Abstract

Background

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) deficiency is a rare immunodeficiency that is characterized by recurrent hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and splenomegaly and sometimes associated with refractory inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative therapy, the outcomes of HSCT for XIAP deficiency remain unsatisfactory compared with those for SLAM-associated protein deficiency and familial HLH.

Aim

To investigate the outcomes and adverse events of HSCT for patients with XIAP deficiency, a national survey was conducted.

Methods

A spreadsheet questionnaire was sent to physicians who had provided HSCT treatment for patients with XIAP deficiency in Japan.

Results

Up to the end of September 2016, 10 patients with XIAP deficiency had undergone HSCT in Japan, 9 of whom (90%) had survived. All surviving patients had received a fludarabine-based reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen. Although 5 patients developed post-HSCT HLH, 4 of them survived after etoposide administration. In addition, the IBD associated with XIAP deficiency improved remarkably after HSCT in all affected cases.

Conclusion

The RIC regimen and HLH control might be important factors for successful HSCT outcomes, with improved IBD, in patients with XIAP deficiency.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10875-016-0348-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, inflammatory bowel disease, reduced intensity conditioning, XIAP deficiency, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome

Introduction

X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome (XLP) is a rare inherited immunodeficiency characterized by an extreme vulnerability to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, frequently resulting in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) [1]. Major clinical phenotypes of XLP include fulminant infectious mononucleosis or EBV-associated HLH (∼60%), lymphoproliferative disorder (∼30%), and dysgammaglobulinemia (∼30%) [2, 3]. The responsible gene was first identified as that encoding the SH2D1A or SLAM-associated protein (SAP), located in the region of Xq25 [3–6]. In another cohort of patients with EBV-driven HLH, mutations in the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) gene (also known as the baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 4 (BIRC4) gene) were identified [7]. Although the SH2D1A and XIAP genes are close together on Xq25, the molecular pathogenesis and clinical features of these diseases seem to be distinct [8, 9]. XIAP is a potent inhibitor of programmed cell apoptosis, blocking the activated forms of the effector caspases 3, 7, and 9 via its BIR2 and 3 domains [10]. Patients with XIAP deficiency are often affected with HLH, splenomegaly, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), variable hypogammaglobulinemia, and autoinflammatory phenomena. Monocytes from patients with XIAP deficiency are impaired in their ability to secrete cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-10, IL-8, and MCP-1) in response to stimulation with nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) ligands. NOD2 is the strongest genetic risk factor associated with Crohn’s disease [11–13]. Thus, one of the characteristic symptoms of XIAP deficiency is IBD. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative treatment for XIAP deficiency. However, HSCT for XIAP deficiency has been associated with a poor prognosis compared with that for SAP deficiency [14, 15], as demonstrated by a retrospective international survey of 19 XIAP-deficient patients who were treated with the procedure [15]. This study revealed that treatment with reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) resulted in apparently better prognosis than treatment with myeloablative conditioning (MAC), where 6 of 11 patients in the RIC group survived, as opposed to only 1 of 7 patients in the MAC group. The 1-year probabilities of survival were 14% for the MAC group and 57% for the RIC group. The major causes of death were hepatic veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary toxicity in the MAC group and pneumonia, respiratory failure, and ongoing HLH in the RIC group. To investigate the outcomes and adverse events of HSCT for Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency, we conducted a national survey and identified a total of 29 patients with the disorder from 19 unrelated families, including previously reported patients [16–18]. Of the 10 patients who underwent HSCT, 9 (90%) have survived.

