | + ssRNA | EC50 10.56 μM, CC50 > 20 μM | (18) |

| VEEV | Alphavirus | + ssRNA | 1 log drop of virus titer at 25 mg/ml in vitro | (20) |

| EMCV | cardiovirus | + ssRNA | 1 log drop of virus titer at 25 mg/ml in vitro | (20) |

| VEEV | Alphavirus | + ssRNA | 100% survival in mice at 250 mg/kg | (21) |

Despite its history of use for viral diseases, its activity against EBOV was discovered using a machine-learning computational model trained on in vitro anti-Ebola screening data. The training data was generated through a large collaborative drug-repurposing program that identified multiple classes of Ebola inhibitors with in vitro and in vivo activities (29,30). This model predicted Ebola inhibitory activity for tilorone, which was then tested using an in vitro anti-Ebola assay for activity. Tilorone gave a 50% effective concentration (EC50) in this assay of 230 nM (Table II), making it one of the most potent small-molecule inhibitors of EBOV reported at the time (31,35,36). After a series of toxicity and pharmacokinetic studies, the compound was tested in a mouse model of EBOV infection where it was associated with 90-100% survival in a mouse EBOV efficacy study at three different doses. For comparison, the vehicle-treated group had only 10% survival (36). Interestingly, tilorone was either comparable or had significantly reduced survival rates as compared to the vehicle in guinea pigs infected with EBOV (33). These results led us to more broadly profile the antiviral spectrum of activity for Tilorone (Table II). Recent data suggests Tilorone can be used for Marburg (MARV) (33) as well Chikungunya virus (CHIK) and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Table II) making it a potential broad-spectrum class of antiviral therapeutic as it has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical animal disease models against very diverse viral families including, filovirus, hepadnavirus, human herpesvirus, orthomyxovirus, picornavirus, alphavirus, rhabdovirus, and flavivirus.

Table II.

Recent antiviral screening data for Tilorone generated under the NIAID-DMID NCEA antiviral in vitro screening services except where noted

| Virus | Strain | Genus | Type | Cell line | EC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBOV | Zaire | Filovirus | -ssRNA | HeLa | 0.23 | 6.2 | (31) |

| EBOV | Zaire | Filovirus | - ssRNA | Vero 76 | >11* | 11 | (32) |

| MARV | Musoke | Filovirus | - ssRNA | HeLa | 1.9 | – | (33) |

| Influenza A virus H1N1 | California/07/20/09 | Influenzavirus | - ssRNA | MDCK | >19 | 19 | |

| Tacaribe virus | TRVL 11573 | Arenavirus (new world) | −/+ ssRNA | Vero 76 | 29* | 32 | |

| CHIKV | S27 (VR-67) | Alphavirus | + ssRNA | Vero 76 | 4.2* | 32 | (34) |

| MERS-CoV | EMC | Betacoronavirus | + ssRNA | Vero 76 | 3.7* | 36 | (34) |

| Poliovirus 3 | WM-3 | Enterovirus | + ssRNA | Vero 76 | >25* | 25 | |

| VEEV | TC-83 | Alphavirus | + ssRNA | Vero 76 | 18* | 32 |

*In vitro antiviral data in Vero 76 cells may underestimate antiviral activity due to lacking IFN pathways

Mechanism

Tilorone was initially identified as an inducer of interferon after oral administration (37). The discovery of tilorone was followed by publications describing an ability to induce interferon (IFN) as a possible antiviral mechanism (12,37). Tilorone is water soluble, highly permeable, and is able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier (38) which suggests that it could access sites of the body where viruses might hide out.

To our surprise, the differences in anti-EBOV assays performed in HeLa cells and Vero 76 cells (Table II) initially indicated it may be due to the latter being IFN-deficient [24], unlike normal mammalian cells, and may not respond to tilorone in the same manner as HeLa cells. Given the reported activity of tilorone as an inducer of IFN, this differential antiviral activity data supported the hypothesis that the antiviral activity of tilorone is likely derived from its activation of host innate immunity pathways. Interestingly, the fact that in vitro antiviral activity is observed against MERS-CoV and CHIKV in Vero 76 cells suggests that these viruses are affected by different innate immunity pathways or tilorone has multiple targets that contribute to its overall antiviral activity.

