Abstract

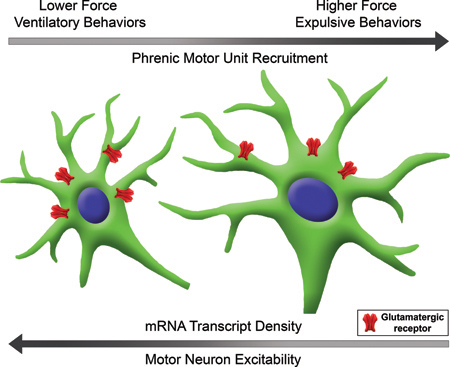

The diaphragm muscle comprises various types of motor units that are recruited in an orderly fashion governed by the intrinsic electrophysiological properties (membrane capacitance as a function of somal surface area) of phrenic motor neurons (PhMNs). Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter at PhMNs and acts primarily via fast acting AMPA and NMDA receptors. Differences in receptor expression may also contribute to motor unit recruitment order. We used single cell, multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization to determine glutamatergic receptor mRNA expression across PhMNs based on their somal surface area. In adult male and female rats (n=9) PhMNs were retrogradely labelled for analyses (n=453 neurons). Differences in the total number and density of mRNA transcripts were evident across PhMNs grouped into tertiles according to somal surface area. A ~25% higher density of AMPA (Gria2) and NMDA (Grin1) mRNA expression was evident in PhMNs in the lower tertile compared to the upper tertile. These smaller PhMNs likely comprise type S motor units that are recruited first to accomplish lower force, ventilatory behaviors. In contrast, larger PhMNs with lower volume densities of AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression presumably comprise type FInt and FF motor units that are recruited during higher force, expulsive behaviors. Furthermore, there was a significantly higher cytosolic NMDA mRNA expression in small PhMNs suggesting a more important role for NMDA-mediated glutamatergic neurotransmission at smaller PhMNs. These results are consistent with the observed order of motor unit recruitment and suggest a role for glutamatergic receptors in support of this orderly recruitment.

Keywords: Glutamate, Phrenic Motor Neurons, Motor unit recruitment, Respiration, Neurotransmitter, Neuromotor Control

Graphical Abstract

Orderly recruitment of motor units permits generation of graded levels of force necessary for a range of motor behaviors. There is considerable evidence that motor units innervating the main inspiratory muscle in mammals, the diaphragm muscle, are recruited according to the size principle (i.e., phrenic motor neurons with smaller surface area recruited first). The present study examined differences in the expression of excitatory glutamatergic (AMPA and NMDA) receptors across phrenic motor neurons of varying size and found size-dependent differences in receptor mRNA density across phrenic motor neurons which may contribute to the orderly recruitment of diaphragm motor units.

Introduction

A motor unit, comprising a motor neuron and the muscle fiber that it innervates, serves as the ultimate link between neural and motor control (Liddell & Sherrington 1925). Motor units vary greatly in their contractile and fatigue properties, but these properties are matched within the motor unit (Fournier & Sieck 1988; Burke et al. 1973; Sieck et al. 1989; Enad et al. 1989). Heterogeneity in motor unit properties allows the performance of a range of motor behaviors requiring varying amounts of force production. The diaphragm is a highly active muscle innervated by phrenic motor neurons (PhMNs) and comprise four types of motor units: slow-twitch, fatigue-resistant (type S) motor units, fast-twitch fatigue-resistant (type FR) motor units, fast-twitch, fatigue-intermediate (type FInt) motor units and fast-twitch, fatigable (type FF) motor units that are recruited in an orderly fashion (Fournier & Sieck 1988; Sieck et al. 1989; Burke 1981; Kernell 2006; Khurram et al. 2018). Heterogeneity across motor unit types is also reflected in differences in motor neuron somal size, axon size and axon conduction velocity (Clamann 1993). Current understanding posits that motor neuron recruitment within a motor unit pool is largely influenced by the distribution of motor neuron excitabilities for a given synaptic input, which has classically been defined by the size principle (Henneman et al. 1965b; Henneman et al. 1965a; Clamann & Henneman 1976). Accordingly, smaller motor neurons with less surface area and thus less membrane capacitance are recruited first compared to larger motor neurons with greater capacitance.

The main excitatory drive to PhMNs is glutamatergic and is mediated primarily by ionotropic AMPA and NMDA receptors (Ellenberger & Feldman 1988; Alilain & Goshgarian 2008; Tai & Goshgarian 1996; Mantilla et al. 2017; Rana et al. 2019). However, the expression of glutamatergic receptors across motor neurons comprising different motor unit types is unknown, yet differences in receptor expression across motor neurons may contribute to motor unit recruitment order. We hypothesize that AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression varies across PhMNs such that smaller PhMNs have a higher density of mRNA transcripts compared to larger PhMNs. Assessing the distribution of glutamatergic receptors across motor neurons of varying size in a well-defined, heterogeneous motor neuron pool such as the phrenic motor unit pool will provide important information regarding differences in the recruitment order of motor neurons beyond those associated with size-dependent, intrinsic electrophysiological properties determining motor neuron excitability.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Adult 3-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats (280–300g) of either sex were obtained from Envigo (Hsd:Sprague Dawley® SD, Indianapolis, IN) and used in this study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the American Physiological Society’s Animal Care Guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Mayo Clinic (Protocol No. A3105–17). Animals were housed individually in cages under a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) via intramuscular injection for all experimental procedures. This study was not pre-registered.

Phrenic motor neuron labeling and tissue collection

PhMNs were retrogradely labeled by injecting Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β (CTB-488) solution (Cat# C22841, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) bilaterally into the intrapleural space, as previously described (Rana et al. 2017; Gransee et al. 2015; Gransee et al. 2013; Mantilla et al. 2013; Mantilla et al. 2009; Alvarez-Argote et al. 2016). Two 10 μl injections of 0.2% CTB-488 each were administered on both sides of the thorax using a 20-gauge Hamilton syringe (Cat # 7731–10, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV). The pleural space was injected between the 7th and 8th ribs three days prior to the terminal experiment. Three days following CTB injections, the rats were euthanized with an anesthetic overdose followed by exsanguination. C2-C7 cervical spinal cord segments were excised and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen under RNase-free conditions. Longitudinal spinal cord sections (10 μm thick) were sectioned in a RNAse away treated cryostat (Leica CM 1860 UV, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) were placed on pre-chilled slides, and stored at −80°C until processing.

RNAscope in situ hybridization

In situ detection of AMPA and NMDA mRNA targets was performed using RNAscope® assay. Probe-Rn-Gria2-O2 (Cat# 508371, Accession No: AF164344.1 Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) was used to label Gria2 mRNA encoding the GluR2 subunit of AMPA receptors, which is widely expressed in the spinal cord (Tolle et al. 1993; Tolle et al. 1995; Furuyama et al. 1993). Probe-Rn-Grin1-C3 (Cat# 317021-C3, Accession No: NM_001270602 Advanced Cell Diagnostics) was used to label Grin1 mRNA encoding the obligatory NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors. The Gria2 and Grin1 subunits have previously been verified as being highly expressed in rat PhMNs (Gransee et al. 2017; Mantilla et al. 2012).

The manual multiplex fluorescent assay was performed using the Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit (Cat# 320850, Advanced Cell Diagnostics) and manufacturer recommended protocol for fresh frozen samples, with some modifications. Briefly, tissue fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin was followed by sequential dehydration with 50%, 70% and 100% ethanol that was prepared using DNAse free water. Sections were then pre-treated for 20 min with protease IV reagent followed by a 2-h incubation with the target probes in the HybEZ oven at 40°C. Probe amplification was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions using the Amp-4 AltB combination, thus labeling Gria2 and Grin1 with Atto 550 and Atto647, respectively. Tissue was counterstained with DAPI and cover-slipped with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Cat# P36934, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Slides were stored localization in the dentate gyrus region and cerebellum, which served as positive controls with abundant Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA expression observed in accordance with previous reports (Monyer et al. 1991; Watanabe et al. 1992). In conjunction with RNAse treatment, Gria2 and Grin1 signal was lost, confirming RNA selectivity of target probes.