Material and methods

Data collection

A spreadsheet questionnaire was sent to physicians who had provided treatment to patients with XIAP deficiency in Japan. Patients 1 and 3 were previously reported [17, 19]. All patients and families provided informed consent for genetic analyses in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

Outcome and variable definitions

The day of HSCT was defined as day 0. The first of the 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 0.5 × 109/L or more was defined as the day of engraftment. Primary graft failure was defined as failure to maintain an ANC of 0.5 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days after HSCT, by day 28 with bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood stem cell grafts or by day 42 with cord blood (CB) grafts [20]. Secondary graft failure was defined as initial engraftment followed by a decline of donor cells to <5% [21]. Engraftment and chimerism of whole blood were measured using either XY fluorescence in situ hybridization for sex-mismatched donors or variable number of tandem repeat analysis for same-sex donors. Full and mixed chimerisms were described by detection of >95 and 5–95% of donor hematopoietic stem cells in the recipient’s BM or peripheral blood, respectively [22]. Conditioning regimens were classified as MAC if they contained an alkylating agent (busulfan 16 mg/kg) or total body irradiation (TBI) at a dose that would not allow autologous BM recovery. Conditioning regimens were classified as RIC if they did not meet the definition of the MAC regimen [23]. If there was uncertainty regarding the intensity of the regimen (patient 1), it was classified as an intermediate intensity regimen. Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and chronic GVHD were graded according to the standard criteria [24, 25]. The probability of survival was estimated through the Kaplan-Meier method. We used all patient data for determining the probability of survival, except for patient 10 whose observation period was too short to evaluate long-term survival. Infection or reactivation of viruses including EBV, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and adenovirus was periodically monitored by the antigenemia or quantitative PCR methods.

Results

Characteristics of the Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency

Twenty-nine patients with XIAP deficiency were identified from 19 families in Japan. The characteristics of these patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Twenty-three of the 29 patients (79%) developed HLH. Thirteen patients (45%) were affected by IBD by 16 years of age, with the age at IBD onset ranging from 4 months to 16 years. The cumulative percentage of patients who experienced IBD is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

HSCT in the Japanese Patients with XIAP Deficiency

Ten of the 29 patients had undergone HSCT by the end of September 2016 in Japan. The median age at HSCT was 7.8 years (range 1.1–16 years). The indication for HSCT was active HLH in 4 patients, refractory IBD in 5 patients, and both HLH and IBD in 1 patient. The patient characteristics and XIAP mutations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency

| Patient | ID | XIAP mutation | Age at onset | HLH | HLH treatment | IBD | IBD treatment | HSCT indication | Age at HSCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.1 | R381X | 7 months |

8 months–1 year (until HSCT) |

DEX, CsA, Eto | – | – | HLH | 1 year |

| 2 | 8 | R222X | 4 months |

4 months–2 year (until HSCT) |

PSL,DEX, Eto | – | – | HLH | 2 years |

| 3 | 1 | R238X | 1 year | 1–4 years | DEX, CsA | 7 years | PSL, CsA, MMF, 5-ASA, tocilizumab | IBD | 7 years |

| 4 | 11 | Q492X | 8 years | 11 years, 12 years | DEX | 8 years | PSL, Tac, 5-ASA, infliximab |

HLH IBD |

13 years |

| 5 | 13 | R381X | 6 years | – | – | 6 years | PSL, Tac, 5-ASA, 6-MP, infliximab | IBD | 10 years |

| 6 | 5.2 | N341YfsX7 | 1 year 3 months | 1–2 years | PSL | 14 years | PSL, Tac, 5-ASA, 6-MP, infliximab | IBD | 16 years |

| 7 | 2.3 | R381X | 8 mo |

8 months, 1 year 6 months |

DEX, CsA | – | – | HLH | 2 years |

| 8 | 14 | c.1099 + 1, g > a | 1 month | – | – | 1 month | PSL, Tac, 5-ASA,AZP | IBD | 1 year |

| 9 | 15.2 | Del of exon 2-3 | 1 year | 1–2 years 5 months | PSL, CsA, Eto | – | – | HLH | 2 years |

| 10 | 18 | M1V | 12 years | 2 years, 4 years | PSL | 12 years |

PSL, CsA, 5-ASA, AZP, infliximab, adalimumab, ileostomy |

IBD | 15 years |

HLH hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, ND no data, DEX dexamethasone, Eto etoposide, PSL prednisolone, CsA cyclosporine A, Tac tacrolimus, 5-ASA mesalazine, 6-MP 6-mercaptopurine, AZP azathioprine

The graft characteristics and conditioning regimens are shown in Table 2. The graft source was unrelated BM in 6 patients, related BM in 1 patient, and CB in 4 patients. Four patients received fully matched related (n = 1) and unrelated (n = 3) grafts based on 8 HLA antigens (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-DRB1). Five patients received single-allele mismatched unrelated grafts, and 1 patient (patient 5) received 3 allele mismatched CB.

