Abstract

Introduction

The secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) family provides a seemingly endless array of potential biological functions that is only beginning to be appreciated. In humans, this family comprises 9 different members that vary in their tissue distribution, hydrolytic activity, and phospholipid substrate specificity. Through their lipase activity, these enzymes trigger various cell-signaling events to regulate cellular functions, directly kill bacteria, or modulate inflammatory responses. In addition, some sPLA2’s are high affinity ligands for cellular receptors.

Objective

This review merely scratches the surface of some of the actions of sPLA2s in innate immunity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. The goal is to provide an overview of recent findings involving sPLA2s and to point to potential pathophysiologic mechanisms that may become targets for therapy.

Key words: Atherosclerosis, Inflammation, Innate immunity, Lipoprotein, Eicosanoid

Introduction

The phospholipase A2 (PLA2, EC 3.1.1.4) family of enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of the sn-2 ester of glycerophospholipids to produce free fatty acids and lyso-phospholipids. Based on their primary actions, PLA2s are divided into cytosolic and secretory forms [1]. In addition, PLA2s are also subdivided into Ca2+-dependent and independent based on their requirement for Ca2+ for catalytic activity [2]. This review will specifically focus on the secretory members of the PLA2 (sPLA2) family with an emphasis placed on their respective biologic functions, in particular, their role in host immunity, inflammation and atherosclerosis. Other proposed roles for sPLA2s, including cell migration [3], apoptosis [4–6], reactive oxygen species generation and cytotoxicity [5, 7], proliferation and differentiation [8, 9], coagulation [10] and cancer [11, 12] are beyond the scope of this review.

Ten members of the sPLA2 family have been identified in mammals, which are numbered and grouped in order of their discovery: group IB (GIB), IIA, IIC, IID, IIE, IIF, III, V, X and XII (Table 1) [13]. The exact molecular structure, classification, genome localization and mechanisms of catalytic activity are reviewed in detail elsewhere [14–17]. The human genome encodes nine sPLA2’s, with group IIC existing as a pseudogene [18]. All sPLA2s contain a histidine/arginine catalytic dyad forming the active center and a conserved Ca2+-binding loop that is essential for the enzymes’ proper function. Although not closely related at the amino acid level (20–50% identity), the sPLA2’s share a common molecular weight (14–16 kDa) and are rich in disulfide bonds. The mammalian sPLA2’s have been subdivided into three structural classes, based on the position of disulfide bonds and sequence alignment [19]. Groups I, II, V and X sPLA2 comprise one subclass, and as such have similar primary structures and partially overlapping sets of disulfides. The ~55 kDa mammalian GIII sPLA2 is an atypical member of the sPLA2 family, containing a central domain that is similar to the classical GIII bee venom sPLA2 flanked by a 130-amino acid N-terminal domain and a 219-amino acid C-terminal domain [20]. Finally, GXIIA sPLA2 comprises the third subclass that is characterized by an unusual Ca2+ binding loop and position and spacing of cysteine residues [14, 21]. Group XIIB, a molecule homologous to GXIIA, has also been identified [22]. Group XIIB has a mutation in the catalytic site and has been shown to lack enzymatic activity.

Table 1.

Mammalian sPLA2s

| sPLA2 group | Tissue distributiona | Features and functions | Phospholipase activity | Binding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I B | Pancreatic secretions [23], lung [25], liver, spleen, kidney, and ovary [30], brain [31] | Digestion of dietary PLs [23], antibacterial [65], eicosanoid formation, cell contraction, proliferation [30], migration [11] | PG > PS >> PC [44] | M-type [40] | |

| II | A | Acute phase serum, intestinal mucosa, lacrimal gland cells, prostatic epithelial cells [36] | Acute phase protein [1,35], antibacterial [60–62, 64–66], cell proliferation [3, 4], migration [5], apoptosis [6], atherogenic [124] | PG > PS >> PC [44] | M-, N-type [40] HSPG [41] |

| C | Pseudogene (human) [18] Testis, pancreas (mouse) [44] | N/D | PG >> PC [44] | Low affinity to M-type [40] | |

| D | Pancreas, spleen, thymus, skin, lung, ovary, eosinophils [44] | N/D | low phospholipase activity PG~PC [44] | Low affinity to M-type [40] | |

| E | Thyroid gland, uterus, embryo [44] | Antibacterial [65] | PG > PC [44] | M-type [40] | |

| F | Placenta, testis, thymus, liver, kidney [44] | Antibacterial [65] | PG >> PC [44] | M-type [40] | |

| III | Kidney, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, placenta, leukocytes [20] | High molecular weight [20]. Antiviral [78] | PG > PC [44] | Low affinity to M-type [40] | |

| V | Heart, eye, pancreas [44], macrophages [99], neutrophils [69], mastocytes [70] | Antibacterial [17,65], antiviral [77], atherogenic [137,142], AA release, eicosanoid generation [51], phagocytosis [76] | PE > PC > PS [46] | HSPG [41] M-type [40] | |

| X | Intestine, lung, testis, stomach [44], neutrophils [69], macrophages [73] | Secreted as pro-enzyme [86]. Antibacterial [17, 65], antiviral [77], atherogenic [135], AA release, eicosanoid generation [52, 99] | PC > PS [45] | M-type [40] | |

| XII | A | Heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, pancreas [14] | Antibacterial [65] | Low phospholipase activity [14] PG > PS >> PC | Low affinity to M-type [40] |

| B | Liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, heart [22] | N/D | Inactive [22] | No binding to M-type [40] | |

aGIB and GIIA data are obtained from humans. GV and GX data are obtained from humans and mice. Data for the other sPLA2s are obtained from mice.

N/D not determined, PG phosphatidylglycerol, PS phosphatidylserine, PC phosphatidylcholline, HSPG heparan sulphate proteoglycans

The diversity in structure, enzymatic properties, and tissue distribution of sPLA2’s argue for a wide variety of physiological functions. The observation that one cell type can express more than one sPLA2 also implies that their biologic functions are not redundant. Historically, the first sPLA2, GIB sPLA2 (also known as pancreatic sPLA2) was identified in pancreatic secretions and recognized for its role in the digestion of dietary phospholipids [23–25]. Interestingly, mice deficient in GIB sPLA2 exhibit no defects in intestinal phospholipid digestion when fed a normal rodent diet, suggesting that other enzymes, such as pancreatic carboxyl ester lipase [26] and intestinal brush border phospholipase B [27] may compensate for the absence of GIB sPLA2. However, subsequent studies revealed that GIB sPLA2-deficient mice are resistant to high fat diet-induced obesity and obesity-related insulin resistance, suggesting this enzyme may play a critical role in dietary lipid absorption in the setting of a high fat diet [28]. The protection against insulin resistance was later attributed to reduced absorption of lysophospholipids, in particular, lyso-phosphatidylcholine (lyso-PC), in the GIB sPLA2-deficient mice [29]. These studies leave open the question whether inhibitors of pancreatic PLA2 would be of benefit in the context of high fat consumption in humans. GIB sPLA2 has also been detected in other tissues such as lung, liver, spleen, kidney, ovary and brain where additional functions have been proposed [11, 30, 31].

