Abstract

Purpose

To examine the IL-8 expression levels and association of genetic variants with the risk of childhood persistent asthma prognosis.

Methods

Overall, 170 asthmatic children and 170 healthy controls were included in this case–control study. The human IL-8 serum levels were measured using ELISA. The IL-8 mRNA expression levels were assessed by a real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) methods.

Results

The IL-8 expression at both protein and mRNA levels was found to be significantly elevated in asthmatic children compared to healthy subjects (P < 0.0001, P = 0.004; respectively). Higher levels of IL-8 mRNA are detected in subjects with moderate to severe asthma. The presence of IL8-251 A/T (rs4073) and + 781C/T (rs2227306) polymorphisms was significantly associated with an increased risk of asthma (P = 0.002, P = 0.036, respectively). In addition, we noted a significant association between these polymorphisms and an elevated risk of atopic asthma (P < 0.05). For rs2227306 SNP, the highest median level of IgE was detected for the presence of TT genotype (865 ± 99.74 IU/mL). Although, the rs4073 polymorphism conferred a higher risk to develop asthma at an advanced stage of severity (P = 0.008). The rs4073 T and rs2227306 C alleles are considered as risk factors for asthma development. The rs4073 T allele is represented also as a risk factor for asthma severity in Tunisian children.

Conclusions

Both IL-8 gene and protein expression may play a key role in asthma pathogenesis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00408-017-0058-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Interleukin-8, SNP, Childhood asthma, qRT-PCR, Atopy, Severity

Introduction

Asthma is a complex respiratory disease. It is one of the most common lung disorders, characterized by a chronic airway inflammation [1]. The airway epithelial cells can produce cytokines and chemokines to initiate immune responses [2]. Asthma is a T-helper type 2 (Th2)-dependent disease associated to a higher production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13, which induces the release of IL-8 from human bronchial epithelial cells [3].

The IL-8 belongs to the superfamily of CXC chemokines, exerts its effect through two receptors, IL-8 receptor alpha (IL-8 RA, CXCR1) and beta (IL-8 RB, CXCR2). IL-8 is a strong chemotactic cytokine that activates the inflammatory cells by the recruitment of neutrophils, mononuclear phagocytes, mast cells, and T cells [4, 5]. IL-8 is involved in the initiation of the acute and chronic inflammatory process [6]. It is implicated in the pathogenesis of several pulmonary diseases like bronchial asthma [7], Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) [8], severe infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [9], and viral bronchiolitis [10]. Various reports have also described the capacity of Th2, Th-9, and Th-17 cells to induce the release of proinflammatory cytokines as the IL-8, which contribute to the expansion of neutrophils to the airway epithelial cells of patients with asthma [3, 11–13]. An increased level of IL-8 was observed in Broncho-alveolar fluid (BALF), sputum, and endobronchial biopsies of patients with asthma [14, 15]. Furthermore, a higher IL-8 serum levels were observed for severe patients with asthma that suggested that IL-8 plays an important role in asthma severity [16]. Therefore, IL-8 might protect against the development of atopic asthma by the inhibition of IgE production [17].

Human IL-8 is encoded by a gene located on chromosome 4q13–q21 and composed of four exons, three introns, and a proximal promoter region [18]. Fifteen IL8 polymorphisms were characterized to date and only two were reported to be associated with altered IL-8 mRNA levels [19]. The IL-8-251A/T (rs4073) polymorphism located on the promoter region, was reported to be associated with an increased IL-8 level. The IL-8 + 781C/T (rs2227306) located within the first intron, was described to promote gene transcription and regulation [20]. Recently, genetic association studies showed that these polymorphisms were associated with susceptibility to inflammatory diseases as RSV bronchiolitis, ARDS, lung cancer, and asthma [7, 9, 21–23].

Our data suggest that IL8 is important in the genetic control of human asthma susceptibility. A recent advance in sequence-specific gene silencing provides a new platform to develop gene-specific drugs for disease management. Then, molecular study of IL8 gene might contribute to elucidate in part the mechanism of asthma development and facilitate in the future the development of new drugs.

The aim of this study was to analyze the association of rs4073 and rs2227306 polymorphisms with the risk of childhood asthma development. We also investigated the correlation of IL-8 protein and mRNA levels with childhood asthma development and disease severity in the Tunisian population.

