ABSTRACT

Anti-tumor immune response and the prognosis of tumor are the results of competition between stimulatory and inhibitory checkpoints. Except for upregulating inhibitory checkpoints, lowering some immune accelerating molecules to convert an immunostimulatory microenvironment into an immunodormant one through “decelerating the accelerator” might be another effective immune escape pattern. 4-1BBL is a classical transmembrane costimulatory molecule involving in antitumor immune responses. In contrast, we demonstrated that 4-1BBL is predominantly localized in the nuclei of cancer cells in colon cancer specimens and is positively correlated with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and a lower survival ratio. Furthermore, the nuclear localization of 4-1BBL was also ascertained in vitro. 4-1BBL knockout (KO) arrests the proliferation and impaired the migration and invasion ability of colon cancer cells in vitro and retarded tumor growth in vivo. 4-1BBL KO increased the accumulation of Gsk3β in the nuclei of colon cancer cells and consequently decreased the expression of Wnt pathway target genes and thus alter tumor biological behavior. We hypothesized that unlike membrane-expressed 4-1BBL, which stimulates the 4-1BB signaling of antitumor cytotoxic T cells, the nuclear-localized 4-1BBL could facilitate the malignant behavior of colon cancer cells by circumventing antitumor signaling and driving some key oncotropic signal pathway in the nucleus. Nuclear-localized 4-1BBL might be an indicator of colon cancer malignancy and serve as a promising target of immunotherapy.

KEYWORDS: Colon cancer, costimulatory molecule, 4-1BBL, nuclear localization, prognosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide [1]. Anti-tumor immunity is influenced by a complex set of tumor microenvironmental factors that govern the strength and timing of host against tumor reaction which will eventually be critical for the initiation [2], growth, invasion, and metastasis of cancer [3]. Studies are focusing on these factors as immune profiles that predict responses to immunotherapy and also serve as potential therapeutic targets as well [4]. A series of reports revealed that costimulatory molecules and their signaling are involved in the sculpture of tumor microenvironment (TME), as they mediate mutual modulation between tumor cells and their microenvironment in the pathological process of cancer [5]. In colorectal cancer, some costimulatory molecules could be used to complement the histopathological staging as valuable diagnostic or prognostic indicators [6–8], and also act as promising therapeutic targets [9,10].

Costimulatory molecule CD137 (4-1BB, TNF-receptor superfamily 9) is a surface glycoprotein of the TNFR family, which can be induced on a variety of leukocyte subsets, such as activated T cells and natural killer (NK) cells [11]. The ligand of CD137 (CD137L, 4-1BBL) is expressed on the membrane of antigen-presenting cells, including monocytes, activated macrophages, and dendritic cells [12,13]. With the ligation of 4-1BBL, it was found that 4-1BB signaling inhibited activation induced cell death, and enhanced proliferation and effector functions by mediating polyubiquitination-mediated signals via tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 2 [11]. In TME, 4-1BB are expressed precisely on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), showing a strong response against tumor antigens [14]. And more importantly, it is appreciated that 4-1BB signaling can break and reverse established anergy in cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and also contribute to restore the functionality of exhausted CD8 + T cells [15].

Tumorigenesis is always accompanied by the accumulation of alterations, which can provide a selective advantage to cancers cells by adopting features that enable them to active escape detection and killing of the immune system [16]. To create an immunosuppressive microenvironment, the immune checkpoint molecules CTLA4 and PD-1 are abducted by tumor cells to restrain T-cell-mediated immunity. Blocking these checkpoints as one of the effective therapy by “suppressing the suppressor” have garnered the most attention. Accordingly, except for upregulating immune checkpoints, lowering membrane expression of some immune accelerating molecules might be another effective immune escape pattern through “decelerating the accelerator” of anti-tumor responses.

In our study, we detected the nuclear localization of 4-1BBL molecule in colon cancer cells and tissues. Nuclear-localized 4-1BBL contributed to colon cancer cell proliferation and migration and correlated to the poor prognosis. Thus, except transmembrane and soluble patterns of expression, an alternative expression way of 4-1BBL was revealed. We hypothesized that unlike membrane-expressed 4-1BBL, which may stimulate the 4-1BB signaling of antitumor cytotoxic T cells in the tumor microenvironment, the nuclear-localized 4-1BBL should facilitate the malignant behavior of colon cancer cells by circumventing antitumor signaling and driving some key oncotropic signal pathway in the nuclear.

Hence, in this study, we discussed the biological effects and the underlying mechanisms of nuclear 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells. Meanwhile, we observed 4-1BBL expression on clinical colon cancer specimens and analyzed its clinical relevance.

Results

TMA and IHC analysis of 4-1BBL protein expression and localization in a cohort of 89 colon cancer patient tissues and their correlation with clinicopathologic features and survival

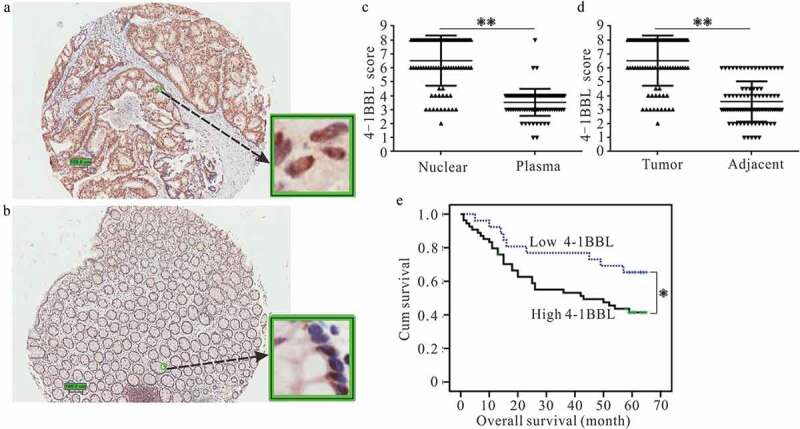

To investigate the expression and localization of 4-1BBL in colon cancer tissues, we conducted immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for 4-1BBL on a colon cancer TMA containing 90 pairs of colon cancer specimens and the corresponding tumor adjacent tissues. A pair of tumor and tumor adjacent tissue was outlined as they were severely broken, and the samples from the other 89 colon cancer patients were further analyzed.

The IHC staining of 4-1BBL in representative colon cancer samples is shown in Figure 1(a,b). Interestingly, 4-1BBL molecules were not only expressed in the colon cancer tissue but also dominantly localized the nuclei of cancer cells (Figure 1(a,c)).

