Abstract

Background

People with serious mental illness have consistently higher levels of mortality and morbidity than the general population. They have greater levels of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, diabetes, and respiratory illness. Although genetics may have a role in the physical health problems of these people, lifestyle and environmental factors such as smoking, obesity, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity play a prominent part.

Objectives

To review the effects of dietary advice for schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychosis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register (September 09, 2013 and February 24, 2016).

Selection criteria

We planned to include all randomised clinical trials focusing on dietary advice versus standard care.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors (RP, KTP) independently screened search results but did not identify any studies that fulfilled the review’s criteria.

Main results

We did not identify any studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Authors' conclusions

Dietary advice has been shown to improve the dietary intake of the general population. Research is needed to determine whether dietary advice can have a similar benefit in people with serious mental illness.

Plain language summary

Dietary advice for people with schizophrenia

The physical health of people with serious mental illness is often poor. Mortality levels remain about twice those of the general population. They are at greater risk of health problems such as heart disease, respiratory problems, and diabetes. The factors contributing to these health problems include higher levels of smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, and a nutritionally poor intake of food. The aim of this review was to determine whether offering dietary advice to people with schizophrenia would lead to an improvement in their dietary intake and health.

We ran a search for trials in 2013 using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's specialised register of trials. We looked for trials that randomised people with schizophrenia to receive either dietary advice plus their normal treatment or their normal treatment but without dietary advice. We did not include trials where dietary advice was given in combination with another treatment, for example, with exercise therapy.

We were unable to include any trials. Currently there is no good quality evidence available to help people determine if dietary advice is effective for people with schizophrenia. More research is needed.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Dietary Advice compared with no advice for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: participants with schizophrenia Settings: hospital or community Intervention: dietary advice Comparison: no dietary advice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard Care | Dietary Advice | |||||

| Improvement in nutritional intake | We found no relevant trials and therefore no data were available | |||||

| Change in measures of nutritional status: weight (kg), body mass index (kg/ m2), and waist/ hip ratio (cms) | No trial‐based data | |||||

| Mental state | No trial‐based data | |||||

| Clinically important adverse effects | No trial‐based data | |||||

| Measures of physiological function | No trial‐based data | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

There is now a greater focus on patients’ physical health by mental health services (The Schizophrenia Commission 2012). People with serious mental illness have consistently higher levels of mortality and morbidity than the general population. Mortality rates around twice those of the general population have been found (Saha 2007). The life expectancy of individuals with serious mental illness is 18.7 years shorter for men and 16.3 years shorter for women (Laursen 2011). Mortality rates remain unchanged despite the consistent reduction found in the general population during the past decades (Weinemann 2009). The widening differential gap in mortality suggests that people with schizophrenia have not fully benefited from the improvements in health outcomes available to the non‐mentally ill population (Saha 2007).

The underlying causes for the health problems of this population are both complex and multi‐factorial (Weinemann 2009). People with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, have higher levels of cardiovascular disease (Goff 2005; Leucht 2007a), metabolic disease (De Hert 2006), diabetes (Mukerjee 1996; Newcomer 2002), and respiratory illness (Chafetz 2008; Filek 2006). Although genetics may have a role in the physical health problems of these patients, lifestyle and environmental factors such as smoking, obesity, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity play a prominent part. Some of the treatments used in serious mental illness, such as neuroleptic medication, may also increase the risks of cardiovascular and metabolic disease (Weinemann 2009).

There is now a greater focus on attempting to improve the physical health of these patients. However they have less access to medical care, poorer quality of care, and preventative health checks are less commonly completed in both primary and secondary care than in the general population (Rummel‐Kluge 2010; Ussher 2011). The nature of their mental illness also affects their motivation to be able to improve their lifestyle (Paton 2004; Pearsall 2014). Individuals with serious mental illness have higher levels of smoking, weight problems, poor dietary intake, and low levels of physical activity. Rates of smoking of up to 70% have been found in patients with schizophrenia (Goff 2005; McCreadie 2003; Susce 2005). The prevalence of smoking in the general population is approximately 20% (Scottish Health Survey 2010). Levels of obesity range from 40% to 60%, up to four times that of the non‐mentally ill population (Green 2000). These individuals are less active with lower levels of physical activity compared to the general population (Daumit 2005).There is an increasing body of evidence to show that people with serious mental illness have a poorer diet. Many individuals with schizophrenia do not meet the recommended daily intake for fruit and vegetables (Brown 1999). Their diet is also higher in fat and lower in fibre than the general population. McCreadie 2003 found that not only did they have an unhealthy diet low in fruit and vegetables, but a nutritional intake poorer in milk, potatoes, and pulses. People with these conditions have also been found to have a diet with both a significantly higher total calorific intake and intake of carbohydrates and fat, compared to people in the general population (Srassnig 2003).

Description of the intervention

The aim of dietary advice is to promote the consumption of a healthy and balanced diet (Department of Health 2005). Dietary advice is defined as instruction in the modification of food intake. It may be given in a variety of forms, verbal or written, single or multiple contacts, with individuals or groups, provided by a dietician or other practitioner. Dietary advice should emphasise the importance of fruit and vegetables, fish (especially oily fish), starchy food such as bread, rice, and pasta, lower levels of dietary salt, and the consumption of a smaller proportion of foods containing saturated fat (Department of Health 2005)

How the intervention might work

Dietary advice has been shown to improve the dietary intake of individuals in the general population. Brunner et al (Brunner 2007) in a systematic review, studied 38 randomised controlled trials of interventions offering dietary advice (n = 17,871). They found an increase in the consumption of fruit and vegetables and fibre, and a reduction in total dietary fat following the provision of this advice. The dietary advice offered in these programmes varied in their form, intensity and duration. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Ammerman 2002 found that dietary advice increased the dietary intake of fruit and vegetables and reduced the intake of saturated and total fat. Other individual studies have found similar effects in the general population. In a study of 690 subjects, Huxley 2004 found an increase in the daily consumption of fruit and vegetables following the provision of dietary advice. Jenkins 2008 showed that a programme offering dietary advice led to an improvement in dietary intake of the participants, consisting of either a high fibre content (e.g. whole grain breads, brown rice and potatoes) or a low glycaemic index (e.g. oatmeal, pasta, rice, lentils and nuts). A study assessing the long‐term impact of a programme of dietary advice found that, even after 10 years, changes were found in dietary intake. They found that there was a persistent increase in the uptake of oily fish and cereal fibre intake following the intervention (Ness 2002).

