Abstract

Body mass index (BMI) is an easily calculated indicator of a patient’s body mass including muscle mass and body fat percentage and is used to classify patients as underweight or obese. This study is to determine if BMI extremes are associated with increased 28-day mortality and hospital length of stay (LOS) in emergency department (ED) patients presenting with severe sepsis. We performed a retrospective chart review at an urban, level I trauma center of adults admitted with severe sepsis between 1/2005 and 10/2007, and collected socio-demographic variables, comorbidities, initial and most severe vital signs, laboratory values, and infection sources. The primary outcome variables were mortality and LOS. We performed bivariable analysis, logistic regression and restricted cubic spline regression to determine the association between BMI, mortality, and LOS. Amongst 1,191 severe sepsis patients (median age, 57 years; male, 54.7 %; median BMI, 25.1 kg/m2), 28-day mortality was 19.9 % (95 % CI 17.8–22.4) and 60-day mortality was 24.4 % (95 % CI 21.5–26.5). Obese and morbidly obese patients were younger, less severely ill, and more likely to have soft tissue infections. There was no difference in adjusted mortality for underweight patients compared to the normal weight comparator (OR 0.74; CI 0.42–1.39; p = 0.38). The obese and morbidly obese experienced decreased mortality risk, vs. normal BMI; however, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, this was no longer significant (OR 0.66; CI 0.42–1.03; p = 0.06). There was no significant difference in LOS across BMI groups. Neither LOS nor adjusted 28-day mortality was significantly increased or decreased in underweight or obese patients with severe sepsis. Morbidly obese patients may have decreased 28-day mortality, partially due to differences in initial presentation and source of infection. Larger, prospective studies are needed to validate these findings related to BMI extremes in patients with severe sepsis.

Keywords: Sepsis, Obesity, Body mass index, Organ dysfunction, Resuscitation

Introduction

Severe sepsis is responsible for at least 750,000 hospital admissions and over 215,000 deaths in the US each year [1]. Between 2004 and 2009, the incidence of severe sepsis increased by approximately 13 % annually, while the case-fatality rate decreased steadily [2]. Over $16.7 billion is spent within hospitals and on healthcare for patients with severe sepsis annually—an average of $22,000 per case [1]. The rising incidence, total mortality rate, and costs associated with severe sepsis continue to create major medical challenges. Understanding predisposing factors for worse outcomes in severe sepsis patients may aid accurate risk stratification and promote proper utilization of early, targeted treatment protocols [3].

Body mass index (BMI) is an easily calculated indicator of a patient’s body mass including muscle mass and body fat percentage and is used to classify patients as underweight or obese. The relationship between BMI and adverse patient outcomes is an increasingly important area of research across all areas of medicine due to the growing incidence of obesity in the United States and around the world [4]. Increased BMI has been shown to be a significant risk factor for chronic health conditions including diabetes, hypertension, degenerative joint disease and congestive heart failure. As the association between BMI and adverse chronic health conditions continues to be studied, further efforts are needed to elucidate the relationship between increased BMI and adverse outcomes in critical care situations, including severe sepsis and septic shock. Increased risks associated with extremely high and extremely low BMI exist for broadly defined populations and have generated U-shaped curves relating BMI and mortality [5]. This relationship, however, may not be observed in critically ill patients, where studies have yielded conflicting results [6–13]. Intensive Care Unit (ICU) data have demonstrated either: an increased risk in underweight, low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) patients [6, 7], an increased risk in obese, high BMI (>30 kg/m2) patients [8, 9], no significant difference associated with BMI [10–13], or a decreased risk in obese, high BMI patients [14].

The relationship between BMI and mortality has also been examined in specific diseases and during diverse procedures [2]; however, to date, only one study has examined this relationship in a cohort of patients with severe sepsis [14]. The primary goal of this study is to determine if BMI is associated with 28-day mortality in a patient population presenting to the emergency department (ED) with severe sepsis or septic shock. The secondary goal is to determine the impact of BMI on hospital length of stay (LOS). We hypothesized that extremes (high or low) of BMI would be significantly associated with increased 28-day mortality and LOS [15–22].

Materials and methods

Setting

This study took place at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania with a waiver of informed consent.

Patients

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients presenting to the ED and admitted to an urban, level I trauma center with severe sepsis between January 2005 and October 2007. Patient ED records were screened for the following inclusion criteria within the ED: evidence of a suspected infection, defined as the administration of antibiotics; the presence of two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria; and evidence of one or more signs of new onset organ dysfunction, in accordance with the 2001 International Consensus Conference definitions for severe sepsis [23]. Adult patients (≥18 years old) were included in the registry. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere by Mikkelsen et al. [24]. Review of patients’ medical records, discharge summaries, and assigned ICD-9 codes were used to confirm the diagnosis of severe sepsis in individual patients and validate the severe sepsis cohort.

