Abstract

Objective

To estimate whether gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy was associated with improved survival compared to standard gynecologic regimens for women with ovarian mucinous carcinoma.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with ovarian mucinous carcinoma who received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy at two academic centers. Demographic and clinical information was abstracted from the medical records. Gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy contained 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, irinotecan, or oxaliplatin. Gynecologic regimens included standard carboplatin or cisplatin. Bevacizumab treatment was allowed in both groups. Summary statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics; Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator was used to compare survival outcomes.

Results

Fifty-two patients received either gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy (n=26; 50%) or a standard gynecologic regimen (n=26; 50%). Three-quarters of tumors were early-stage (I or II), 68% grade 1 or 2 and 88% of patients had no gross residual disease after surgery. Patients receiving gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy were more likely to receive bevacizumab (50% vs. 4%; P < .001), but there were no other differences in clinical or demographic characteristics. Unadjusted overall survival analyses showed that gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy was associated with better overall survival (HR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.8), as were early stage tumors and having no gross residual disease.

Conclusion

Gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab was associated with improved survival and should be considered in patients with ovarian mucinous carcinoma requiring adjuvant therapy.

Précis

Gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy is associated with improved survival in ovarian mucinous carcinoma when compared to standard gynecologic regimens.

INTRODUCTION

Mucinous carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of epithelial ovarian cancer. Although initial estimates were higher, more recent data suggest this subtype accounts for only about 2–3% of new epithelial ovarian cancer cases [1, 2]. Ovarian mucinous carcinoma is usually diagnosed at an early stage, is often found in the background of a borderline tumor and the diagnosis is particularly challenging as pathologic findings can be mimicked by gastrointestinal metastases [3–5].

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines currently recommend either observation or consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage IC disease (preoperative or intraoperative rupture, or positive cytology in pelvic washings), but favor treatment for stage II-IV with either gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy (i.e., for colon cancer) or a gynecologic ovarian cancer regimen [8]. Patients with advanced ovarian mucinous carcinoma tend to be more resistant to standard chemotherapy and have a worse prognosis compared to other epithelial subtypes [4, 9–13]. Currently, most of the limited data guiding decisions about adjuvant treatment is extrapolated from clinical trials of epithelial ovarian carcinoma in which mucinous tumors account for a very small proportion [14–19]. The histologic similarity to primary gastrointestinal tumors has led some investigators to hypothesize that ovarian mucinous carcinomas may respond better to non-gynecologic regimens [20].

The collaborative network GOG-241 randomized controlled trial was designed to test this hypothesis by comparing the gastrointestinal regimen of oxaliplatin and capecitabine to the standard gynecologic combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Poor accrual led to early closure. Moreover, of the patients with central review of their surgical specimens by a gynecologic pathologist, more than half were determined to be of non-gynecologic origin [5]. The question of which adjuvant chemotherapy regimen should be recommended for primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma remains unanswered and is unlikely to be resolved in a prospective manner. We sought to review our own institutions’ data to estimate whether the use of gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy was associated with a difference in survival compared with the use of a traditional gynecologic regimen.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both institutions.

Patients were eligible if they were treated at either institution during the period from January 1994 through December 2018. Patients had to have undergone primary surgical management and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. All pathology material was reviewed by gynecologic pathologists. A rigorous macroscopic and microscopic examination was performed to confirm an ovarian primary. If necessary, ancillary tests such as immunohistochemical stains and in situ hybridization for high risk human papillomavirus were obtained. A thorough clinical correlation (re-review of clinical findings, personal history, imaging studies and endoscopic examination) was obtained in those cases where the pathology examination could not determine with certainty an ovarian origin. The diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma was made using the criteria proposed by Riopel and Kurman [3]. Patients were considered to have received a gastrointestinal regimen if their chemotherapy included 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, oxaliplatin, or irinotecan as these are considered off-label in patients with primary ovarian cancer. Our clinical practice is to inform patients of this off-label use and to counsel them on the rationale for this recommendation at the time of treatment counseling. Patients were considered to have received a gynecologic regimen if they received a carboplatin- or cisplatin-containing regimen and did not receive any of the aforementioned gastrointestinal chemotherapy agents. Patients in both groups were allowed to have received bevacizumab. Patients who received hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy as primary treatment were excluded.

All data were abstracted from the electronic medical record and entered into the secure Research Electronic Data Capture database [21]. Institutional databases were used to identify patients with mucinous ovarian cancer on pathology review. Data for these institutional databases were abstracted from the electronic medical record and entered retrospectively by trainees at each institution. A senior gynecologic oncologist from each institution (ANF and MF) provided oversight and reviewed a random sample of the mucinous ovarian cancer patients in the databases who had received chemotherapy. No systematic errors were identified.

