Abstract

Background

About 10% of women of reproductive age suffer from endometriosis. Endometriosis is a costly chronic disease that causes pelvic pain and subfertility. Laparoscopy, the gold standard diagnostic test for endometriosis, is expensive and carries surgical risks. Currently, no non‐invasive tests that can be used to accurately diagnose endometriosis are available in clinical practice. This is the first review of diagnostic test accuracy of imaging tests for endometriosis that uses Cochrane methods to provide an update on the rapidly expanding literature in this field.

Objectives

• To provide estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities for the diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis and deeply infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) versus surgical diagnosis as a reference standard.

• To describe performance of imaging tests for mapping of deep endometriotic lesions in the pelvis at specific anatomical sites.

Imaging tests were evaluated as replacement tests for diagnostic surgery and as triage tests that would assist decision making regarding diagnostic surgery for endometriosis.

Search methods

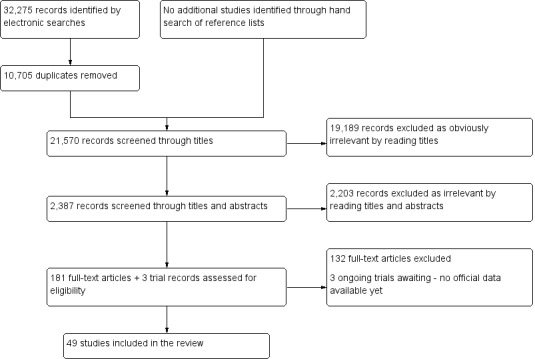

We searched the following databases to 20 April 2015: MEDLINE, CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, LILACS, OAIster, TRIP, ClinicalTrials.gov, MEDION, DARE, and PubMed. Searches were not restricted to a particular study design or language nor to specific publication dates. The search strategy incorporated words in the title, abstracts, text words across the record and medical subject headings (MeSH).

Selection criteria

We considered published peer‐reviewed cross‐sectional studies and randomised controlled trials of any size that included prospectively recruited women of reproductive age suspected of having one or more of the following target conditions: endometrioma, pelvic endometriosis, DIE or endometriotic lesions at specific intrapelvic anatomical locations. We included studies that compared the diagnostic test accuracy of one or more imaging modalities versus findings of surgical visualisation of endometriotic lesions.

Data collection and analysis

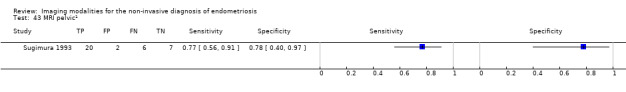

Two review authors independently collected and performed a quality assessment of data from each study. For each imaging test, data were classified as positive or negative for surgical detection of endometriosis, and sensitivity and specificity estimates were calculated. If two or more tests were evaluated in the same cohort, each was considered as a separate data set. We used the bivariate model to obtain pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity when sufficient data sets were available. Predetermined criteria for a clinically useful imaging test to replace diagnostic surgery included sensitivity ≥ 94% and specificity ≥ 79%. Criteria for triage tests were set at sensitivity ≥ 95% and specificity ≥ 50%, ruling out the diagnosis with a negative result (SnNout test ‐ if sensitivity is high, a negative test rules out pathology) or at sensitivity ≥ 50% with specificity ≥ 95%, ruling in the diagnosis with a positive result (SpPin test ‐ if specificity is high, a positive test rules in pathology).

