Abstract

The proteins of trans-acyltransferase modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) self-organize into assembly lines, enabling the multienzyme biosynthesis of complex organic molecules. Docking domains comprised of ~25 residues at the C- and N-termini of these polypeptides (CDDs and NDDs) help drive this association through the formation of four-helix bundles. Molecular connectors like these are desired in synthetic contexts, such as artificial biocatalytic systems and biomaterials, to orthogonally join proteins. Here, the ability of six CDD/NDD pairs to link non-PKS proteins is examined using green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants. As observed through size-exclusion chromatography and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), matched but not mismatched pairs of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 fusion proteins associate with low micromolar affinities.

Keywords: docking domain, four-helix bundle, orthogonal connectors, polyketide synthase, fluorescent proteins, FRET

Graphical Abstract

Engineering macromolecular complexes that assemble into specific structures has been a long-standing goal in materials science, chemical engineering, and synthetic biology.1 These assemblies could facilitate such processes as the synthesis of medicines, the delivery of drugs, and the transport of energy. To help engineer these complexes, researchers have harnessed modular connectors such as oligonucleotides,2–4 metal-binding domains,5–7 and leucine zippers.8,9 However, these connectors each have their limitations: connecting proteins with oligonucleotides can be cumbersome, metalbinding domains have limited orthogonality, and leucine zippers require the interaction of long α-helices that can geometrically constrain the bound domains.

A promising yet largely unexplored class of connectors are the recently discovered four-helix bundle docking domains that commonly join polypeptides within the trans-acyltransferase modular polyketide synthases (trans-AT PKSs)(Figure 1).10–13 The enzymes that reside in these polypeptides mediate the synthesis of polyketide natural products.14–17 For groups of these enzymes known as modules (the calyculin assembly line contains thirty-three),18 to correctly elongate growing intermediates, the polypeptides of the assembly line need to be precisely ordered.

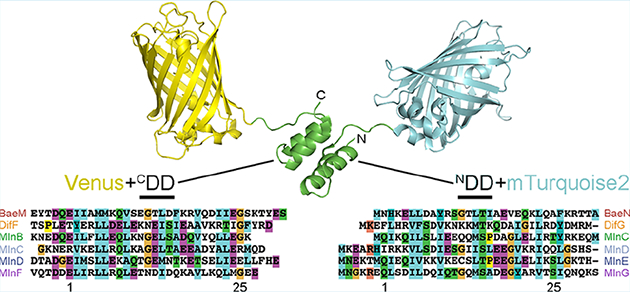

Figure 1.

Co-opting docking domains from biosynthetic assembly lines. (A) A comparison of enzymatic assembly line docking domains (PDB IDs 4MYY, 2N5D) shows that, while cis-AT assembly line docking domains (class 2 shown, but class 1 is also dimeric)22 are obligate dimers, trans-AT assembly line docking domains are not and could be useful in complexing proteins of various oligomerizaton states. KS, ketosynthase; AT, acyltransferase; ACP, acyl carrier protein. (B) C- and N-terminal docking domain (CDD and NDD) motifs were appended to the C-terminus of Venus and the N-terminus of mTurquoise2. The sequences of the six pairs used in this study from the bacillaene (Bae), difficidin (Dif), and macrolactin (Mln) assembly lines are displayed along with their numbering.13 BaeM/BaeN, bacillaene, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, CAG23959/CAG23960; DifF/DifG, difficidin, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, CAG23977/CAG23978; MlnB/MlnC/MlnD/MlnE/MlnF/MlnG, macrolactin, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, CAG23964/CAG23965/CAG23966/CAG23967/CAG23968/CAG23969.

While the polypeptides of the cis-AT PKSs,16,17,19 such as the erythromycin synthase, rely on homodimeric docking motifs C-terminal to the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain and N-terminal to the ketosynthase (KS) domain,20–22 the polypeptides of trans-AT PKSs are connected through split domains at various locations within the module. These domains can be enzymes such as ketoreductases (KRs) or dehydratases (DHs); however, the most common split domain is a four-helix bundle formed by two helices at the C-terminus of an upstream polypeptide and two helices at the N-terminus of a downstream polypeptide (the C- and N-terminal portions of the docking domain are referred to as CDD and NDD).13 CDD and NDD have been shown to interact in a pseudosymmetric manner with low micromolar affinity.12,13 While the docking domains of cis-AT and trans-AT PKSs both naturally operate in the context of homodimers, only those of trans-AT PKSs are functional as monomers and thus suited for (but not limited to) connecting monomeric proteins.

