Abstract

The role of viral load in the outcome of patients requiring hospital admission due to influenza is not well established. We aim to assess if there is an association between the viral load and the outcome in hospitalized patients with a confirmed influenza virus infection. A retrospective observational study including all adult patients who were hospitalized in our center with a confirmed influenza virus infection from January to May 2016. Viral load was measured by real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) cycle threshold (Ct) value on upper respiratory tract samples. Its value was categorized into three groups (low Ct, ≤ 20; intermediate Ct, > 20–30; and high Ct, > 30). Two hundred thirty-nine patients were included. Influenza A/H1N1pdm09 was isolated in 207 cases (86.6%). The mean Ct value was 26.69 ± 5.81. The viral load was higher in the unvaccinated group when compared with the vaccinated patients (Ct 25.17 ± 5.55 vs. 27.58 ± 4.97, p = 0.004). Only 27 patients (11.29%) presented a high viral load. Patients with a high viral load more often showed abnormal findings on chest X-ray (p = 0.015) and lymphopenia (p = 0.097). By contrast, there were no differences between the three groups (according to viral load), in associated pneumonia, respiratory failure, need for mechanical ventilation, sepsis, or in-hospital mortality. Our findings suggest that in patients admitted to the hospital with confirmed influenza virus infection (mostly A/H1N1pdm09), a high viral load is associated with a higher presence of abnormal findings on chest X-ray but not with a significant worse prognosis. In these cases, standardized quantitative PCR could be useful.

Keywords: Influenza, Pneumonia, Lymphopenia, Viral load, Outcome, Mortality

Introduction

We recently reported the potential role of severe hematological abnormalities as prognostic markers in hospitalized patients with influenza virus infection [1]. However, the role of viral load in the clinical outcome and/or in the appearance of some severe hematological abnormalities was not evaluated.

Previous studies have hypothesized that viral load of some respiratory viruses correlate with disease severity [2], but this association is not clear in the case of influenza virus infection [3, 4]. On the contrary, other authors have found that high influenza viral load is associated with a longer duration of hospital stay in adults with viral acute respiratory illness [5]. On this basis, we decided to analyze the role of influenza viral load in the outcome of the patients included in the same cohort of our previous paper [1].

The aim of the present study was to assess if there is an association between viral load measured by real-time reverse-transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) cycle threshold (Ct) value on upper respiratory tract samples and the outcome in patients who were admitted to the hospital with a confirmed influenza virus infection.

Material and methods

Study population

This is a retrospective observational study including all adult patients with a diagnosis of influenza virus infection hospitalized from January to May 2016 in a 1300-bed tertiary teaching hospital in Madrid, Spain. The study protocol was approved by the University Hospital “12 de Octubre” Review Board.

Microbiological methods

A case was defined by a positive result of a rRT-PCR assay performed at the local laboratory on respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swabs (flocked swabs in UTM™ viral transport medium, Copan, Brescia, Italy)) from adult patients with respiratory symptoms suggestive of influenza. For the molecular diagnosis, RNA was extracted from 200 μl of the specimen using NucliSENS®easyMAG instrument (bioMérieux Diagnostics, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and eluted in 50 μl. Five microliters of the elution was used to perform each RT-PCR. The modular duplex rRT-PCR for influenza A/influenza B detection (Influenza A/B r-gene™, bioMérieux) was run in the LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche) [6]. This test has 45 cycles of amplification and a Ct > 40 is considered below the limit of detection of the technique according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

All samples testing positive for influenza A were sub-typed using a non-commercial rRT-PCR assay as previously described [7] to detect specific regions of subtypes H1 and H3 hemagglutinin from seasonal viruses. For the detection of influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 subtype, commercially available primers and probe (RealTime ready infA/H1N1 Detection set, Roche) [8] were used.

The real-time PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value represents the first PCR cycle in which the fluorescent signal for the target is greater than the minimal detection level [9, 10].

Study definitions

Respiratory failure was defined as the need for mechanical ventilation, either non-invasive positive pressure ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation, including those patients who had a clinical indication for ventilatory support but for some reason were finally not ventilated.

Sepsis, septic shock, and organ dysfunction were defined according to the terms proposed recently by the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock [11], including the SOFA score and the qSOFA score. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was defined according to the American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS [12, 13].