Main results

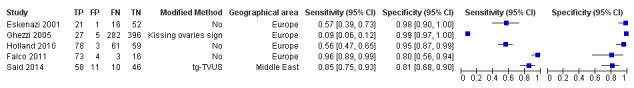

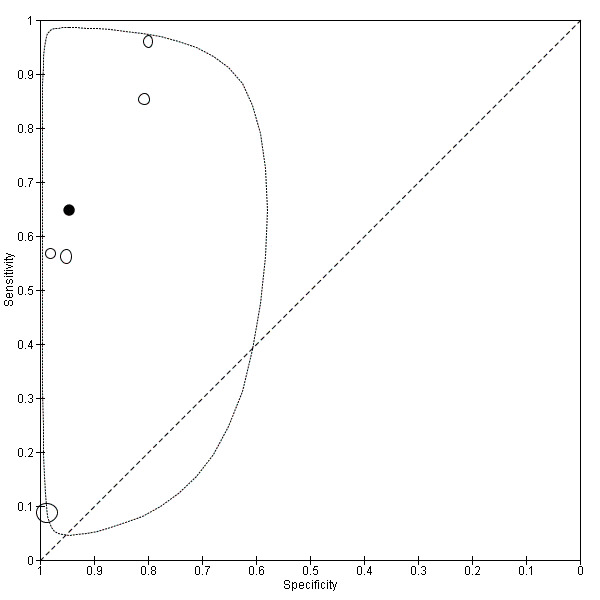

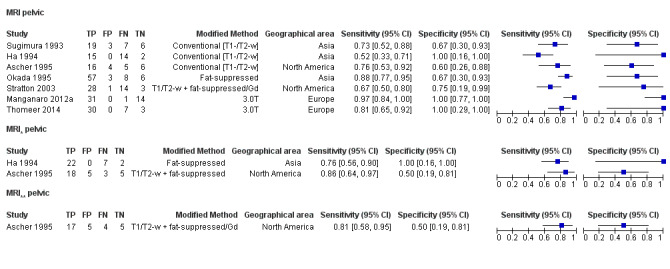

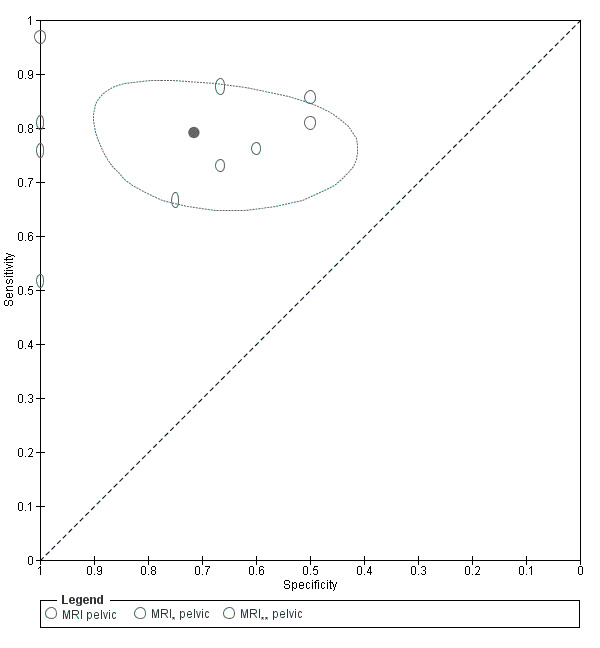

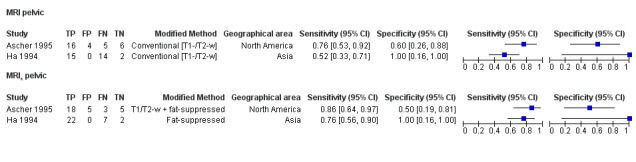

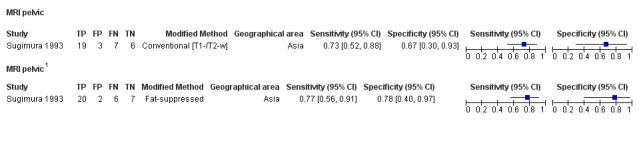

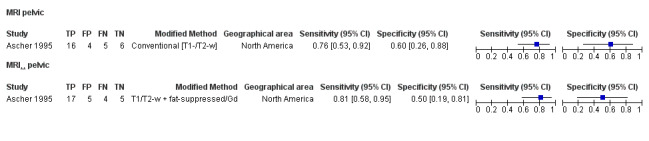

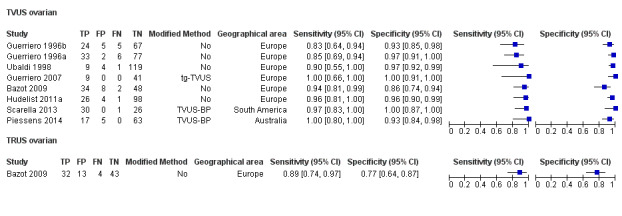

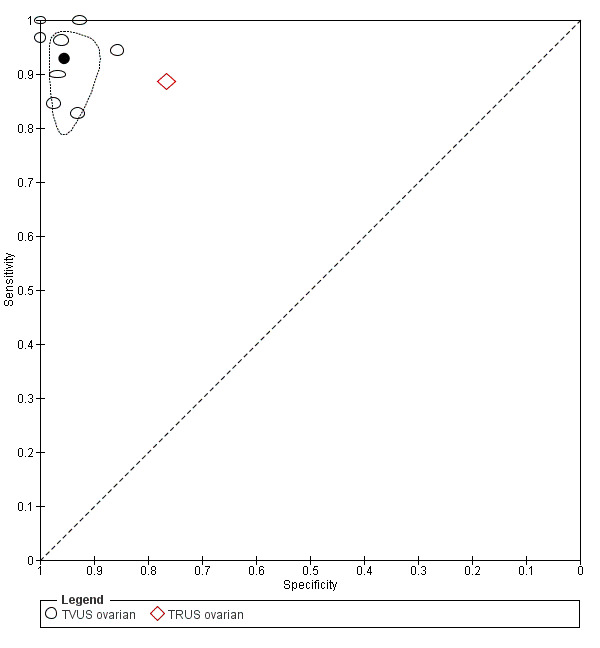

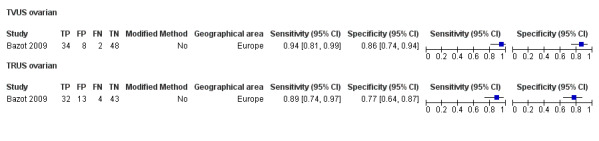

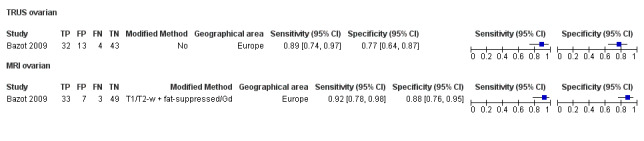

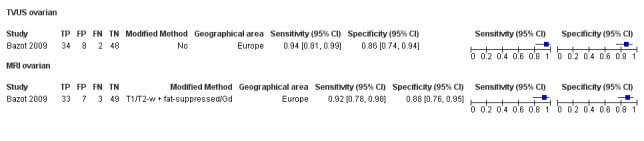

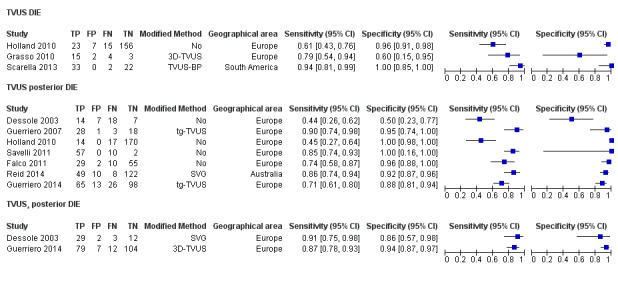

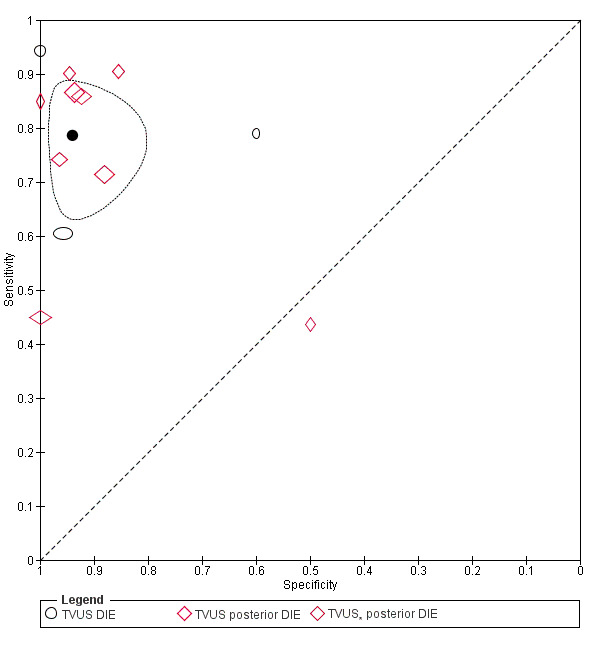

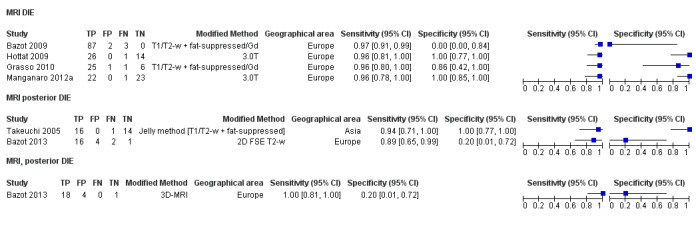

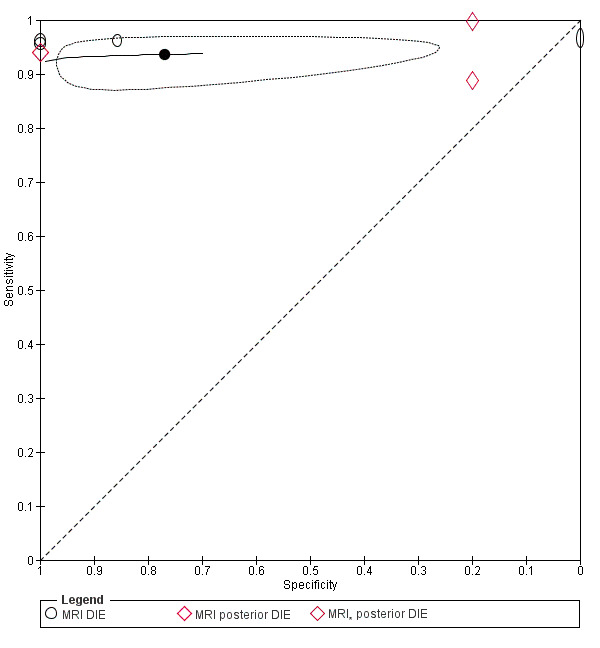

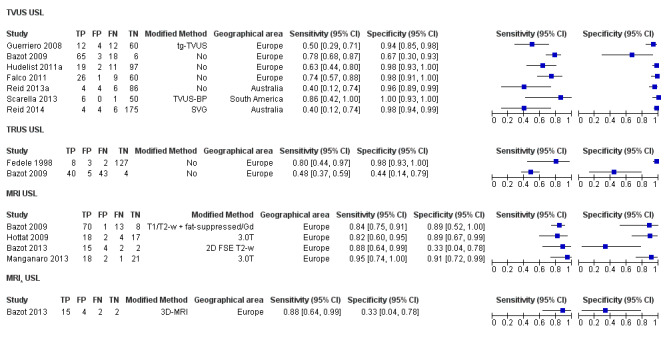

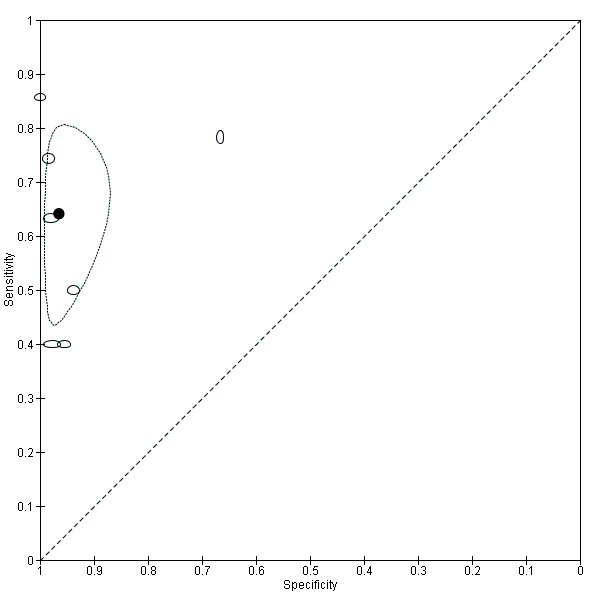

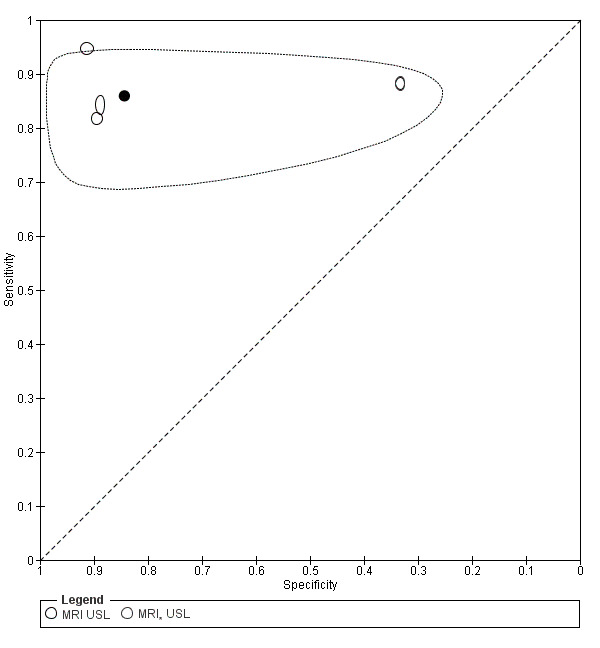

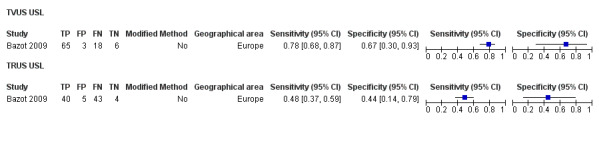

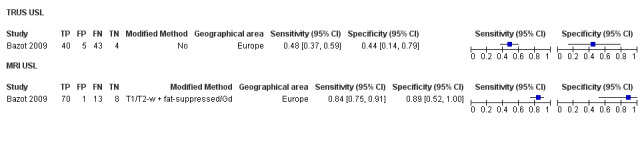

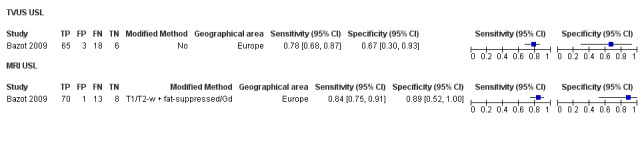

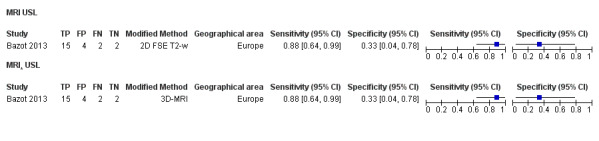

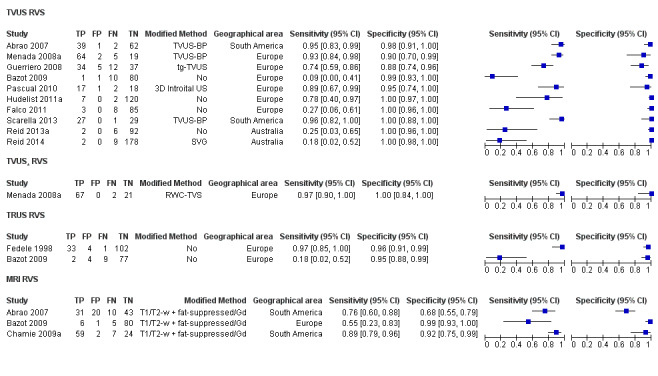

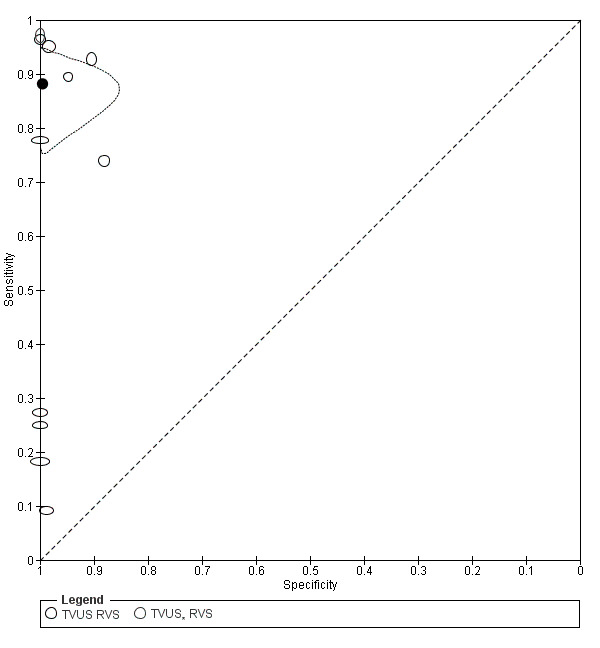

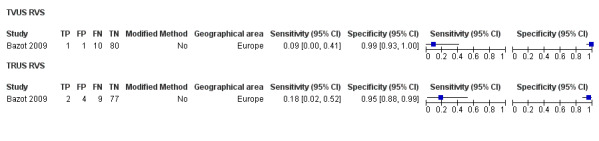

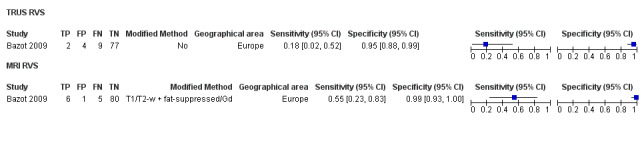

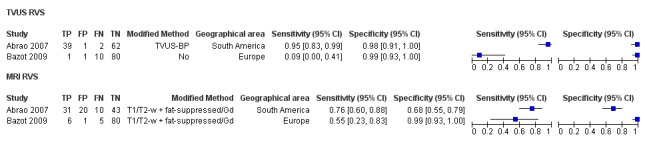

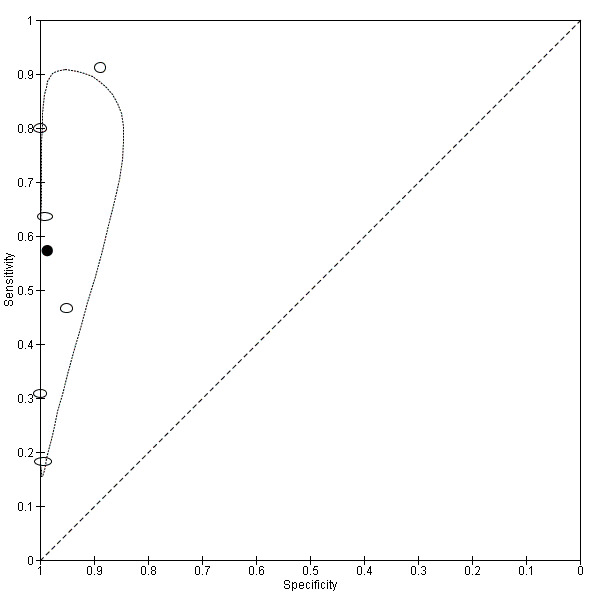

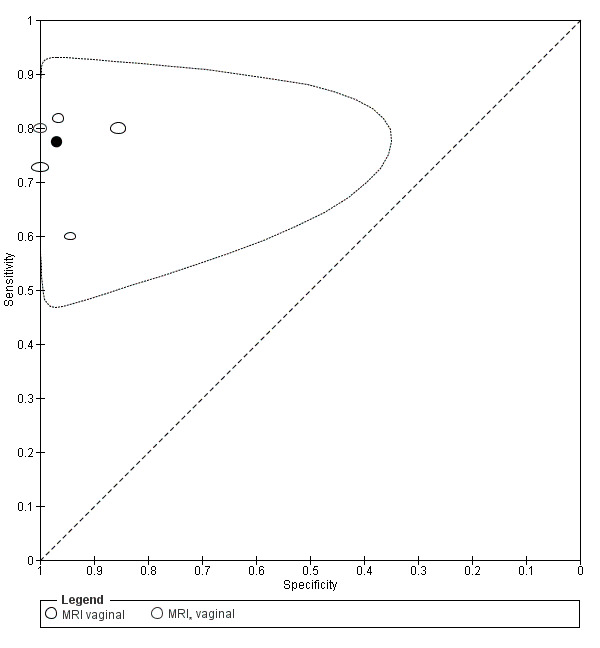

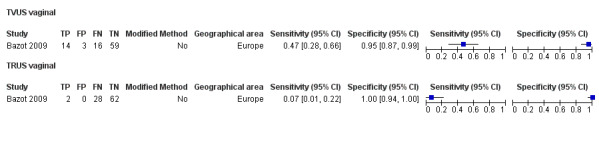

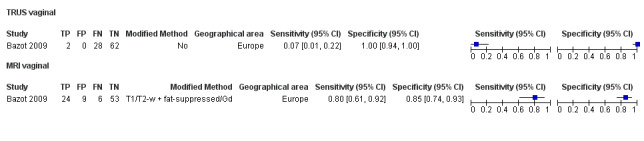

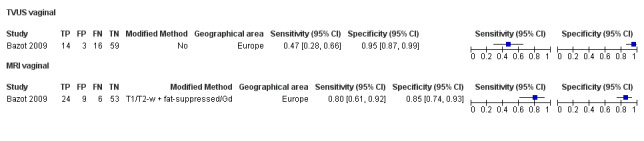

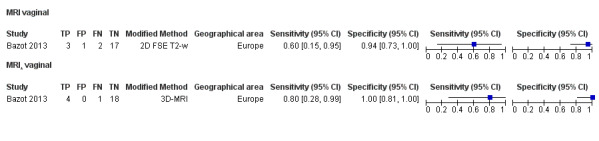

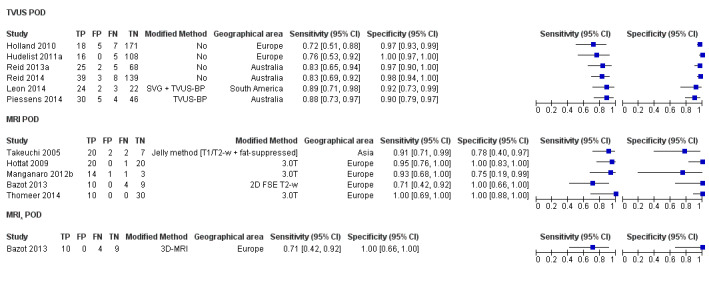

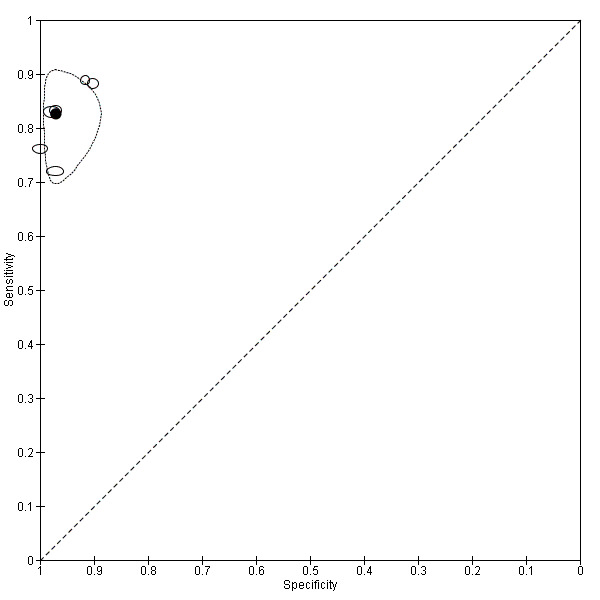

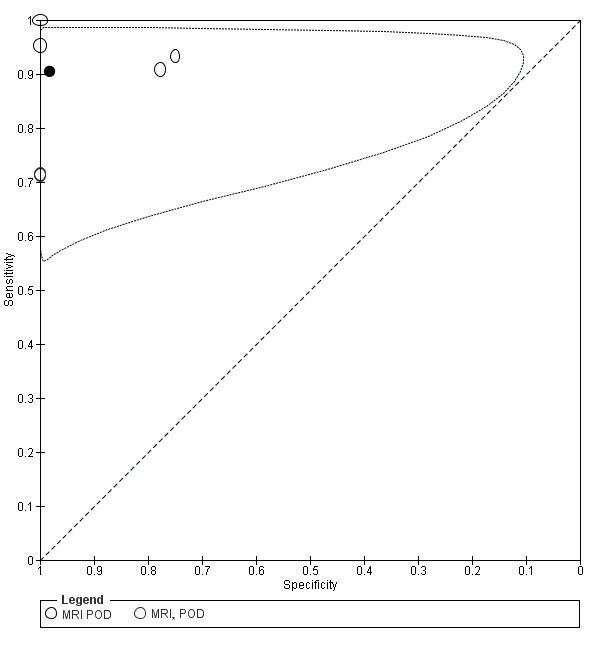

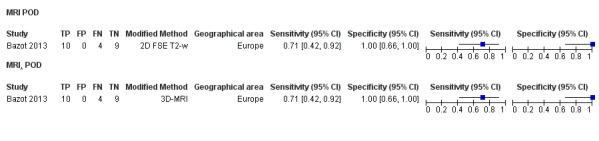

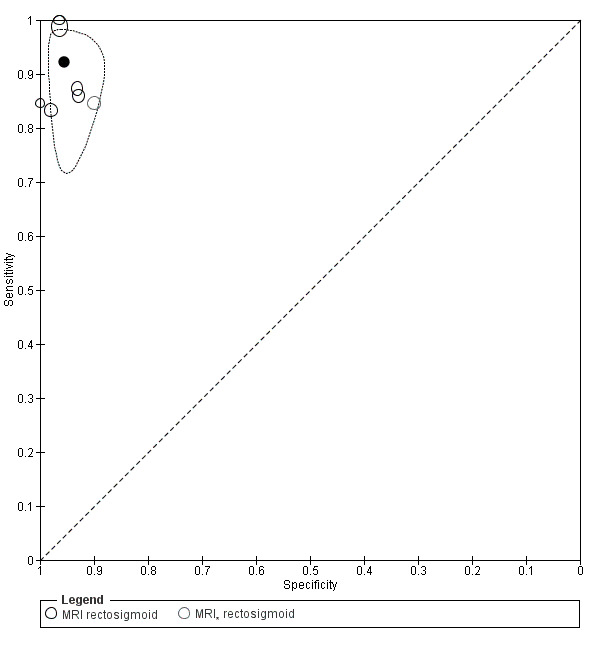

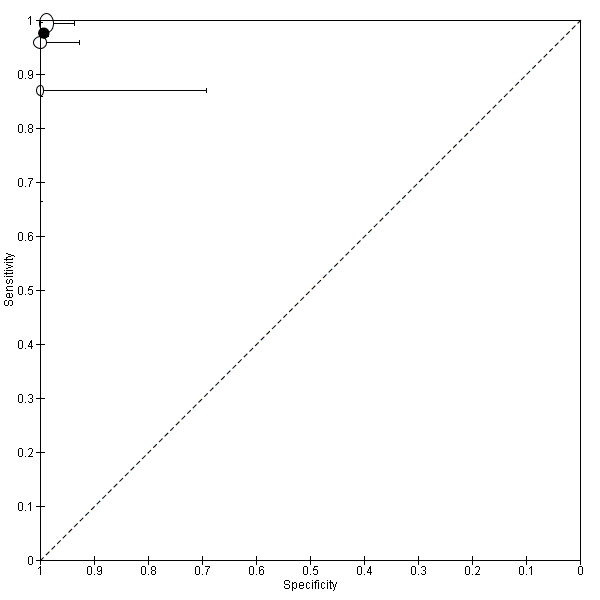

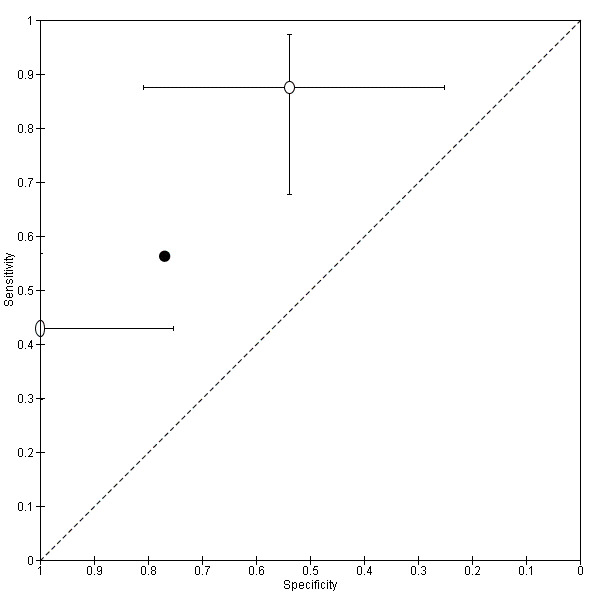

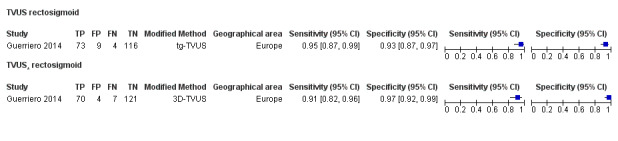

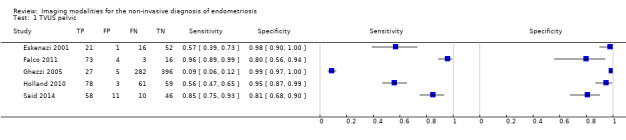

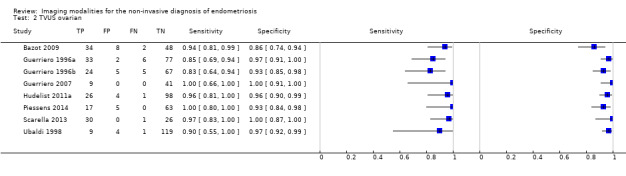

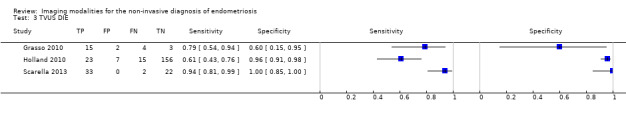

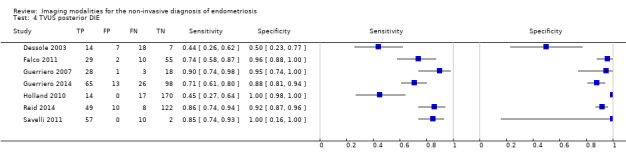

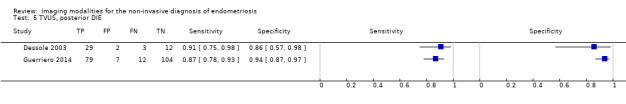

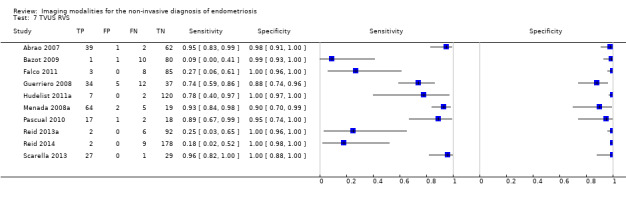

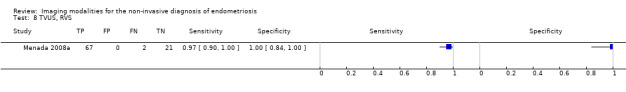

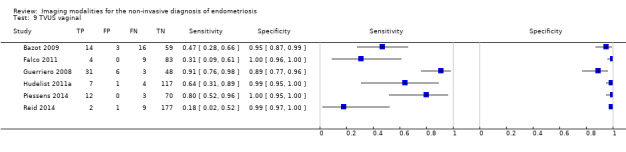

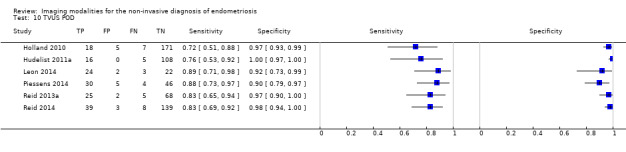

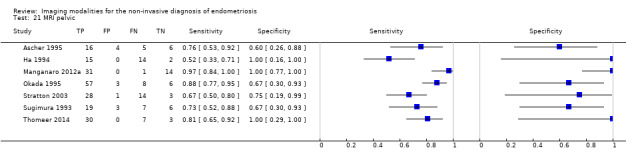