In mice treated with tilorone after maEBOV challenge or in unchallenged animals numerous cytokines and chemokines increased significantly (32) unchallenged mice injected with tilorone vs vehicle and naïve groups showed significantly higher levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-17, Eotaxin, MCP-1, MIP-1B and RANTES. IL-10, IL-12 (p40), MCP-1, MIP-1B and RANTES. In multiple cases the unchallenged tilorone mice had a significantly higher response for many of the cytokines and chemokines as compared with the maEBOV-challenged group administered tilorone. This is the case for IL-2, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), Eotaxin and RANTES. Tilorone has also been shown to increase in vivo secretion of IL-6, TNF-a and IL-12 in macrophages from naïve BALB/c mice (39). While we have found no references referring explicitly to side effects of tilorone, the production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to drug treatment may exacerbate the clinical symptoms of some viral infections which result in cytokine storms such as influenza (40).

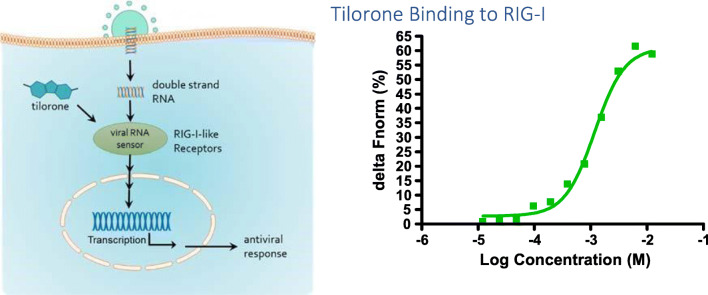

The antiviral efficacy of tilorone and the observation of its lack of in vitro anti-EBOV potency in IFN-deficient cell lines led us to hypothesize that the drug may work by activating specific innate immune system pathways that suppress viral replication. One candidate target is the RIG-like receptor (RLR) signaling pathway that can recognize intracellular viral RNA and induce a cellular response that leads to induction of IFNs (41) (Fig. 2). This exact mechanism is not yet proven, but several pieces of data support this hypothesis: Activation of RLR signaling pathways leads to IFN production (42), a well-known activity of tilorone. Tilorone causes a rapid increase in the mitochondrial potential (after 30 minutes), which may reflect the activity of the direct downstream signaling partner of RIG-I called the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) (43). The RLR signaling and the MAVS protein have been shown to be a critical mediator of viral replication in mice (44). In vitro binding data shows that tilorone can directly bind human RIG-I, though only weakly when the assay is performed in a simple buffer with no other cellular components (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(a) The Hypothesized Mechanism of Action for Tilorone is Activation of Innate Immunity Pathways such as the RIG-I-Like Receptor Pathway that Induces IFN and Activates a Cellular Antiviral Response. (b) Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) Binding Data of Tilorone to the Human Viral RNA Sensor RIG-I Shows a Low-Affinity (EC50 = 0.5 mM) in this Cell-Free in vitro Model.