Poor outcome was defined as a composite endpoint in which at least one of the following criteria had to be fulfilled: (a) respiratory failure, (b) SOFA ≥ 2, or (c) death (related or not related to influenza infection).

Hematological abnormalities secondary to influenza virus infection were defined as cytopenias that were in the range of the HLH-04 updated criteria proposed by the Histiocyte Society [14] for the diagnosis of hematophagocytic syndrome (HPS) (hemoglobin ≤ 9 g/dl, platelets < 100,000/μl, neutrophils < 1000/μl). Since lymphopenia is not included in the HLH-04 criteria, we defined it as a total count less than 1000 lymphocytes/μl.

Statistical methods

A descriptive analysis of patients was initially performed according to Ct value (viral load). Descriptive analysis was performed using means (± SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Initially, the Ct value was categorized into three groups (low Ct, ≤ 20; intermediate Ct, > 20–30; and high Ct, > 30) and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to explore differences across these groups. Later, we compared patients who had a high viral load (Ct ≤ 20) with those who did not have a high viral load (Ct > 20). Student’s t test for independent samples was used to compare continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables with a non-normal distribution, and the Fisher exact test to compare proportions. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to establish the best viral load that determined the presence of the composite endpoint or respiratory failure, and corresponding sensitivity and specificity were reported. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was also calculated. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp and SAS/STAT 10.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results and discussion

We included 239 hospitalized patients with confirmed influenza virus infection. The mean Ct value was 26.69 ± 5.81. Twenty-seven patients (11.29%) had a low Ct, 138 cases (57.74%) had an intermediate Ct, and 74 patients (30.96%) had a high Ct. Two hundred seven cases were positive for influenza A (86.6%), all of them by the H1N1pdm09 subtype, while the other 32 cases were positive for influenza B. First of all, we want to point out that most of the previous published information of the influence of viral load of H1N1pdm09 subtype on the prognosis of patients is prior to the introduction of this strain in the vaccine [4, 15–17]. In fact, only Spencer’s work [18] includes patients after the modification of the vaccine, but focuses on factors associated with low Ct and not in the evolution or development of complications. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that analyzes the influence of influenza A H1N1pdm09 viral load on the prognosis of patients after the inclusion of the strain in the vaccine.

Clinical characteristics

Patient’s demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as management of the infection, are shown in Table 1. Ninety-six patients were previously vaccinated. Viral load was higher in the unvaccinated group when compared with that of the vaccinated patients (Ct 25.17 ± 5.55 vs. 27.58 ± 4.97, p = 0.004). Practically all of the patients were treated with oseltamivir (96.7%) in the early phase of the infection. As our work included a very homogeneous population, it is unlikely that the presence or absence of antiviral treatment has influenced the clinical course of the disease.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with influenza infection

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 239) | Ct value (viral load) | P valuea | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 20 (n = 27) | > 20–30 (n = 138) | > 30 (n = 74) | ||||

| Age (years) | 67.08 ± 16.09 | 70.11 ± 15.91 | 66.13 ± 16.56 | 67.72 ± 15.29 | 0.46 | 0.21 |

| Sex (male) | 142 (59.7%) | 18 (66.7%) | 78 (56.9%) | 46 (62.2%) | 0.55 | 0.41 |

| Charlson comorbidity index score | 2 (1–4) | 2 (0.25–3.75) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.58 | 0.33 |

| Previous comorbid conditions | ||||||

| Active smoker | 48 (20.1%) | 5 (18.5%) | 29 (21%) | 14 (18.9%) | 0.91 | 0.82 |

| Obesity | 43 (18%) | 6 (22.2%) | 24 (17.4%) | 13 (17.6%) | 0.83 | 0.59 |

| Asthma | 15 (6.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 10 (7.2%) | 4 (5.4%) | 0.73 | 1 |

| COPD | 51 (21.3%) | 5 (18.5%) | 33 (23.9%) | 13 (17.6%) | 0.52 | 0.7 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 68 (28.5%) | 6 (22.2%) | 38 (27.5%) | 24 (32.4%) | 0.56 | 0.44 |