Subsequent to the identification of GIB sPLA2, GIIA sPLA2 (also known as non-pancreatic sPLA2) was isolated from the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis [32]. GIIA sPLA2, an acute phase reactant that is highly upregulated during inflammation, has been strongly associated with inflammatory conditions and its role in host defense has been established [32–36].

Defining the physiological functions of each of the members of the sPLA2 family poses a significant challenge. A common approach for studying their biologic functions has been to exogenously add purified recombinant sPLA2 to cells in vitro, or to over-express these enzymes in transfected cells. Gene-directed mRNA suppression and pharmacological suppression of sPLA2 activity in vitro has also been employed. However, with few exceptions, direct in vivo data to support in vitro findings have been lacking. To date, only a few animal models with altered expression of sPLA2 have been created, and findings from these in vivo models have not always been predicted by in vitro studies.

Recently, new functions have been attributed to sPLA2s that do not require enzymatic activity. Among these is the binding to and possible cell signaling through cell surface molecules [37–39]. For example, the relative binding affinity of the full set of mouse sPLA2’s to the M-type receptor has been documented [40]. Other members of the sPLA2 family, such as GIIA and GV sPLA2, bind proteoglycans with high affinity due to their overall positive charge [41, 42]. These properties suggest that the biologic functions of sPLA2s may extend beyond their enzymatic activity and may at least in part explain the existence of sPLA2s with poor phospholipase activity.

Biochemical properties

As their name indicates, sPLA2s catalyze the hydrolysis of phospholipids at the sn-2 position, a reaction that generates both free fatty acid and lysophospholipid. Due to the amphipathic structure of phospholipids, under physiologic conditions they are either incorporated in membranes or are part of vesicles with various complexity, such as micelles, lipoproteins or cellular membranes, with their hydrophilic head-groups turned to the aqueous phase and hydrophobic tails embedded in the inner parts of the membranes or the vesicles. Therefore, sPLA2s must penetrate the interphase comprised of phospholipid head groups to exert their action. As such, an important prerequisite for the action of sPLA2s is the successful binding to the phospholipid surface, and this property determines some specificities of their enzymatic activity. Indeed, the “interfacial specificity” for each of the different sPLA2’s can vary by several orders of magnitude [43].

In vitro studies utilizing recombinant enzymes and artificial phospholipid substrates have provided substantial information about the biochemical properties of the different members of the sPLA2 family. For example, GIIA as well as GIB sPLA2 have been shown to act on anionic phospholipids such as phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) but are virtually inactive to phosphatidylcholine (PC) due to the lack of high affinity binding [44]. In contrast, GV and GX sPLA2 hydrolyze PC with much higher efficiency compared to other members of the sPLA2 family due to a high binding affinity [43, 45]. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is a strong correlation between the ability of sPLA2s to hydrolyze PC-containing artificial substrates and their ability to hydrolyze mammalian cells and lipoprotein particles, which contain primarily PC on the outer surface. Thus, GV and GX sPLA2 have been shown to be the most potent sPLA2s in mediating phospholipid hydrolysis when added exogenously to mammalian cells, HDL and LDL [43, 45, 46], and accordingly, these two members of the sPLA2 family have received much attention.

Tryptophan residues located on the interfacial binding surfaces near the N terminus appear to be critical for the penetration of sPLA2 into zwitterionic interfaces. Thus, the molecular basis for the extremely low activity of GIIA sPLA2 to hydrolyze PC-rich vesicles, mammalian cell membranes, and serum lipoproteins is the absence of tryptophan residues that are present in both GV and GX sPLA2 [47, 48]. The capacity of GIIA sPLA2 to discriminate between PC-rich mammalian membranes and PG-rich membranes may be critical for its role in innate immunity. During acute infection, circulating levels of GIIA sPLA2 can increase up to three orders of magnitude [33]. High affinity binding to bacterial membranes that are rich in PG allows for selective phospholipid hydrolysis by GIIA sPLA2, providing effective bacterial killing while protecting mammalian membranes during an acute phase response.

In contrast to cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2)-α (also designated GIVA PLA2), which has a marked specificity for arachidonic acid at the sn-2 position of its substrate phospholipids [49, 50], members of the sPLA2 family are generally thought not to be arachidonyl-selective. Nevertheless, GV and GX sPLA2 have been shown to be quite potent in mobilizing arachidonic acid and stimulating eicosanoid synthesis in various cell types [51, 52], and thus may play an important role in inflammation and inflammatory diseases, as discussed in more detail in a subsequent section of this review. Interestingly, membrane sphingomyelin/ceramide content has been shown to modulate both the activity and arachidonic acid selectivity of GV and GX sPLA2 [46, 53–55], suggesting a novel mechanism whereby sphingolipids may regulate sPLA2-induced inflammatory responses. The exact mechanism by which sphingomyelin/ceramide modulates sPLA2 activity is not clearly understood, although the change in fatty acid specificity has been attributed to segregation of PC and sPLA2 between disordered and ordered sphingomyelin/free cholesterol/PC lipid phases [53].

Conditions associated with cellular injury including apoptosis have been shown to increase the susceptibility of cellular membranes to hydrolysis by GIIA sPLA2 (reviewed in [56]). This may relate to the increased exposure of PS on the outer leaflet of the membrane [57]. Oxidative modification of phospholipids also alters the physiochemical state of the membrane, which in turn affects the susceptibility of oxygenated and non-oxygenated fatty acid residues toward sPLA2 [58]. Perhaps relevant to atherosclerotic processes, the ability of GIIA sPLA2 to hydrolyze low density lipoproteins in vitro has been shown to be enhanced by mild oxidation [59].

Host defense

The innate immunity is a highly conserved function of mammalian organisms that provides a rapid yet non-specific response to various invading agents. This targeted and complex reaction serves to contain an infection prior to the induction of the adaptive immune response and involves various cell types, such as neutrophils, macrophages and natural killer cells and non-cellular host defense molecules, which range from simple inorganic molecules, such as hypochloric acid and nitric oxide, to more complex proteins or lipids. Abundant evidence indicates that certain members of the mammalian sPLA2 family play important roles in host defense against microbial pathogens (recently reviewed in [36]).

GIIA sPLA2 is predominantly recognized as part of the innate immune system and appears to be a major antibacterial factor against Gram-positive bacteria in human acute phase serum [60–62]. A study of patients with sepsis showed that of the nine human sPLA2’s, only GIIA sPLA2 could be detected in serum by time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay [63]. GIB sPLA2 could also be detected in sera of patients suffering from acute pancreatitis, presumably derived from injured pancreatic acinar cells that normally store this enzyme in an inactive form in zymogen granules. During acute infection, activation of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway leads to the induction of pro-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6, which in turn induce the expression of GIIA sPLA2 in multiple tissues [35].

GIIA sPLA2 efficiently kills various microorganisms, such as S. aureus, E. coli, S. typhimurium and L. monocytogenes [64–66]. Mice with transgenic expression of human GIIA sPLA2 are resistant to infection by S. aureus, E. coli, and B. anthracis [60, 67]. To achieve bacterial killing, the enzyme needs to gain access to bacterial cell membrane phospholipids. GIIA sPLA2 is able to penetrate the peptidoglycan envelope of Gram-positive bacteria due to its highly positive charge [65]. In contrast, the cell membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, which is coated by lipopolysaccharide is resistant to sPLA2 hydrolysis. Therefore, GIIA sPLA2 is capable of hydrolyzing the phospholipid of the bacterial cell membrane only after the lipopolysaccharide layer is disrupted by the action of the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein or the membrane attack complex of complement [62, 68].