Cognate CDD/NDD pairs within Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 (a.k.a. Bacillus velezensis FZB42) help mediate the self-organization of the assembly lines that produce the polyketides bacillaene, difficidin, and macrolactin.14 In a previous study from our group, the association of portions of trans-AT PKS polypeptides containing cognate CDDs and NDDs was observed.13 Through swapping the CDD and NDD motifs new connections between PKS enzymes could be engineered. While these experiments indicated that CDD and NDD are portable between the polypeptides of trans-AT assembly lines, their ability to connect non-PKS proteins was not investigated.

Here, we report the use of B. amyloliquefaciens CDD/NDD pairs to orthogonally connect non-PKS proteins, demonstrating their ability to mediate the association of the monomeric green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants Venus and mTurquoise2.23,24 CDD and NDD motifs from the bacillaene, difficidin, and macrolactin assembly lines of B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42 appended to the termini of Venus and mTurquoise2 enabled orthogonal connectivities with low micromolar affinities. The association of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 cognates, visualized by size-exclusion chromatography and measured using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), demonstrates the utility of these docking domains in generating engineered complexes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Four helix-bundle docking domains connect polypeptides in each of the three trans-AT PKSs from B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42: once in the bacillaene assembly line (CDDBaeM/NDDBaeN for polypeptides BaeM/BaeN), once in the difficidin assembly line (CDDDifF/NDDDifG for polypeptides DifF/DifG), and four times in the macrolactin assembly line (CDDMlnB/NDDMlnC for polypeptides MlnB/MlnC, NDDMlnC/NDDMlnD for polypeptides MlnC/MlnD, NDDMlnD/NDDMlnE for polypeptides MlnD/MlnE, and NDDMlnF/NDDMlnG for polypeptides MlnF/MlnG)(Figure 1b). Each of these CDD and NDD motifs was fused to the yellow GFP variant Venus and the cyan GFP variant mTurquoise2, respectively.23,24 Venus+CDD fusion proteins were engineered by linking the Venus domain and CDD motif through a glycine, a serine, and 4–5 residues that naturally precede the CDD. Fusion NDD+Turquoise2 proteins were engineered by linking the NDD motif and mTurquoise2 domain with 5–6 residues naturally downstream of NDD. To minimize interference with CDD/NDD interactions, vector-encoded hexahistidine purification tags were positioned on the terminus opposite of the docking motif (N-terminal in Venus+CDD constructs and C-terminal in NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs). The 12 fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) from pET28b-derived plasmids and purified. Each construct showed the expected fluorescent properties, with the peak excitation and emission wavelengths at ~510 and ~530 nm for the Venus+CDD constructs and ~420 and ~480 nm for the NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs (Figure S1).

Orthogonal interactions were first observed between Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs by size-exclusion chromatography (Figures 2 and S2). When loaded individually onto a Superdex 200 column, Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs elute at 17–18 mL. However, when loaded together in equimolar amounts, matched pairs of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs primarily elute earlier, at ~15 mL, indicating the formation of a larger complex (with smaller peaks at 17–18 mL from residual, uncomplexed protein). The behavior of each Venus+CDD construct in the presence of each of the six NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs was also observed through a series of Coomassiestained SDS-PAGE gels. These gels indicated that for five of the six pairs tested, only cognate pairs of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 interact. For example, while Venus+CDDBaeM forms a complex with NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, it does not form a complex with any of the other NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs (Figure 2c). The other constructs show similar orthogonality, with the exception of Venus+CDDMlnB, which complexes weakly with the NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, and NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2 constructs (Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Size-exclusion chromatography docking assay. Data for Venus+CDDBaeM are shown here (data for all Venus+CDD constructs are reported in Figures S2 and S3). (A) Individually, the cognate constructs Venus+CDDBaeM and NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 elute at 17 mL. A coinjection results in a species that elutes at 15 mL. (B) A coinjection of the noncognate constructs Venus+CDDBaeM and NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2 does not generate an earlier-eluting species. (C) Venus+CDDBaeM paired with each of the NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs shows that only the coinjection with NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 results in complex formation (NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, red; NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, orange; NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2, green; NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, light blue; NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, navy; NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2, purple). Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels confirm that both the Venus+CDDBaeM and NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 constructs are present in the early eluting species (boxed in green). Legend for all SDS-PAGE gels: Lane 1, ladder (PageRuler Prestained Protein, Thermo Scientific); lanes 2–13, fractions 12–23; lane 14, Venus+CDD construct; lane 15, NDD+mTurquoise2 construct. Matched NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 and Venus+CDDBaeM appear in lanes 3–5 (corresponding to fractions 13–15), while mismatched constructs do not.