Table 2.

Transplantation procedures and acute GVHD in the Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency

| Patient | ID | Graft HLA match | Graft source | Total cell count (cells/kg) | CD34+ cell count (cells/kg) | Conditioning regimen (mg/m2 or mg/kg) | ATG (mg/kg) | GVHD prophylaxis | Acute GVHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.1 | 7/8 (C) | CB | 1.01 × 108 | 1.96 × 105 | Flu 125, Mel 80, CY 140, TBI 6Gy | – | MTX, Tac | |

| 2 | 8 | 8/8 | CB | 7.63 × 107 | 2.56 × 105 | Eto 300, Flu 180, Mel 140, TBI 4Gy | 5 | Tac | I (skin 1) |

| 3 | 1 | 8/8 | URBM | 3.46 × 108 | N/A | Flu 150, Mel 70, TLI 3Gy | 1.25 | MTX, Tac | III (gut 2, skin 3) |

| 4 | 11 | 7/8 (A) | URBM | 2.6 × 108 | 2.7 × 106 | Flu 150, Mel140, TBI 4Gy | – | MTX, Tac | I (skin 2) |

| 5 | 13 | 5/8 (A, C, DR) | CB | 4.4 × 107 | 1.1 × 105 | Flu 150, CY 120, TBI 4Gy | – | MTX, Tac | I (skin 2) |

| 6 | 5.2 | 8/8 | RBM | 1.85 × 108 | N/A | Eto 300, Flu 150, Mel 140, TBI 3Gy | – | MTX, Tac | I (skin 1) |

| 7 | 2.3 | 7/8 (C) | URBM | 5.8 × 108 | N/A | Flu 150, Mel 140, TBI 3Gy | – | MTX, Tac | – |

| 8 | 14 | 7/8 (DR) | CB | 1.14 × 108 | 1.49 × 105 | Eto 100, Flu 150, Mel 140, TLI 3Gy | – | MTX, Tac | I (skin 1) |

| 9 | 15.2 | 7/8 (DR) | URBM | 3.66 × 108 | N/A | Eto 200, Flu 150, Mel 140, TBI 4Gy | 5 | MTX, Tac | – |

| 10 | 18 | 8/8 | URBM | 1.43 × 108 | 1.73 × 106 | Eto 200, Flu 150, Mel 140, TBI 3Gy | 2.5 | MTX, Tac | I (skin 1) |

ATG antithymocyte globulin, GVHD graft versus host disease, CB cord blood, N/A not available, URBM unrelated bone marrow, RBM related bone marrow, Flu fludarabine, Mel melphalan, CY cyclophosphamide, TBI total body irradiation, Eto etoposide, TLI total lymphoid irradiation, MTX methotrexate, Tac tacrolimus

Nine patients received RIC, and 1 patient (patient 1) received intermediate intensity conditioning including fludarabine, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, and TBI 6 Gy. Fludarabine (150–180 mg/m2), melphalan (70–140 mg/m2), and a low dose (3–4 Gy) of TBI or total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) with or without anti-thymocyte globulin were performed in 8 patients (patients 2–4 and 6–10). Patient 5 received fludarabine (150 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), and TBI 4 Gy. Etoposide (total 100–300 mg/m2) was additionally administered to 5 patients (patients 2, 6, 8, 9, and 10) as a preconditioning regimen. The GVHD prophylaxis regimen was tacrolimus and methotrexate in 9 patients, and tacrolimus only in 1 patient.