Confocal imaging and analysis

Spinal cord sections were imaged using a confocal microscope (Nikon A1R multi-color/multichannel high-speed confocal system, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with A1 detection filters 450/50, 535/50,600/50 + 685/70 and interlock with four diode lasers (405nm, 488nm, 561nm, and 640nm). All images (12-bit, 1024 × 1024 pixel array) were obtained using a 40x Plan Fluor objective (NA 1.30) with 0.5 μm step size. Imaging parameters were selected by setting background as less than 10% of the dynamic range and preventing saturation. Retrogradely-labelled PhMNs were visualized and those with a distinct mid nuclear section with a visible nucleolus were selected for analyses of mRNA transcript. Maximum intensity projection images were obtained from the confocal z-stack for each identified PhMN.

Quantitative analysis of mRNA transcripts in individually identified PhMN cell bodies was performed using FIJI version 2.0.0 (RRID:SCR_002285, NIH, Bethesda, MD). Within a selected PhMN, mRNA transcripts were clearly visible as puncta of varying size and intensity. For each individual slide, the integrated fluorescence intensities and area of 20 discretely identifiable and clearly unclustered puncta was measured. After background subtraction, the average integrated intensity per puncta was obtained and equated to one mRNA transcript, with the experimenter blinded to PhMN group. To quantify the number of mRNA puncta transcripts per cell, a region of interest around the PhMN soma was drawn using the outline from the CTB image. The region of interest was then superimposed on the images for the other fluorescence channels and the integrated intensity for either AMPA or NMDA was measured separately for each mRNA transcript. The cross-sectional area of the PhMN cell body was then measured and used to determine the total background fluorescence, which was subtracted from the total fluorescence. The total number of mRNA transcripts was thus obtained for each PhMN.

Additional morphometric analyses were performed for each PhMN, as previously described (Prakash et al. 1993; Prakash et al. 1994; Prakash et al. 2000; Issa et al. 2010; Fogarty et al. 2018; Mantilla et al. 2018; Rana et al. 2019). Somal surface area and volume were estimated for a prolate spheroid by measuring the major and minor axes in the mid-nuclear section (Prakash et al. 2000). Estimated mRNA transcript density was obtained by dividing the total number of mRNA transcripts by the estimated PhMN somal volume. PhMNs were also grouped into tertiles according to size. Experimenter was blinded to animal and sex for all analyses.

Images were converted to 8-bit in NIS Elements (RRID:SCR_014329, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) for presentation only. No thresholding or post-image processing was applied for any images. For the purposes of presentation in Fig 1, each fluorescence channel was pseudocolored by specifying the following look-up tables (color gamut): blue for nuclear staining (405nm fluorescence), magenta for CTB (488nm fluorescence), red for Gria2 mRNA (594nm fluorescence) and green for Grin1 mRNA (647nm fluorescence).

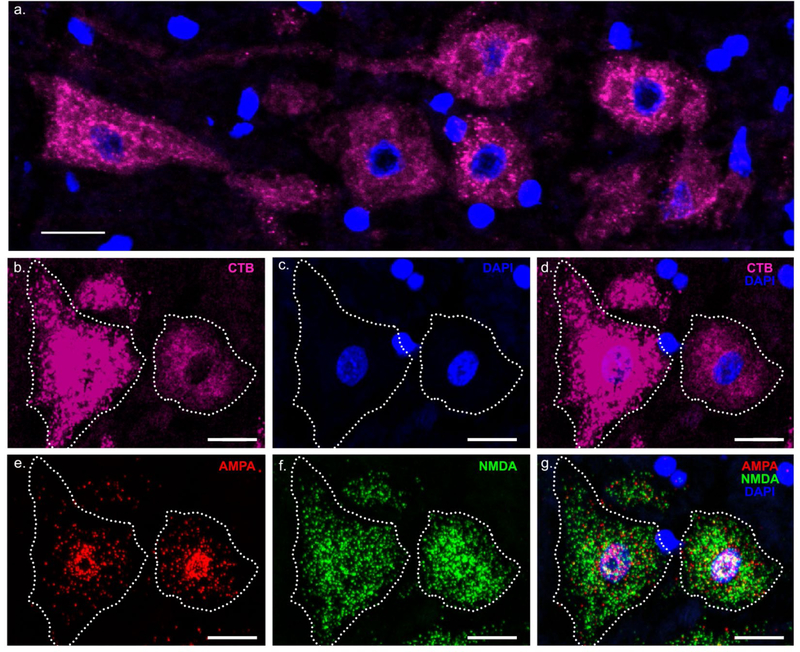

Figure 1. Multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNAscope) for AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression in phrenic motor neurons.

(a) Representative maximum intensity projection image shows a cluster of PhMNs that were identified by retrograde labelling using intrapleural Alexa 488-conjugated cholera toxin B (CTB-488). Image represented is pseudo-colored to magenta for clarity. (b) Soma of two labeled PhMNs with a distinct mid-nuclear section and visible nucleolus as shown by DAPI stain in (c.) was outlined (white dotted line). (d) Merged image illustrating CTB and DAPI. (e) and (f) illustrate single cell multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization for AMPA (Gria2 - Red) and NMDA (Grin1 - Green) mRNA transcripts. Quantitative fluorescence measurements were conducted in Fiji to determine the number of mRNA transcripts per motor neuron. (g) AMPA and NMDA mRNA channels are merged with DAPI stain. Note the high nuclear distribution of Gria2 mRNA. Scale bar: 20μm

Statistical analysis

All statistical evaluations were performed using JMP statistical software (RRID:SCR_014242, version 14.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The study statistical design was powered to consider the within subject variance in order to detect a 15% difference at p<0.05 based on preliminary studies documenting variance in PhMN NMDA mRNA transcript density showing a CV ~30% within an animal. Accordingly, we stereologically sampled 50 PhMNs per animal, which provided more than sufficient power to reject our null hypothesis that there were no differences in glutamatergic receptor mRNA across PhMNs. For measurements repeated for the same animal (e.g., mRNA transcript density and total number of mRNA transcripts per PhMN) also included PhMN somal surface area and sex as model variables. Normality of the distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test within each animal. Outliers were identified for each animal using an outlier box plot. No data was excluded from the analysis. An additional model was generated after grouping PhMNs into tertiles according size for each animal. A total of 5 male and 4 female rats were used in these experiments. All experimental data is presented as mean ± standard error (SE), unless otherwise specified. Using the mixed linear model, statistical significance was established at the 0.05 level and adjusted for any violation of the assumption of sphericity in repeated measures using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. When appropriate, post hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD).