Several other sPLA2s in addition to GIIA have been shown to have antibacterial activity. In rank order, the potency of sPLA2s in killing Gram-positive bacteria in vitro is: GIIA > GX > GV > GXIIA > GIIE > GIB > GIIF [65]. Identifying the precise antimicrobial roles of the various sPLA2s in different inflammatory cell types await further study. Current evidence suggests that GV and GX sPLA2 are expressed by human neutrophils, whereas GIIA sPLA2 is not detected [69]. In mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells, GIIA sPLA2 is found associated with secretory granules, while GV sPLA2 is present on Golgi membranes, the nuclear envelope, and the plasma membrane [70]. Increased phospholipase activity was reported in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with respiratory distress syndrome [71] and bronchial asthma [72], which was tentatively ascribed to GIIA sPLA2. However, a subsequent immunohistochemistry study showed that GIID, GV, and GX sPLA2 but not GIIA sPLA2 is present in human lung macrophages [73].

In addition to direct killing, sPLA2s may have indirect antibacterial effects through the activation of inflammatory cells [39]. For example, GIIA sPLA2 stimulates neutrophils to produce superoxide and release bactericidal enzymes [74]. It also has been proposed that GIIA plays a role in the removal of extracellular cell debris through a non-enzymatic process that involves bridging of the GIIA sPLA2 protein between anionic phospholipid vesicles and heparan sulfate proteoglycans on macrophages [75]. In response to zymosan stimulation, GV sPLA2 is recruited to phagosomes of macrophages where it activates cPLA2-α and leukotriene synthase, suggesting that it may participate in the killing of ingested bacteria through the regulation of eicosanoid production and as a component of the phagocytic machinery [76].

Antiviral functions have also been attributed to GIII, GV and GX sPLA2 [77, 78]. These sPLA2s apparently block adenoviral infection of cells through different mechanisms. In the case of GV and GX sPLA2, the anti-viral action appears to be due to the conversion of PC to lyso-PC in the host cell membrane, which interferes with virus fusion [77]. Interestingly, the anti-adenovirus effect of GIII sPLA2 is reportedly dependent on the catalytically active central domain as well as its unique N-terminal domain [79]. Studies to investigate the antiviral efficacy of these and other sPLA2s in vivo are warranted.

Inflammation and eicosanoid generation

In addition to its antimicrobial activity, sPLA2s contribute to innate immunity through the generation of various biologically active molecules that modulate immune responses [39]. As noted above, GIIA sPLA2 activity in serum can increase by several orders of magnitude during an acute phase response. The induction of other sPLA2’s during inflammation is not well established, and it is possible that there are species-specific differences in their regulation. In humans, the genes for GIIC, IID, IIE, IIF, and V sPLA2 are clustered at the same chromosomal locus of chromosome 1 as GIIA (1p34–36) [80, 81], and it is been suggested that the transcription of these genes may be co-regulated. However, studies investigating the induction of GV sPLA2 during inflammation have been conflicting [42, 82–85]. GX sPLA2 transcription does not appear to be induced by inflammatory stimuli [85]. Interestingly, findings from transgenic GX sPLA2 mice are consisted with post-translational regulation of GX sPLA2, such that during inflammation this molecule may be converted from an inactive pro-peptide form to the mature, catalytically active enzyme [86].

The generation of arachidonic acid via sPLA2 hydrolysis has the potential to give rise to a wide variety of bioactive lipid mediators, including prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and lipoxins. These molecules can have potent and pleiotropic effects that modulate inflammatory responses [87]. sPLA2s may provide arachidonic acid for eicosanoid synthesis via multiple proposed mechanisms. Through the “external plasma membrane pathway”, sPLA2 acts directly on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane to release free fatty acids. As summarized in a previous section, this pathway is thought to be operative in the case of GV and GX sPLA2, which are known to potently hydrolyze PC on the surface of cells. Another possibility is the “heparan sulphate proteoglycan (HSPG)-shuttling pathway”, whereby heparin-binding sPLA2s may be internalized and trafficked to intracellular compartments to release arachidonic acid for eicosanoid production [88]. GIIA and GV sPLA2 bind negatively charged HSPGs by virtue of cationic domains in their C-terminal region. Alternatively, sPLA2s may function intracellularly prior to secretion [89].

Numerous in vitro studies document the ability of GV and GX sPLA2, and to a lesser extent GIIA, to generate arachidonic acid for eicosanoid production in inflammatory cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils and mast cells (for recent review, see [17]). In some cases, this activity has been shown to involve cross-talk with cytosolic GIV or GVIB sPLA2s [89–97]. With few exceptions, such studies have involved transfection-mediated overexpression or exogenous addition of sPLA2. Suppression of endogenous GV sPLA2 using anti-sense oligonucleotides has been shown to significantly reduce LPS-stimulated prostaglandin-E2 production in 388D1 mouse macrophage-like cells [51]. Furthermore, peritoneal macrophages isolated from mice deficient in GV sPLA2 exhibit impaired zymosan-stimulated eicosanoid production [98]. However, only modest changes in eicosanoid levels were detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of mice with transgenic over-expression of GV sPLA2, despite approximately sevenfold increased sPLA2 activity in their lungs compared to wild-type mice [86]. In the case of GX sPLA2, mice with gene-targeted deletion of this enzyme exhibited dramatically reduced allergen-induced eicosanoid production and airway inflammation in an in vivo model of asthma [99]. A more recent study showed that GX sPLA2 −/− mice had attenuated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury which was at least partly due to the suppression of neutrophil cytotoxic activities [100].

An important area of research concerns the involvement of sPLA2s in the pathology of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is characterized by alterations in pulmonary surfactant composition that lead to increased alveolar surface tension, alveolar collapse, and severe disturbance of pulmonary gas exchange. Several studies have reported increased sPLA2 activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with ARDS [101–103] or severe pneumonia [73], and that pharmacological inhibition of sPLA2 protects animals against experimental ARDS [104]. A role for GV sPLA2 in lung pathology is also suggested by recent studies in GV sPLA2 transgenic mice [86]. Unexpectedly, these mice died in the neonatal period because of respiratory failure that was attributed to marked reduction of the lung surfactant phospholipids, PC and PG. In contrast, GX sPLA2 transgenic neonates displayed minimal abnormality of the respiratory tract with normal alveolar architecture and surfactant composition. Although this finding appears to be inconsistent with in vitro data that GX sPLA2 is more potent in hydrolyzing surfactant phospholipids compared to GV sPLA2, the lack of a phenotype in GX sPLA2 transgenic mice may be due to the fact that GX sPLA2, unlike GV sPLA2, is originally expressed in an inactive form that requires removal of 11 amino acid residues at the N terminus for catalytic activity [52]. The authors showed that the bulk of GX sPLA2 in lungs of the transgenic mice was present in the precursor form. This conclusion was borne out by a more recent study, in which the mature form of GX sPLA2 was expressed in transgenic mice using the macrophage-specific CD68 promoter [105]. These mice died neonatally due to severe lung pathology that was characterized by severe interstitial pneumonia, increased eicosanoid levels, and enhanced hydrolysis of lung surfactant. Future studies of experimental ARDS in GV and GX sPLA2-deficient mice will provide definitive evidence whether or not these sPLA2s contribute to lung dysfunction either by promoting inflammation-induced surfactant damage and/or pathological eicosanoid generation.