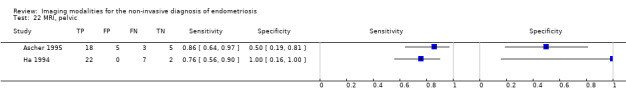

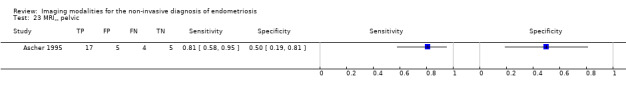

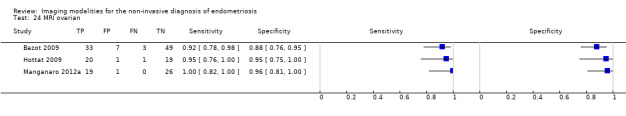

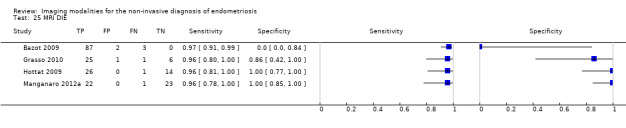

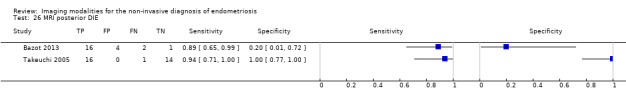

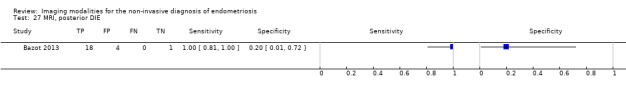

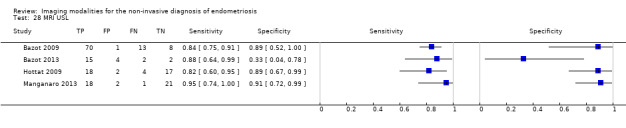

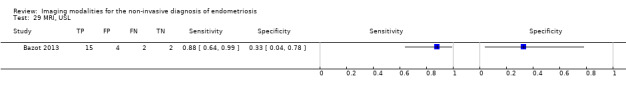

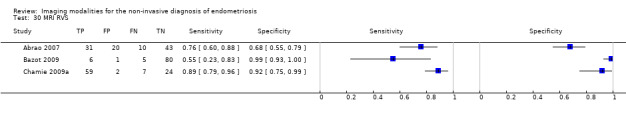

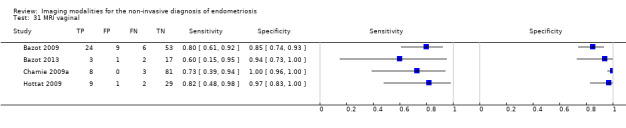

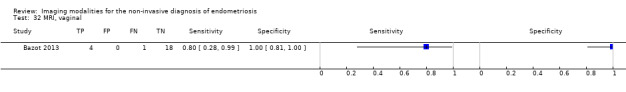

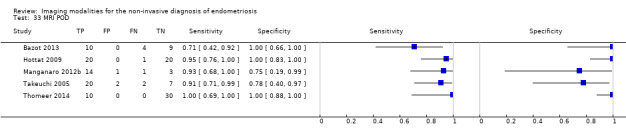

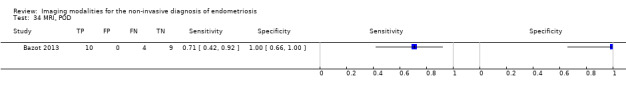

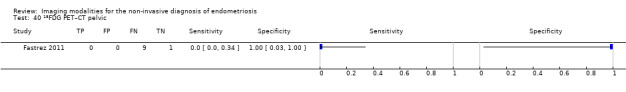

We included 49 studies involving 4807 women: 13 studies evaluated pelvic endometriosis, 10 endometriomas and 15 DIE, and 33 studies addressed endometriosis at specific anatomical sites. Most studies were of poor methodological quality. The most studied modalities were transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with outcome measures commonly demonstrating diversity in diagnostic estimates; however, sources of heterogeneity could not be reliably determined. No imaging test met the criteria for a replacement or triage test for detecting pelvic endometriosis, albeit TVUS approached the criteria for a SpPin triage test. For endometrioma, TVUS (eight studies, 765 participants; sensitivity 0.93 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87, 0.99), specificity 0.96 (95% CI 0.92, 0.99)) qualified as a SpPin triage test and approached the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test, whereas MRI (three studies, 179 participants; sensitivity 0.95 (95% CI 0.90, 1.00), specificity 0.91 (95% CI 0.86, 0.97)) met the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test and approached the criteria for a SpPin test. For DIE, TVUS (nine studies, 12 data sets, 934 participants; sensitivity 0.79 (95% CI 0.69, 0.89) and specificity 0.94 (95% CI 0.88, 1.00)) approached the criteria for a SpPin triage test, and MRI (six studies, seven data sets, 266 participants; sensitivity 0.94 (95% CI 0.90, 0.97), specificity 0.77 (95% CI 0.44, 1.00)) approached the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test. Other imaging tests assessed in small individual studies could not be statistically evaluated.