Figure 1.

Tissue microarrays assay analyzed the expression of 4-1BBL in colon cancer tissues and the prognostic significance of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer patients. Representative immunohistochemistry images show the expression and subcellular distribution of 4-1BBL in (a) tumor tissues or (b) tumor adjacent tissues. (c) The level of nuclear 4-1BBL is higher than that of cytoplasmic 4-1BBL in the tumor tissues. (d) The nuclear 4-1BBL is higher in tumor tissues than that in tumor adjacent tissues. (e) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis according to the nuclear localized 4-1BBL levels in 89 patients with colon cancer (log-rank test). Probability of survival of patients: low expression of 4-1BBL, n= 25; high expression of 4-1BBL, n = 64. *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01.

According to the criteria described in the Materials and methods section, the high expression of nuclear localized 4-1BBL was found in the tumor tissues, as compared with that of the tumor-adjacent tissues (Figure 1(d); P < 0.01).

A correlation analysis revealed that the high expression of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL was positively correlated with colon cancer lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05; Table 1) and a more advanced clinical stage (P < 0.01; Table 1). A Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the survival ratio of colon cancer patients with a high expression of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL was poor when compared with that of patients with a low-expression level of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL (P = 0.047 [P < 0.05]; Figure 1(e)).

Table 1.

Correlation between the clinicopathologic variables and expression of nuclear localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer.

| Nuclear 4-1BBL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | Low expression | High expression | P value ∆ | |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | .8653 | |||

| ≤ 67.2 | 45 | 13 | 32 | |

| > 67.2 | 44 | 12 | 32 | |

| Gender | .3310 | |||

| Male | 50 | 12 | 38 | |

| Female | 39 | 13 | 26 | |

| Histological grade (WHO) | .8927 | |||

| G1/G2 | 72 | 20 | 52 | |

| G3 | 17 | 5 | 12 | |

| pT status | .0390 | |||

| T1-T2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| T3-T4 | 84 | 21 | 63 | |

| pN status | .0052 | |||

| 0 | 43 | 18 | 25 | |

| 1 | 46 | 7 | 39 | |

| pM status | .3542 | |||

| pM0 | 84 | 25 | 59 | |

| PM1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Clinical stage | .0034 | |||

| Ⅰ/Ⅱ | 42 | 18 | 24 | |

| Ⅲ/Ⅳ | 47 | 7 | 40 | |

∆Chi-square test.

4-1BBL is expressed and localized in the nuclei of colon cancer cell lines

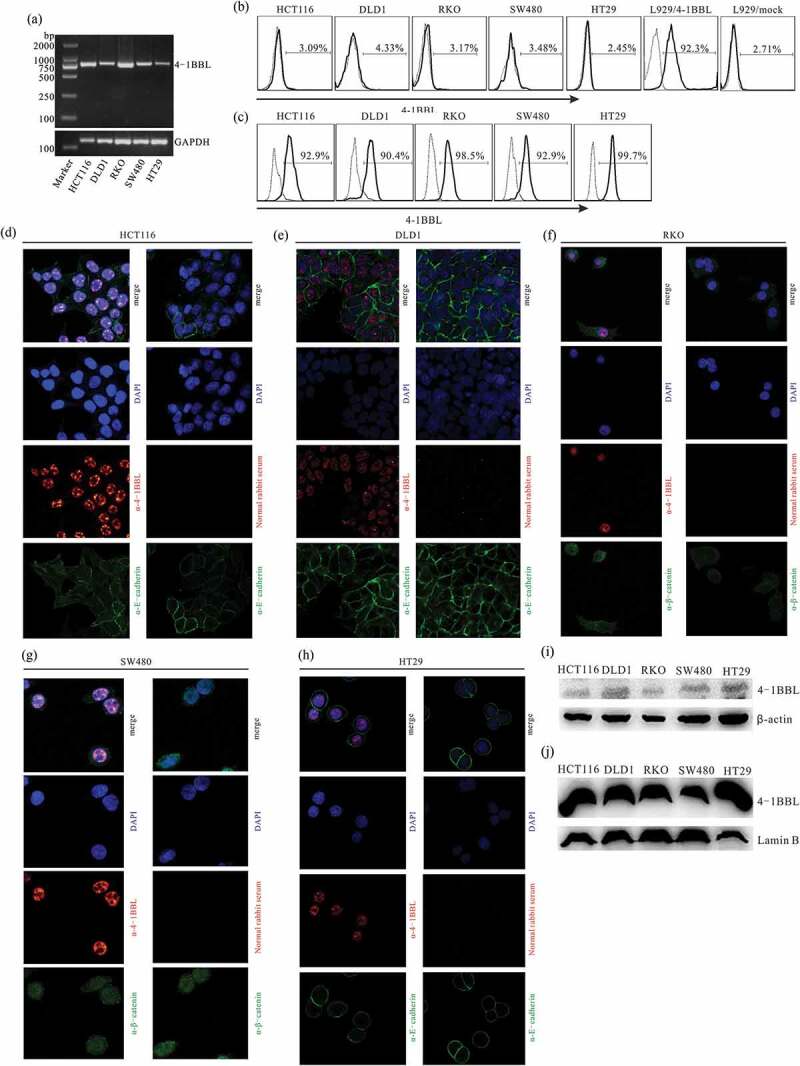

To confirm that the costimulatory molecule 4-1BBL possessed the existing form, nuclear localization, we examined the 4-1BBL mRNA expression level in five colon cancer cell lines using reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. As shown in Figure 2(a), 4-1BBL expressed in all five colon cancer cell lines. We then sequenced all the RT-PCR products and found that there was no mutation when compared with the 4-1BBL open-reading frame (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_003811.3, data not shown). Consequently, we analyzed 4-1BBL protein expression by immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry. It was found that 4-1BBL molecules were not detected on the cell surface of colon cancer cells (Figure 2(b)). Interestingly, 4-1BBL molecules were residing within the cells, as identified by intracellular staining and flow cytometry (Figure 2(c)). To determine the exact location of 4-1BBL molecules, immunostaining, and laser confocal microscopy were performed. The 4-1BBL molecules were dominantly localized in nuclei of colon cancer cells (Figure 2(d–h)). This distribution pattern of 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells was further confirmed by subcellular protein fractionation and Western blot assay (Figure 2(i,j)).