Lysosomotropic mechanism

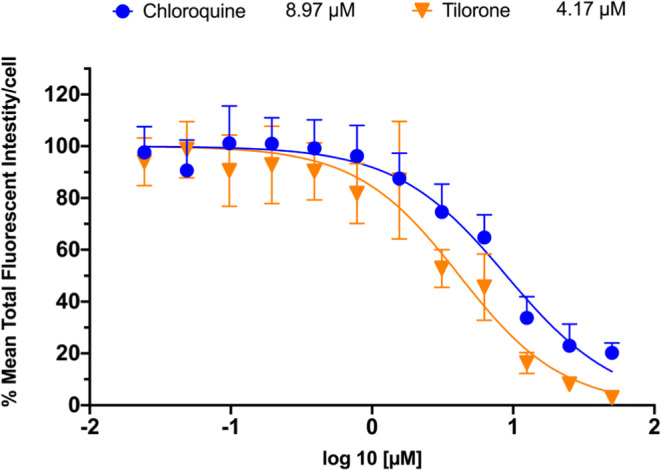

Lysosomotropic amines can diffuse freely and rapidly across the membranes of acidic cytoplasmic organelles in their unprotonated form, then when they enter the acidic environment they become protonated. This halts free diffusion out, causing substantial accumulation (45). The lysosomotropic amine concentration in the organelle increases such that the concentration of [H+] decreases. Tilorone, is an amphiphilic cationic compound which was shown to induce the storage of sulfated glycosaminoglycans in fibroblasts as well as enhanced the secretion of precursor forms of lysosomal enzymes (46). Tilorone was also found to increase lysosomal pH and inhibited the ATP-dependent acidification (46). We have also recently confirmed that tilorone is lysosomotropic, with an IC50 (~4 μM), on par with the well known lysosomotropic compound chloroquine (Fig. 3). Others have shown that the tilorone induced glycosaminoglycans storage can be separated from the tilorone induced secretion of lysosomal enzymes (47). The lysosomotropic mechanism may also have an important role as tilorone blocks viral entry. Cationic amphiphilic drugs have been proposed recently as a useful starting point for broad spectrum antivirals (48).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of total Fluorescent Intensity/Cell of Lysotracker Red in MCF7 Cells. Lysotracker Accumulation in Lysosomes is pH Dependent, therefore a Reduction in Signal from the Lysotracker Suggests a pH Increase in these Organelles. This is Proposed to be caused by Accumulation of the Charged Base of the Lysosomotropic Compound in the Lysosome, which in a Lower pH Environment becomes Neutralized and Trapped in the Organelle.

Species differences in metabolism

A recent species comparison of metabolism of tilorone demonstrated N-deethylation and mono-oxygenation was higher in guinea pig relative to both mouse and human (33). The species-liver microsome stability relationship increased in the order of guinea pig, non-human primate, mouse, followed by human (33). The differences in metabolic stability between species could also account for any differences in efficacy observed between the mouse and guinea pig models of EBOV treated with tilorone. Whereas we saw efficacy for mouse, this was not apparent for guinea pig and it may be due to the metabolic stability differences.

Summary

While there are many antiviral drugs for several individual viral diseases e.g. HIV, HBV, influenza etc., there are currently no broad-spectrum antivirals approved in the USA. In contrast, tilorone has been widely used outside the USA for several decades and recent data suggests efficacy in an animal model of EBOV infection (36) while additional in vitro activities from several groups support the use of this molecule as a broad-spectrum treatment of various viral infections. The preclinical data around this compound and all available data allows a candidate product profile to be generated (Table III). This document will serve as a guide for future development efforts. It is expected that some changes and additions will occur with additional data and any interactions with the FDA or other regulatory agencies, but our preliminary data characterizing the activities and properties of tilorone already support many of the target parameters needed to move this forward as a broad-spectrum antiviral. Several recent articles have focused on repurposing of other classes of drugs in order to identify novel broad spectrum antivirals (49–51) and a few of these were found to impact viral entry (51). In addition, there are other broad spectrum antiviral drugs approved in Russia or elsewhere which may also be worthy of further assessment globally such as arbidol (52), triazavirin (53), cycloferon (54) and Kagocel (55). Tilorone is already an antiviral drug which we have barely begun to exploit since its development 50 years ago and with recent discoveries it has revealed a little more on its potential antiviral mechanism and several additional activities. This compound is therefore ripe for more wide-spread testing against emerging viruses like coronaviruses that are impacting human health globally such as Covid-19.

Table III.

Candidate Product Profile (CPP) for Tilorone as a Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Therapeutic

| Product Description | Tilorone dihydrochloride for oral use in the form of a tablet. | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action (MOA) | Tilorone dihydrochloride is an inhibitor of viral replication in mammalian host cells through activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. One such pathway may be the RIG-I-signaling pathway responsible for the sensing of intracellular viral RNA and activation of a cellular antiviral response. A further role may be via its lysosomotropic activity which could impact viral entry. | |

