Abstract

Objective:

To determine the associations between age at first postnatal corticosteroids (PNS) exposure and risk for severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI).

Study Design:

Cohort study of 951 infants born <27 weeks gestational age at NICHD Neonatal Research Network sites who received PNS between 8 days of life (DOL) and 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was used to produce adjusted odds ratios (aOR).

Results:

Compared to infants in the reference group (22–28 DOL-lowest rate), aOR for severe BPD was similar for children given PNS between DOL 8–49 but higher among infants treated at DOL 50–63 (aOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.03–3.06), and at DOL ≥64 (aOR 3.06, 95% CI 1.44–6.48). The aOR for NDI did not vary significantly by age of PNS exposure.

Conclusion:

For infants at high risk of BPD, initial PNS should be considered prior to 50 DOL for the lowest associated odds of severe BPD.

INTRODUCTION

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) remains one of the most common and serious neonatal morbidities, affecting more than 50% of surviving extremely premature infants.[1] Children with BPD often experience significant long-term pulmonary and neurodevelopmental sequelae, including cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment, and deafness.[2, 3, 4, 5] Postnatal administration of systemic corticosteroids (PNS) facilitates extubation and reduces the risks of BPD and mortality.[6, 7] However, this benefit may come at the cost of increased risk of cerebral palsy and other motor abnormalities,[6, 8, 9, 10, 11] particularly when dexamethasone is used in infants at low risk for BPD. Conversely, the balance of risks and benefits may favor use of dexamethasone among premature infants at high risk for BPD, in part because BPD is itself a risk factor for poor neurodevelopment.[1, 11, 12, 13]

Ideally, timing of PNS administration should maximize pulmonary benefit without increasing neurodevelopmental risk. However, the “optimal” timing is unknown. Due to safety concern with “early” exposure, recommendations have been made to limit PNS to those with evolving chronic lung disease and failure to extubate after 1–2 weeks of life.[6, 14] The average age of first exposure to PNS has drifted toward 4 weeks of life,[15, 16] although the safety and efficacy of this current practice is unclear. This postponement in PNS may delay extubation and increase cumulative days of exposure to mechanical ventilation, which has been associated with development of BPD and neurodevelopmental impairment.[17, 18, 19]

We conducted this study to characterize, in extremely preterm infants, the associations between the chronological age at first PNS exposure started after the first week of life and the risks of severe BPD and neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) as assessed at 2 years’ corrected age. Our goal was to identify a chronological age for initiation of PNS that is associated with the lowest risks for both BPD and NDI. We hypothesized that the relationships between age at first PNS exposure and BPD and NDI are non-linear, and that highest rates of adverse outcomes would be associated with both the earliest age at exposure (sicker children) and with the latest age at PNS exposure (longer invasive ventilation exposure).