Results

Phrenic motor neuron labeling and morphometry

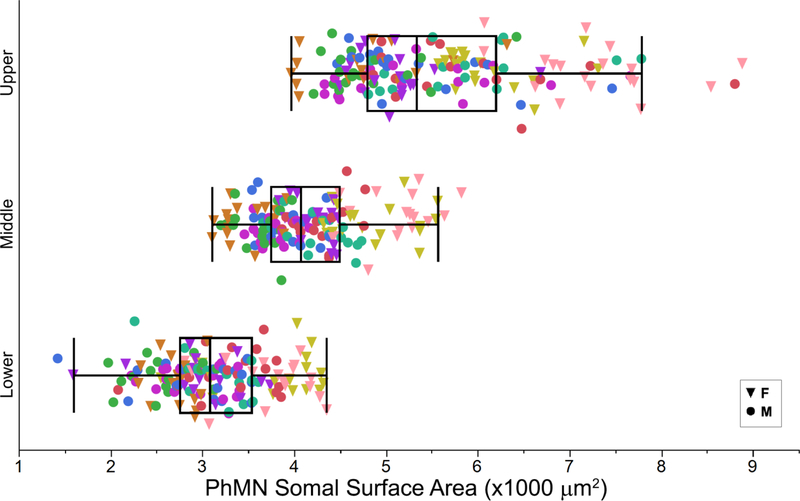

Intrapleural CTB-488 injections resulted in reliable labelling of the PhMN pool. PhMNs showed the expected clustering in the C3-C5 segments of the spinal cord, and were easily identified (Fig. 1). The fresh frozen tissue processing is necessary to preserve mRNA transcript levels, and protocol modifications allowed sufficiently clear visualization of PhMN soma such that the margins could be easily delineated in all cases, permitting reliable measurements of motor neuron dimensions. Only PhMNs containing a mid-nuclear section (with a visible nucleolus) were used to measure mRNA transcript density. The size of PhMNs (n = 462 PhMNs from 9 animals) was estimated using the long and short axis diameters of the mid-nuclear motor neuron profile assuming a prolate spheroid (Fig. 2). The mean PhMN long and short axis diameters were 48.3 ± 0.4 μm and 30.5 ± 0.3 μm, respectively. The mean somal volume and surface area were 25,968 ± 558 μm3 and 4,307 ± 59 μm2. There were statistically significant differences in PhMN surface area across animals (one-way ANOVA; F(8,461)=11.9; p<0.001), with mean surface area in each animal ranging from 3,687 to 5,358 μm2. Accordingly, PhMNs were also grouped into tertiles within each animal, and the mean surface area was 3,134 ± 48 μm2, 4,181 ± 49 μm2, and 5,597 ± 84 μm2 for the lower, middle and upper tertile, respectively.

Figure 2. Grouping of phrenic motor neurons according to somal surface area.

The somal surface areas of retrogradely labelled PhMNs were separated into tertiles for each animal (labeled by the different colors; n=9 rats). AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression was subsequently quantified in PhMNs grouped in the lower (n=154), middle (n=152) and upper (n=156) tertiles. Box plots of PhMN somal surface area represent variability in motor neuron size across motor neurons and animals.

AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression in phrenic motor neurons

Measurements of mRNA transcript density were limited to labeled PhMNs. Extensive expression of Gria2 (encoding GluR2 subunit of AMPA receptors) and Grin1 (encoding NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors) mRNA was observed in cell bodies in grey matter of the spinal cord. For both Gria2 and Grin1, mRNA transcripts were abundant in cell bodies with relatively low expression in spinal cord regions that would pertain to dendrites and axons (Fig. 1). Puncta were clearly visible in larger cells in the gray matter of the spinal cord suggesting that there is limited mRNA expression in other cells including glia. Indeed, the single cell multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization technique revealed abundant Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA expression in retrogradely-labelled PhMNs.

Both Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA probes showed discrete individual mRNA transcripts, as well as transcript clustering that was thus considered in conducting quantitative analysis of the number of mRNA puncta, as described in the Methods. We used an intensity-based analysis to quantify total mRNA expression across PhMNs of varying sizes. There was no effect of sex on any of the variables measured, and thus sex was removed from the mixed linear model.

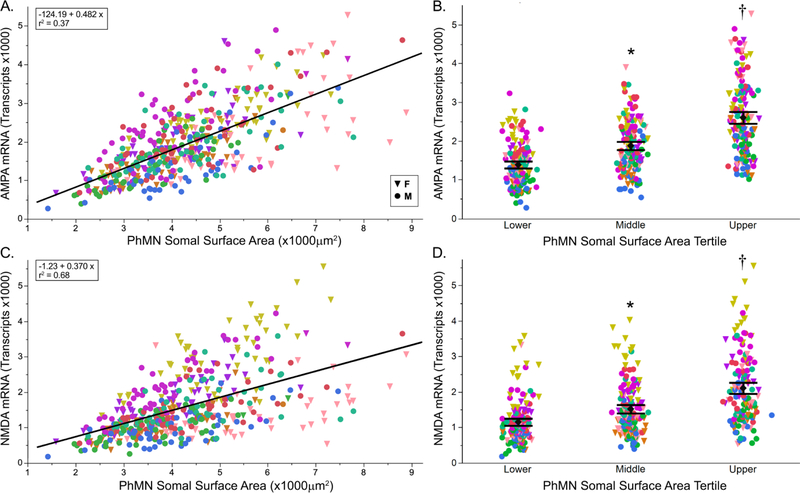

Number of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts in phrenic motor neuron soma

Total number of Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcripts were positively correlated with PhMN size (Fig. 3). On average, the number of Gria2 mRNA transcripts per PhMN was 1954 ± 42. There were statistically significant differences in total number of Gria2 mRNA transcripts across animals (one-way ANOVA; F(8,461)=15.5; p<0.001), with mean number of mRNA transcripts ranging from 1362 to 2544. Within animals, there were fairly large variances in the distribution of Gria2 mRNA transcripts per PhMN (CV ~40%). Accordingly, by considering the animal effect a random factor in the mixed linear model, our experimental design minimizes the impact of animal differences and emphasizes within animal differences across motor neuron populations of varying somal surface area. In the mixed linear model using animal as a random effect, PhMN somal surface area had a significant effect on the number of Gria2 mRNA transcripts (F(1,459)=430.7; p < 0.001) with number of Gria2 mRNA transcripts showing a strong positive correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.60). On average, the number of Grin 1 transcripts per PhMN was 1597 ± 42. There were statistically significant differences in total number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts across animals (one-way ANOVA; F(8,461)=46.2; p<0.001), with mean number of mRNA transcripts ranging from 990 to 2930. Within animals, there were fairly large variances in the distribution of Grin1 mRNA transcripts per PhMN (CV ~40%). In the mixed linear model using animal as a random effect, PhMN somal surface area had a significant effect on the number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts (F(1,454.6)=325.7; p < 0.001) with number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts showing a very strong positive correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.68).

Figure 3. Total number of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts per PhMN according to motor neuron somal surface area.

Total number of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts per PhMN increase with increasing motor neuron somal surface area (n = 462 PhMNs from 9 rats). A. Total number of AMPA (Gria2) mRNA transcripts showed a strong positive correlation with motor neuron somal surface area (r2 = 0.37). C. Total number of NMDA (Grin1) mRNA transcripts showed a very strong positive correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.68). Different animals are shown by the various colors. B, D. Mean (± 95% CI) total number of AMPA (B) and NMDA (D) mRNA transcripts per PhMN grouped by somal surface area tertile. (*, significantly different from the lower tertile; †, different from middle tertile; post hoc Tukey-Kramer HSD, p<0.05).

The numbers of Gria2 and Grin1 transcripts were also compared across PhMNs grouped into tertiles according into surface area for each animal (Fig. 3B,D). There was an effect of PhMN surface area tertile on total number of Gria2 transcripts in PhMNs (F(2,451)=148.8; p<0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically-significant pairwise differences in the number of Gria2 mRNA transcripts, with Gria2 mRNA transcripts increasing from the lower tertile to the middle and to the upper tertile. Total number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts also varied with PhMN tertiles (F(2,451)=125.5; p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically-significant pairwise differences in the number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts, with Grin1 mRNA transcripts increasing from the lower tertile to the middle and to the upper tertile.