In addition to ARDs, numerous studies provide ample evidence for sPLA2 involvement in other diverse inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis [106], central nervous system inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases [107, 108], inflammatory bowel diseases including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [109, 110], and endotoxin-induced septic shock [111]. While GIIA sPLA2 is the major enzyme found elevated in the systemic circulation of patients with various acute and chronic inflammatory diseases, other sPLA2s have also been reported to be elevated locally at sights of inflammation and cell injury.

Interestingly, many of the biological effects exerted by sPLA2s on inflammatory and other cells appear to be independent of their catalytic activity [39]. The recognition that sPLA2’s may act through binding cellular targets distinct from membrane phospholipids was first appreciated through studies of snake and insect venoms [112, 113]. The N-type receptors, which bind with high affinity several neurotoxic sPLA2s, are highly expressed in mammalian brain membranes but have not yet been isolated or cloned. The M-type receptor mediates myotoxic effects of sPLA2s and is probably the best characterized binding protein for sPLA2s [113, 114]. This receptor is a 180-kDa member of the C-type lectin family that is structurally similar to the macrophage mannose receptor. Based on studies in vitro, the M-type receptor has been proposed to mediate several biological effects of GIB, GIIA, and GX sPLA2, including eicosanoid release, cell proliferation, cell migration, and cytokine induction [40, 115, 116]. On the other hand, the M-type receptor is an endocytic receptor, and it has been suggested that it may function to internalize and inactivate sPLA2’s [117, 118]. Mice deficient in the M-type receptor are resistant to LPS-induced lethality, suggesting a role in inflammation [111]. The full complement of mouse sPLA2’s have been assessed for their ability to bind the mouse M-type receptor [40]: sPLA2 IB, IIA, IIE, IIF, and X bind with highest affinity (K 0.5 = 0.3–3 nM); sPLA2 IIC and V bind with lower affinity (K 0.5 = 30–75 nM) and the remaining sPLA2’s bind only weakly or not at all (K 0.5 > 100 nM).

Intriguingly, human GIIA sPLA2 has very low binding affinity to the M-type receptor [119], suggesting that different receptors may mediate the actions that are independent of the enzyme’s catalytic activity in humans. Indeed, very recently Saegusa et al., reported that human GIIA sPLA2 binds with very high affinity to integrins αVβ3 and α4β1 and induces proliferation of a monocytic cell line directly connecting the pro-inflammatory functions of GIIA sPLA2 and integrins [120].

Atherosclerosis

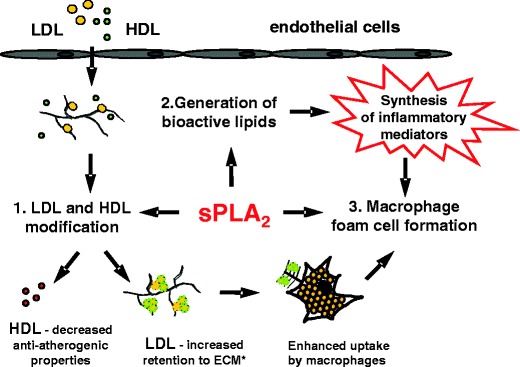

According to the “response to retention” hypothesis, a key event in atherosclerosis is the retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in the vessel wall, which initiates the recruitment of monocyte/macrophages [121, 122]. In an effort to remove excess lipid accumulated in the subendothelium, these cells may convert into “foam cells”. Simultaneously, inflammatory cytokines produced by various cell types present in the lesion trigger and sustain the inflammatory milieu [123, 124]. Lipid-laden cells and chronic inflammation eventually lead to core necrosis and plaque instability [125]. Current data suggest that sPLA2s may contribute to lipoprotein retention, foam cell formation, and inflammation in a developing lesion (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Model for atherogenic role of sPLA2. 1 Upon influx in the subendothelial space LDL and HDL are subject to hydrolysis by sPLA2 generating atherogenic LDL and HDL with decreased anti-atherogenic properties. 2 sPLA2 generates various bioactive lipids that promote inflammatory processes. 3 sPLA2 modified LDL is readily taken up by macrophages. ECM* extracellular matrix

A potential involvement of GIIA sPLA2 in atherosclerotic processes has been recognized for well over a decade [126]. This interest was further amplified with the 1999 finding that circulating levels of GIIA sPLA2 are an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events in humans [127]. The concurrent finding in 1999 that transgenic mice with constitutive expression of human GIIA sPLA2 spontaneously develop atherosclerosis even in the absence of hyperlipidemia provided compelling evidence that this enzyme contributes to atherogenic processes, and is not merely a marker for the disease [128]. GIIA sPLA2 transgenic animals exhibit systemic changes in lipoproteins including elevated VLDL/LDL cholesterol levels, lower HDL and decreased paraoxonase activity [128] that could contribute to increased atherosclerosis susceptibility. The decreased HDL was later shown to be due to an increase in the rate of hepatic selective uptake of HDL-cholesterol ester and plasma clearance of HDL [129, 130]. Subsequent studies in LDL receptor-deficient mice demonstrated that expression of human GIIA sPLA2 only in bone-marrow derived cells or specifically in macrophages increased lesion area without any detectable changes in systemic lipoproteins, indicating that sPLA2 in the local environment of a developing lesion is pro-atherogenic [131–133]. The recent discovery of additional members of the sPLA2 family that are present in lesions has raised the question of which sPLA2 subtypes contribute to atherosclerotic processes [134–136].

There are several potential mechanisms by which sPLA2s can affect atherosclerotic lesion development. As briefly reviewed in the previous section, sPLA2s may contribute to pro-inflammatory processes through the generation of bioactive lipid mediators, including free fatty acids and lysophospholipids. By liberating arachidonic acid, sPLA2 may promote the localized production of prostaglandins, leukotrienes and thromboxanes, all of which have potent pro-inflammatory and thrombogenic potential. A second mechanism by which sPLA2 may enhance lesion formation is through the generation of atherogenic lipoproteins [137–142]. Both GV and GX sPLA2 are capable of hydrolyzing LDL and HDL in vitro with higher potency compared to GIIA sPLA2, producing free fatty acids and lysophospholipids and structurally modified lipoprotein particles [45, 46, 137, 139]. LDL hydrolyzed by either GV or GX sPLA2 promotes macrophage foam cell formation in vitro [137, 139]. Our laboratory has investigated the molecular mechanism by which macrophages take up GV sPLA2-modified LDL, and have shown that this process is independent of scavenger receptors SR-A and CD36 and dependent on cell-surface proteoglycans [140]. This finding is in agreement with studies that sPLA2 modification of LDL leads to conformational changes in apoB that enhance apoB binding to proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix [143]. Interestingly, upon binding to proteoglycans, GV sPLA2 activity on LDL also increases [42]. Hydrolysis by sPLA2 may also impact lipid accumulation in the vessel wall by reducing the anti-atherogenic functions of HDL [141].