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells. (a) RT-PCR analysis of 4-1BBL expression in colon cancer cell lines. (b) Immunostaining and flow cytometry analyze membrane 4-1BBL of colon cancer cells. L929/4-1BB cells, 4-1BBL gene-transfected L929 cells, were used as membrane 4-1BBL positive cells. L929/mock cells were used as 4-1BBL negative cells. The solid-line histogram illustrates 4-1BBL antibody staining, while the dotted-line histogram showcases the Ig isotype control staining. (c) Intracellular staining and flow cytometry analyze 4-1BBL expression in colon cancer cell lines. (d-h) Confocal immunofluorescent microscopy disclosed a nuclear localization of 4-1BBL in colon cancer cell lines. Rabbit anti-4-1BBL primary antibody and Alexa Flour 633 conjugated anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody were used (red). Mouse anti-E-cadherin or anti-β-catenin primary antibody and Alexa Flour 488 conjugated anti-mouse antibody were used to exhibit cellular shape (green). DAPI staining to indicate the cellular nuclear (blue). (i), (j) Western blot analysis of 4-1BBL subcellular distribution in colon cancer cell lines. I, membrane and cytoplasmic proteins extracted from colon cancer cells. J, nuclear proteins isolated from colon cancer cells. Lamin B, nuclear envelope marker.

Construction of 4-1BBL KO HCT116 and DLD1 cells

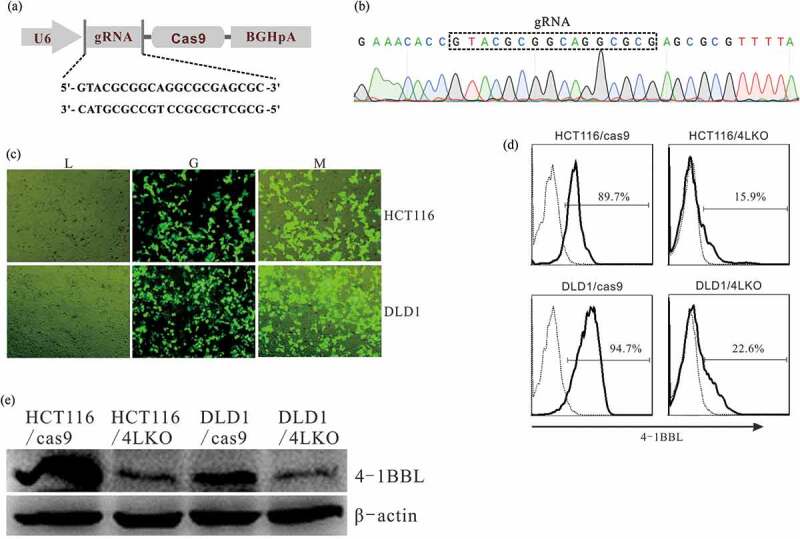

4-1BBL KO cells were developed in the HCT116 and DLD1 cell lines using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Figure 3(a,b)). GFP expression confirmed the PGK1.2/4LKO vector was successfully introduced into some of the HCT116 or DLD1 cells (Figure 3(c)). The 4-1BBL KO cells, referred to as HCT116/4LKO and DLD1/4LKO, were selected with intracellular staining and flow cytometry (Figure 3(d)) and further confirmed with Western blot assay (Figure 3(e)). The PGK1.2 vector-transfected HCT116 and DLD1 cells, referred to as HCT116/cas9 and DLD1/cas9, were established as controls.

Figure 3.

Deletion of 4-1BBL expression by CRISPR/cas9 system. (a) Schematic illustration of the construction of pGK1.2 vector inserted with gRNA that targeting 4-1BBL. (b) The gRNA insertion was verified with gene sequencing. (c) GFP expression in HCT116 and DLD1 cells transfected with PGK1.2/4LKO vector was observed by using the fluorescence microscope. (d) Intracellular staining and flow cytometry analyze 4-1BBL expression in colon cancer cell lines. (e) Western blot analysis of 4-1BBL expression in colon cancer cell lines. Total proteins extracted from colon cancer cells. HCT116/cas9, HCT116 cells transfected with PGK1.2 vector. DLD1/cas9, DLD1 cells transfected with PGK1.2 vector. HCT116/4LKO, 4-1BBL deleted HCT116 cells. DLD1/4LKO, 4-1BBL deleted DLD1 cells.

Nuclear 4-1BBL KO regulated the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCT116 and DLD1 cells