| Immunosuppression (including steroids)* | 53 (22.2%) | 3 (11.1%) | 34 (24.6%) | 16 (21.6%) | 0.29 | 0.14 |

| Influenza vaccination (last year) | 96 (40.3%) | 10 (37%) | 50 (36.5%) | 36 (48.6%) | 0.21 | 0.71 |

| Influenza A H1N1pdm09 (vs influenza B) | 207 (86.6%) | 27 (100%) | 125 (90.6%) | 55 (74.3%) | < 0.001 | 0.031 |

| Duration of illness prior to confirming the infection (days) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–7) | 3 (2–4.75) | 3.5 (2–5) | 0.114 | 0.54 |

| Clinical findings at admission | ||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.62 ± 1.02 | 37.9 ± 0.9 | 37.58 ± 0.99 | 37.60 ± 1.11 | 0.39 | 0.17 |

| Dyspnea | 142 (59.4%) | 18 (66.7%) | 88 (63.8%) | 36 (48.6%) | 0.073 | 0.41 |

| Respiratory rate | 19.95 ± 7.97 | 23.83 ± 11.66 | 19.38 ± 7.41 | 20.26 ± 8.29 | 0.71 | 0.45 |

| SpO2 (%) | 91.28 ± 5.95 | 90.92 ± 4.72 | 91.47 ± 5.1 | 91.04 ± 5.13 | 0.59 | 0.52 |

| Bronchospasm | 102 (42.7%) | 9 (33.3%) | 54 (39.1%) | 39 (52.7%) | 0.095 | 0.29 |

| Chest X-ray abnormal findings | 113 (50.2%) | 20 (76.9%) | 61 (46.9%) | 32 (46.4%) | 0.015 | 0.004 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Oseltamivir | 231 (96.7%) | 27 (100%) | 134 (97.1%) | 70 (94.6%) | 0.37 | 0.6 |

| Empiric antibiotic therapy | 174 (72.8%) | 17 (63%) | 103 (74.6%) | 54 (73%) | 0.45 | 0.22 |

| Pathogen directed antibiotic therapy | 17 (7.1%) | 3 (11.1%) | 9 (6.5%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.69 | 0.41 |

| Treatment with steroids | 136 (56.9%) | 17 (63%) | 76 (55.1%) | 43 (58.1%) | 0.72 | 0.32 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) or as absolute value (percentage). *Immunosuppression was defined as the presence of any the following: active malignant neoplasia, autoimmune disease, solid organ transplantation, HIV infection, use of steroids or chemotherapy. Use of steroids was defined as (1) more than 20 mg/day of oral prednisone during 7 days or longer or (2) less than 20 mg/day during a minimum of 3 months. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. aAcross all Ct value groups. bBetween high viral load group (Ct ≤ 20) and other groups combined. Bold font means significant differences between variables

Laboratory tests

Very little is known about the potential influence of viral load of influenza virus on the development of cytopenias. In fact, the scarce existing information indicates that viral load of different respiratory viruses does not influence the white blood cell count in patients with an acute respiratory illness [5].

Laboratory parameters of our study are presented in Table 2. The mean Ct was 26.52 ± 6.45 in the group with at least one hematological abnormality vs. 26.73 ± 6.64 in the group without cytopenias (p = 0.81). Regarding laboratory parameters, we found that the only cell lines that seemed to be affected by the viral load are lymphocytes. Lymphopenia was present in 59.1% of patients upon admission, reaching up to 71.7% throughout hospital stay, with significant differences between the three groups according to the Ct value (p = 0.006 and p = 0.097). The mean Ct was 26.40 ± 6.15 in the group with lymphopenia vs. 27.49 ± 4.86 in the group without lymphopenia (p = 0.15). However, the ROC curve analysis did not show a Ct cut-off that adequately predicted the presence of lymphopenia (AUC, 0.55; 0.47–0.63, p = 0.19).