Eight patients (80%) experienced HLH before HSCT, and 2 of them were not relieved until the conditioning regimen was started. Six patients (60%) suffered from IBD, and all were refractory to conservative IBD treatment, which became the indication for HSCT.

All surviving patients were engrafted for a median of 20.3 days (range 11–26 days). Eight patients (89%) maintained full donor type chimerism, and only patient 10 developed mixed chimerism of 83% donor type. There were no primary or secondary graft failures in this cohort.

The HSCT-related adverse events are shown in Table 3. Five patients developed post-HSCT HLH, 4 of whom were treated with etoposide and dexamethasone palmitate (DP) or prednisolone. Five patients (patients 2, 6, 8, 9, and 10) were given etoposide as a conditioning regimen, and 2 of them (patients 6 and 9) developed post-HSCT HLH, whereas 4 of 6 patients without etoposide administration developed this condition. Seven patients were complicated with acute GVHD, but 6 of them showed only skin GVHD. Only one patient (patient 3) developed grade III acute GVHD (gut 2, skin 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes in the Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency post-HSCT

| Patient | ID | Engraftment (days) | Chimerism | Virus reactivation | Adverse event | IBD post-HSCT | HLH post-HSCT | Outcome | Months after HSCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.1 | 22 | N/A | – | ARDS | – | + | Dead | 27 days |

| 2 | 8 | 16 | 98.8% | – | Catheter infection (Staphylocuccus epidermidis) | – | – | PS0 | 45 months |

| 3 | 1 | 18 | >95% | – | ATG-anaphylaxis | – | + (Eto, DP) | PS0 | 36 months |

| 4 | 11 | 23 | 100% | – | Adrenal failure | – | – | PS0 | 25 months |

| 5 | 13 | 11 | 98.6% | HHV6-encephalitis, BK virus cystitis | – | – | + (Eto, PSL) | PS1 with mechanical ileus | 23 months |

| 6 | 5.2 | 26 | 100% | BK viremia JC viremia | Sepsis (Escherichia coli) | – | + (Eto, DP) | PS0 | 19 months |

| 7 | 2.3 | 20 | >95% | – | TMA, PAH | – | – | PS1 with TMA | 14 months |

| 8 | 14 | 26 | 100% | CMV-emia | – | – | – | PS1 with LPD | 12 months |

| 9 | 15.2 | 22 | 99.7% | – | MOF | – | + (Eto, DP) | PS0 | 12 months |

| 10 | 18 | 19 | 83% | BK virus cystitis, CMV-emia | Enteritis (Enterobacter) | – | – | PS1 | 5 months |

HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, HLH hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, N/A not available, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, ATG anti-thymocyte globulin, Eto etoposide, DP dexamethasone palmitate, HHV6 human herpesvirus 6, TMA thrombotic microangiopathy, PAH pulmonary artery hypertension, CMV cytomegalovirus, LPD lymphoproliferative disease, MOF multiple organ failure, DEX dexamethasone, PSL prednisolone, PS performance status

Outcomes of HSCT

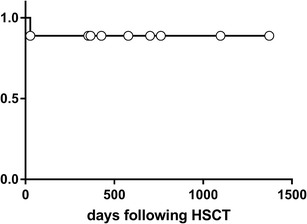

Nine of the 10 patients are currently alive and well at a median of 21.2 months (range 5–45 months) after HSCT, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status 0 or 1 (Table 3). Patient 1, who received intermediate intensity conditioning, died on day 27 post-HSCT from complications due to engraftment syndrome, HLH, and acute respiratory distress syndrome [17]. Except for patient 10, who was followed for 5 months only, we evaluated the probability of survival in the other 9 patients to be 89% (Fig. 1). Although patient 7 (a sibling of patient 1) developed thrombotic microangiopathy and pulmonary artery hypertension, he improved after administration of phosphodiesterase inhibitors and plasma exchange.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses for the Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency. Long-term survival in patients treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