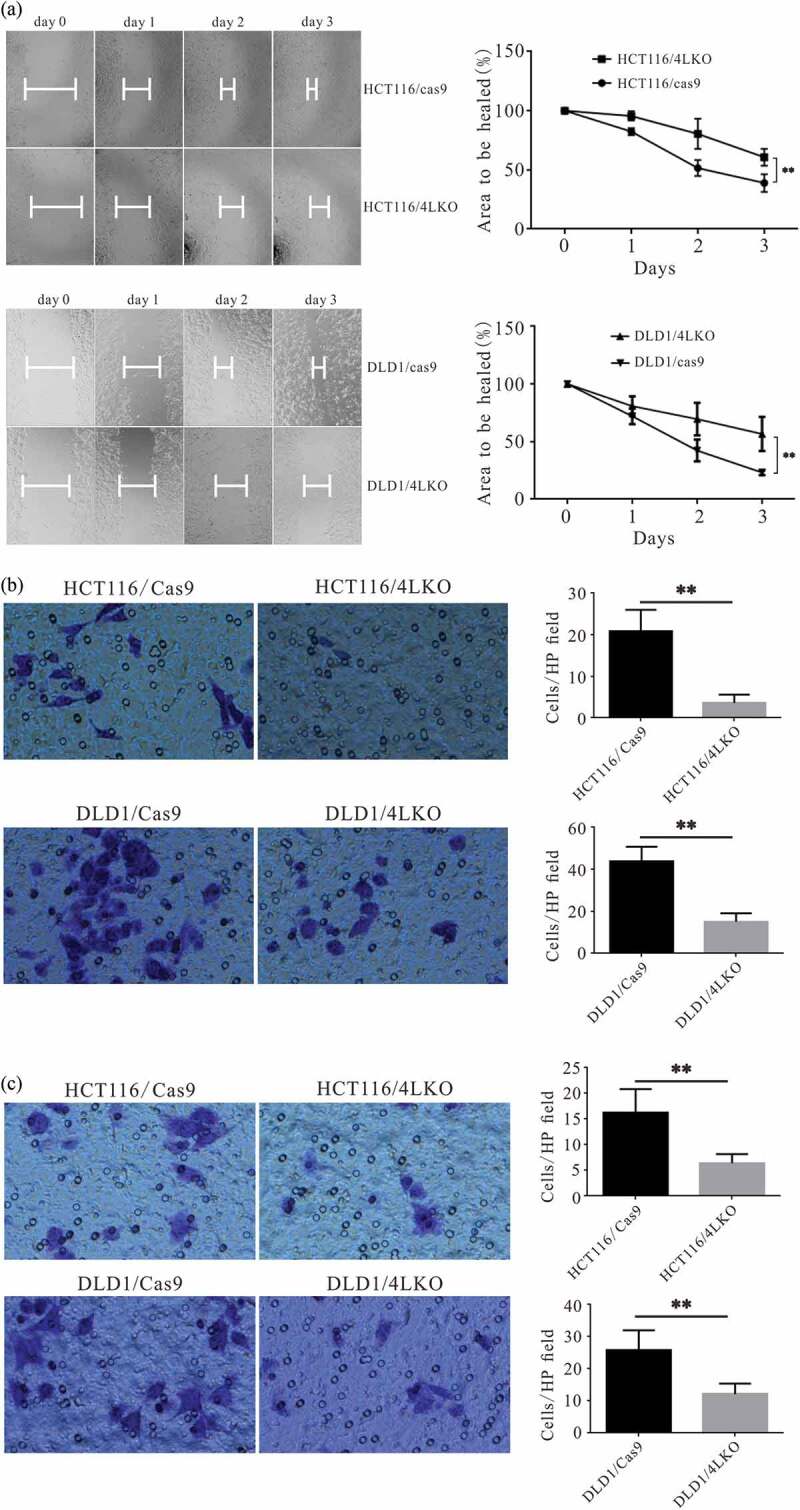

The DT of HCT116/4LKO (28.39 ± 0.09 h) was extended when compared with that of HCT116/cas9 (23.06 ± 0.23 h; P< 0.01). Similarly, the DT of DLD1/4LKO (29.81 ± 0.54 h) was increased when compared with that of DLD1/cas9 (22.98 ± 0.12 h; P < 0.01). The wound-healing assay showed that 4-1BBL KO slowed the proliferation of HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Figure 4(a,b)). The migration ability (Figure 4(c,d); P < 0.01) and invasion ability (Figure 4(e,f); P < 0.01) of HCT116 and DLD1 were significantly decreased after 4-1BBL KO.

Figure 4.

Deletion of 4-1BBL inhibited the migration and invasiveness of colon cancer cells in vitro. (a) Wound healing assay showed that the area to be healed of HCT116/4LKO group was than that of HCT116/4LKO group, as well as that of DLD1/4LKO group vs DLD1/cas9 group. (b) The migration ability of colon cancer cells was determined by transwell assay. (c) The invasive ability of colon cancer cells was demonstrated by matrigel invasion assay. **, P < 0.01.

Gsk3β (the Wnt pathway regulator) nuclear accumulation is involved in the biological effects of nuclear 4-1BBL in HCT116 and DLD1 cells

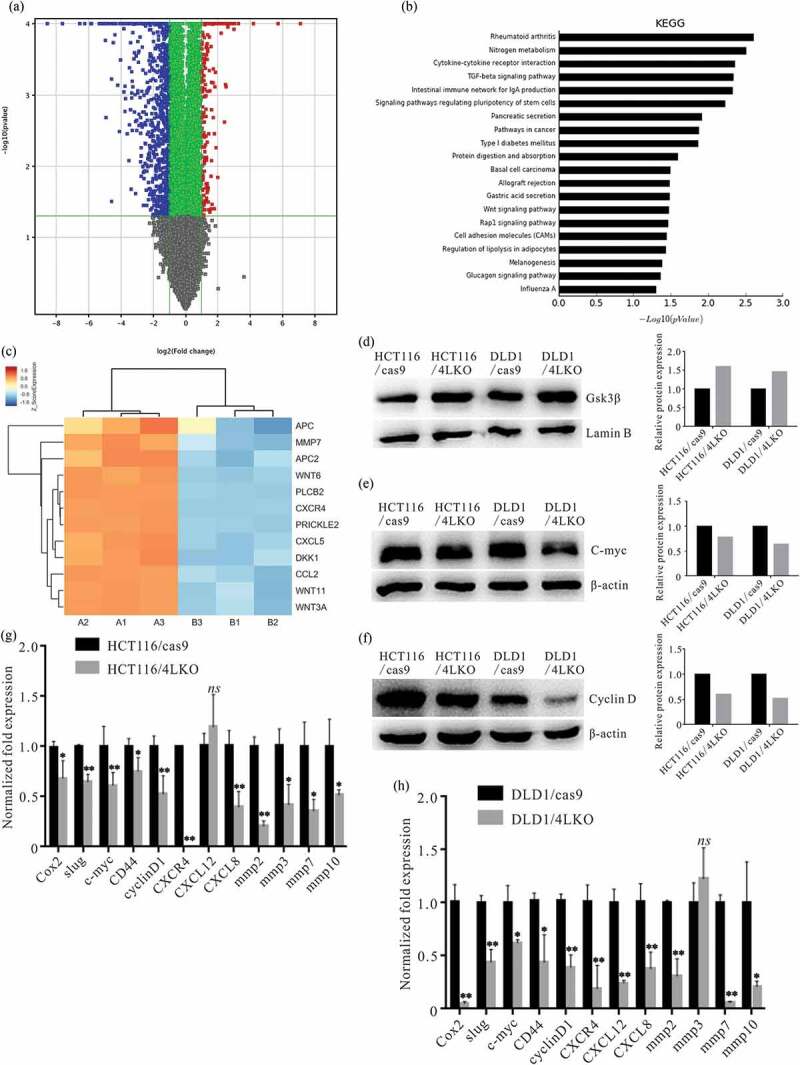

To determine which singling pathway is involved in the biological functions of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells, the mRNA expression profile of HCT116/4LKO and HCT116/cas9 cells was analyzed with a GeneChip assay. KEGG analysis suggested that the Wnt pathway was downregulated in HCT116/4LKO cells compare with the HCT116/cas9 (Figure 5(a–c)).

Figure 5.

