Abstract

MicroRNAs are short, (18–22 nt) non-coding RNAs involved in important cellular processes due to their ability to regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Exosomes are small (50–200 nm) extracellular vesicles, naturally secreted from a variety of living cells and are believed to mediate cell-cell communication through multiple mechanisms, including uptake in destination cells. Circulating microRNAs and exosome-derived microRNAs can have key roles in regulating muscle cell development and differentiation. Several microRNAs are highly expressed in muscle and their regulation is important for myocyte homeostasis. Changes in muscle associated microRNA expression are associated with muscular diseases including muscular dystrophies, inflammatory myopathies, and congenital myopathies. In this review, we aim to highlight the biology of microRNAs and exosomes as well as their roles in muscle health and diseases. We also discuss the potential crosstalk between skeletal and cardiac muscle through exosomes and their contents. skeletal and cardiac muscle through exosomes and their contents.

Keywords: exosomes, microRNAs, neuromuscular disease, skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, (18–22 nt) non-coding RNAs, which contribute to the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and are implicated in several normal developmental and physiological processes, including skeletal muscle development, and regeneration (Aoi W, and Sakuma K, 2014). Dysregulated miRNAs are associated with muscle disease and myopathy, making them attractive candidates for biomarker development or potential therapeutic targets (Wang H, and Wang B, 2016). MiRNAs are secreted from the cells in a stabilized form either bound to proteins such as Argonaute 2 (AGO2) or within extracellular vesicles such as exosomes. Exosomes and their associated miRNAs play a role in cell-to-cell communication which could either be communication between neighboring cells or distant cells in a different organ. In this review, we will give an overview of circulating and exosomal miRNAs, their role in normal myocyte development, and how perturbation of their expression has been associated with muscle disease processes.

I. MiRNAs

I.1. MiRNA biogenesis and functional regulation of gene expression

MiRNA is transcribed from genes by RNA polymerase II into a miRNA hairpin precursor. This hairpin precursor is then processed by the RNAse III endonuclease, Drosha, into a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Lee Y et al., 2002). Exportin5 escorts the pre-miRNA into the cytoplasm where it undergoes further processing by Dicer to become a mature, single-stranded miRNA. Mature miRNA can be loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) for degradation of target mRNA, or it may be loaded into extracellular vesicles, such as exosomes to stimulate paracrine or endocrine signaling (Zhang D et al., 2017).

MiRNAs primarily regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding a complementary ‘seed’ sequence in the 3’ UTR of target mRNAs (Yang JS et al., 2011; He L, and Hannon GJ, 2004; Lagos-Quintana M et al., 2001). Each miRNA is thought to have hundreds of mRNA targets and thus, they are part of a vast network regulating diverse physiological processes including cell development, cell signaling, and cell death (Tang Y et al., 2009). MiRNAs down-regulate gene expression by either blocking translation or destabilizing the mRNA to cause mRNA decay (Wahid F et al., 2010). Functional effects of miRNAs have been described in numerous muscle pathologies and will be discussed in detail later in this review (Cacchiarelli D et al., 2011; Wahid F et al., 2010; Iwakawa H, and Tomari Y, 2015; Sohel MH, 2016).

MiRNAs regulate gene expression to maintain normal physiology and consequently, human pathologies such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and neuromuscular diseases have been found to correlate with altered expression levels of miRNAs (Eisenberg I et al., 2007; Feng J et al., 2016; Zhou SS et al., 2018; Peng Y, and Croce CM, 2016). Therefore, it is necessary for cells to have strict regulation of miRNA expression, activity, and stability in order to maintain cellular homeostasis (Krol J et al., 2010; Rüegger S, and Großhans H, 2012). MiRNA expression is regulated at the level of transcription or by destabilization and degradation of the mature miRNA leading to an overall decrease in abundance (Rissland OS et al., 2011; Avraham R et al., 2010; Bail S et al., 2010). Furthermore, mature miRNA activity is also subject to regulation (Lai EC et al., 2004; Chen PS et al., 2011). Currently, the process of how disease states may regulate expression and activity of miRNAs is unknown.

I.2. MiRNAs in muscle health, development, and disease

MiRNA-mediated regulation of myogenesis

MiRNAs are essential for myogenesis and maintenance of normal myocyte health, as conditional inactivation of Dicer in the skeletal muscle decreased expression of miRNA-1, −133, and −206, leading to skeletal muscle hypoplasia and perinatal lethality due to defective morphogenesis and maintenance of myofibers (O’Rourke JR et al., 2007). Numerous miRNAs are ubiquitously expressed, however, those highly enriched in skeletal and cardiac muscle are termed “myomiRs” (Diniz GP, and Wang DZ, 2016; Chen JF et al., 2006). Common myomiRs include miRs- 1, −133a/b, −206, −208a/b, −486, and −499 (van Rooij E et al., 2009; van Rooij E et al., 2007; Small EM et al., 2010; McCarthy JJ, 2008; Sempere LF et al., 2004).

MiRNAs have important regulatory roles in myogenesis. Myogenesis is the complex process of developing myoblasts into muscle tissue, and involves multiple stages of differentiation and proliferation which are controlled by myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) (Pownall ME et al., 2002; Sartorelli V, and Caretti G, 2005). MRFs include MyoD, Myf5, myogenin and MRF4, and they control myocyte-specific gene expression and myomiR expression in order to induce proliferation and myogenic commitment (Berkes CA, and Tapscott SJ, 2005; Sweetman D et al., 2008; Rao PK et al., 2006; Tajbakhsh S et al., 1998; Rhodes SJ, and Konieczny SF, 1989; Wright WE et al., 1989).

Several studies show the differential expression of miRNAs during the different stages of myogenesis (Iwasaki H et al., 2015; Goljanek-Whysall K et al., 2011; Goljanek-Whysall K et al., 2012; Townley-Tilson WH et al., 2010). For example, non-myocyte specific miRNAs such as miR-27a, are known to induce proliferation by reducing expression of myostatin, an inhibitor of myogenesis, and to induce differentiation by repression of Pax3 (Crist CG et al., 2009; Ríos R et al., 2002; Chen X et al., 2013; Huang Z et al., 2012). Tissue specific myomiRs also have important roles in myogenesis. While myomiRs −1 and −133 are transcribed together, they each function separately in the regulation of myocyte proliferation and differentiation. MiR-133 suppresses serum response factor, thereby inhibiting myoblast proliferation, whereas miR-1 directs proliferation through inhibition of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), which in turn allows for transcription of proliferative genes via MyoD (Chen JF et al., 2006; Liu N et al., 2008). Furthermore, miR-208b and miR-499 influence myofiber type by regulating expression of genes to induce fast or slow type myofibers (van Rooij E et al., 2009). Differentiation of myocytes is promoted by miRs-206 and −486 by downregulating Pax7, a factor which inhibits MyoD (Dey BK et al., 2011). Interestingly, myomiRs-1 and −133 are found to be dysregulated in a majority of muscle diseases (Table 1), suggesting that alteration of their expression is sufficient to impair muscle homeostasis. Whether the dysregulation of myomiRs-1 and −133 is causative of, or the result of pathological processes in muscle is still under investigation.

Table 1:

Muscle disease-associated miRNAs and associated phenotypes

| Disease | miRNA(s) dysregulated |

Source | Associated phenotype(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker muscular dystrophy |

miR-146b miR-221 |

Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

| 7 miRNAs | Human BMD muscle samples | • Increased expression associated with age and disease severity • TNF-α stimulates miR-146b, miR-374a, miR-31 |

(Fiorillo AA et al., 2015) | |

|

miR-1 miR-133a miR-206 |

Human serum, mdx serum | Increased expression associated with elevated CK levels | (Matsuzaka Y et al., 2014) | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

miR-1 miR-29 miR-206 |

mdx tissue, DMD myotubes | • Altered miRNAs alters cellular redox state via G6PD • Associated with fibrosis and aberrant satellite stem cell differentiation |

(Cacchiarelli D et al., 2010) |

|

miR-21 miR-29 |

Human DMD muscle biopsies, mdx tissue | • Associated with increased collagen production via PTEN and SPRy-1 • Overexpressing miR-29 decreases collagen markers |

(Zanotti S et al., 2015) | |

|

miR-1 miR-133 miR-206 miR-222 miR-486 |

GRMD dog muscle tissue | • MiRs-486/206 localized to regenerated muscle fibers; • Stem cell delivery stimulates miR-133 • miRNA targeting of MHC and MYH7 |