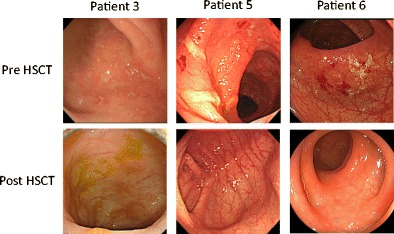

Colonoscopic Findings in the Patients Associated with IBD

Intriguingly, 6 patients (patients 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10) were associated with IBD before HSCT, all cases of which improved remarkably after HSCT and maintained remission without any treatments. IBD was relieved during the conditioning regimen in all patients, at least by the point of engraftment. Colonoscopic findings for patients 3, 5, and 6 are shown in Fig. 2. Colonoscopy before HSCT revealed multiple ulcers and bleeding in the sigmoid colon, whereas that after HSCT showed improvement to normal colon appearance.

Fig. 2.

Colonoscopy results of three Japanese patients with XIAP deficiency. Colonoscopic findings are shown for patients 3, 5, and 6 before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). They revealed multiple ulcers before HSCT, but showed a normal bowel mucosa after the procedure

Virus Infection after HSCT

Six patients had no virus infection or reactivation, but 4 patients developed virus reactivation, including human herpesvirus 6, BK virus, JC virus, and CMV. They were successfully treated with antiviral drugs or improved without medication.

Discussion

XLP (SAP deficiency and XIAP deficiency) is a rare but life-threatening disease. A large cohort study showed that most patients with XLP died by the age of 40 years, and more than 70% of the patients had died before the age of 10 years mainly as a result of fulminant infectious mononucelosis and HLH [2]. Although HSCT is the only curative treatment for XIAP deficiency, the result of a previous study revealed that transplantation outcomes were apparently poorer than those for SAP deficiency [15].

An international survey reported that 55% of patients with XIAP deficiency developed HLH, and 26% were affected by IBD [26]. In a Japanese survey, 79% of patients developed HLH (Supplementary Table 1). Although this HLH frequency is higher than the international average, it is equivalent to those in France (25/35, 71%) and the USA (9/11, 82%). Twelve patients (41%) developed IBD up to the age of 16 years, and this percentage is relatively higher than those in other countries (9–33%) [26]. The occurrence of IBD in XIAP deficiency might be associated with ethnic background.

In this study, 10 of the patients underwent HSCT, and 9 of them survived. The transplantations were performed in different institutions, but all conditioning regimens were RIC, except that for patient 1, who was given an intermediate intensity regimen, but died of HLH and acute respiratory distress syndrome on day 27 post-HSCT, in which virus infection or reactivation might not be involved. Thus, the intensity of conditioning might be linked to survival. In the case of HSCT for patients with XIAP deficiency, RIC was apparently superior to MAC [15]. Successful HSCT outcomes based on RIC for XIAP-deficient patients have been reported in several studies [19, 27, 28]. Patients 1, 5, and 7 had the same R381X mutation, and they developed fatal or severe regimen-related complications, indicating a possible association of gene mutation with the severity of disease. The probability of survival after HSCT was 89%, and the outcome was better than that reported by a previous study, although the follow-up period was limited. It is possible that RIC and HLH control might contribute to the better outcome of HSCT for XIAP deficiency. The high level of donor chimerism in all surviving patients was remarkable, although all of them underwent the RIC regimen. A previous international survey reported that 55% of patients on a RIC regimen of fludarabine, melphalan, and alemtuzumab developed mixed chimerism [15]. In our study, the RIC regimen consisted of fludarabine, melphalan, and low-dose TBI or TLI, and only 1 patient developed mixed chimerism. Therefore, low-dose TBI or TLI might contribute to a high level of donor chimerism.

