Abstract

We describe the case of a 23-year-old gentleman who developed a severe generalised necrotising myopathy. Initially presenting with features of a virus-induced polymyositis, both symptomatic and biochemical improvements were initially achieved with glucocorticoid-based immunosuppression. Subsequently he represented with evidence of severe generalised rhabdomyolysis (creatinine kinase peaking at 210,000 U/L). Rendered anuric from the myogloburic assault, he required intensive care support from the development of multi-organ failure. Subsequent investigations failed to demonstrate an infective, inflammatory, metabolic or inherited aetiology. Muscle biopsy demonstrated severe generalised necrotising myopathy in the notable absence of inflammation. Confidential discussion with the patient and relatives confirmed a suspicion of anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) abuse. There is limited literature as to the toxic effect of AAS compounds on muscle tissue, and these tend to focus on localised disease. Indeed, AAS have consistently been shown in animal models to produce a generalised myotrophic state. Apart from the social uses of such compounds, the scope for their supervised use in various medical conditions has been established since the 1960s.

Keywords: Myopathy, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Myositis, MDMA, Anabolic Steroid

A 23-year-old gentleman, with an unremarkable medical history presented with a 1-week history of coryzal symptoms and generalised myalgia. A reduced quantity of dark urine production was also noted, and there were no features of autoimmune disease. Born in Sri Lanka, there was no recent history of foreign travel and no significant family history. He denied the use of recreational drugs, and only occasionally used alcohol modestly. On physical examination he was found to be a well-muscled gentleman, with a painful proximal myopathy of both the upper and lower limbs; otherwise, the examination was grossly unremarkable.

Creatinine kinase (CK) on admission was 28519 U/L. With a preceding history of an upper respiratory tract infection, a clinical diagnosis of polymyositis and rhabdomyolysis was made. Supportive therapy was directed. Immunosuppression was introduced with prednisolone 80 mg od. Admission investigations failed to demonstrate an infective or inflammatory aetiology (Table 1). Intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/5 days) was introduced to which he symptomatically improved, as did his markers of rhabdomyolysis. An in-patient electromyelogram and muscle biopsy was performed (detailed later); and he was subsequently discharged on prednisolone 60 mg od. CK upon discharge was 13652 U/L.

Table 1.

Summary of significant investigations

| Haematology (admission) | CRP < 5 mg/L, ESR < 10 mm/h |

| Biochemistry (admission) | TFTS normal, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests normal |

| ACE normal | |

| Microbiology/virology | Viral tites including entero IgM (Coxsackie A/B, Echo), polio- Not diagnostic |

| HIV antibody, p24 -ve (admission) | |

| HbsAg, Hep C antibody testing -ve | |

| Blood cultures on admission and representation -ve | |

| Urinary drug screen | As per hospital protocol -ve including MDMA, cocaine |

| EMG/NCS | Described in the text |

| Muscle biopsy | As detailed in text and picture |

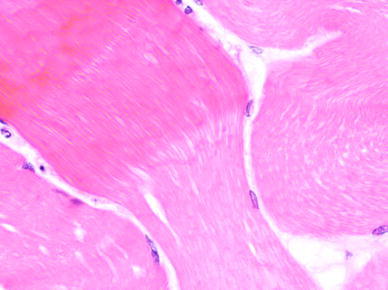

| Picture 1 | Pale necrotic fibre with several hypereosinophilic hypercontracted fibres |

Three days later he represented with a recurrence of severe generalised myalgia and weakness. CK on representation was 52459 U/L. Intravenous methylprednisolone was again utilised. He subsequently developed a progressive weakness affecting the larynx and was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) due to concerns over his airway patency. A CT scan of the chest revealed no neck or mediastinal mass. Due to a worsening metabolic acidosis secondary to renal failure, and fatiguing of the respiratory muscles he was electively intubated and ventilated.

This gentleman had a protracted admission to the ICU for 37 days. Supportive cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and gastrointestinal care was required. He remained dependent on dialysis due to renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis. CK continued to rise to a maximum of 210,000 U/L. Methylprednisolone was stopped, and hydrocortisone introduced to avoid further myelotoxicity. His ICU admission was associated with several line and chest associated septic episodes; as well as the development of the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). He developed several episodes of large bowel obstruction which required decompression with sigmoidoscopy and/or rectal tube insertion. There was no obvious lesion or volvulus seen upon endoscopy, or electrolyte inbalance to explain these repeated episodes. Of interest, his serum was noted to be hypertriglyceridemic several times; this was repeated off propofol which is known to have high triglyceride content.

On Day 37 of his ICU admission, he developed signs of recurrent obstruction with an increasingly distended abdomen. This compromised his ventilation, and was associated with a worsening metabolic acidosis. With the suspicion of an ischaemic event to the bowel he underwent an emergency laparotomy. A perforated gastric ulcer with peritoneal faecal soiling was seen, in addition to small bowel ischaemia. The patient suffered a cardiac arrest which was unresponsive to advanced cardio-pulmonary resuscitation intra-operatively.

We propose that this gentleman’s extreme rhabdomyolysis is secondary to anabolic androgenic steroid (AAS) use. Throughout the course of this case an aetiological factor was sought. His initial presentation was clinically consistent with a viral polymyositis, with a history of a preceding upper respiratory tract infection. Admission investigations did not support the diagnosis of an infective (Table 1) or inflammatory process (RF, ANA, ANCA negative). He did, however, improve clinically and biochemically following the introduction of steroids and supportive treatment. A bacterial or viral aetiology was excluded (Table 1), as was an inflammatory/auto-immune disease. Metabolic markers were not consistent with an underlying pathology to account for this gentleman’s extreme rhabdomyolysis (Table 1).