(Robriquet F et al., 2016) | |

| 11 miRNAs | mdx tissue, human DMD biopsies, C2C12 myoblasts | • MiRs-31, −34c, −206, −335, −449 and −494 were associated with myocyte regeneration • Downregulation of miRs-1, −29c, −135a were associated with myofiber loss and fibrosis • MiRs-222, −223 were expressed in areas of inflammation |

(Greco S et al., 2009) | |

|

miR-1a mIR-133a miR-206 |

mdx tissue | Overexpressing miR-133a restores normal mdx skeletal musculature and cardiac morphology | (Deng Z et al., 2011) | |

| 32 miRNAs | Human DMD serum, mdx serum | miRs-1, −133a, −133b and −206 were enriched in aged mdx samples | (Vignier N et al., 2013) | |

| Myotonic dystrophy |

miRs-1 miR-133a miR-133b miR-206 |

Human serum | Associated with progressive muscle wasting | (Koutsoulidou A et al., 2015) |

| 10 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | • Dysregulated miRNAs associated with atrophy and hypertrophy index in type 2 myofibers; • Association with various signaling pathways |

(Greco S et al., 2012) | |

| miR-206 | Human muscle biopsies | miR-206 overexpression was associated with areas of centralized nuclei | (Gambardella S et al., 2010) | |

| 9 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | • MiR-133b was higher in female patients; • Dysregulated miRNAs associated with skeletal muscle strength and CK levels; • Dysregulated miR-1 and miR-29 associated with upregulation of predicted gene targets |

(Perbellini R et al., 2011) | |

| 54 miRNAs | Human DM1 and mouse heart tissue samples | • Dysregulated miRNAs associated with cardiac arrhythmias and fibrosis, and with MEF2 dysregulation • Knockdown of MEF2 revealed miRNAs directly regulated |

(Kalsotra A et al., 2014) | |

|

miR-29b miR-29c miR-33a miR-133a |

Human blood and muscle biopsies | n/a | (Ambrose KK et al., 2017) | |

| Limb girdle muscular dystrophy |

Type 2A: 88 miRNAs |

Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

|

Types 2A/2B: miR-1 miR-133a miR-206 |

Human serum | n/a | (Matsuzaka Y et al., 2014) | |

|

Type 2B: 87 miRNAs |

Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) | |

| Unknown type: 53 miRNAs | Human serum, Sgca-null and Sgcg-null mice | Associated with elevated leukocytes and platelets, but not erythrocytes | (Vignier N et al., 2013) | |

| Fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy | 62 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) | |

|

miR-1 miR-133a miR-206 |

Human serum | n/a | (Matsuzaka Y et al., 2014) | |

| 8 miRNAs | Fetal human muscle biopsies | Various miRNAs displayed altered expression during muscle development | (Portilho DM et al., 2015) | |

| 29 miRNAs | Human myoblasts | Dysregulated miRNAs associated with DUX4c levels | (Dmitriev P et al., 2013) | |

| Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy |

miR-1 miR-133a/b miR-2–6 |

Human serum | n/a | (Zaharieva IT et al., 2013) |

| Myoshi myopathy | 69 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

| Nemaline myopathy | 53 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

| 19 miRNAs | Cofilin-2 deficient mouse muscle tissue | Dysregulated miRNAs associated with loss of cell cycle checkpoint regulation which hinders muscle regeneration | (Morton SU et al., 2015) | |

| Polymyositis /Dermatomyositis | 37 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

| miR-4442 | Human plasma | Therapy restores miR-4442 to levels comparable to healthy controls | (Hirai T et al., 2018) | |

| miR-381 | Human blood samples, mouse tissue | miR-381 was associated with reduction of inflammation and macrophage infiltration via HMGB1 | (Liu Y et al., 2018) | |

| 39 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | Endurance exercise altered miRNAs, decreased IKBKB was associated with increased miR-196b and increased AK3 and HIBADH (mitochondrial proteins) | (Boehler JF et al., 2017) | |

| miR-146a | Human muscle biopsies, SD rats | Increased miR-146a decreased inflammation via downregulating TRAF5, IL-17 and ICAM-1 | (Yin Y et al., 2016) | |

| Inclusion body myositis | 20 miRNAs | Human muscle biopsies | n/a | (Eisenberg I et al., 2007) |

|

miR-1 miR-133 miR-206 |

Human muscle biopsies | Associated with increased expression of inflammatory cytokines | (Georgantas RW et al., 2014) |

MiRNAs are involved in muscle regeneration

Not only do miRNAs have essential roles in regulating gene expression during myogenesis, they are also involved in muscle regeneration (Galimov A et al., 2016; Nie M et al., 2016). Distinct patterns of miRNA expression have been observed in murine cardiac progenitor cells, suggestive of their diverse regulatory roles at different points during regeneration (Chen Y et al., 2011). Chen et al. went on to demonstrate that elevated miR-351 actively promoted progenitor cell proliferation and survival via inhibition of E2F3, which protected cells from apoptosis following injury (Chen Y et al., 2012). MyomiR-206 is described above as having roles in proliferation and differentiation, and it has also been shown to promote regeneration in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Liu N et al., 2012). These studies are important for identifying potential therapeutic targets to modulate in muscle diseases such as the muscular dystrophies, where myocyte regeneration is known to be impaired (Luz MA et al., 2002).

Dysregulation of miRNAs in primary muscle diseases

The involvement of miRNAs in developmental processes suggests that they may modulate other cellular processes including disease pathogenesis. Disease pathogenesis of many primary muscle diseases, including congenital and non-congenital muscular dystrophies, and inflammatory and non-inflammatory myopathies remain important topics of active research (Sayed-Zahid AA et al., 2019; Liu C et al., 2019; Amoasii L et al., 2018; Umezawa N et al., 2018; Hu YY et al., 2018). Dysregulation of miRNAs is observed in a variety of primary skeletal muscular diseases including Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD), Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD), myotonic dystrophy, and other inflammatory and non-inflammatory myopathies. These findings, as well as their associated phenotypes, are summarized in Table 1.

Levels of miRNA expression show promise as biomarkers, suitable for tracking disease progression. In myotonic dystrophy type 1 (MD), elevated serum levels of miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b, and miR-206 serum levels were detected in patients with progressive MD in contrast to patients with stable MD, indicative of increased muscle wasting and weakness (Koutsoulidou A et al., 2015). In DMD exon-skipping treatment studies, miRNA levels corresponded to dystrophin restoration levels, muscle strength, function, and quality of life, emphasizing the utility of miRNAs not only in identifying disease progress, but also in evaluating patient responsiveness to specific therapies (Cacchiarelli D et al., 2010; Zaharieva IT et al., 2013; Hu J et al., 2014). While these findings may translate to specific muscular dystrophies, one study by Zaharieva et al., found higher levels of miRs-1, −133a,b, and −206 in DMD patient sera which corresponded with disease severity, but these levels remained unchanged in UCMD patients, highlighting disease-specific alterations in miRNA levels (Zaharieva IT et al., 2013). For future investigation of miRNAs as biomarkers of muscle disease, it will be important to take into account the patient’s specific clinical diagnosis and disease severity in order to sort out differences in expression levels. Much of the current knowledge regarding miRNAs in muscle diseases centers around the non-congenital muscular dystrophies and myopathies (Table 1). Whether miRNAs may have a role in congenital muscular dystrophies, other than UCMD remains unknown (Zaharieva IT et al., 2013).

Since aberrant miRNA levels have been found in a variety of primary muscle diseases (Table 1), it is important to identify whether the expression levels are merely a by-product of the disease state, or whether they are further contributing to pathology. In support of a pathological role for dysregulated expression levels, manipulating miRNAs in DMD and FSHD to restore healthy levels of expression was shown to improve muscle phenotypes (Alexander MS et al., 2014; Harafuji N et al., 2013; Liu N et al., 2012). Further, Fiorillo et al. demonstrated that in BMD, inflammation induced the production of detrimental miRNAs, which exacerbated the disease phenotype, suggestive of their contribution to disease pathogenesis (Fiorillo AA et al., 2015). Bioinformatic analyses of dysregulated miRNAs identified in muscle biopsies from patients with ten different primary muscle diseases revealed associations with cellular processes including signaling, motility, and metabolism highlighting potentially important cellular pathways that may be altered by miRNAs as a consequence of the disease process (Eisenberg I et al., 2007). Future work is needed to validate these findings in in vivo and in vitro models of muscle diseases.