4-1BBL deletion increased nuclear Gsk3β accumulation and altered the Wnt pathway-related molecules. (a) HCT116/cas9 and HCT116/4LKO cells were subjected to gene expression microarray. Differential expression genes of HCT116/cas9 vs HCT116/4LKO cells. (b) Screening for the signaling pathways associated with 4-1BBL KO by the KEGG database. (c) The expression of Wnt pathway-related genes is presented as a heat map. A1, B1, and C1 are the triplicate HCT116/cas9 samples. B1, B2, and B3 are the triplicate HCT116/4LKO samples. Western blot assay analyzed the (d) Nuclear Gsk3β accumulation, (e) cytoplasmic C-myc and (f) cytoplasmic Cyclin D1 levels in 4-1BBL deleted colon cancer cells. (g), (h) Realtime PCR assay demonstrated the alteration of Wnt/β-catenin pathway-related genes in 4-1BBL deleted colon cancer cells. *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01. ns, P ≥ 0.05.

The Western blot assay revealed that levels of nuclear Gsk3β (the Wnt pathway regulator) were increased in HCT116/4LKO and DLD1/4LKO cells (Figure 5(d)). The Western blot assay also demonstrated that 4-1BBL KO led to the downregulation of cytoplasmic C-myc and Cyclin D1 in HCT116/4LKO and HCT116/cas9 cells (Figure 5(e,f)).

Real-time PCR assay was introduced to analyze the expression levels of Wnt pathway-related genes. It was revealed that 4-1BBL KO decreased slug, c-myc, CD44, cyclinD1, CXCR4, CXCL8, MMP2, MMP3, MMP7, and MMP10 expression in HCT116/4LKO cells (Figure 5(g)), and it decreased slug, c-myc, CD44, cyclinD1, CXCR4, CXCL12, CXCL8, MMP2, MMP3, MMP7, and MMP10 expression in DLD1/4LKO cells (Figure 5(h)).

Nuclear 4-1BBL regulated the in vivo growth of HCT116 and DLD1 cells in tumor-bearing mouse models

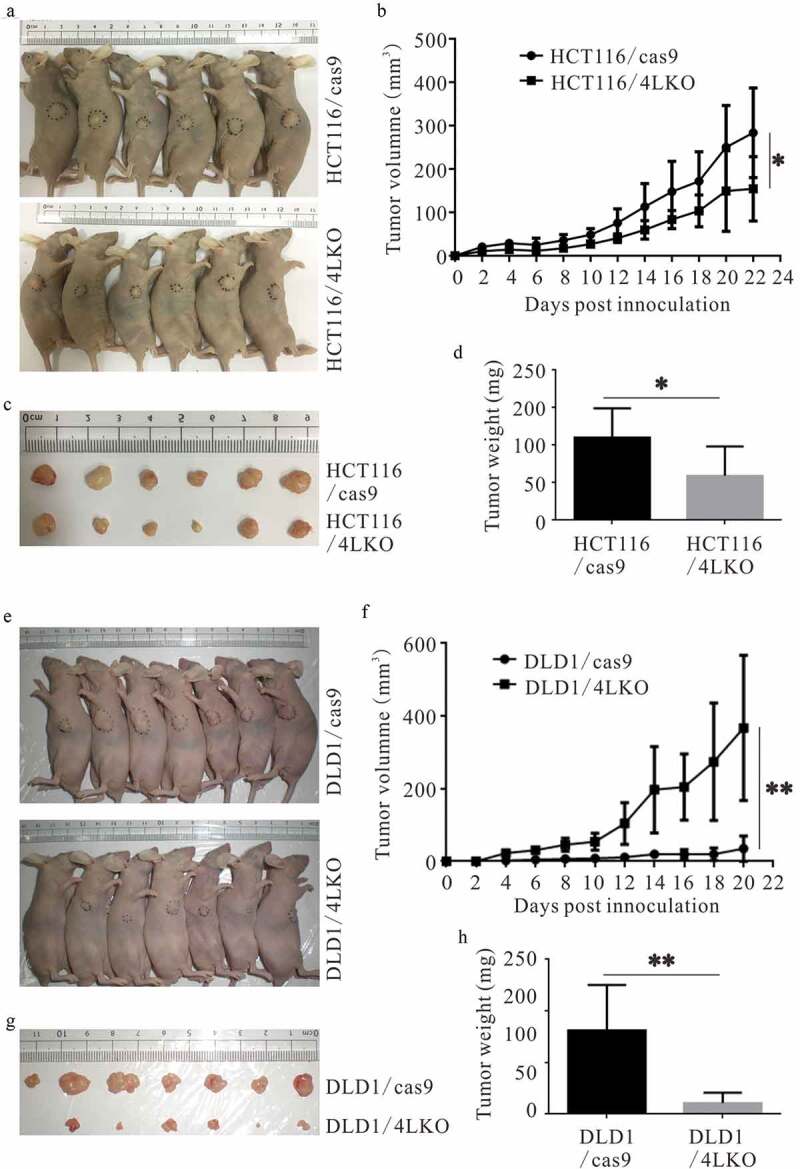

To further verify the biological effect of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells, HCT116/4LKO or DLD1/4LKO cells were implanted subcutaneously into the flank of nude mice, whereas HCT116/cas9 or DLD1/cas9 cells were injected into the opposite flank. Compared with the HCT116/cas9 group, the tumor masses, and tumor growth of the HCT116/4LKO group were significantly reduced (Figure 6(a,d)). Consistently, when compared with the DLD1/cas9 group, the tumor masses and tumor growth of DLD1/4LKO cells were dramatically decreased (Figure 6(e–h)). In all, 4-1BBL KO slowed the HCT116 cell and DLD1 cell growth to varying degrees in vivo.

Figure 6.

4-1BBL deletion prevents the growth of colon cancer cells in vivo. (a-d) 4-1BBL deletion inhibited the HCT116 cell growth in nude mice. (e-h) 4-1BBL deletion decreased the DLD1 cell growth in nude mice. *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01.

Discussion

Costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules are critical factors that modulate the delicate immunological balance between the cancer cell and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and influence the pathological progress and prognosis of cancer patients. Anti-tumor immune response and the prognosis of the host is a result of competition between inhibitory and stimulatory checkpoints [17]. Upregulation of inhibitory checkpoints CTLA-4 and PD-L1 dysregulates cellular immunity and accelerates the evolutionary fitness making the tumor cells to be more adaptive to their microenvironment [18]. However, although this milestone discovery of blocking these “brakes” has been translated into clinical success, only a fraction of patients can benefit from it with durable responses and long-term survival [19]. They only represent the tip of the iceberg of potential targets that can serve to improve anti-tumor responses [20]. Generally speaking, the ultimate principle of the tumor is to convert an immunostimulatory microenvironment into an immunodormant one to escape from an immune attack. As opposed to the upregulation of the co-inhibitory pathways that attenuate the immune reaction, downregulation of co-stimulatory molecules should also be the philosophy of tumor to anergy immune responses.