METHODS

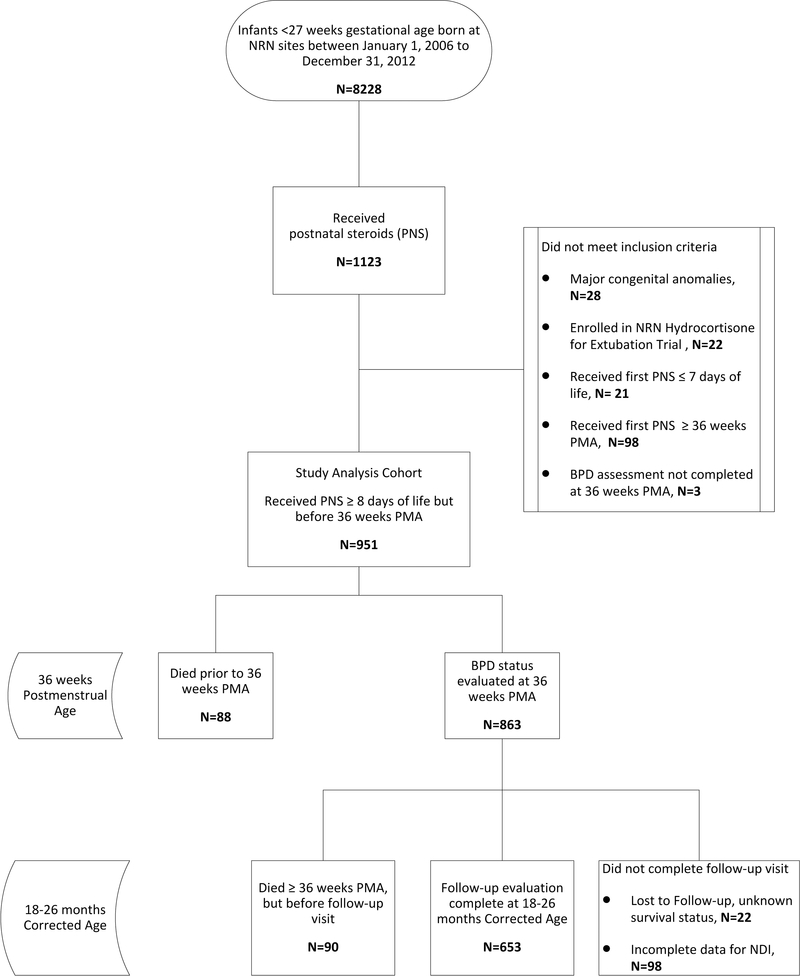

This was a retrospective cohort study of prospectively collected data of extremely preterm infants (<27 weeks’ gestational age) who first received PNS with the specified indication of the prevention or treatment of BPD between 8 days of life and 35 6/7 weeks’ postmenstrual age (PMA). This time period was selected to fall after the “early” period of corticosteroid administration to correspond to the common practice of starting steroids after the first week (non-prophylactic) of life to treat evolving BPD [6, 14], but before the official diagnosis of BPD could be made at 36 weeks’ PMA. Infants were compared between PNS exposed groups, rather than unexposed controls, to allow for comparisons based specifically on PNS timing for infants. Infants were born at participating Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN) centers between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2012. Infants with major congenital anomalies, infants who were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone for BPD, and infants for whom respiratory outcomes were unknown were excluded (Figure 1). Data for the NRN Generic Database (GDB) were collected by trained research personnel and include demographic characteristics, delivery information, medical morbidities, detailed respiratory data at pre-specified time points, and age at first treatment with systemic steroids for lung disease. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed with standardized developmental testing and neurologic examinations conducted at 18–26 months’ corrected age (CA). The institutional review board at each study center approved the data collection for the GDB and follow-up studies. Signed informed consent was obtained from parent or guardian for all children participating in follow-up.

Figure 1:

Participant flow diagram.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were severe BPD at 36 weeks’ PMA and neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) at follow-up, as well as the composite outcomes of severe BPD or death before 36 weeks PMA, and death or NDI at 18–26 months’ CA. The composite outcomes were analyzed alongside BPD and NDI in survivors because mortality is a competing outcome in critically-ill infants such as those included in this study. The pulmonary outcome of severe BPD was selected due to its stronger association with NDI and long-term pulmonary sequela[20, 21]. Severe BPD was defined as ≥30% oxygen and/or positive pressure ventilation at 36 weeks PMA.[22] The NICHD NRN definition of severe NDI was selected for our primary developmental outcome measure due to the expected high levels of delay seen in extremely preterm infants with severe respiratory morbidity[4, 5]. NDI was defined as any of the following: Cognitive Composite score <70 or Motor Composite score <70 (for those born after 1/1/2010, when the motor assessment was added to the NRN testing battery) on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-3),[23] moderate-to-severe cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Function Classification Scale level of ≥2),[24] visual impairment (<20/200 bilaterally), or permanent hearing loss (requiring bilateral amplification or cochlear implant). All children were evaluated using the Bayley-3 assessment. Secondary descriptive outcomes of interest were additional respiratory outcomes and detailed neurodevelopmental outcomes (Bayley subtests, neurosensory outcomes, and Brief Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA)).

Analyses

To characterize associations between timing of PNS and the study outcomes, we used a stepwise approach to the statistical analyses. To describe the study population and identify important variables for inclusion in our risk-adjustment models, we first dichotomized PNS exposure as “early” if the medication was started on or before 28 days of life and “late” if started after 28 days of life. Demographic and neonatal characteristics and outcomes were compared between early and late steroid initiation groups using Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Second, to test the hypothesis that the associations between age at first PNS exposure and the primary study outcomes were non-linear, we performed separate analyses with age at first steroid exposure defined as a continuous variable and as an ordered categorical variable. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) plots were created to examine the relationships between age at PNS initiation and each of the primary study outcomes.[25, 26] Knots were set a priori at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile distribution points. Tests of linearity were performed on the resulting spline covariates using Wald tests.

Hierarchical multivariable logistic regression was then used to assess the associations between chronological age at first steroid exposure, defined as a categorical variable, and the risks for severe BPD or NDI. The categories for chronological age were as follows: each week of postnatal life between week 2 and week 5, then (because of smaller sample sizes) each 2-week period between weeks 6–12. The approximate inflection point identified in the RCS plots was used as the reference category in these models.

Logistic regression models and RCS plots were both adjusted for center as a fixed effect, respiratory characteristics in the first week of life (days on invasive ventilation in the first week of life and highest percent inspired oxygen on day of life 7), and baseline characteristics independently associated with BPD and/or NDI (gestational age, birth weight, sex, treatment with antenatal steroids, small for gestational age (<10th centile birth weight)[27], private insurance status). Models of NDI were also adjusted for year of birth to account for changes in the components of the motor assessment over time. Results of the adjusted logistic regression models were summarized using forest plots. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Forest and RCS plots were created using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). P values <0.05 were considered significant and no adjustments were made for multiple testing.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 8228 infants were born before 27 0/7 weeks of gestation during the study period, of whom 951 infants (11.6%) at 25 NRN centers met all study eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Nineteen percent (178/951) of the cohort died. Of these deaths, 49% (88/178) occurred before 36 weeks PMA and 51% (90/178) occurred between 36 weeks PMA and 2-year follow-up. Complete developmental outcome data were available for 84% (653/773) of survivors. The patients with complete follow up data allowing determination of NDI status when compared to survivors without this data, had similar levels of severe BPD, age at steroid initiation, and demographic characteristics, while those without NDI data had higher birthweight (708±132 g vs 682 ± 133g, P <0.05) and lower exposure to antenatal steroids (82% (97/120) vs 91%(592/653), P =0.01). The name of the steroid drug was collected after 4/1/2011; of the infants for whom this information is known, 73% (206/281) received dexamethasone and 27% (75/281) received hydrocortisone. The median age at initiation of PNS was 31 days (IQR 21–45).