Summary statistics were used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Progression-free survival and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan and Meier product-limit estimator and were planned to be modeled via Cox proportional hazards regression if appropriate. Progression-free survival was measured from the date of surgery to the date of last clinic visit, date of first recurrence/progression, or date of death, whichever was earliest. Disease status outcomes were censored at date of the last clinic visit. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgery to the date of death or date of last contact, whichever was earliest. Due to the exploratory nature of our analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP version 15.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Fifty-two patients were included in this study. Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. The majority of patients had stage I disease (59%); only 24% had stage III or IV disease. Ninety percent of patients with stage I or II disease had surgical staging with an omentectomy with or without lymphadenectomy and 88% of patients had no gross residual disease after surgery.Of the patients with stage I disease, four patients in the gastrointestinal chemotherapy group and four patients in the gynecologic chemotherapy group had stage IA tumors. Of these, reasons cited for receiving chemotherapy included having a tumor with a high grade histologic component, suspected advanced disease based on imaging, unconfirmed rupture at the time of cystectomy, and a report of positive washings. Sixty-eight percent of patients had grade 1 or 2 tumors. Fifty-six percent of patients had ovarian mucinous carcinomas in the background of a borderline tumor.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by gastrointestinal and gynecologic regimens*

| Gastrointestinal-type Chemotherapy (n = 26) | Gynecologic Regimen (n = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 52) | P Value | ||

| Mean age ± SD, y | 45 ± 12 | 44 ± 12 | 45 ± 13 | 0.85 |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 28 (8) | 28 (7.58) | 27 (7.94) | 0.25 |

| Histologic grade | 0.93 | |||

| 1 | 12 (30) | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | |

| 2 | 15 (38) | 8 (40) | 7 (35) | |

| 3 | 13 (33) | 6 (30) | 7 (35) | |

| Unknown | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| Associated borderline tumor | 0.77 | |||

| Absent | 21 (44) | 10 (42) | 11 (46) | |

| Present | 27 (56) | 14 (58) | 13 (54) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Tumor debulking status | 0.35 | |||

| No gross residual | 43 (88) | 21 (88) | 22 (88) | |

| Optimal (< 1 cm residual) | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Suboptimal | 4 (8) | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| FIGO stage | 0.59 | |||

| I | 30 (59) | 16 (62) | 14 (56) | |

| II | 9 (18) | 4 (15) | 5 (20) | |

| III | 10 (20) | 4 (15) | 6 (24) | |

| IV | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||

| Bevacizumab | <0.001 | |||

| No | 38 (73) | 13 (50) | 25 (96) | |

| Yes | 14 (27) | 13 (50) | 1 (4) |

Y, years; BMI, body mass index; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Data are number of patients (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Half of patients received a standard gynecologic regimen, while the other 50% received gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy (Table 2). The median number of cycles of adjuvant therapy received in both the gastrointestinal regimen group and the gynecologic regimen group was six. Patients receiving gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy were much more likely to have concurrent bevacizumab (50% compared to 4% for gynecologic regimens; P < .001).

Table 2:

Adjuvant chemotherapy regimens

| Number of Patients | |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Capecitabine + oxaliplatin | 17 |

| 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin | 6 |

| Capecitabine + carboplatin + paclitaxel | 1 |

| Capecitabine alone | 1 |

| Capecitabine + oxaliplatin (1 cycle), changed to 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin | 1 |