Measurements of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs enabled characterization of the concentration-dependent nature of their interactions. FRET is an energy transfer mechanism in which an excited donor fluorophore nonradiatively transfers energy to a nearby acceptor fluorophore and is commonly harnessed to detect bimolecular interactions by fusing interacting proteins or domains of interest to a complementary pair of donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins.25,26 Interactions that bring the donor and acceptor into close proximity enable FRET between the donor and acceptor, which results in increased acceptor and decreased donor fluorescence in response to donor excitation. The FRET efficiency E depends on the distance between the acceptor and donor, r

| (1) |

where R0 is the Förster radius, the distance between the acceptor and donor at which FRET efficiency is half its maximum value. In the experimental system described here, Venus and mTurquoise2 serve as both test proteins to assess the ability of CDD/NDD pairs to connect non-PKS proteins and as the acceptor/donor FRET pair to enable detection of CDD/NDD interactions. Because the Förster radius between Venus and mTurquoise2 (5.8 nm)27 is larger than the expected distance between chromophores upon docking domain-mediated connection, the FRET efficiency between CDD/NDD-complexed Venus and mTurquoise2 proteins is expected to be relatively high.

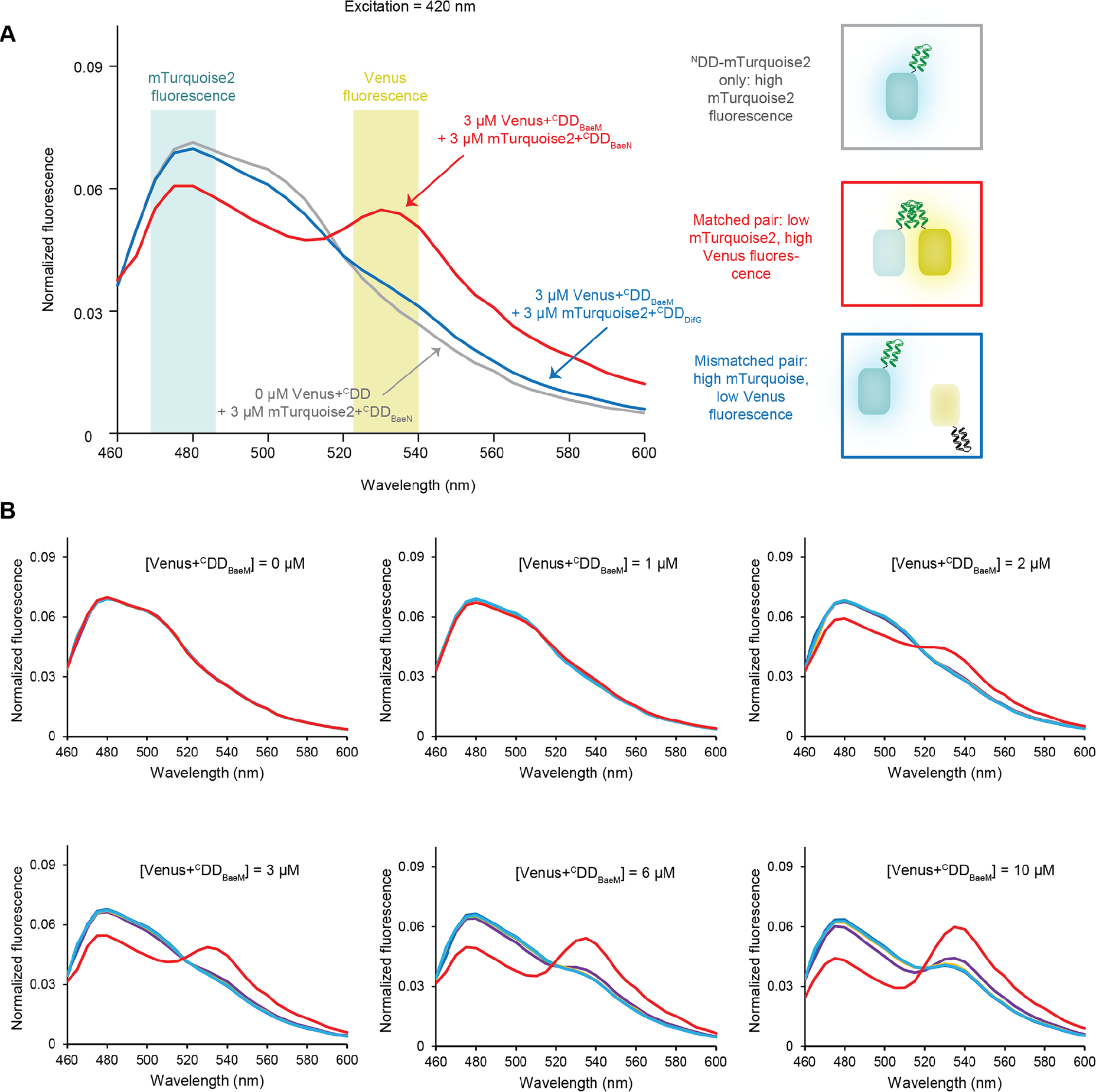

Consistent with the size-exclusion chromatography binding assays, FRET measurements indicated specific, orthogonal interactions between matched Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs (Figures 3 and S4–10). Normalized fluorescent spectra obtained from a solution containing 3 μM of Venus+CDDBaeM mixed with an equivalent amount of its cognate construct, NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, showed increased Venus fluorescence at ~530 nm, and decreased mTurquoise2 fluorescence at ~480 nm in response to excitation at 420 nm compared to spectra obtained from solutions containing NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 alone (processing and normalization are described in Figure S4). Conversely, fluorescence spectra obtained from combining noncognate constructs, such as Venus+CDDBaeM with NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, were similar to those obtained from solutions containing the NDD+mTurquoise2 construct alone (Figure 3a). The extent of fluorescence increase at ~530 nm and decrease at ~480 nm is dependent on the Venus+CDD concentration (Figures 3b and S5–10). For each Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 combination, containing 3 μM of the NDD+mTurquoise2 construct, the ~530 nm peak is evident at ~1 μM of the cognate Venus+CDD and grows to the same height as the ~480 nm peak at ~6 μM of the cognate Venus+CDD. Noncognate Venus+CDD constructs do not produce the ~530 nm peak unless present at significantly higher concentrations (due to either lower-affinity interactions between the noncognate pairs or weak fluorescence from excess Venus+CDD) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

