Abstract

Estrogen is a key hormone involved in the development and homeostasis of several tissue types in both males and females. By binding estrogen receptors, estrogen regulates essential functions of gene expression, metabolism, cell growth, and proliferation by acting through cytoplasmic signaling pathways or activating transcription in the nucleus. However, disruption or dysregulation of estrogen activity has been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of many diseases. This review will expatiate on some of the unconventional roles of estrogen in homeostasis and disease.

Keywords: estrogen, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, diabetes, disease, cardiovascular disease

Steroids and steroid receptors

Steroid hormones are lipids that act as signaling molecules for steroid receptors. Steroids can be grouped into 2 classes: corticosteroids and sex steroids, and are further classified into 5 types according to the receptors they bind: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, androgens, estrogens, and progesterones (1). Steroid hormone nuclear receptors are transcription factors that modulate cellular activities through regulation of gene expression. In the classical steroid receptor signaling model, steroids cross the plasma membrane and bind to their receptors localized in the cytoplasm (2), which are often sequestered in an inactive conformation by heat shock proteins. Next, steroid-bound receptors undergo a conformational change that results in the dissociation of heat shock proteins, dimerization, translocation to the nucleus, and association with various coregulators (3). Then, the receptors or the coregulators will bind to specific sequences of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) called hormone response elements or specific DNA target sequences within or close to promoter regions. This drives changes in messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression, which typically leads to alterations in protein expression and, ultimately, cellular biology. The primary focus of this review will be on estrogen and its actions via estrogen receptors (ERs).

Estrogen and estrogen receptors

Estrogens are the primary female sex hormones involved in both reproductive and nonreproductive systems. Human estrogens include estrone, estriol, and 17β‐estradiol (estradiol or E2). Estradiol possesses the most potent estrogenic properties and thus will be the focus of this review. Estrogens play an essential role in the development and physiology of many organ systems, including the cardiovascular, reproductive, endocrine, respiratory, and nervous systems, to name a few (4). Estrogen action is controlled by 2 main types of ERs called ERα and ERβ, encoded by ESR1 and ESR2, respectively. ERα and ERβ share approximately 95% homology in their DNA-binding domains (5). However, their ligand-binding domains share only 56% of amino acid sequence identity, which differentiates their ligand affinities (5, 6). Thus, while estrogen can activate both receptors, the biological effects may be different due to these structural differences (7). ERα is expressed mainly in the mammary glands, uterus, ovary, bone, male reproductive organs, prostate, liver, and adipose tissues, while ERβ is found primarily in the uterus, pulmonary tissue, immune system, prostate, ovary, and colon (8, 9). Estradiol can act in 2 major ways via ERs: genomic (or nuclear) and nongenomic (or cytoplasmic) signaling. This leads to differences in cellular and molecular events, leading to gene expression changes. Genomic activity of estrogen is primarily mediated by the transcription factor action of ERs in the nucleus, while the nongenomic signaling is activated through cytosolic signal transduction pathways that initiate at the plasma membrane and will be described in the following section. In the genomic estrogen signaling pathway, once the ligand-bound receptors translocate to the nucleus, they act as transcription factors to increase or decrease gene transcription by direct binding of the receptors to estrogen response elements (EREs), as well as through ERE-independent promoter interactions (10). EREs have been identified in several gene promoters and regulatory regions; however, it has also been reported that more than one-third of human genes regulated by estrogen receptors do not contain EREs (11). Ultimately, estrogen-regulated gene products control autophagy, proliferation, apoptosis, survival, differentiation, and vasodilation under normal conditions, but can be dysregulated in diseases (3).