| Gynecologic | |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel | 21 |

| Cisplatin + paclitaxel | 1 |

| Carboplatin + cyclophosphamide | 2 |

| Carboplatin alone | 2 |

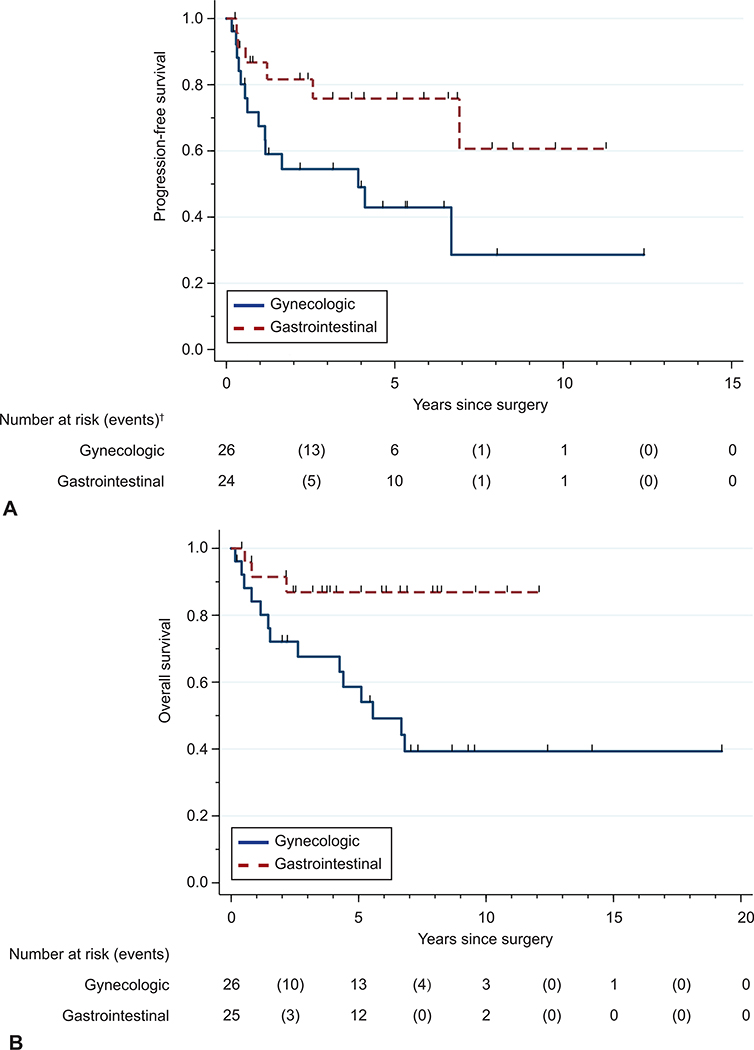

Suboptimal tumor debulking (larger than 1-cm residual tumor implants) was associated with worse progression-free survival (HR 16.3, 95% CI 4.3–62.3) and overall survival (HR 5.5, 95% CI 1.8–17.5; Table 3 and 4) compared to a complete resection. The presence of stage III or IV disease at diagnosis was also associated with worse progression-free survival (HR 6.5, 95% CI 2.3–18.1) and overall survival (HR 5.4, 95% CI 1.7–17.2). The use of gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy was associated with improved progression-free survival (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.1–0.97) and overall survival (HR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.8) compared with the use of a gynecologic regimen (Figure 1). There was no statistically significant difference in progression-free survival or overall survival associated with the use of bevacizumab. Because of the small number of events in this study, we were unable to perform multivariable analyses for progression-free or overall survival.

Table 3.

Univariable progression-free survival*

| Characteristic | N | Events | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery, y | 50 | 20 | 1.0 (0.97–1.04) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 44 | 15 | 1.0 (0.95–1.08) |

| Grade | |||

| 1 (Ref) | 12 | 4 | Ref |

| 2 | 14 | 6 | 1.5 (0.4–5.4) |

| 3 | 13 | 6 | 2.6 (0.7–9.3) |

| Associated borderline tumor | |||

| Absent (Ref) | 21 | 10 | Ref |

| Present | 26 | 8 | 0.6 (0.2–1.5) |

| Tumor debulking status | |||

| No gross residual (Ref) | 42 | 14 | Ref |

| Optimal (< 1 cm residual) | 2 | 1 | 9.0 (0.9–86.5) |

| Suboptimal | 4 | 4 | 16.3 (4.3–62.3) |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I (Ref) | 30 | 7 | Ref |

| II | 9 | 4 | 2.1 (0.6–7.0) |

| III or IV | 10 | 8 | 6.5 (2.3–18.1) |

| Chemotherapy regimen type | |||

| Gynecologic (Ref) | 26 | 14 | Ref |

| Gastrointestinal | 26 | 6 | 0.4 (0.1–0.97) |

| Bevacizumab | |||

| No (Ref) | 37 | 17 | Ref |

| Yes | 13 | 3 | 0.5 (0.1–1.7) |

Y, years; BMI, body mass index; Ref, reference; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

50 patients had data available for progression-free survival.

Table 4.