Baseline characteristics of children who received early (≤ 28 days) versus late (>28 days) steroids were similar except for marginally lower birth weight, higher rate of private insurance, and longer duration of exposure to invasive mechanical ventilation during the first week of life in the early group (Table 1). Neonatal morbidities were similar in the early and late steroid exposure groups except for the rate of PDA ligation, which was less common in the early steroid group (21% vs. 29%, P <.01).

Table 1.

Maternal and Infant Characteristics for First Steroid Exposure- Early vs. Late

| Steroid Exposure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Early (≤28 d) | Late (>28 d) | P | |

| n=951 | n=420 | n=531 | ||

| Steroid Initiation | ||||

| Median day of life (IQR) | 31 (21–45) | 21 (16–25) | 43 (35–54) | n/a |

| PMA (weeks), mean ± SD | 29.8±2.5 | 27.7±1.3 | 31.4±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Infant Characteristics | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks), mean ± SD | 24.9±1.0 | 24.9±1.0 | 24.9±1.0 | 0.36 |

| Birth weight (g), mean ± SD | 679±136 | 669±132 | 687±136 | 0.04 |

| Male, n (%) | 525 (55.2) | 217 (51.7) | 308 (58.0) | 0.06 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 84 (8.8) | 37 (8.8) | 47 (8.9) | >.99 |

| Multiple birth, n (%) | 222 (23.3) | 97 (23.1) | 125 (23.5) | 0.88 |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Maternal antenatal steroids, n (%) | 851 (90.6) | 385 (91.7) | 466 (87.9) | 0.07 |

| Chorioamnionitis, n (%)1 | 456 (57.5) | 200 (56.0) | 256 (58.7) | 0.47 |

| Private insurance, n (%)2 | 409 (43.4) | 199 (47.6) | 210 (40.0) | 0.02 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)3 | 0.58 | |||

| African American | 338 (36.2) | 153 (37.0) | 185 (35.6) | |

| White | 555 (59.4) | 246 (59.4) | 309 (59.4) | |

| Other | 41 (4.4) | 15 (3.6) | 26 (5.0) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.08 | |||

| < High school | 170 (17.9) | 62 (14.8) | 108 (20.3) | |

| High school graduate | 256 (26.9) | 120 (28.6) | 136 (25.6) | |

| College | 436 (45.8) | 203 (48.3) | 233 (43.9) | |

| Unknown | 89 (9.4) | 35 (8.3) | 54 (10.2) | |

| Early Respiratory Characteristics | ||||

| Intubated at birth, n (%) | 856 (90.0) | 384 (91.4) | 472 (88.9) | 0.23 |

| Received surfactant, n (%) | 921 (96.8) | 410 (97.6) | 511 (96.2) | 0.26 |

| Days on HFV during first week of life, mean ± SD | 2.7±2.9 | 2.8±2.8 | 2.6±2.9 | 0.36 |

| Days on CV during first week of life, mean ± SD | 3.4±2.8 | 3.7±2.7 | 3.2±2.8 | <0.01 |

| Days on HFV or CV during first week of life, mean ± SD | 6.2±1.8 | 6.5±1.3 | 5.9±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Invasive Ventilation for first 7 days of life, n (%) | 713 (75.0) | 345 (82.1) | 368 (69.3) | <0.001 |

| Highest FIO2 on day of life 7, mean ± SD | 0.46±0.21 | 0.49±0.23 | 0.43±0.20 | <0.001 |

| Neonatal Morbidities | ||||

| Late onset sepsis, n (%) | 392/951 (41.2) | 165 (39.3) | 227 (42.8) | 0.29 |

| Meningitis, n (%) | 27/951 (2.8) | 8 (1.9) | 19 (3.6) | 0.17 |

| Grade III/IV IVH, n (%) | 161/951 (16.9) | 72 (17.1) | 89 (16.7) | 0.93 |

| PVL, n (%) | 43/951 (4.5) | 19 (4.5) | 24 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| PDA, n (%) | 636/951 (66.9) | 277 (66.0) | 359 (67.6) | 0.63 |

| PDA ligation, n (%) | 241/951 (25.4) | 86 (20.5) | 155 (29.2) | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal perforation, n (%) | 60/951 (6.3) | 20 (4.8) | 40 (7.5) | 0.11 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis, n (%) | 92/951 (9.7) | 42 (10.0) | 50 (9.4) | 0.83 |

| Severe ROP, n (%)4 | 757/884 (85.6) | 320 (86.7) | 437 (84.8) | 0.50 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). P values are from chi-square exact tests for categorical variables, and t-tests for continuous variables, contrasting age groups of >28 days vs ≤28 days age for initiation of first steroids.

Data missing for 17% of infants.

Data missing for 1% of infants.

Data missing for 2% of infants.

Severe ROP= stage ≥ 3, data missing for 7% of infants.