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters of patients with influenza infection

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 239) | Ct value (viral load) | P valuea | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 20 (n = 27) | > 20–30 (n = 138) | > 30 (n = 74) | ||||

| Baseline laboratory findings | ||||||

| Leukocytes (×103 cells/μl) | 8.1 (5.55–10.95) | 8.2 (5.55–11.2) | 8.1 (5.55–10.9) | 8.2 (5.55–11.2) | 0.86 | 0.63 |

| Neutrophils (×103 cells/μl) | 6.1 (3.85–9.15) | 6.2 (3.3–9.8) | 6 (3.7–9.15) | 6.3 (4.15–9) | 0.93 | 0.79 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 76.71 ± 13.69 | 82.61 ± 9.9 | 75.82 ± 13.24 | 76.42 ± 15.6 | 0.044 | 0.024 |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μl) | 800 (500–1200) | 500 (400–800) | 900 (600–1300) | 700 (450–1200) | 0.025 | 0.0001 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 11 (6.02–18) | 7.8 (4.3–16) | 11.8 (6.32–20.45) | 11 (5.5–16.8) | 0.11 | 0.071 |

| Platelets (×103/μl) | 187 (146–245) | 159 (118–269) | 204 (155–246.5) | 183 (133–231) | 0.28 | 0.48 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.06 ± 2.13 | 13.41 ± 1.41 | 12.92 ± 2.33 | 13.22 ± 2.02 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| LDH (U/l) | 274.5 (223.7–347.7) | 324 (223.7–392) | 278 (227–364) | 261 (221–319) | 0.15 | 0.23 |

| Hypertransaminasemia | 48 (20.1%) | 7 (25.9%) | 35 (25.4%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.008 | 0.42 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 5.31 (2.44–11.55) | 7.49 (3.72–11.87) | 5.36 (2.45–11.94) | 4.61 (2.13–9.95) | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| Peak laboratory values | ||||||

| LDH (U/l) | 292 (247.5–394.5) | 329 (248–537) | 296 (253–386) | 276 (240–366) | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| LDH > 225¶ | 196 (83.8%) | 22 (81.5%) | 114 (85.1%) | 60 (82.2%) | 0.81 | 0.78 |

| AST (mg/dl) | 30 (23–51) | 51 (22–79) | 30 (23.75–44.2) | 27 (22–44) | 0.29 | 0.064 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 8 (4–15) | 10 (4.75–13.5) | 8 (4–15.5) | 8 (3–15) | 0.77 | 0.34 |

| Nadir blood cell count | ||||||

| Leukocytes (×103 cells/μl) | 5.8 (4.15–8.1) | 5.7 (3.9–8.5) | 5.8 (4.12–7.7) | 6.35 (4.27–8.45) | 0.73 | 0.9 |

| Neutrophils (×103 cells/μl) | 3.7 (2.4–5.65) | 3.9 (2.2–6.2) | 3.4 (2.4–5.27) | 4.45 (2.8–6.32) | 0.61 | 0.8 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 64.09 ± 16.39 | 68.5 ± 15.23 | 62.14 ± 16.47 | 66.07 ± 16.29 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Lymphocytes (cells/μl) | 700 (400–1000) | 500 (300–700) | 700 (500–1000) | 600 (400–1100) | 0.09 | 0.032 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 9.4 (5.1–16.5) | 7.15 (4.07–16) | 10.2 (5.6–16.3) | 9.2 (4.75–16.8) | 0.27 | 0.13 |

| Platelets (×103/μl) | 176 (119–227.5) | 134 (99–235) | 178 (135.5–228) | 172 (109–221.2) | 0.3 | 0.24 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.96 ± 2.35 | 11.89 ± 2.06 | 11.92 ± 2.54 | 12.08 ± 2.11 | 0.94 | 0.85 |

| Hematological abnormalities | ||||||

| < 1000 neutrophils/μl* | 14 (5.9%) | 2 (7.4%) | 7 (5.1%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.82 | 0.66 |

| < 100,000 platelets/μl* | 36 (15.1%) | 7 (25.9%) | 16 (11.6%) | 13 (17.6%) | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Hemoglobin < 9 g/dl* | 25 (10.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 17 (12.3%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.45 | 1 |

| < 1000 lymphocytes/μl | 170 (71.7%) | 24 (88.9%) | 93 (68.4%) | 53 (71.6%) | 0.097 | 0.035 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) or as absolute value (percentage). NA not available. ¶Upper limit of LDH in the local laboratory is 225 mg/dl. *According to the HLH-04 criteria. aAcross all Ct value groups. bBetween high viral load group (Ct ≤ 20) and other groups combined. Bold font means significant differences between variables

Clinical outcome

As shown in Table 3, we observed that pulmonary radiological findings are more frequently found in patients with higher viral loads as previously described by other authors [17, 19, 20]. Twenty-eight patients (11.7%) developed pneumonia in the course of admission (p = 0.45 between groups). Eight patients with pneumonia were vaccinated (28.5%) vs. 41.7% in the group without pneumonia (p = 0.29).