4-1BB is an inducible co-stimulatory receptor expressed on T cells, including TILs, as well as NK cells and APCs. Ligation to 4-1BBL delivers a costimulatory signal to T cells, necessary for their full activation, proliferation, and memory. Although 4-1BBL is structurally a type II transmembrane protein [12], we demonstrated for the first time that 4-1BBL molecules were predominantly localized in the nuclei of cancer cells by colon cancer tissue array and immunohistochemistry assay. Moreover, high expression levels of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL are positively correlated with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and clinical stage. The overall survival of patients with high levels of nuclear-localized 4-BBL is significantly lower than that with lower levels. Furthermore, the nuclear localization of 4-1BBL found by tissue array was also ascertained ex vivo by flow cytometry, western blot, and laser confocal microscopy. Zhang et al. reported that B7-H4 molecules are cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling proteins, owing to their nuclear-localizing signals (NLS) in renal cancer cells [21]. We sequenced the RT-PCR products from HCT116, DLD1, RKO, SW480, and HT29 colon cancer cell lines only to find that 4-1BBL does not contain a classical NLS. Although NLS conventionally involves in the nuclear trafficking, it has become increasingly apparent, however, that distinct alternative pathways for nuclear transport exist and are relatively abundant. Especially in the tumor microenvironment, the aberrant regulation of nuclear transport in transformation and oncogenesis has become increasingly evident. Ghebeh et al. found that B7-H1 was translocated from the membrane to the nucleus of breast cancer cells to counteract apoptosis induced by Doxorubicin. Our finding implies that some unknown mechanisms from the cancer cell itself, or from the tumor microenvironment, might force the 4-1BBL molecules to be redistributed in the nuclei of cancer cells. We speculated that whatever mechanism involves in 4-1BBL nuclear trafficking, as a keynote accelerator to immune activation, the nuclear localization of the surface molecule could at least decelerate the T cell co-stimulation and thus be conducive to immune escape. One of the most important approaches of cancer immunotherapy is to convert an immunosuppressive tumor into an immunostimulatory one. In this way, “removing the brakes” via blocking inhibitory checkpoint and “stepping on the accelerator” via co-stimulation are of equal importance.

To further explore the biological function of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells, 4-1BBL KO colon cell lines were established. 4-1BBL KO retarded the proliferation and impaired the migration and invasion ability of colon cancer cells in vitro. It is supposed that nuclear 4-1BBL might participate in the malignant behavior of colon cancer. Subsequently, GeneChip expression array analysis suggested that the Wnt pathway might be involved in the biological function of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL molecules. We found that Gsk3β molecules had been accumulating in the nuclei following the 4-1BBL deletion in colon cancer cells. Caspi et al. reported that nuclear GSK3β could inhibit the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in a β-catenin phosphorylation-independent manner in colorectal cancer cells [22]. Our western blot assay demonstrated that c-myc and cyclin D1, the classical Wnt pathway target gene [23,24] was decreased in 4-1BBL KO cells. Real-time PCR identified a series of target genes of the Wnt pathway [25–29] were influenced following 4-1BBL KO. Concretely speaking, the downregulation of c-myc and cyclin D1, which mediate the proliferation of colon cancer cells [30], might contribute to inhibition of cancer cell growth. The impairment of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and CXCL8, which engaged not only in the proliferation, but also the chemotaxis of many types of cancer cells [31,32] is essentially in consistent with the impairment of the migration ability of 4-1BBL KO cells. Furthermore, 4-1BBL KO leads to the decreases of MMPs that play important roles in the invasion and migration of colon cancers and ultimately mediates their negative prognosis [33–35]. These results give an unsophisticated account of the invasion assay in vitro. Thus, the nuclear Gsk3β-associated Wnt pathway may mediate the biological function of nuclear-localized 4-1BBL in colon cancer cells. In addition, 4-1BBL KO significantly inhibited the growth of colon cancer cells in tumor-bearing nude mice, further confirming that nuclear-localized 4-1BBL plays important roles in malignant biological behaviors.

The strong association between nuclear 4-1BBL and the poor outcome of colon cancer, combined with aberrant activation of the Wnt pathway implies that subcellular localization of the protein might be an indicator of colon cancer malignancy and a promising molecular marker in immunotherapy, enable us to make therapeutic procedures on a personalized basis.

Materials and methods

Reagents, antibodies, and flow cytometry

Fluorochrome-labeled antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For the analysis of surface molecules, the cells were stained with antibody in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). To detect intracellular cytokines, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using Fix/Perm Buffer (eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stained for intracellular cytokines. Flow cytometry data were acquired on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Cell lines and cell culture conditions

Colon cancer cell lines HCT116, DLD1, SW480, HT-29, and RKO were originally purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Tissue microarray (TMA) assay for 4-1BBL expression on colon cancer tissues

Primary colon adenocarcinoma samples were used for the construction of a TMA. The samples on the tissue chip (product number: HCol-Ade180Sur-03; Shanghai Biochip Co., Ltd., Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) were from 90 patients with colon adenocarcinoma. Matched pairs of 1.5 mm diameter cylinders from two different areas, the center of the tumor tissue, and the sample adjacent to the tumor, were included in each case to ensure reproducibility and homogenous staining of the slides. Sections of 4 μm thickness were mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides for subsequent staining with a rabbit anti-human 4-1BBL antibody (Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA) following a two-step protocol, as described in our previous report [36]. Normal rabbit serum (Novus Biologicals) was used as the control for rabbit anti-human 4-1BBL staining.

Evaluation of immunohistochemical variables

The stained tissue chip was scanned with an Aperio Pathological Scanning System (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and assessed independently by two pathologists. Staining intensity was assessed as 0 (none), 1–2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). The percentage of stained cells was assessed as 0 (none), 1 (<10%), 2 (10–30%), 3 (30–80%), or 4 (>80%). A staining score (values 0–12) was calculated as the product of staining intensity multiplied by the percentage of stained cells. Each patient was represented by the mean value from the tumor and the adjacent tissue, respectively.