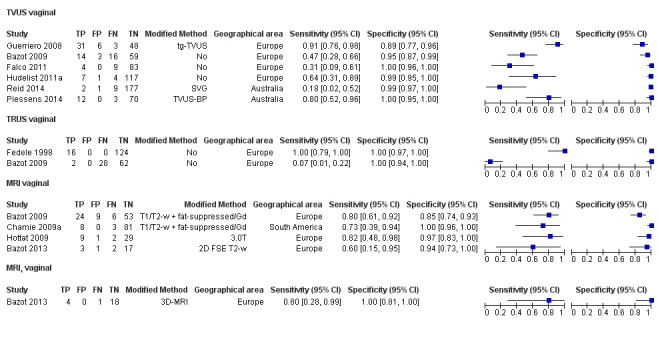

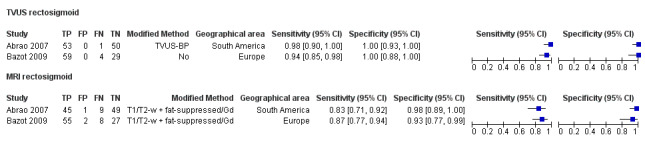

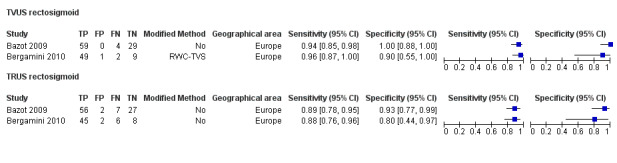

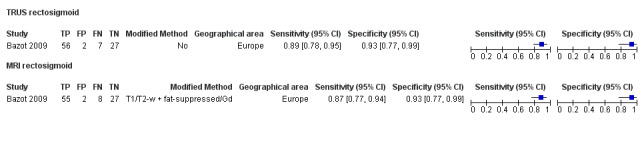

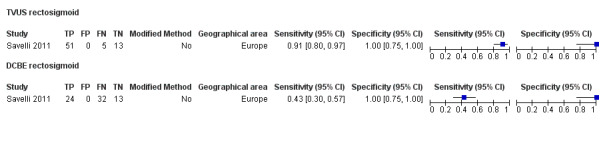

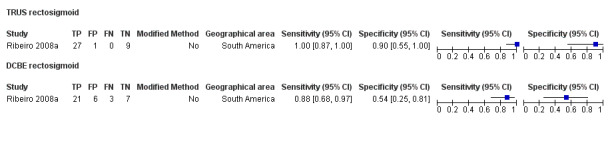

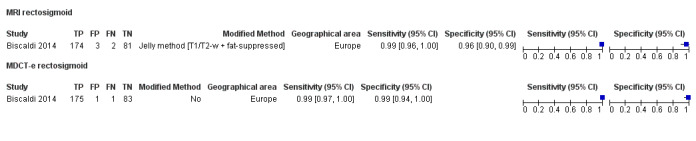

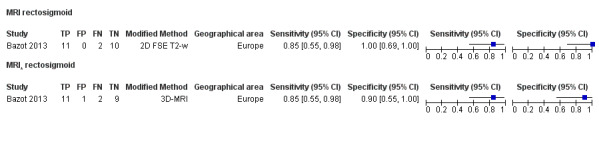

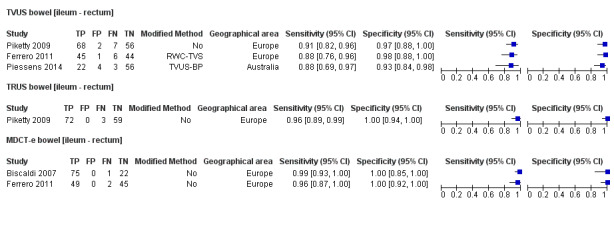

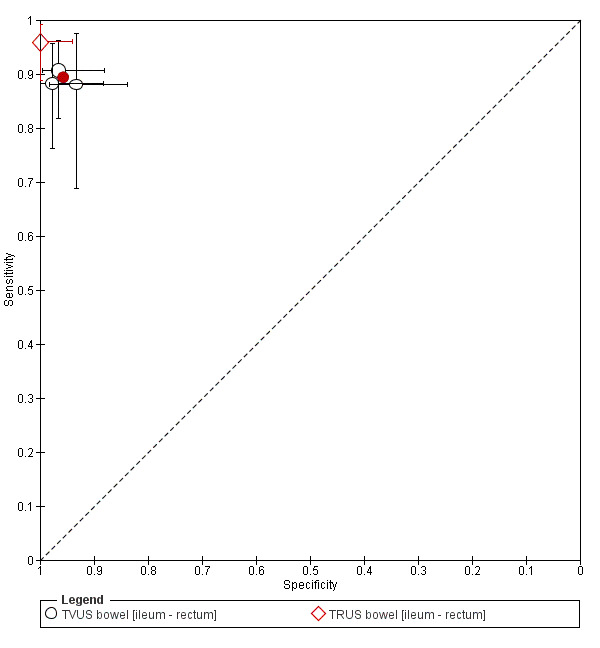

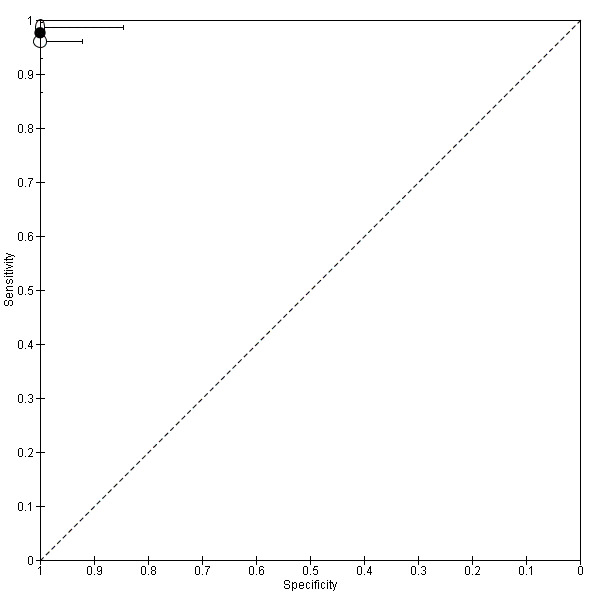

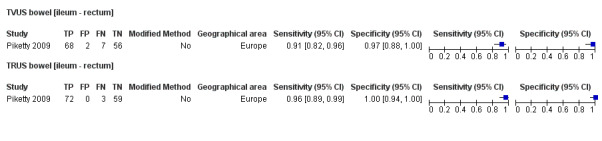

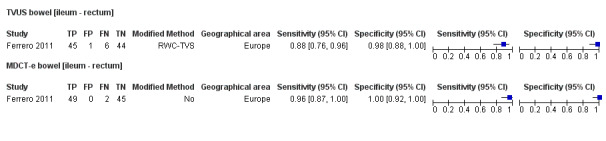

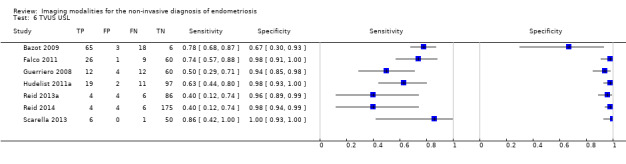

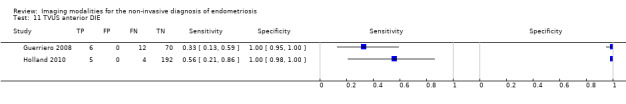

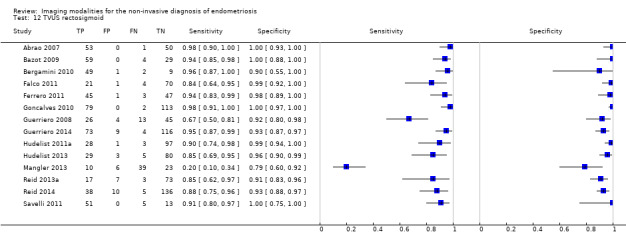

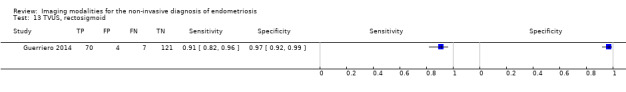

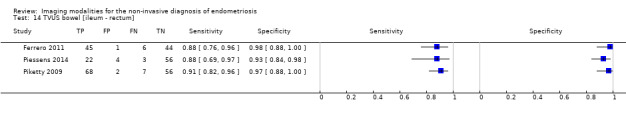

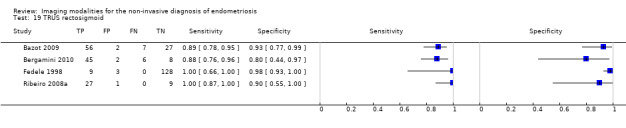

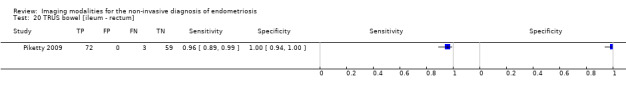

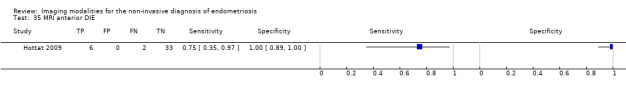

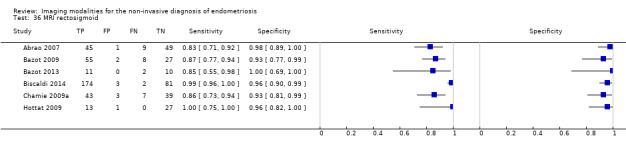

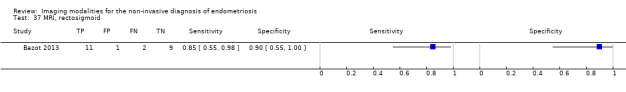

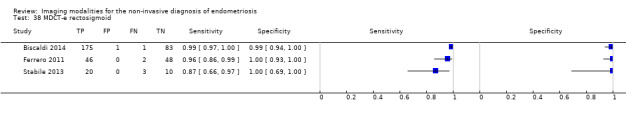

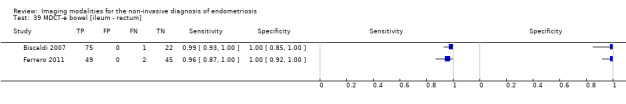

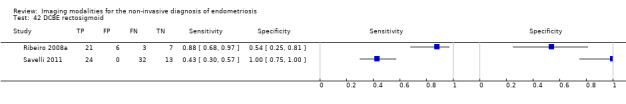

TVUS met the criteria for a SpPin triage test in mapping DIE to uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vaginal wall, pouch of Douglas (POD) and rectosigmoid. MRI met the criteria for a SpPin triage test for POD and vaginal and rectosigmoid endometriosis. Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) might qualify as a SpPin triage test for rectosigmoid involvement but could not be adequately assessed for other anatomical sites because heterogeneous data were scant. Multi‐detector computerised tomography enema (MDCT‐e) displayed the highest diagnostic performance for rectosigmoid and other bowel endometriosis and met the criteria for both SpPin and SnNout triage tests, but studies were too few to provide meaningful results.

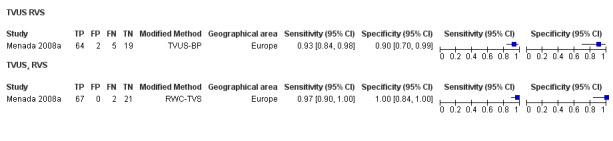

Diagnostic accuracies were higher for TVUS with bowel preparation (TVUS‐BP) and rectal water contrast (RWC‐TVS) and for 3.0TMRI than for conventional methods, although the paucity of studies precluded statistical evaluation.

Authors' conclusions

None of the evaluated imaging modalities were able to detect overall pelvic endometriosis with enough accuracy that they would be suggested to replace surgery. Specifically for endometrioma, TVUS qualified as a SpPin triage test. MRI displayed sufficient accuracy to suggest utility as a replacement test, but the data were too scant to permit meaningful conclusions. TVUS could be used clinically to identify additional anatomical sites of DIE compared with MRI, thus facilitating preoperative planning. Rectosigmoid endometriosis was the only site that could be accurately mapped by using TVUS, TRUS, MRI or MDCT‐e. Studies evaluating recent advances in imaging modalities such as TVUS‐BP, RWC‐TVS, 3.0TMRI and MDCT‐e were observed to have high diagnostic accuracies but were too few to allow prudent evaluation of their diagnostic role. In view of the low quality of most of the included studies, the findings of this review should be interpreted with caution. Future well‐designed diagnostic studies undertaken to compare imaging tests for diagnostic test accuracy and costs are recommended.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Chronic Disease, Cross‐Sectional Studies, Diagnostic Imaging, Diagnostic Imaging/methods, Endometriosis, Endometriosis/diagnosis, Endometriosis/pathology, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Ovarian Diseases, Ovarian Diseases/diagnosis, Ovarian Diseases/surgery, Pelvis, Positron‐Emission Tomography, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Sensitivity and Specificity, Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Imaging tests for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis

Review question

How accurate are imaging tests in detecting endometriosis? Can any imaging test be accurate enough to replace or reduce the need for surgery in the diagnosis of endometriosis?

Background

Women with endometriosis have endometrial tissue (the tissue that lines the womb and is shed during menstruation) growing outside the womb within the pelvis, causing chronic abdominal pain and difficulty conceiving. Currently, the only reliable way of diagnosing endometriosis is to perform laparoscopic surgery and visualise the endometrial deposits inside the abdomen. Because surgery is risky and expensive, imaging tests have been assessed for their ability to detect endometriosis non‐invasively. An accurate imaging test could lead to the diagnosis of endometriosis without the need for surgery, or it could reduce the need for surgery, so only women who were most likely to have endometriosis would require it. Furthermore, if imaging tests could accurately predict the location of endometriotic lesions, surgeons would have the information they need to plan and improve their surgical approach. Other non‐invasive ways of diagnosing endometriosis by using urine, blood and endometrial and combination tests have been evaluated in separate Cochrane reviews from this series.

Study characteristics

Evidence included in this review is current to April 2015. We included 49 studies involving 4807 participants. Thirteen studies evaluated pelvic endometriosis, 10 studies ovarian endometrioma, 15 studies deep endometriosis (endometriosis deeply situated in tissues in the pelvis) and 33 studies endometriosis at specific sites within the pelvic cavity. All studies included women of reproductive age who were undergoing diagnostic surgery because they had symptoms of endometriosis.

Key results

None of the imaging methods was accurate enough to provide this information on overall pelvic endometriosis. Transvaginal ultrasound identified ovarian endometriosis with enough accuracy to help surgeons determine whether surgery was needed, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was sufficiently accurate to replace surgery in diagnosing endometrioma but was evaluated in only a small number of studies. Other imaging tests were assessed in small individual studies and could not be evaluated in a meaningful way. Transvaginal ultrasound could be used to locate more anatomical sites of deep endometriosis when compared with MRI, helping surgeons better plan an operative procedure. Endometriosis in the lower bowel appears to be relatively accurately identified by both transvaginal and transrectal ultrasound, by MRI and by multi‐detector computerised tomography enema. New types of ultrasound and MRI show a lot of promise in detecting endometriosis but studies are too few to clearly show their diagnostic value.

Quality of the evidence

Generally the studies were of low methodological quality, and most imaging techniques were assessed by only a small number of studies. Differences between studies involved how they were run, groups of women studied, ways imaging tests were performed and how surgery was undertaken.

Future research

Additional high‐quality research is needed to accurately evaluate the diagnostic potential of non‐invasive imaging tests for endometriosis.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table: diagnostic tests for endometriosis.

| Review question | What is the diagnostic accuracy of the imaging tests in detecting endometriosis? | Pelvic endometriosis (any site and depth of invasion) | ||||||

| Ovarian endometriosis | ||||||||

| DIE | ||||||||

| Importance | A simple and reliable non‐invasive test for endometriosis with the potential to replace laparoscopy or to triage patients to reduce surgery would minimise surgical risk and reduce diagnostic delay | |||||||

| Participants | Women of reproductive age (1) with suspected endometriosis and/or (2) with persistent ovarian mass and/or (3) undergoing infertility workup | |||||||

| Settings | Hospitals (public or private of any level): outpatient clinics (general gynaecology, reproductive medicine, pelvic pain) and/or radiology departments | |||||||

| Reference standard | Visualisation of endometriosis at surgery (laparoscopy or laparotomy) with or without histological confirmation | |||||||

| Study design | Cross‐sectional of 'single‐gate' design (n = 28) or 'two‐gate' design (n = 1); prospective enrolment; 1 study could assess more than 1 test and/or more than 1 type of endometriosis | |||||||

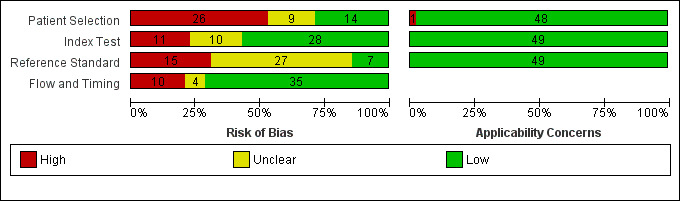

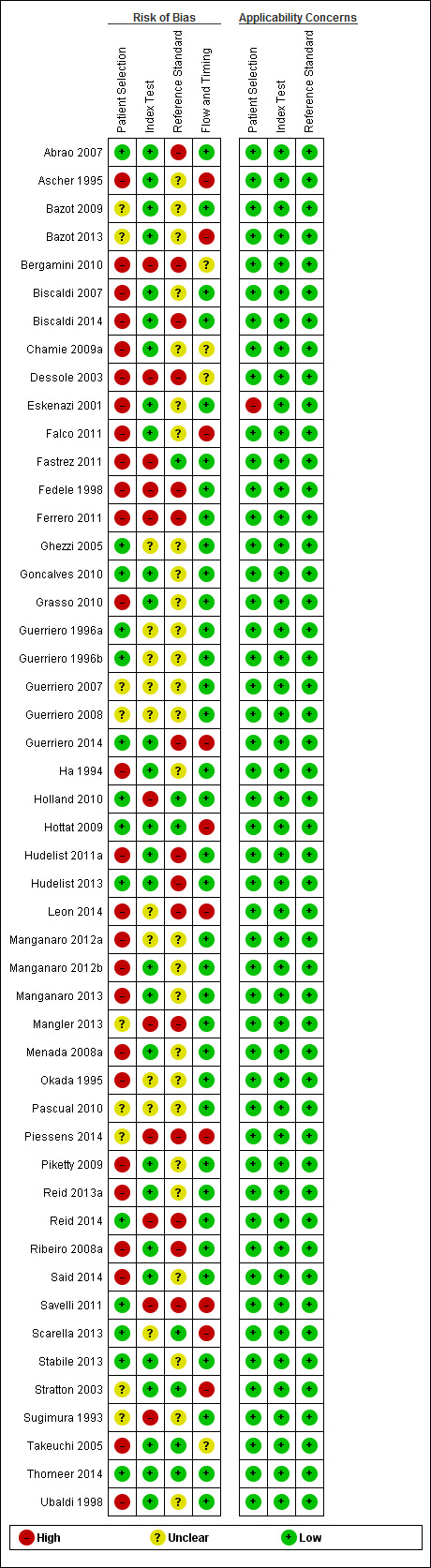

| Risk of bias and applicability concerns | Overall judgement | Poor quality of most studies (only 1 study had 'low risk' assessment in all 4 domains; Thomeer 2014) | ||||||

| Patient selection bias | High risk: 13 studies; unclear risk: 6 studies; low risk: 10 studies | |||||||

| Index test interpretation bias | High risk: 7 studies; unclear risk: 7 studies; low risk: 15 studies | |||||||

| Reference standard interpretation bias | High risk: 6 studies; unclear risk: 16 studies; low risk: 7 studies | |||||||

| Flow and timing selection bias | High risk: 9 studies; unclear risk: 2 studies; low risk: 18 studies | |||||||

| Applicability concerns | Concerns regarding patient selection: high concern ‐ 1 study, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 28 studies Concerns regarding index test: high concern ‐ 0 studies, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 29 studies Concerns regarding reference standard: high concern ‐ 0 studies, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 29 studies |

|||||||

| Diagnostic thresholds | Replacement test: sensitivity ≥ 94%; specificity ≥ 79% SnNout triage test: sensitivity ≥ 95%; specificity ≥ 50% SpPin triage test: sensitivity ≥ 50%; specificity ≥ 95% Approaching criteria for 1 of the above tests: diagnostic estimates within 5% of set thresholds |

|||||||

| Target condition | Test |

N of participants;

N of studies; N of data sets |

Pooled estimates (95% CI) | Outcomes | Implications | |||

| True positives (endometriosis) |

False positives (incorrectly classified as endometriosis) |

False negatives (incorrectly classified as disease‐free) |

True negatives (disease‐free) | |||||

| Pelvic endometriosis (13 studies, 1535 participants) | TVUS | 1222 participants in 5 studies |