Unconventional Estrogen Signaling

Regulation of cytoplasmic signaling

Estrogen can rapidly activate signaling pathways in the cytoplasm within seconds or minutes by binding cytoplasmic or plasma membrane-associated receptors, such as ERα splice variants ER-36 and ER-46, ERβ, and G-protein–coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) (12). These ERs regulate plasma membrane ion channels and G-protein–coupled receptors and are able to propagate signal transduction through kinase signaling cascades. Our data (13) and work by other groups (14) indicate that estradiol activates kinase signaling in the cytoplasm independently of the genomic function of ERs. These kinase-mediated pathways include the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK)/p90 Ribosomal S6 Kinase (RSK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt (3). We and others have shown that estrogen rapidly and potently activates signaling by the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) (13, 15, 16), stimulating activation of mTORC1 in various estrogen-responsive tissues (17–19).

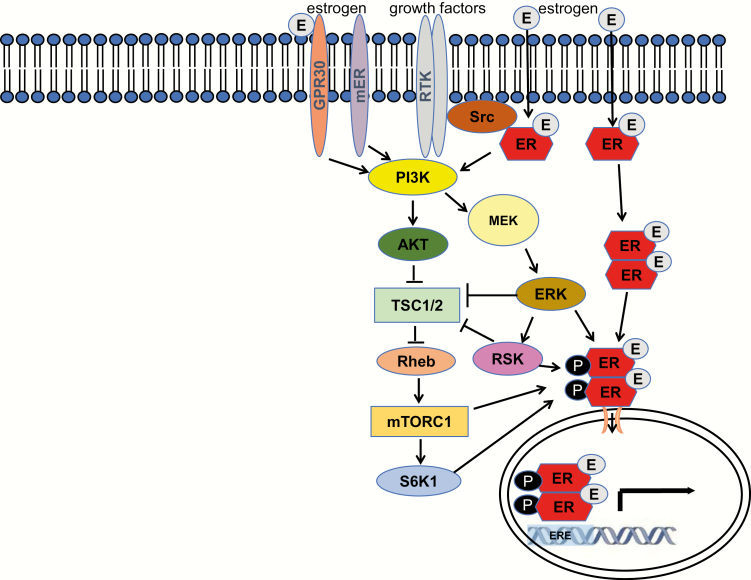

The action of estradiol via the cytoplasmic signaling pathway does not result in direct activation of transcription. Rather, ER complexes act through kinase signaling cascades that may ultimately activate effector transcription factors and initiate changes in gene expression. As depicted in Fig. 1, growth factor-stimulated kinases can also activate ERα, leading to multisite phosphorylation of the receptor and ligand-independent activation (20–23). ERα also promotes transcription of receptor tyrosine kinases, signaling adaptors, and a number of growth factor genes (14). Thus, activation of ERα by growth factor signaling is promoted in a feed-forward fashion.

Figure 1.

ERα signaling pathways. Estrogen receptor (ER) α can be activated by estrogen and growth factors to control transcription of target genes. Growth factors regulate kinase signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) to activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/p90 Ribosomal S6 Kinase (RSK), and mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)/40S Ribosomal S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) pathways. Estrogen-stimulated ERα can activate these pathways via Src. Plasma membrane-associated estrogen receptors (mER), GPR30 and ERα splice variants ER-36/ER-46 also activate intracellular signaling cascades.

Regulation of nuclear kinase signaling

Estradiol’s genomic activity is initiated by binding to ERα and ERβ in the cytoplasm, which causes receptor dissociation from inhibitory heat shock proteins, phosphorylation, dimerization, and translocation to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, they act as transcription factors to increase or decrease gene transcription by direct binding of the receptors to EREs (10). While EREs have been identified in several gene promoters and regulatory regions, it has been reported that more than one-third of human genes regulated by ERs do not contain ERE sequence elements (11). Previous studies, focused on understanding the cross-talk between ERα and MAPK signaling pathways, have described that estrogen-activated ERα colocalization with ERK2 in the nucleus leads to ER-mediated transcription of estrogen-dependent genes involved in cell proliferation (24, 25). Moreover, estrogen stimulates ERK2, which acts in concert with activated mTORC1 to enhance the transcription and expression of Fra1, a promoter of cell migration and invasion (18). A nuclear interaction between RSK2, a MAPK pathway effector, and ERα has also been described to promote a proneoplastic transcriptional network (26). We and others have also observed an interaction between mTORC1 and ERα (22, 27, 28). Thus, estrogenic activation of nuclear transcription involves the complexity of crosstalk between both the genomic and cytoplasmic signaling pathways.

