Abstract

H1N1 is known to induce fulminant courses in youths and young adults. We report the case of a 24-year gravida 4 para 2 with singleton pregnancy admitted to obstetrical unit for fever up to 38°C during the 20th week of a so far uncomplicated pregnancy. Ultrasound examination and urine test was inconspicuous. Throat complaints were initially relieved during antibiotic therapy, but the patient developed dyspnea with progressing signs of cyanosis. Intubation was necessary on the fifth day because of decreasing oxygen saturation. Coincidentally, progressive pancytopenia and increased inflammatory activity was recorded. Echocardiography, blood cultures, and bronchial lavage brought no pathological findings, but CT revealed acute respiratory distress syndrome and hepatomegaly. Recent human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalic virus, herpes simplex virus, classical influenza and parainfluenza infections were excluded. An H1N1-infection was confirmed by PCR on the sixth day. The antiviral therapy was changed from zanamivir to oseltamivir. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was necessary due to insufficient oxygen saturation by mechanical ventilation. Until this time, pregnancy seemed to be unimpaired, but a sudden spontaneous expulsion of the fetus occurred on the seventh day (weight 460 g, no anomalies detectable). Curettage post abortem was not necessary. As a result of the antiviral therapy, H1N1-DNA was not detectable at day 16. Despite all endeavors, the respiratory situation could not be improved significantly; the patient additionally developed multiorgan failure during the time course and died on the 28th day of treatment. The recent case illustrates a very dangerous and imposing course of an H1N1-infection during pregnancy.

Keywords: H1N1, Influenza, Pregnancy, ARDS, Germany

Introduction

It is well documented that the H1N1 pandemic spread with high speed. The initial symptoms of a new H1N1-infection were often unspecific. During the time-course of the pandemic, it became obvious that the H1N1-virus seldom causes severe illness [1]. H1N1 is known to induce fulminant courses in youths and young adults [1]. However, as described for other infectious diseases—e.g., the seasonal flu—pregnant women are at a higher risk of infection than the rest of the population. The frequency of complications and dangerous courses is also higher among pregnant women [1]. The early start of an anti-viral therapy is essential for successful treatment. Therefore, the diagnosis of an H1N1-infection should be made as swiftly as possible [1].

Case report

Anamnesis: a 24-year-old gravida 4 para 2 developed a sudden fever ranging up to 38°C during the 20th week of a so far uncomplicated pregnancy. The patient reported a history of mild chronic bronchitis and smoking. Clinical findings: the patient suffered from upper respiratory tract symptoms (throat complaints and cough). The physical examination of heart, lung and abdomen revealed no pathological findings except a pain at both renal beds. Ultrasound examination and urine test was inconspicuous. Circulation and oxygenation was normal. There were no signs of meningism or neurological deficits. All pregnancy related findings were inconspicuous. The patient progressively developed dyspnea with cyanosis. Throat complaints were relieved during antibiotic therapy with Cefuroxim and Erythromycin. However, the patient proceeded to develop respiratory insufficiency and had to be intubated on the fifth day due to rapidly decreasing oxygen saturation. Coincidentally, a progressive pancytopenia and increasing inflammatory activity was recorded. Echocardiography, blood cultures, and bronchial lavage brought no pathological findings, but CT revealed ARDS and hepatomegaly (see Fig. 1). Recent human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalic virus, herpes simplex virus, classical influenza and parainfluenza infections were excluded. An H1N1-infection was confirmed by PCR on the sixth day. The antiviral therapy was changed from zanamivir to oseltamivir on the ninth. On the fifth day after admission to the hospital extracorporeal membrane, oxygenation became necessary because of insufficient oxygen saturation by mechanical ventilation. At this time, the course of pregnancy seemed to be unimpaired. The fetus was suddenly spontaneously expulsed on the seventh day (weight 460 g, no anomalies detectable). In the absence of bleeding, curettage post abort was not necessary. As a result of the antiviral therapy, H1N1-DNA was not detectable at day 16. Despite all the efforts, the respiratory situation was not improved significantly.

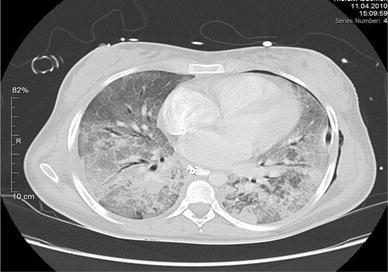

Fig. 1.

Computer tomographic image of the ARDS in the reported patient

Indeed, the patient additionally developed multiorgan failure which ended lethally on the 28th day of treatment.

Discussion

The recent case report illustrates a fulminant course of an H1N1-infection. This provides further evidence to the notion that pregnant women are at a high risk for dangerous and complicated courses of H1N1-infections: H1N1 has a predilection for younger pregnant women. The maternal age of severe (H1N1) infections ranged from 15 to 44 years (median age 26 years) and with more than two parity and gravidity in their history [2]. Most women were in the first or second trimester of pregnancy [2]. Comorbidities–here, a mild chronic bronchitis–increase the risk for a severe course of the H1N1-infection [2, 3]. In this recent case, the patient was hospitalized with clinical symptoms of a pyelonephritis gravidarum although bacteriuria was not detected. However, the initial course of therapy seemed to indicate the correctness of the diagnosis since several symptoms and laboratory values improved antibiotic therapy. The diagnosis of H1N1 infections was delayed because important symptoms were masked by other common pregnancy complications.