At present research involving dietary advice has been limited in people with serious mental illness. In a small study of people taking clozapine medication, Heimberg 1995 found a reduction in weight gain following the provision of dietary advice.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to undertake this review for several reasons. A systematic review has been conducted investigating the effects of dietary advice for individuals in the general population but no comparable review is available for individuals with serious mental illness. The provision of dietary advice has been shown to improve the dietary intake of people in the general population. Improving dietary intake may lead to an improvement in morbidity or secondly a reduction in prevalent risk factors. For example, Brunner 2007 found that the provision of dietary advice resulted in a reduction in serum cholesterol levels and blood pressure. Hooper 2003 found in a systematic review that dietary advice lowered levels of morbidity and mortality in people who have already experienced a myocardial infarction. This advice consisted of a reduction in saturated fat, increased omega‐3 fat intake, and adoption of a Mediterranean diet. Joshipura 2001 reported in a large study of healthy subjects an inverse association between the consumption of fruit and vegetables (green, vitamin C‐rich fruit, and vegetables) and the risk of coronary heart disease.

Objectives

To review the effects of dietary advice for schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials. We intended to exclude quasi‐randomised studies such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week. If trials were described as 'double‐blind', but it was implied that the study was randomised, we would have included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantial difference within primary outcomes when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we intended to include these in the final analysis. If there was a substantial difference we would only use clearly randomised trials and would describe the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text.

Types of participants

People with schizophrenia or other types of schizophrenia‐like psychosis (e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used, age, ethnicity and sex. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994). If a study describes the participant group as suffering from 'serious mental illnesses' and does not give a particular diagnostic grouping, we would include these trials. The exception to this rule would be if the majority of those randomised clearly did not have a functional psychotic illness.

Types of interventions

Studies where the intervention was dietary advice, with the primary aim of changing and improving dietary (nutritional) intake. For this review we defined dietary advice as 'instruction in the modification of food intake, given with the aim of improving nutritional intake by a dietician or other health care professional'. We would consider studies if they compared dietary advice with standard care (without dietary advice). We would not include studies if the dietary advice was given in combination with additional interventions such as exercise, or in conjunction with oral dietary supplements (including polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia (Irving 2006).

Types of outcome measures

We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in this review.

Primary outcomes

1. Nutritional intake before and after the intervention.

2. Measures of nutritional status such as change of weight (kg), body mass index (kg/m2), and waist/hip ratio (cms).

Secondary outcomes

1. Leaving the studies early (any reason, adverse events, inefficacy of treatment).

2. Global state

2.1 Clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies). 2.2 Relapse (as defined by the individual studies).

3. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia)

3.1 Clinically important change in general mental state score 3.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 3.3 Average change in general mental state score 3.4 Clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 3.5 Average endpoint specific symptom score 3.6 Average change in specific symptom score

4. General functioning

4.1 Clinically important change in general functioning 4.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 4.3 Average change in general functioning score

5. Quality of life/satisfaction with treatment

5.1 Clinically important change in general quality of life 5.2 Average endpoint general quality of life score 5.3 Average change in general quality‐of‐life score

6. Cognitive functioning

6.1 Clinically important change in overall cognitive functioning 6.2 Average endpoint of overall cognitive functioning score 6.3 Average change of overall cognitive functioning score

7. Service use

7.1 Number of participants hospitalised

8. Adverse effects

8.1 Number of participants with at least one adverse effect 8.2 Clinically important specific adverse effects (cardiac effects, death, movement disorders, sedation, seizures, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count) 8.3 Average endpoint in specific adverse effects 8.4 Average change in specific adverse effects

9. Measures of physiological function (e.g. immune function, cardiac function, respiratory function, diabetes, and other indices of nutritional status, lipid levels, vitamin B12, folate, iron).

'Summary of findings' table

We aimed to use the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and used the GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from RevMan 5.1 (Review Manager) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effects of interventions examined and the sum of available data on all outcomes rated as important to patient care and decision making. We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Nutritional intake

Measures of nutritional status

Leaving the study early

Global state

Mental state

Quality of life

Adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of Trials

On September 09, 2013 and February 24, 2016, the information specialist searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia group's Trials Register using the following search strategy which has been developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

(*diet* OR *fruit* OR *vegetable* OR *fish* OR *carbohydrat* OR *nutrition* OR * eating* OR *feeding* OR *weight loss* OR *food* OR *fats* OR *fatty* OR *calori* OR *health promotion* OR *health education* OR *food supplement* OR *food habit* OR *weight management* OR (*formula* AND *food*)) in Title, Abstract and Index Terms of REFERENCE) AND (*diet* OR *fruit* OR *vegetable* OR *fish* OR *carbohydrat* OR *nutrition* OR *fats* OR *fatty* OR *health promotion* OR *health education* OR *weight management*) in Interventions of STUDY)

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonym keywords and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, hand‐searches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group’s Module). There are no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We examined the reference lists of all retrieved articles, clinical guidelines, and previous reviews of schizophrenia for additional trials.