Sens = 0.65 (0.27 to 1.00) Spec = 0.95 (0.89 to 1.00) Meta‐analysis of 4 studies after removing 1 outlier study Sens = 0.79 (0.36 to 1.00) Spec = 0.91 (0.74 to 1.00) |

257 | 24 | 372 | 569 | Approaches the criteria for a SpPin triage test when 1 outlier study was excluded. Wide confidence intervals (CIs) |

| MRI | 303 participants in 7 studies; 396 participants in 10 data sets |

Sens = 0.79 (0.70 to 0.88) Spec = 0.72 (0.51 to 0.92) |

253 | 21 | 70 | 52 | Neither replacement nor triage test criteria met Observation: 3.0T MRI (2 studies) demonstrated highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

| 18FGD PET‐CT | 10 participants in 1 study | Not availablea | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions | |

| Ovarian endometriosis (10 studies, 852 participants) | TVUS | 765 participants in 8 studies |

Sens = 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) Spec = 0.96 (0.92 to 0.99) |

182 | 28 | 16 | 539 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test and approaches the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test Observation: Studies published after 2006 (4 out of 5 studies) demonstrated highest diagnostic accuracy |

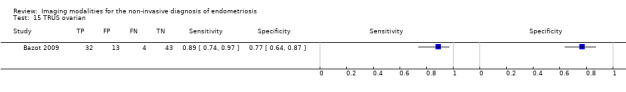

| TRUS | 92 participants in 1 study | Not availableb | 32 | 13 | 4 | 43 | Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions | |

| MRI | 179 participants in 3 studies |

Sens = 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) Spec = 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) |

72 | 9 | 4 | 94 | Meets the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test, approaches the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: 3.0T MRI (2 studies) demonstrated highest diagnostic accuracy Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

|

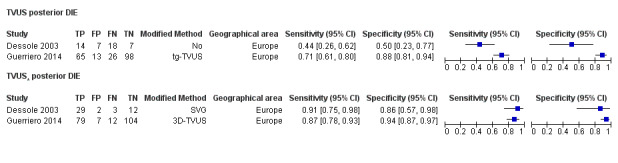

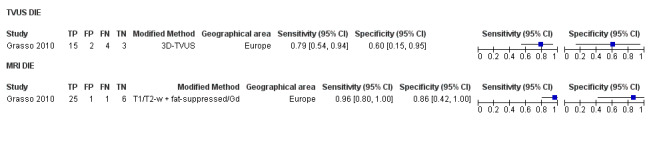

DIE/Posterior DIE (15 studies, 1493 participants) |

TVUS | 934 participants in 9 studies; 1383 participants in 12 data sets |

Sens = 0.79 (0.69 to 0.89) Spec = 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) |

435 | 51 | 128 | 769 | Approaches the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: TVUS‐BP (1 study) demonstrated highest diagnostic accuracy |

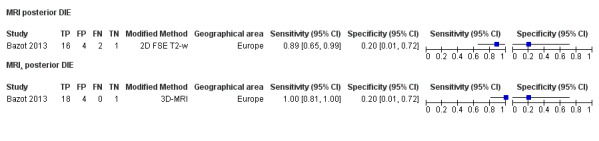

| MRI | 266 participants in 6 studies; 289 participants in 7 data sets |

Sens = 0.94 (0.90 to 0.97) Spec = 0.77 (0.44 to 1.00) |

210 | 11 | 9 | 59 | Approaches the criteria for a replacement and SnNout triage test Observation: 3.0T MRI (2 studies) and MRI jelly method (1 study) demonstrated highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

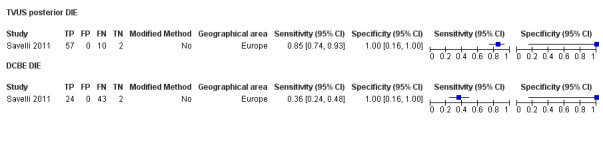

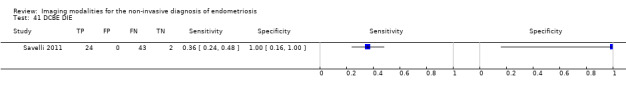

| DCBE | 69 participants in 1 study |

Not availablec | 24 | 0 | 43 | 2 | Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions | |

aFor FGD PET‐CT in pelvic endometriosis, diagnostic estimates were sensitivity = 0.00 (0.00 to 0.34); specificity = 1.00 (0.03 to 1.00)

bFor TRUS in ovarian endometriosis, diagnostic estimates were sensitivity = 0.89 (0.74 to 0.97); specificity = 0.77 (0.64 to 0.87)

cFor DCBE in DIE, diagnostic estimates were sensitivity = 0.36 (0.24 to 0.48); specificity = 1.00 (0.16 to 1.00)

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table: surgical mapping of endometriosis to specific anatomical sites.

| Review question | What is the diagnostic performance of the imaging tests in mapping deep endometriotic lesions in the pelvis at specific anatomical sites? | USL endometriosis | ||||||

| RVS endometriosis | ||||||||

| Vaginal wall endometriosis | ||||||||

| POD obliteration | ||||||||

| Anterior DIE | ||||||||

| RS/Bowel endometriosis | ||||||||

| Importance | Ability to diagnose DIE at specific anatomical sites at preoperative assessment helps optimise planning of surgery or guides referral to the most appropriate practice, with the potential to improve treatment outcomes | |||||||

| Participants | Women of reproductive age with suspected endometriosis or specifically suspected DIE | |||||||

| Settings | Hospitals (public or private of any level): outpatient clinics (general gynaecology, reproductive medicine, pelvic pain) and/or radiology departments | |||||||

| Reference standard | Visualisation of endometriosis at surgery (laparoscopy or laparotomy) with or without histological confirmation | |||||||

| Study design | Cross‐sectional of 'single‐gate' design (n = 33); prospective enrolment; 1 study could assess more than 1 test and/or more than 1 site of endometriosis | |||||||

| Risk of bias and applicability concerns | Overall judgement | Poor quality of most studies (only 1 study had 'low risk' assessment in all 4 domains; Thomeer 2014) | ||||||

| Patient selection bias | High risk: 16 studies; unclear risk: 6 studies; low risk: 11 studies | |||||||

| Index test interpretation bias | High risk: 8 studies; unclear risk: 4 studies; low risk: 21 studies | |||||||

| Reference standard interpretation bias | High risk: 14 studies; unclear risk: 14 studies; low risk: 5 studies | |||||||

| Flow and timing selection bias | High risk: 8 studies; unclear risk: 3 studies; low risk: 22 studies | |||||||

| Applicability concerns | Concerns regarding patient selection: high concern ‐ 0 studies, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 33 studies Concerns regarding index test: high concern ‐ 0 studies, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 33 studies Concerns regarding reference standard: high concern ‐ 0 studies, unclear concern ‐ 0 studies, low concern ‐ 33 studies |

|||||||

| Diagnostic thresholds | Replacement test: sensitivity ≥ 94%; specificity ≥ 79% SnNout triage test: sensitivity ≥ 95%; specificity ≥ 50% SpPin triage test: sensitivity ≥ 50%; specificity ≥ 95% Approaching criteria for 1 of the above tests: diagnostic estimates within 5% of set thresholds |

|||||||

| Target condition | Test |

N of participants;

N of studies; N of data sets |

Pooled estimates (95% CI) | Outcomes | Implications | |||

| True positives (endometriosis) |

False positives (incorrectly classified as endometriosis) |

False negatives (incorrectly classified as disease‐free) |

True negatives (disease‐free) | |||||

| USL endometriosis (11 studies, 997 participants) | TVUS | 751 participants in 7 studies | Sens = 0.64 (0.50 to 0.79) Spec = 0.97 (0.93 to 1.00) |

136 | 18 | 63 | 534 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: TVUS‐BP (1 study) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

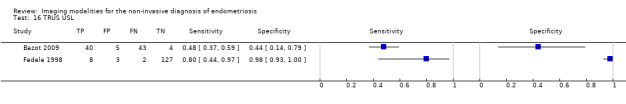

| TRUS | 232 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.52 (0.29 to 0.74) Spec = 0.94 (0.86 to 1.00) |

48 | 8 | 45 | 131 | Approchess the criteria for a SpPin triage test Wide CIs Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

| MRI | 199 participants in 4 studies 221 participants in 5 data sets |

Sens = 0.86 (0.80 to 0.92) Spec = 0.84 (0.68 to 1.00) |

136 | 13 | 22 | 50 | Criteria for a triage test not met Wide CIs Observation: 3.0T MRI (1 out of 2 studies) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

| RVS endometriosis (12 studies, 1215 participants) | TVUS | 983 participants in 10 studies 1073 participants in 11 data sets |

Sens = 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) Spec = 1.00 (0.98 to 1.00) |

263 | 10 | 59 | 741 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: TVUS‐BP (3 studies) and RWC‐TVS (1 study) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

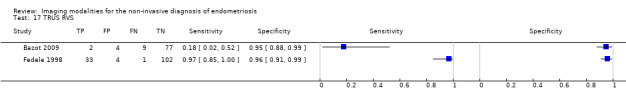

| TRUS | 232 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.78 (0.51 to 1.00) Spec = 0.96 (0.89 to 1.00) |

35 | 8 | 10 | 179 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

| MRI | 288 participants in 3 studies | Sens = 0.81 (0.70 to 0.93) Spec = 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) |

96 | 23 | 22 | 147 | Criteria for a triage test not met Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

|

Vaginal wall endometriosis (10 studies, 981 participants) |

TVUS | 679 participants in 6 studies | Sens = 0.57 (0.21 to 0.94) Spec = 0.99 (0.96 to 1.00) |

70 | 11 | 44 | 554 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Wide CIs Observation: tg‐TVUS (1 study) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

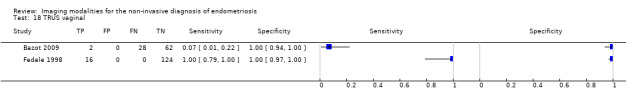

| TRUS | 232 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.39 (0.08 to 0.70) Spec = 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

18 | 0 | 28 | 186 | Criteria for a triage test not met Wide CIs Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

| MRI | 248 participants in 4 studies 271 participants in 5 data sets |

Sens = 0.77 (0.67 to 0.88) Spec = 0.97 (0.92 to 1.00) |

48 | 11 | 14 | 198 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: 3.0T MRI (1 study) and 3D‐MRI demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

|

POD obliteration (11 studies, 909 participants) |

TVUS | 755 participants in 6 studies | Sens = 0.83 (0.77 to 0.88) Spec = 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) |

152 | 17 | 32 | 554 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: TVUS‐BP ( 2 studies) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

| MRI | 154 participants in 5 studies 177 participants in 6 data sets |

Sens = 0.90 (0.76 to 1.00) Spec = 0.98 (0.89 to 1.00) |

84 | 3 | 12 | 78 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test and approaches the criteria for a SnNout triage test Observation: 3.0T MRI (3 studies) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

|

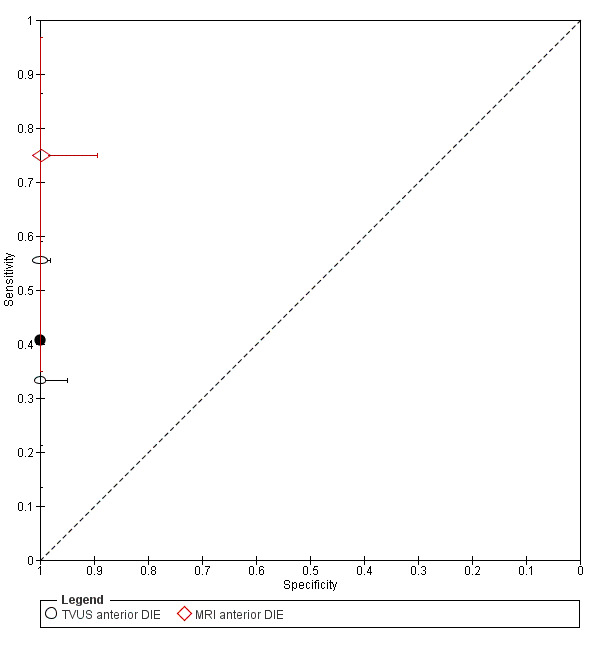

Anterior DIE (3 studies, 330 participants) |

TVUS | 289 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.41 (0.00 to 0.81) Spec = 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

11 | 0 | 16 | 262 | Criteria for a triage test not met Wide CIs Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

| MRI | 41 participants in 1 study | Not availablea | 6 | 0 | 2 | 33 | Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions | |

|

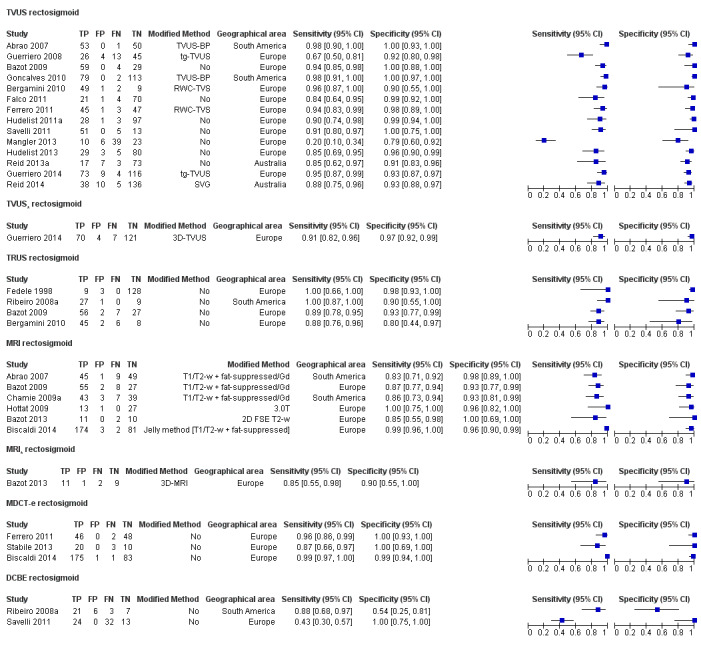

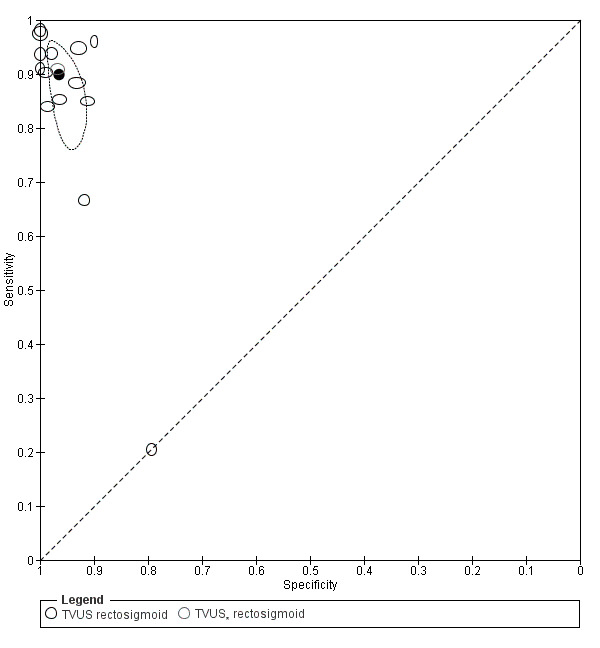

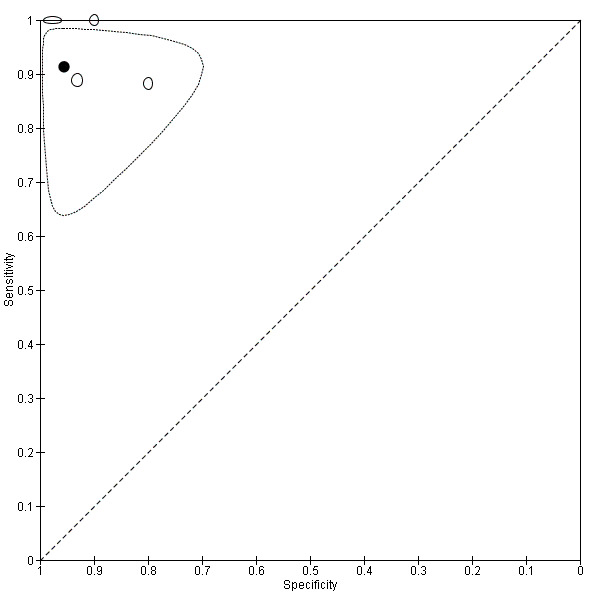

Rectosigmoid endometriosis (21 studies, 2222 participants) |

TVUS | 1616 participants in 14 studies 1817 participants in 15 data sets |

Sens = 0.90 (0.82 to 0.97) Spec = 0.96 (0.94 to 0.99) |

648 | 47 | 100 | 1022 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test and approaches the criteria for a SnNout triage test Observation: TVUS‐BP (2 studies) and RWC‐TVS (2 studies) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

| TRUS | 330 participants in 4 studies | Sens = 0.91 (0.85 to 0.98) Spec = 0.96 (0.91 to 1.00) |