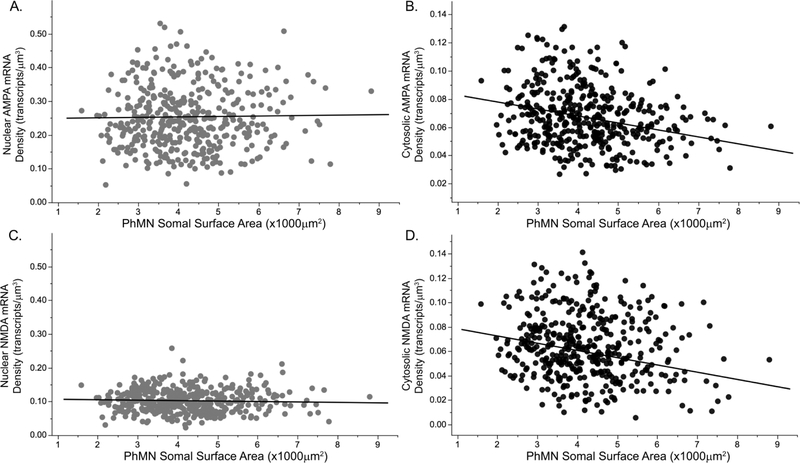

Density of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts in phrenic motor neuron soma

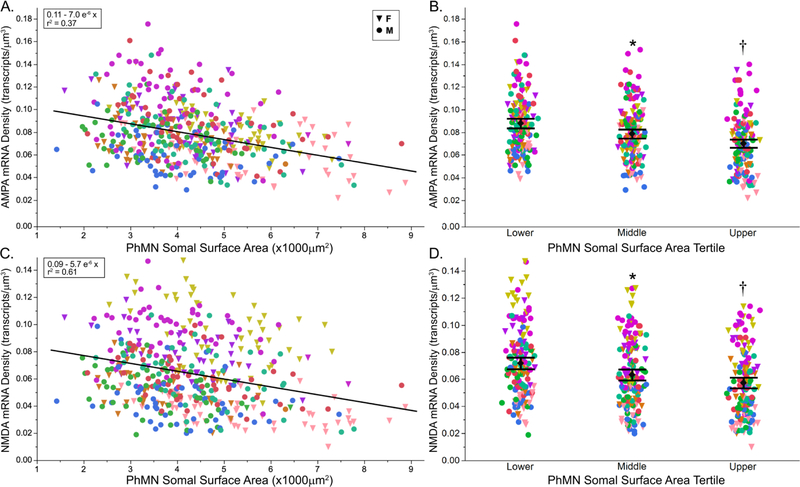

To assess Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcript density in each PhMN, the number of mRNA transcripts was normalized to optical slice volume for the mid-nuclear motor neuron section (Fig. 4). The average density of Gria2 mRNA transcripts per PhMN was 0.079 ± 0.021 transcripts/μm3. There were statistically significant differences in density of Gria2 mRNA transcripts per PhMN across animals (one-way ANOVA; F(8,461)=21.1; p<0.001). The correlation between Gria2 mRNA transcript density and PhMN somal surface area was estimated using a mixed linear model, with animal as a random effect. There was a significant effect of PhMN somal surface area on Gria2 mRNA density (F(1,457.9)=70.6; p<0.001), with Gria2 mRNA density showing a strong negative correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.37).

Figure 4. AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density per PhMN according to motor neuron somal surface area.

AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density per PhMN (μm−3) decrease with increasing motor neuron somal surface area (n = 462 PhMNs from 9 rats). A. AMPA (Gria2) mRNA transcript density showed a strong negative correlation with motor neuron somal surface area (r2 = 0.37). C. NMDA (Grin1) mRNA transcript density showed a strong positive correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.61). B, D. Mean (± 95% CI) of AMPA (B) and NMDA (D) mRNA transcript density per PhMN grouped by somal surface area tertile. (*, significantly different from the lower tertile; †, different from middle tertile; post hoc Tukey-Kramer HSD, p<0.05).

The average density of Grin1 mRNA transcripts per PhMN was 0.065 ± 0.017 transcripts/μm3. There were statistically significant differences in total number of Grin1 mRNA transcripts across animals (one-way ANOVA; F(8,461)=67.1; p<0.001). Grin1 mRNA transcript density was then compared across PhMN somal surface area using a mixed linear model, with animal as a random effect. There was a significant effect of PhMN somal surface area on Grin1 mRNA density (F(1,454.2)=73.6; p < 0.001) with Grin1 mRNA density showing a strong negative correlation with PhMN somal surface area (r2 = 0.61).

Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcript density was also compared across PhMN tertiles (Fig. 4B,D). There was an effect of PhMN surface area tertile on Gria2 mRNA transcript density in PhMNs (F(2,451)=26.8; p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically-significant pairwise differences in the density of Gria2 mRNA transcripts, with Gria2 mRNA transcript density decreasing from the lower tertile to the middle and to the upper tertile. Grin1 mRNA transcript density also varied with PhMN tertile (F(2,451)=27.9; p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically-significant pairwise differences in the density of Grin1 mRNA transcripts, with Grin1 mRNA transcript density decreasing from the lower tertile to the middle and to the upper tertile.

Density of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts in cytosolic and nuclear compartments

Gene expression requires a multi-level regulatory process that originates with mRNA transcription in the nucleus and is completed by translation in the cytosol. The relative distribution of mRNA across these compartments reflects the progress across steps in the gene expression process, such that cytosolic mRNA may more closely reflect protein translation (de Sousa Abreu et al. 2009; Akan et al. 2012). Accordingly, we compared total Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA expression across cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments within PhMNs (Fig. 5). Nuclear fractions were determined using the DAPI signal and cytoplasmic fraction was obtained by subtracting nuclear mRNA fraction from the total mRNA in each individual PhMN. As expected, nuclear volume showed a moderate positive correlation with estimated PhMN somal volume (F(1,414.2)=104.8; p<0.001).

Figure 5. Nuclear and cytosolic localization of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts in PhMNs.

AMPA (Gria2) and NMDA (Grin1) mRNA density differs across nuclear (light grey) and cytoplasmic (black) compartments within PhMNs (n = 417 PhMNs from 9 rats). AMPA mRNA density varied significantly across somal compartment, with higher Gria2 mRNA density in nuclear compartment (A) compared to cytosolic (B) compartment (note differences in y-axis range). There was no effect on AMPA mRNA density of PhMN surface area or an interaction between somal compartment and somal surface area. In contrast, NMDA mRNA transcript density was significantly different across neuron compartments, PhMN surface area and an interaction between compartment and surface area. NMDA mRNA density was considerably higher in the nuclear compartment (C) compared to cytosolic compartment (D). The correlation between nuclear NMDA mRNA density and PhMN surface area was not statistically significant but cytosolic NMDA mRNA density showed a strong negative correlation with PhMN surface area (r2 = 0.59).

In the mixed linear model using animal as a random effect, Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcript density was significantly different across neuron compartments. For Gria2 mRNA density, there was an effect of somal compartment (F(1,822.1)=2029.3; p<0.001), but no effect of PhMN surface area (F(1,829.9)=0.9; p=0.338) or an interaction between somal compartment and somal surface area (F(1,822.1)=3.1; p=0.074). There was a considerably higher Gria2 mRNA density in nuclear compartment compared to cytosolic compartment (0.25 mRNA transcripts/μm3 vs 0.07 mRNA transcripts/μm3, respectively). Differences in nuclear or cytosolic Gria2 mRNA density across PhMN surface area were no longer statistically significant. For Grin1 mRNA transcript density was significantly different across neuron compartments, with a significant effect of somal compartment (F(1,822)=392.4; p<0.001), PhMN surface area (F(1,828.3)=17.5; p<0.001) and an interaction between compartment and surface area (F(1,822)=5.8; p=0.016). The Grin1 mRNA density was considerably higher in the nuclear compartment compared to cytosolic compartment (0.10 mRNA transcripts/μm3 vs 0.06 mRNA transcripts/μm3 respectively). The correlation between nuclear Grin1 mRNA density and PhMN surface area was not statistically significant (F(1,415)=0.7; p=0.41). In contrast, cytosolic Grin1 mRNA density showed a strong negative correlation with PhMN surface area (F(1,408.5)=60.1; p < 0.001; r2=0.59).