IQR=Interquartile range, PMA=post-menstrual age, GA=gestational age, SD=standard deviation, HFV=High frequency ventilation, CV=conventional ventilation, FIO2= fraction of inspired oxygen, IVH=intraventricular hemorrhage, PVL=periventricular leukomalacia, PDA=patent ductus arteriosus, ROP= retinopathy of prematurity

Primary Outcomes

Among the infants who survived to 36 weeks’ PMA, 59.9% (517/863) had severe BPD. The composite outcome of death prior to 36 weeks PMA or severe BPD occurred in 63.6% (605/951). NDI was diagnosed in 25.1% (164/653) of survivors assessed at 18–26 months’ corrected age. The composite outcome of death or NDI at 18–26 months corrected age occurred in 41.2% (342/831).

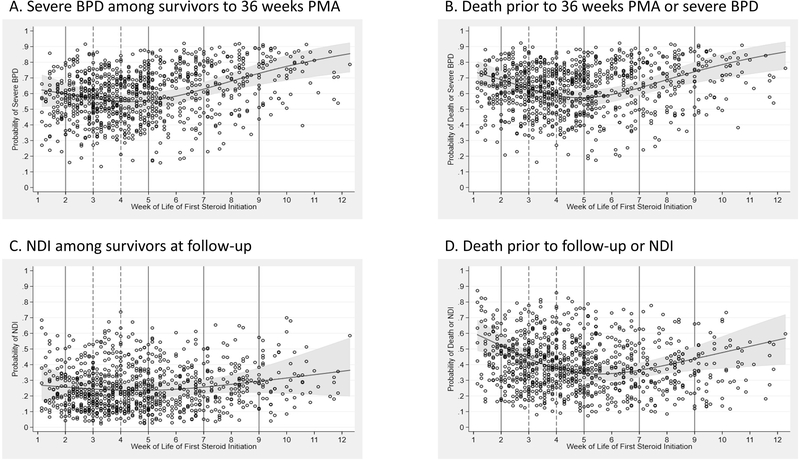

Figure 2 presents the RCS plots fit to the risk-adjusted probabilities for severe BPD, NDI, BPD or death before 36 weeks PMA, and NDI or death before 18–26 months, based on age at first exposure to PNS. Knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile points corresponded to 2, 4, and 8 weeks of life, respectively. Wald tests of the resulting spline covariates showed a significantly nonlinear relationship between age and the probability of each outcome (P <0.001, each). For all study outcomes, the RCS plots demonstrate a nadir in the probability curve at approximately 4–5 weeks of life.

Figure 2:

Restricted cubic spline models showing adjusted probabilities of ratios for primary outcomes (BPD, NDI) and primary outcome combined with death by categories based on age of first initiation of steroids. Dots are the adjusted probabilities of the outcome. Solid lines indicate the boundaries of the 7-age categories of steroid initiation and dashed line indicates reference group (4 weeks). Odds ratios are adjusted for private insurance status, antenatal steroids, gestation age, birthweight, small for gestational age, sex, days of high frequency and/or conventional ventilation (HFV/CV) in first week of life, fraction of inspired oxygen on day 7, and center as a fixed effect. Additionally, the NDI model was also adjusted for birth year to account for changes in the evaluation through time (changes in target age for follow-up window and addition of motor component).