2. Personal contact

We planned to contact the authors of significant included papers identified from trials and review articles found in the search and ask for their knowledge of other studies, published or unpublished, relevant to the review. We planned to contact other experts in the field for similar information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (RP and KTP) independently inspected citations identified from the search. We identified potentially relevant reports and ordered full papers for reassessment. RP and KTP independently assessed retrieved articles for inclusion according to the previously defined inclusion criteria. We intended to resolve any disagreement by consensus discussions with the other members of the review team (AP and JG). If it was impossible to resolve disagreements, we intended to add those studies to those awaiting assessment and contact the authors of the paper for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

If relevant studies had been found, reviewer authors RP and KTP would have extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, JG would independently extract data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. Again, we would discuss any disagreement, document decisions and, if necessary, contact authors of studies for clarification. With remaining problems JG would be asked to help to clarify issues and document these final decisions. We would extract data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but include them only if we independently had the same result. We planned to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies had been multi‐centre, where possible, we would have extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

RP and KTP would have extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We planned to included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument have been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the measuring instrument has not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial. Ideally the measuring instrument should either be: (i) a self‐report or (ii) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly; we planned to note in Description of studies if this is the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided to primarily use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We planned to combine endpoint and change data in the analysis as we intended, when possible, to use mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes often are not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to relevant data before inclusion. For all change scale data and endpoint scale data from studies with > 200 participants:

We would enter into the analysis all endpoint data from studies of at least 200 participants, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We would enter all change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed.

For endpoint scale data from studies with < 200 participants:

When a scale starts from the finite number zero, we would subtract the lowest possible value from the mean, and divide this by the standard deviation. Values lower than 1 strongly suggest a skew, and we would exclude these data. If this ratio was higher than one but lower than two, skew is suggested. We would enter these data and test whether inclusion or exclusion of such data changes the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio is larger than two, we would include these data because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

When a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); Kay 1986), which can provide values from 30 to 210, we would modify the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases, skew is present if 2 standard deviations (SD) > (S ‐ S min), where 'S' is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended, where possible, to convert variables that could be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we planned to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This would be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). Had data based on these thresholds not been available, we intended to use the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we planned to enter data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for dietary advice. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved'), we intended to report data where the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome. We would have noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (RP and KTP) planned to work independently to assess the risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters had disagreed, the final rating would be made by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group. If inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we planned to contact authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We would report non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, we would undertake resolution by discussion.

We planned to note the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes we planned to calculate a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). For continuous outcomes we intended to estimate the mean difference (MD) between groups. We prefer not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if scales of very considerable similarity were used, we would presume there was a small difference in measurement, and we would calculate effect size and transform the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments. We planned to use a random‐effects model to analyse individual results regardless of whether there was heterogeneity or not; this tends to be a conservative strategy and helps to takes into account that the trials had heterogenous designs and participant populations.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we planned to present data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We would also contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we intended to present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjust for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1 + (m ‐ 1)* ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported we would assume it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account intra‐class correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. This occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase has been carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants may differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials would not be appropriate if the condition of interest was unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects would be very likely in severe mental illness, we planned to only use data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we intended to present the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary we planned to simply add these and combine within the two‐by‐two table. We planned to combine continuous data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not intend to reproduce this data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We are forced to make a judgment where this is for the short‐term trials likely to be included in this review. Should more than 40% of data be unaccounted for we would not reproduce or use data within analyses, but would still use for the outcome 'leaving the study early'. If, however, more than 40% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 40%, we intended to mark such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome is between 0% and 40% and where these data are not clearly described, we planned to present data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early would all be assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcomes of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes the rate of those who stayed in the study would be used ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ for those who did not. We planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis testing to assess how prone the primary outcomes would be to change when we compared 'completer' data only to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

If attrition for a continuous outcome had been between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data were reported, we would have reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations were not reported, we planned to first try to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error and confidence intervals available for group means, and either P value or T value available for differences in mean, we intended to calculate them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: when only the standard error (SE) was reported, standard deviations (SDs) would be calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formula for estimating SDs from P values, T or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae did not apply, we intended to calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless intended to examine the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore planned not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, we would prefer to use the more sophisticated approaches. E.g. MMRM or multiple‐imputation to LOCF and would only present completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we would address this issue in the item "incomplete outcome data" of the risk of bias tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We planned to consider all included studies, hoping to use all studies together. Should clear unforeseen issues be apparent that may add obvious clinical heterogeneity, these issues would be noted, considered in analyses, and sensitivity analyses would be undertaken for the primary outcome.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

Graphs would be inspected to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We planned to investigate heterogeneity between studies by using the I2 method (Higgins 2003) and the Chi2 P value. The former provides an estimate of the percentage of variation in observed results thought unlikely to be due to chance. We intended to take a value equal to or greater than 50% to indicate heterogeneity, and explore reasons for this. If the inconsistency was high and clear reasons were found, data would be presented separately.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings has been influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not intend to use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size. In other cases, where funnel plots would be possible, statistical advice would be sought in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We intended to use a random‐effects model to synthesise data. Where available, we planned to base the analyses on intention‐to‐treat data from the individual studies. Data would be combined from included trials in a meta‐analysis if they were sufficiently homogeneous, both clinically and statistically.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Pre‐planned subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses should be performed and interpreted with caution because multiple analyses will lead to false positive conclusions (Oxman 1992). However we intended to perform the following subgroup analyses, where possible.

a. Male and female participants

b. Low weight/BMI and high weight/BMI

c. Type of antipsychotic medication

d. Dietetic trained practitioner and non‐dietetic trained practitioner

2. Regression analyses

If we have a sufficient number of trials (roughly 9 to 11) per independent variable, meta‐regression will be performed in the future, to determine whether various study‐level characteristics affect effect sizes. We intend to examine the following possible effect modifiers: subject age, weight level, and duration of illness. STATA would be used to perform the meta‐regression (STATA 2005).