Similar results were obtained when comparing Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcript density across neuron compartments when PhMNs were grouped into tertiles according to somal surface area. For Gria2 and Grin1 mRNA transcript density in PhMNs, there was a considerably higher mRNA density in the nuclear compartment compared to cytosolic compartment. Significant differences in mRNA transcript density were now mainly evident for cytosolic Grin1 mRNA density, with higher mRNA transcript density in the lower tertile compared to the upper tertile of PhMN somal surface area.

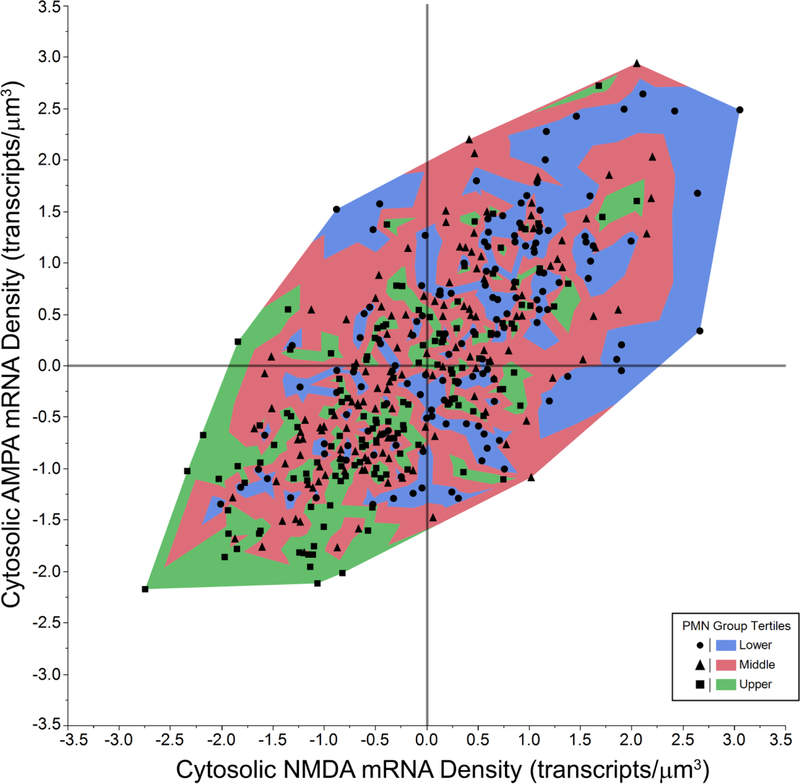

As an additional analysis, z-scores for cytosolic AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density were determined per PhMN for each animal and target probe (Fig 6). PhMNs showed a strong positive correlation between the cytosolic expression of AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcripts (F(1,416)=435.5; p < 0.001; r2 = 0.51). PhMNs with smaller surface area show the highest levels of both AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density in their cytosol, whereas those with larger surface show the lowest levels of cytosolic mRNA transcript density.

Figure 6. Z-score for cytosolic AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density in PhMNs.

Contour plot of Z-scores for cytosolic AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density per PhMN (n = 417 PhMNs from 9 rats). Z-scores were determined for the each target probe within each animal. The color scale increases in PhMN surface area from blue to red. PhMNs with smaller surface area are found predominantly in the positive z-score quadrants and those with larger surface area in the negative z-score quadrants.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression varies across PhMNs such that smaller PhMNs have a higher density of mRNA transcripts compared to larger PhMNs. The main excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system is glutamate, with AMPA and NMDA receptors acting as the major ionotropic glutamate receptors. Since mRNA levels are generally correlated with protein levels (de Sousa Abreu et al. 2009; Maier et al. 2009), these results suggest that smaller PhMNs have a higher density of AMPA and NMDA receptors compared to larger PhMNs, and thus differences in glutamatergic receptor density across motor neurons of varying size (motor unit type) may contribute to the orderly recruitment of motor units. The size principle (Henneman et al. 1965b; Henneman et al. 1965a; Clamann & Henneman 1976) posits that the somal surface area of motor neurons dictates the orderly recruitment of motor neurons, such that motor neurons with smaller surface area have lower membrane capacitance and therefore, elicit a higher change in membrane voltage for a given amount of synaptic current. A higher receptor expression in smaller PhMNs would allow a greater change in post synaptic membrane potential for a given amount of synaptic input, thus contributing to the excitability of the motor neuron. Taken together, our results support the orderly recruitment of PhMNs based on their size.

Source of glutamatergic innervation of phrenic motor neurons

The origins and organization of excitatory synaptic inputs to PhMNs have been mapped using a number of approaches including, but not limited to, neuroanatomical studies with tracers, lesions, antidromic stimulation as well as correlational studies using intra- and extracellular recordings from PhMNs and afferent input sources (Lee & Fuller 2011; Ghali 2017). Monosynaptic excitatory inputs from the rVRG constitute the most prominent bulbospinal inputs to PhMNs (Ellenberger & Feldman 1988; Ellenberger et al. 1990; Lipski et al. 1994; Dobbins & Feldman 1994; Tian & Duffin 1996a; Tian & Duffin 1996b). Progress in anatomical tracing techniques over the past few decades has unraveled the presence of interneuron populations in the upper cervical spinal cord that also innervate PhMNs (Lipski et al. 1993; Lipski et al. 1994; Lane et al. 2008b). Supraspinal inputs with medullary origins in respiratory centers terminate in upper cervical segments (Tian & Duffin 1996a). Cervical interneurons from these segments send projections to PhMNs (Dobbins & Feldman 1994; Lane et al. 2008b; Lane et al. 2008a), constituting a putative pre-phrenic interneuron population(Sandhu et al. 2009). The neurotransmitter characteristics of this interneuron population remain to be determined, but likely comprise glutamatergic inputs to motor neurons. It is noteworthy that these projections appear to be limited in number. There also exists a population of propriospinal excitatory inputs from intercostal motor neurons to PhMNs that comprise the intercostal to phrenic reflex (Decima et al. 1969; Remmers 1973; Lane et al. 2008b). These inputs have been shown to preserve the size dependent activation or inactivation of PhMNs in response to intercostal afferent stimulation (Decima et al. 1969).

In a recent study, we evaluated size dependent distribution of excitatory glutamatergic terminals at PhMNs varying by size (Rana et al. 2019). We observed ~10% higher density of pre-synaptic glutamatergic terminals on PhMNs in the lower tertile as compared to the upper tertile when grouped based on somal surface area. In the present study, we detected a ~25% higher expression of AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression in PhMNs of the lower tertile compared to those in the upper tertile. Taken together, these support matching of pre and post synaptic mechanisms at PhMNs that contribute to the orderly recruitment of motor units.

Glutamatergic neurotransmission at phrenic motor neurons

Glutamate is the main fast acting excitatory neurotransmitter at PhMNs (McCrimmon et al. 1989; Saji & Miura 1990; Greer et al. 1992; Rana et al. 2019). Multiple reports document the presence of two key ionotropic receptors mediating glutamatergic neurotransmission at PhMNs, AMPA and NMDA receptors (Liu et al. 1990; Chitravanshi & Sapru 1996; Alilain & Goshgarian 2007; Mantilla et al. 2012; Gransee et al. 2017; Mantilla et al. 2017). In the present study, the total number of glutamatergic mRNA transcripts per PhMN varied considerably across motor neurons of varying size. However, differences in transcript number were considered in light of the surface area of PhMNs given that membrane receptors such as glutamate receptors exert their effect on motor neuron excitability based on their density on the membrane. Accordingly, most of our discussion will reflect differences in transcript density.