FRET from complexes. (A) Emission spectra of an NDD+mTurquoise2 construct alone (gray), an equimolar matched Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 pair (red), and an equimolar unmatched Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 pair (blue) in response to direct excitation of NDD+mTurquoise2 at 420 nm. While excitation of an NDD+mTurquoise2 construct alone and in solution with an unmatched Venus+CDD construct produces a single peak at ~480 nm, excitation of a matched Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 pair produces a second emission peak at ~530 nm. (B) Emission spectra of increasing concentrations of Venus+CDDBaeM with 3 μM of each NDD+mTurquoise2 variant in response to 420 nm excitation. Increasing concentrations of Venus+CDDBaeM in the presence of its cognate, NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 (red), produces decreased donor and increased acceptor fluorescence. Increasing concentrations of Venus+CDDBaeM in the presence of noncognate NDD+mTurquoise2 proteins produce little effect until 10 μM, when acceptor fluorescence increases due to low-affinity interactions between mismatched CDD/NDD pairs or due to off-maximum excitation becoming too large to accurately subtract. NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, red; NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, orange; NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2, green; NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, light blue; NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, blue; NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2, purple. Because the spectra of the mismatched pairs are extremely similar, the NDDDifG+mTurquoise2 (orange), NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2 (green), and DDMlnE+mTurquoise2 (dark blue) spectra are mostly obscured.

Figure 4.

Emission spectra of 3 μM of each Venus+CDD with 3 μM of each mTurquoise+NDD. Thicker traces correspond to matched pairs. While matched pairs produce decreased donor fluorescence (480 nm) and increased acceptor fluorescence (530 nm), mismatched pairs do not. NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, red; NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, orange; NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2, green; NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, light blue; NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, blue; NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2, purple.

Plotting FRET efficiency as a function of Venus+CDD concentration further indicated the orthogonality of cognate Venus+CDD and NDD+Turquoise2 constructs. FRET efficiencies are most simply quantified as the ratio of the acceptor to either the donor or total fluorescence.25,26 However, accurate comparisons of such ratios generally require simple, often unimolecular, systems in which donor and acceptor concentrations remain constant. Bimolecular studies in which the concentrations of the donor or acceptor change have employed alternative methods.28–31 Here, a method25,29 was employed in which the FRET efficiency E at varying acceptor concentrations is quantified as