Regulation of protein synthesis

Estrogen stimulation of protein synthesis was first observed in the 1960s, and since then has been studied in both normal homeostasis and in cancer. Translational control is a critical step in the regulation of gene expression, growth, and differentiation in the cell. Thus, aberrations in translational control are frequently observed in many diseases, specifically cancer (29). Translation initiation is the rate-limiting phase and is tightly regulated by signaling pathways such as MAPK, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and mTORC1. mTORC1 directly phosphorylates several proteins involved in translation, including translational inhibitors (the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding proteins [4E-BPs], and programmed cell death protein 4 [PDCD4]) and translational activators (the 40S ribosomal protein S6 kinases 1 and 2 [S6Ks] and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4B [eIF4B]) (30). 4E-BP phosphorylation by mTOR prevents its binding to eIF4E, allowing for the assembly of the eIF4F complex and cap-dependent mRNA translation (30). Several pieces of evidence implicate estrogen/ERα in regulation of protein synthesis. The p160 coactivator of ERα amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) was shown to activate protein synthesis in breast cancer cells (31). Estrogenic signaling via mTORC1 has also been depicted to activate global protein synthesis in mouse uteri (32), although this effect may be due to a combination of cytoplasmic and genomic signaling. Others observed mTOR binding to the C-terminal domain of the inhibitory translation initiation complex subunit eIF3F in mouse primary satellite cells (33, 34). Subsequently, we have demonstrated that estrogen activates the mTORC1 pathway to regulate translation by fine-tuning the levels of eIF3F, which enhances the assembly of the translation preinitiation complexes and protein synthesis (30). Thus, estrogen regulates gene expression not only at the level of transcriptional control but also by fine-tuning levels of protein synthesis of estrogenically regulated genes.

Unconventional Estrogen Signaling in Diseases

Alzheimer’s disease

The estrogen network plays a crucial role in the brain’s master regulatory system. Under its influence, the brain is able to respond at proper time points to regulate brain energy metabolism, such as in the ovarian-neural estrogen axis. Intracellular signaling, neural circuitry, and energy availability can all be impacted by changes in the availability of estrogen or its receptor network (35). In 2017, women accounted for about 60% of the 5.5 million Americans diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease (AD), an irreversible type of dementia that results in the decline of memory and thinking skills over time (36). However, despite this, the underlying biological mechanisms behind the increased sex bias in AD are still unknown. There exists preclinical evidence suggesting that a change in the brain’s bioenergetic system during the perimenopause to menopause transition (MT) could be a risk factor for AD in females, in addition to an apolipoprotein E-4 genotype (36, 37).

During MT, a decrease in estrogen levels leads to several changes, including shifts in protein expression, alterations in receptor degradation, epigenetic reconfigurations, and expression of ER splice variants (37). Neurologically, women undergoing MT typically experience a disruption in thermoregulation, sleep, and may even suffer from cognitive impairments, which are all estrogenically regulated processes (36). The brain compensates for decreased estrogen and reduced receptor activity during the MT, and in some women, this can lead to a different menopausal phenotype altogether as a result of altered estrogen-regulated neural networks (37, 38).

Glucose dysmetabolism is also typical in AD, which leads to reduced mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase activity in brain tissue in humans (36). In a study analyzing mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase activity in women during premenopause, perimenopause, and menopause, it was found that similarly to patients with AD, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women exhibited brain hypometabolism, while premenopausal woman did not (36). This, along with many other studies, solidifies the notion that sex-specific hormonal stages may contribute to an increased risk of AD in women, particularly during perimenopause and postmenopause. However, with all the evidence indicating the crucial role estrogen plays within neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, much remains to be learned about its specific genomic and nongenomic pathways in conjunction with the disease state.

Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by insulin resistance, elevated blood glucose, and reduced insulin secretion that result from interplay between genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors (39). As the global burden of DM is expected to increase to 4.4% of the human population by 2030, there is a pressing need for the development of new treatment methods (40). Understanding the role that ER signaling plays in glucose homeostasis is important for identifying potential therapeutic targets. Estrogen has been observed to mediate its effects in DM via classical interaction with nuclear ERα and ERβ as well as through extranuclear ERα and GPER (41). Estrogen was shown to modulate GLUT4 expression differentially via ERα and ERβ by studies evaluating ER-/- mice. Mice lacking ERα showed insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance in both males and females. Ovariectomy of ER-/- mice caused improvement in glucose metabolism and insulin response, which suggested a potential opposing action for ERβ. Both ERα and ERβ are expressed in skeletal muscle of mice, allowing for regulation of glucose homeostasis based on the ratio of ERα to ERβ in a specific tissue type. This discovery has opened the door for development of co-adjuvant therapies for DM that could selectively activate ERα and suppress ERβ in order to increase GLUT4 expression and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (42).

Estrogen acting via ERα has also been shown to protect pancreatic β-cells from apoptosis, a hallmark of advanced DM (43). β-cells are known to undergo death by apoptosis in response to oxidative stress caused by proinflammatory cytokines and chronically elevated blood glucose, conditions associated with DM. After exposure to oxidative stress, wild-type female mice showed no change in pancreatic islet structure, β-cell number, or insulin concentration, whereas male mice were susceptible to oxidative stress and showed a decrease in β-cell number and insulin concentration. In aromatase knockout mice, both male and female mice were equally susceptible to oxidative stress and β-cell apoptosis. In both wild-type and aromatase knockout mice, estrogen treatment had a protective effect against β-cell destruction in response to oxidative stress. Estrogen has also been shown to prevent β-cell apoptosis in response to oxidative stress, independently of the nuclear ER activity. Cultured islets were exposed to hydrogen peroxide to mimic oxidative stress and treated with estrogen or a membrane-impermeant estrogen conjugate, which resulted in similar protection from apoptosis after exposure to oxidative stress, indicating a potential role of extranuclear estrogenic signaling in β-cell protection (44).

Activation of the GPER also exhibits a protective effect in human islets against cytokine-induced apoptosis. Cultured human islets treated with estrogen and G-1 (a GPER agonist) prevented apoptosis of islet cells exposed to a mixture of cytokines in the presence of ERα and ERβ inhibitors. Estrogen and G-1 treatment also enhanced the secretion of insulin in islets from both diabetic and nondiabetic participants in the presence of 12mmol/L glucose concentration. These results suggest a therapeutic potential for drugs activating GPER (45).

Cardiovascular disease

According to the World Health Organization, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is currently the leading cause of death for both men and women globally. Clinical and animal studies have shown that CVD differs between males and females, and leads to more deaths in women than men each year since the mid-1980s, accounting for 50% of female deaths and 41% of male deaths (46–48). CVD incidence is lower in premenopausal women than in men over the age of 50 years. However, after menopause, CVD incidence in women surpasses that of men over the age of 50, which hints at a possible link between the decline of estrogen and cardiovascular integrity (47). This could be explained by estrogen’s ability to abrogate effects of catecholamines, such as decreasing norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction in perimenopausal women (49). Many studies, such as the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (49), have also analyzed the influence of hormone replacement therapy on CVD and demonstrated an increase in coronary heart disease in patients with ERα polymorphisms, specifically in postmenopausal women (49).