AMPA receptors modulate neuronal excitability by rapid activation in response to glutamate release at a synaptic site and are permeable to Na+ and K+ ion channels (Traynelis et al. 2010), thus determining neuron firing rates. AMPA receptors exist as heterotetramers which comprise various combinations of its four subunits GluR1–4 (Greger et al. 2017). Although all four subunits are present in rat spinal cords (Tolle et al. 1993; Tolle et al. 1995; Furuyama et al. 1993), GluR2 mRNA is widely expressed in the spinal cord ventral horns and we have previously verified GluR2 mRNA expression in retrogradely-labeled PhMNs in adult rats (Gransee et al. 2017; Mantilla et al. 2012). Of note, AMPA receptors containing GluR2 subunits (encoded by the Gria2 gene) can shape synaptic currents due to their considerably slower rates of desensitization and subsequent relatively faster recovery (Seeburg 1996; Funk et al. 1995; Smith et al. 1991). Neurons expressing higher levels of AMPA receptors would thus be primed to respond rapidly to incoming inputs to that motor pool. Higher expression of AMPA receptors in smaller PhMNs (as found in the current study) is thus consistent with their more frequent and earlier activation during ventilatory behaviors (Fournier & Sieck 1988; Sieck et al. 1989; Mantilla et al. 2010).

NMDA receptors modulate longer lasting synaptic events in response to glutamate release and are non-selective cation channels allowing influx of Ca2+ together with Na+ and efflux of K+ ions (Scheetz & Constantine-Paton 1994; Michaelis 1998; Daw et al. 1993). NMDA receptors also exist as heterotetrameric structures that require that assembly of the obligatory NR1 subunits (encoded by the Grin1 gene) with either NR2(A,B,C,D) subunits or with a combination of NR2 subunits with NR3(A,B) subunits (Paoletti et al. 2013). Both NR1 and NR2A subunits have been widely observed in rat spinal cords (Luque et al. 1994; Furuyama et al. 1993; Piehl et al. 1995). We have also previously verified the presence of Grin1 mRNA expression in retrogradely labelled PhMNs in adult rats (Gransee et al. 2017; Mantilla et al. 2012). Activation of NMDA receptors removes a Mg2+ channel block increasing post-synaptic excitability (Christenson et al. 1991; el Manira et al. 1994; Durand 1991), and, given their slow receptor kinetics, provides an important substrate for temporal summation of excitatory post synaptic currents (Rekling et al. 2000). NMDA receptors can also enhance the response to and detection of synchronous inputs through non-linear synaptic integration via dendritic spikes (Funk et al. 1995). Higher density of NMDA mRNA expression in smaller PhMNs may thus contribute to their persistent activation during ventilatory behaviors even at relatively low levels of descending excitatory inputs (Fournier & Sieck 1988; Sieck et al. 1989; Mantilla et al. 2010).

The single cell multiplex analysis conducted in the present study also uniquely permits comparisons of mRNA expression for various transcripts within a motor neuron. PhMNs with smaller surface area showed the highest levels of cytosolic AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density, whereas those with larger surface show the lowest levels of cytosolic mRNA transcript density. These findings support a role for AMPA and NMDA mediated excitatory neurotransmission in the earlier recruitment of smaller PhMNs for lower force ventilatory behaviors.

AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression across neuronal compartments

Gene expression is a multi-level, highly regulated process with mRNA transcription occurring in the cell nucleus where the pre-mRNA is manufactured from the DNA template, followed by processing to a mature mRNA that is primed for export into the cytosol (Ben-Ari et al. 2010). mRNA is subsequently translocated to the cytosol for translation into proteins. Although the physiological relevance of compartmental distribution of mRNA transcripts is not fully defined, cytosolic mRNA is more closely associated with protein levels (de Sousa Abreu et al. 2009; Akan et al. 2012). Recent studies bring to attention the dilution of hybridization results when nuclear mRNA is included, and therefore promote the assessment of cytosolic mRNA levels as a more reliable indicator of translational activity for specific gene products of interest (Trask et al. 2009; Solnestam et al. 2012). The current design of RNAscope target probes determines hybridization with exons that are present in both pre-mRNA and mature mRNA. Accordingly, the RNAscope probes do not allow distinguishing between the various mRNA forms. In the present study, we examined mRNA transcript density across cytosolic and nuclear compartments in order to evaluate possible differences that would more closely reflect transcript expression differences across motor neurons of varying size. Both AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density was higher in the nucleus of PhMNs compared to the cytosol (on average, ~4 fold higher for AMPA and ~2 fold higher for NMDA), suggesting differences in the transcriptional rates for these two genes.

Once somal compartment was considered in the mixed linear models, the effect of PhMN somal surface area on AMPA and NMDA mRNA transcript density was only significant for the NMDA receptor. Specifically, the strong negative correlation between cytosolic NMDA mRNA expression and PhMN somal surface area suggests a more important role for NMDA-mediated glutamatergic neurotransmission at smaller PhMNs compared to larger neurons, and is consistent with their recruitment order. Although both AMPA and NMDA receptors have been shown to exhibit activity-dependent dendritic translation, primarily in brain regions (Bramham & Wells 2007; Kessels & Malinow 2009), it is likely that dendritic mRNA levels reflect cytosolic levels and transport into dendrites. Dendritic mRNA translation is thought to regulate neuroplasticity in response to local activation levels, and thus, it is possible that neuroplasticity within dendrites may be under additional translational control not identified in this study. Regardless, a higher density of cytosolic NMDA mRNA in smaller PhMNs (~25% greater than at large motor neurons) supports a predominant role for differences in NMDA-mediated glutamatergic neurotransmission in the recruitment order of phrenic motor units.

Differences in mRNA transcript density across motor neurons of varying size likely have implications for neuroplasticity across the motor neuron pool that are of considerable interest in in the context of conditions associated with altered glutamatergic neurotransmission including following spinal cord injury. In previous studies using laser-capture microdissection of PhMNs, we found that NMDA Grin1 mRNA expression initially decreases ipsilaterally in PhMNs at 3 days after a unilateral C2 hemisection (C2SH) injury that disrupts the primary descending excitatory inputs, but then increases at 14 days post-C2SH and 21 days post-C2SH (Mantilla et al. 2012; Gransee et al. 2017). We did not find significant changes in AMPA Gria2 mRNA expression after C2SH. However, in these previous studies, we did not stratify measurements of glutamatergic receptor expression by PhMN size. Further investigation of changes in glutamatergic receptor mRNA expression and their subunits across PhMNs in a size dependent fashion will provide valuable insight into mechanisms of injury and recovery.

Implications of differential glutamatergic receptor expression in motor behaviors

The relative contribution of AMPA vs. NMDA receptor-mediated input to PhMNs in determining phrenic motor output has previously been studied via pharmacological inhibition of these receptors at the level of the spinal cord. Using phrenic nerve recordings from in vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations in neonatal rats, various studies showed a predominant role of non-NMDA receptors (presumably AMPA receptors) in mediating glutamatergic neurotransmission to PhMNs during the inspiratory phase of eupneic breathing (Liu et al. 1990; McCrimmon et al. 1989; Greer et al. 1991). In contrast, Chitravanshi and Sapru (1996) showed a decrease in phrenic nerve amplitude in response to both AMPA and NMDA receptor blockade in spinal cord segments of adult rats using an in vivo preparation. It must be noted that these studies only test the role of AMPA and NMDA mediated neurotransmission during eupneic activity and do not test the role of these receptors in mediating PhMN activation to accomplish higher force behaviors. In the present study, we document an abundance of AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression in the entire PhMN pool, regardless of their size. Thus, the abundance of AMPA and NMDA mRNA expression in small and large PhMNs supports a role for PhMN activation via these ionotropic receptors across the full range of motor behaviors.