Consistent with the large body of in vitro data, a recent gain-of-function and loss-of-function study in LDL receptor-deficient mice confirmed that GV sPLA2 promotes atherosclerotic lipid deposition in vivo [144]. In the near future, valuable information about the role of GX sPLA2, and perhaps other members of the sPLA2 family known to be present in lesions [134], will be provided as appropriate mouse models become available. An important area of research that requires further investigation is the impact of sPLA2 on plaque stability. Several studies have reported that macrophage-specific overexpression of GIIA or GV sPLA2 leads to increased collagen content of atherosclerotic lesions in mice fed a high fat diet, compared to their wild type littermates [132, 133, 144]. Although not directly demonstrated, increased collagen deposition might be expected to provide a more stable plaque phenotype in lesions with enhanced expression of sPLA2. Clearly, more studies are needed to determine whether sPLA2 alters collagen deposition by enhancing its production or reducing its degradation in plaques, and whether such changes have an effect on plaque stability.

Summary and future directions

Elucidating the biologic functions of specific sPLA2s remains a significant challenge, given the relatively large number of family members, their overlapping tissue distribution, and their distinct biochemical properties. The development of specific reagents and animal models to probe their respective functions will undoubtedly lead to novel and important insights.

The inhibition of sPLA2 activity remains an attractive target in the treatment of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. However, the appropriate strategy should take into account their diversity, their potentially redundant activities and beneficial properties. Although sPLA2 inhibition has been achieved through the development of compounds that partition into the phospholipid membrane and decrease enzyme binding, such inhibitors exhibit low specificity and only modest efficacy [145]. In addition to the potentially adverse effects of the inhibitors per se, non-selective blockade of PLA2s may prove to be detrimental since they are involved in vital cell processes and have defensive functions that should not be overlooked. Since it appears that more than one sPLA2 may be involved in a particular process, selective targeting of only one sPLA2 may not be sufficient. An additional caveat is the recent recognition that in addition to acting as lipolytic enzymes, sPLA2s can serve as high affinity ligands for cell surface receptors. The fact that there are currently no available reagents that block enzymatic activity independent of receptor binding and vice versa is one complication in carrying out studies to elucidate the divergent functions of sPLA2s.