Table 3.

Outcome of patients with influenza infection according viral load

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 239) | Ct value (viral load) | P valuea | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 20 (n = 27) | > 20–30 (n = 138) | > 30 (n = 74) | ||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 7 (5–12) | 9 (6–13) | 7 (5–11) | 8 (5–12.25) | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| ICU admission | 13 (5.4%) | 2 (7.4%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.34 | 0.64 |

| Pneumonia | 28 (11.7%) | 5 (18.5%) | 16 (11.6%) | 7 (9.5%) | 0.45 | 0.33 |

| Respiratory failure | 19 (7.9%) | 3 (11.1%) | 9 (6.5%) | 7 (9.5%) | 0.61 | 0.45 |

| ARDS | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0.38 | 1 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 9 (3.8%) | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 8 (3.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 4 (2.9%) | 3 (4.1%) | 0.9 | 1 |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (days) | 15.5 (8–28.5) | 22.5 (15–30) | 8 (4–18) | 16 (10–19) | 0.43 | 0.4 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 10 (4.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | 4 (2.9%) | 4 (5.4%) | 0.46 | 0.31 |

| Septic shock | 13 (5.4%) | 3 (11.1%) | 4 (2.9%) | 6 (8.1%) | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| SOFA score at ICU admission | 1 (0–3.75) | 3 (1.5–7.5) | 0 (0–3) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| SOFA ≥ 2 | 30 (15.1%) | 4 (19%) | 18 (15.7%) | 8 (12.7%) | 0.75 | 0.53 |

| qSOFA score | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.19 | 0.98 |

| qSOFA ≥ 1 | 58 (39.5%) | 5 (35.7%) | 29 (34.9%) | 24 (48%) | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Overall in-hospital mortality | 12 (5.2%) | 2 (7.7%) | 6 (4.5%) | 4 (5.5%) | 0.79 | 0.63 |

| Related mortality | 10 (4.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (4.1%) | 0.66 | 0.31 |

| Poor outcome (composite endpoint) | 42 (21.4%) | 5 (25%) | 26 (22.8%) | 11 (17.7%) | 0.67 | 0.77 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) or as absolute value (percentage). ICU intensive care unit, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome. aAcross all Ct value groups. bBetween high viral load group (Ct ≤ 20) and other groups combined

Respiratory failure was present in 7.9% of patients. We observed a slightly higher percentage of this item in those with the higher viral load without reaching statistical significance.

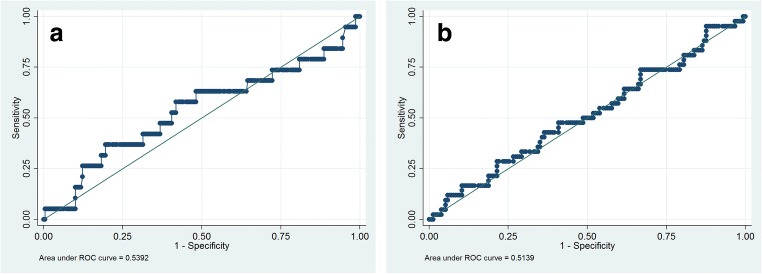

Poor outcome was present in 21.4% of patients with no differences between groups according to the Ct value (p = 0.67). The mean Ct was 26.58 ± 6.06 in the group with poor outcome vs. 26.81 ± 5.81 in the good prognosis group (p = 0.82). We also analyzed the association between the viral load and the need for ICU admission, without finding significant differences between groups. To the extent of our knowledge, a high viral load has not been previously analyzed as a predisposing factor for septic shock, use of vasoactive drugs, or SOFA score ≥ 2. We did not find differences in these regards, although we observed a trend to a more frequent presence of each of these items in patients with higher viral loads, as well as with mortality and the composite endpoint. We analyzed with ROC curves if the viral load had any influence on the development of ventilatory failure or the composite endpoint, without finding statistically significant relationships (Fig. 1). Overall in-hospital mortality was 5.2% and influenza-related mortality was 4.6%, without differences between groups (p = 0.63).