Sensitivity analysis

Again, in future versions of this review, we plan to examine the robustness of our findings by excluding: (i) studies with less than 20% follow‐up on the variable at the time point and (ii) skewed data (iii) trials with a high risk of bias or where the overall risk of bias was unclear.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

A search for trials was run on September 09, 2013 and an update of this on February 24, 2016.

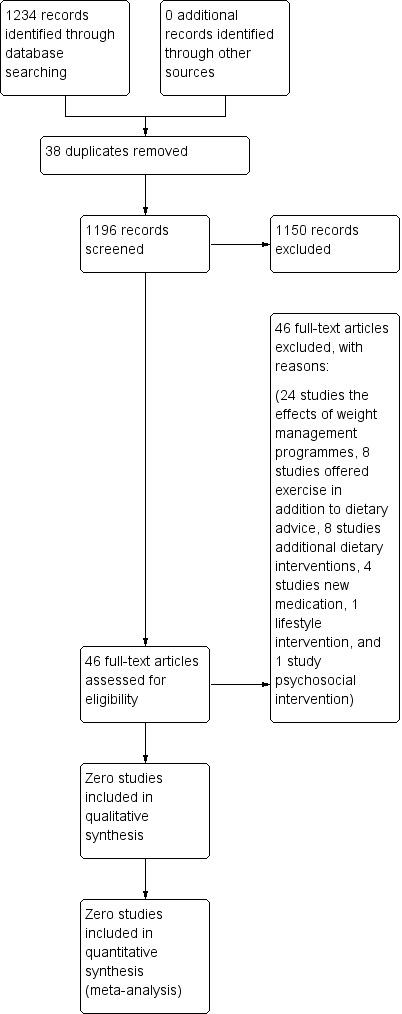

From the 2013 search, we inspected 1234 electronic reports. After removal of duplicates, we screened the articles and obtained 46 full text papers for assessment. We fully inspected these and initially excluded 43 studies. We subsequently excluded three further studies after a second assessment and detailed review of the interventions by two review authors (RP, KTP) (Scocco 2006; McCreadie 2005; McDougall 1992). We did not include any randomised controlled trials in this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The 2016 search found 124 new references, which were checked by editorial base of the Cochrane Schizophrenai Group. One possible ongoing trial was found (NCT02130596).

Included studies

No studies met the criteria for this review, suggestions for future trials are given in Table 2.

1. Suggested design of future study.

| Methods | Allocation – randomised, sequence generation described. Intervention ‐ non‐blinded. Study duration – 12 weeks. |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. N = * Age : 16‐65 years. Sex: both. |

| Intervention | Dietary advice incorporating verbal and written advice given at an educational session, once per week at a group meeting. |

| Outcomes | Change in dietary intake e.g. fruit and vegetables per day, intake of saturated fat per day. Measures of nutritional status such as change of weight (kg), body mass index (kg/ m2), and waist/hip ratio (cm). Mental state. Measures of physiological function. Adverse effects. Measures of physiological function. |

| Notes | * Size of study with sufficient power to detect a ˜ 10% difference between the two groups for primary outcome. |

We are aware of an ongoing trial that may meet our inclusion criteria (NCT02130596)

No trials await assessment.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 46 studies as most contained interventions in addition to dietary advice. Three of these studies were close to the inclusion criteria but we excluded them after detailed assessment. For example, we excluded Scocco 2006 as it contained advice on exercise in addition to dietary advice. We excluded the programme by McCreadie 2005 as, although they used dietary advice in one arm of the intervention, the primary component of the intervention was the provision of free fruit and vegetables. In the study McDougall 1992, in addition to the provision of dietary advice, part of the intervention included a shopping and lunch group.

Risk of bias in included studies

There were no studies that fulfilled the criteria for inclusion. We did not exclude any studies on the grounds of poor methodology.

Allocation

No studies met the eligibility criteria for this review.

Blinding

No studies met the eligibility criteria for this review.

Incomplete outcome data

No studies met the eligibility criteria for this review.

Selective reporting

No studies met the eligibility criteria for this review.

Other potential sources of bias

There were no studies that fulfilled the eligibility criteria for inclusion. We did not exclude any studies on the grounds of poor methodology.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Currently we know of no randomised studies describing the effects of dietary advice for schizophrenia.

Discussion

Summary of main results

No studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of three potentially eligible studies being identified but excluded after assessment. One possible study is ongoing and we await publication. We performed a comprehensive search to identify appropriate studies for inclusion in this review. However other factors may have affected the result such as the emphasis and use of only English phrases and language. It is unlikely however that any trials have been missed as the Cochrane Schizophrenia group's trial register does contains studies from several sources that are not primarily in English, and the group's trial search co ordinator codes non English language studies into English descriptors.

A number of limitations need to be acknowledged in this review. The inclusion criteria may have been too strict by excluding programmes that offered additional interventions. For example, several studies (Evans 2005; Kwon 2006; Vreeland 2003) described weight reduction trials or well‐being programmes involving dietary advice as a component of a multi‐modal intervention. We did not include these trials due to the likely effect of the additional interventions on the outcomes. Interventions in this field of psychological medicine are often focused on addressing prominent issues such as weight gain in this population. Therefore there is a tendency for proposed trials to include more than one component to address these problems rather than testing the efficacy of single interventions such as dietary advice.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

No studies met the eligibility criteria for this review.

Quality of the evidence

Several studies nearly met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. However these studies incorporated additional components thereby making it difficult to compare directly the efficacy of interventions offering dietary advice in people with schizophrenia.