Methods

Study Population

A total of 170 asthmatic children were recruited between May 2013 and September 2015, from the department of Pediatric and Respiratory Diseases, Abderrahmane MAMI Hospital of Chest Diseases, Ariana, Tunisia. Asthma diagnosis was established according to GINA recommendations [24], based on clinical asthma symptoms and lung function test. The classification of asthma severity was determined on the basis of clinical symptoms and lung function according to GINA guidelines. Only patients whose asthma was controlled were retained.

Our population includes 117 patients diagnosed with atopic asthma and 53 without. All patients were classified according to asthma severity into four groups: a mild intermittent (n = 2), a mild persistent (n = 87), a moderate persistent (n = 70), and a severe persistent asthma (n = 11).

In addition, we recruited a group of 170 age-matched healthy control children from the emergency department of Tunis children hospital for only pathologies related to accidents of daily life such as fractures and without respiratory or allergy manifestations. All controls were free of any infectious symptoms. The inclusion criteria for the control group were as follows: no symptoms or history of asthma, of other pulmonary diseases, of allergy, and of any chronic disease. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of participating children. All data and sample collections for this study were approved by the local ethics committee (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Patients with Asthma n (%) | Healthy individuals n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 170 | 170 |

| Age | ||

| Mean (range) | 9.1 (2–16) | 9.5 (4–15) |

| Categories | ||

| 0–11 years (pediatric children) | 141 (82.94) | 134 (78.82) |

| 12–16 years (adolescent) | 29 (17.05) | 36 (21.17) |

| Sex | ||

| Females (girls) | 61 (36) | 72 (42) |

| Males (boys) | 109 (64) | 98 (58) |

| Atopic status | ||

| Atopic | 117 (68.82) | – |

| Non-atopic | 53 (31.17) | – |

| IgE (mean ± SD) | ||

| > 200 U/ml−1 | 40 (81.63) | – |

| ≤ 200 U/ml−1 | 9 (18.36) | – |

| Smoke exposure | ||

| Passive | 59 (38.06) | – |

| No smoking | 96 (61.63) | – |

| Severity | ||

| Mild intermittent | 2 (1.17) | – |

| Mild persistant | 87 (51.17) | – |

| Moderate persistant | 70 (41.17) | – |

| Severe persistant | 11 (6.47) | – |

All information on tobacco exposure (passive smoking or second-hand smoke, or environmental tobacco smoke) used in this analysis was collected at baseline only for patients. We did not obtain total information from healthy subject parents (the data were missing in more than 20% of patients for tobacco smoking habits in the control group).

The classification of passive and no smoker was based on the information on the active smoking habits status for parent who was never, current, or former smokers. Questions on exposure to passive smoking related to each of the following: “the age at which they started smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the duration of smoking in years at home and at work.” Among former smokers, age at quitting smoking was also collected.

Estimation of Human IL-8 Serum Levels

For the serum preparation, we collect 5 ml of venous blood in a plain tube without anticoagulant and then allowed to clot for about 4 h at room temperature. The serum was separated by centrifugation (1300×g, for 15 min), then was taken and stored at − 80 °C until use. The determination of the IL-8 serum levels was performed in duplicate using a commercially available IL-8 Human ELISA (enzyme linked immunosorbent assay) Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, US) with the use of an ELx 800 Automated Microplate Reader, Bio-Tek Instruments (Winooski, VT). The IL-8 serum level data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SD). A P value < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Determination of Human IL-8 mRNA Levels

The determination of IL-8 mRNA levels of expression was performed by the real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) as we previously reported [25]. The mRNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using TRIZOL® reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) samples were synthesized using random hexamer primers and RNase H-reverse transcriptase (Fermentas). The qRT-PCR was done in a 25 μl reaction using an Applied Biosystems system (AB, Foster City, CA). The reaction systems include 15 μg/μl (2.5 μl) of cDNA template, 10 μM of each forward and reverse primers set and the appropriate dilution of SYBR Green mix (QIAGEN, Germany), and the adequate volume of distilled water (Gibco).

The β-actin mRNA (internal control) was quantified in the same way as the IL-8 mRNA, using the forward and reverse primers 5′-ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGT-3′ and 5′-CCTCTTCAAAAACTTCTCCACACC-3′, respectively, and using the probes: 5′-CAAACATGATCTGGGTCATCTTCTC-3′ and 5′-GCTCGTC GTCGACAACGGCTC-3′.