| Antiviral Activity |

EBOV: viral replication EC50 = 230 nM; 100% survival at 30 mg/kg once daily intraperitoneal (IP) dosing in a mouse Ebola infection model (36) In vitro activities*: CHIK (EC50 = 4.2 μM), MERS-CoV (EC50 = 3.7 μM), VEEV (EC50 = 18 μM), ZIKV (EC50 = 5.2 μM). Literature activities: HBV and HCV, Herpes Simplex Virus, Influenza A and B virus, Mengo Virus, Semliki Forest Virus, Vesicular Stomatitus Virus, and West Nile Fever Virus (8). * In vitro antiviral potencies can vary greatly depending on the host cell types and the innate immunity genes expressed in the cell line. For example, Vero 76 cells lack interferon (IFN) pathways and generally show lower activities for Tilorone. |

|

| Pharmacology |

Human Pharmacology: After oral administration, it is rapidly absorbed from the digestive tract. Bioavailability is 60%. Binding to plasma proteins is ~80%. It is not subject to biotransformation. T1/2 = 48 h, and is excreted unchanged in feces (70%) and urine (9%). It does not accumulate (24) (11). Mouse Pharmacokinetics: At 10 mg/kg IP dosing: t1/2 = 19 h; Tmax = 0.25 h; Cmax = 113 ng/mL; AUClast = 806 h·ng/mL; Cl/F = 249,000 ml/h/kg; V/F = 8880 ml/kg. (36) In Vitro Drug Properties: Solubility: 470 μM in PBS pH 7.4; Permeability: high (Papp = 20 × 10−6 cm/s in CACO-2 assay); not a Pgp substrate; plasma protein binding: human = 52%, mouse = 61%; plasma stability (5 h): human = 95%, mouse = 95%; liver microsomal stability: mouse t1/2 = 48 min. (36) |

|

| Indications and Usage |

• Treatment of EBOV • Post-exposure Prophylaxis of EBOV • Treatment of acute infections from ZIKV, CHIK, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and/or influenza. |

|

| Primary Efficacy Endpoints | Target: 100% efficacy in EBOV animal studies with ≤10% survival among controls | Minimal: 60% efficacy in EBOV animal studies with ≤10% survival among controls |

| Secondary Efficacy Endpoints |

Target: Broad species coverage (Zaire and Sudan EBOV and Marburg virus; Bundibugyo EBOV) |

Minimal: Zaire and Sudan EBOV |

| Expected Safety Outcomes | Target: No serious adverse effects | Minimal: Acceptable therapeutic index to support treatment for lifethreatening |

|

Dosage and Administration |

Target: Efficacious when administered post-symptomatically; once daily dosing for up to 7 days | Minimal: Efficacious when administered post-exposure; twicedaily dosing for up to 7 days |

| Produce Stability and Storage |

Target: Shelf life of at least 24 months without refrigeration |

Minimal: Shelf life of at least 12 months without refrigeration |

| Patient Populations | Target: All age-groups and populations |

Minimal: All healthy adults, excluding pregnant and lactating women |

| Contraindications | Possible contraindications from Russian labeling: Hypersensitivity, pregnancy, breastfeeding, children under 7 years. | |

| Drug Interactions |

Compatible with antibiotics and other drugs for the treatment of viral and bacterial diseases. CYP450 Inhibition Screening: IC50 > 50 μM for 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4 (36) |

|

| How Supplied | Tablets supplied in a single dosage strength and packaged for maximal stability in high-humidity and warm temperature environments. | |

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

We kindly acknowledge NIH funding: R21TR001718 from NCATS and R44GM122196-02A1 from NIGMS (PI – Sean Ekins). Dr. Mindy Davis is gratefully acknowledged for assistance with the NIAID virus screening capabilities, Task Order number B22. Dr. Luke Mercer and Caleb Goodin (Cambrex) are acknowledged for their work on lysosome accumulation assays. Dr. Vadim Makarov is kindly acknowledged for discussions on Russian antivirals. SE is founder and owner of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. TRL is an employee of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. has an orphan designation on tilorone for use against Ebola and a provisional patent submitted for use for Marburg.

Abbreviations

- CHIKV

Chikungunya virus

- EBOV

Ebola virus

- EMCV

Encephalomyocarditis

- HBV

Hepatitis B Virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ICH

International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use

- IFN

Interferon

- MARV

Marburg virus

- MERS

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

- RIG-I

Retinoic acid-inducible gene I

- SARS

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

- VEEV

Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus;

Footnotes

The article was updated: Tables 1 and 2 had data in the bottom half (right hand side) of each table that was formatted incorrectly. The tables have been corrected.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/6/2020

The mentioned Tables below had data in the bottom half (right hand side) of each table that was formatted incorrectly in the final proof version versus the submitted version.