| (2) |

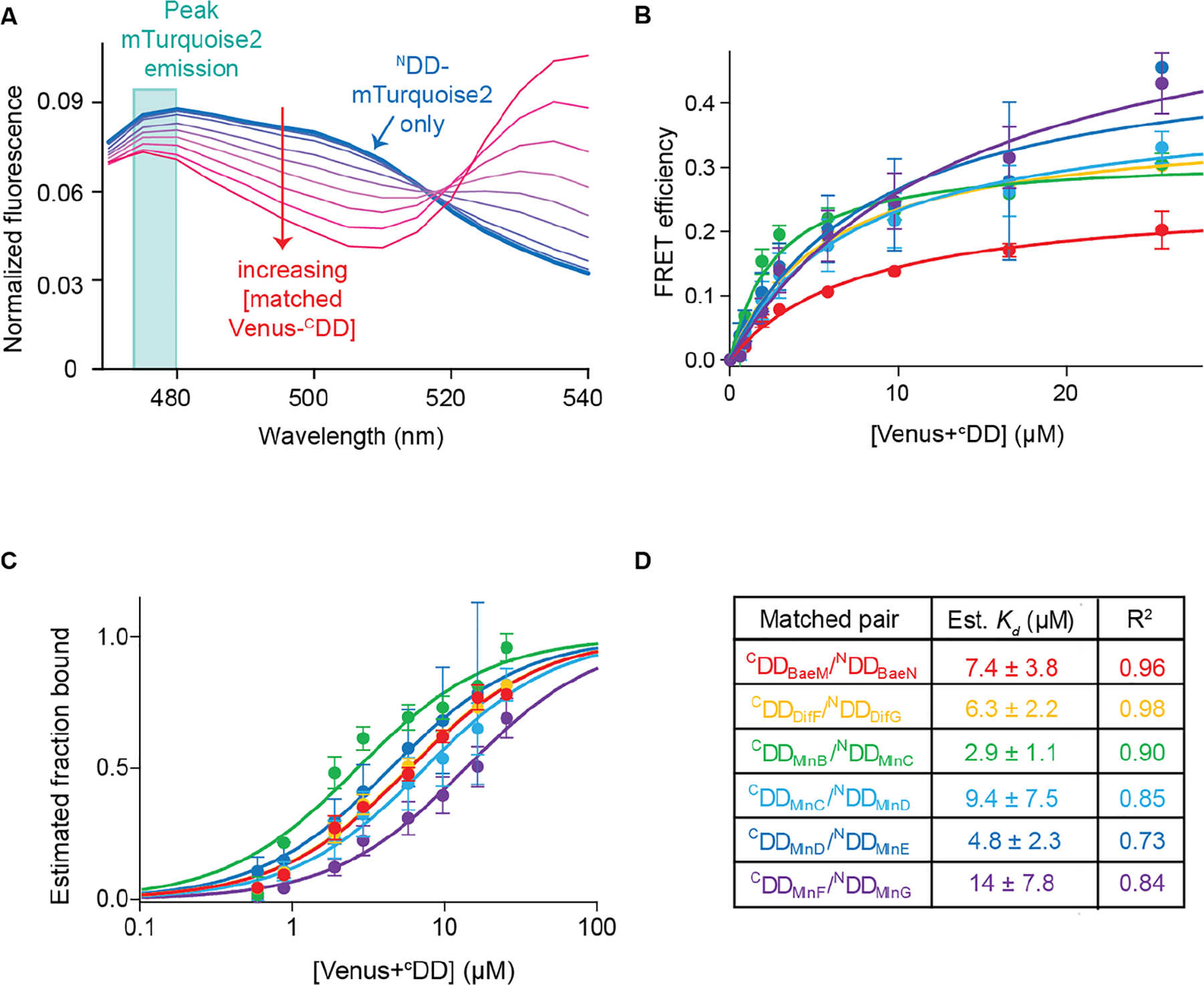

where the intensity of the donor emission is measured (at 480 nm) in the absence (Fd) and presence (Fda) of an acceptor (Figure 5a). Plotting E as a function of acceptor concentration for each of the six combinations of matched Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs shows that FRET efficiency increases with increasing acceptor concentration, and an analysis of all 36 combinations of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs reveals sharper increases for matched pairs compared to mismatched pairs (Figures 5b and S11).

Figure 5.