Univariable overall survival*

| Characteristic | N | Events | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery, y | 51 | 17 | 1.0 (0.98–1.06) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 45 | 12 | 1.0 (0.94–1.09) |

| Grade | |||

| 1 (Ref) | 12 | 2 | Ref |

| 2 | 15 | 5 | 2.5 (0.5–13.1) |

| 3 | 13 | 6 | 3.8 (0.8–19.0) |

| Associated borderline tumor | |||

| Absent (Ref) | 21 | 7 | Ref |

| Present | 27 | 8 | 1.0 (0.4–2.8) |

| Tumor debulking status | |||

| No gross residual (Ref) | 43 | 11 | Ref |

| Optimal (< 1 cm residual) | 2 | 1 | 16.4 (1.6–164.4) |

| Suboptimal | 4 | 4 | 5.5 (1.8–17.5) |

| FIGO stage | |||

| I (Ref) | 30 | 5 | Ref |

| II | 9 | 4 | 2.8 (0.7–10.4) |

| III or IV | 11 | 7 | 5.4 (1.7–17.2) |

| Chemotherapy regimen type | |||

| Gynecologic (Ref) | 26 | 14 | Ref |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 | 3 | 0.2 (0.1–0.8) |

| Bevacizumab | |||

| No (Ref) | 37 | 14 | Ref |

| Yes | 14 | 3 | 0.6 (0.2–2.0) |

Y, years; BMI, body mass index; Ref, reference; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

51 patients had data available for overall survival.

Figure 1.

Progression-free (A) and overall (B) survival stratified by gastrointestinal and gynecologic chemotherapy regimens.* Log-rank P value: progression-free survival (P=.04); overall survival (P=.01). *50 and 51 patients had data available for progression-free and overall survival, respectively. †At 0, 5, 10, and 15 years, the number of patients at risk are plotted, and the number of events that occur between these years are noted in parentheses.

Due to the disparity in use of bevacizumab between patients who received gynecologic regimens and those who received gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy, we performed an exploratory analysis to evaluate whether differences in outcomes were potentially due to the use of bevacizumab. Because of the small number of patients who received bevacizumab with a gynecologic regimen, we excluded the subset of patients who received any bevacizumab. Among the patients who did not receive bevacizumab, patients who received gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy had better overall survival (median 6.7 years vs. not reached for gastrointestinal regimen, P = .04) but not progression-free survival (median 4.1 years vs. not reached for gastrointestinal regimen, P = .15) compared with patients who received gynecologic regimens.

DISCUSSION

Patients with mucinous carcinomas truly originating in the ovary who require postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy may benefit from the use of gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy based on our exploratory findings. Previous efforts to conduct a more rigorous prospective comparison were abandoned due to the rarity of this tumor and are unlikely to be repeated in the near future. Although our sample size was too limited to conduct a multivariable analysis, there was insufficient evidence of any differences in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics between the gastrointestinal and gynecologic treatment groups to account for the observed survival differences.

The role of bevacizumab for primary ovarian mucinous carcinomas is unclear. We observed a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving bevacizumab in the gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy group, likely because it had been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with standard chemotherapy in 2004. In contrast, concurrent bevacizumab during adjuvant therapy for primary ovarian cancer was only approved in 2018. Since the differences in overall survival between gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy and gynecologic regimens were observed even in the subgroup of patients who did not receive bevacizumab, we cannot conclude whether bevacizumab use alone has any benefit in this population.

One of the strengths of this study was the relatively large number of patients with ovarian mucinous carcinomas, a rare tumor type. The extent of clinical information available and the relatively long follow-up times in both chemotherapy groups add to the value of these data. Furthermore, because one of the most important limitations of the GOG-241 trial was that 22 of 40 patients were ultimately found to have a non-ovarian primary tumor, the importance of the gynecologic pathology review in our study cannot be overstated. Given that the demographics in our cohort are similar to prior studies of patients with ovarian mucinous carcinoma, our results are likely generalizable to patients being treated at other academic centers across the country, and may also be generalizable to those treated in non-referral centers.

This study also has limitations. First, the study was retrospective, and the allocation of patients to treatment regimens was not random. Thus, inherent bias may exist as to which patients were treated with each regimen. Second, the study included patients treated over a period of 20 years, and practice patterns certainly changed during that time. However, the rarity of ovarian mucinous carcinomas means that relatively few patients with this type of cancer are treated each year, even at large referral centers, and thus a long study period was needed to ensure a large enough cohort to permit evaluation of our study questions. Third, the vast majority of the patients in our study had stage I disease. Although this was unsurprising given that most patients with mucinous ovarian cancer have early-stage disease at diagnosis [1], it means our data were largely based on outcomes of patients who did not have metastatic disease at diagnosis. Fourth, this study only evaluated chemotherapy regimens that were administered for first line treatment, and thus no conclusions can be made about the utility of chemotherapy choice at recurrence or the effects of treatment crossover. Last, our study sample was still modest overall, and there may not have been enough power to detect differences in some of our analyses. We also had a small number of events, likely because of the large number of patients with stage I disease. For this reason, our univariable survival analyses were exploratory in nature and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Nevertheless, these results can be considered to be hypothesis-generating and provide data to support the use of alternative regimens for a rare ovarian cancer subtype that has historically had poor response to traditional chemotherapy.