The qRT-PCR detection system was used for amplification and the employed cycling program was as follows: Initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min; then 40 cycles of a second denaturation step at 94 °C for 15 s; an annealing step at 59 °C for 45 s, and an extension step at 72 °C for 45 s; after that, a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

IL-8 Polymorphisms Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the Salting-out procedure as described [26]. The study of rs4073 and rs2227306 polymorphisms was assessed for 170 patients and 170 controls. The IL-8 SNPs were genotyped using polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP)-based method.

The following primers [Forward: CCATCATGATAGCATCTGT; Reverse: CCACAATTTGGT GAATTATTAA] were used to amplify the 173-bp DNA fragment of the rs4073 polymorphism. The primers [Forward: CTCTAACTCTTTATATAGGAATT; Reverse: GATTGATTTTATCAACAGGCA] were used to amplify the 203-bp DNA fragment of the rs2227306 polymorphism [9]. The PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 100 ng genomic DNA, 0.5 μmol/l of each primer, 200 μmol/l of each dNTP, 10× PCR buffer, 2 mmol/l MgCl2, and 2,5 U of DNA Taq polymerase.

The PCR amplification conditions for the rs4073 polymorphism included an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles with a second denaturation step at 94 °C for 30 s, an annealing step at 60 °C for 55 s, and an extension step at 72 °C for 60 s, then a final extension step at 72 °C for 8 min. The PCR products were digested with 1 U of the restriction enzyme AseI (Fermentas). The rs4073 A allele was identified by 21- and 152-bp fragments and the T allele by a single 173-bp fragment.

However, the procedure of PCR amplification for the rs2227306 region was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 8 min, 35 cycles of denaturing step at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing step at 54 °C for 30 s, extension step at 72 °C for 30 s, and then a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were digested by 1 U of the restriction enzyme EcoRI (MBI Fermentas). The rs2227306 C allele was identified by 19- and 184-bp fragments and the T allele by a single 203-bp fragment. The digested fragments were visualized on an ultraviolet illuminator after separation on a 3% agarose gel stained with 0.1% ethidium bromide.

Statistical Analysis

The genotype frequencies were tested for the deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE).

The association analysis was performed using the open Epi Info Version 6 and 7 software based on a standard Chi-squared test. The P values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant. The strength of a genetic association is indicated by the odds ratio (OR). The OR and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated whenever applicable.

The quantitative statistical analysis was performed by Prism V.5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). The IL-8 expression levels were analyzed by the t test that used to compare the mean values between two groups. The reported P values are two tailed and P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Haploview program version 4.2 was used to calculate the pairwise Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) between the IL8 SNPs. The Haplotype frequencies and effects were performed using Haploview. The P values for the patient–control differences in diplotype distributions were adjusted for multiple tests by Bonferroni correction. Only the allele frequencies of the diplotype > 1% were included in the analyses, those < 1% were excluded.

Results

IL-8 Serum and mRNA Expression Levels

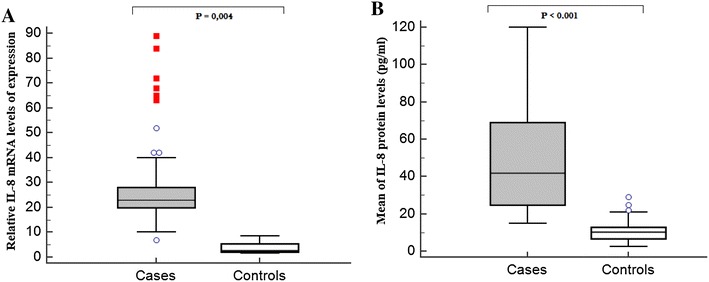

In the current study, we compared the level of IL-8 protein in the serum and mRNA of 170 cases and 170 controls (Fig. 1). The IL-8 serum levels were significantly higher in patient (48.82 ± 27.36 pg/ml) than in control (10.67 ± 4.62 pg/ml; P < 0.0001) group (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

IL-8 expression levels in patients with asthma and healthy controls. a IL-8 mRNA levels in healthy and the asthmatic children. The IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly higher in patient than in control group (P = 0.004); b IL-8 serum levels in healthy and the patients with asthma. The IL-8 serum levels were significantly higher in patient (48.82 ± 27.36) than in control (10.67 ± 4.62) group (P < 0.0001)

No significant difference in PBMC composition between patients with asthma and healthy controls was claimed.

