Abstract

Influenza related to complications such as pneumonia and encephalitis have sporadically been reported. However, influenza A (H1N1)-virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS) has rarely been reported. A 39-year old woman complained of high fever and was referred to us. Chest infiltrations in both lungs and a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimen was confirmed and she was diagnosed with influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia. Pancytopenia was found, and hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) was diagnosed by bone marrow aspiration. Following intravenous administration of antiflu drug and combination therapy of steroid pulse and erythromycin IV, the patient’s respiratory dysfunction and lab data gradually improved and she was discharged on day 21. Whereas secondary HPS related to viral infections such as Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus type 6 are commonly seen, H1N1 pneumonia complicated with secondary VAHS is rare.

Keywords: Influenza A (H1N1), Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, Pneumonia

Introduction

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is a clinical condition characterized by macrophages and activated histiocytes, leading to uncontrolled phagocytosis of erythrocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, and precursor cells. HPS is classified as primary or secondary, the latter being more frequent [1]. Some fatal cases caused by some types of influenza A, such as H3N2 or H5N1, complicated with HPS have sporadically been reported [2–4]. We present a successfully treated case of severe influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia complicated with virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS) by combination therapy of steroid pulse and erythromycin IV, which is the first such case ever reported as far as we know. Physicians should recognize the presence of VAHS caused by influenza A (H1N1), which could result in poor outcomes.

Case report

A 39-year old woman presented with the chief complaint of high fever for the previous 3 days and was referred to us. She had a history of rheumatic arthritis, which did not require medication. Chest radiography demonstrated infiltrates in both lung fields. Chest computed tomography (CT) also revealed ground-grass opacities scattered all over the lung (Figs. 1 and 2). Although no subjective respiratory symptoms were experienced, she had severe respiratory failure with oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 78% (room air) at first visit, and oxygen therapy was started with noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV). Flu-antigen tests twice consecutively were both negative. Bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was performed. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in BALF specimen confirmed a result positive for novel swine-origin influenza A (N1H1), and she was diagnosed with influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia. She exhibited pancytopenia without any subjective symptoms (Table 1). HPS was diagnosed by bone-marrow aspiration (Fig. 3). Therapies were begun with Peramivir 600 mg/day for 5 days for influenza infection and combination therapy of steroid pulse and erythromycin 1,000 mg/day IV for 5 days for acute respiratory failure and H1N1-associated HPS. Her respiratory function gradually recovered, and NPPV was discontinued on day 3. Pancytopenia was also cured by day 14 without any symptoms. Enteral administration of steroid following IV administration was started with oral prednisolone 60 mg/day, and the dose was reduced to 30, 20, and 15 mg per day every 3 days and was discontinued on day 15. She was discharged on day 21.

Fig. 1.

Chest radiography shows diffuse ground-grass opacities bilaterally, with predominance in both lower lung fields and enlargement of cardiothoracic ratio

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography (CT) scan shows marked ground-grass opacities scattered all over the lung