II. Extracellular vesicles

Extracellular vesicles are membrane bound particles, including exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, which can be differentiated based on size, content, and route of formation. Exosomes (25–200 nm) contain internal cargo such as miRNA, proteins, lipids, and mRNAs. Exosomal miRNAs are of particular interest, as they have been shown to mediate myogenesis, maintain health, and have been identified in muscle disease (Forterre A et al., 2014; Hergenreider E et al., 2012; Marinho R et al., 2018).

II. 1. Exosomes in muscle health

Exosome biogenesis, release and uptake

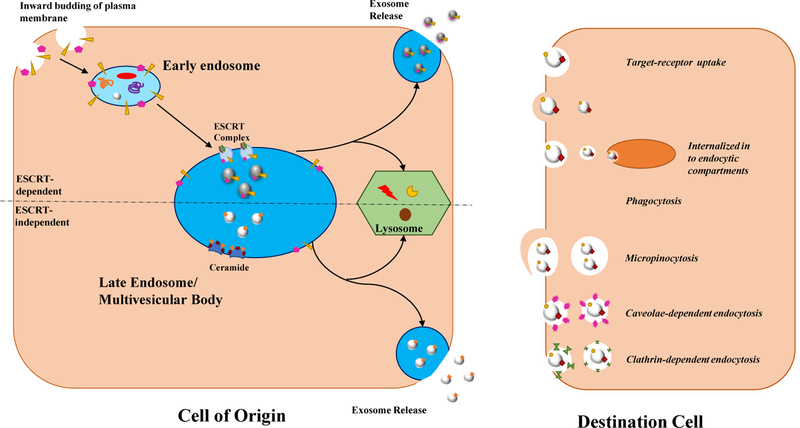

Exosomes are nanosized vesicles, identified by their cup-like morphology using electron microscopy and characteristic membrane proteins including tetraspanins, CD81, and CD63 (Mittelbrunn M et al., 2011). Exosomes originate within the endocytic pathway by inward budding of the endosomal membrane creating intraluminar vesicles (ILVs) inside maturing endosomes (Figure 1) (Abels ER, and Breakefield XO, 2016; Hurley JH, 2008; Denzer K et al., 2000). Together, these are termed multivesicular bodies (MVB) and can either travel to the lysosome or merge with the plasma membrane to release ILVs as exosomes (Bobrie A et al., 2011). The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery is involved in the formation of ILVs by driving bud formation and scission along with cargo sorting and clustering (Kowal J et al., 2014; Juan T, and Fürthauer M, 2018). Additionally, there is evidence to suggest exosome formation and cargo selection can be ESCRT independent (Juan T, and Fürthauer M, 2018). Exosome release occurs when MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane to release exosomes into the extracellular space, and whether this is a constitutive process, highly regulated, or a combination is still a matter of debate (Figure 1) (Villarroya-Beltri C et al., 2014; McKelvey KJ et al., 2015). Cells secrete a heterogenous population of exosomes of varying sizes and content, may be modulated in by ceramide synthesis (Colombo M et al., 2013). While exosomes can circulate around to various tissues, uptake may depend upon destination cell type and exosomal size (Caponnetto F et al., 2017; Salem KZ et al., 2016). Endocytosis of exosomes occurs by fusion, phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, caveolae-dependent endocytosis, and clathrin-mediated endocytosis, (Figure 1) and is mediated by adhering to target cell receptors, such as tetraspanins (Mulcahy LA et al., 2014). Once taken up, exosomes and their cargo can exert their effects in the destination cell.

Figure 1: Schematic of exosome biogenesis, release and uptake.

Exosome biogenesis is an ESCRT-dependent or independent process. For the ESCRT dependent process, the plasma membrane buds inward and internalizes surface proteins into the early endosome. The early endosome matures into the late endosome and the ESCRT complexes help sort contents into the inward budding vesicles (exosomes) in the MVB. The ESCRT-independent process involves ceramide in its formation and also buds inward into the MVB for exosome formation. The MVB from both formation methods goes to the lysosome for degradation or to the plasma membrane to release exosomes into the extracellular space. The exosomes in the extracellular space are taken up by the target cells by various methods, which allow them to transport their contents.

The biological functions of exosomal cargo and composition

Exosomes have roles in immune responses, inflammation, homeostasis, and intercellular communication (Bobrie A et al., 2011; Fujita Y et al., 2014). Exosomes mainly function in a paracrine fashion via integrin interactions, receptor-ligand interactions, and by transporting of their cargo to modulate cell signaling and gene expression (Clayton A et al., 2004; Rabinowits G et al., 2009). It is proposed exosomes are able to stimulate biological effects through both their interactions and cargo, one of these being within muscle tissue (He C et al., 2018; Théry C et al., 2009).

Exosomal and other circulating miRNAs

Circulating miRNAs have been identified in a variety of body fluids including blood and urine, and are protected from RNAse degradation by binding to proteins or lipids or by being encapsulated within extracellular vesicles (Canfrán-Duque A et al., 2016; Turchinovich A et al., 2011; Sohel MH, 2016; Mitchell S et al., 2008). Extracellular miRNA transportation may relate to the type of miRNA being transported or the cell type originated from (O’Brien J et al., 2018). This may effect the if the miRNAs uses a vesicle associated transport versus protein-bound. It is unknown which miRNA transport system is the most abundant; regardless, these circulating miRNAs may play a role in endocrine signaling between organs and are promising noninvasive disease biomarkers due to their ease of accessibility (O’Brien J et al., 2018; Siracusa J et al., 2018).

Two well-known molecular transport mechanisms for circulating miRNAs include AGO2 and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). Circulating AGO2-miRNA complexes have been identified for their involvement in numerous cellular processes including regulation of growth factors, cell proliferation, and cell migration (Prud’homme GJ et al., 2016). Circulating HDL-miRNA complexes are shown to be biomarkers for coronary artery disease, and HDL-miR-223 can reduce inflammation by inhibiting intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Canfrán-Duque A et al., 2016; Michell DL, and Vickers KC, 2016; Tabet F et al., 2014; Niculescu LS et al., 2015; Sohel MH, 2016). Circulating miRNAs have a high potential as biomarkers, and are seen to impact cellular health and disease.

Exosome-associated miRNA is another major transport mechanism in cell-to-cell communication (Diniz GP, and Wang DZ, 2016). Circulating exosomal miRNAs have been implicated in muscle injury, but also the miRNA cargo of exosomes differs in healthy versus injured skeletal muscle (Bittel DC, and Jaiswal JK, 2019). Furthermore, dystrophic-associated muscle damage and eccentric muscle damage are associated with different extracellular vesicles (Bittel DC, and Jaiswal JK, 2019). Even though it is well established exosomal associated miRNA change in response to muscle conditions, it is unknown how specific miRNAs are selectively sorted into exosomes (Bittel DC, and Jaiswal JK, 2019). However, the changes in exosomes associated miRNA in muscle-specific disorders has led to using exosomal miRNAs as potential disease biomarkers and may contribute to the understanding of disease progression.

Exosomes in muscle health

Exosomes are important for maintaining muscle health via autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine signaling (De Gasperi R et al., 2017). Exosomal communications can be influenced by factors such as stress and exercise, which in turn is thought to influence miRNA cargo loading (D’Souza RF et al., 2018). During physical activity, contracting muscle cells need to communicate with one another and exosomes are one way to promote this communication, specifically through miRNAs (Demonbreun AR, and McNally EM, 2017; Trovato E et al., 2019). Exosomal myomiR-206 assists with maintaining muscle homeostasis (Spinazzola JM, and Gussoni E, 2017). Notably, the exosomal surface proteome has an important role in muscle health. During muscle repair, exosomes are proposed to be up taken faster than other types of extracellular vesicles, such as ectosomes, due to the markers expressed, and therefore miRNA delivery can be more efficient (Bittel DC, and Jaiswal JK, 2019).