NMDA receptors have been implicated in producing rhythmic behaviors due to their contribution to non-linear synaptic integration at dendrites (Funk et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1998). NMDA receptors mediate voltage dependent amplification of excitation at PhMNs resulting in an oscillatory state (Enriquez Denton et al. 2012).The presence of high frequency oscillations during rhythmic ventilatory behaviors such as eupnea has been interpreted as indicating near synchronous activation of the PhMN pool (Duffin & van Alphen 1995; Parkis et al. 2003; Funk & Parkis 2002; Marchenko et al. 2012), which would be amplified by the higher expression of NMDA receptors in the smaller motor neurons responsible for lower-force ventilatory behaviors. Unfortunately, the electrophysiological studies commonly used to characterize motor unit type are not compatible with the biochemical transcript analyses conducted in the present study.

Conclusions and future directions

The primary findings of this study are that AMPA and NMDA mRNA are highly expressed in smaller PhMNs as compared to larger PhMNs. These findings are consistent with the size principle of motor unit recruitment, whereby, smaller motor neurons comprising type S and FR motor units are recruited first owing to their lower membrane capacitance and higher glutamatergic receptor expression. It is possible that motor neurons exploit the output amplifying properties of AMPA and NMDA receptors to fine tune their intrinsic excitabilities within a motor pool comprising motor neurons of varying sizes. Thus, differences in glutamatergic receptor expression may contribute to achieving highly fidelity in the responses to a diverse range of motor demands of the system, matching the fatigue characteristics of the various motor units to the task (with fatigue resistant type S and FR units being activated for repetitive behaviors such as breathing, and in contrast fatigable type FInt and FF units being activated only for infrequent, high force expulsive behaviors). Accordingly, the results of the present study provide important insight into differences in glutamatergic receptor density across motor neurons in a well-characterized motor pool revealing a potential role for glutamatergic neurotransmission in the achievement of a broad range of motor behaviors representing varying functional demands and force generation.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Dr. Heather M. Gransee, Dr. Wen-Zhi Zhan and Ms. Yun-Hua Fang for technical support. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HL96750 and R01 HL146114, and the Mayo Clinic Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- mRNA

Messenger Ribonucleic acid

- PhMN

Phrenic motor neuron

- CTB-488

Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β (CTB-488)