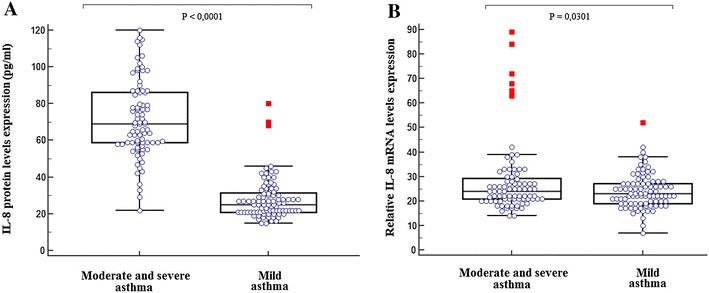

We found that the IL-8 serum concentrations were markedly elevated in children with moderate and severe asthma (n = 81; 71.55 ± 21.09 pg/ml) than those with mild form (n = 89; 28.55 ± 21.14 pg/ml, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Relative expression of IL-8 serum and mRNA levels in patient group, according to asthma severity. a Relative expression of IL-8 was calculated as indicated in the method section. Box plot indicating significant elevated serum levels of IL-8 in asthmatic children with moderate/severe asthma (n = 81; 71.55 ± 21.09) compared to children with mild asthma (n = 89; 28.55 ± 21.14, P < 0.0001). b Relative expression of IL-8 mRNA was calculated as indicated in the method section. Box plot indicating significant elevated IL-8 mRNA levels in asthmatic children with moderate/severe asthma (n = 81) compared to those with mild asthma (n = 89; P = 0.0301)

We also reported in Fig. 1b, a significantly higher IL-8 mRNA levels in patients than in controls (P = 0.004). IL-8 mRNA levels were further increased in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma compared to mild asthma group (P = 0.025) (Fig. 2b).

However, the IL-8 mRNA expression and the distribution of protein levels, according to different IL-8 genotypes for both polymorphisms did not differ significantly in the asthmatic group (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Genotype Analysis of IL-8 Gene

The distribution of rs4073 and rs2227306 genotype frequencies for healthy controls and patients with asthma was in agreement with HWE (data not shown).

We observed a significant difference in the genotype and allele distributions of rs4073 and rs2227306 polymorphisms between asthmatic and healthy children (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of alleles and distribution of genotypes of IL8 polymorphisms in asthmatic and control subjects

| IL-8 SNPs | Genotype | Alleles | Population | χ 2 | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthmatics N = 170(%) | Controls N = 170(%) | ||||||

| rs4073 | 12.36 | 0.002 | |||||

| AA | 13 (7.64) | 31 (18.23) | 1.00a | ||||

| AT | 70 (41.17) | 78 (45.88) | 2.14 (0.98–4.71) | 0.055 | |||

| TT | 87 (51.17) | 61 (35.88) | 3.40 (1.56–7.51) | 0.001 | |||

| A | 96 (28.23) | 140 (41.17) | 1.00b | ||||

| T | 244 (71.76) | 200 (58.82) | 1.78 (1.28–2.48) | 0.0005 | |||

| rs2227306 | 6.64 | 0.036 | |||||

| TT | 12 (7.06) | 27 (15.88) | 1.00a | ||||

| CT | 73 (42.94) | 69 (40.60) | 2.38 (1.06–5.44) | 0.035 | |||

| CC | 85 (50) | 74 (43.52) | 2.58 (1.16–5.85) | 0.018 | |||

| T | 97 (28.53) | 123 (36.18) | 1.00a | ||||

| C | 243 (71.47) | 217 (63.82) | 1.42 (1.01–1.99) | 0.040 | |||

Bold number indicates significant association

OR odds ratio, n number

aReference

For the rs4073, the homozygous TT genotype was more frequent in asthmatic than in control groups (P = 0.002). The presence of this genotype was significantly associated with an increased asthma risk (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.28–2.48). Then, the presence of the rs4073 T allele is considered as a risk factor for asthma development.

The allele and genotype frequencies of rs2227306 were also significantly different between case and control groups, which suggest that the rs2227306 was associated with asthma susceptibility. Our results indicated that the subjects carrying CC or CT genotypes were more exposed to develop asthma compared to those carrying the TT genotype (OR > 2; P = 0.036).