Many different cell types release exosomes which can promote skeletal muscle health and repair. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) derived exosomes can promote myogenesis of C2C12 cells in vitro (Nakamura Y et al., 2015). In this study, MSC-derived exosomes increased the total nuclear number and fusion dindices of the C2C12 cells as well as increased the expression of myogenic marker genes such as MyoG and MyoD1. MSC-exosomes also promoted muscle regeneration after cardiotoxin induced muscle injury in mice. The MSC-exosomes increased the number of myofibers and capillary density and reduced fibrosis. The levels of myomiRs including miR-1, miR-133 and miR-206 were increased in the MSC-exosomes and the local injection of these miRs have also been shown to accelerate muscle regeneration, suggesting that the regenerative effects of MSC-exosomes may be related to its miR cargo (Nakasa T et al., 2010). Exosomes isolated from differentiating human skeletal myoblasts (HSkM) in vitro were shown to facilitate myogenesis of human adipose stem cells in a concentration dependent manner, although high concentrations promoted apoptosis. This suggests a physiologic concentration is necessary for exosome-mediated myogenesis (Choi JS et al., 2016). The differentiated HSkM exosomes up-regulated the skeletal myogenesis related genes (ACTA1 and MYOD1), muscle autocrine signaling related genes (FGF2 and TNF) and muscle contractility genes (DAG1, DES, MYH1/2, TNNC1 and TNNT3). The HSkM exosomes were also able to increase expression of the terminal differentiation markers MYOD1, ACTA1, DAG1, DES, MYH1, MYH2, and TNNT1. Furthermore, the differentiating HSkM exosomes contributed to muscle regeneration in vivo after direct injection into a lacerated hindlimb muscle site in mice (Choi JS et al., 2016). In this study, exosome injection promoted the growth and maturity of regenerated myofibers and decreased the amount of inflammation and fibrosis at the site. Skeletal muscle-derived exosomes also regulate endothelial cell function by mediating angiogenesis in a VEGF independent manner (Nie Y et al., 2019). The skeletal muscle derived exosomes were enriched in angiogenic miRNAs including miR-130a. In vivo, oxidative skeletal muscle, characterized by its increased oxidative capacity and capillarization, displays evidence of increased exosome production which suggests a potential relationship between exosome production and capillarization. In other words, there is growing evidence that skeletal muscle derived exosomes regulate capillarization in skeletal muscle (Nie Y et al., 2019). Another study looked at the effects of CD34+ exosomes from mononuclear cells shown to be pro-angiogenic, when injected into the damaged hindlimbs of mice were able to improve perfusion in ischemic hind limbs, improved motor function, less tissue death and better capillary density (Mathiyalagan P et al., 2017). The route of injection is important to control where exosomes may be distributed and direct injection may allow for more specific tissue types to be targeted; however direct injection to all muscle types or muscles such as the diaphragm may not be practical for exosome-mediated therapies (Wiklander OP et al., 2015). In addition, the specific cell type that the exosomes are secreted from and their cell-type specific markers may also influence how well they are taken up into a recipient cell (Wiklander OP et al., 2015). In the future, exosomes that have been engineered to contain specific miRNAs or surface markers to may aid in their uptake and facilitate myogenesis and regeneration (Demonbreun AR, and McNally EM, 2017). More studies are needed to investigate the honing of exosomes to specific cell types in order to translate these findings into specific therapies.

II. 2. Exosomes in muscle disease

Do exosomes have protective or pathologic role?

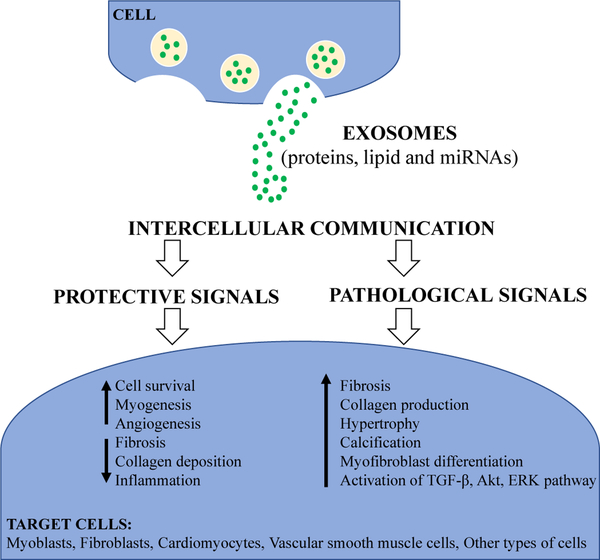

While exosomes are constantly released in physiological and pathological conditions mediators of cell communication (Figure 2), it remains unclear whether exosomes exert protective or pathogenic signals, as well as what mechanisms mediate these effects. Physiological and pathological conditions may influence exosomal cargo and composition, which ultimately exert different functional responses in target cells. Further understanding of how the quality and quantity of exosomes are controlled and the determinants of packaging the internal cargo will be of fundamental importance in exosomal biology as well as the therapeutic application of exosomes (Gangoda L et al., 2015; Ailawadi S et al., 2015).

Figure 2: Summarizing the role of exosomes in muscle health and disease.

Exosomes are released by cells and serve as mediators of cell-to-cell communication. Their cargo contents, including proteins, lipid and miRNAs, can be altered depending on the conditions that the cells experience. These exosomal cargo and composition can exert either protective or pathogenic signals on target cells.

Growing evidence suggests that exosomes mediate pathogenic effects in muscle diseases, such as the muscular dystrophies, due in part to alterations in their miRNA cargo (Ailawadi S et al., 2015). In vitro, exosomes derived from DMD fibroblasts induced trans-differentiation of wild-type fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, elevated expression levels of fibrosis markers such as transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-P1), and increased collagen production. In vivo, injection of DMD fibroblast-derived exosomes led to excessive skeletal muscle fibrosis and these effects were contributed to elevated levels of miR-199a-5p found in DMD exosomes (Zanotti S et al., 2018).

Exosomes may also have pathological roles in the development of cardiovascular diseases. Serum exosomes obtained from pediatric patients with dilated cardiomyopathy led to increased expression hypertrophy-related genes, including atrial natriuretic factor and B-type natriuretic peptide in primary cardiomyocytes. However, since this study did not characterize exosomal cargo, it is unknown whether these effects were mediated by miRNA or other cargo (Jiang X et al., 2017). Cardiac fibroblasts exosomes have been shown to be enriched with miR-21 and are capable of transferring miR-21 to neighboring cells. When neonatal cardiomyocytes were exposed to these cardiac fibroblast exosomes in vitro, there was a significant increase in cardiomyocyte cell size. These effects were mediated by miR-21 silencing of sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 2 PDZ and LIM domain 5 (Bang C et al., 2014). Taken together, these studies suggest that exosomes released from diseased cells may elicit detrimental effects on recipient cells.

In contrast, other studies have found protective roles for exosomes in the context of muscle disease and injury. Serum exosomes derived from mdx mice promoted cell survival and reduced cell death via the suppression of apoptosis-associated genes targeted by miR-133a in C2C12 myoblasts (Matsuzaka Y et al., 2016). Further, C2C12 myoblast-derived exosomes were engineered to overexpress myomiRs- 1, −133a, and −206 which enhanced survival of C2C12 myoblasts, suggesting that the miRNA cargo from the exosomes exerted beneficial effects in vitro (Matsuzaka Y et al., 2016). Exosomes isolated from either dysferlin-expressing myotubes or human serum were able to transport functional dysferlin protein into dysferlin-deficient H2K cells to assist with membrane repair (Dong X et al., 2018). In a murine model of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2I (LGMD), engineered fukutin related protein (FKRP) satellite cells were found to secrete FKRP-positive exosomes which promoted systemic FKRP expression and improved muscle recovery of FKRP-L276IKI transplanted mice (Frattini P et al., 2017). Significant reduction in collagen deposition and increase in number of regenerated myofibers were observed after exosomes were injected into a lacerated leg muscle of a muscle injury mouse model. These exosomes contained myogenic factors including insulin-like growth factors, hepatocyte growth factor, fibroblast growth factor-2, and platelet-derived growth factor-AA, which aided in muscle regeneration (Choi JS et al., 2016). Similarly, injection of exosomes secreted by human cardiosphere-derived cells into mdx mice showed increased myofiber proliferation and muscle regeneration along with decreased inflammation and fibrosis. Although a transiently restored partial expression of full-length dystrophin was observed in mdx mice, it could not be established if this minor restoration of dystrophin protein was responsible for exosome-mediated muscle regeneration or other exosome-associated cargo such as miRNA played a role (Aminzadeh MA et al., 2018). In another study, intramyocardial injection murine cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes into mouse myocardium immediately after induction of ischemia decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis by more than 50% when compared to control. These cardiac progenitor cell- derived exosomes were enriched in miR-451 but not miR-144 (Chen L et al., 2013). MiRNA-451 was reported to have a protective effect against simulated ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte death, suggesting it could be a potential target for cardioprotection in patients with high risk of ischemic attack (Zhang X et al., 2010). It is worth noting that exosome-mediated benefits may be dependent on cell type of origin. For instance, exosomes secreted by cardiac progenitor cells were more cardioprotective than exosomes released from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells, and exosomes secreted from human dermal fibroblasts had no protective effects on cardiomyocyte apoptosis and scar size (Barile L et al., 2018; Barile L et al., 2014). Exosomes play a role in muscle cell regeneration and can also be responsible transporting messages in a diseased state.