Potential biases in the review process

In this review we used a comprehensive search strategy to identify all relevant studies within the Cochrane Schizophrenia group's trials register. It is unlikely we have missed any large studies in this field. We searched for abstracts in different languages and examined study references and abstracts to identify additional studies. It is possible that studies with negative outcomes have been conducted but remain unpublished. We may have excluded some studies as a result of potentially narrow inclusion criteria. Many studies were excluded as they contained additional components to dietary advice, such as exercise advice or the provision of additional shopping or cooking interventions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

At this point we are not aware of any other similar reviews or studies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review has identified an absence of randomised trials investigating the effect of dietary change as a single intervention in schizophrenia. Dietary advice is presently offered to people with serious mental illness but there is a lack of evidence to support these recommendations. Dietary advice has been used in a number of multi‐modal healthy living interventions but included other components such as exercise and weight reduction.

1. For people with schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia are given advice in clinical settings regarding their nutritional intake. Evidence of the benefits of dietary advice in their population is as yet limited and not established. The benefit of dietary advice has been shown in the general population and therefore people with schizophrenia may be able to infer a similar effect. However issues such as difficulties changing health behaviour and impaired levels of motivation in this population need to be considered.

2. For clinicians

Clinicians in the field of mental health should be aware that advice to improve the diet of people with schizophrenia is not supported by evidence from randomised controlled trials in this population. Although clinicians may currently be giving this advice, no controlled trial has established whether the provision of dietary advice leads to an improvement in the nutritional intake of people with schizophrenia. Therefore it remains unclear if dietary advice should be given and in what form or method of delivery should it be given.

3. For policy makers or managers

The benefit of dietary advice has been established in the general population. It is therefore important to determine whether this type of intervention leads to an improvement in the nutritional intake of individuals with schizophrenia. Dietary advice is currently being given by clinicians in health care settings. It is desirable that research should be carried out to establish whether dietary advice leads to change in this population, improves the health of these individuals, considers the issues of resources and costs of this type of programme.

Implications for research.

Future research is needed to determine the effect of dietary advice on people with schizophrenia. At this time interventions offer additional components making it difficult to compare the effect of this type of advice. It is important to determine whether the provision of dietary advice directly leads to a change in the nutritional intake in these individuals.

1. General

This review highlights the need for research in this field. Dietary intake is important in this population as it is implicated in their high rates of mortality and morbidity. Important action is needed to bring about change in this group and improve their dietary intake. Therefore it is important to undertake research to determine whether their dietary intake can be improved by the provision of dietary advice.

2. Specific

Dietary intake is an important cardiovascular risk factor for both the general population and for individuals with serious mental illness. This systematic review has shown the need for randomised trials to determine whether dietary advice leads to a change in the nutritional intake of individuals with serious mental illness. At this time no research has effectively determined whether there is a strong causal link between dietary advice and change in dietary intake. An example of a suitable trial design is given in Table 2. It is important to emphasise that the trial should be randomised, incorporating participants diagnosed with schizophrenia (using a standardised index of diagnostic classification). The provision of dietary advice should involve verbal or written advice delivered in person or via the phone, to individuals or small groups. Outcome measures should use standardised measurement of change in dietary intake, or weight.

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's editorial base in Nottingham, United Kingdom, produces and maintains standard text for use in the methods sections of their reviews. This text has been used as the basis for parts of this review and adapted as required.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| 09723 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people on antipsychotic medication. Intervention: nursing intervention of antipsychotic‐induced weight gain. |

| 17224 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with first episode schizophrenia. Intervention: nursing intervention with olanzapine induced weight‐gain. |

| Baptiste 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders treated with antipsychotic medication. Intervention: weight reduction/ metabolic programme including dietary advice. |

| Brar 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had been switched from olanzapine to risperidone. Intervention: intervention comprised a group‐based weight loss intervention. |

| Brown 2011 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with serious mental illness. Intervention: intervention included an exercise component in trial. |

| Castrogiovanni 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people being treated with olanzapine. Intervention: intervention comprised a psychoeducational programme for prevention of weight gain on olanzapine. |

| Cordes 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight management programme incorporating an exercise component. |

| Daumit 2013 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with serious mental illness. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight management programme incorporating an exercise component. |

| Eli Lilly 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine. Intervention: intervention assessing the safety and efficacy of therapy for the prevention of weight gain associated with olanzapine. |

| Evans 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people commencing on olanzapine medication. Intervention: weight management intervention included a component of exercise advice. |

| Fan 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with first episode schizophrenia treated with olanzapine. Intervention: intervention included additional components as part of a weight reduction programme. |

| Gandelman 2009 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder who were already receiving oral ziprasidone. Intervention: cross‐over study, intervention included changes in dietary intake. |

| Ganguli 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention included additional measures to achieve weight reduction. |

| Ganguli 2009 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention included weight reduction measures in addition to dietary advice. |

| Ganguli 2011 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight loss programme, with additional components to the provision of dietary advice. |

| Goetz 2011 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight loss programme with additional components to improve nutrition and physical activity status. |

| Iglesias‐Garcia 2010 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with chronic schizophrenia. Intervention: structured educational programme providing information and counselling on three domains: nutrition, exercise and healthy habits, and self‐esteem. |

| Kelly 2002 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia in supported accomodation. Intervention: intervention included the provision of fruit and vegetables in addition to dietary advice. |

| Khazaal 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people treated with antipsychotic drugs. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight reduction programme using CBT. |

| Klaras 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight reduction and lifestyle modification programme. |

| Kwon 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders treated with olanzapine. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight management programme including an exercise component. |

| McCreadie 2005 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Intervention: intervention provided free fruit and vegetables against control. Second intervention arm comprised provision of dietary/nutritional advice + instruction on preparation of food. |

| McDougall 1992 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with chronic schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention comprised dietary advice and a practical component e.g. shopping practice, lunch group. |

| NCT00158366 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight reduction programme, to control participants' diet and increase their physical activity. |

| NCT00169702 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention comprised a weight management programme to prevent weight gain and metabolic abnormalities. |