Fig. 1.

Respiratory failure and poor outcome according to Ct value. a Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using the value of Ct for discriminating respiratory failure (AUC = 0.53; 0.38–0.69, p = 0.59). b ROC curve analysis using the value of Ct for discriminating poor outcome (defined as a composite endpoint in which at least one of the following criteria had to be fulfilled: (a) respiratory failure, (b) SOFA ≥ 2, or (c) death (related or not related to influenza infection) (AUC = 0.51; 0.41–0.61, p = 0.82)

As shown in Table 4, there were no significant differences in the length of hospitalization according to viral load. Likewise, we did observe a slightly longer duration of admission in the subgroup of patients with pneumonia or ventilatory failure and higher viral loads. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one previous published study in patients with influenza infection that has analyzed the duration of hospitalization based on viral load [5]. However, this study was developed prior to the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 and none of the patients were treated with neuraminidase inhibitors.

Table 4.

Length of hospitalization (in days) according influenza viral load

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 239) | Ct value (viral load) | P valuea | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 20 (n = 27) | > 20–30 (n = 138) | > 30 (n = 74) | ||||

| All cases | 7 (5–12) | 9 (6–13) | 7 (5–11) | 8 (5–12.25) | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Pneumonia | 9 (5.25–14.75) | 13 (9–38.5) | 8 (4–10.75) | 9 (6–26) | 0.12 | 0.098 |

| Respiratory failure | 15.5 (8.5–51.5) | 45 (15-NA) | 13 (7–39.5) | 26 (14–53) | 0.447 | 0.26 |

| Poor outcome | 13 (6.75–33.25) | 37 (12.5–53.5) | 8 (5–17.5) | 14 (11–32) | 0.223 | 0.091 |

Results are expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR). aAcross all Ct value groups. bBetween high viral load group (Ct ≤ 20) and other groups combined

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that all patients included were hospitalized, which obviously correspond to greater disease severity, and it is possible that the difference in viral load is less striking in this group than if we had compared it with patients who did not require hospital admission. However, previous reports have described that there is no difference between viral loads of admitted patients compared with those in the ambulatory setting [3].

Another potential limitation of the study is that the commercially available diagnostic methods for the detection of influenza virus are qualitative techniques that do not allow the performance of a viral load in a strict sense. However, the Ct value is routinely used in virology laboratories as a semi-quantitative measure of the amount of virus present in samples as has been shown in previous studies [21–24]. Our data would support the use of quantitative PCR for the management of hospitalized patients with influenza virus infection in order to discriminate the presence of abnormal findings on chest X-ray or lymphopenia. However, the currently available viral load assays present several technical problems, including the lack of an international standard, the lack of consensus on specimen types, and the influence of the timing of specimen collection in viral load results [25]. In our opinion, it would be useful to have a standardized quantitative PCR as a diagnostic tool to evaluate these hospitalized patients.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that in hospitalized patients with influenza virus infection (mostly A/H1N1pdm09) receiving oseltamivir therapy, a high viral load is associated with some minor radiological changes but not with a significantly worse prognosis.