We also analyzed the association of these polymorphisms with atopy. The frequency of the rs4073 TT and rs2227306 CC genotypes differed significantly between children with atopic asthma and healthy controls (P = 0.005 and P = 0.02, respectively). The presence of the rs4073 TT (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.25–2.65) or the rs2227306 CC (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.14–2.47) genotypes was associated with an increased risk to develop atopic asthma (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genotypes distribution and alleles frequencies of IL8 polymorphisms according to atopic status

| Atopy | IL-8 SNPs | Genotypes | Alleles | Population | χ 2 | P | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients N (%) | Controls N (%) | |||||||

| Atopic asthma | ||||||||

| rs4073 | 10.35 | 0.005 | ||||||

| AA | 9 (7.69) | 31 (18.23) | 1.00a | |||||

| AT | 47 (40.17) | 78 (45.88) | 2.45 | 0.11 | 2.08 (0.85–5.17) | |||

| TT | 61 (52.13) | 61 (35.88) | 8.20 | 0.004 | 3.44 (1.42–8.55) | |||

| A | 65 (27.77) | 140 (41.17) | 1.00b | |||||

| T | 169 (72.22) | 200 (58.82) | 10.26 | 0.001 | 1.82 (1.25–2.65) | |||

| rs2227306 | 7.27 | 0.02 | ||||||

| TT | 8 (6.84) | 27 (15.88) | 1.00a | |||||

| CT | 43 (36.75) | 69 (40.60) | 2.20 | 0.13 | 2.10 (0.82–5.56) | |||

| CC | 66 (56.41) | 74 (43.52) | 5.81 | 0.015 | 3.01 (1.20–7.78) | |||

| T | 59 (62.6) | 123 (36.18) | 1.00b | |||||

| C | 175 (37.4) | 217 (63.82) | 7.19 | 0.007 | 1.68 (1.14–2.47) | |||

| Non-atopic asthma | ||||||||

| rs4073 | 4.79 | 0.09 | ||||||

| AA | 4 (7.54) | 31 (18.23) | 1.00a | |||||

| AT | 23 (43.39) | 78 (45.88) | 1.45 | 0.22 | 2.29 (0.67–8.53) | |||

| TT | 26 (49.05) | 61 (35.88) | 3.64 | 0.05 | 3.30 (0.97–12.30) | |||

| A | 31 (29.24) | 140 (41.17) | 1.00b | |||||

| T | 75 (70.75) | 200 (58.82) | 4.37 | 0.03 | 1.69 (1.03–2.79) | |||

| rs2227306 | 4.93 | 0.08 | ||||||

| TT | 4 (7.55) | 27 (15.88) | 1.00a | |||||

| CT | 30 (56.60) | 69 (40.60) | 2.85 | 0.09 | 2.93 (0.87–10.88) | |||

| CC | 19 (35.85) | 74 (43.52) | 0.44 | 0.50 | 1.73 (0.49–6.65) | |||

| T | 38 (35.85) | 123 (36.18) | 1.00a | |||||

| C | 68 (64.15) | 217 (63.82) | 0.00 | 0.95 | 1.01 (0.63–1.64) | |||

Bold number indicates significant association

OR odds ratio, n number

aReference

Subject with at least one copy of rs4073 T allele had more risk to be diagnosed with asthma disease at an advanced stage (P = 0.02; OR 3.68, 95% CI 1.12–13.29) (Supplementary Table 1). Then, the rs4073 T allele is considered as a risk factor for asthma severity in Tunisian children.

Haplotype Frequencies of IL-8 Gene

LD test between IL-8 polymorphisms was estimated by the value of D’ (0.151). The most frequent diplotype in our population was TC (42.6%), but no significant difference was shown between patients and controls (P > 0.05). Therefore, the frequency of the rare diplotype AT was significantly associated with low asthma childhood risk in our population (P C < 0.0004) (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Our results indicated an elevated IL-8 serum and mRNA levels in the Tunisian asthmatic children and particularly for the subjects with moderate/severe asthma. The excessive release of IL-8 in asthmatic group, observed in our study was consistent with many previous findings [27, 28]. In the same way, different studies revealed a positive association between the increased neutrophil count and asthma severity [29, 30]. Then, the reason of the increase in IL-8 levels may be due to the association of the IL-8 to neutrophil recruitment in the lung injury. In fact, human bronchial epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and airway smooth muscle cells recruit neutrophils into the airways by the release of IL-8 and/or other chemokines [13, 31]. IL-8 might participate extensively in the development of airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in asthma [27] and might be used as a biomarker for disease evolution and severity.