References

- 1.Furuyama W, Marzi A. Ebola virus: pathogenesis and countermeasure development. Annu Rev Virol. 2019;6(1):435–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musso D, Ko AI, Baud D. Zika virus infection - after the pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1444–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK, Washington State -nCo VCIT. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.CDC. Influenza (flu). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html.

- 6.CDC. AIDS and HIV. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/aids-hiv.htm.

- 7.CDC. Hepatitis B. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hepatitis.htm.

- 8.Fleming RW, Wenstrup DL, Andrews ER. Bis-basic ethers and thioethers of fluorenone,fluorenol and fluorene. In: US3592819A, editor.: Aventis Inc; 12/30/1968.

- 9.Zhang J, Yao Q, Liu Z. An effective synthesis method for Tilorone Dihydrochloride with obvious IFN-alpha inducing activity. Molecules. 2015;20(12):21458–21463. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selkova EP, Iakovlev VN, Semenenko TA, Filatov NN, Gotvianskaia TP, Danilina GA, Pantiukhova TN, Nikitina G, Tur'ianov M. [Evaluation of amyxin effect in prophylaxis of acute respiratory viral infections]. Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii, i immunobiologii. 2001(3):42–46. [PubMed]

- 11.Anon. Amixin. Available from: https://rupharma.com/amixin/.

- 12.Krueger RE, Mayer GD. Tilorone hydrochloride: an orally active antiviral agent. Science. 1970;169(3951):1213–1214. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3951.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz E, Margalith E, Winer B. The effect of tilorone hydrochloride on the growth of several animal viruses in tissue cultures. The Journal of general virology. 1976;31(1):125–129. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-31-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz E, Margalith E, Winer B. Inhibition of herpesvirus deoxyribonucleic acid and protein synthesis by tilorone hydrochloride. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9(1):189–195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.9.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veckenstedt A, Witkowski W, Hoffmann S. Comparison of antiviral properties in mice of bis-pyrrolidinoacetamido-fluorenone (MLU-B75), bis-dipropylaminoacetamido-fluorenone (MLU-B76), and tilorone hydrochloride. Acta Virol. 1979;23(2):153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loginova S, Koval'chuk AV, Borisevich SV, Syromiatnikova SI, Borisevich GV, Pashchenko Iu I, Khamitov RA, Maksimov VA, Shuster AM. Antiviral activity of an interferon inducer amixin in experimental West Nile fever. Vopr Virusol. 2004;49(2):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington DG, Lupton HW, Crabbs CL, Bolt LE, Cole FE, Jr., Hilmas DE. Adjuvant effects of tilorone hydrochloride (analog 11,567) with inactivated Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus vaccine. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, NY). 1981;166(2):257–262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shen L, Niu J, Wang C, Huang B, Wang W, Zhu N, Deng Y, Wang H, Ye F, Cen S, Tan W. High-Throughput Screening and Identification of Potent Broad-Spectrum Inhibitors of Coronaviruses. J Virol. 2019;93(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Vargin VV, Zschiesche W, Semenov BF. Effects of tilorone hydrochloride on experimental flavivirus infections in mice. Acta Virol. 1977;21(2):114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpov AV, Zholobak NM, Spivak NY, Rybalko SL, Antonenko SV, Krivokhatskaya LD. Virus-inhibitory effect of a yeast RNA-tilorone molecular complex in cell cultures. Acta Virol. 2001;45(3):181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuehne RW, Pannier WL, Stephen EL. Evaluation of various analogues of tilorone hydrochloride against Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11(1):92–97. doi: 10.1128/AAC.11.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman HE, Centifanto YM, Ellison ED, Brown DC. Tilorone hydrochloride: human toxicity and interferon stimulation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971;137(1):357–360. doi: 10.3181/00379727-137-35576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semenenko TA, Selkova EP, Nikitina GY, Gotvyanskaya TP, Yudina TI, Amaryan MP, Nosik NN, Turyanov MH. Immunomodulators in the prevention of acute respiratory viral infections. Russ J Immunol. 2002;7(2):105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selkova EP, Tur'ianov MC, Pantiukhova TN, Nikitina GI, Semenenko TA. Evaluation of amixine reactivity and efficacy for prophylaxis of acute respiratory tract infections. Antibiot Khimioter. 2001;46(10):14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sel'kova EP, Iakovlev VN, Semenenko TA, Filatov NN, Gotvianskaia TP, Danilina GA, Pantiukhova TN, Nikitina G, Tur'ianov M. [Evaluation of amyxin effect in prophylaxis of acute respiratory viral infections]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2001(3):42–46. [PubMed]