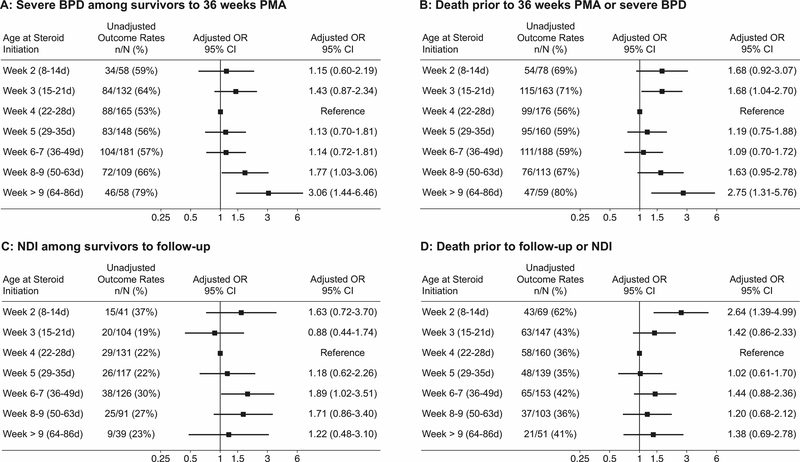

To further explore these nonlinear relationships, we performed multivariable logistic regression to quantify the odds of primary outcomes at multiple categories of ages at PNS initiation, as compared to the reference category of 4 weeks (days of life (DOL) 22–28 days). Figure 3 depicts these adjusted odds of severe BPD, NDI, and the composites with mortality. Compared to the reference group of infants first treated with PNS at 4 weeks, the aORs for developing severe BPD among survivors to 36 weeks PMA were similar among those beginning PNS during weeks 2 and 3 (DOL 8–21) and beginning during weeks 5–7 weeks (DOL 29–49) after birth. However, the aOR for severe BPD was significantly higher among infants treated with PNS starting in weeks 8–9 (DOL 50–63) (1.77, 95% CI 1.03– 3.06) and after 9 weeks (DOL ≥64) (3.06, 95% CI 1.44– 6.48). Logistic analyses of the composite outcome of BPD or death before 36 weeks PMA demonstrated a more significant U-shaped pattern with a higher aOR for death or BPD in those receiving steroids both early during week 3 of life (DOL 15–21) (1.68, 95% CI 1.04– 2.70) and late at week 10 or later (DOL ≥64) (2.75, 95% CI 1.31– 5.76), as compared to those exposed during the 4th week of life.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted rates and adjusted odds ratios for primary outcomes (BPD, NDI) and primary outcome combined with death by categories based on age of first initiation of steroids. Odds ratios are adjusted for private insurance status, antenatal steroids, gestation age, birthweight, SGA, sex, days of high frequency and/or conventional ventilation in first week of life (HFV/CV), fraction of inspired oxygen on day 7, and center as a fixed effect. Additionally, the NDI model was also adjusted for birth year to account for changes in the evaluation through time (changes in target age for follow-up window and addition of motor component).

The aOR of NDI at 18–26 months did not vary significantly when compared to the reference group, except for when PNS were initiated during week 6–7 of life (DOL 36–49) (1.89, 95% CI 1.02– 3.51; Figure 3). Similarly, the aOR point estimates for NDI or death before follow-up demonstrated a U-shaped pattern, but the differences were statistically significant only for infants in whom PNS were started during the second week of life (DOL 8–14) (2.64, 95% CI 1.39– 4.99).

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes are provided in Table 2. As expected, high rates of respiratory morbidity were seen in this cohort; 89% had moderate or severe BPD. Survivors received an average of 7 weeks of mechanical ventilation, with 63% discharged on oxygen. In bivariate analyses the early group (PNS started ≤28 days) were less likely to be discharged on oxygen (55% versus 68%, P <.001), were less likely to have moderate (<30% oxygen requirement at 36 weeks) or severe BPD (84% versus 92%, P <.001), and had fewer days of invasive ventilation and supplemental oxygen.

Table 2.

Outcomes with Age at First Exposure to Steroids (unadjusted)

| Steroid Exposure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Early (≤28 d) | Late (>28 d) | P, early vs. late | |

| n=951 | n=420 | n=531 | ||

| Pulmonary Outcomes at Discharge | ||||

| Severe BPD, n (%) | 517/863 (60.0) | 206 (57.9) | 311 (61.3) | 0.32 |

| Severe BPD or Death by 36 weeks’ PMA, n (%) | 605/951 (63.6) | 270 (64.3) | 335 (63.1) | 0.73 |

| Death by 36 weeks PMA, n (%) | 88/951 (9.2) | 64 (15.2) | 24 (4.5) | <.001 |

| 3-level BPD for infants who survived to 36 weeks’ PMA, n (%)1 | <.01 | |||

| Severe | 517/863 (60.0) | 206 (57.9) | 311 (61.3) | |

| Moderate | 246/863 (28.5) | 93 (26.1) | 153 (30.2) | |

| No/Mild | 100/863 (11.6) | 57 (16.0) | 43 (8.5) | |

| Days of ventilation, mean ±SD2, 3 | 51.4±23.6 | 47.9±23.4 | 53.8±23.5 | <.001 |

| Days of supplemental oxygen, mean ±SD2, 3 | 102.0±22.2 | 99.4±22.8 | 103.8±21.6 | <.01 |

| Discharged on oxygen, n (%)2, 4 | 476/759 (62.7) | 175 (55.4) | 301 (68.0) | <.001 |

| Tracheostomy, n (%)2 | 16/771 (2.0) | 4 (1.3) | 12 (2.6) | 0.21 |

| Length of stay (days), mean ±SD2,5 | 140.7±48.8 | 139.5±48.7 | 141.6±48.9 | 0.55 |

| PMA at discharge (weeks), mean ±SD2,5 | 45.0±6.9 | 44.8±6.9 | 45.2±6.9 | 0.52 |

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 18–26 Months Corrected Age | ||||

| NDI composite | 164/653 (25.1) | 64 (23.1) | 100 (26.6) | 0.26 |

| Death by follow-up | 179/929 (19.3) | 103 (24.8) | 76 (14.8) | <.001 |

| NDI composite or death | 342/831 (41.2) | 166 (43.8) | 176 (38.9) | 0.17 |

| Motor | ||||

| Bayley-3 motor composite <706,7 | 97/504 (19.2) | 45 (20.6) | 52 (18.2) | 0.82 |

| Bayley-3 motor composite <857 | 221/504 (43.8) | 94 (42.9) | 127 (44.6) | 0.30 |

| Gross motor function ≥ level 26 | 84/669 (12.6) | 32 (11.2) | 52 (13.5) | 0.17 |

| Moderate-to-severe CP6 | 53/669 (7.9) | 22 (7.8) | 31 (8.0) | 0.96 |

| Cognitive | ||||

| Bayley-3 cognitive composite <706 | 100/659 (15.2) | 40 (14.2) | 60 (15.9) | 0.65 |

| Bayley-3 cognitive composite <85 | 253/659 (38.4) | 113 (40.2) | 140 (37.0) | 0.19 |