In the present case–control study, we also analyzed the association of two IL8 variants with the childhood asthma susceptibility. Our findings suggested that the rs4073 and rs2227306 were strongly associated with an increased childhood asthma risk. These results indicated that the expression of IL-8 genetic polymorphisms could contribute to the pathogenesis of childhood asthma.

Our results represent a replication of previous Heinzmann et al. [7] findings, in the German asthmatic children. The presence of rs4073 was also associated with the risk to develop RSV bronchiolitis [32], acute pancreatitis [33, 34], atrophic gastritis [35], and Behcet’s disease [36]. In contrast, many other studies did not find any significant association with the polymorphism rs4073 and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or lung cancer development [37, 38]. Discrepancies in ethnicities, sample size, and genetic background may have caused the difference in the results of different studies.

Our data indicated a significant association between the rs4073 T allele and the childhood asthma atopy and severity. In fact, previous study indicated that the presence of the rs4073 T was associated with an increased IL-8 levels in the bronchioles contributing to a higher local pulmonary inflammation and then to asthma severity [39].

Genetic polymorphisms may have important functional consequences. These variations are able to influence the expression or the activity of the resulting protein. It has been reported that the two polymorphisms rs4073 and rs2227306 influenced the transcriptional activity of the IL8. Firstly, the expression levels of IL-8 (mRNA and protein) might be influenced by other factors than the only presence of IL-8 variants and the expression of these SNPs might have other effects like the alteration of the expression of a more distant gene in particular SNP situated in the promoter region. Secondly, when SNPs were not studied within the exact haplotype blocks (some SNPs in the same region are in LD with others SNPs), we cannot conclude about the real effect of IL-8 SNPs on the expression of IL-8.

The rs4073 is the most important polymorphism and it is located in the transcription start site [40]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that this polymorphism increases the production of IL-8. Lee et al. [39] have described that the rs4073 T allele possessed a transcriptional activity twofold to fivefold stronger than the rs4073 A allele, which contributed to the high IL–8 amount as described. Additionally, it has been shown that the IL8 promoter DNA sequence around the position–251 was conformed to the binding motif of C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein) [41, 42]. Then, this functional effect might be related to the fact that the nuclear factors such as C/EBP and GATA bind with high affinity to the IL-8 transcription regulatory sites in the presence of the T allele. However, experimental results suggest that the differences in IL-8 expression are not linked directly to the rs4073 polymorphism [36]. Therefore, other SNPs could be implicated in the transcriptional and translational activities.

For the rs2227306, our findings were consistent to report results in asthma and rheumatoid arthritis [7, 43]. In fact, it has been reported that the rs2227306 located in IL8 intron 1, promotes the regulation of gene transcription by a CAAT (cytosine–cytosine–adenosine–adenosine–thymidine) box that locates downstream of rs2227306. Hacking et al. [19] observed that C/EBP β preferentially bound in the presence of the rs2227306 T allele in respiratory epithelial cells. C/EBP β has an important role in the regulation of inflammation, and its binding to the regulatory region in the IL8 gene increases significantly the transcription [20, 44].

In our study, the frequency of the less frequent haplotype AT was significantly associated with low asthma childhood risk in our population (P < 0.0004). In contrast, this haplotype is the more transmitted in patients with bronchiolite, then it represented a significant association with susceptibility to bronchiolitis [40].

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study in the association of rs4073 and rs2227306 polymorphisms with childhood asthma risk in the Tunisian population. Our data confirmed the inflammatory role of IL-8, which could be used as a marker for asthma childhood severity. Further investigation on the IL8 gene variants and their biological functions is also needed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grant from “the Ministry of research of Tunisia: El Manar Tunis University”.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that thay have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Abderrahman Mami Hospital, Ariana, Tunisia; and all participating subjects in this study signed informed consents in this study. All the procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Contributor Information

Rihab Charrad, Phone: +216 22 17 63 38, Email: charrad.rihab@gmail.com.

Wajih Kaabachi, Email: kaabachi.wajih@gmail.com.

Ahlem Rafrafi, Email: rafahlem@yahoo.fr.

Anissa Berraies, Email: anissa-berraies@hotmail.com.