Estimating binding constants from the titration curves of matched pairs. (A) Plot showing normalized fluorescence curves obtained from titrating an increasing amount of Venus+CDD to its cognate NDD+mTurquoise2. The trace obtained from NDD+mTurquoise2 is shown as the thick blue line; traces obtained with increasing Venus+CDD concentration are shown as thinner purple to red lines. The turquoise box outlines the peak NDD+mTurquoise2 (donor) fluorescence at 475–480 nm. (B) Plots of the FRET efficiency E by Venus+CDD concentration for all matched pairs. Each color corresponds to a different matched pair: Venus+CDDBaeM/NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, red; Venus+CDDDifF/NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, orange; Venus+CDDMlnB/NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2, green; Venus+CDDMlnC/NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, light blue; Venus+CDDMlnD/NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, blue; Venus+CDDMlnF/NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2, purple. The data were fit well by a single-site binding curve function, as shown by the solid lines. Each point is the average of three replicates. Error bars correspond to standard deviations. (C) Plots of estimated fraction of NDD+mTurquoise2 bound at each Venus+CDD concentration using the data shown in panel B. (D) Estimated dissociation constant (Kd) values of matched pairs and R2 of fit to eq 3. Standard deviations are indicated.

Measurements of the FRET efficiency between Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs as a function of Venus+CDD concentration also enabled estimations of binding affinities. While the spectral overlap between Venus and mTurquoise2 precluded precise quantitation at concentrations of Venus+CDD much higher than NDD+mTurquoise2 required for the accurate determination of affinities (Figure S12),32 the obtained data were fit to binding isotherms to estimate Kd values25,29

| (3) |

Fitting the FRET efficiency versus Venus+CDD concentration data to this equation yielded Kd values in the low micromolar range with acceptable R2 values: Venus+CDDBaeM/NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, Kd = 7.4 ± 3.8 μM, R2 = 0.96; Venus+CDDDifF/NDDDifG+mTurquoise2, Kd = 6.3 ± 2.2 μM, R2 = 0.98; Venus+CDDMlnB/NDDMlnC+mTurquoise2, Kd = 2.9 ± 1.1 μM, R2 = 0.90; Venus+CDDMlnC/NDDMlnD+mTurquoise2, Kd = 9.4 ± 7.5 μM, R2 = 0.85; Venus+CDDMlnD/NDDMlnE+mTurquoise2, Kd = 4.8 ± 2.3 μM, R2 = 0.73; Venus+CDDMlnF/NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2, Kd = 14 ± 7.8 μM, R2 = 0.84 (Figure 5c and 5d). These values are similar to previously determined isothermal titration calorimetry measurements of the binding affinities of three of these cognate docking motifs in the context of their native polypeptides: CDDMlnC/NDDMlnD, Kd = 1.8 μM; CDDMlnD/NDDMlnE, Kd = 0.8 μM; CDDMlnF/NDDMlnG, Kd = 9.0 μM.13

Measurements were also made to determine whether salt concentration, pH, or small impurities from the Ni-NTA purifications had a significant impact on Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 interactions. FRET titrations were conducted at 37.5, 75, 150, and 300 mM NaCl for each combination of Venus+CDDBaeM and Venus+CDDMlnF with NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 and NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2 (Figure S13). These titrations indicated similar orthogonality of the matched Venus+CDD/NDD+mTurquoise2 pairs, with similar Kd values for the matched pairs (Venus+CDDBaeM/NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 and Venus+CDDMlnF/NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2) at each salt concentration (Figure S14). FRET titrations also showed that the Venus+CDDBaeM/NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2 and Venus+CDDMlnF/NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2 pairs demonstrate specific, orthogonal binding from pH 6.0 to 7.4 (Figure S15). Further purification of Ni-NTA-purified constructs by gel filtration chromatography did not result in significant changes in the measured FRET efficiencies (Figure S16).

Currently, the most utilized protein connectors are synthetic leucine-zipper coiled coils known as SYNZIP pairs.8,33,34 These can associate more tightly than the CDD’s and NDD’s of four helix bundle docking motifs, often with low nanomolar affinities. However, the binding orientations and oligomerization states are not known for many of these pairs, and orthogonality is a concern when several are used in the same system. The structure of the four helix docking domain complex has been characterized (PDB Codes 2N5D and 5D2E), and its CDD and NDD components have been naturally selected for orthogonality within organisms such as B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42.12,13 The smaller size of the four helix bundle docking motifs, approximately half that of SYNZIP motifs, also confers an advantage in many applications.

Engineered macromolecular complexes are desired in diverse synthetic biotechnologies; however, general strategies for their construction remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate the use of four-helix bundle docking domains from trans-AT assembly lines to connect synthetic proteins with low micromolar binding constants. They may be used to daisy-chain enzymes in a designed biosynthetic pathway or to connect arrays of light harvesting or metal templated proteins. The small size, portability, and orthogonality of these docking motifs augurs well for their broad utility as molecular connectors to generate desired synthetic biomolecular assemblies.

METHODS

Cloning and Protein Expression.