Immunodetection with confocal microscopy

Colon cancer cell lines HCT116, DLD1, SW480, HT29, and RKO were cultured on a chamber slide (NUNC) and the cells were grown until they reached 70–80% confluence. Then, a 4% paraformaldehyde fixation solution was poured onto the cells and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After being rinsed and washed with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After being blocked with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA for 45 min at room temperature, the cells were incubated with a rabbit anti-human 4-1BBL primary antibody for 30 min. Then, after being twice washed with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100, the cells were incubated with DyLight 633 conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ImmunoReagents, Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. After they were twice washed with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100, the cells were incubated with mouse anti-human E-Cadherin (Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK) or mouse anti-human β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) primary antibody for 30 min. Then, after being washed twice, the cells were stained with DyLight 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were then washed twice and the nuclei were stained with DAPI for 10 s. After being washed twice, the cells were covered with a coverslip by adding 50 μL of anti-fade medium and subsequently sealed. Normal rabbit serum (Novus Biologicals) was used as the control for rabbit anti-human 4-1BBL staining. All images were observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica Microsystems).

Generation of 4-1BBL gene KO colon cancer cell lines

Based on the human 4-1BBL gene sequence and its chromosome location, guide RNAs (gRNAs) were searched from a CRISPR design platform maintained by the Zhang lab (http://crispr.mit.edu/). The gRNA oligonucleotides, targeting the sequence of TACGCGGCAGGCGCGAGCGCGGG, located at exon 2 of human 4-1BBL cDNA (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_003811.3), were formed by annealing at room temperature and then cloned into the CRISPR/Cas9 vector PGK1.2 with a GFP marker (Genloci Biotechnologies Inc., Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China). The positive recombinant vector was transduced into HCT116 cells and DLD1 cells according the instruction of X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) 24 h after transfection; then, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) and seeded on 96-well plates with limited dilution. Twenty-four hours later, puromycin at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL for DLD1 cells and 2 μg/mL for HCT116 cells was added into the culture medium. Then, 72 h later, the culture medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 containing 10% (FBS). After the clones formed, the cells were analyzed for 4-1BBL expression by intracellular staining, flow cytometry, and Western blot assay.

Calculation doubling time of colon cancer cells

To calculate the doubling time [34] of colon cancer cells, 100 μL/well of colon cancer cells, suspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS at a concentration of 2 × 104/mL, were seeded on a 96-well plate and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. At 24 h and 96 h, the cells were harvested for counting and their DT was calculated using the following equation:

DT = ∆t× lg2/(lgNt-lgN0), where N0 is the cell concentration at first counting, Nt is the cell concentration at final counting, and ∆t is the time interval between two counts.

Wound-healing assay

When the colon cancer cells reached 70–90% confluence, a single wound was scratched and photographed at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after incubation. The area to be healed was calculated as follows (%) = 100% × the distance of wound/the original distance of the wound. The experiment was performed for in triplicate.

Cell-invasion assay and cell-migration assay

After 24 h of starvation in RPMI 1640 without serum, the colon cancer cells were harvested and resuspended in RPMI 1640 without serum at a concentration of 5 × 105/mL. Then, 100 μL of colon cancer cells were seeded into an upper compartment with 8 μm cores (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), which was pre-coated with Matrigel (Corning Inc.) for cell-invasion assay and without Matrigel for cell-migration assay. Following that, 600 μL of RPMI 1640 with 20% serum was added in the lower compartment. After being incubated for 24 h, the penetrated cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde before stained with Crystal Violet Staining Solution (Beyotime, Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China), and quantified in five areas randomly selected per insert. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from isolated colon cancer cells using the Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was subject to reverse transcription using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio. Inc., Kusatsu, Japan), followed by conventional PCR or quantitative PCR analysis.

To quantify the genes of interest, cDNA samples were amplified in a qTower real-time PCR system (Analytik, Jena, Germany) with SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and specific primers (Table 2), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold changes in mRNA expression between treatments and controls were determined by the ∆CT method, as described [37]. Error bars on the plots represent the standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise noted. The data were normalized to a GAPDH reference. All primer syntheses and DNA sequencing were performed by Sangon Biotech Inc. (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China).

Table 2.

Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Gene name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| CD44 | CTCATGGATCTGAATCAGATGGA | ACTGCAATGCAAACTGCAAGA |

| cox2 | CAAATTGCTGGCAGGGTTGC | CTGCCTGCTCTGGTCAATGG |

| CXCL8 | TCTCTTGGCAGCCTTCCTGA | TTTCTGTGTTGGCGCAGTGT |

| CXCL12 | CAGATTGTAGCCCGGCTGAAG | CCCACGTCTTTGCCCTTTCA |

| CXCR4 | CCTGGCTTTCTTCGCCTGTT | AAAGCTAGGGCCTCGGTGAT |

| Cyclin D1 | CCGTCCATGCGGAAGATC | GACAGGAAGCGGTCCAGGTA |

| C-myc | CCCGCTTCTCTGAAAGGCTC | TCGTCGCAGTAGAAATACGGC |

| GAPDH | CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT | GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT |

| mmp2 | CCCATGAAGCCCTGTTCACC | CGGTCGTAGTCCTCAGTGGT |

| mmp3 | GCTCCCGAGGTTGGACCTAC | GTTTCACATCTTTTTTGAGGTCGTA |

| mmp7 | GGTCACCTACAGGATCGTATCATAT | CATCACTGCATTAGGATCAGAGGAA |

| mmp10 | CTCATGCCTACCCACCTGGA | GGCCAAGTTCATGAGCAGCA |

| Slug | GCCAAACTACAGCGAACTGGAC | CGCCCCAAAGATGAGGAGTAT |

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed with standard protocols using colon cancer cells. Rabbit anti-human 4-1BBL, rabbit anti-human lamin B (ProteinTech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA), rabbit anti-human C-myc polyclonal antibodies (Abcam plc), rabbit anti-human Cyclin D1, rabbit anti-human Gsk3β, and rabbit anti-human β-actin polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were used. Blots were washed three times in TBST for 30 min, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam plc) for 20 min, washed three times in TBST, and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence.