Although GOG-241 did not complete accrual, that study increased awareness about the possible use of gastrointestinal regimens in ovarian mucinous carcinoma and influenced a change in the chemotherapy prescribing patterns of many physicians at our institutions. On the basis of the data reported here, we believe patients with newly diagnosed high-risk stage I and all stage II-IV ovarian mucinous carcinomas should be counseled toward a gastrointestinal regimen with or without bevacizumab. Since most gynecologic oncologists will have little experience with the gastrointestinal-type chemotherapy regimens, collaboration with medical oncology colleagues may increase our own familiarity with these agents.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Katherine C. Kurnit disclosed receiving an GOG Foundation Young Investigator Travel Award (2018). She and Michael Frumovitz disclosed that this article discusses the following off-label drugs for ovarian cancer: Capecitabine, Oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and Irinotecan. Anil K. Sood disclosed receiving money paid to him from Merck and Kiyatec. Money was paid to his institution from M-Trap (research funding). He is a shareholder in BioPath. David M. Gershenson disclosed receiving Royalties from Elsevier and UpToDate for serving as editor or author for work unrelated to this study. He has a Consulting agreement with Genetech for work unrelated to this study. He also has Equity interests in managed accounts: Celgene, Johnson & Johnson, Biogen. He disclosed that related this this article, drugs described in GI regimens are commercially available and listed in NCCN guidelines for treatment of mucinous carcinoma of ovary but not FDA approved for this indication. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA016672, which supports the Clinical Trials Support Resource.

The authors thank Ms. Stephanie Deming for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kobel M, et al. , Differences in tumor type in low-stage versus high-stage ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2010. 29(3): p. 203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman JD, et al. , The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2004. 23(1): p. 41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riopel MA, Ronnett BM, and Kurman RJ, Evaluation of diagnostic criteria and behavior of ovarian intestinal-type mucinous tumors: atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors and intraepithelial, microinvasive, invasive, and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol, 1999. 23(6): p. 617–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaino RJ, et al. , Advanced stage mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary is both rare and highly lethal: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer, 2011. 117(3): p. 554–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore M, et al. , An international, phase III randomized trial in patients with mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC/GOG 0241) with long-term follow-up: and experience of conducting a clinical trial in a rare gynecological tumor. Gynecol Oncol, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salgado-Ceballos I, et al. , Is lymphadenectomy necessary in mucinous ovarian cancer? A single institution experience. Int J Surg, 2017. 41: p. 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmeler KM, et al. , Prevalence of lymph node metastasis in primary mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol, 2010. 116(2 Pt 1): p. 269–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Network, N.C.C. Ovarian Cancer (Version 1.2019). 2019. August 31, 2019]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf.

- 9.Hess V, et al. , Mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: a separate entity requiring specific treatment. J Clin Oncol, 2004. 22(6): p. 1040–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabuk E, et al. , Comparison of advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer and serous epithelial ovarian cancer with regard to chemosensitivity and survival outcome: a matched case-control study. J Gynecol Oncol, 2013. 24(2): p. 160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung YS, et al. , Outcomes of non-high grade serous carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Korean gynecologic oncology group study (OV 1708). BMC Cancer, 2019. 19(1): p. 341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons M, et al. , Survival of Patients With Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma and Ovarian Metastases: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2015. 25(7): p. 1208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firat Cuylan Z, et al. , Comparison of stage III mucinous and serous ovarian cancer: a case-control study. J Ovarian Res, 2018. 11(1): p. 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire WP, et al. , Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med, 1996. 334(1): p. 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccart MJ, et al. , Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2000. 92(9): p. 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muggia FM, et al. , Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol, 2000. 18(1): p. 106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bookman MA, et al. , Evaluation of new platinum-based treatment regimens in advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Phase III Trial of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Clin Oncol, 2009. 27(9): p. 1419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burger RA, et al. , Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(26): p. 2473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oza AM, et al. , Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16(8): p. 928–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frumovitz M, et al. , Unmasking the complexities of mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol, 2010. 117(3): p. 491–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, et al. , Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): p. 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell J, et al. , Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol, 2006. 102(3): p. 432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gresham GK, et al. , Characteristics and trends of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health between 2005 and 2015. Clin Trials, 2018. 15(1): p. 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auner V, et al. , KRAS mutation analysis in ovarian samples using a high sensitivity biochip assay. BMC Cancer, 2009. 9: p. 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gemignani ML, et al. , Role of KRAS and BRAF gene mutations in mucinous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol, 2003. 90(2): p. 378–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]