- 26.Sel'kova EP, Semenenko TA, Nosik NN, Iudina TI, Amarian MP, Lavrukhina LA, Pantiukhova TN, Tarasova G. [Effect of amyxin--a domestic analog of tilorone--on characteristics of interferon and immune status of man]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2001(4):31–35. [PubMed]

- 27.Chizhov NP, Smol'skaia TT, Baichenko PI, Luk'ianova RI, Teslenko VM, Bavra GP, Romanchenko IA, Shatalov EB, Ershov FI, Tazulakhova EB, et al. Clinical research on the tolerance for and the interferon-inducing activity of amiksin. Vopr Virusol. 1990;35(5):411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakirov IG. Use of amixin in the therapy and prevention of some viral infections. Klin Med (Mosk) 2002;80(12):54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madrid PB, Chopra S, Manger ID, Gilfillan L, Keepers TR, Shurtleff AC, Green CE, Iyer LV, Dilks HH, Davey RA, Kolokoltsov AA, Carrion R, Jr, Patterson JL, Bavari S, Panchal RG, Warren TK, Wells JB, Moos WH, Burke RL, Tanga MJ. A systematic screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of biological threat agents. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madrid PB, Panchal RG, Warren TK, Shurtleff AC, Endsley AN, Green CE, Kolokoltsov A, Davey R, Manger ID, Gilfillan L, Bavari S, Tanga MJ. Evaluation of Ebola virus inhibitors for drug repurposing. ACS Infect Dis. 2015;1(7):317–326. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekins S, Freundlich JS, Clark AM, Anantpadma M, Davey RA, Madrid P. Machine learning models identify molecules active against the Ebola virus in vitro. F1000Res. 2015;4:1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Lane TR, Massey C, Comer JE, Anantpadma M, Freundlich JS, Davey RA, Madrid PB, Ekins S. Repurposing the antimalarial pyronaridine tetraphosphate to protect against Ebola virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(11):e0007890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane TR, Massey C, Comer JE, Freiberg AN, Zhou H, Dyall J, Holbrook MR, Anantpadma M, Davey RA, Madrid PB, Ekins S. Efficacy of Oral Pyronaridine Tetraphosphate and Favipiravir Against Ebola Virus Infection in Guinea Pig Submitted. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Ekins S, Madrid PB. Tilorone: A broad-spectrum antiviral for emerging viruses. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother, In press. 2020 Preprint. 10.1101/2020.03.09.984856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Anantpadma M, Lane T, Zorn KM, Lingerfelt MA, Clark AM, Freundlich JS, Davey RA, Madrid PB, Ekins S. Ebola virus Bayesian machine learning models enable new in vitro leads. ACS Omega. 2019;4(1):2353–2361. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekins S, Lingerfelt MA, Comer JE, Freiberg AN, Mirsalis JC, O'Loughlin K, Harutyunyan A, McFarlane C, Green CE, Madrid PB. Efficacy of Tilorone Dihydrochloride against Ebola Virus Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Mayer GD, Krueger RF. Tilorone hydrochloride: mode of action. Science. 1970;169(3951):1214–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3951.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratan RR, Siddiq A, Aminova L, Langley B, McConoughey S, Karpisheva K, Lee HH, Carmichael T, Kornblum H, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Hoke A, Smirnova N, Rink C, Roy S, Sen C, Beattie MS, Hart RP, Grumet M, Sun D, Freeman RS, Semenza GL, Gazaryan I. Small molecule activation of adaptive gene expression: tilorone or its analogs are novel potent activators of hypoxia inducible factor-1 that provide prophylaxis against stroke and spinal cord injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:383–394. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaforio JJ, Ortega E, Algarra I, Serrano MJ. Alvarez de Cienfuegos G. NK cells mediate increase of phagocytic activity but not of proinflammatory cytokine (interleukin-6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-12) production elicited in splenic macrophages by tilorone treatment of mice during acute systemic candidiasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(6):1282–1294. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1282-1294.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Q, Zhou YH, Yang ZQ. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(1):3–10. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kell AM, Gale M, Jr. RIG-I in RNA virus recognition. Virology. 2015;479–480:110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zholobak NM, Kavok NS, Bogorad-Kobelska OS, Borovoy IA, Malyukina MY, Spivak MY. Effect of tilorone and its analogues on the change of mitochondrial potential of rat hepatocytes. Fiziolohichnyi zhurnal (Kiev, Ukraine : 1994). 2012;58(2):39–43. [PubMed]