| NCT00177905 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Intervention: intervention determined the effectiveness of a behavioural treatment (BT) for weight loss. |

| NCT00191828 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people treated with olanzapine medication. Intervention: intervention comprised prevention of weight gain using a psychoeducation programme. |

| NCT00485823 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Intervention: intervention comprised weight management programme including advice on physical activity. |

| NCT00572247 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention included education on nutrition and physical activity. |

| NCT00790517 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: lifestyle intervention with additional components. |

| NCT00990925 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention consisted of a nutrition, lifestyle, and medication programme. |

| NCT01052714 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with mental illness. Intervention: intervention consisting of a lifestyle modification programme including an exercise component. |

| NCT01075295 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with early schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Intervention: behavioural Intervention for the prevention of weight gain including exercise counselling. |

| NCT01272752 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: trial of new investigational product. |

| NCT01272765 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: trial of new investigational product. |

| NCT01324973 | Allocation: randomised. Participants:people with mental illness. Intervention: intervention included diet and exercise advice. |

| NCT01368406 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention consisted of a lifestyle modification programme in addition to dietary advice. |

| NCT01491490 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with mental illness. Intervention: trial of new investigational product. |

| Pfizer 2007 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: patients taking oral ziprasidone. Intervention: cross‐over study of effect of dietary intake on medication. |

| Rossotto 2003 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: psychosocial intervention reducing rehospitalisation rates. |

| Rotatori 1980 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people living in a psychiatric residential unit. Intervention: intervention included advice on exercise. |

| Scocco 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: intervention contained advice on exercise in addition to dietary advice. |

| Wang 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: behavioural intervention for weight reduction. |

| Weber 2006 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders taking antipsychotic medication. Intervention: CBT programme including advice on increasing activity. |

| Zhang 2008 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with first episode schizophrenia (inpatients). Intervention: psychoeducational programme aimed at weight reduction. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT02130596.

| Trial name or title | An acceptance based behavioural intervention versus nutritional counselling for weight loss in psychotic illness. |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. |

| Participants | Participants: people with psychotic illness, BMI > 25.0 |

| Interventions | 1. Acceptance based behavioural intervention. 2. Nutritional counselling. |

| Outcomes | Not provided. |

| Starting date | 2014. |

| Contact information | R. Ganguli: Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Canada. |

| Notes | Study has now been completed. Authors to be contacted for more information. |

Differences between protocol and review

There are no major methodological differences between the protocol and review. We added adverse effects to our outcomes of interest and have updated the methods text to reflect the latest template provided by the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group.

Contributions of authors

RP: developed and conducted the research, conducted the analysis, drafted and completed the manuscript. KTP: conducted the analysis, provided input and approved the final version. AP: developed research, provided input and approved final version of manuscript. JG: developed the research, provided input and approved final version of manuscript.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No financial support provided, Other.

External sources

No sources of support, Other.

No financial support provided, Other.

Declarations of interest

RP declared no competing interests. KTP declared no competing interests. AP declared no competing interests. JRG currently receives research funding from UK Medical Research Council, UK Economic and Social Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. He was expert witness for Dr Reddys Laboratories and is Chief Investigator on the CEQUEL trial to which GlaxoSmithKline have contributed and supplied investigational drugs and placebo.

New

References

References to studies excluded from this review

09723 2005 {published data only}

- 09723. Nursing intervention of antipsychotic‐induced weight gain. Shandong Archives of Psychiatry 2005;18(4):272. [Google Scholar]

17224 2005 {published data only}

- 17224. A study on the nursing intervention with the olanzapine induced weight‐gain. Journal of Nursing Science 2005;20(11):42‐3. [Google Scholar]

Baptiste 2006 {published data only}

- Baptiste JM, Liskov E, Chakunta UR, Hassan AQ, Brownell K, Wexler BE. Pilot study to investigate the effects of a weight management program in conjunction with food provision on cardiovascular and endocrine risk factors in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who are treated with antipsychotic medications. Proceedings of the 159th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2006 May 20‐25; Toronto, Canada. 2006.

Brar 2005 {published data only}

- Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Berry S, Mahmoud R. Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2005;66(2):205‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2011 {published data only}

- Brown C, Goetz J, Hamera E. Weight loss intervention for people with serious mental illness: a randomized controlled trial of the renew program. Psychiatric Services 2011;62(7):800‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Castrogiovanni 2006 {published data only}

- Castrogiovanni S, Simoncini M, Iovieno N, Cecconi D, Dell'Agnello G, Donda P, et al. Efficacy of a psychoeducational program for weight loss in patients who have experienced weight gain during treatment with olanzapine. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;16:S441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cordes 2008 {published data only}

- Cordes J. Efficacy of the BELA weight management programme to prevent increase of weight in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine (BELA = movement ‐ nutrition ‐ learning ‐ accepting). http://www.controlled‐trials.com 2008.

Daumit 2013 {published data only}

- Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, et al. A behavioral weight‐loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. New England Jourrnal of Medicine 2013;368(17):1594‐1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eli Lilly 2006 {published data only}

- Eli Lilly. Assessment of safety and efficacy of therapy for the prevention of weight gain associated with olanzapine. Eli Lilly and Company Clinical Trial Registry 2006.