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Test | Value |

|---|---|

| Hematology | |

| WBC | 2,100/μl |

| Neu | 79.3% |

| Eos | 0.0% |

| Bas | 0.5% |

| Lymp | 16.9% |

| Mon | 2.9% |

| RBC | 337 × 104/μl |

| Hb | 10.6 g/dl |

| HCT | 31.6% |

| PIT | 10.1 × 104/μl |

| Blood coagulation | |

| PT | 76.4% |

| aPTT | 27.9% |

| INR | 1.15 |

| Biochemistry | |

| TP | 7.0 g/dl |

| Alb | 3.3 g/dl |

| T-Bili | 0.5 mg/dl |

| AST | 69 IU/l |

| ALT | 54 IU/l |

| LDH | 438 IU/l |

| ALP | 271 IU/l |

| γ-GTP | 57 IU/l |

| BUN | 14 mg/dl |

| Cr | 0.8 mg/dl |

| Na | 138 mEq/l |

| K | 3.8 mEq/l |

| Cl | 107 mEq/l |

| PG | 96 mg/dl |

| Fe | 17 μg/dl |

| TIBC | 232 μg/dl |

| Ferritin | 199.7 ng/ml |

| T-cho | 111 mg/dl |

| TG | 100 mg/dl |

| HDL | 25 mg/dl |

| LDL | 71 mg/dl |

| Serology | |

| CRP | 10.8 mg/dl |

| BNP | 111.4 |

| Blood gas analysis (mask 10 l/min) | |

| pH | 7.418 |

| PO2 | 60.4 Torr |

| PCO2 | 34.2 Torr |

| HCO3 − | 21.5 mmol/l |

| BE | −2.5 mmol/l |

| Sputum culture | |

| Normal flora | |

| Blood culture | (−) |

| Urinary antigen | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | (−) |

| Legionella | (−) |

WBC white blood cells, Neu neutrophils, Eos eosinophils, Bas basophil, Lymp lymphocyte, Mon monocytes, RBC red blood cells, HCT hematocrit, PIT plasma iron turnover, PT prothrombin time, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, INR international normalized ratio, TP total protein, Alb albumin, T-Bili , AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, ALP alkaline leukocyte phosphatase, γ-GTP gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Na sodium, Cr creatinine, K potassium, Cl chlorine, PG phosphatidylglycerol, Fe iron, TIBC total iron-binding capacity, Tcho, TG triglycerides, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, CRP C-reactive protein, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, pH hydrogen ion concentration, PO 2 oxygen pressure, PCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide, HCO 3 − bicarbonate, BE

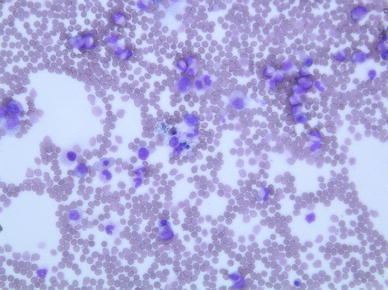

Fig. 3.

Bone marrow smear shows macrophages with hemophagocytosis

Discussion

Whereas many viruses such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus type 6 (HHV-6) and -8 are associated with HPS [5], the pathophysiological mechanism for HPS remains unknown. Generally, influenza patients suffer greatly from general fatigue, high fever, and systemic arthritis. Therefore, symptoms associated with HPS may be masked. Physicians are aware of the presence of severe complications of influenza, such as pneumonia, encephalitis, asthma attack, and myocarditis [6]. However, influenza viruses, including the H1N1 virus, are not considered to be pathogens of VAHS. As pancytopenia could result in fatality, complete blood count should cautiously be monitored, even though pancytopenia might be induced by drugs or by benign disease. Long-term neutropenia would increase the risk of severe bacterial infections. Thrombocytopenia could result in spontaneous bleeding, which can occur in the central nervous system with a fatal outcome. Severe anemia could contribute to organ dysfunction, such as heart failure and tissue hypoxia. It has previously been reported that HPS developed disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ dysfunction resulting in high mortality rates [7].

Beutel et al. [8] demonstrated that critically ill patients with H1N1 might commonly be complicated by VAHS. Such patients showed a high mortality rate compared with those without VAHS. Thus, the origin of pancytopenia with H1N1 pneumonia should never fail to be investigated, even with such invasive examination as bone marrow aspiration or biopsy, as it could result in fatality.

VAHS is associated with many cytokines, releasing a cytokine storm. In addition, the plasma level of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 or IL-10 in H1N1 patients who died or who had acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are higher compared with that in patient with less severe illness [9]. There might be a correlation between cytokine storm and influenza pneumonia resulting in ARDS or VAHS. In addition, the severity of influenza infection could be related to the patient’s cytokine levels. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of the presence of influenza pneumonia complicated with VAHS, which could result in poor outcomes.

We administered a combination of steroid pulse therapy and erythromycin IV, as well as an antiflu drug. As a result, the patient’s respiratory dysfunction and pancytopenia rapidly improved. Some physicians previously reported that macrolides could be effective in preventing and treating acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis (CB) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [10, 11]. It is evident that macrolides decrease neutrophil chemotaxis and infiltration into the respiratory epithelium down-regulate adhesion molecule expression and enhance neutrophil apoptosis [12, 13]. Theoretically, it is reasonable that erythromycin could demonstrate its immunomodulatory effect rather than its antimicrobial one in this case.