Exosomes alter cell signaling in muscle diseases

The extent to which exosomes interact with and modulate intracellular signaling pathways in the target cells is not completely understood. Exosomes can activate downstream signaling cascades in target cells by delivering signaling molecules to modulate phenotypes. A recent study showed exosomal surface proteins were required to activate ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyocytes to protect against stress-induced injury (Gartz M et al., 2018). Similarly, exosomal heat shock protein (hsp) 70 was found to protect cardiomyocytes against ischemia and reperfusion through activation of ERK1/2 and p38MAPK, leading to activation of the cardioprotective hsp27 (Vicencio JM et al., 2015).

Recent evidence suggests that exosome uptake activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling pathway by mediating the intercellular transfer of key molecules. Several proteins involved in PI3K/Akt signaling were identified in exosomes, such as phosphorylated mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), Akt, phosphoinositide-dependant kinase proteins, latent membrane protein 1, and epidermal growth factor receptor among others (Gangoda L et al., 2015). It has been shown that perfusion of purified exosomes through aortic root of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injured mice increased the phosphorylation of Akt, a known activator of survival pathways, while at the same time inhibited pro-apoptotic signaling (Arslan F et al., 2013). Exosome-mediated signaling that occurs during pathologic processes in muscle disease remains poorly understood and merits further studies. Understanding the factors that affect exosome cargo loading (i.e. disease state, injury, and other stressors) and how exosomes trigger phenotypic responses in recipient cells may shed more light into their therapeutic application for musculoskeletal diseases.

Exosomes as mediator in the cardio-skeletal muscle communication

Crosstalk between heart and skeletal muscle has been observed, as patients with advanced heart failure have been shown to develop skeletal muscular atrophy disproportionate to their decreased activity level (Callahan DM, and Toth MJ, 2013). Skeletal and cardiac muscle crosstalk may occur through exosomes that are transported through circulation and delivered to other muscle groups or distant organs (Wang H, and Wang B, 2016). For instance, exercise increases exosome release into circulation, and these exercise-induced exosomes protect the heart against ischemia and reperfusion injury (Fruhbeis C et al., 2015; Bei Y et al., 2017). Running-induced exosomes had 12 miRNAs differentially expressed which were thought to target genes in the MAPK signaling pathway (Oliveira GP Jr et al., 2018). The MAPK pathways have been involved in different aspects of cardiac regulation including development, function, and diseases. These pathways play important but yet complex role in the heart as they exhibit both protective and detrimental effects (Rose BA et al., 2010; Wang Y, 2007).

Several types of neuromuscular diseases are associated with significant cardiovascular involvement and these patients are predisposed to either cardiomyopathy and/or cardiac arrhythmias (Verhaert D et al., 2011; Beynon RP, and Ray SG, 2008). Exosomes derived from cardiomyocytes and skeletal myocytes exert either protective or pathologic effects on their neighboring cells through molecular cargo (Choi JS et al., 2016; Gartz M, and Strande JL, 2018). It is unclear whether cardiomyopathy develops as a primary or secondary consequence of skeletal muscle dysfunction in the muscular dystrophies. In DMD, where cardiomyopathy occurs in over half of all patients, it is still not known whether the severity of skeletal muscle disease influences the outcome of cardiomyopathy, and whether correcting the skeletal muscle deficiency benefits or harms the heart (Duan D, 2006; Shin JH et al., 2010). Whether the potential cardio-skeletal communication is mediated by exosomes released during the disease process is still a matter of investigation.

Several current treatments for muscle diseases selectively treat skeletal muscle while leaving the heart unprotected, although a few cardiac-specific treatments have been examined (Adamo CM et al., 2010; Afzal MZ et al., 2016; Ishikawa Y et al., 1999). Considering heart failure is often an inevitable consequence for patients with some types of muscular dystrophy, it would be important to identify whether exosomal communication between the cardiac and skeletal muscle is occurring. This knowledge could lead to better understanding of early molecular changes occurring in diseased cells, which in turn, may either perpetuate the disease process or upregulate pathways of protectin in nearby and distant cells. Furthermore, clarification of whether skeletal muscle therapies alter exosomal miRNA cargo, and whether altered cargo improves cardiac outcomes would further support the notion that skeletal myocytes can secrete signals that may protect the heart in neuromuscular diseases. Altering exosome communication between skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle may be an appealing approach to prevent the development and progression of heart failure in patients with neuromuscular diseases.

III. Conclusions

Numerous studies have supported miRNAs and exosomes to be key regulators and moderators of the muscle development, maintenance and disease processes. The molecular construction of miRNAs, as well as its affinity for molecular and intervesicular transport mechanisms, allow miRNAs the potential to be developed into circulating biomarkers for diagnostic and/or prognostic purposes. Furthermore, miRNA sorting and exosome cargo loading are altered between physiological and pathological conditions, which allow exosomal associated miRNAs to play a more active role in promoting the disease process by affecting the phenotype of the recipient cell. Exosomes also have functions outside their miRNA cargo. They have been shown to transfer proteins to recipient cells as well as trigger signaling pathways to alter cellular phenotypes. Understanding these processes further will be important for developing miRNA and/or associated exosomes into specific therapies. For instance, modulating exosomal surface proteins to gain selective homing to specific cell types will allow for targeted therapies after systemic injection. Engineering exosomes to preferentially express specific miRNAs may also improve the function of the recipient cells. Inhibiting the secretion of disease or harmful exosomes is also a possibility as therapeutic strategy although it is not well defined. Further understanding of pathways involved in exosome biology, factors that affect loading of cargo such as miRNA, as well as mechanisms of organ crosstalk in both normal and pathological conditions will potentially lead to a better understanding of the impact of exosomes and specific miRNAs on muscle diseases and may lead to novel treatment approaches. A successful implementation of these insights into translational studies and clinical trials represents the next step, as well as a promising approach to the complement existing therapeutic options for the treatment of muscle injury and disease processes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutions of Health Grant Number R01HL134932 to J.L.S. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

