Abstract

Barrett’s oesophagus (BE) has been associated with an increased risk of both colorectal adenomas and colorectal cancer. A recent investigation reported a high frequency of BE in patients with adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-associated polyposis (FAP). The aim of the present study is to evaluate the prevalence of BE in a large cohort of patients with MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) and APC-associated adenomatous polyposis. Patients with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or MAP were selected and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy reports, pathology reports of upper GI biopsies were reviewed to determine the prevalence of BE in these patients. Histologically confirmed BE was found in 7 (9.7%) of 72 patients with MAP. The mean age of diagnosis was 60.2 years (range 54.1–72.4 years). Two patients initially diagnosed with low grade dysplasia showed fast progression into high grade dysplasia and esophageal cancer, respectively. Only 4 (1.4%) of 365 patients with FAP were found to have pathologically confirmed BE. The prevalence of BE in patients with MAP is much higher than reported in the general population. We recommend that upper GI surveillance of patients with MAP should not only focus on the detection of gastric and duodenal adenomas but also on the presence of BE.

Keywords: Barrett’s esophagus, MUTYH-associated polyposis, Familial adenomatous polyposis, Esophageal adenocarcinoma

Introduction

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) in Western populations has substantially increased over the past several decades. The majority of EACs is thought to derive from a precursor lesion—Barrett esophagus (BE). BE is characterized by the presence of columnar epithelium that has replaced the normal squamous cell lining of the distal esophagus. EAC develops through multistep progression from metaplasia into low grade dysplasia, high grade dysplasia, early adenocarcinoma, and, finally, invasive cancer. This metaplastic change is driven by chronic inflammation due to gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is aggravated by abdominal obesity and smoking [1, 2]. In addition to environmental factors associated with BE and EAC, also genetic factors are thought to play a role [3, 4].

The prevalence of BE in asymptomatic patients varies between 0.5 and 1.8% and in patients with reflux symptoms, between 1.5 and 12.3% ([5–9], Table 1). It has been reported that BE and EAC are associated with a higher incidence of (sporadic) colorectal adenomatous polyps [10]. Also, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) caused by germline mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, has been associated with an increased risk of developing BE [11, 12]. It is not known whether adenomatous polyposis caused by bi-allelic germline mutations in the MUTYH gene (MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)) is also associated with BE [13]. The MUTYH gene plays an important role in base excision repair. Base excision repair is a cellular mechanism that repairs damaged DNA throughout the cell cycle. It is responsible primarily for removing small, non-helix-distorting base lesions from the genome [14]. EAC has been reported as part of the extracolonic tumor spectrum of MAP [15].

Table 1.

The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) reported in the general population (GP) and patients with and without gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms

| Study | Year | Country | Total number of patients | Prevalence of BE in GP (%) | Prevalence of BE in patients with GERD (%) | Prevalence of BE in patients without GERD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronkainen et al. | 2005 | Sweden | 1000 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Zagari et al. | 2008 | Italy | 1033 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Peng et al. | 2009 | China | 2580 | 1.0 | – | 0.5 |

| Lee et al. | 2010 | South Korea | 2048 | 1.0 | 12.3 | 0.5 |

| Zou et al. | 2011 | China | 1030 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

Surveillance of the upper gastrointestinal (GI)-tract is recommended for patients with MAP and FAP because of the increased risk of gastric and duodenal adenomas [16]. In the present study we assessed the prevalence of BE and EAC by reviewing the endoscopy reports in a large cohort of patients with FAP and MAP.

Methods

Initially, the database of the Department of Genetics at the University Medical Centre Utrecht was used to identify patients diagnosed with a polyposis syndrome between November 1987 and April 2015. Patients with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of FAP or MAP were eligible for this study if one or more upper GI endoscopy reports and/or pathology reports of upper GI biopsies were available.

To increase the number of FAP and MAP patients, we also used data from the Dutch Hereditary Cancer Registry. This national registry, established in 1985, collect medical and pathology reports and reports of upper and lower GI endoscopy of all registered patients with FAP and MAP.