Five of the 10 patients (50%) developed HLH after HSCT. HLH induced by uncontrolled macrophage activation is often a fatal complication after HSCT and frequently leads to primary and secondary graft failures. Thus, prophylaxis of post-HSCT HLH might play an important role in successful HSCT outcomes. Since DP decreases the viability of primary human macrophages via glucocorticoid receptors in the cytoplasm, it is considered effective for the prevention of post-HSCT HLH [29]. In addition, etoposide can be considered as a preconditioning regimen to reduce post-HSCT HLH [30]. In our cohort, post-HSCT HLH developed in 2 of 5 patients (40%) treated with etoposide, whereas 3 of 5 patients (60%) without etoposide treatment developed this condition. Therefore, the use of DP and etoposide could reduce the risk of HLH related to HSCT for XIAP-deficient patients. Alemtuzumab against CD52 was not used for the conditioning regimen in this study owing to its limited usage in Japan. CD52 is highly expressed in monocytes and macrophages, and alemtuzumab administration might reduce the risk of post-HSCT HLH and total doses of etoposide [31].

IBD or hemorrhagic colitis is a characteristic finding in XIAP deficiency. Interestingly, IBD improved remarkably after HSCT in all affected cases and maintained remission without any further treatments for the condition. IBD associated with primary immunodeficiency, including XIAP deficiency or IL-10/IL-10R deficiency, was reported to be remarkably improved after HSCT [19, 32]. In XIAP deficiency, monocytes are impaired in their ability to secrete cytokines mediated by NOD2 stimulation, which may cause IBD. Thus, it is supposed that IBD in XIAP deficiency can be cured by HSCT, based on the transplantation of normal monocytes.

In conclusion, a national survey on XIAP deficiency revealed that the probability of survival after HSCT was prominent, and it is assumed that an RIC regimen and HLH control might be important factors for successful outcomes. In addition, the IBD associated with XIAP deficiency could be cured by HSCT.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 21 kb)

(DOCX 76 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to H.K.) and the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (to T.M).

Authorship Contribution

S.O. and H.K. wrote the manuscript. T.O., A.H., and T.W. performed the immunological and genetic studies. S.O., M.Y., K.H., Y.N., T.I., M.O., H.N., Y.S., and H.T. collected the data. R.K. performed the colonoscopies. M.T., K.I., and T.M. contributed critical discussion. H.K. designed the study.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Absolute neutrophil count