Evans 2005 {published data only}

- Evans S, Newton R, Higgins S. Nutritional intervention to prevent weight gain in patients commenced on olanzapine: a randomized controlled trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2005;39(6):479‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fan 2005 {published data only}

- Fan A. Nursing intervention on the weight of the obese patients olanzapine. Journal of Nursing Science 2005;20(11):42‐3. [Google Scholar]

Gandelman 2009 {published data only}

- Gandelman K, Alderman JA, Glue P, Lombardo I, LaBadie RR, Versavel M, et al. The impact of calories and fat content of meals on oral ziprasidone absorption: a randomized, open‐label, crossover trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2009;70(1):58‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ganguli 2005 {published data only}

- Ganguli R, Brar JS. Prevention of weight gain, by behavioral interventions, in patients starting novel antipsychotics. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2005;31:561‐2. [Google Scholar]

Ganguli 2009 {published data only}

- Ganguli R, Brar JS. Weight maintenance by booster behavioral sessions in schizophrenia subjects who lost weight in a behavioral program. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2009;35:41. [Google Scholar]

Ganguli 2011 {published data only}

- Ganguli R, Brar JS. Weight reduction in schizophrenia, by lifestyle change: a randomized clinical trial. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 2011;2:153. [Google Scholar]

Goetz 2011 {published data only}

- Goetz J, Brown C, Hamera E. Preliminary 1‐year results of the renew program for weight loss. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2011;1:304. [Google Scholar]

Iglesias‐Garcia 2010 {published data only}

- Iglesias‐Garcia C, Toimil‐Iglesias A, Alonso‐Villa MJ. Pilot study of the efficacy of an educational programme to reduce weight, on overweight and obese patients with chronic stable schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing 2010;17(9):849‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kelly 2002 {published data only}

- Kelly C. A randomised control trial. National Research Register 2002; Vol. 3.

Khazaal 2007 {published data only}

- Khazaal Y, Fresard E, Rabia S, Chatton A, Rothen S, Pomini V, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophria Research 2007;91(1‐3):169‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klaras 2006 {published data only}

- Klaras ES, Kovac J, Plommon M, Nilsson PM, Ostapowicz A. The effect of lifestyle intervention to prevent weight gain during treatment with atypical antipsychotic drugs ‐ a randomized study. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;16:S413. [Google Scholar]

Kwon 2006 {published data only}

- Kwon JS, Choi J‐S, Bahk W‐M, Kim CY, Kim CH, Shin YC, et al. Weight management program for treatment‐emergent weight gain in olanzapine‐treated patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 12‐week randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2006;67(4):547‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCreadie 2005 {published data only}

- McCreadie RG, Kelly C, Connolly M, Williams S, Baxter G, Lean M, et al. Dietary improvement in people with schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 2005;187(4):346‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDougall 1992 {published data only}

- McDougall S. The effect of nutritional education on the shopping and eating habits of a small group of chronic schizophrenic patients living in the community. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 1992;55(2):62‐8. [Google Scholar]

NCT00158366 {published data only}

- NCT00158366. A clinical trial of weight reduction in schizophrenia. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2005.

NCT00169702 {published data only}

- NCT00169702. The effect of a weight management program to prevent weight gain and metabolic abnormalities during treatment with the atypical neuroleptic olanzapine: a randomised study. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2005.

NCT00177905 {published data only}

- NCT00177905. A clinical trial of weight reduction in schizophrenia. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2005.

NCT00191828 {published data only}

- NCT00191828. A prospective/parallel study on induced weight gain during atypical antipsychotic treatment and its management with psychoeducational programme. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2005.

NCT00485823 {published data only}

- NCT00485823. The assessment of a weight management program for treatment‐emergent weight gain in patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, and schizoaffective disorder during olanzapine therapy. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2007.

NCT00572247 {published data only}

- NCT00572247. The psychiatric rehabilitation approach to weight loss. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov 2007.

NCT00790517 {published data only}

- NCT00790517. Reducing weight and diabetes risk in an underserved population (STRIDE). http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Vol. 2008.

NCT00990925 {published data only}

- NCT00990925. Lifestyle modification for weightloss in schizophrenia. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2009.

NCT01052714 {published data only}

- NCT01052714. Healthy lifestyles for mentally ill people who have experienced weight gain from their antipsychotic medications. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2010.

NCT01075295 {published data only}

- NCT01075295. Prevention of weight gain in early schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. 2010.

NCT01272752 {published data only}

- NCT01272752. Anti‐psychotic medication (new use) weight loss study. http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01272752. 2011.

NCT01272765 {published data only}

- NCT01272765. Anti‐psychotic medication (stable dose) weight loss study. http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01272765. 2011.

NCT01324973 {published data only}

- NCT01324973. Web‐based weight management for individuals with mental illness. http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01324973. 2011.

NCT01368406 {published data only}

- NCT01368406. Lifestyle intervention for weight gain management for patients with schizophrenia. http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01368406. 2011.

NCT01491490 {published data only}

- NCT01491490. Treatment on iatrogenic weight gain and dyslipidaemia associated with olanzapine. http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01491490. 2011.

Pfizer 2007 {published data only}

- Pfizer. A phase II, open‐label, randomized, 6‐way crossover study to estimate the impact of total calories and fat content on the steady‐state serum concentrations of ziprasidone in patients receiving oral ziprasidone 80 mg bid. http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org/ 2007.

Rossotto 2003 {published data only}

- Rossotto E, Wirshing D, Wirshing W, Boyd J, Liberman R, Marder S. Reducing rehospitalization rates for patients with schizophrenia: the community re‐entry supplemental intervention. Schizophrenia Research 2003;60(1):328. [Google Scholar]

Rotatori 1980 {published data only}

- Rotatori AF, Fox R, Wicks A. Weight loss with psychiatric residents in a behavioral self‐control program. Psychological Reports 1980;46(2):483‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scocco 2006 {published data only}

- Scocco P, Longo P, Caon F. Weight change in treatment with olanzapine and a psychoeducational approach. Eating Behaviours 2006;7:115‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2008 {published data only}

- Wang BH//Du GP. Behavioural intervention for antipsychotic caused weight gain. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Health 2008;20(18):2117‐8. [Google Scholar]

Weber 2006 {published data only}

- Weber M, Wyne K. A cognitive/behavioral group intervention for weight loss in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophrenia Research 2006;83(1):95‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2008 {published data only}

- Zhang C, Fan M, Cao H. The effect of the psychological intervention on losing weight with antipsychotic. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology 2008;16(2):126‐8. [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

NCT02130596 {unpublished data only}

- NCT02130596. An Acceptance‐Based Behavioral Intervention vs. Nutritional Counselling for Weight Loss in Psychotic Illness. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT02130596 [Date Accessed: 24 February 2016].