137 | 8 | 13 | 172 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test and approaches the criteria for a SnNout triage test | |

| MRI | 612 participants in 6 studies 635 participants in 7 data sets |

Sens = 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) Spec = 0.96 (0.93 to 0.98) |

352 | 11 | 30 | 242 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test and approaches the criteria for a SnNout triage test Observation: MRI jelly method (1 study) and 3.0T MRI (1 study) demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy |

|

| MDCT‐e | 389 participants in 3 studies | Sens = 0.98 (0.94 to 1.00) Spec = 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) |

241 | 1 | 6 | 141 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin test and a SnNout triage test Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

| DCBE | 106 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.56 (0.32 to 0.80) Spec = 0.77 (0.41 to 1.00) |

45 | 6 | 35 | 20 | Criteria for a triage test not met Wide CIs Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

|

Bowel (ileum ‐ rectum) endometriosis (4 studies, 412 participants) |

TVUS | 314 participants in 3 studies | Sens = 0.89 (0.81 to 0.97) Spec = 0.96 (0.91 to 1.00) |

135 | 7 | 16 | 156 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin triage test Observation: TVUS, non‐modified method (1 study) demonstrated highest diagnostic estimates Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

| TRUS | 134 participants in 1 study | Not availableb | 72 | 0 | 3 | 59 | Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions | |

| MDCT‐e | 194 participants in 2 studies | Sens = 0.98 (0.92 to 1.00) Spec = 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

124 | 0 | 3 | 67 | Meets the criteria for a SpPin test and a SnNout triage test Insufficient evidence to allow meaningful conclusions |

|

aFor MRI in anterior DIE, diagnostic estimates were sensitivity = 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97); specificity = 1.00 (0.89 to 1.00)

bFor TRUS in bowel endometriosis, diagnostic estimates were sensitivity = 0.96 (0.89 to 0.99); specificity = 1.00 (0.94 to 1.00)

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined as an inflammatory condition characterised by endometrium‐like tissue at sites outside the uterus (Johnson and Hummelshoj 2013). Endometriotic lesions can be found at different locations, including the pelvic peritoneum and the ovary, or can penetrate pelvic structures below the surface of the peritoneum as deeply infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). Each of these types of endometriosis is thought to represent a separate clinical entity, but different types can co‐exist in the same woman. Pelvic endometriosis is defined as the presence of any endometrial tissue within the pelvic cavity, including the peritoneum, within any of the pelvic organs and inside the pouch of Douglas (POD). Ovarian endometriosis, an endometrioma, is defined as an ovarian cyst lined by endometrial tissue; it appears as ovarian masses of varying size. Endometriomas are identified more easily by imaging or by pelvic examination than are other forms of endometriosis; however, discrimination of benign ovarian endometriosis from other types of ovarian tumours can be challenging. DIE is defined as endometriotic tissue that penetrates the retroperitoneal space for a distance of 5 mm or more (Koninckx 1991) and may be present in multiple locations, involving anterior or posterior pelvic compartments, or both. Posterior DIE, a multi‐focal disease that may affect a variety of anatomical sites, represents the most common type of DIE (Kinkel 2006). The most typical sites of DIE include uterosacral ligaments (USL), rectovaginal septum (RVS), vaginal wall, POD and bowel, predominantly below the rectosigmoid junction. Anterior DIE corresponds to disease involving the anterior pouch or bladder and is much less common. Rarely, endometriotic implants can be found at more distant sites, including lung, liver, pancreas and operative scars, with consequent variation in presenting symptoms.

Endometriosis afflicts 10% of women of reproductive age, causing dysmenorrhoea (painful periods), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), chronic pelvic pain and infertility (Vigano 2004). The clinical presentation can vary from asymptomatic and unexplained infertility to severe dysmenorrhoea and chronic pain. Symptoms can occur with bowel or urinary symptoms, an abnormal pelvic examination or the presence of a pelvic mass; however, no symptom is specific to endometriosis. Prevalence of endometriosis in the symptomatic population is reported as 35% to 50% (Giudice 2004).

Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of developing several cancers (Somigliana 2006) and autoimmune disorders (Sinaii 2002). The presence of disease is associated with changes in immune response, vascularisation, neural function, peritoneal environment and eutopic endometrium, suggesting that endometriosis is a systemic, rather than a localised, condition (Giudice 2004). Endometriosis has a profound effect on psychological and social well‐being and imposes a substantial economic burden on society. Women with endometriosis incur significant direct medical costs from diagnostic and therapeutic surgeries, hospital admissions and fertility treatments; however, these costs are superseded by indirect costs of endometriosis, including absenteeism and loss of productivity (Gao 2006; Simoens 2012). In the United States, the financial burden of endometriosis is estimated at US $12,419 per woman (Simoens 2012).

Although the pathogenesis of endometriosis has not been fully elucidated, it is commonly thought that endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue contained within menstrual fluid flows retrogradely through the fallopian tubes and implants at an ectopic site within the pelvic cavity (Sampson 1927). However, this theory does not explain the fact that although retrograde menstruation is seen in up to 90% of women, only 10% of women develop endometriosis (Halme 1984). Evidence suggests that a variety of environmental, immunological and hormonal factors are associated with endometriosis (Vigano 2004), and genetic loci that confer risk of endometriosis have been identified (Nyholt 2012). The relative contributions of these and other causal factors remain to be elucidated.

Although it is impossible to time the onset of disease, on average, women have a six‐ to 12‐year history of symptoms before obtaining a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, which indicates considerable diagnostic delay (Matsuzaki 2006). Untreated endometriosis is associated with reduced quality of life and contributes to outcomes such as depression, inability to work, sexual dysfunction and missed opportunities for motherhood (Gao 2006).

Treatment of endometriosis

No cure for endometriosis is known. Treatment options include expectant management, pharmacological (hormonal) therapy and surgery (Johnson and Hummelshoj 2013). Treatment is individualised, taking into consideration the therapeutic goal (pain relief or subfertility) and the location of the disease. Current pharmacological therapies such as the combined oral contraceptive pill, progestogens, weak androgens and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists act to reduce the effects of oestrogen on endometrial tissues and to suppress menstruation. These drugs can ameliorate symptoms of dysmenorrhoea and chronic pelvic pain, but they are associated with side effects such as breast discomfort, irritability, androgenic symptoms and bone loss. Surgical excision of endometriotic lesions can reduce pain and improve fertility, but is associated with high recurrence rates of 40% to 50% at five years post surgery (Guo 2009; Duffy 2014). Early treatment of individuals with endometriosis improves pain levels and physical and psychological functioning. Furthermore, improvements in management of menstruation (use of the Mirena coil and continuous use of the combined contraceptive pill) and fertility preservation (oocyte vitrification) raise the possibility of suppressing the progression of endometriosis and prospectively managing subfertility among endometriosis sufferers. The potential success of these preventative strategies is dependent on an accurate and early diagnosis. A major impediment to earlier and more efficacious treatment of this disease is diagnostic delay due to the invasive nature of standard diagnostic tests (Dmowski 1997).

Diagnosis of endometriosis

Clinical history and pelvic examination can raise the possibility of a diagnosis of endometriosis, but heterogeneity in clinical presentation, high prevalence of asymptomatic endometriosis (2% to 50%) and poor association between presenting symptoms and severity of the disease contribute to the difficulty involved in obtaining a reliable diagnosis of endometriosis based solely on presenting symptoms (Spaczynski 2003; Fauconnier 2005; Ballard 2008). Although an abnormal pelvic examination correlates with the presence of endometriosis on laparoscopy in 70% to 90% of cases (Ling 1999), the differential diagnosis for most positive physical findings is wide. Furthermore, a normal clinical examination does not exclude endometriosis, as laparoscopically proven disease has been diagnosed in more than 50% of women with a clinically normal pelvic examination (Eskenazi 2001). A variety of tests utilising pelvic imaging, blood markers, eutopic endometrium characteristics, urinary markers or peritoneal fluid components have been suggested as diagnostic measures for endometriosis. Although large numbers of the reported markers have distinguished women with and without endometriosis in small pilot studies, many have not shown convincing potential as a diagnostic test when evaluated in larger studies by different research groups. The diagnostic value of these tests has not been fully systematically evaluated and summarised by Cochrane methods. Currently, no simple non‐invasive test for the diagnosis of endometriosis is routinely implemented in clinical practice.

Surgical diagnostic procedures for endometriosis include laparoscopy (minimal access surgery) or laparotomy (open surgery via an abdominal incision). Over the past several decades, laparoscopy has become an increasingly common procedure that has largely replaced traditional open surgery among women suspected of having endometriosis (Yeung 2009). Laparoscopy confers significant advantages over laparotomy, creating fewer complications and shorter recovery times. Furthermore, a magnified view at laparoscopy allows better visualisation of the peritoneal cavity. Despite continuing controversy in the literature with regard to the superiority of one surgical modality over another for treating women with pelvic disease, laparoscopy is the preferred technique for evaluating the pelvis and abdomen and for treating individuals with benign conditions such as ovarian endometrioma (Medeiros 2009). Surgery is also the only currently accepted way to determine the extent and severity of endometriosis. Several classification systems have been suggested for endometriosis (Batt 2003; Chapron 2003a; Martin 2006; Adamson 2008), but most researchers and clinicians use the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification, which is internationally accepted as a respected currently available tool for objective assessment of the disease (American Society for Reproductive Medicine 1997). The rASRM classification system considers appearance, size and depth of peritoneal or ovarian implants and adhesions visualised during laparoscopy (Table 3) and allows uniform documentation of the extent of disease. Unfortunately, this classification system has little value in clinical practice because of lack of correlation between laparoscopic staging, severity of symptoms and response to treatment (Vercellini 1996; Guzick 1997; Chapron 2003b). A recent endeavour to attain consensus around the optimal classification for endometriosis has been undertaken by the World Endometriosis Society (Johnson 2015).

1. Staging of endometriosis, rASRM classification.

| Peritoneum | Endometriosis | < 1 cm | 1‐3 cm | > 3 cm |

| Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Deep | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Ovary | R Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Deep | 4 | 16 | 20 | |

| L Superficial | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Deep | 4 | 16 | 20 | |

| Posterior Cul‐de‐sac Obliteration | Partial Complete | |||

| 4 40 | ||||

| Ovary | Adhesions | < 1/3 Enclosure | 1/3‐2/3 Enclosure | > 2/3 Enclosure |

| R Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Dense | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| L Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Dense | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| Tube | R Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Dense | 4a | 8a | 16 | |

| L Filmy | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Dense | 4a | 8a | 16 | |

| aIf the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube is completely enclosed, change the point assignment to 16 American Society for Reproductive Medicine 1997 | ||||

The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Special Interest Group for Endometriosis stated in its guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis that for women presenting with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis, a definitive diagnosis of most forms of endometriosis requires visual inspection of the pelvis at laparoscopy as the 'gold standard' investigation (Kennedy 2005). Currently, the visual or histological identification of endometriotic tissue in the pelvic cavity during surgery is not just the best available but the only diagnostic test for endometriosis that is used routinely in clinical practice.

Disadvantages of laparoscopic surgery include and are not limited to high cost, need for general anaesthesia and potential for adhesion formation post procedure. Laparoscopy has been associated with 2% risk of injury to pelvic organs, 0.001% risk of damage to a major blood vessel and a mortality rate of 0.0001% (Chapron 2003c). Only one‐third of women who undergo a laparoscopic procedure will receive a diagnosis of endometriosis; therefore, many disease‐free women are unnecessarily exposed to surgical risk (Frishman 2006)

The validity of laparoscopy as a reference test for endometriosis has been assessed as highly dependent on the skills of the surgeon. The diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopic visualisation has been compared with histological confirmation in a sole systematic review; 94% sensitivity and 79% specificity have been reported (Wykes 2004). Subsequent studies suggested that incorporation of histological verification into the diagnosis of endometriosis may improve diagnostic accuracy (Marchino 2005; Almeida Filho 2008; Stegmann 2008), but these papers have not been systematically reviewed. The clinical significance of histological verification remains debatable, and a diagnosis based on visual findings can be considered reliable with accurate inspection of the abdominal cavity by properly trained experienced surgeons (Redwine 2003). Furthermore, excised potentially endometriotic tissues are rarely serially sectioned in clinical practice, and small lesions can be missed by pathologists in cases of mild disease. Thus sampling inconsistencies are likely to influence the accuracy of histological reporting.

Summary

A diagnostic test in place of surgery would reduce associated surgical risks, increase diagnostic accessibility and improve treatment outcomes. The need for an accurate and non‐invasive diagnostic test for endometriosis continues to encourage extensive research in the field and was endorsed at the international consensus workshop at the 10th World Congress of Endometriosis in 2008 (Rogers 2009). Although multiple markers and imaging techniques have been explored as diagnostic tests for endometriosis, none of them have been implemented routinely in clinical practice, and many have not been subject to systematic review.

Index test(s)

This review assesses the diagnostic imaging techniques that have been proposed as non‐invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis (Table 4) as part of the review series on non‐invasive diagnostic tests for endometriosis. The other reviews from this series include 'Blood biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis', 'Endometrial biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis', 'Urinary biomarkers for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis' and 'Combination of the non‐invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis', which is the summary review for this series.