Author contributions

Antonio Lalueza, Dolores Folgueira, Carmen Díaz-Pedroche, and Carlos Lumbreras designed the study. Antonio Lalueza, Dolores Folgueira, and Irene Muñoz-Gallego screened the patients. Hernando Trujillo, Jaime Laureiro, Pilar Hernández-Jiménez, Noelia Moral-Jiménez, Estibaliz Arrieta, Marta Torres, Cristina Castillo, Blanca Ayuso, Coral Arévalo-Cañas, Carmen Díaz-Pedroche, and Olaya Madrid did acquisition of data. Antonio Lalueza and Hernando Trujillo created the first draft of the article. Antonio Lalueza, Dolores Folgueira, Carmen Díaz-Pedroche, and Carlos Lumbreras participated in the data interpretation and edited the article. Antonio Lalueza and Carlos Lumbreras wrote the final draft of the article and made all the changes suggested by the coauthors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the University Hospital “12 de Octubre” Review Board.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lalueza A, Trujillo H, Laureiro J, Ayuso B, Hernandez-Jimenez P, Castillo C, et al. Impact of severe hematological abnormalities in the outcome of hospitalized patients with influenza virus infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(10):1827–1837. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2998-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bont L. Why is RSV different from other viruses? J Med Virol. 2013;85(5):933–934. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granados A, Peci A, McGeer A, Gubbay JB. Influenza and rhinovirus viral load and disease severity in upper respiratory tract infections. J Clin Virol. 2017;86:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noh JY, Song JY, Hwang SY, Choi WS, Heo JY, Cheong HJ, et al. Viral load dynamics in adult patients with A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(4):753–758. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark TW, Ewings S, Medina MJ, Batham S, Curran MD, Parmar S, et al. Viral load is strongly associated with length of stay in adults hospitalised with viral acute respiratory illness. J Inf Secur. 2016;73(6):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillet S, Lardeux M, Dina J, Grattard F, Verhoeven P, Le Goff J, et al. Comparative evaluation of six commercialized multiplex PCR kits for the diagnosis of respiratory infections. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suwannakarn K, Payungporn S, Chieochansin T, Samransamruajkit R, Amonsin A, Songserm T, et al. Typing (A/B) and subtyping (H1/H3/H5) of influenza A viruses by multiplex real-time RT-PCR assays. J Virol Methods. 2008;152(1–2):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tham N, Hang V, Khanh TH, Viet do C, Hien TT, Farrar J, et al. Comparison of the Roche RealTime ready Influenza A/H1N1 Detection Set with CDC A/H1N1pdm09 RT-PCR on samples from three hospitals in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginzinger DG. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(6):503–512. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(02)00806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steininger C, Kundi M, Aberle SW, Aberle JH, Popow-Kraupp T. Effectiveness of reverse transcription-PCR, virus isolation, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of influenza A virus infection in different age groups. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(6):2051–2056. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2051-2056.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estenssoro E, Reina R, Canales HS, Saenz MG, Gonzalez FE, Aprea MM, et al. The distinct clinical profile of chronically critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R89. doi: 10.1186/cc4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duchamp MB, Casalegno JS, Gillet Y, Frobert E, Bernard E, Escuret V, et al. Pandemic A(H1N1)2009 influenza virus detection by real time RT-PCR: is viral quantification useful? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(4):317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu UI, Wang JT, Chen YC, Chang SC. Severity of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection may not be directly correlated with initial viral load in upper respiratory tract. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6(5):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu PX, Deng YY, Yang GL, Liu WL, Liu YX, Huang H, et al. Relationship between respiratory viral load and lung lesion severity: a study in 24 cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza A pneumonia. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(4):377–383. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.08.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer S, Chung J, Thompson M, Piedra PA, Jewell A, Avadhanula V, et al. Factors associated with real-time RT-PCR cycle threshold values among medically attended influenza episodes. J Med Virol. 2016;88(4):719–723. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, Schmitz AM, Benoit SR, Louie J, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April-June 2009. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(20):1935–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To KK, Hung IF, Li IW, Lee KL, Koo CK, Yan WW, et al. Delayed clearance of viral load and marked cytokine activation in severe cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):850–859. doi: 10.1086/650581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huijskens EG, Biesmans RC, Buiting AG, Obihara CC, Rossen JW. Diagnostic value of respiratory virus detection in symptomatic children using real-time PCR. Virol J. 2012;9:276. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, Assiri A, Alhakeem RF, Albarrak A, et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(10):1590–1594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva PE, Figueiredo CA, Luchs A, de Paiva TM, Pinho MAB, Paulino RS, et al. Human bocavirus in hospitalized children under 5 years with acute respiratory infection, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2010. Arch Virol. 2018;163(5):1325–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorburn F, Bennett S, Modha S, Murdoch D, Gunson R, Murcia PR. The use of next generation sequencing in the diagnosis and typing of respiratory infections. J Clin Virol. 2015;69:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.06.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlton CL, Babady E, Ginocchio CC, Hatchette TF, Jerris RC, Li Y, et al. (2019) Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: viruses causing acute respiratory tract infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 32(1). 10.1128/CMR.00042-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]