| Language | ||||

| Bayley-3 language composite <70 | 157/643 (24.4) | 66 (24.0) | 91 (24.7) | 0.52 |

| Bayley-3 language composite <85 | 362/643 (56.3) | 168 (61.1) | 194 (52.7) | 0.24 |

| Sensory | ||||

| Blindness6 | 7/668 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) | 0.54 |

| Deafness6 | 21/670 (3.1) | 7 (2.5) | 14 (3.6) | 0.42 |

| Behavior | ||||

| BITSEA/problems >75%ile | 194/583 (33.3) | 93 (37.5) | 101 (30.2) | 0.08 |

| BITSEA/competencies <15%ile | 172/567 (30.3) | 81 (32.9) | 91 (28.4) | 0.27 |

Data are mean ±SD or n (%). P values are from chi-square exact tests for categorical variables, and t-tests for continuous variables, contrasting age groups of >28 days vs ≤28 days age for initiation of first steroids.

Mild BPD=Oxygen >21% for at least 28 days but room air at 36 weeks, Moderate=<30% oxygen requirement at 36 weeks, Severe= ≥30% oxygen and/ or positive pressure at 36 weeks.

Outcomes for survivors only.

Total Days of ventilation and supplemental oxygen by status missing for <0.1% of infants.

Of the 951 infants, 771 were discharged by 1 year of life. Of these, 2% were missing information.

Missing for 1% of infants.

Part of NDI composite.

Motor score only available for kids born after 2009.

BPD=bronchopulmonary dysplasia, PMA=post-menstrual age, NDI=Neurodevelopmental Impairment, Bayley 3=Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd Edition, BITSEA= Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment

For neurodevelopmental outcomes in the total surviving cohort, 15% had cognitive delay, 24% had language delay, and 19% had motor delay at 18–26 months corrected age. The rate of moderate or severe cerebral palsy was 8%. There were relatively low rates of blindness (1%) and deafness (3%).

DISCUSSION

In this large, cohort of extremely preterm infants exposed to PNS, we found a non-linear relationship between chronological age at first exposure to PNS and severe BPD. While the percentage of children with severe BPD was lowest at 22–28 days based on unadjusted rates and a nadir in the continuous graph was around 3–4 weeks, the adjusted odds ratios for both severe BPD and the composite outcome of BPD or death before 36 weeks’ PMA were similar when steroids were first started between 2–7 weeks of age (DOL 8–49). When evaluated by week of exposure, odds of severe BPD were significantly higher when PNS were first initiated during the eighth week of life or later (DOL ≥ 50), as compared to when steroids were started during the fourth week of life (DOL 21–28). While avoiding unnecessary steroid exposure for preterm infants is likely beneficial, there may be a limit around 50 days of life where the anti-inflammatory effects of PNS are less effective after more prolonged exposure to mechanical ventilation and hyperoxia. We did see higher rates of death and composites outcomes (BPD/NDI) including death with earlier PNS. Multiple previous RCT have shown PNS at >7 days improved survival until the first 28 days of life and with similar survival to discharge.[28]. The association between higher death with early steroids is likely not causal and is probable partially explained by survivor treatment selection bias, where the children who received steroids at a later day of life had by definition already survived to an older age. Also, based on clinical experience, patients selected to receive steroids in the first couple weeks of life likely had higher levels of medical acuity that may not have been fully accounted for by our model.

Only three published trials have randomized the timing of systemic PNS administration while looking at pulmonary outcomes. One large RCT trial (n=285) compared an early steroid arm (<72 hours) to a moderately early steroid arm (>15 days) and showed no difference in oxygen dependence or death at 36 weeks.[29] A second trial was a small pilot that compared PNS started at 7 vs 14 days and showed earlier extubation in the group that received steroids at 7 days but similar dependence on oxygen at 28 days and lung function at 3 months of age.[30] A third trial compared administration of PNS at 2 weeks of age to 4 weeks of age in 371 ventilated infants and showed no difference in ventilator dependence or oxygen at 36 weeks.[31] Consistent with our results, none of these three trials showed significant difference in respiratory outcomes for steroid exposure started at different intervals during the first month of life. Our study is the first to provide respiratory outcome data on patients initially provided steroids after 1 month of life and find the trend toward increased BPD if steroids are started after 7 weeks of life.

Only one study has looked at the risk of NDI by time of exposure PNS. An observational cohort study by Wilson-Costello and colleagues assessed neurodevelopmental outcomes by postmenstrual age at steroid exposure.[32] This study of children born between 2001 and 2004 showed a statistically significant increase in the risk for NDI with exposure to PNS at 33 weeks’ PMA or later.[32] Unlike the current study, the Wilson-Costello study captured all courses of steroids, including PNS given after 36 weeks’ PMA, and therefore provides more specific information on the impact of later use of steroids than the current study.