Establishment of tumor-bearing mice

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee at Soochow University. Nude mice were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center CAS (SLACCAS Laboratory Animal Inc., Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). To verify the roles of 4-1BBL in the growth of colon cancer cells in vivo, 2 × 106/site of HCT116/cas9 and HCT116/4LKO cells were injected subcutaneously into the bilateral flanks of nude mice. Then, 2 × 106/site of DLD1/cas9 and DLD1/4LKO were implanted into the nude mice with the same approach. Tumor growth was monitored every 2 d. Tumor size was assessed by measuring the largest perpendicular diameters and was recorded as the tumor volume, as follows: V = 1/6π × (length) × (width) × (width). The formed tumor masses were removed and weighed after the tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package (standard version 17.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The correlation between 4-1BBL expression and the clinicopathological features of CRC patients was analyzed using the χ2 test. For univariate survival analysis, survival curves were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method. The independent Student’s t-test was performed to analyze the statistical significance between two preselected groups. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant nos. 31370887 and 81373149]. Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation [grant no. QRX17205]. Fund for Digestive Diseases and Nutrition Research Key Laboratory of Suzhou [grant no. SZS201620]. Fund of Medical Youth Talent project of Jiangsu Province [grant no. QNRC2016241]. Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). Import Team of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Soochow Project Funding [grant no. SZYJTD201803].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Choi Y, Sateia HF, Peairs KS, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2017;44(1):34–44. DOI: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Choi CR, Bakir IA, Hart AL, et al. Clonal evolution of colorectal cancer in IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(4):218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Catalano V, Turdo A, Di Franco S, et al. Tumor and its microenvironment: a synergistic interplay. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(6 Pt B):522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bahrami A, Khazaei M, Hassanian SM, et al. Targeting the tumor microenvironment as a potential therapeutic approach in colorectal cancer: rational and progress. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(4):2928–2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sun J, Chen LJ, Zhang GB, et al. Clinical significance and regulation of the costimulatory molecule B7-H3 in human colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(8):1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bin Z, Guangbo Z, Yan G, et al. Overexpression of B7-H3 in CD133+ colorectal cancer cells is associated with cancer progression and survival in human patients. J Surg Res. 2014;188(2):396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Petty JK, He K, Corless CL, et al. Survival in human colorectal cancer correlates with expression of the T-cell costimulatory molecule OX-40 (CD134). Am J Surg. 2002;183(5):512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hua D, Sun J, Mao Y, et al. B7-H1 expression is associated with expansion of regulatory T cells in colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(9):971–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kohrt HE, Colevas AD, Houot R, et al. Targeting CD137 enhances the efficacy of cetuximab. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2668–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [10].Burris HA, Infante JR, Ansell SM, et al. Safety and activity of varlilumab, a novel and first-in-class agonist anti-CD27 antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):2028–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sanchez-Paulete AR, Labiano S, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, et al. Deciphering CD137 (4-1BB) signaling in T-cell costimulation for translation into successful cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(3):513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ju SW, Ju SG, Wang FM. et al. A functional anti-human 4-1BB ligand monoclonal antibody that enhances proliferation of monocytes by reverse signaling of 4-1BBL. Hybridoma Hybridomics. 2003;22(5):333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ju S, Ju S, Ge Y, et al. A novel approach to induce human DCs from monocytes by triggering 4-1BBL reverse signaling. Int Immunol. 2009;21(10):1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheuk AT, Mufti GJ, Guinn BA.. Role of 4-1BB:4-1BB ligand in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11(3):215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chester C, Sanmamed MF, Wang J, et al. Immunotherapy targeting 4-1BB: mechanistic rationale, clinical results, and future strategies. Blood. 2018;131(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541(7637):321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marin-Acevedo JA, Dholaria B, Soyano AE, et al. Next generation of immune checkpoint therapy in cancer: new developments and challenges. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lou YY, Diao LX, Cuentas ERP, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is associated with a distinct tumor microenvironment including elevation of inflammatory signals and multiple immune checkpoints in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(14):3630–3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sharpe AH, Pauken KE. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(3):153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161(2):205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang L, Wu H, Lu D, et al. The costimulatory molecule B7-H4 promote tumor progression and cell proliferation through translocating into nucleus. Oncogene. 2013;32(46):5347–5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Caspi M, Zilberberg A, Eldar-Finkelman H, et al. Nuclear GSK-3 beta inhibits the canonical Wnt signalling pathway in a beta-catenin phosphorylation-independent manner. Oncogene. 2008;27(25):3546–3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang X, Zhang X, Wang T, et al. MicroRNA-26a is a key regulon that inhibits progression and metastasis of c-Myc/EZH2 double high advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2018;426:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xu P, Dang YY, Wang LY, et al. Lgr4 is crucial for skin carcinogenesis by regulating MEK/ERK and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 2016;383(2):161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pandit H, Li Y, Li XY, et al. Enrichment of cancer stem cells via beta-catenin contributing to the tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lv YF, Dai HZ, Yan GN, et al. Downregulation of tumor suppressing STF cDNA 3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis of osteosarcoma by the Wnt/GSK-3 beta/beta-catenin/Snail signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;373(2):164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Choe Y, Pleasure SJ. Wnt signaling regulates intermediate precursor production in the postnatal dentate gyrus by regulating Cxcr4 expression. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34(6):502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Heijink IH, de Bruin HG, van den Berge M, et al. Role of aberrant WNT signalling in the airway epithelial response to cigarette smoke in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2013;68(8):709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hino M, Kamo M, Saito D, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces invasion ability of HSC-4 human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells through the Slug/Wnt-5b/MMP-10 signalling axis. J Biochem. 2016;159(6):631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yu JH, Liu D, Sun XJ, et al. CDX2 inhibits the proliferation and tumor formation of colon cancer cells by suppressing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling via transactivation of GSK-3 beta and Axin2 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Coniglio SJ. Role of Tumor-Derived Chemokines in Osteolytic Bone Metastasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sobolik T, Su YJ, Wells S, et al. CXCR4 drives the metastatic phenotype in breast cancer through induction of CXCR2 and activation of MEK and PI3K pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(5):566–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jagadish N, Parashar D, Gupta N, et al. A-kinase anchor protein 4 (AKAP4) a promising therapeutic target of colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Klupp F, Neumann L, Kahlert C, et al. Serum MMP7, MMP10 and MMP12 level as negative prognostic markers in colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang Q, Liu S, Parajuli KR, et al. Interleukin-17 promotes prostate cancer via MMP7-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2017;36(5):687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ge Y, Deng Y, Chen W, et al. Rspo1/LGR5 pathway promotes cervical cancer cell growth and is correlated with the high pathological grade. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9(9):9048–9057. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Xiang Y, Ma N, Wang D, et al. MiR-152 and miR-185 co-contribute to ovarian cancer cells cisplatin sensitivity by targeting DNMT1 directly: a novel epigenetic therapy independent of decitabine. Oncogene. 2014;33(3):378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]