Additional references

Altman 1996

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Detecting skewness from summary information. BMJ 1996;313(7066):1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ammerman 2002

- Ammerman AS, Lindquist CH, Lohr KN, Hersey J. The efficacy of behavioural interventions to modify dietary fat, fruit and vegetable intake: a review of the evidence. Preventative Medicine 2002;35:25‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bland 1997

- Bland JM, Kerry SM. Statistical notes. Trials randomised in clusters. BMJ 1997;315(7108):600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boissel 1999

- Boissel JP, Cucherat M, Li W, Chatellier G, Gueyffier F, Buyse M, et al. The problem of therapeutic efficacy indices. 3. Comparison of the indices and their use. Therapie 1999;54(4):405‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 1999

- Brown S, Birtwistle J. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 1999;29(3):697‐701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brunner 2007

- Brunner EJ, Rees K, Ward K, Burke M, Thorogood M. Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002128.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carpenter 1994

- Carpenter WT, Buchannan RW. Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 1994;330:681‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chafetz 2008

- Chafetz L, White M, Collins‐Bride G, Cooper B, Nickens J. Clinical trial of wellness training: health promotion for severely mentally ill adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2008;196(6):475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daumit 2005

- Daumit GL, Goldberg RW, Anthony C, Dickerson F. Physical activity patterns in adults with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2005;193:641‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Hert 2006

- Hert MA, Winkel R, Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, Scheen A, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic medication. Schizophrenia Research 2006;83(1):87‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2000

- Deeks J. Issues in the selection for meta‐analyses of binary data. Proceedings of the 8th International Cochrane Colloquium; 2000 Oct 25‐28; Cape Town. Cape Town: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Department of Health 2005

- Department of Health. Choosing a better diet. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4105356 (accessed 5 September 2011).

Divine 1992

- Divine GW, Brown JT, Frazier LM. The unit of analysis error in studies about physicians' patient care behaviour. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1992;7(6):623‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donner 2002

- Donner A, Klar N. Issues in the meta‐analysis of cluster randomised trials. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21(19):2971‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Davey SG, Scheider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315(7109):629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elbourne 2002

- Elbourne D, Altman DG, Higgins JP, Curtin F, Worthington HV, Vail A. Meta‐analyses involving cross‐over trials: methodological issues. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):140‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 2005

- Evans S, Newton R, Higgins S. Nutritional intervention to prevent weight gain in patients commenced on olanzapine: a randomized controlled trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2005;39(6):479‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Filek 2006

- Filik R, Sipos A, Kehoe PG, Burns T, Cooper SJ. The cardiovascular and respiratory health of people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2006;113:298‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Furukawa 2006

- Furukawa TA, Barbui C, Cipriani A, Brambilla P, Watanabe N. Imputing missing standard deviations in meta‐analyses can provide accurate results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2006;59(7):7‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goff 2005

- Goff DC, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP. A comparison of ten‐year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophrenia Research 2005;80:45‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Green 2000

- Green A, Patel J, Goisman R. Weight gain from novel antipsychotics drugs: need for action. General Hospital Psychiatry 2000;22:224‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gulliford 1999

- Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, Chinn S. Components of variance and intraclass correlations for the design of community‐based surveys and intervention studies: data from the Health Survey for England 1994. American Journal of Epidemiology 1999;149(9):876‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heimberg 1995

- Heimberg C, Gallacher F, Gur RC, Gur RE. Diet and gender moderate clozapine‐related weight gain. Human Psychopharmacology 1995;10:367. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analysis. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (editors). In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hooper 2003

- Hooper L, Griffiths E, Abrahams C, Alexander W, Atkins S, Atkinson G. Dietetic guidelines: diet in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2003;17:337‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Huxley 2004

- Huxley RR, Lean M, Crozier A, John JH, Neil HAW. Effect of dietary advice to increase fruit and vegetable consumption on plasma flavonol concentrations: results from a randomized controlled intervention trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2004;58:288‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Irving 2006

- Irving CB, Mumby‐Croft R, Joy LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001257.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jenkins 2008

- Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, McKeown‐Essen G, Josse RG, Silverberg J. Effect of a low‐glycaemic index or a high‐cereal fibre diet on type 2 diabetes. Journal of American Medical Association 2008;300(23):2742‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Joshipura 2001

- Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001;134:1106‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kay 1986

- Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi‐Health Systems, 1986. [Google Scholar]

Laursen 2011

- Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophrenia Research 2011;131:101‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leon 2006

- Leon AC, Mallinckrodt CH, Chuang‐Stein C, Archibald DG, Archer GE, Chartier K. Attrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: methodological issues in psychopharmacology. Biological Psychiatry 2006;59(11):1001‐5. [PUBMED: 16905632] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leucht 2005a

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. Clinical implications of brief psychiatric rating scale scores. British Journal of Psychiatry 2005;187:366‐71. [PUBMED: 16199797] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leucht 2005b

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. What does the PANSS mean?. Schizophrenia Research 2005;79(2‐3):231‐8. [PUBMED: 15982856] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leucht 2007a

- Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2007;116:317‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marshall 2000

- Marshall M, Lockwood A, Bradley C, Adams C, Joy C, Fenton M. Unpublished rating scales: a major source of bias in randomised controlled trials. American Journal of Psychiatry 2000;176:249‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCreadie 2003

- McCreadie RG, Scottish Schizophrenia Lifestyle Group. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. British Journal of Psychiatry 2003;183:534‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]