Nerve conduction studies demonstrated normal sensory and motor conduction from both the upper and lower limbs. The electromyelogram, however, showed myopathic changes in all the muscles sampled with evidence of an acute inflammatory process. Subsequent muscle biopsy revealed no evidence of inflammatory myositis, inclusion body myositis, dermatomyositis, metabolic or mitochondrial myositis; only muscle fibre necrosis in the notable absence of inflammation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Muscle biopsy—see Table 1

Standard urinary drug screen was negative including MDMA (Table 1). A urinary anabolic screen was considered too late in the diagnostic process. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed to delineate the cause of a raised troponin (likely due to renal failure); this demonstrated left ventricular hypertrophy, which in a young individual may represent anabolic androgenic steroid use. Confidential discussions with both the patient’s family and friends confirmed the suspicion of anabolic steroid use. It would appear he had become interested in the social applications of anabolic steroid use, and his physique had significantly changed in the last year. Direct questioning of the patient prior to his death produced a severe stress response.

Muscle is an exceptionally sensitive tissue to toxins and drugs due to its high metabolic rate and various points of interaction [1]. The wide spectrum of disease caused by drugs and toxins include myalgia and myopathy to myositis, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure. Drug induced myopathies represent a distinct subgroup of myopathies that differ in terms of their pathological mechanisms [2]. This group of disorders is of great interest to the clinician as the disease progress may be limited or reversed by treatment of the underlying cause [3]. Toxic myopathies also serve as excellent experimental models in relation to muscle research. Toxic myopathies may be divided into six groups [2]. These are necrotizing myopathy, vacuolar myopathy, inflammatory myopathy, mitochondrial myopathy, steroid myopathy and hypokalaemic myopathy [2].

Body-builders, athletes and other sporting professions have used anabolic steroids for several decades as an aid to build muscle mass and strength [4]. Anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) achieve a supra-physiological testosterone state, prolonging its action in vivo [5]. AAS have a wide physiological range of action. AAS use is associated with numerous side effects which are in general a dose-related phenomenon; therefore, it is the groups which use these in large doses that are most susceptible. These include masculination in women and children, hepatic and lipid impairment and behavioural changes such as aggression [5]. Anabolic steroid use is well associated with the development of left ventricular hypertrophy [7].

The beneficial use of anabolic steroids in medicine is a developing area of clinical interest [6]. These include HIV-related muscle wasting, as well as other catabolic disease states such as chronic obstructive airway disease [5] and the prevention glucocorticoid induced myopathy. Other conditions of note include hereditary angioedema, and certain growth failure syndromes in children. The use of AAS should be undertaken with extreme care by medical professionals, with vigilance to the development of side-effects.

In regard to muscle disease, AAS is associated with a myotrophic state. The published literature suggests an association between localised rhabdomyolysis such as the tricep and deltoid muscles, and the use of AAS [7, 8]. In these cases muscle pain was associated with rhabdomyolysis; however, the development of renal failure was averted with supportive measures including optimisation of fluid balance and forced alkaline diuresis. Research using animal models has demonstrated that anabolic steroids induce apoptosis on differentiated skeletal muscle [9].

The muscle biopsy in this patient demonstrated evidence of extensive necrotising myositis. This is usually associated with drug therapy such as fibrates and statins [2]; however, as described anabolic steroids may cause both local and generalised muscle disease.

Therefore in conclusion we propose by the exclusion of other potential aetiological causes, this gentleman’s extensive necrotising myositis, and resulting severe rhabdomyolysis is a manifestation of anabolic androgenic steroid toxicity. There is limited literature as to the potential toxic effect of androgenic anabolic steroids on differentiated skeletal muscle, apart from a few case reports which describe localised myopathy. Animal models have indeed demonstrated the ability of such agents to induce a generalised myopathic state. The potentially beneficial effects of androgenic anabolic steroids in a medical setting have been well recognised since the 1960s. There appears to be an increasing amount of published literature in regards to emerging areas to which these compounds may be suitable. This case also serves to highlight the toxic effects of such agents, and why these should be prescribed and monitored by a medical practitioner.

Acknowledgments

Dr DG O’Donovan and KM Kurian, Consultant Neuropathologists for providing muscle biopsy photograph.

References

- 1.Walsh RJ, Amato AA. Toxic myopathies. Neurol Clin. 2005;23(2):397–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coquet M, Bannwarth B, Henin D. Drug-induced and toxic myopathies. Rev Prat. 2001;51(3):278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sieb JP, Gillessen T. Iatrogenic and toxic myopathies. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27(2):142–156. doi: 10.1002/mus.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascuzzi RM. Drugs and toxins associated with myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1998;10(6):511–520. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahidi NT. A review of the chemistry, biological action, and clinical applications of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin Ther. 2001;23(9):1355–1390. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kicman AT. Pharmacology of anabolic steroids. J Pharmacol. 2008;154(3):502–521. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goubier JN, Hoffman OS, Oberlin C. Exertion induced rhabdomyolysis of the long head of the triceps. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):150–151. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farkash U, Shabshin N, Pritsch M. Rhabdomyolysis of the deltoid muscle in a bodybuilder using anabolic-androgenic steroids: a case report. J Athl Train. 2009;44(1):98–100. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Shakra S, Alhalabi MS, Nachtman FC, Schemidt RA, Brusilow WS. Anabolic steroids induce injury and apoptosis of differentiated skeletal muscle. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47(2):186–197. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970115)47:2<186::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]