The DNA encoding each docking domain was amplified from the genomic DNA of B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42, and the genes encoding the GFP variants Venus and mTurquoise2 (F46L/F64L/S65G/V68L/S72A/D133G/M153T/V163A/S175G/T203Y and F64L/Y66W/S72A/N146F/H148D/M153T/V163A/S175G/A206K/H231L) were amplified from the YTK kit plasmids pYTK033 and pYTK057, respectively (Table S1). Amplicons were gel extracted and Gibson assembled into the pET28b expression vector (New England Biolabs) such that the hexahistidine tag is encoded opposite the docking domain. pET28b was digested with NdeI and XhoI to assemble Venus+CDD constructs and NcoI and XhoI to assemble NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs. The histidine-tagged fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (6 L of LB media) that were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 at 37 °C, induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and left overnight at 15 °C for NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs or 5 h at 37 °C for Venus+CDD constructs. Protein was purified from cell lysate using HisPur nickel-NTA resin (Thermo Scientific), flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C. Additional preparations of Venus+CDDBaeM, NDDBaeN+mTurquoise2, Venus+CDDMlnF, and NDDMlnG+mTurquoise2 were polished via gel filtration for salt- and pH-dependent FRET assays (GE Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column equilibrated in 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, and 10% (v/v) glycerol).

Size-Exclusion Chromatography Docking Assays.

Pairs of Venus+CDD and NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs were combined ~1:1 (75 μM for each protein) in a 1 mL volume and injected onto a Superdex 200 Increase gel filtration column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). Protein elution was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm, and fractions were collected every 0.5 mL after 9.5 mL had eluted. Individual domains were also run (75 μM in 1 mL). Fractions 12–23 from each run were analyzed with Coomassie-stained SDSPAGE gels loaded with 15 μL of each fraction.

FRET Measurements.

Fluorescence measurements were conducted in a solution containing 75 mM NaCl and 25 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.4) in all experiments, except where noted, and in a clear bottom 96-well plate. Fluorescence spectra were recorded between 460 and 600 nm (420 nm excitation, 5 nm intervals, ~25 °C). To obtain a titration curve, a Venus+CDD construct was successively added to solutions initially containing 3 μM of NDD+mTurquoise2 constructs and 220 μL total volume. Spectra taken at each concentration of the Venus+CDD construct were normalized by multiplying the ratio of current to starting volume to correct for dilution of the NDD+mTurquoise2 construct and subtracting a spectrum of a sample containing no NDD+Turquoise2 construct but an equivalent amount of the Venus+CDD construct in response to 420 nm excitation. To correct for signal decrease over time due to changes in solution refractive index due to increasing protein concentration, spectra were further normalized by dividing the fluorescence at each point by the sum of the fluorescence values taken between 470 and 540 nm. To estimate affinities, the normalized estimated FRET efficiencies were plotted as a function of Venus+CDD concentration in GraphPad Prism and fit to the standard single-site binding isotherm to yield Emax and Kd values.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM106112 to A.T.K.), the Welch Foundation (F-1712 to A.T.K.), the US Army Research Laboratory and the US Army Research Office (W911NF-1-51-0120 to A.D.E.), and an Arnold O. Beckman Postdoctoral Fellowship held by A.J.S.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00047.