Whereas the efficacy of prednisolone or plasma exchange has been demonstrated [14], the standard treatment of VAHS is not yet established. Martin et al. [15] reported that early use of corticosteroid therapy does not favorably affect the outcome and that it only increases the risk of infections. On the other hand, a few animal reports have described that high-dose steroids were effective in reducing pulmonary lesions and suppressing cytokines, which led to shutdown of macrophage activation [16–18]. More cases need to be studied and investigated regarding corticosteroid therapy for severe influenza infection, including VAHS. The limitation of our report is that the plasma concentration of cytokines was not examined.

In conclusion, we suggest that physicians be aware of the possibility that VAHS could be complicated with severe influenza infection. Pancytopenia should be monitored, otherwise, it may result in poor outcomes. We believe that combination therapy of steroid pulse and macrolides would be effective in treating HPS complicated with H1N1 pneumonia. The standard therapy of VAHS is not yet established, and more cases must be studied and investigated.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the diligent and thorough critical reading of our manuscript by Mr. John Wocher, Executive Vice President and Director, International Affairs/International Patient Services, Kameda Medical Center (Japan); and Mr. Michael Burke, Summer, intern from the University of Iowa at Kameda Medical Center.

References

- 1.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:601–608. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.To KF, Chan PK, Chan KF, Lee WK, Lam WY, Wong KF, et al. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. J Med Virol. 2001;63:242–246. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<242::AID-JMV1007>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henter JI, Chow CB, Leung CW, Lau YL. Cytotoxic therapy for severe avian influenza A (H5N1) infection. Lancet. 2006;367:870–873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter MN, Foot ABM, Oakhill A. Influenza-A and the virus associated hemophagocytic syndrome—cluster of 3 cases in children with acute-leukemia. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:297–299. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neofytou E, Sourvinos G, Asmarianaki M, Spandidos DA, Makrigiannakis A. Prevalence of human herpes virus types 1–7 in the semen of men attending an infertility clinic and correlation with semen parameters. Fertil Steril. 2008;85:420–421. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asai N, Ohkuni Y, Komatsu A, Matsunuma R, Nakashima K, Ando K, et al. A case of asthma complicated influenza myocarditis. J Infect Chemother. 2010;10:13. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellinger RP. Inflammation and coagulation: implications for the septic patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1259–1265. doi: 10.1086/374835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beutel G, Wiesner O, Eder M, Hafer C, Schneider AS, Kielstein JT, et al. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome as a major contributor to death in patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection. Crit Care. 2011;5(2):R80. doi: 10.1186/cc10073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;362:1708–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milstone AP. Use of azithromycin in the treatment of acute exacerbation of COPD. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2008;3:515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asai N, Ohkuni Y, Iwasaki T, Matsunuma R, Nakashima K, Otsuka Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-dose 2.0 g azithromycin in the treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Chemother. 2011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Koch CC, Esteban DJ, Chin AC, Olson ME, Read RR, Ceri H, et al. Apoptosis, oxidative metabolism and interleukin-8 production in human neutrophils exposed to azithromycin: effects of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:19–26. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amsden GW, Baird IM, Simon S, Treadway G. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin vs levofloxacin in the outpatient treatment of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2003;123(3):772–777. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aouba A, Noguera ME, Clauvel JP, Quint L. Haemophagocytic syndrome associated with plasmodium vivax infection. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:832–833. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin-Loeches I, Lisboa T, Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Silva E, Sprung C, et al. Use of early corticosteroid therapy on ICU admission in patients affected by severe pandemic (H1N1)v influenza A infection. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(2):272–83. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter MJ. A rationale for using steroids in the treatment of severe cases of H5N1 avian influenza. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:875–883. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottolini M, Blanco J, Porter D, Peterson L, Curtis S, Prince G. Combination anti-inflammatory and antiviral therapy of influenza in a cotton rat model. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:290–294. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottolini MG, Blanco JC, Eichelberger MC, Porter DD, Pletneva L, Richardson JY, Prince GA. The cotton rat provides a useful small-animal model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2823–2830. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]