All available original upper-GI endoscopy reports were reviewed. Data on the presence of BE, length of BE and, if available, the Prague criteria (endoscopic grading system for BE) were recorded. Also, the presence of a hiatal hernia and GERD (based on the Los Angeles, LA classification [17]) were obtained. Secondly, the pathology reports of all included patients were collected from the PALGA (Dutch acronym for “Pathologisch-Anatomisch Landelijk Geautomatiseerd Archief”) database to confirm the histological diagnosis of BE. The PALGA database is a national automated archive where all pathology reports of all performed biopsies in the Netherlands are registered. BE was defined as esophageal columnar epithelium in the presence of goblet cells [18]. The available section slides of the Barrett biopsies were reviewed by an expert GI pathologist (GJHO and MML).

Only patients from the Department of Clinical Genetics that have given their informed consent for their medical records to be reviewed were included. All patients registered at the Dutch Hereditary Cancer Registry have given written informed consent for registration and use of their anonymous data for research.

Descriptive statistical analysis was used. Frequencies are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous data are presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)], and in the case of non-normally distributed data as median (range). Last follow-up was calculated as death, diagnosis of BE or end of the study.

Results

Prevalence of BE in patients with MAP

A total of 94 patients with genetically proven MAP were selected. In 72 of the 94 MAP patients, the upper GI endoscopy reports and/or pathology reports of upper GI biopsies were available, including 28 females and 44 males. The mean age at last follow-up was 60.9 years (range 27.3–87.6, SD 11.4) and the mean length of follow-up (in 60 of 72 MAP patients where data was available) was 10.1 years (range 0–26.2). Patients characteristics and endoscopic findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of endoscopic findings in the esophagus in MAP and FAP-patients

| MAP patients (%) | FAP patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 72 | 356 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 28 (38.9) | 179 (50.3) |

| Male | 44 (61.1) | 177 (49.7) |

| Age at last follow-up (range) | 60.9 (27.3–87.6) | 48.9 (30.3–86.0) |

| Endoscopic findings esophagus | ||

| Histologically proven Barrett’s mucosa | 7 (9.7) | 4 (1.4%) |

| Esophagus adenocarcinoma | 1 (1.4) | 0 |

| Other findings | ||

| Gastro-esophageal reflux esophagitis | 18 (25) | NA |

| Hiatal hernia | 10 (14) | NA |

MAP MUTYH-associated polyposis, FAP APC-associated polyposis. NA not available

A total of nine patients had an endoscopical diagnosis of BE, and in seven out of the nine patients, BE was confirmed by histology (Table 3). Revision of the section slides by an expert pathologist was possible in six out of seven patients, and in all six patients the diagnoses of BE was confirmed. Thus, the prevalence of pathologically confirmed BE in the total cohort was 9.7% (7/72). The seven patients with BE included five males and two females. The mean age at diagnosis of BE was 60.2 years (range 54.1–72.4 years, SD 6.5). The characteristics of the seven patients with BE are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical, genetic and pathological characteristics of seven MAP patients with Barrett’s esophagus

| Patient | Sex | Age at diagnosis (years) | Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Initial PA report | Revision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 61 | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | c.638C>T p.(Pro213Leu) | No dysplasia | No dysplasia |

| 2 | M | 72 | c.1147delC, p.(Glu369Argfs*39) | c.1214C>T p.(Pro405Leu) | High grade dysplasia | High grade dysplasia |

| 3 | F | 54 | c.1187G>A p.(Gly396Asp) | c.1214C>T p.(Pro405Leu) | Low grade dysplasia | No dysplasia |

| 4 | M | 58 | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | Low grade dysplasia | Not available |

| 5 | M | 57 | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | c.1214C>T p.(Pro405Leu) | No dysplasia | Indefinite for dysplasia |

| 6 | M | 55 | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | c.933 + 3A >C splice site intron 10 | No dysplasia | Indefinite for dysplasia |

| 7 | M | 65 | c.536A>G p.(Tyr179Cys) | c.1187G>A p.(Gly396Asp) | No dysplasia | No dysplasia |

Information on previous endoscopies was available in six out of the seven patients with BE. In three patients, BE was diagnosed at the first upper-GI endoscopy. In the remaining three patients, the previous endoscopy, performed 1–4 years earlier, did not demonstrate evidence for BE.