2. Index tests ‐ description and common abbreviations.

| Test name as presented in the review | Description | Alternative names presented in the included studies |

| MRI tests | ||

| MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) |

Equipment: 1.5 Tesla magnet device with a parallel or phased array body or pelvic coil for signal excitation and reception Participants’ preparation: Fasting for 3‐6 hours before the test and/or bowel preparation with oral laxatives was described by some investigators; an intravenous injection of anti‐peristaltic agent at the outset of the examination to decrease bowel peristalsis; supine position. Some groups performed MRI with full bladder to correct the angle of the ante‐flexed uterus; some groups described introducing of ultrasonographic gel (˜ 50 to 60 mL) into the vaginal canal to distend the vaginal fornices Protocol: Imaging is performed in the axial plane with or without sagittal or coronal planes. Different types of sequences allow to image the same tissue in various ways, and combinations of sequences reveal important diagnostic information about the tissue in question. The imaging parameters (section thickness, field of view (FOV), matrix size) vary between protocols. Images are documented on radiographic film and in digital files and analysed at workstation |

|

(conventional T1‐/T2‐weighted) |

The protocol includes axial spin‐echo or gradient echo T1‐weighted (T1‐w) images followed by fast spin‐echo (FSE)/turbo spin‐echo (TSE) images or fast relaxation fast‐spin echo (FR‐FSE) T2‐w images | MRI; CSE (conventlonal spin echo) |

(T1‐weighted) |

Protocol includes T1‐w imaging using chemical fat suppression, which aids in the differentiation of lipid and haemorrhagic pathologies. Fat suppression is a generic term that includes various techniques to suppress the signal from normal adipose tissue to reduce chemical shift artefact and can be achieved by various methods. This is commonly a part of the MRI protocol and is rarely used in isolation | Fat‐saturated MRI |

(T1‐/T2‐weighted with fat‐suppression contrast enhanced) |

Protocol includes gradient echo T1 images with and without fat suppression followed by FSE or FR‐FSE T2‐w images before and after intravenous injection of the paramagnetic contrast agent gadolinium | MRI; CSE/TIFS (conventlonal spin echo in combination with T1‐w fat‐suppressed) CSE/TIFS/Gd‐TIFS (conventlonal spin echo in combination with T1‐w fat‐suppressed and gadolinium‐enhanced TlFS) |

|

Protocol involves pretreatment of participants for MRI by simultaneous injection of ultrasonographic gel into the vagina (˜ 50 mL) and into the rectum (150 mL gel 50% diluted with water). Another technique evolves introduction of 300‐400 mL of diluted ultrasonographic gel (1:8 dilution) for rectosigmoid distension without use of intravaginal gel | MRI‐e (magnetic resonance enema) |

| 3D‐MRI (3‐dimensional MRI) | Protocol includes 3D coronal single‐slab (containing all the slices) MRI, entitled 'CUBE' with FSE T2‐w images. The technique involves using variable flip angle refocusing, auto‐calibrating, 2D accelerated parallel imaging and nonlinear view ordering to produce high‐resolution volumetric image data sets and to reduce imaging time by using multi‐planar reformations | |

| 3.0T MRI |

Equipment: 3.0Tesla Magnetom system with a multi‐channel phased‐array surface body‐coil Participants’ preparation: Fasting for 3 hours before the test was reported by some but not all studies; intravenous injection of anti‐peristaltic agent at the outset of the examination to decrease bowel peristalsis; administration of a negative super‐paramagnetic oral contrast agent to reduce signal intensity of the bowels. Examination with the full bladder in a ‘feet first’ supine position Protocol: combination of all or some of the following sequences: T‐w FSE, 2D‐T2‐w FR‐FSE/FSE, 3D‐T2‐w FR‐FSE CUBE, 3D‐T1‐w fat‐suppressed and/or LAVA‐flex (liver imaging with volume acceleration‐flexible) sequences. MRI images are acquired according to multiple scan planes, in particular axial, coronal and sagittal planes of the pelvis and sacral para‐coronal plane. Contrast agent (gadolinium) is administered in selected cases. Total acquisition time ˜ 20 min without or 30‐40 min with contrast injection |

|

| Ultrasound tests | ||

| TVUS (transvaginal ultrasonography) |

Equipment: any of the commercially available ultrasound machines equipped with a wide‐band high‐resolution vaginal transducer (brands of scanners and frequencies of transducers vary between studies) Participants' preparation: Examination is performed in a dorsal lithotomy position with empty or half‐full bladder; no bowel preparation is routinely required Protocol: An ultrasound gel is applied to the tip of the transducer probe to create a lubricating, acoustically correct interface with the tissue. Scans are obtained by inserting the transducer (protected by disposable thin cover) into the vagina, followed by sequential movement of the probe within the vaginal canal to allow systematic evaluation of pelvic structures (uterus and adnexal regions; attention paid to the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, vesicouterine pouch and uterosacral ligament). The technique involves longitudinal, transverse and angled movements of the probe with sliding up and down, back and forward to obtain both longitudinal and transversal scans of pelvic structures. Examination protocols vary between studies. Each examination is interpreted in real time and can be documented in printed photographs |

TVS 'transvaginal ultrasound' 'transvaginal sonography' |

(transvaginal ultrasonography with bowel preparation) |

Examination consists of TVUS combined with bowel preparation including the following: low‐residue diet for 1‐3 days, oral laxative on the eve of the examination, rectal enema within an hour before the examination or a combination of the above | |

(rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography) |

Examination consists of TVUS combined with bowel preparation and instillation of water contrast in rectum during TVUS; procedure does not require general anaesthesia Protocol: After the transducer is introduced into the vagina, a flexible thin catheter (18‐28 Ch) with a rubber balloon is inserted into the rectal lumen up to 20 cm from the anus (gel infused with lidocaine is used to facilitate passage of the catheter). Rectal water contrast of 100 to 300 mL of warm saline solution is instilled inside the balloon under ultrasonographic guidance to provide high‐definition images of the rectal wall and its layers. Back flow of the solution is prevented by placement of a Klemmer forceps on the catheter. Images are obtained before, during and after saline injection |

'transvaginal sonography with water‐contrast in the rectum' 'water‐contrast in the rectum during transvaginal ultrasonography' |

(sonovaginography) |

Examination consists of TVUS combined with the introduction of saline solution or gel to the vagina to create an acoustical window between the transvaginal probe and surrounding structures and to distend the vaginal walls, permitting enhanced visualisation of pelvic structures Protocol: Procedure involves introduction of a Foley catheter into the vagina followed by insertion of the transvaginal probe with further injection of 200‐400 mL of saline through the catheter by the assistant. To prevent reflux of saline solution from the vagina, the vaginal canal is closed with the operator’s hand. Alternative method involves placement of 20 mL of ultrasound gel into the posterior vaginal fornix with a plastic syringe, followed by insertion of a transvaginal probe. Reported procedure time ranges from 30 to 45 minutes |

'transvaginal sonography and acoustic window with intravaginal gel' |

(tenderness‐guided TVUS) |

Examination consists of TVUS combined with particular attention to the tender points evoked during examination Protocol: Larger amount of ultrasound gel (˜ 12 mL instead of the usual 4 mL) is introduced into the probe cover to create a stand‐off for visualisation of the near‐field area. The probe is inserted gently to avoid the risk of squeezing out the gel. After the initial sonographic evaluation, the participant is asked to inform the operator about the onset and site of any tenderness experienced during probe pressure within the posterior fornix. When tenderness is evoked, the sliding movement is stopped, and particular attention is paid to the painful site via gentle pressure with the probe’s tip to detect endometriosis lesions. Reported procedure time is 15 to 20 minutes in cases of suspected lesions, but less time when the examination is negative |

|

(3‐dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography) |

Equipment: An ultrasound scanner equipped with 3D/4D imaging modes and a wide‐band high resolution volume transvaginal transducer. The method enables the acquisition of ultrasonographic volumetric data that can be assessed off‐line; in most institutions used as an adjunct to 2D US Protocol: region‐of‐interest (ROI) is identified using a B‐mode scan and a transvaginal volume transducer. During the volumetric scan, the transducer carries out a series of parallel scans of varying speeds focusing on the ROI. The anatomical ROI is visualised on the monitor as a graphic containing the 3 orthogonal planes. During volumetric scans, the investigator adopts some expedients such as positioning the probe near the anatomical ROI and reducing or eliminating participant movements. The volume obtained is stored on a hard disk and displayed later using dedicated software |

|

(introital 3‐dimensional ultrasound) |

Examination is performed with the transducer placed on the perineum against the symphysis pubis (firmly but without causing significant discomfort). To acquire a correct volume, the symphysis pubis, urethra, vagina, and rectum should be visualised in the same image. Gain is adjusted and focal area is set to the region of interest, with the sweep angle set at 90 or 120 degrees to produce a multi‐planar image in 3 planes: longitudinal, transverse and coronal | |

| TRUS (transrectal ultrasonography) |

Equipment: An ultrasound scanner with a 2‐dimensional axial and sagittal convex high‐frequency probe with or without a rigid linear probe or a flexible endoscope with lateral view and a convex high frequency echo probe Participants' preparation: A low‐residue diet for 3 days before the examination with or without laxatives and/or rectal enema is reported in some but not all studies; several groups described using general or local anaesthesia for the procedure, and some groups used no analgesia Protocol: A gel‐filled rubber sheath or water‐filled balloon is placed over the tip of the transducer to obtain better visibility. The transducer is inserted into the rectum and is advanced until the midline image of the cervix is visualised in the longitudinal view. Pelvic structures are evaluated by moving the transducer along its longitudinal axis and rotating it 130° to 140° along the main axis in both axial and longitudinal planes. Alternative technique includes insertion of the flexible probe into the sigmoid colon, over the aortic bifurcation and/or the upper part of the body of the uterus, with subsequent slow withdrawal, allowing optimum imaging of rectal and sigmoid colon walls/pelvic structures, with instillation of water into the intestinal lumen and alternating use of several frequencies (e.g. 5, 7.5, 12 MHz) |

TRS (transrectal sonograph) Tr EUS (transrectal endoscopic ultrasonography) RES (rectal endoscopic sonography) REU (rectal endoscopic ultrasonography) |

| Other tests | ||

| MDCT‐e (multi‐detector computerised tomography enema) |

Equipment: multi‐detector computed tomograph, which has a 2‐dimensional array of detector elements that permits CT scanners to acquire multiple slices or sections simultaneously and greatly increase the speed of CT image acquisition (unlike the linear array of detector elements used in typical conventional and helical CT scanners) Participants’ preparation: low‐residue diet for 3 days and bowel preparation with an oral laxative day before the examination; intravenous injection of anti‐peristaltic agent during the test Protocol: colonic distension performed by introducing about 2000 mL of water at 37ºC into the left lateral decubitus position. All participants receive an intravenous injection of iodine‐containing contrast. Participants are scanned in supine position from the dome of the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis in the portal phase (40 seconds after the arterial peak). Scan parameters (collimation, rotation time, tube voltage, effective mAs) differ between studies. Estimated radiation exposure is calculated by the scanner using CT dose index and is saved to the dose report. Both axial plane and multi‐planar reconstructions (sagittal and coronal) are evaluated. Images are reviewed at a workstation |

MSCTe (multi‐slice computed tomography combined with colon distension by water enteroclysis) 'Water enema CT' |

| 18FDG‐PET (fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography) |

Equipment: PET‐computed tomograph Participants’ preparation: Fasting for at least 6 hours before the test; 18FDG (a glucose analogue) injection 60 min before the test Protocol: Acquisition is performed with the participant in supine position, from mid‐thigh to the base of the skull. No iodine‐based contrast is administered. CT parameters reported in a single included study are 120 kV, 120 mA, pitch 1.5:1, speed 15 mm/rot. The PET element operates in 2D mode for 4 minutes per bed position. Attenuation correction is based on CT data |

|

| DCBE (double‐contrast barium enema) |

Equipment: motorised tilting radiographic table and standard equipment for fluoroscopic and radiological examination Participants’ preparation: low‐residue diet for 1‐3 days before the examination with or without oral laxatives day before the procedure; an anti‐peristaltic agent is administered intravenously at the outset of the examination to decrease bowel peristalsis Protocol: The procedure is performed in 2 steps to obtain double contrast and involves change of participant positions to ensure detailed visualisation of all intestinal segments. Barium sulphate contrast (600 to 800 mL) is instilled into rectum with a gravity pressure in the left lateral decubitus position. Once the barium reached the hepatic flexure, the colon was drained by gravity to remove as much barium as possible from the rectal ampulla without clearing completely the rectosigmoid colon of barium. Room air is then gently insufflated into the colon. Sequential views of the bowel are obtained. Each colonic segment is viewed in detail on spot radiographs and in magnification images. The procedure lasts 15 to 20 minutes |

|

The definition of ‘non‐invasive’ varies between medical dictionaries, but the term refers to a procedure that does not involve penetration of skin or physical entrance into the body (McGraw‐Hill Dictionary of Medicine 2006; The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine 2008). Although some imaging tests are associated with an intracavitary approach (e.g. transvaginal, transrectal) and therefore are invasive by this definition, when compared with diagnostic surgery for endometriosis, these tests are generally considered to be 'non‐invasive' or 'minimally invasive'. For the purpose of these reviews, we will define all tests that do not involve anaesthesia and surgery as ‘non‐invasive’.

Advantages of using imaging tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis include that they are minimally invasive, readily available and more acceptable to women; provide a rapid result; and are more cost‐effective when compared with surgery. However, imaging testing is dependent on the skills of the operator and the ability of women to access appropriate radiology services. At this point in time, all imaging modalities have been assessed in a limited number of small studies, which vary in the type of imaging methods used and the anatomical locations evaluated.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography (US) (which includes transabdominal, transvaginal and transrectal approaches) are the most widely reported diagnostic modalities for endometriosis. A systematic review that primarily summarised the diagnostic performance of ultrasound for endometriosis‐associated ovarian masses (endometriomas) concluded that transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) has clinical utility in differentiating endometriomas from other types of ovarian cysts (Moore 2002). This review concentrated on studies that used transabdominal and transvaginal US with or without Doppler and did not include reports on other forms of ultrasound, nor did it evaluate non‐ovarian forms of endometriosis. Studies that evaluated the ability of ultrasound to detect endometriotic implants at other pelvic sites reported varying degrees of accuracy for deep endometriotic lesions and failure to detect small lesions and pelvic adhesions (Kinkel 2006). Because of high costs and limited availability, MRI is not frequently implemented in routine clinical practice; however, a growing number of studies suggest that it has a role in the diagnosis of deep endometriotic lesions and greater ability than other modalities to detect small lesions (Kinkel 2006). Recently, MRI was promoted as the non‐invasive imaging technique of choice for detection and classification of endometriosis (Saba 2014a). Several recent systematic reviews on imaging in endometriosis (Hudelist 2011b; Medeiros 2014; Guerriero 2015) and narrative reviews on the topic primarily addressed diagnostic performance of US and/or MRI for deep endometriosis, predominantly with bowel involvement.

To improve diagnostic performance, variations in ultrasound techniques have been used, including transvaginal ultrasonography with bowel preparation (TVUS‐BP) (Goncalves 2010), use of water contrast in the rectum (RWC‐TVS) (Menada 2008a) or vagina (sonovaginography (SVG)) (Dessole 2003) and three‐dimensional ultrasonography (3D‐US) (Grasso 2010). Several modifications have been made to conventional MRI such as use of T1/T2‐weighted (T1/T2‐w) images, including addition of fat suppression with or without contrast enhancement. Three‐dimensional MRI (3D‐MRI) has also been evaluated as a single test for endometriosis, and 3.0T MRI has been developed using the 3.0T Magnetom system (in contrast to the widely used 1.5T system) with incorporation of T1/T2‐w, fat‐suppressed and 3D sequences (Hottat 2009; Manganaro 2013; Thomeer 2014). Computed tomography (CT)‐based imaging (Biscaldi 2007), barium enema (Ribeiro 2008a) and other techniques have been explored as diagnostic tests for endometriosis. Improvements in imaging technology over time have positively affected the diagnostic ability of the same type of imaging test to detect endometriosis. Re‐evaluation of diagnostic test accuracy by Cochrane methods for a variety of imaging modalities is needed.

Clinical pathway

Women who present with symptoms of endometriosis (dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, difficulty conceiving) generally are investigated by a gynaecological examination and pelvic ultrasound scan to exclude other pathologies, in keeping with international guidelines (ACOG Committee on Gynecology 2010; SOGC 2010; Dunselman 2014). No other standard investigative tests are available, and MRI is used conservatively because of its cost. If women seek pain management rather than conception, empirical treatment with progestogens or the combined oral contraceptive pill is commonly started. Diagnostic laparoscopy is considered if empirical treatment fails, or if women decline or do not tolerate empirical treatment. In women who have difficulty conceiving, laparoscopy can be undertaken before fertility treatment is provided (particularly if severe pelvic pain or endometriomas are present) or after failed ART (assisted reproductive technology) treatment. Endometriosis can be diagnosed during fertility investigations in women who have minimal or no pain symptoms.