- RRID

Research Resource Identifier (see scicrunch.org)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akan P, Alexeyenko A, Costea PI et al. (2012) Comprehensive analysis of the genome transcriptome and proteome landscapes of three tumor cell lines. Genome Med 4, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alilain WJ and Goshgarian HG (2007) MK-801 upregulates NR2A protein levels and induces functional recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm following acute C2 hemisection in adult rats. J Spinal Cord Med 30, 346–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alilain WJ and Goshgarian HG (2008) Glutamate receptor plasticity and activity-regulated cytoskeletal associated protein regulation in the phrenic motor nucleus may mediate spontaneous recovery of the hemidiaphragm following chronic cervical spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 212, 348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Argote S, Gransee HM, Mora JC, Stowe JM, Jorgenson AJ, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2016) The Impact of Midcervical Contusion Injury on Diaphragm Muscle Function. J Neurotrauma 33, 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. a., Brody Y, Kinor N, Mor A, Tsukamoto T, Spector DL, Singer RH and Shav-Tal Y. (2010) The life of an mRNA in space and time. Journal of Cell Science 123, 1761–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR and Wells DG (2007) Dendritic mRNA: transport, translation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 8, 776–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE (1981) Motor units: anatomy, physiology and functional organization In: Handbook of Physiology. The Nervous System. Motor Control, (Peachey LD), Vol. 3, pp. 345–422. Am Physiol Soc, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, Levine DN, Tsairis P and Zajac FE 3rd (1973) Physiological types and histochemical profiles in motor units of the cat gastrocnemius. J Physiol 234, 723–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC and Sapru HN (1996) NMDA as well as non-NMDA receptors mediate the neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons in the adult rat. Brain Res 715, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson J, Alford S, Grillner S and Hokfelt T. (1991) Co-localized GABA and somatostatin use different ionic mechanisms to hyperpolarize target neurons in the lamprey spinal cord. Neurosci Lett 134, 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clamann HP (1993) Motor unit recruitment and the gradation of muscle force. Phys Ther 73, 830–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clamann HP and Henneman E. (1976) Electrical measurement of axon diameter and its use in relating motoneuron size to critical firing level. J Neurophysiol 39, 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw NW, Stein PS and Fox K. (1993) The role of NMDA receptors in information processing. Annual Review Of Neuroscience 16, 207–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Abreu R, Penalva LO, Marcotte EM and Vogel C. (2009) Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol Biosyst 5, 1512–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decima EE, von Euler C and Thoden U. (1969) Intercostal-to-phrenic reflexes in the spinal cat. Acta Physiol Scand 75, 568–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins EG and Feldman JL (1994) Brainstem network controlling descending drive to phrenic motoneurons in rat. J Comp Neurol 347, 64–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J and van Alphen J. (1995) Bilateral connections from ventral group inspiratory neurons to phrenic motoneurons in the rat determined by cross-correlation. Brain Res 694, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand J. (1991) NMDA Actions on Rat Abducens Motoneurons. European Journal of Neuroscience 3, 621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Manira A, Tegner J and Grillner S. (1994) Calcium-dependent potassium channels play a critical role for burst termination in the locomotor network in lamprey. J Neurophysiol 72, 1852–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberger HH and Feldman JL (1988) Monosynaptic transmission of respiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons from brainstem bulbospinal neurons in rats. J Comp Neurol 269, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberger HH, Feldman JL and Goshgarian HG (1990) Ventral respiratory group projections to phrenic motoneurons: electron microscopic evidence for monosynaptic connections. J Comp Neurol 302, 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enad JG, Fournier M and Sieck GC (1989) Oxidative capacity and capillary density of diaphragm motor units. J Appl Physiol 67, 620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez Denton M, Wienecke J, Zhang M, Hultborn H and Kirkwood PA (2012) Voltage-dependent amplification of synaptic inputs in respiratory motoneurones. J Physiol 590, 3067–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty MJ, Omar TS, Zhan WZ, Mantilla CB and Sieck GC (2018) Phrenic Motor Neuron Loss in Aged Rats. J Neurophysiol 119, 1852–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier M and Sieck GC (1988) Mechanical properties of muscle units in the cat diaphragm. J Neurophysiol 59, 1055–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk GD and Parkis MA (2002) High frequency oscillations in respiratory networks: functionally significant or phenomenological? Respir Physiol Neurobiol 131, 101–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk GD, Smith JC and Feldman JL (1995) Modulation of neural network activity in vitro by cyclothiazide, a drug that blocks desensitization of AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 15, 4046–4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama T, Kiyama H, Sato K, Park HT, Maeno H, Takagi H and Tohyama M. (1993) Region-specific expression of subunits of ionotropic glutamate receptors (AMPA-type, KA-type and NMDA receptors) in the rat spinal cord with special reference to nociception. Brain Research Molecular Brain Research 18, 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali MGZ (2017) The bulbospinal network controlling the phrenic motor system: Laterality and course of descending projections. Neurosci Res 121, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee HM, Gonzalez Porras MA, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2017) Motoneuron glutamatergic receptor expression following recovery from cervical spinal hemisection. J Comp Neurol 525, 1192–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee HM, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2013) Targeted Delivery of TrkB Receptor to Phrenic Motoneurons Enhances Functional Recovery of Rhythmic Phrenic Activity after Cervical Spinal Hemisection. PloS one 8, e64755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee HM, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2015) Localized Delivery of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor-Expressing Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhances Functional Recovery following Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 32, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Smith JC and Feldman JL (1991) Role of excitatory amino acids in the generation and transmission of respiratory drive in neonatal rat. J Physiol 437, 727–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JJ, Smith JC and Feldman JL (1992) Glutamate release and presynaptic action of AP4 during inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons. Brain Res 576, 355–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger IH, Watson JF and Cull-Candy SG (2017) Structural and Functional Architecture of AMPA-Type Glutamate Receptors and Their Auxiliary Proteins. Neuron 94, 713–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneman E, Somjen G and Carpenter DO (1965a) Excitability and inhibitability of motoneurons of different sizes. J Neurophysiol 28, 599–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneman E, Somjen G and Carpenter DO (1965b) Functional significance of cell size in spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 28, 560–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa AN, Zhan WZ, Sieck G and Mantilla CB (2010) Neuregulin-1 at synapses on phrenic motoneurons. J Comp Neurol 518, 4213–4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernell D. (2006) The motoneurone and its muscle fibres. Oxford University Press Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HW and Malinow R. (2009) Synaptic AMPA receptor plasticity and behavior. Neuron 61, 340–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurram OU, Fogarty MJ, Rana S, Vang P, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2018) Diaphragm muscle function following mid-cervical contusion injury in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Fuller DD, White TE and Reier PJ (2008a) Respiratory neuroplasticity and cervical spinal cord injury: translational perspectives. Trends in neurosciences 31, 538–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, White TE, Coutts MA et al. (2008b) Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. J Comp Neurol 511, 692–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KZ and Fuller DD (2011) Neural control of phrenic motoneuron discharge. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 179, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell EGT and Sherrington CS (1925) Recruitment and some other factors of reflex inhibition. Proc Roy Soc Lond (Biol) 97, 488–518. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J, Duffin J, Kruszewska B and Zhang X. (1993) Upper cervical inspiratory neurons in the rat: an electrophysiological and morphological study. Exp Brain Res 95, 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J, Zhang X, Kruszewska B and Kanjhan R. (1994) Morphological study of long axonal projections of ventral medullary inspiratory neurons in the rat. Brain Res 640, 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Feldman JL and Smith JC (1990) Excitatory amino acid-mediated transmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 64, 423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JM, Bleuel Z, Malherbe P and Richards JG (1994) Alternatively spliced isoforms of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 1 are differentially distributed within the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience 63, 629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T, Guell M and Serrano L. (2009) Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Letter 583, 3966–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Bailey JP, Zhan WZ and Sieck GC (2012) Phrenic motoneuron expression of serotonergic and glutamatergic receptors following upper cervical spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 234, 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Gransee HM, Zhan WZ and Sieck GC (2013) Motoneuron BDNF/TrkB signaling enhances functional recovery after cervical spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 247C, 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Gransee HM, Zhan WZ and Sieck GC (2017) Impact of glutamatergic and serotonergic neurotransmission on diaphragm muscle activity after cervical spinal hemisection. J Neurophysiol 118, 1732–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Seven YB, Zhan WZ and Sieck GC (2010) Diaphragm motor unit recruitment in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 173, 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Gransee HM, Prakash YS and Sieck GC (2018) Phrenic motoneuron structural plasticity across models of diaphragm muscle paralysis. J Comp Neurol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ and Sieck GC (2009) Retrograde labeling of phrenic motoneurons by intrapleural injection. J Neurosci Methods 182, 244–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko V, Ghali MG and Rogers RF (2012) Motoneuron firing patterns underlying fast oscillations in phrenic nerve discharge in the rat. J Neurophysiol 108, 2134–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrimmon DR, Smith JC and Feldman JL (1989) Involvement of excitatory amino acids in neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to spinal respiratory motoneurons. J Neurosci 9, 1910–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis EK (1998) Molecular biology of glutamate receptors in the central nervous system and their role in excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and aging. Prog Neurobiol 54, 369–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Seeburg PH and Wisden W. (1991) Glutamate-operated channels: developmentally early and mature forms arise by alternative splicing. Neuron 6, 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Bellone C and Zhou Q. (2013) NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 14, 383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkis MA, Feldman JL, Robinson DM and Funk GD (2003) Oscillations in endogenous inputs to neurons affect excitability and signal processing. J Neurosci 23, 8152–8158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl F, Tabar G and Cullheim S. (1995) Expression of NMDA receptor mRNAs in rat motoneurons is down-regulated after axotomy. European Journal of Neuroscience 7, 2101–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash YS, Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Smithson KG and Sieck GC (2000) Phrenic motoneuron morphology during rapid diaphragm muscle growth. J Appl Physiol 89, 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash YS, Smithson KG and Sieck GC (1993) Measurements of motoneuron somal volumes using laser confocal microscopy: comparisons with shape-based stereological estimations. Neuroimage 1, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash YS, Smithson KG and Sieck GC (1994) Application of the Cavalieri principle in volume estimation using laser confocal microscopy. Neuroimage 1, 325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Mantilla CB and Sieck GC (2019) Glutamatergic Input Varies with Phrenic Motor Neuron Size. J Neurophysiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Sieck GC and Mantilla CB (2017) Diaphragm electromyographic activity following unilateral midcervical contusion injury in rats. J Neurophysiol 117, 545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling JC, Funk GD, Bayliss DA, Dong XW and Feldman JL (2000) Synaptic control of motoneuronal excitability. Physiol Rev 80, 767–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers JE (1973) Extra-segmental reflexes derived from intercostal afferents: phrenic and laryngeal responses. J Physiol 233, 45–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saji M and Miura M. (1990) Evidence that glutamate is the transmitter mediating respiratory drive from medullary premotor neurons to phrenic motoneurons: a double labeling study in the rat. Neurosci Lett 115, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu MS, Dougherty BJ, Lane MA, Bolser DC, Kirkwood PA, Reier PJ and Fuller DD (2009) Respiratory neuroplasticity following high cervical hemisection. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheetz AJ and Constantine-Paton M. (1994) Modulation of NMDA receptor function: implications for vertebrate neural development. FASEB J 8, 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BJ, Hochman S and MacLean JN (1998) NMDA receptor-mediated oscillatory properties: potential role in rhythm generation in the mammalian spinal cord. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 860, 189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg PH (1996) The role of RNA editing in controlling glutamate receptor channel properties. J Neurochem 66, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC, Fournier M and Enad JG (1989) Fiber type composition of muscle units in the cat diaphragm. Neuroscience Letters 97, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DO, Franke C, Rosenheimer JL, Zufall F and Hatt H. (1991) Desensitization and resensitization rates of glutamate-activated channels may regulate motoneuron excitability. J Neurophysiol 66, 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnestam BW, Stranneheim H, Hallman J, Kaller M, Lundberg E, Lundeberg J and Akan P. (2012) Comparison of total and cytoplasmic mRNA reveals global regulation by nuclear retention and miRNAs. BMC Genomics 13, 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Q and Goshgarian HG (1996) Ultrastructural quantitative analysis of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic terminals in the phrenic nucleus after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol 372, 343–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G-F and Duffin J. (1996a) Connections from upper cervical inspiratory neurons to phrenic and intercostal motoneurons studied with corss-correlation in the decerebrate rat. Exp Brain Res 110, 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian GF and Duffin J. (1996b) Spinal connections of ventral-group bulbospinal inspiratory neurons studied with cross-correlation in the decerebrate rat. Exp Brain Res 111, 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolle TR, Berthele A, Zieglgansberger W, Seeburg PH and Wisden W. (1993) The differential expression of 16 NMDA and non-NMDA receptor subunits in the rat spinal cord and in periaqueductal gray. J Neurosci 13, 5009–5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolle TR, Berthele A, Zieglgansberger W, Seeburg PH and Wisden W. (1995) Flip and Flop variants of AMPA receptors in the rat lumbar spinal cord. European Journal of Neuroscience 7, 1414–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask HW, Cowper-Sal-lari R, Sartor MA et al. (2009) Microarray analysis of cytoplasmic versus whole cell RNA reveals a considerable number of missed and false positive mRNAs. RNA 15, 1917–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ et al. (2010) Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacology Review 62, 405–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Sakimura K and Mishina M. (1992) Developmental changes in distribution of NMDA receptor channel subunit mRNAs. Neuroreport 3, 1138–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]