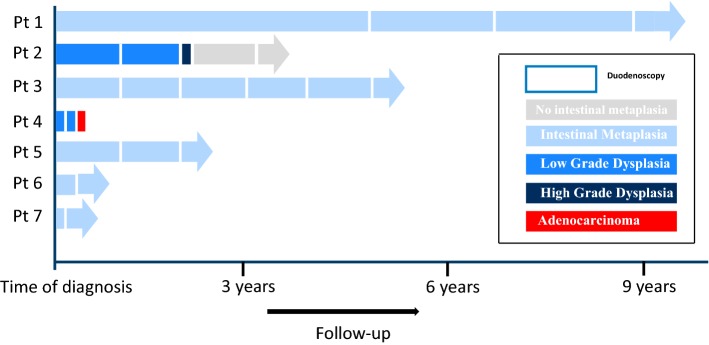

At time of diagnosis, two patients had low-grade dysplasia. The first patient developed high grade dysplasia after having low grade dysplasia in previous biopsies. The treatment consisted of piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection. The second patient, initially diagnosed with low grade dysplasia, developed adenocarcinoma after 6 months and underwent a surgical resection of a pT2N2Mx EAC. The follow-up of the patients with BE are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Findings at follow-up upper GI-endoscopies in the seven patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Arrow blocks represent screening intervals and the colors indicate the stage of metaplasia/dysplasia. pt patient. (Color figure online)

Prevalence of BE in patients with (A)FAP

In total, 407 FAP patients were identified from the 2 datasets. Upper GI endoscopy reports and/or pathology reports of upper GI biopsies were available in 356 patients including 177 males and 179 females. The mean age at the last follow-up was 48.9 years (range 30.3–86.0, SD 11.8).

In the total cohort, five patients with BE were detected. In four of these patients including two males and two females the diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination. In the fifth patient the diagnosis could not be confirmed as no goblet cells were present in the biopsies. The prevalence of histologically proven BE in this cohort is, therefore, 1.4%. The mean age at diagnosis of the four patients with BE was 52.5 years (range 34.0–60.0, SD 12.4). The endoscopic findings are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated a prevalence of BE (9.7%) in MAP patients which is > 5 times higher than reported in the general population. In contrast with a previous study, no increased frequency of BE was found in a large series of FAP-patients.

The prevalence of BE depends on which population is screened. In asymptomatic patients that undergo an upper GI endoscopy the prevalence varies between 0.5 and 1.8% and in patients with reflux symptoms, it is between 1.5 and 12.3% (Table 1; [5–9]). The proportion of MAP patients in our series with gastro-esophageal reflux esophagitis (25%) is not higher than reported in the general population which suggests that the frequency of BE is not increased by selection of symptomatic patients.

Another interesting finding was that in this small cohort of BE patients, two of the seven patients with initial low-grade dysplasia showed fast progression to high grade dysplasia and EAC, respectively. From a biological point of view our findings seem plausible. Persistent inflammation in esophageal mucosa due to acids and bile acids is associated with DNA impairment caused by increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [19–21]. One of the main defensive mechanisms to eliminate ROS induced DNA damage in cells is base-excision repair. Since MUTYH protein is a key player in base-excision repair, loss of the MUTYH-proteins could lead to accumulation of mutations and finally drive oncogenesis.

Analysis of our cohort of 356 FAP patients revealed that the prevalence of BE (1.4%) is not higher than in the general population. This is in contrast with a previous report on 36 (A)FAP patients of whom 6 (16%) had histologically proven BE [11]. We do not have an explanation for the observed differences but in view of the relatively small number of patients in the previous report, the findings might be due to chance. The fact that EAC has only been reported as part of the tumor spectrum of MAP but not in FAP supports our findings.