References

- 1.Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dennis EA. Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13057–13060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambero A, Landucci EC, Toyama MH, Marangoni S, Giglio JR, Nader HB, et al. Human neutrophil migration in vitro induced by secretory phospholipases A2: a role for cell surface glycosaminoglycans. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taketo MM, Sonoshita M. Phospolipase A2 and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:72–76. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giri S, Khan M, Rattan R, Singh I, Singh AK. Krabbe disease: psychosine-mediated activation of phospholipase A2 in oligodendrocyte cell death. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1478–1492. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600084-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao M, Brunk UT, Eaton JW. Delayed oxidant-induced cell death involves activation of phospholipase A2. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muralikrishna Adibhatla R, Hatcher JF. Phospholipase A2, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation in cerebral ischemia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda S, Yamamoto K, Hirabayashi T, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, Kudo I, et al. Human group III secreted phospholipase A2 promotes neuronal outgrowth and survival. Biochem J. 2008;409:429–438. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeno Y, Konno N, Cheon S, Bolchi A, Ottonello S, Kitamoto K, et al. Secretory phospholipases A2 induce neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells through lysophosphatidylcholine generation and activation of G2A Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28044–28052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mounier CM, Bon C, Kini RM. Anticoagulant venom and mammalian secreted phospholipases A 2: protein- versus phospholipid-dependent mechanism of action. Haemostasis. 2001;31:279–287. doi: 10.1159/000048074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorovetz M, Schwob O, Krimsky M, Yedgar S, Reich R. MMP production in human fibrosarcoma cells and their invasiveness are regulated by group IB secretory phospholipase A2 receptor-mediated activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1917–1925. doi: 10.2741/2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings BS. Phospholipase A2 as targets for anti-cancer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaloske RH, Dennis EA. The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim Biophysi Acta. 2006;176:1246–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelb MH, Valentin E, Ghomashchi F, Lazdunski M, Lambeau G. Cloning and recombinant expression of a structurally novel human secreted phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39823–39826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000671200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudo I, Murakami M. Phospholipase A2 enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:3–58. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winget JM, Pan YH, Bahnson BJ. The interfacial binding surface of phospholipase A2s. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;176:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Biochemistry and physiology of mammalian secreted phospholipases A2. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:495–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.062405.154007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tischfield JA, Xia YR, Shih DM, Klisak I, Chen J, Engle SJ, et al. Low-molecular-weight, calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 genes are linked and map to homologous chromosome regions in mouse and human. Genomics. 1996;32:328–333. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami M, Kudo I. Phospholipase A2. J Biochem. 2002;131:285–292. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentin E, Ghomashchi F, Gelb MH, Lazdunski M, Lambeau G. Novel human secreted phospholipase A2 with homology to the group III bee venom enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7492–7496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho IC, Arm JP, Bingham CO, III, Choi A, Austen KF, Glimcher LH. A novel group of phospholipase A2s preferentially expressed in type 2 helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18321–18326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouault M, Bollinger JG, Lazdunski M, Gelb MH, Lambeau G. Novel mammalian group XII secreted phospholipase A2 lacking enzymatic activity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11494–11503. doi: 10.1021/bi0349930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verheij HM, Slotboom AJ, de Haas GH. Structure and function of phospholipase A2. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;91:91–203. doi: 10.1007/3-540-10961-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puijk WC, Verheij HM, De Haas GH. The primary structure of phospholipase A2 from porcine pancreas a reinvestigation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;492:254–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seilhamer JJ, Randall TL, Yamanaka M, Johnson LK. Pancreatic phospholipase A2: isolation of the human gene and cDNAs from porcine pancreas and human lung. DNA. 1986;5:519–527. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1986.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richmond BL, Boileau AC, Zheng S, Huggins KW, Granholm NA, Tso P, et al. Compensatory phospholipid digestion is required for cholesterol absorption in pancreatic phospholipase A2-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1193–1202. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takemori H, Zolotaryov FN, Ting L, Urbain T, Komatsubara T, Hatano O, et al. Identification of functional domains of rat Intestinal phospholipase B/lipase its cDNA cloning, expression, and tissue distribution. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2222–2231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huggins KW, Boileau AC, Hui DY. Protection against diet-induced obesity and obesity- related insulin resistance in group 1B PLA2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E994–E1001. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00110.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labonte ED, Kirby RJ, Schildmeyer NM, Cannon AM, Huggins KW, Hui DY. Group 1B phospholipase A2-mediated lysophospholipid absorption directly contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2006;55:935–941. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanasaki K, Arita H. Phospholipase A2 receptor: a regulator of biological functions of secretory phospholipase A2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolko M, Christoffersen N, Varoqui H, Bazan N. Expression and Induction of secretory phospholipase A group IB in brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:1107–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-8221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seilhamer JJ, Pruzanski W, Vadas P, Plant S, Miller JA, Kloss J, et al. Cloning and recombinant expression of phospholipase A2 present in rheumatoid arthritic synovial fluid. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5335–5338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crowl RM, Stoller TJ, Conroy RR, Stoner CR. Induction of phospholipase A2 gene expression in human hepatoma cells by mediators of the acute phase response. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2647–2651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vadas P, Browning J, Edelson J, Pruzanski W. Extracellular phospholipase A2 expression and inflammation: the relationship with associated disease states. J Lipid Mediat. 1993;8:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevalainen TJ, Haapamäki MM, Grönroos JM. Roles of secretory phospholipases A2 in inflammatory diseases and trauma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevalainen TJ, Graham GG, Scott KF. Antibacterial actions of secreted phospholipases A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambeau G, Lazdunski E. Receptors for growing family of secreted phospholipase A2. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:162–170. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Granata F, Petraroli A, Boilard E, Bezzine S, Bollinger J, Del Vecchio L, et al. Activation of cytokine production by secreted phospholipase A2 in human lung macrophages expressing the M-type receptor. J Immunol. 2005;174:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triggiani M, Granata F, Frattini A, Marone G. Activation of human inflammatory cells by secreted phospholipases A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rouault M, LeCalvez C, Boilard E, Surrel F, Singer A, Ghomashchi F, et al. Recombinant production and properties of binding of the full set of mouse secreted phospholipases A2 to the mouse M-type receptor. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1647–1662. doi: 10.1021/bi062119b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sartipy P, Johansen B, Camejo G, Rosengren B, Bondjers G, Hurt-Camejo E. Binding of human phospholipase A2 type II to proteoglycans. Differential effect of glycosaminoglycans on enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26307–26314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosengren B, Peilot H, Umaerus M, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Mattsson-Hulten L, Hallberg C, et al. Secretory phospholipase A2 group V: lesion distribution, activation by arterial proteoglycans, and induction in aorta by a Western diet. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1579–1585. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000221231.56617.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer AG, Ghomashchi F, Le Calvez C, Bollinger J, Bezzine S, Rouault M, et al. Interfacial kinetic and binding properties of the complete set of human and mouse groups I, II, V, X, and XII secreted phospholipases A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48535–48549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valentin E, Ghomashchi F, Gelb M, Lazdunski M, Lambeau G. On the diversity of secreted phospholipases A2 cloning, tissue distribution, and functional expression of two novel mouse group II enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31195–31202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pruzanski W, Lambeau L, Lazdunsky M, Cho W, Kopilov J, Kuksis A differential hydrolysis of molecular species of lipoprotein phosphatidylcholine by groups IIA, V and X secretory phospholipases A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1736:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gesquiere L, Cho W, Subbaiah PV. Role of group IIa and group V secretory phospholipases A(2) in the metabolism of lipoproteins. Substrate specificities of the enzymes and the regulation of their activities by sphingomyelin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4911–4920. doi: 10.1021/bi015757x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beers SA, Buckland AG, Koduri RS, Cho W, Gelb MH, Wilton DC. The antibacterial properties of secreted phospholipases A2. A major physiological role for the group IIA enzyme that depends on the very high pI of the enzyme to allow penetration of the bacterial cell wall. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1788–1793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bezzine S, Bollinger JG, Singer AG, Veatch SL, Keller SL, Gelb MH. On the binding preference of human groups IIA and X phospholipases A2 for membranes with anionic phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48523–48534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murakami M, Kudo I, Umeda M, Matsuzawa A, Takeda M, Komada M, et al. Detection of three distinct phospholipases A2 in cultured mast cells. J Biochem. 1992;111:175–181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diez E, Louis-Flamberg P, Hall RH, Mayer RJ. Substrate specificities and properties of human phospholipases A2 in a mixed vesicle model. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18342–18348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balboa MA, Balsinde J, Winstead MV, Tischfield JA, Dennis EA. Novel group V phospholipase A2 involved in arachidonic acid mobilization in murine P388D1 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32381–32384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanasaki K, Ono T, Saiga A, Morioka Y, Ikeda M, Kawamoto K, et al. Purified group X secretory phospholipase A2 induced prominent release of arachidonic acid from human myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34203–34211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuksis A, Pruzanski W. Phase composition of lipoprotein sphingomyelin/cholesterol/PtdCho affects fatty acid specificity of sPLA2s. J Lipid Res. 2008;in press:M800167–JLR800200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Singh DK, Gesquiere LR, Subbaiah PV. Role of sphingomyelin and ceramide in the regulation of the activity and fatty acid specificity of group V secretory phospholipase A2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;459:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh DK, Subbaiah PV. Modulation of the activity and arachidonic acid selectivity of group X secretory phospholipase A2 by sphingolipids. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:683–692. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600421-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menschikowski M, Hagelgans A, Siegert G. Secretory phospholipase A2 of group IIA: is it an offensive or a defensive player during atherosclerosis and other inflammatory diseases? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;79:1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atsumi G, Murakami M, Tajima M, Shimbara S, Hara N, Kudo I. The perturbed membrane of cells undergoing apoptosis is susceptible to type II secretory phospholipase A2 to liberate arachidonic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1349:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nigam S, Schewe T. Phospholipase A2s and lipid peroxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eckey R, Menschikowski M, Lattke P, Jaross W. Minimal oxidation and storage of low density lipoproteins result in an increased susceptibility to phospholipid hydrolysis by phospholipase A2. Atherosclerosis. 1997;132:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laine VJ, Grass DS, Nevalainen TJ. Resistance of transgenic mice expressing human group II phospholipase A2 to Escherichia coli infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:87–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.1.87-92.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gronroos JO, Laine VJ, Nevalainen TJ. Bactericidal group IIA phospholipase A2 in serum of patients with bacterial infections. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1767–1772. doi: 10.1086/340821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gronroos JO, Salonen JH, Viander M, Nevalainen TJ, Laine VJ. Roles of group IIA phospholipase A2 and complement in killing of bacteria by acute phase serum. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62:413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nevalainen TJ, Eerola LI, Rintala E, Laine VJ, Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Time-resolved fluoroimmunoassays of the complete set of secreted phospholipases A2 in human serum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1733:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weinrauch Y, Elsbach P, Madsen LM, Foreman A, Weiss J. The potent anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity of a sterile rabbit inflammatory fluid is due to a 14-kD phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:250–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI118399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koduri RS, Gronroos JO, Laine VJ, Le Calvez C, Lambeau G, Nevalainen TJ, et al. Bactericidal properties of human and murine groups I, II, V, X, and XII secreted phospholipases A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5849–5857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harwig SS, Tan L, Qu XD, Cho Y, Eisenhauer PB, Lehrer RI. Bactericidal properties of murine intestinal phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:603–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI117704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piris-Gimenez A, Paya M, Lambeau G, Chignard M, Mock M, Touqui L, et al. In vivo protective role of human group IIA phospholipase A2 against experimental anthrax. J Immunol. 2005;175:6786–6791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elsbach P, Weiss J, Levy O. Integration of antimicrobial host defenses: role of the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:324–328. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Degousee N, Ghomashchi F, Stefanski E, Singer A, Smart BP, Borregaard N, et al. V, and X phospholipases A2s in human neutrophils role in eicosanoid production and Gram-negative bacterial phospholipid hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5061–5073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bingham CO, III, Fijneman RJA, Friend DS, Goddeau RP, Rogers RA, Austen KF, et al. Low molecular weight group IIA and group V phospholipase A2 enzymes have different intracellular locations in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31476–31484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim DK, Fukuda T, Thompson BT, Cockrill B, Hales C, Bonventre JV. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid phospholipase A2 activities are increased in human adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1995;269:L109–L118. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.1.L109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chilton FH, Averill FJ, Hubbard WC, Fonteh AN, Triggiani M, Liu MC. Antigen-induced generation of lyso-phospholipids in human airways. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2235–2245. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Masuda S, Murakami M, Mitsuishi M, Komiyama K, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, et al. Expression of secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes in lungs of humans with pneumonia and their potential prostaglandin-synthetic function in human lung-derived cells. Biochem J. 2005;387:27–38. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zallen G, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Tamura DY, Barkin M, Stockinger H, et al. New mechanisms by which secretory phospholipase A2 stimulates neutrophils to provoke the release of cytotoxic agents. Arch Surg. 1998;133:1229–1233. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Birts CN, Barton CH, Wilton DC. A catalytically independent physiological function for human acute phase protein group IIA phospholipase A2: cellular uptake facilitates cell debris removal. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5034–5045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balestrieri B, Hsu VW, Gilbert H, Leslie CC, Han WK, Bonventre JV, et al. Group V secretory phospholipase A2 translocates to the phagosome after zymosan stimulation of mouse peritoneal macrophages and regulates phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6691–6698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508314200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitsuishi M, Masuda S, Kudo I, Murakami M. Group V and X secretory phospholipase A2 prevents adenoviral infection in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2006;393:97–106. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim JO, Chakrabarti BK, Guha-Niyogi A, Louder MK, Mascola JR, Ganesh L, et al. Lysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by a specific secreted human phospholipase A2. J Virol. 2007;81:1444–1450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01790-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitsuishi M, Masuda S, Kudo I, Murakami M. Human group III phospholipase A2 suppresses adenovirus infection into host cells: evidence that group III, V and X phospholipase A2s act on distinct cellular phospholipid molecular species. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seilhamer JJ, Randall TL, Johnson LK, Heinzmann C, Klisak I, Sparkes RS, et al. Novel gene exon homologous to pancreatic phospholipase A2: sequence and chromosomal mapping of both human genes. J Cell Biochem. 1989;39:327–337. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240390312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen Y, Dennis EA. Expression and characterization of human group V phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1394:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sawada H, Murakami M, Enomoto A, Shimbara S, Kudo I. Regulation of type V phospholipase A2 expression and function by proinflammatory stimuli. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:826–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van der Helm HA, Aarsman AJ, Janssen MJ, Neys FW, van den Bosch H. Regulation of the expression of group IIA and group V secretory phospholipases A2 in rat mesangial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1484:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomas G, Bertrand F, Saunier B. The differential regulation of group IIA and group V low molecular weight phospholipases A2 in cultured rat astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10876–10886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamaguchi K, Kuwata H, Yoshihara K, Masuda S, Shimbara S, Oh-ishi S, et al. Induction of distinct sets of secretory phospholipase A2 in rodents during inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1635:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohtsuki M, Taketomi Y, Arata S, Masuda S, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, et al. Transgenic expression of group V, but not group X, secreted phospholipase A2 in mice leads to neonatal lethality because of lung dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36420–36433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Natarajan R, Nadler JL. Lipid inflammatory mediators in diabetic vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1542–1548. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133606.69732.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murakami M, Koduri RS, Enomoto A, Shimbara S, Seki M, Yoshihara K, et al. Distinct Arachidonate-releasing functions of mammalian secreted phospholipase A2s in human embryonic kidney 293 and rat mastocytoma RBL-2H3 cells through heparan sulfate shuttling and external plasma membrane mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10083–10096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ni Z, Okeley NM, Smart BP, Gelb MH. Intracellular actions of group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 and group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 contribute to arachidonic acid release and prostaglandin production in rat gastric mucosal cells and transfected human embryonic kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16245–16255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513874200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fleisch JH, Armstrong CT, Roman CR, Mihelich ED, Spaethe SM, Jackson WT, et al. Recombinant human secretory phospholipase A2 released thromboxane from guinea pig bronchoalveolar lavage cells: in vitro and ex vivo evaluation of a novel secretory phospholipase A2 inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:252–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Murakami M, Shimbara S, Kambe T, Kuwata H, Winstead MV, Tischfield JA, et al. The functions of five distinct mammalian phospholipase A2s in regulating arachidonic acid release type IIa and type V secretory phospholipase A2s are functionally redundant and act in concert with cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14411–14423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mounier CM, Ghomashchi F, Lindsay MR, James S, Singer AG, Parton RG, et al. Arachidonic acid release from mammalian cells transfected with human groups IIA and X secreted phospholipase A2 occurs predominantly during the secretory process and with the involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2- J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25024–25038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Han WK, Sapirstein A, Hung CC, Alessandrini A, Bonventre JV. Cross-talk between cytosolic phospholipase A2{alpha} (cPLA2{alpha}) and secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) in hydrogen peroxide-induced arachidonic acid release in murine mesangial cells: sPLA2 regulates cPLA2{alpha} activity that is responsible for arachidonic acid release. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24153–24163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim YJ, Kim KP, Han SK, Munoz NM, Zhu X, Sano H, et al. Group V phospholipase A2 induces leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils through the activation of group IVA phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36479–36488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Munoz NM, Kim YJ, Meliton AY, Kim KP, Han SK, Boetticher E, et al. Human group V phospholipase A2 induces group IVA phospholipase A2-independent cysteinyl leukotriene synthesis in human eosinophils. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38813–38820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Akiba S, Hatazawa R, Ono K, Kitatani K, Hayama M, Sato T. Secretory phospholipase A2 mediates cooperative prostaglandin generation by growth factor and cytokine independently of preceding cytosolic phospholipase A2 expression in rat gastric epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21854–21862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuwata H, Fujimoto C, Yoda E, Shimbara S, Nakatani Y, Hara S, et al. A novel role of group VIB calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2{gamma}) in the inducible expression of group IIA secretory PLA2 in rat fibroblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20124–20132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Satake Y, Diaz BL, Balestrieri B, Lam BK, Kanaoka Y, Grusby MJ, et al. Role of group V phospholipase A2 in zymosan-induced eicosanoid generation and vascular permeability revealed by targeted gene disruption. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16488–16494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313748200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Henderson WR, Jr, Chi EY, Bollinger JG, Tien Yt, Ye X, Castelli L, et al. Importance of group X-secreted phospholipase A2 in allergen-induced airway inflammation and remodeling in a mouse asthma model. J Exp Med. 2007;204:865–877. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fujioka D, Saito Y, Kobayashi T, Yano T, Tezuka H, Ishimoto Y, et al. Reduction in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in group X secretory phospholipase A2-deficient mice. Circulation. 2008;117:2977–2985. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Touqui L, Arbibe L. A role for phospholipase A2 in ARDS pathogenesis. Mol Med Today. 1999;5:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arbibe L, Koumanov K, Vial D, Rougeot C, Faure G, Havet N, et al. Generation of lyso-phospholipids from surfactant in acute lung injury is mediated by type-II phospholipase A2 and inhibited by a direct surfactant protein A-phospholipase A2 protein interaction. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1152–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nakos G, Kitsiouli E, Hatzidaki E, Koulouras V, Touqui L, Lekka ME. Phospholipases A2 and platelet-activating-factor acetylhydrolase in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:904–905. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000158519.80090.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Furue S, Mikawa K, Nishina K, Shiga M, Ueno M, Tomita Y, et al. Therapeutic time-window of a group IIA phospholipase A2 inhibitor in rabbit acute lung injury: correlation with lung surfactant protection. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:719–727. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Curfs DM, Ghesquiere SA, Vergouwe MN, van der Made I, Gijbels MJ, Greaves DR, et al. Macrophage secretory phospholipase A2 group X enhances anti-inflammatory responses, promotes lipid accumulation, and contributes to aberrant lung pathology. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21640–21648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Masuda S, Murakami M, Komiyama K, Ishihara M, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, Kudo I. Various secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes are expressed in rheumatoid arthritis and augment prostaglandin production in cultured synovial cells. FEBS J. 2005;272:655–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA. Brain phospholipases A2: a perspective on the history. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;71:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun GY, Xu J, Jensen MD, Simonyi A. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:205–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300016-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Minami T, Tojo H, Shinomura Y, Matsuzawa Y, Okamoto M. Increased group II phospholipase A2 in colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1593–1598. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Haapamäki MM, Grönroos JM, Nurmi H, Alanen K, Nevalainen TJ. Gene expression of group II phospholipase A2 in intestine in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:713–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hanasaki K, Yokota Y, Ishizaki J, Itoh T, Arita H. Resistance to endotoxic shock in phospholipase A2 receptor-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32792–32797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lambeau G, Barhanin J, Schweitz H, Qar J, Lazdunski M. Identification and properties of very high affinity brain membrane-binding sites for a neurotoxic phospholipase from the taipan venom. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11503–11510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lambeau G, Schmid-Alliana A, Lazdunski M, Barhanin J. Identification and purification of a very high affinity binding protein for toxic phospholipases A2 in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9526–9532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lambeau G, Lazdunski M. Receptors for a growing family of secreted phospholipases A2. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:162–170. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Higashino Ki, Yokota Y, Ono T, Kamitani S, Arita H, Hanasaki K. Identification of a soluble form phospholipase A2 receptor as a circulating endogenous inhibitor for secretory phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13583–13588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kundu GC, Mukherjee AB. Evidence that porcine pancreatic phospholipase A2 via its high affinity receptor stimulates extracellular matrix invasion by normal and cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2346–2353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zvaritch E, Lambeau G, Lazdunski M. Endocytic properties of the M-type 180-kDa receptor for secretory phospholipases A(2) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:250–257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yokota Y, Notoya M, Higashino Ki, Ishimoto Y, Nakano K, Arita H, et al. Clearance of group X secretory phospholipase A2 via mouse phospholipase A2 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:250–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cupillard L, Mulherkar R, Gomez N, Kadam S, Valentin E, Lazdunski M, et al. Both group IB and group IIA secreted phospholipases A2 are natural ligands of the mouse 180-kDa M-type receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7043–7051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Saegusa J, Akakura N, Wu CY, Hoogland C, Ma Z, Lam KS, et al. Pro-inflammatory secretory phospholipase A2 type IIA binds to integrins alpha Vbeta 3 and alpha 4beta 1 and induces proliferation of monocytic cells in an integrin-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2008;in press:M804835200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 121.Williams KJ, Tabas I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:551–561. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tabas I, Williams KJ, Boren J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 2007;116:1832–1844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ross R. Cell biology of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:791–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G. Potential involvement of type II phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1997;132:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kugiyama K, Ota Y, Takazoe K, Moriyama Y, Kawano H, Miyao Y, et al. Circulating levels of secretory type II phospholipase A2 predict coronary events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1999;100:1280–1284. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ivandic B, Castellani LW, Wang XP, Qiao JH, Mehrabian M, Navab M, et al. Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis: increased atherogenesis and altered lipoproteins in transgenic mice expressing group IIa secretory phospholipase A2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1284–1290. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tietge UJ, Maugeais C, Cain W, Grass D, Glick JM, de Beer FC, et al. Overexpression of secretory phospholipase A2 causes rapid catabolism and altered tissue uptake of high density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester and apolipoprotein A-I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10077–10084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.de Beer FC, Connell PM, Yu J, de Beer MC, Webb NR, van der Westhuyzen DR. HDL modification by secretory phospholipase A2 promotes scavenger receptor class B type I interaction and accelerates HDL catabolism. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1849–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Webb NR, Bostrom MA, Szilvassy SJ, van der Westhuyzen DR, Daugherty A, de Beer FC. Macrophage-expressed Group IIA sPLA2 increases atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:263–268. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000051701.90972.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tietge UJ, Pratico D, Ding T, Funk CD, Hildebrand RB, Van Berkel T, et al. Macrophage-specific expression of group IIA sPLA2 results in accelerated atherogenesis by increasing oxidative stress. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1604–1614. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400469-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ghesquiere SA, Gijbels MJ, Anthonsen M, van Gorp PJ, van der Made I, Johansen B, et al. Macrophage-specific overexpression of group IIa sPLA2 increases atherosclerosis and enhances collagen deposition. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:201–210. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400253-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kimura-Matsumoto M, Ishikawa Y, Komiyama K, Tsuruta T, Murakami M, Masuda S, et al. Expression of secretory phospholipase A2s in human atherosclerosis development. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rosengren B, Jönsson-Rylander A-C, Peilot H, Camejo G, Hurt-Camejo E. Distinctiveness of secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA and V suggesting unique roles in atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Webb NR. Secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes in atherogenesis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:341–344. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000169355.20395.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hanasaki K, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, Ishimoto Y, Saiga A, Ono T, et al. Potent modification of low density lipoprotein by group X secretory phospholipase A2 is linked to macrophage foam cell formation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29116–29124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sartipy P, Camejo G, Svensson L, Hurt-Camejo E. Phospholipase A2 modification of lipoproteins: potential effects on atherogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;507:3–7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wooton-Kee CR, Boyanovsky BB, Nasser MS, de Villiers WJ, Webb NR. Group V sPLA2 hydrolysis of low-density lipoprotein results in spontaneous particle aggregation and promotes macrophage foam cell formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:762–767. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122363.02961.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Boyanovsky BB, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR. Group V secretory phospholipase A2-modified low density lipoprotein promotes foam cell formation by a SR-A- and CD36-independent process that involves cellular proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32746–32752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ishimoto Y, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, Ono T, Notoya M, Hanasaki K. Group V and X secretory phospholipase A2s-induced modification of high-density lipoprotein linked to the reduction of its antiatherogenic functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1642:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Karabina SA, Brocheriou I, Le Naour G, Agrapart M, Durand H, Gelb M, et al. Atherogenic properties of LDL particles modified by human group X secreted phospholipase A2 on human endothelial cell function. FASEB J. 2006;20:2547–2549. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6018fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Flood C, Gustafsson M, Pitas RE, Arnaboldi L, Walzem RL, Boren J. Molecular mechanism for changes in proteoglycan binding on compositional changes of the core and the surface of low-density lipoprotein-containing human apolipoprotein B100. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:564–570. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000117174.19078.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bostrom MA, Boyanovsky BB, Jordan CT, Wadsworth MP, Taatjes DJ, de Beer FC, et al. Group V secretory phospholipase A2 promotes atherosclerosis: evidence from genetically altered mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:600–606. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257133.60884.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gelb MH, Jain MK, Berg OG. Inhibition of phospholipase A2. FASEB J. 1994;8:916–924. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.12.8088457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]