The fundamental reasons for these sex differences are certainly composite, but evidence suggests that estrogen and its receptors, ERα, ERβ, and GPER, play a significant role in CVD. ERs are located in different types of cardiac cells and play different functions within each (50). In cardiomyocytes, for example, it has been shown that estrogen stimulates the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase through a nongenomic mechanism whereby ERα localized to caveolae and noncaveolae rafts in endothelial cell membranes activates the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide production (51). Thus, estrogen’s nongenomic actions in vascular cells certainly play a significant cardioprotective role overall (52). ERβ distribution in vascular tissues is less characterized, but human endothelial cells synthesize ERβ, and blood vessels of nonhuman primates, mice, and rats express this receptor subtype as well (53, 54). Studies in mouse models have shown that overexpressed ERβ was primarily located in the nuclei of cardiomyocytes and in the cytoplasm, indicating a crucial cytoplasmic role of ERβ in cardiovascular development that requires further exploration (55).

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare lung disease characterized by proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells of unknown origin, metastasis via lymphatics to the lungs, and progressive cystic lung destruction (28, 56). LAM occurs primarily in women of childbearing age, supporting a role for estrogen in the development and progression of the disease. Many clinical and experimental observations also suggest that estrogen signaling plays a large role in LAM (57, 58). For example, LAM progression has been shown to correlate with increased estrogen levels during pregnancy or in women taking estrogen-containing hormone replacement therapy, and decline when estrogen levels are low, typically postmenopause (59).

LAM cells are characterized by inactivating mutations in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 1/2 genes, which encode for tumor suppressor proteins that, under homeostatic conditions, control cell growth through mTORC1 inhibition (56), providing rationale for use of mTOR inhibitors for treatment of the disease. Several pieces of evidence show that unconventional estrogen signaling plays a role in LAM pathogenesis. In a study conducted in ovariectomized mice with uterine-specific TSC2 deletion, progressive estrogen-dependent uterine enlargement and lung metastasis were observed, providing one of the best links between uterine-like smooth muscle cells and estrogen as a cause of LAM development (60). Interestingly, estrogen was able to stimulate mTORC1 in the absence of TSC2 in these cells, raising a question about the nature of the cytoplasmic signaling pathway from estrogen to mTORC1. Another study found that estrogen stimulation of cultured human TSC2-null cells caused cell growth that was mediated through the genomic and cytoplasmic MAPK pathways, resulting in mTORC1 activation (28). While mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for LAM treatment, some patients do not respond to treatment or experience side effects, limiting its overall effectiveness (61). Thus, the connection between estrogen, mTORC1, and LAM indicates that antiestrogen therapy may be effective in some instances of the disease.

Conclusions

Estrogen and its role in signaling via its receptors has emerged as an important node in multiple diseases and presents a potential therapeutic target. In addition to its canonical role in regulation of transcription, estrogen is a potent activator of cytoplasmic kinase signaling and protein synthesis. It is evident that estrogen signaling via both nuclear and cytoplasmic pathways is important in the normal physiology of multiple organ systems in both males and females, and that further elucidation of its mechanisms in maintaining homeostasis may provide a deeper understanding into pathogenesis of many diseases and subsequent identification of new therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs An Huang, Jerry Nadler, Jana Velíšková, and Michael Wolin (New York Medical College) for their constructive comments on this paper. We apologize to authors whose work was not described here due to space limitations.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- eIF

eukaryotic initiation factor

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ERE

estrogen response element

- GPER

G-protein–coupled estrogen receptor

- LAM

lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MT

menopause transition

- mTORC

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex

- TSC

tuberous sclerosis complex

Financial Support: National Institutes of Health grant R35-GM128675 (M.K.H.)