- 44.Dutta M, Robertson SJ, Okumura A, Scott DP, Chang J, Weiss JM, Sturdevant GL, Feldmann F, Haddock E, Chiramel AI, Ponia SS, Dougherty JD, Katze MG, Rasmussen AL, Best SM. A systems approach reveals MAVS signaling in myeloid cells as critical for resistance to Ebola virus in murine models of infection. Cell Rep. 2017;18(3):816–829. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin RE, Marchetti RV, Cowan AI, Howitt SM, Broer S, Kirk K. Chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Science. 2009;325(5948):1680–1682. doi: 10.1126/science.1175667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta DK, Gieselmann V, Hasilik A, von Figura K. Tilorone acts as a lysosomotropic agent in fibroblasts. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1984;365(8):859–866. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1984.365.2.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lullmann-Rauch R, Pods R, Von Witzendorff B. Tilorone-induced lysosomal storage of sulphated glycosaminoglycans can be separated from tilorone-induced enhancement of lysosomal enzyme secretion. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49(9):1223–1233. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salata C, Calistri A, Parolin C, Baritussio A, Palu G. Antiviral activity of cationic amphiphilic drugs. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2017;15(5):483–492. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1305888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Serradilla M, Risco C, Pacheco B. Drug repurposing for new, efficient, broad spectrum antivirals. Virus Res. 2019;264:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersen PI, Krpina K, Ianevski A, Shtaida N, Jo E, Yang J, Koit S, Tenson T, Hukkanen V, Anthonsen MW, Bjoras M, Evander M, Windisch MP, Zusinaite E, Kainov DE. Novel Antiviral Activities of Obatoclax, Emetine, Niclosamide, Brequinar, and Homoharringtonine. Viruses. 2019;11(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Mazzon M, Ortega-Prieto AM, Imrie D, Luft C, Hess L, Czieso S, Grove J, Skelton JK, Farleigh L, Bugert JJ, Wright E, Temperton N, Angell R, Oxenford S, Jacobs M, Ketteler R, Dorner M, Marsh M. Identification of Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Compounds by Targeting Viral Entry. Viruses. 2019;11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Pecheur EI, Borisevich V, Halfmann P, Morrey JD, Smee DF, Prichard M, Mire CE, Kawaoka Y, Geisbert TW, Polyak SJ. The synthetic antiviral drug Arbidol inhibits globally prevalent pathogenic viruses. J Virol. 2016;90(6):3086–3092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02077-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karpenko I, Deev S, Kiselev O, Charushin V, Rusinov V, Ulomsky E, Deeva E, Yanvarev D, Ivanov A, Smirnova O, Kochetkov S, Chupakhin O, Kukhanova M. Antiviral properties, metabolism, and pharmacokinetics of a novel azolo-1,2,4-triazine-derived inhibitor of influenza a and B virus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(5):2017–2022. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01186-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kramer MJ, Cleeland R, Grunberg E. Antiviral activity of 10-carboxymethyl-9-acridanone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9(2):233–238. doi: 10.1128/AAC.9.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tazulakhova EB, Parshina OV, Guseva TS, Ershov FI. Russian experience in screening, analysis, and clinical application of novel interferon inducers. J Interf Cytokine Res. 2001;21(2):65–73. doi: 10.1089/107999001750069926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]