The strength of this study is the large number of patients with MAP and FAP and the long follow-up time.

In addition, all pathology reports were cross linked with the National Database (PALGA) and all biopsies of patients with BE were reviewed by an expert pathologist. There are also some limitations. At first, it is a retrospective analysis which might have led to selection of patients with BE. Secondly, not all risk-factors for the development of BE could be collected, such as smoking, obesity, symptoms of GERD or alcohol use.

What is the clinical implication of our study? Based on our observations, we recommend that upper GI surveillance of patients with MAP should not only focus on the identification of gastric and duodenal adenomas but also on the presence of BE. In view of the observed acceleration of high-grade dysplasia and EAC development, more intensive follow-up might be considered in patients with BE. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the prevalence of BE with patients with MAP is much higher compared to the general population. This can be explained by the impaired MUTYH protein function that plays a role in the repair of DNA damage caused by oxidative stress such as GERD.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank Dr. C.M.J. Tops for MUTYH mutation analysis.

Author contributions

Study concept and design (JJB, PDS, MGEMA); acquisition of data (CGD, MEV, ZG, JJB, GJAO, MML, MGEMA); analysis and interpretation of data (JJB, MGEMA, HFAV); drafting of the manuscript (CGD, MGEMA, JJB, HFAV, ZG); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (HFAV, PDS, GJAO, JJB).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ceranza G. Daans and Zeinab Ghorbanoghli are first authors.

References

- 1.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1375–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison RF, Perry I, Balkwill F, et al. Barrett’s metaplasia. Lancet. 2000;356:2079–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine DM, Ek WE, Zhang R, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1487–1493. doi: 10.1038/ng.2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ek WE, Levine DM, D’Amato M, et al. Germline genetic contributions to risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, and gastroesophageal reflux. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1711–1718. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander MA, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus in the general population: the Loiano-Monghidoro study. Gut. 2008;57:1354–1359. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng S, Cui Y, Xiao YL, et al. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in the adult Chinese population. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1011–1017. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee IS, Choi SC, Shim KN, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus remains low in the Korean population: nationwide cross-sectional prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1932–1939. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou D, He J, Ma X, et al. Epidemiology of symptom-defined gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis: the systematic investigation of gastrointestinal diseases in China (SILC) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:133–141. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.521888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumaravel A, Thota PN, Lee HJ, et al. Higher prevalence of colon polyps in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a case–control study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2014;2:281–287. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatalica Z, Chen M, Snyder C. Barrett’s esophagus in the patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta M, Dhavaleshwar D, Gupta V, et al. Barrett esophagus with progression to adenocarcinoma in multiple family members with attenuated familial polyposis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2011;7:340–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Tassan N, Chmiel NH, Maynard J, et al. Inherited variants of MYH associated with somatic G: C → T: A mutations in colorectal tumors. Nat Genet. 2002;30:227–232. doi: 10.1038/ng828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggieri V, Pin E, Russo MT, et al. Loss of MUTYH function in human cells leads to accumulation of oxidative damage and genetic instability. Oncogene. 2013;32:4500–4508. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogt S, Jones N, Christian D, et al. Expanded extracolonic tumor spectrum in MUTYH-associated polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1976–1985. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallagher M, Phillips R, Bulow S. Surveillance and management of upper gastrointestinal disease in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:263–273. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-5668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–328. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang KK, Sampliner RE, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olyaee M, Sontag S, Salman W, et al. Mucosal reactive oxygen species production in oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 1995;37:168–173. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez P, Piazuelo E, Sanchez MT, et al. Free radicals and antioxidant systems in reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2697–2703. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardikar S, Onstad L, Song X, et al. Inflammation and oxidative stress markers and esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence in a Barrett’s esophagus cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23:2393–2403. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]