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Holst JP, Soldin OP, Guo T, Soldin SJ. Steroid hormones: relevance and measurement in the clinical laboratory. Clin Lab Med. 2004;24(1):105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levin ER, Hammes SR. Nuclear receptors outside the nucleus: extranuclear signalling by steroid receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(12):783–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkenfeld SR, Lin C, Frigo DE. Communication between genomic and non-genomic signaling events coordinate steroid hormone actions. Steroids. 2018;133:2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paterni I, Granchi C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Minutolo F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 2014;90:13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Bader M, Ford C, Al-Ayadhy B, Francis I. Analysis of estrogen receptor isoforms and variants in breast cancer cell lines. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2(3):537–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menazza S, Murphy E. The expanding complexity of estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2016;118(6):994–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ranganathan P, Nadig N, Nambiar S. Non-canonical estrogen signaling in endocrine resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paterni I, Granchi C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Minutolo F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 2014;90:13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee H-R, Kim T-H, Choi K-C. Functions and physiological roles of two types of estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, identified by estrogen receptor knockout mouse. Lab Anim Res. 2012;28(2):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holz MK. The role of S6K1 in ER-positive breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(17):3159–3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuentes N, Silveyra P.. Estrogen receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2019;116:135–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cui J, Shen Y, Li R. Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during aging: from periphery to brain. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(3):197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maruani DM, Spiegel TN, Harris EN, et al. Estrogenic regulation of S6K1 expression creates a positive regulatory loop in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene. 2012;31(49):5073–5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller TW, Balko JM, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(33):4452–4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu J, Henske EP. Estrogen-induced activation of mammalian target of rapamycin is mediated via tuberin and the small GTPase Ras homologue enriched in brain. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9461–9466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cuesta R, Gritsenko MA, Petyuk VA, et al. Phosphoproteome analysis reveals estrogen-ER pathway as a modulator of mTOR activity via DEPTOR. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18(8):1607–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu SH, Al-Shaikh RA, Panossian V, Finerman GA, Lane JM. Estrogen affects the cellular metabolism of the anterior cruciate ligament. A potential explanation for female athletic injury. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(5):704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gu X, Yu JJ, Ilter D, Blenis N, Henske EP, Blenis J. Integration of mTOR and estrogen-ERK2 signaling in lymphangioleiomyomatosis pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(37):14960–14965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prizant H, Taya M, Lerman I, et al. Estrogen maintains myometrial tumors in a lymphangioleiomyomatosis model. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(4):265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamnik RL, Digilova A, Davis DC, Brodt ZN, Murphy CJ, Holz MK. S6 kinase 1 regulates estrogen receptor alpha in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(10):6361–6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamnik RL, Holz MK. mTOR/S6K1 and MAPK/RSK signaling pathways coordinately regulate estrogen receptor alpha serine 167 phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(1):124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alayev A, Salamon RS, Berger SM, et al. mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and activates ERα upon estrogen stimulation. Oncogene. 2016;35(27):3535–3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Le Romancer M, Poulard C, Cohen P, Sentis S, Renoir JM, Corbo L. Cracking the estrogen receptor’s posttranslational code in breast tumors. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(5):597–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madak-Erdogan Z, Ventrella R, Petry L, Katzenellenbogen BS. Novel roles for ERK5 and cofilin as critical mediators linking ERα-driven transcription, actin reorganization, and invasiveness in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(5):714–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Madak-Erdogan Z, Charn TH, Jiang Y, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Integrative genomics of gene and metabolic regulation by estrogen receptors α and β, and their coregulators. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ludwik KA, McDonald OG, Brenin DR, Lannigan DA. ERα-Mediated nuclear sequestration of RSK2 is required for ER+ breast cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2018;78(8):2014–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shrivastav A, Bruce M, Jaksic D, et al. The mechanistic target for rapamycin pathway is related to the phosphorylation score for estrogen receptor-α in human breast tumors in vivo. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(3):R49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu J, Astrinidis A, Howard S, Henske EP. Estradiol and tamoxifen stimulate LAM-associated angiomyolipoma cell growth and activate both genomic and nongenomic signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(4):L694–L700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136(4):731–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cuesta R, Berman AY, Alayev A, Holz MK. Estrogen receptor α promotes protein synthesis by fine-tuning the expression of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit f (eIF3f). J Biol Chem. 2019;294(7):2267–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ochnik AM, Peterson MS, Avdulov SV, Oh AS, Bitterman PB, Yee D. Amplified in breast cancer regulates transcription and translation in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2016;18(2):100–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang T, Birsoy K, Hughes NW, et al. Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science. 2015;350(6264):1096–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harris TE, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Rhoads RE, Lawrence JC Jr. mTOR-dependent stimulation of the association of eIF4G and eIF3 by insulin. Embo J. 2006;25(8):1659–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Csibi A, Communi D, Müller N, Bottari SP. Angiotensin II inhibits insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation and Akt activation through tyrosine nitration-dependent mechanisms. Plos One. 2010;5(4):e10070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maki PM. The timing of estrogen therapy after ovariectomy–implications for neurocognitive function. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4(9):494–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mosconi L, Berti V, Quinn C, et al. Perimenopause and emergence of an Alzheimer’s bioenergetic phenotype in brain and periphery. Plos One. 2017;12(10):e0185926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scheyer O, Rahman A, Hristov H, et al. Female sex and alzheimer’s risk: the menopause connection. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2018;5(4):225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yao J, Brinton RD. Estrogen regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics: implications for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;64:327–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Olokoba LB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of current trends. Oman Med J. 2012;27(4):269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prossnitz ER, Barton M. The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(12):715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barros RP, Machado UF, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: new players in diabetes mellitus. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12(9):425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Le May C, Chu K, Hu M, et al. Estrogens protect pancreatic β-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu S, Le May C, Wong WP, et al. Importance of extranuclear estrogen receptor-alpha and membrane G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in pancreatic islet survival. Diabetes. 2009;58(10):2292–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kumar R, Balhuizen A, Amisten S, Lundquist I, Salehi A. Insulinotropic and antidiabetic effects of 17β-estradiol and the GPR30 agonist G-1 on human pancreatic islets. Endocrinology. 2011;152(7):2568–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giordano S, Hage FG, Xing D, et al. Estrogen and cardiovascular disease: Is timing everything? Am J Med Sci. 2015;350(1):27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sickinghe AA, Korporaal SJA, den Ruijter HM, Kessler EL. Estrogen contributions to microvascular dysfunction evolving to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baker L, Meldrum KK, Wang M, et al. The role of estrogen in cardiovascular disease. J Surg Res. 2003;115(2):325–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dubey RK, Imthurn B, Zacharia LC, Jackson EK. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease what went wrong and where do we go from here? Hypertension. 2004;44:789–795. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50. Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E. The role of 17β-estradiol and estrogen receptors in regulation of Ca2+ channels and mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wyckoff MH, Chambliss KL, Mineo C, et al. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors are coupled to endothelial nitric-oxide synthase through Galpha(i). J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):27071–27076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(7):726–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lindner V, Kim SK, Karas RH, Kuiper GG, Gustafsson JA, Mendelsohn ME. Increased expression of estrogen receptor-beta mRNA in male blood vessels after vascular injury. Circ Res. 1998;83(2):224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schuster I, Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of oestrogen receptor β improves survival and cardiac function after myocardial infarction in female and male mice. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130(5):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Prizant H, Hammes SR. Minireview: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): the “other” steroid-sensitive cancer. Endocrinology. 2016;157(9):3374–3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Berger U, Khaghani A, Pomerance A, Yacoub MH, Coombes RC. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and steroid receptors. An immunocytochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93(5):609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kinoshita M, Yokoyama T, Higuchi E, et al. Hormone receptors in pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis. Kurume Med J. 1995;42(3):141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE. Decline in lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: relation to menopause and progesterone treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Prizant H, Sen A, Light A, et al. Uterine-specific loss of Tsc2 leads to myometrial tumors in both the uterus and lungs. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(9):1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Khaddour K, Shayuk M, Ludhwani D, Gowda S, Ward WL. Pregnancy unmasking symptoms of undiagnosed lymphangioleiomyomatosis: case report and review of literature. Respir Med Case Rep. 2019;26:63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]