On average, a delay of six to 12 years is seen from onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis at surgery (Matsuzaki 2006). Rapid referral to a gynaecologist with the ability to perform diagnostic surgery is associated with shorter time to diagnosis (Greene 2009). Collectively, young women, women in remote and rural locations and women of lower socioeconomic status have reduced access to surgery and are less likely to obtain prompt diagnosis and/or localisation of endometriosis.

Prior test(s)

Most women who present with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis undergo a full history and physical examination and a routine gynaecological ultrasound before the decision is made to perform diagnostic surgery. However, no consensus exists on whether ultrasound or any other test should be used routinely as part of a standardised approach.

Role of index test(s)

A new diagnostic test can fulfil one of three roles.

Replacement: used to replace an existing test by providing greater or similar accuracy, along with other advantages.

Triage: used as an initial step in a diagnostic pathway to identify women who need to undergo further testing with an existing test. Although ideally a triage test has high sensitivity and specificity, it may have lower sensitivity but higher specificity than the current test, or vice versa. The triage test does not aim to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the existing test but rather to reduce the number of individuals undergoing an unnecessary diagnostic test.

Add‐on: used in addition to an existing test to improve diagnostic performance (Bossuyt 2008).

Ideally, a diagnostic test is expected to correctly identify all women with a specific disease and to exclude all who do not have that disease, in other words, it should have sensitivity and specificity of 100%. High sensitivity indicates that a small number of women who have a negative test do have the disease (i.e. small number of false‐negative results). High specificity corresponds to a small number of women who receive a positive test result but do not have the disease (i.e. small number of false‐positive results). In practice, however, it is extremely rare to find a test with equally high sensitivity and specificity. An acceptable replacement test would need to have similar or higher sensitivity and specificity than the current gold standard of laparoscopy. The only systematic review performed to determine the accuracy of laparoscopy in diagnosing endometriosis reported sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 79% (Wykes 2004), and we have used this as a cut‐off value for a replacement test.

The purpose of triage tests can vary depending on clinical context and patient priorities. One reasonable approach is to exclude the diagnosis to avoid further unnecessary and expensive diagnostic investigation. High‐sensitivity tests yield few false‐negative results and act to rule conditions out (SnNout). A negative result from a test with high sensitivity will exclude the disease with high certainty independent of the specificity. As women without disease would be assured of having a negative test, unnecessary invasive interventions can be avoided. However, a positive result has less diagnostic value, particularly when specificity is low. We predetermined that a clinically useful 'SnNout' triage test should have sensitivity of 95% or more and specificity of 50% or above. The sensitivity cut‐off for a 'SnNout' triage test was set at 95% or above, if it is assumed that a 5% false‐negative rate is statistically and clinically acceptable. The specificity cut‐off was set at 50% or above, to avoid diagnostic uncertainty about more than 50% of the population receiving a positive result.

An alternative approach would be to avoid a missed diagnosis. High‐specificity tests yield few false‐positive results and act to rule conditions in (SpPin). A positive result for a highly specific triage test indicates a high likelihood of endometriosis. This information could be used to prioritise women for surgical treatment. A positive 'SpPin' test could also provide a clinical rationale for starting targeted disease‐specific medical treatment for a woman without a surgical diagnosis, under the assumption that disease is present. Surgical management could be reserved for cases when conservative treatment fails. This is particularly relevant in some populations for which the therapeutic benefits of surgery for endometriosis have to be carefully balanced with the disadvantages (e.g. young women, women with medical conditions, pain‐free women with a history of infertility). In this scenario, we considered sensitivity of 50% or above and specificity of 95% or higher as suitable cut‐offs for a 'SpPin' triage test.

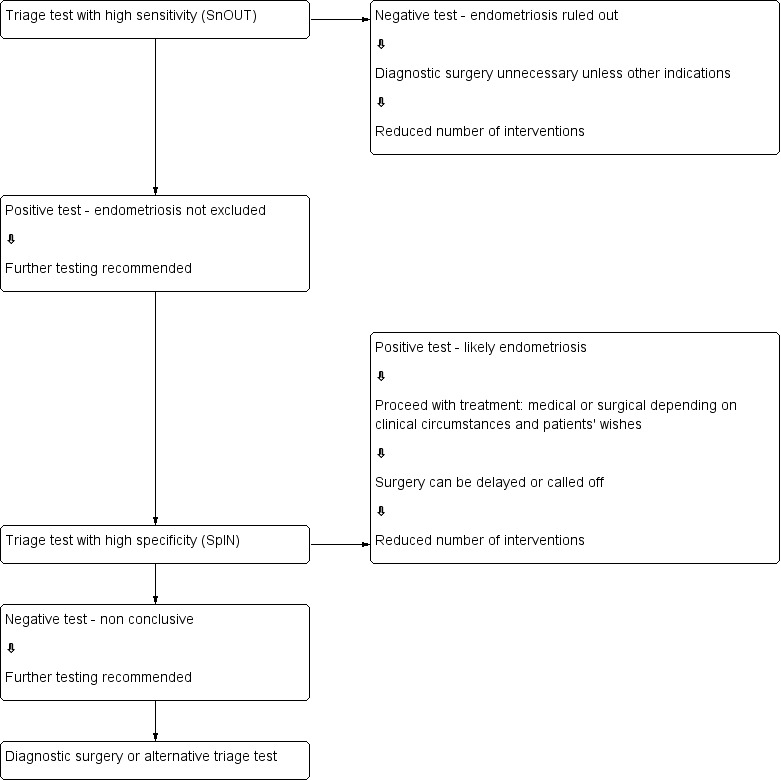

We evaluated imaging tests for their potential to replace surgery (replacement test) or to improve selection of women for surgery (triage test) that can rule out (SnNout) or rule in (SpPin) the disease. Both types of triage tests are clinically useful, minimising the number of unnecessary interventions. Sequential implementation of SnNout and SpPin tests can also optimise a diagnostic algorithm (Figure 1). We did not assess any test as an add‐on test, as we sought tests that reduce the need for surgery ‐ not tests that improve the accuracy of the currently available surgical diagnosis.

1.

Sequential approach to non‐invasive testing of endometriosis.

Knowledge of the accuracy of imaging index tests for detecting DIE at specific intrapelvic anatomical locations provides valuable information for surgeons, who can preoperatively arrange bowel preparation or availability of specialist surgical expertise for removal of lesions at particular locations. Surgical mapping of disease in isolated anatomical sites cannot exclude the disease somewhere else in the pelvis, hence it is not appropriate to use replacement test criteria for anatomical mapping, and we considered these types of tests only in the context of SnNout and SpPin triage criteria.

Alternative test(s)

No alternative tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis are available in routine clinical practice.

Rationale

Many women with endometriosis suffer long‐standing pelvic pain and infertility before they receive the diagnosis. Surgery is the only method currently used to diagnose endometriosis, but it is associated with high costs and surgical risks. A simple and reliable non‐invasive test for endometriosis with the potential to replace laparoscopy or to triage women to reduce surgery would minimise surgical risk and reduce diagnostic delay. Endometriosis could be detected at less advanced stages, and earlier interventions instituted. This would provide the opportunity for a preventative approach to this debilitating disease. Healthcare and social security costs of endometriosis would be expected to be reduced by early diagnosis and more cost‐effective and efficient treatments.

Accurate diagnostic tests are important in strategic considerations of treatment planning. Women with severe invasive disease particularly benefit from surgical management, the efficacy of which depends on the completeness of excision of endometriotic lesions (Garry 1997). Therefore, ability to diagnose deep infiltrating endometriosis in general and at specific anatomical sites in particular might lead to selection of surgical technique, involvement of a multi‐disciplinary surgical team or referral to the most appropriate practice (Chapron 2003a).

Objectives

Primary objectives

To provide the estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities for the diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis and deeply infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) versus surgical diagnosis as a reference standard.

To describe performance of imaging tests for mapping of deep endometriotic lesions in the pelvis at specific anatomical sites.

Imaging tests were evaluated as replacement tests for diagnostic surgery and as triage tests that would assist decision making regarding diagnostic surgery for endometriosis.

Secondary objectives

To investigate the influence of heterogeneity on the diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities for endometriosis. Potential sources of heterogeneity include the following.

Characteristics of the study population: age (adolescence vs later reproductive years); clinical presentation (subfertility, pelvic pain, ovarian mass, asymptomatic women); stage of disease (revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification system); geographic location of study.

Histological confirmation in conjunction with laparoscopic visualisation versus laparoscopic visualisation alone.

Changes in technology over time: year of publication; modifications applied to conventional imaging techniques.

Methodological quality: differences in the QUADAS‐2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies‐2) evaluation (low vs unclear or high risk); consecutive versus non‐consecutive enrolment; blinding of surgeons to results of index tests.

Study design ('single gate design' vs 'two‐gate design' studies).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published peer‐reviewed studies that compared results of one or several types of imaging tests versus results obtained from a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis.

We included studies if they were:

randomised controlled trials;

-

observational studies of prospectively recruited women of the following designs:

‘single gate design’ (studies with a single set of inclusion criteria defined by clinical presentation). All participants had clinically suspected endometriosis; or

‘two‐gate design’ (studies in which participants are sampled from distinct populations with respect to clinical presentation). The same study includes participants with a clinical suspicion of having the target condition (e.g. women with pelvic pain) and participants in whom the target condition is not suspected (e.g. women admitted for tubal ligation). Two‐gate studies were eligible only when all cases and controls belonged to the same population with respect to the reference standard (i.e. all participants were scheduled for laparoscopy) (Rutjes 2005).

performed in any healthcare setting; or

published in any language;

We did not impose a minimal limit on the number of participants in the included studies nor on the number of studies that have evaluated each index test.

We excluded the following studies.

-

Studies of specific study designs.

Narrative or systematic review.

Study of retrospective design when the index test was performed after execution of a reference test, or participants were selected through a retrospective review of case notes. Knowledge of the reference test could bias relatively subjective index tests. If endometriosis is found at a diagnostic surgical procedure, excision is commonly carried out concurrently, and this could bias the results of an index test performed after the reference standard.

Case report or case series.

Studies reported only in abstract form or in conference proceedings for which the full text was not available. This limitation was applied when we faced substantial difficulty in obtaining the information from abstracts, which precluded a reliable assessment of eligibility and methodological quality.

Participants

Study participants included women of reproductive age (puberty to menopause) with suspected endometriosis based on clinical symptoms and/or pelvic examination, who undertook both the index test and the reference standard.

Participants were selected from populations of women undergoing abdominal surgery for the following indications: (1) clinically suspected endometriosis (pelvic pain, infertility, abnormal pelvic examination or a combination of these), (2) ovarian mass regardless of symptoms, (3) a mixed group, which consists of women with suspected endometriosis/ovarian mass and/or women with other benign gynaecological conditions (e.g. surgical sterilisation, fibroid uterus).

Articles that included participants of postmenopausal age were eligible when data for the reproductive age group were available in isolation. Studies were excluded when the study population involved participants who clearly would not undergo the index test in a clinical scenario and/or would not benefit from the test (e.g. women with ectopic pregnancies, gynaecological malignancies, acute pelvic inflammatory disease). We also excluded publications in which only a subset of participants with a positive index test or reference standard were included in the analysis, and data for the whole cohort were not available.

Index tests

All types of imaging modalities for endometriosis, including possible modifications to conventional techniques, were assessed separately or in combination with other imaging tests. We attempted to group several types of tests that were based on common technical principles and similarity in clinical applicability. The index tests assessed are presented and described in Table 4.

We considered studies only if data were reported in sufficient detail for construction of 2 × 2 contingency tables. We included only studies that reported diagnostic accuracy estimates per number of participants ('participant‐level' analysis).

We undertook an independent evaluation of the diagnostic test accuracy of imaging tests to anatomically map endometriotic lesions because multiple endometriotic implants can co‐exist at different sites in the same individual. For this 'region level' analysis, only analyses that recorded data estimates per number of participants were included, as information about the accuracy of imaging tests for mapping the disease is more informative and clinically applicable when presented as per‐participant calculations of accuracy estimates.

Combined evaluations of imaging tests and other methods of diagnosing endometriosis (e.g. pelvic examination; urine, endometrial or blood tests) are beyond the scope of this review and are presented separately in another review titled 'Combined tests for the non‐invasive diagnosis of endometriosis'. We excluded from the review studies that solely assessed specific technical aspects, radiological criteria or interobserver variability of index tests without reporting data on diagnostic performance.

The diagnostic performance of an index test was considered high when the test reached the criteria for a replacement test (sensitivity ≥ 94% with specificity ≥ 79%) or a triage test (sensitivity ≥ 95% with specificity ≥ 50%, or vice versa). We categorised as 'approaching' high accuracy imaging tests with diagnostic estimates within 5% of set thresholds. We considered all other diagnostic estimates as low.

Target conditions

Investigators assessed three target conditions.

Pelvic endometriosis: defined as endometrial tissue located within the pelvic cavity, including any of the pelvic organs, peritoneum and pouch of Douglas.

Ovarian endometriosis (endometrioma): defined as ovarian cysts lined by endometrial tissue and appearing as an ovarian mass of varying size.

DIE: defined as subperitoneal infiltration of endometrial implants, for example, when endometriotic implants penetrate the retroperitoneal space for a distance of 5 mm or more. Posterior DIE is the most common form of DIE, and both conditions are interchangeably reported. For the purpose of this review, we combined them as a single target condition ‐ DIE/posterior DIE.

In addition, the ability of diagnostic imaging to map endometriotic lesions at specific anatomical pelvic locations was evaluated. Anatomical locations included rectovaginal septum (RVS), uterosacral ligament (USL), vaginal wall, POD obliteration, anterior DIE, rectosigmoid colon and the entire bowel from ileum to rectum. These locations are defined in Table 5.

3. Target conditions ‐ types and anatomical distribution of endometriosis.

| Type of endometriosis | Description |

| Main clinical types of endometriosis | |

| Pelvic endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions, deep or superficial, located at any site in pelvic/abdominal cavity: on the peritoneum, fallopian tubes, ovaries, uterus, bowel, bladder or PODa |

| Ovarian endometriosis | Ovarian cysts lined by endometrial tissue (endometrioma) |

| DIEb | Deep endometriotic lesions extending more than 5 mm under the peritoneum located at any site of pelvic/abdominal cavity |

| Subtypes of deep endometriosis per anatomical localisationc | |

| Posterior DIE | Deep endometriotic lesions involve ≥ 1 site of the posterior pelvic compartment (USLd RVSe, vaginal wall, bowel) and/or obliterate PODa |

| USLd endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions infiltrate uterosacral ligaments unilaterally or bilaterally |

| RVSe endometriosis | Deep endometriotic implants infiltrate the retroperitoneal area between posterior wall of vaginal mucosa and anterior wall of rectal muscularis |

| Vaginal endometriosisf | Endometriotic lesions infiltrate vaginal wall, particularly posterior vaginal fornix |

| PODa obliteration | Defined when the peritoneum of the PODa is only partially or no longer visible during surgery, and occurs as a result of adhesion formation; can be partial or complete, respectively |

| Bowel endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions infiltrating at least the muscular layer of the intestinal wall ileum ‐ rectum; predominantly affects rectosigmoid colon |

| Rectosigmoid endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions infiltrating at least the muscular layer of the rectosigmoid colon; the most common form of bowel endometriosis |

| Anterior DIE | Deep endometriotic lesions located at any site of the anterior pelvic compartment (bladder ± anterior pouch) |

| Rare types of endometriosis (not included in this review) | |

| Bladder endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions infiltrating bladder muscularis propria |

| Ureteral endometriosis | Endometriotic lesions involving ureters |