In addition to providing novel information about the associations between the timing of PNS exposure and prognostically-important outcomes, our study also provides valuable information for families about the range of respiratory and developmental outcomes for patients that are treated with PNS during their NICU course. Even after treatment with PNS, prolonged mechanical ventilation was common (mean duration 7 weeks), most infants had moderate or severe BPD, and the average age at discharge was 45 weeks PMA. Despite these risk factors for poor developmental outcomes, 75% of the population did not develop NDI and the 8% rate of moderate-to-severe CP was similar to the 7% rate previously published by the NRN for the birth cohort born 2008–2011.[33] Importantly, the standard NRN definition of NDI that was applied in this study only captures the most severely affected children. Rates of Motor, Language, and Cognitive Composite Bayley-3 scores greater than one standard deviation below the expected population mean in this cohort were between 38–56% and 12.6% of children had gross motor function classification level 2 or higher. These results suggest that children with moderate to severe BPD should be monitored closely after discharge, not only for signs of profound developmental delay but for more subtle delays that may have critical influence on long-term functioning.

Several limitations of this observational study are worthy of consideration. While we adjusted all models for important baseline characteristics, including early mechanical ventilation, there are likely remaining unmeasured confounders associated with the timing of steroid initiation. While the steroid type was not available on all participants, the majority of the cohort received dexamethasone and as such this study offers limited guidance on the optimal timing of hydrocortisone. The recent RCT of hydrocortisone vs placebo for the prevention of BPD started at 7–14 days of life, Stop-BPD[34], showed improved survival but no improvement in the rate of BPD with hydrocortisone. Based on this limited data, the inclusion of those patients exposed to hydrocortisone likely increased the rates of BPD and underestimated the effectiveness of PNS. Other limitations based on the available dataset include: incomplete data on respiratory severity at the time of steroid initiation, absence of data about cumulative PNS dosing, and subsequent courses of PNS. Lack of data on subsequent steroid courses limits our ability to assess the possible effect of steroid exposure during specific stages of brain maturation and subsequent developmental outcomes. Our use of the more severe NRN definition of NDI also limits our ability to potentially distinguish more subtle differences in development. We also had NDI status for 84% of the survivors. While baseline characteristics and demographics were largely similar for those with and without NDI status, we cannot exclude the possibility there were small differences in developmental outcomes. Lastly, despite the large sample size included in this study, samples per week of exposure were relatively small. This may have limited our power to detect important yet subtle changes in the odds of developing the study outcomes at specific time points. Nonetheless, this study reports outcomes of nearly a thousand extremely preterm infants who were exposed to PNS after the first week of life and provides novel models of the relationships between timing of PNS exposure and important short and long-term outcomes.

Postnatal corticosteroids continue to be commonly used to treat extremely premature infants with respiratory failure. A critical need remains for trials to determine the optimal use of systemic steroids for improving long-term pulmonary and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Hydrocortisone, while initially promising to provide positive anti-inflammatory lung effects without the negative effects on brain growth[35], has not demonstrated the same efficacy to reduce BPD when compared retrospectively to dexamethasone and will require further study.[7, 34] Currently an additional large placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone for infants with established lung disease is underway by the NRN and includes the critical elements of follow up of developmental and respiratory outcomes at both 2 and 5 years.[36] This and future studies are essential to determine optimal steroid type, dose, and timing for both the prevention of BPD, as well as the treatment of established lung disease.

In summary, our study suggests that when extremely preterm infants are treated with systemic steroids for management of BPD, treatment starting between 2 and 7 weeks (DOL 8–49) postnatal age is associated with no greater risk of neurodevelopmental delay and may potentially minimize the risk of severe BPD compared to later treatment of more established lung disease. For infants at high risk of BPD, initial postnatal steroid should be considered prior to 50 days of life for the lowest associated odds of severe BPD. Despite multiple risk factors for poor outcomes including PNS exposure, prolonged ventilation, and high rates of BPD, 75% of survivors in the current cohort did not have severe neurodevelopmental impairmant at 2-year follow-up.

Acknowledgements

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Generic Database and Follow-up Studies through cooperative agreements. While NICHD staff did have input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, Dr. Abhik Das (DCC Principal Investigator) and Mr. Douglas Kendrick (DCC Statistician) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study.

Financial Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through the Neonatal Research Network

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards:

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosures: Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data Sharing:

Data reported in this paper may be requested through a data use agreement. Further details are available at https://neonatal.rti.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=DataRequest.Home.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993-2012. Jama 2015, 314(10): 1039–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLean JE, DeHaan K, Fuhr D, Hariharan S, Kamstra B, Hendson L, et al. Altered breathing mechanics and ventilatory response during exercise in children born extremely preterm. Thorax 2016, 71(11): 1012–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh L, Kirkby J, Lum S, Odendaal D, Marlow N, Derrick G, et al. The EPICure study: maximal exercise and physical activity in school children born extremely preterm. Thorax 2010, 65(2): 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natarajan G, Pappas A, Shankaran S, Kendrick DE, Das A, Higgins RD, et al. Outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: impact of the physiologic definition. Early human development 2012, 88(7): 509–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Asztalos EV, Opie G, et al. Prediction of Late Death or Disability at Age 5 Years Using a Count of 3 Neonatal Morbidities in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. J Pediatr 2015, 167(5): 982–986.e982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Late (> 7 days) systemic postnatal corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 10: Cd001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baud O, Maury L, Lebail F, Ramful D, El Moussawi F, Nicaise C, et al. Effect of early low-dose hydrocortisone on survival without bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants (PREMILOC): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet 2016, 387(10030): 1827–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh TF, Lin YJ, Huang CC, Chen YJ, Lin CH, Lin HC, et al. Early dexamethasone therapy in preterm infants: a follow-up study. Pediatrics 1998, 101(5): E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh TF, Lin YJ, Lin HC, Huang CC, Hsieh WS, Lin CH, et al. Outcomes at school age after postnatal dexamethasone therapy for lung disease of prematurity. The New England journal of medicine 2004, 350(13): 1304–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Early (< 8 days) systemic postnatal corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 10: Cd001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle LW, Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Davis PG, Sinclair JC. Impact of Postnatal Systemic Corticosteroids on Mortality and Cerebral Palsy in Preterm Infants: Effect Modification by Risk for Chronic Lung Disease. Pediatrics 2005, 115(3): 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ancel P, Goffinet F, and the E-WG Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks’ gestation in france in 2011: Results of the epipage-2 cohort study. JAMA pediatr 2015, 169(3): 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle LW, Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Davis PG, Sinclair JC. An Update on the Impact of Postnatal Systemic Corticosteroids on Mortality and Cerebral Palsy in Preterm Infants: Effect Modification by Risk of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Pediatr 2014, 165(6): 1258–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Postnatal Corticosteroids to Prevent or Treat Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Pediatrics 2010, 126(4): 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, Stacey F, Marlow N, Draper ES. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies). The BMJ 2012, 345: e7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onland W, De Jaegere AP, Offringa M, van Kaam A. Systemic corticosteroid regimens for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 1: Cd010941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh MC, Morris BH, Wrage LA, Vohr BR, Poole WK, Tyson JE, et al. Extremely low birthweight neonates with protracted ventilation: mortality and 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes. The Journal of pediatrics 2005, 146(6): 798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen EA, DeMauro SB, Kornhauser M, Aghai ZH, Greenspan JS, Dysart KC. Effects of Multiple Ventilation Courses and Duration of Mechanical Ventilation on Respiratory Outcomes in Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants. JAMA pediatrics 2015, 169(11): 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi Y-B, Lee J, Park J, Jun YH. Impact of Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation in Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Results From a National Cohort Study. J Pediatr, 194: 34–39.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehrenkranz RA, Walsh MC, Vohr BR, Jobe AH, Wright LL, Fanaroff AA, et al. Validation of the National Institutes of Health consensus definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 2005, 116(6): 1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malavolti AM, Bassler D, Arlettaz-Mieth R, Faldella G, Latal B, Natalucci G. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia-impact of severity and timing of diagnosis on neurodevelopment of preterm infants: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2018, 2(1): e000165-e000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 163(7): 1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayley N Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development - Third Edition. Harcourt Assessment Inc: San Antonio, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental medicine and child neurology 1997, 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. RC_SPLINE: Stata module to generate restricted cubic splines. Statistical Software Components, S447301. 2004, https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s447301.html revised 14 Jan 2005 [cited] Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s447301.html

- 26.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis Spinger-Verlag New York, Inc: New York, NY, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstetrics and gynecology 1996, 87(2): 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL . Late (> 7 days) postnatal corticosteroids for chronic lung disease in preterm infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2014, 5: Cd001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halliday HL, Patterson CC, Halahakoon CW. A multicenter, randomized open study of early corticosteroid treatment (OSECT) in preterm infants with respiratory illness: comparison of early and late treatment and of dexamethasone and inhaled budesonide. Pediatrics 2001, 107(2): 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merz U, Peschgens T, Kusenbach G, Hornchen H. Early versus late dexamethasone treatment in preterm infants at risk for chronic lung disease: a randomized pilot study. European journal of pediatrics 1999, 158(4): 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papile L-A, Tyson JE, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Donovan EF, Bauer CR, et al. A Multicenter Trial of Two Dexamethasone Regimens in Ventilator-Dependent Premature Infants. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 338(16): 1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson-Costello D, Walsh MC, Langer JC, Guillet R, Laptook AR, Stoll BJ, et al. Impact of postnatal corticosteroid use on neurodevelopment at 18 to 22 months’ adjusted age: effects of dose, timing, and risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2009, 123(3): e430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vohr BR, Stephens BE, Higgins RD, Bann CM, Hintz SR, Das A, et al. Are outcomes of extremely preterm infants improving? Impact of Bayley assessment on outcomes. The Journal of pediatrics 2012, 161(2): 222–228 e223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onland W, Cools F, Kroon A, Rademaker K, Merkus MP, Dijk PH, et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone Therapy Initiated 7 to 14 Days After Birth on Mortality or Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Among Very Preterm Infants Receiving Mechanical Ventilation: A Randomized Clinical TrialEffect of Hydrocortisone on BPD and Mortality in Very Preterm Mechanically Ventilated InfantsEffect of Hydrocortisone on BPD and Mortality in Very Preterm Mechanically Ventilated Infants. Jama 2019, 321(4): 354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kersbergen KJ, de Vries LS, van Kooij BJ, Isgum I, Rademaker KJ, van Bel F, et al. Hydrocortisone treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia and brain volumes in preterm infants. The Journal of pediatrics 2013, 163(3): 666–671.e661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Hydrocortisone for BPD. May 13, 2011. ed. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine. [Google Scholar]