REFERENCES

- Abels ER, Breakefield XO. (2016). Introduction to Extracellular Vesicles: Biogenesis, RNA Cargo Selection, Content, Release, and Uptake. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 36(3), 301–312. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0366-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo CM, Dai DF, Percival JM, Minami E, Willis MS, Patrucco E, Froehner SC, Beavo JA. (2010). Sildenafil reverses cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(44), 19079–19083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013077107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzal MZ, Reiter M, Gastonguay C, McGivern JV, Guan X, Ge ZD, Mack DL, Childers MK, Ebert AD, Strande JL. (2016). Nicorandil, a Nitric Oxide Donor and ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channel Opener, Protects Against Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther, 21(6), 549–562. doi: 10.1177/1074248416636477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadi S, Wang X, Gu H, Fan GC. (2015). Pathologic function and therapeutic potential of exosomes in cardiovascular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1852(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MS, Casar JC, Motohashi N, Vieira NM, Eisenberg I, Marshall JL, Gasperini MJ, Lek A, Myers JA, Estrella EA, Kang PB, Shapiro F, Rahimov F, Kawahara G, Widrick JJ, Kunkel LM. (2014). MicroRNA-486-dependent modulation of DOCK3/PTEN/AKT signaling pathways improves muscular dystrophy-associated symptoms. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 6(124), 2651–2667. doi: 10.1172/JCI73579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose KK, Ishak T, Lian LH, Goh KJ, Wong KT, Ahmad-Annuar A, Thong MK. (2017). Deregulation of microRNAs in blood and skeletal muscles of myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients. Neurology India, 3(65), 512–517. doi: 10.4103/neuroindia.NI_237_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminzadeh MA, Rogers RG, Fournier M, Tobin RE, Guan X, Childers MK, Andres AM, Taylor DJ, Ibrahim A, Ding X, Torrente A, Goldhaber JM, Lewis M, Gottlieb RA, Victor RA, Marban E. (2018). Exosome-Mediated Benefits of Cell Therapy in Mouse and Human Models of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Stem Cell Reports, 10(3), 942–955. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoasii L, Hildyard JCW, Li H, Sanchez-Ortiz E, Mireault A, Caballero D, Harron R, Stathopoulou TR, Massey C, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, Piercy RJ, Olson EN. (2018). Gene editing restores dystrophin expression in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science, 6410(362), 86–91. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoi W, Sakuma K. (2014). Does regulation of skeletal muscle function involve circulating microRNAs? Front Physiol, 5, 39. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan F, Lai RC, Smeets MB, Akeroyd L, Choo A, Aguor EN, Timmers L, van Rijen HV, Doevendans PA, Pasterkamp G, Lim SK, de Kleijn DP. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes increase ATP levels, decrease oxidative stress and activate PI3K/Akt pathway to enhance myocardial viability and prevent adverse remodeling after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res, 10(3), 301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham R, Sas-Chen A, Manor O, Steinfeld I, Shalgi R, Tarcic G, Bossel N, Zeisel A, Amit I, Zwang Y, Enerly E, Russnes HG, Biagioni F, Mottolese M, Strano S, Blandino G, Børresen-Dale AL, Pilpel Y, Yakhini Z, Segal E, Yarden Y. (2010). EGF decreases the abundance of microRNAs that restrain oncogenic transcription factors. Science Signaling, 124(3), ra43. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bail S, Swerdel M, Liu H, Jiao X, Goff LA, Hart RP, Kiledjian M. (2010). Differential regulation of microRNA stability. RNA, 5(16), 1032–1039. doi: 10.1261/ma.1851510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang C, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Gupta SK, Foinquinos A, Holzmann A, Just A, Remke J, Zimmer K, Zeug A, Ponimaskin E, Schmiedl A, Yin X, Mayr M, Halder R, Fischer A, Engelhardt S, Wei Y, Schober A, Fiedler J, Thum T. (2014). Cardiac fibroblast-derived microRNA passenger strand-enriched exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest, 124(5), 2136–2146. doi: 10.1172/jci70577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile L, Cervio E, Lionetti V, Milano G, Ciullo A, Biemmi V, Bolis S, Altomare C, Matteucci M, Di Silvestre D, Brambilla F, Fertig TE, Torre T, Demertzis S, Mauri P, Moccetti T, Vassalli G. (2018). Cardioprotection by cardiac progenitor cell-secreted exosomes: role of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Cardiovasc Res, 114(7), 992–1005. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile L, Lionetti V, Cervio E, Matteucci M, Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM, Torre T, Siclari F, Moccetti T, Vassalli G. (2014). Extracellular vesicles from human cardiac progenitor cells inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res, 105(4), 530–541. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei Y, Xu T, Lv D, Yu P, Xu J, Che L, Das A, Tigges J, Toxavidis V, Ghiran I, Shah R, Li Y, Zhang Y, Das S, Xiao J. (2017). Exercise-induced circulating extracellular vesicles protect against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol, 112(4), 38. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0628-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ. (2005). MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semininars in Cell and Developmental Biology, 4–5(16), 585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beynon RP, Ray SG. (2008). Cardiac involvement in muscular dystrophies. Qjm, 101(5), 337–344. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittel DC, Jaiswal JK. (2019). Contribution of Extracellular Vesicles in Rebuilding Injured Muscles. Frontiers in Physiology, 10(828). doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. (2011). Exosome Secretion: Molecular Mechanisms and Roles in Immune Responses. Traffic, 12(12), 1659–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehler JF, Hogarth MW, Barberio MD, Novak JS, Ghimbovschi S, Brown KJ, Alemo Munters L, Loell I, Chen YW, Gordish-Dressman H, Alexanderson H, Lundberg IE, Nagaraju K. (2017). Effect of endurance exercise on microRNAs in myositis skeletal muscle - A randomized controlled study. PLoS One, 8(12), e0183292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, Martone J, Cazzella V, D’Amico A, Bertini E, Bozzoni I. (2011). miRNAs as serum biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 5(5). doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacchiarelli D, Martone J, Girardi E, Cesana M, Incitti T, Morlando M, Nicoletti C, Santini T, Sthandier O, Barberi L, Auricchio A, Musarò A, Bozzoni I. (2010). MicroRNAs involved in molecular circuitries relevant for the Duchenne muscular dystrophy pathogenesis are controlled by the dystrophin/nNOS pathway. Cell Metab, 12(4), 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan DM, Toth MJ. (2013). Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in human heart failure. Curr Opin Clin NutrMetab Care, 16(1), 66–71. doi: 10.1097/MC0.0b013e32835a8842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfrán-Duque A, Lin CS, Goedeke L, Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C. (2016). microRNAs and HDL Metabolism. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 56(6), 1076–1084. doi:doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caponnetto F, Manini I, Skrap M, Palmai-Pallag T, Di Loreto C, Beltrami AP, Cesselli D, Ferrari E. (2017). Size-dependent cellular uptake of exosomes. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 13(3), 1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. (2006). The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nature Genetics, 2(38), 228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhang L, Shen C, Qin G, Ashraf M, Weintraub N, Ma G, Tang Y. (2013). Cardiac progenitor-derived exosomes protect ischemic myocardium from acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 431(3), 566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PS, Su JL, Cha ST, Tarn WY, Wang MY, Hsu HC, Lin MT, Chu CY, Hua KT, Chen CN, Kuo TC, Chang KJ, Hsiao M, Chang YW, Chen JS, Yang PC, Kuo ML. (2011). miR-107 promotes tumor progression by targeting the let-7 microRNA in mice and humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 9(121), 3442–3455. doi: 10.1172/JCI45390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Huang Z, Chen D, Yang T, Liu G. (2013). MicroRNA-27a is induced by leucine and contributes to leucine-induced proliferation promotion in C2C12 cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 7(14), 14076–14084. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Gelfond J, McManus LM, Shireman PK. (2011). Temporal microRNA expression during in vitro myogenic progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation: regulation of proliferation by miR-682. Physiological Genomics, 10(43), 621–630. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00136.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Melton DW, Gelfond JA, McManus LM, Shireman PK. (2012). MiR-351 transiently increases during muscle regeneration and promotes progenitor cell proliferation and survival upon differentiation. Physiological Genomics, 21(44). doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00052.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Yoon HI, Lee KS, Choi YC, Yang SH, Kim IS, Cho YW. (2016). Exosomes from differentiating human skeletal muscle cells trigger myogenesis of stem cells and provide biochemical cues for skeletal muscle regeneration. Journal of Controlled Release, 222, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A, Turkes A, Dewitt S, Steadman R, Mason MD, Hallett MB. (2004). Adhesion and signaling by B cell-derived exosomes: the role of integrins. The FASEB Journal, 18. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1094fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo M, Moita C, van Niel G, Kowal J, Vigneron J, Benaroch P, Manel N, Moita LF, Théry C, Raposo G. (2013). Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. Journal of Cell Science, 126. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist CG, Montarras D, Pallafacchina G, Rocancourt D, Cumano A, Conway SJ, Buckingham M. (2009). Muscle stem cell behavior is modified by microRNA-27 regulation of Pax3 expression. PNAS, 32(106), 13383–13387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900210106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gasperi R, Hamidi S, Harlow LM, Ksiezak-Reding H, Bauman WA, Cardozo CP. (2017). Denervation-related alterations and biological activity of miRNAs contained in exosomes released by skeletal muscle fibers. Scientific Reports. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13105-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonbreun AR, McNally EM. (2017). Muscle cell communication in development and repair. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 34, 7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Chen JF, Wang DZ. (2011). Transgenic overexpression of miR-133a in skeletal muscle. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 26(12), 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzer K, Kleijmeer MJ, Heijnen HFG, Stoorvogel W, Geuze HJ. (2000). Exosome: from internal vesicle of the multivesicular body to intercellular signaling device. Journal of Cell Science, 113, 3365–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey BK, Gagan J, Dutta A. (2011). miR-206 and −486 induce myoblast differentiation by downregulating Pax7. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 7(31), 203–214. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01009-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz GP, Wang DZ. (2016). Regulation of Skeletal Muscle by microRNAs. Comprehensive Physiology, 3(6), 1279–1294. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev P, Stankevicins L, Ansseau E, Petrov A, Barat A, Dessen P, Robert T, Turki A, Lazar V, Labourer E, Belayew A, Carnac G, Laoudj-Chenivesse D, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS. (2013). Defective regulation of microRNA target genes in myoblasts from facioscapulohumeral dystrophy patients. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 49(288), 34989–35002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Gao X, Dai Y, Ran N, Yin H. (2018). Serum exosomes can restore cellular function in vitro and be used for diagnosis in dysferlinopathy. Theranostics, 8(5), 1243–1255. doi: 10.7150/thno.22856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza RF, Woodhead JST, Zeng N, Blenkiron C, Merry TL, Cameron-Smith D Mitchell CJ. (2018). Circulatory exosomal miRNA following intense exercise is unrelated to muscle and plasma miRNA abundances. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism, E723–E733. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00138.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D (2006). Challenges and opportunities in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet, 15 Spec No 2, R253–261. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg I, Eran A, Nishino I, Moggio M, Lamperti C, Amato AA, Lidov HG, Kang PB, North KN, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S, Flanigan KM, Neely LA, Whitney D, Beggs AH, Kohane IS, Kunkel LM. (2007). Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression in primary muscular disorders. PNAS, 43(104), 17016–17021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708115104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Xing W, Xie L. (2016). Regulatory Roles of MicroRNAs in Diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 10(17). doi: 10.3390/ijms17101729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo AA, Heier CR, Novak JS, Tully CB, Brown KJ, Uaesoontrachoon K, Vila MC, Ngheim PP, Bello L, Kornegay JN, Angelini C, Partridge TA, Nagaraju K, Hoffman EP. (2015). TNF-α-Induced microRNAs Control Dystrophin Expression in Becker Muscular Dystrophy. Cell Reports, 10(12), 1678–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forterre A, Jalabert A, Berger E, Baudet M, Chikh K, Errazuriz E, De Larichaudy J, Chanon S, Weiss-Gayet M, Hesse AM, Record M, Geloen A, Lefai E, Vidal H, Coute Y, Rome S. (2014). Proteomic analysis of C2C12 myoblast and myotube exosome-like vesicles: a new paradigm for myoblast-myotube cross talk? PLoS One, 9(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattini P, Villa C, De Santis F, Meregalli M, Belicchi M, Erratico S, Bella P, Raimondi MT, Lu Q, Torrente Y. (2017). Autologous intramuscular transplantation of engineered satellite cells induces exosome-mediated systemic expression of Fukutin-related protein and rescues disease phenotype in a murine model of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2I. Hum Mol Genet, 26(19), 3682–3698. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhbeis C, Helmig S, Tug S, Simon P, Kramer-Albers EM. (2015). Physical exercise induces rapid release of small extracellular vesicles into the circulation. J Extracell Vesicles, 4, 28239. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.28239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Yoshioka Y, Ito S, Araya J, Kuwano K, Ochiya T. (2014). Intercellular communication by extracellular vesicles and their microRNAs in asthma. Clinical Therapeutics, 36(6). doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimov A, Merry TL, Luca E, Rushing EJ, Mizbani A, Turcekova K, Hartung A, Croce CM, Ristow M, Krützfeldt J. (2016). MicroRNA-29a in Adult Muscle Stem Cells Controls Skeletal Muscle Regeneration During Injury and Exercise Downstream of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2. Stem Cells, 5(34), 768–780. doi: 10.1002/stem.2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambardella S, Rinaldi F, Lepore SM, Viola A, Loro E, Angelini C, Vergani L, Novelli G, Botta A. (2010). Overexpression of microRNA-206 in the skeletal muscle from myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients. Journal of Translational Medicine, 8(20). doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangoda L, Boukouris S, Liem M, Kalra H, Mathivanan S. (2015). Extracellular vesicles including exosomes are mediators of signal transduction: are they protective or pathogenic? Proteomics, 15(2–3), 260–271. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartz M, Darlington A, Afzal MZ, Strande JL. (2018). Exosomes exert cardioprotection in dystrophin- deficient cardiomyocytes via ERK1/2-p38/MAPK signaling. Sci Rep, 8(1), 16519. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34879-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartz M, Strande JL. (2018). Examining the Paracrine Effects of Exosomes in Cardiovascular Disease and Repair. J Am Heart Assoc, 7(11). doi: 10.1161/jaha.117.007954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgantas RW, Streicher K, Greenberg SA, Greenlees LM, Zhu W, Brohawn PZ, Higgs BW, Czapiga M, Morehouse CA, Amato A, Richman L, Jallal B, Yao Y, Ranade K. (2014). Inhibition of myogenic microRNAs 1, 133, and 206 by inflammatory cytokines links inflammation and muscle degeneration in adult inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 4(66), 1022–1033. doi: 10.1002/art.38292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goljanek-Whysall K, Pais H, Rathjen T, Sweetman D, Dalmay T, Munsterberg A. (2012). Regulation of multiple target genes by miR-1 and miR-206 is pivotal for C2C12 myoblast differentiation. J Cell Sci, 125 (Pt 15), 3590–3600. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goljanek-Whysall K, Sweetman D, Abu-Elmagd M, Chapnik E, Dalmay T, Hornstein E, Munsterberg A. (2011). MicroRNA regulation of the paired-box transcription factor Pax3 confers robustness to developmental timing of myogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 108(29), 11936–11941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105362108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco S, De Simone M, Colussi C, Zaccagnini G, Fasanaro P, Pescatori M, Cardani R, Perbellini R, Isaia E, Sale P, Meola G, Capogrossi MC, Gaetano C, Martelli F. (2009). Common micro-RNA signature in skeletal muscle damage and regeneration induced by Duchenne muscular dystrophy and acute ischemia. FASEB J., 10(23), 3335–3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco S, Perfetti A, Fasanaro P, Cardani R, Capogrossi MC, Meola G, Martelli F. (2012). Deregulated microRNAs in myotonic dystrophy type 2. PLoS One, 6(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harafuji N, Schneiderat P, Walter MC, Chen YW. (2013). miR-411 is up-regulated in FSHD myoblasts and suppresses myogenic factors. Orphanet J Rare Dis., 8(5). doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Zheng S, Luo Y, Wang B. (2018). Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics, 8(1), 237–255. doi: 10.7150/thno.21945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Hannon GJ. (2004). MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 5(7), 522–531. doi:doi: 10.1038/nrg1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Tréguer K, Boettger T, Horrevoets AJ, Zeiher AM, Scheffer MP, Frangakis AS, Yin X, Mayr M, Braun T, Urbich C, Boon RA, Dimmeler S (2012). Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nature Cell Biology(14), 249–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Ikeda K, Tsushima H, Fujishiro M, Hayakawa K, Yoshida Y, Morimoto S, Yamaji K, Takasaki Y, Takamori K, Tamura N, Sekigawa I. (2018). Circulating plasma microRNA profiling in patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis before and after treatment: miRNA may be associated with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Inflammation and Regeneration, 38(8). doi: 10.1186/s41232-017-0058-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Kong M, Ye Y, Hong S, Cheng L, Jiang L. (2014). Serum miR-206 and other muscle-specific microRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Neurochemistry, 5(129), 877–883. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YY, Lian YJ, Xu HL, Zheng YK, Li CF, Zhang JW, Yan SP. (2018). Novel, de novo dysferlin gene mutations in a patient with Miyoshi myopathy. Neuroscience Letters, 664, 107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Chen X, Yu B, He J, Chen D. (2012). MicroRNA-27a promotes myoblast proliferation by targeting myostatin. Biochem BiophysRes Commun, 2(432), 265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH. (2008). ESCRT complexes and the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 20(1), 4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y, Bach JR, Minami R. (1999). Cardioprotection for Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. Am Heart J, 137(5), 895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70414-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa H, Tomari Y. (2015). The Functions of MicroRNAs: mRNA Decay and Translational Repression. Trends in Cell Biology, 25(11), 651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H, Imamura T, Morino K, Shimosato T, Tawa M, Ugi S, Sakurai H, Maegawa H, Okamura T. (2015). MicroRNA-494 plays a role in fiber type-specific skeletal myogenesis in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 468(1–2), 208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Sucharov J, Stauffer BL, Miyamoto SD, Sucharov CC. (2017). Exosomes from pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy patients modulate a pathological response in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 312(4), H818–h826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00673.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan T, Fürthauer M. (2018). Biogenesis and function of ESCRT-dependent extracellular vesicles. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 74, 66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsotra A, Singh RK, Gurha P, Ward AJ, Creighton CJ, Cooper TA. (2014). The Mef2 transcription network is disrupted in myotonic dystrophy heart tissue, dramatically altering miRNA and mRNA expression. Cell Reports, 2(6), 336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoulidou A, Kyriakides TC, Papadimas GK, Christou Y, Kararizou E, Papanicolaou EZ, Phylactou LA. (2015). Elevated Muscle-Specific miRNAs in Serum of Myotonic Dystrophy Patients Relate to Muscle Disease Progress. PLoS One, 4(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J, Tkach M, Théry C. (2014). Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 29, 116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. (2010). The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nature Reviews. Genetics, 9(11), 597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. (2001). Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science, 5543(294), 853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC, Wiel C, Rubin GM. (2004). Complementary miRNA pairs suggest a regulatory role for miRNA:miRNA duplexes. RNA, 2(10), 171–175. doi: 10.1261/rna.5191904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. (2002). MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. The EMBO Journal, 21(17), 4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Li L, Ge M, Gu L, Wang M, Zhang K, Su Y, Zhang Y, Liu C, Lan M, Yu Y, Wang T, Li Q, Zhao Y, Yu Z, Li N, Meng Q. (2019). Overexpression of miR-29 Leads to Myopathy that Resemble Pathology of Ullrich Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Cells, 5(8), E459. doi: 10.3390/cells8050459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. (2008). microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes & Development, 23(22), 3242–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Williams AH, Maxeiner JM, Bezprozvannaya S, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. (2012). microRNA-206 promotes skeletal muscle regeneration and delays progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 6(122), 2054–2065. doi: 10.1172/JCI62656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Gao Y, Yang J, Shi C, Wang Y, Xu Y. (2018). MicroRNA-381 reduces inflammation and infiltration of macrophages in polymyositis via downregulating HMGB1. International Journal of Oncology, 3(53), 1332–1342. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz MA, Marques MJ, Santo Neto H. (2002). Impaired regeneration of dystrophin-deficient muscle fibers is caused by exhaustion of myogenic cells. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 6(35), 691–695. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2002000600009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho R, Alcantara PSM, Ottoch JP, Seelaender M. (2018). Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs and myomiRs in the Development of Cancer Cachexia-Associated Muscle Wasting. Frontiers in Nutrition, 4. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2017.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiyalagan P, Liang Y, Kim D, Misener S, Thorne T, Kamide CE, Klyachko E, Losordo DW, Hajjar RJ, Sahoo S. (2017). Angiogenic Mechanisms of Human CD34+ Stem Cell Exosomes in the Repair of Ischemic Hindlimb. Circulation Research, 120, 1466–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka Y, Kishi S, Aoki Y, Komaki H, Oya Y, Takeda S, Hashido K. (2014). Three novel serum biomarkers, miR-1, miR-133a, and miR-206 for Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, and Becker muscular dystrophy. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 6(19), 452–458. doi: 10.1007/s12199-014-0405-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka Y, Tanihata J, Komaki H, Ishiyama A, Oya Y, Ruegg U, Takeda SI, Hashido K. (2016). Characterization and Functional Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles and Muscle-Abundant miRNAs (miR-1, miR-133a, and miR-206) in C2C12 Myocytes and mdx Mice. PLoS One, 11(12), e0167811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JJ. (2008). MicroRNA-206: the skeletal muscle-specific myomiR. Biochim Biophys Acta, 11(1779), 682–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey KJ, Powell KL, Ashton AW, Morris JM, McCracken SA. (2015). Exosomes: Mechanisms of Uptake. Journal of Circulating Biomarkers, 4. doi: 10.5772/61186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell DL, Vickers KC. (2016). Lipoprotein carriers of microRNAs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1851(12), 2069–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S, Parkin R, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. (2008). Circulating miRNA as stable blood-based bio markers for cancer detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(30), 10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelbrunn M, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, González S, Sánchez-Cabo F, González MÁ, Bernad A, Sánchez-Madrid F. (2011). Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nature Communications, 2. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton SU, Joshi M, Savic T, Beggs AH, Agrawal PB. (2015). Skeletal muscle microRNA and messenger RNA profiling in cofilin-2 deficient mice reveals cell cycle dysregulation hindering muscle regeneration. PLoS One, 4(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR. (2014). Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 3(1). doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Matsuyama S, Nakasa T, Kamei N, Akimoto T, Higashi Y, Ochi M. (2015). Mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived exosomes accelerate skeletal muscle regeneration. FEBS Letters, 589, 1257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasa T, Ishikawa M, Shi M, Shibuya H, Adachi N, Ochi M. (2010). Acceleration of muscle regeneration by local injection of muscle-specific microRNAs in rat skeletal muscle injury model. J Cell Mol Med, 14(10), 2495–2505. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00898.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu LS, Simionescu N, Sanda GM, Carnuta MG, Stancu CS, Popescu AC, Popescu MR, Vlad A, Dimulescu DR, Simionescu M, Sima AV. (2015). MiR-486 and miR-92a Identified in Circulating HDL Discriminate between Stable and Vulnerable Coronary Artery Disease Patients. PloS ONE, 10(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M, Liu J, Yang Q, Seok HY, Hu X, Deng ZL, Wang DZ. (2016). MicroRNA-155 facilitates skeletal muscle regeneration by balancing pro-and anti-inflammatory macrophages. Cell Death & Disease, 6(7). doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Sato Y, Garner RT, Kargl C, Wang C, Kuang S, Gilpin CJ, Gavin TP. (2019). Skeletal muscle-derived exosomes regulate endothelial cell functions via reactive oxygen species-activated nuclear factor-kappaB signalling. Exp Physiol, 104(8), 1262–1273. doi: 10.1113/ep087396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. (2018). Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira GP Jr, Porto WF, Palu CC, Pereira LM, Petriz B, Almeida JA, Viana J, Filho NNA, Franco OL, Pereira RW. (2018). Effects of Acute Aerobic Exercise on Rats Serum Extracellular Vesicles Diameter, Concentration and Small RNAs Content. Front Physiol, 9, 532. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke JR, Georges SA, Seay HR, Tapscott SJ, McManus MT, Goldhamer DJ, Swanson MS, Harfe BD. (2007). Essential role for Dicer during skeletal muscle development. Developmental Biology, 2(311), 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Croce CM. (2016). The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduction And Targeted Therapy, 1, 15004. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbellini R, Greco S, Sarra-Ferraris G, Cardani R, Capogrossi MC, Meola G, Martelli F. (2011).Dysregulation and cellular mislocalization of specific miRNAs in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuromuscular Disorders, 2(21), 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.11.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portilho DM, Alves MR, Kratassiouk G, Roche S, Magdinier F, de Santana EC, Polesskaya A, Harel-Bellan A, Mouly V, Savino W, Butler-Browne G, Dumonceaux J. (2015). miRNA expression in control and FSHD fetal human muscle biopsies. PLoS One, 2(10), e0116853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall ME, Gustafsson MK, Emerson CP Jr. (2002). Myogenic regulatory factors and the specification of muscle progenitors in vertebrate embryos. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 18, 747–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme GJ, Glinka Y, Lichner Z, Yousef GM. (2016). Neuropilin-1 is a receptor for extracellular miRNA and AGO2/miRNA complexes and mediates the internalization of miRNA that modulate cell function. Oncotarget, 7(42), 68057–68071. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowits G, Gerijel-Taylor C, Day JM, Taylor DD, Kloecker GH. (2009). Exosomal MicroRNA: A Diagnostic Marker for Lung Cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer, 10(1), 42–46. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. (2006). Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. PNAS, 25(103), 8721–8726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SJ, Konieczny SF. (1989). Identification of MRF4: a new member of the muscle regulatory factor gene family. Genes & Development, 12B(3), 2050–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos R, Carneiro I, Arce VM, Devesa J. (2002). Myostatin is an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. American Journal of Physiology, Cell Physiology, 5(282), C993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissland OS, Hong SJ, Bartel DP. (2011). MicroRNA destabilization enables dynamic regulation of the miR-16 family in response to cell-cycle changes. Molecular Cell, 6(43), 993–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robriquet F, Babarit C, Larcher T, Dubreil L, Ledevin M, Goubin H, Rouger K, Guével L. (2016). Identification in GRMD dog muscle of critical miRNAs involved in pathophysiology and effects associated with MuStem cell transplantation. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17(11), 209. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1060-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose BA, Force T, Wang Y. (2010). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the heart: angels versus demons in a heart-breaking tale. Physiol Rev, 90(4), 1507–1546. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00054.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegger S, Großhans H. (2012). MicroRNA turnover: when, how, and why. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 10(37), 436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem KZ, Moschetta M, Sacco A, Imberti L, Rossi G, Ghobrial IM, Manier S, Roccaro AM. (2016). Exosomes in Tumor Angiogenesis In Domenico Ribatti(Ed.), Tumor Angiogenesis Assays (Vol. 1464, pp. 25–34). New York, NY: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]