Kamel Hamzaoui, Email: kamel.hamzaoui@gmail.com.

Agnes Hamzaoui, Email: agnes.hamzaoui@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bijanzadeh M, Mahesh PA, Ramachandra NB. An understanding of the genetic basis of asthma. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(2):149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bals R, Hiemstra P. Innate immunity in the lung: how epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(2):327–333. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00098803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stříž I, Mio T, Adachi Y, Robbins R, Romberger D, Rennard S. IL-4 and IL-13 stimulate human bronchial epithelial cells to release IL-8. Inflammation. 1999;23(6):545–555. doi: 10.1023/A:1020242523697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djukanović R. Asthma: a disease of inflammation and repair. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(2):S522–S526. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(00)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boisvert WA, Curnss LK, Terkeltaub RA. Interleukin-8 and its receptor CXCR2 in atherosclerosis. Immunol Res. 2000;21(2–3):129–137. doi: 10.1385/IR:21:2-3:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada A, Sekido N, Akahoshi T, Wada T, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Essential involvement of interleukin-8 (IL-8) in acute inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56(5):559–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinzmann A, Ahlert I, Kurz T, Berner R, Deichmann KA. Association study suggests opposite effects of polymorphisms within IL8 on bronchial asthma and respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(3):671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hildebrand F, Stuhrmann M, van Griensven M, Meier S, Hasenkamp S, Krettek C, Pape H-C. Association of IL-8-251A/T polymorphism with incidence of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and IL-8 synthesis after multiple trauma. Cytokine. 2007;37(3):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puthothu B, Krueger M, Heinze J, Forster J, Heinzmann A. Impact of IL8 and IL8-receptor alpha polymorphisms on the genetics of bronchial asthma and severe RSV infections. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto LA, DE Azeredo Leitão LA, Mocellin M, Acosta P, Caballero M, Libster R, Varga JE, Polack F, Comaru T, Stein RT, DE Souza AP. IL-8/IL-17 gene variations and the susceptibility to severe viral bronchiolitis. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(4):642–646. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816002648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vock C, Hauber HP, Wegmann M. The other T helper cells in asthma pathogenesis. J Allergy (Cairo) 2010;2010:519298. doi: 10.1155/2010/519298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CE, Chan K. Interleukin-17 Stimulates the expression of interleukin-8, growth-related oncogene-α, and granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor by human airway epithelial Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26(6):748–753. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prause O, Laan M, Lötvall J, Lindén A. Pharmacological modulation of interleukin-17-induced GCP-2-, GRO-α-and interleukin-8 release in human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;462(1):193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurashima K, Mukaida N, Fujimura M, Schröder J-M, Matsuda T, Matsushima K. Increase of chemokine levels in sputum precedes exacerbation of acute asthma attacks. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59(3):313–316. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shute JK, Vrugt B, Lindley I, Holgate ST, Bron A, Aalbers R, Djukanović R. Free and complexed interleukin-8 in blood and bronchial mucosa in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(6):1877–1883. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvestri M, Bontempelli M, Giacomelli M, Malerba M, Rossi G, Di Stefano A, Rossi A, Ricciardolo F. High serum levels of tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-8 in severe asthma: markers of systemic inflammation? Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(11):1373–1381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimata H, Yoshida A, Ishioka C, Lindley I, Mikawa H. Interleukin 8 (IL-8) selectively inhibits immunoglobulin E production induced by IL-4 in human B cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176(4):1227–1231. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukaida N, Shiroo M, Matsushima K. Genomic structure of the human monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor IL-8. J Immunol. 1989;143(4):1366–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacking D, Knight J, Rockett K, Brown H, Frampton J, Kwiatkowski D, Hull J, Udalova I. Increased in vivo transcription of an IL-8 haplotype associated with respiratory syncytial virus disease-susceptibility. Genes Immun. 2004;5(4):274–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li K, Yao S, Liu S, Wang B, Mao D. Genetic polymorphisms of interleukin 8 and risk of ulcerative colitis in the Chinese population. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;405(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rafrafi A, Chahed B, Kaabachi S, Kaabachi W, Maalmi H, Hamzaoui K, Sassi FH. Association of IL-8 gene polymorphisms with non small cell lung cancer in Tunisia: a case control study. Hum Immunol. 2013;74(10):1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull J, Thomson A, Kwiatkowski D. Association of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis with the interleukin 8 gene region in UK families. Thorax. 2000;55(12):1023–1027. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chouchane L, Sfar I, Bousaffara R, El Kamel A, Sfar M, Ismail A. A repeat polymorphism in interleukin–4 gene is highly associated with specific clinical phenotypes of asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;120(1):50–55. doi: 10.1159/000024219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroegel C. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines: 15 years of application. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5(3):239–249. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamzaoui K, Bouali E, Ghorbel I, Khanfir M, Houman H, Hamzaoui A. Expression of Th-17 and RORgammat mRNA in Behçet’s disease. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(4):CR227–CR234. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MWer S, Dykes D, Polesky H. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, Lin Y, Ding C. The role of neutrophils and interleukin-8 in pathogenesis of asthma. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2001;24(4):225–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada A, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. The biological, biochemical, and molecular profile of leukocyte chemotactic and activating cytokine, interleukin-8. Cytokines. 1997;2:277–317. doi: 10.1016/S1874-5687(97)80028-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y-C, Zhou Q-T, Yao W-Z. Sputum interleukin-17 is increased and associated with airway neutrophilia in patients with severe asthma. Chin Med J. 2005;118(11):953–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindén A. Role of interleukin-17 and the neutrophil in asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2001;126(3):179–184. doi: 10.1159/000049511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman M, Yang J, Shan LY, Unruh H, Yang X, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17R activation of human airway smooth muscle cells induces CXCL-8 production via a transcriptional-dependent mechanism. Clin Immunol. 2005;115(3):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian M, Zhao D, Wen G, Shi S, Chen R. Association between interleukin-8 gene-251 locus polymorphism and respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis and post-bronchiolitis wheezing in infants. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2007;45(11):856–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Y-W, Sun Q-Q, Feng J-Q, Hu A-M, Liu H-L, Wang Q. Influence of interleukin gene polymorphisms on development of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(10):5931–5941. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D, Li J, Wang L, Zhang Q. Association between IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10 polymorphisms and risk of acute pancreatitis. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:6635–6641. doi: 10.4238/2015.June.18.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taguchi A, Ohmiya N, Shirai K, Mabuchi N, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Niwa Y, Goto H. Interleukin-8 promoter polymorphism increases the risk of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer in Japan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(11):2487–2493. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atalay A, Arıkan S, Ozturk O, Öncü M, Tasli ML, Duygulu S, Atalay EO. The IL-8 gene polymorphisms in behçet’s disease observed in Denizli Province of Turkey. Immunol Invest. 2016;45(4):298–311. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2016.1153652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matheson MC, Ellis JA, Raven J, Walters EH, Abramson MJ. Association of IL8, CXCR2 and TNF-α polymorphisms and airway disease. J Human Genet. 2006;51(3):196–203. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campa D, Hung RJ, Mates D, Zaridze D, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Rudnai P, Lissowska J, Fabiánová E, Bencko V, Foretova L. Lack of association between − 251 T > A polymorphism of IL8 and lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(10):2457–2458. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee W-P, Tai D-I, Lan K-H, Li AF-Y, Hsu H-C, Lin E-J, Lin Y-P, Sheu M-L, Li C-P, Chang F-Y. The − 251T allele of the interleukin-8 promoter is associated with increased risk of gastric carcinoma featuring diffuse-type histopathology in Chinese population. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(18):6431–6441. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hull J, Ackerman H, Isles K, Usen S, Pinder M, Thomson A, Kwiatkowski D. Unusual haplotypic structure of IL8, a susceptibility locus for a common respiratory virus. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(2):413–419. doi: 10.1086/321291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osada S, Yamamoto H, Nishihara T, Imagawa M. DNA binding specificity of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein transcription factor family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(7):3891–3896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohyauchi M, Imatani A, Yonechi M, Asano N, Miura A, Iijima K, Koike T, Sekine H, Ohara S, Shimosegawa T. The polymorphism interleukin 8–251 A/T influences the susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori related gastric diseases in the Japanese population. Gut. 2005;54(3):330–335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emonts M, Hazes MJ, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, van der Gaast-de CE, de Vogel L, Han HK, Wouters JM, Laman JD, Dolhain RJ. Polymorphisms in genes controlling inflammation and tissue repair in rheumatoid arthritis: a case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poli V. The role of C/EBP isoforms in the control of inflammatory and native immunity functions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(45):29279–29282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.