Primer sequences, size-exclusion traces, SDS-PAGE analysis, data processing methods, fluorescence spectra, FRET efficiency plots, and titrations at differing pH and salt concentrations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Arai R (2018) Hierarchical design of artificial proteins and complexes toward synthetic structural biology. Biophys. Rev 10, 391–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Julin S, Nummelin S, Kostiainen MA, and Linko V (2018) DNA nanostructure-directed assembly of metal nanoparticle superlattices. J. Nanopart. Res 20, 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mohammed AM, Sulc P, Zenk J, and Schulman R (2017) Self-assembling DNA nanotubes to connect molecular landmarks. Nat. Nanotechnol 12, 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Praetorius F, and Dietz H (2017) Self-assembly of genetically encoded DNA-protein hybrid nanoscale shapes. Science 355, eaam5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bailey JB, Subramanian RH, Churchfield LA, and Tezcan FA (2016) Metal-Directed Design of Supramolecular Protein Assemblies. Methods Enzymol. 580, 223–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Priemel T, Degtyar E, Dean MN, and Harrington MJ (2017) Rapid self-assembly of complex biomolecular architectures during mussel byssus biofabrication. Nat. Commun 8, 14539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Alberstein R, Suzuki Y, Paesani F, and Tezcan FA (2018) Engineering the entropy-driven free-energy landscape of a dynamic nanoporous protein assembly. Nat. Chem 10, 732–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Reinke AW, Grant RA, and Keating AE (2010) A Synthetic Coiled-Coil Interactome Provides Heterospecific Modules for Molecular Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 6025–6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Jang Y, Choi WT, Heller WT, Ke Z, Wright ER, and Champion JA (2017) Engineering Globular Protein Vesicles through Tunable Self-Assembly of Recombinant Fusion Proteins. Small 13, 1700399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Piel J (2002) A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 14002–14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cheng YQ, Tang GL, and Shen B (2003) Type I polyketide synthase requiring a discrete acyltransferase for polyketide biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 3149–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Dorival J, Annaval T, Risser F, Collin S, Roblin P, Jacob C, Gruez A, Chagot B, and Weissman KJ (2016) Characterization of Intersubunit Communication in the Virginiamycin transAcyl Transferase Polyketide Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 4155–4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zeng J, Wagner DT, Zhang Z, Moretto L, Addison JD, and Keatinge-Clay AT (2016) Portability and Structure of the Four-Helix Bundle Docking Domains of trans-Acyltransferase Modular Polyketide Synthases. ACS Chem. Biol 11, 2466–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Piel J (2010) Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep 27, 996–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Helfrich EJ, and Piel J (2016) Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep 33, 231–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Keatinge-Clay AT (2012) The structures of type I polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep 29, 1050–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Keatinge-Clay AT (2017) The Uncommon Enzymology of Cis-Acyltransferase Assembly Lines. Chem. Rev 117, 5334–5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wakimoto T, Egami Y, Nakashima Y, Wakimoto Y, Mori T, Awakawa T, Ito T, Kenmoku H, Asakawa Y, Piel J, and Abe I (2014) Calyculin biogenesis from a pyrophosphate protoxin produced by a sponge symbiont. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 648–U193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Khosla C, Tang Y, Chen AY, Schnarr NA, and Cane DE (2007) Structure and mechanism of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Annu. Rev. Biochem 76, 195–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Weissman KJ (2006) The structural basis for docking in modular polyketide biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 7, 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gokhale RS, Tsuji SY, Cane DE, and Khosla C (1999) Dissecting and exploiting intermodular communication in polyketide synthases. Science 284, 482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Whicher JR, Smaga SS, Hansen DA, Brown WC, Gerwick WH, Sherman DH, and Smith JL (2013) Cyanobacterial polyketide synthase docking domains: a tool for engineering natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Biol 20, 1340–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, and Miyawaki A (2002) A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol 20, 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Goedhart J, van Weeren L, Hink MA, Vischer NOE, Jalink K, and Gadella TWJ (2010) Bright cyan fluorescent protein variants identified by fluorescence lifetime screening. Nat. Methods 7, 137–U174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miyawaki A (2011) Development of probes for cellular functions using fluorescent proteins and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Annu. Rev. Biochem 80, 357–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bajar BT, Wang ES, Zhang S, Lin MZ, and Chu J (2016) A Guide to Fluorescent Protein FRET Pairs. Sensors 16, 1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Erard M, Fredj A, Pasquier H, Beltolngar DB, Bousmah Y, Derrien V, Vincent P, and Merola F (2013) Minimum set of mutations needed to optimize cyan fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging. Mol. BioSyst 9, 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Song Y, Madahar V, and Liao J (2011) Development of FRET assay into quantitative and high-throughput screening technology platforms for protein-protein interactions. Ann. Biomed. Eng 39, 1224–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wei ZH, Chen H, Zhang C, and Ye BC (2014) FRET-based system for probing protein-protein interactions between sigmaR and RsrA from Streptomyces coelicolor in response to the redox environment. PLoS One 9, No. e92330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Palomba F, Genovese D, Petrizza L, Rampazzo E, Zaccheroni N, and Prodi L (2018) Mapping heterogeneous polarity in multicompartment nanoparticles. Sci. Rep 8, 17095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jiang L, Xiong Z, Song Y, Lu Y, Chen Y, Schultz JS, Li J, and Liao J (2019) Protein-Protein Affinity Determination by Quantitative FRET Quenching. Sci. Rep 9, 2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hulme EC, and Trevethick MA (2010) Ligand binding assays at equilibrium: validation and interpretation. Br. J. Pharmacol 161, 1219–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Grigoryan G, Reinke AW, and Keating AE (2009) Design of protein-interaction specificity gives selective bZIP-binding peptides. Nature 458, 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Thompson KE, Bashor CJ, Lim WA, and Keating AE (2012) SYNZIP protein interaction toolbox: in vitro and in vivo specifications of heterospecific coiled-coil interaction domains. ACS Synth. Biol 1, 118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.