- BIRC4

Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 4

- BM

Bone marrow

- CB

Cord blood

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- DP

Dexamethasone palmitate

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- GVHD

Graft-versus-host disease

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- HLH

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- MAC

Myeloablative conditioning

- NOD2

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2

- RIC

Reduced intensity conditioning

- SAP

SLAM-associated protein

- TBI

Total body irradiation

- TLI

Total lymphoid irradiation

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- XLP

X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Sumegi J, Huang D, Lanyi A, Davis JD, Seemayer TA, Maeda A, et al. Correlation of mutations of the SH2D1A gene and Epstein-Barr virus infection with clinical phenotype and outcome in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2000;96:3118–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seemayer TA, Gross TG, Egeler RM, Pirruccello SJ, Davis JR, Kelly CM, et al. X-linked lymphoproliferative disease: twenty-five years after the discovery. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:471–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tangye SG. XLP: clinical features and molecular etiology due to mutations in SH2D1A encoding SAP. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34:772–9. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey AJ, Brooksbank RA, Brandau O, Oohashi T, Howell GR, Bye JM, et al. Host response to EBV infection in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease results from mutations in an SH2-domain encoding gene. Nat Genet. 1998;20:129–35. doi: 10.1038/2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols KE, Harkin DP, Levitz S, Krainer M, Kolquist KA, Genovese C, et al. Inactivating mutations in an SH2 domain-encoding gene in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13765–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayos J, Wu C, Morra M, Wang N, Zhang X, Allen D, et al. The X-linked lymphoproliferative-disease gene product SAP regulates signals induced through the co-receptor SLAM. Nature. 1998;395:462–9. doi: 10.1038/26683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rigaud S, Fondanèche MC, Lambert N, Pasquier B, Mateo V, Soulas P, et al. XIAP deficiency in humans causes an X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS, Scott FL. Human inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: why XIAP is the black sheep of the family. EMBO Rep. 2006;10:988–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filipovich AH, Zhang K, Snow AL, Marsh RA. X-linked lymphoproliferative syndromes: brothers or distant cousins. Blood. 2010;116:3398–408. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rezaei N, Mahmoudi E, Aghamohammadi A, Das R, Nichols KE. X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome: a genetic condition typified by the triad of infection, immunodeficiency and lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worthey EA, Mayer AN, Syverson GD, Helbling D, Bonacci BB, Decker B, et al. Making a definitive diagnosis: successful clinical application of whole exome sequencing in a child with intractable inflammatory bowel disease. Genet Med. 2011;13:255–62. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182088158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh RA, Bleesing JJ, Chandrakasan S, Jordan MB, Davies SM, Filipovich AH. Reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic cell transplantation is an effective treatment for patients with SLAM-associated protein deficiency/X-linked lymphoproliferative Disease type 1. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1641–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh RA, Rao K, Satwani P, Lehmberg K, Müller I, Li D, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for XIAP deficiency: an international survey reveals poor outcomes. Blood. 2013;121:877–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-432500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, Kanegane H, Nishida N, Imamura T, Hamamoto K, Miyashita R, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of XIAP deficiency in Japan. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:411–20. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9638-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wada T, Kanegane H, Ohta K, Ohta K, Katoh F, Imamura T, et al. Sustained elevation of serum interleukin-18 and its association with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in XIAP deficiency. Cytokine. 2014;65:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, Hoshino A, Taga T, Kunitsu T, Ikeda Y, Yasumi T, et al. A female patient with incomplete hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis caused by a heterozygous XIAP mutation associated with non-random X-chromosome inactivation skewed towards the wild-type XIAP allele. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:244–8. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuma Y, Imamura T, Ichise E, Sakamoto K, Ouchi K, Osone S, et al. Successful treatment of idiopathic colitis related to XIAP deficiency with allo-HSCT using reduced-intensity conditioning. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19:E25–8. doi: 10.1111/petr.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rondon G, Saliba RM, Khouri I, Giralt S, Chan K, Jabbour E, et al. Long-term followup of patients who experienced graft failure postallogeneic progenitor cell transplantation. Results of a single institution analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:859–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischhauer K, Locatelli F, Zecca M, Orofino MG, Giardini C, De Stefano P, et al. Graft rejection after unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for thalassemia is associated with nonpermissive HLA-DPB1 disparity in host-versus graft direction. Blood. 2006;107:2984–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamidieh AA, Pourpak Z, Hosseinzadeh M, Fazlollahi MR, Alimoghaddam K, Movahedi M, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic SCT for pediatric patients with LAD-1: clinical efficacy and importance of chimerism. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:646–50. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HLA-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18:295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman HM, Sale GE, Lerner KG, Barker EA, Weiden PL, Sullivan K, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus-host disease in man. Am J Pathol. 1978;91:545–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguilar C, Latour S. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein deficiency: more than an X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:331–8. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worth AJ, Nikolajeva O, Chiesa R, Rao K, Veys P, Amrolia PJ. Successful stem cell transplant with antibody-based conditioning for XIAP deficiency with refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2013;121:4966–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chellapandian D, Krueger J, Schechter T, et al. Successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in XIAP deficiency using reduced-intensity conditioning. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:355–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiwaki S, Nakayama T, Murata M, Nishida T, Sugimoto K, Saito S, et al. Dexamethasone palmitate successfully attenuates hemophagocytic syndrome after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: macrophage-targeted steroid therapy. Int J Hematol. 2012;95:428–33. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1023-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi R, Tanaka J, Hashino S, Ota S, Torimoto Y, Kakinoki Y, et al. Etoposide-containing conditioning regimen reduces the occurrence of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis after SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:254–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowan WC, Hale G, Tite JP, Brett SJ. Cross-linking of the CAMPATH-1 antigen (CD52) triggers activation of normal human T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1995;7:69–77. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engelhardt KR, Shah N, Faizura-yeop I, Kocacik Uygun DF, Frede N, Muise AM, et al. Clinical outcome in IL-10- and IL-10 receptor-deficient patients with or without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:825–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)

(DOCX 76 kb)