Therefore the patient developed severe dyspnea which resulted in respiratory insufficiency within 5 days.

At this time, the diagnosis of an H1N1 infection could be confirmed and the antiviral therapy initiated. It is well known that early introduction of anti-viral therapy (oseltamivir or zanamivir) improves the chances for successful treatment of patients that are high at risk. It should be kept in mind that the time from symptom onset to initial presentation for clinical care usually ranges from 1 to 7 days (median 3.5 days [2]). In median, antiviral treatment is started at 6.5 days [3]. Delayed treatment is associated with admission to an intensive care unit or death [3]. 19% of the intensive care unit admissions in relation to pregnancy are due to ARDS [4]. Severe pneumonia and ARDS are the most important complications of influenza [2, 3, 5]. ARDS secondary to influenza A (H1N1) infection is characterized by severe hypoxemia and need for mechanical ventilation, but there is no preferred mode of ventilation for ARDS in pregnancy [6]. Altogether, 226,136 laboratory-confirmed influenza A (H1N1) virus infections were announced in Germany until April 2010 [5].

33,300 women of these cases were in women between 17 and 49 years, as reported in Germany until March 2010. Four hundred ninety six of them were pregnant. Of these cases, two lethal courses were made that were generally known to the Robert Koch Institution [5].

Information concerning morbidity and mortality were not systematically collected in Germany [5]. Altogether, 258 patients died because of an H1N1 infection during the flu period 2009/2010 [7].

In Brazil 2009, 146 deaths of pregnant women were made known during the pandemic period [8]. Between April and June 2009, 19 hospitalized patients of 272 died in the USA. Sixteen percent of them were pregnant [5]. In the United States, the mortality rate is calculated to be 8% for a group of pregnant women during the influenza H1N1 epidemic [2].

Vaccination is projected to close this gap, as it was shown to be safe for pregnant women after the first trimester. In contrast to the last season the standard vaccine for 2010/2011 contains antigens of A-(H1N1)v-2009 virus [5]. Furthermore, it is clear that H1N1-vaccination has, if at all, only mild side-effects. Examples for side-effects might be local reaction, myalgia, headache and symptoms of a cold, which usually disappear within a few days.

Another positive effect of immunization during pregnancy might be the surrogate immunity of the neonate [5]. The acquired immunity should protect the infant from severe courses of the disease including otitis media and pneumonia.

There is no evidence that the vaccination of pregnant women has an influence on the frequency of preterm delivery or Cesarean section. The vaccination does not increase the risk of an abortion [5].

Regarding the fact that H1N1 will occur during the next flu periods [9], vaccination should be offered to every pregnant women.

Conclusion

Pregnant women consult their gynaecologist not only for gynaecological diseases. Therefore, all differential diagnostic infections should be considered in addition to classical infections which accumulate during pregnancy.

In summary, one should treasure that pregnant women are at high risk for severe causes of H1N1-infections [2, 10] and antiviral treatment should be started early [2, 3] to avoid complications like ARDS.

Furthermore, vaccination is recommended in pregnant women to prevent H1N1 infections and their possibly severe complications.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of actual or potential conflict of interest with respect to this article.

References

- 1.Landt S, Sina F, Kimming R, Schmidt M. H1N1-pregnancy as risk factor. Z Geburtsh Neonatol. 2010;214:48–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamieson D, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie JK, et al. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasquez DN, Estenssore E, Cahales HS, Reina R, Saenz MG, Das Neves A. Clinic characteristics and outcomes of Obstetric patients requiring ICU admission. Chest. 2007;131:718–724. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RKI Änderung der Empfehlung zur Impfung der Influenza. Epid Bull. 2010;31:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jahromi GS, Zand F, Khosravi A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with H1N1 influenza during pregnancy. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19(4):465–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsches Ärzteblatt (2011) Höhepunkt der Grippewelle überschritten. dapd/aerzteblatt.de. http://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/44838/ (Accessed February 2011)

- 8.Jimenenz MF, El Beitune P, Salcedo MP, Von Ameln AV, Mastalir FP, Braun LD. Outcome for pregnant women infected with influenza A (H1N1) virus during the 2009 pandemic in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;111(3):217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (2010) ECDC forward look risk assessment. Likely scenarios for influenza in 2010 and the 2010/2011 influenza season in Europe and the consequent work priorities. ECDC. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/H1N1/Documents/1003_RA_forward_look_influenza.pdf (Accessed October 2010)

- 10.ANZIC Influenza Investigators and Australasian Maternity Outcomes Surveillance System (2010) Critical illness due to 2009 A/H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women: population based cohort study. BMJ 340:c1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]