Data collection and processing

Data were organized and recorded into a secure database; variables included: socio-demographics, comorbidities, initial and most severe vital signs, laboratory values, infection source, and mortality (in-hospital, 28-day, and 60-day). Triage vital signs, worst vital signs in the ED, and first laboratory results obtained after ED triage were utilized. Baseline vital signs and laboratory measurements were used to calculate the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, creatinine clearance (CrCl, calculated using Cockcroft-Gault equation,) and sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA) [25]. Height and weight were obtained from the admission record, procedure notes, or ICU flow sheets and used to calculate BMI (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). 28-day, 60-day, and 1-year mortality were obtained from the hospital record and confirmed via the social security death index (SSDI). The primary outcome was 28-day mortality, with 60-day and 1-year mortality as secondary outcomes. Patients without documented height, weight, or mortality information were excluded from the study. Chart abstractions were verified for accuracy by a separate member of the study team.

Statistical analysis

Due to non-normality, we compared baseline and clinical characteristics across categories of BMI using the Wilcoxon’s rank sum test or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables where appropriate and the Pearson’s Chi squared (χ 2) test for categorical variables.

We performed two analyses to determine the association between BMI and mortality. In the first analysis, BMI was divided into five quintiles according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) definitions: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2); normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2); overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2); obese (30.0–39.9 kg/m2); and morbidly (or extreme) obese (≥40.0 kg/m2) [26]. A bivariable analysis was used to determine the association between variables listed in Tables 1, 2 and 3 and mortality. We used logistic regression to measure the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) between BMI and mortality. Age and APACHE II score were included a priori into the base model. Variables that exhibited a p value of <0.20 on bivariable analysis were added to the base model one at time, and were retained in the final model if they altered the point estimate of the OR by >10 % [27].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes in the 1,191 subjects by BMI category

| Variables | Underweight (n = 102) | Normal (n = 480) | Overweight (n = 301) | Obese (n = 229) | Morbidly obese (n = 79) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.5 (43–69) | 57 (44–70) | 58 (47–70) | 56 (47–66) | 50.5 (42–63) | 0.04 |

| Male sex n (%) | 53 (52) | 271 (56.5) | 189 (62.8) | 112 (48.9) | 26 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| BMI | 16.8 (15.7–17.9) | 21.9 (20.4–23.4) | 27.3 (25.8–38.4) | 33.5 (31.7–35.9) | 46.9 (42.9–57.1) | <0.001 |

| Maximum temperature (°F) | 99.4 (97.8–101.7) | 100.7 (98.3–102.2) | 101.4 (99.8–102.6) | 101.4 (99.3–102.7) | 100 (98.5–102.2) | <0.001 |

| Maximum heart rate (beats per min) | 120 (107–139) | 118 (106–133) | 117 (102–128) | 121 (107–132) | 114 (98–129) | 0.12 |

| Maximum respiratory rate (per min) | 22 (20–30) | 24 (20–30) | 23 (20–28) | 24 (20–30) | 24 (20–28) | 0.23 |

| Minimum mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 65 (54–71) | 63 (54–76) | 67 (57–76) | 67 (56–80) | 71 (59–82) | 0.007 |

| Minimum systolic blood pressure | 93 (77–104) | 91 (80–111) | 99 (84–111) | 100 (84–117) | 106 (99–117) | <0.001 |

| White blood cells | 12.4 (6.5–18.1) | 13.1 (8.1–17.7) | 11.9 (7.1–17.1) | 10.9 (7–17.5) | 15 (11.4–19) | 0.002 |

| Platelets | 247 (156–379) | 225 (145–342) | 210 (123–291) | 222 (155–315) | 268 (207–335) | 0.003 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 1.2 (0.9–2.3) | 1.3 (0.9–2.1) | 1.5 (1–2.2) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 0.05 |

| Creatinine clearance | 42 (24–71) | 50 (28–81) | 63 (37–88) | 67 (42–107) | 94 (57–178) | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 111 (92–143) | 114 (94–155) | 120 (99–174) | 126 (99–174) | 132 (101–174) | 0.02 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.5 (0.3–1.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–2.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.7) | 0.6 (0.4–1.3) | 0.001 |

| PT | 14 (12.5–15.7) | 13.8 (12.7–16.1) | 14.3 (13–16.9) | 13.9 (12.7–15.9) | 14 (12.7–16.2) | 0.32 |

| PTT | 30.1 (26.1–38) | 29.3 (26–34.1) | 29.4 (25.4–34.6) | 27.7 (24.6–34.1) | 27.9 (25.5–31.6) | 0.07 |

| GCS | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 0.69 |

| Hematocrit | 33 (27–39) | 34 (29–39) | 34 (30–40) | 35 (29–40) | 38 (33–43) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 11.2 (9.3–13.1) | 11.4 (9.7–13.2) | 11.8 (10–13.3) | 12 (10–13.6) | 12.8 (11.3–14.4) | <0.001 |

| Lactate | 2.5 (1.8–4.1) | 2.8 (1.9–4.3) | 2.8 (2.1–4.1) | 2.9 (1.9–4.6) | 3.1 (2.5–4.9) | 0.12 |

| APACHE | 15 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) | 14 (10–19) | 15 (12–19) | 12 (9–19) | 0.21 |

| SOFA | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4.5) | 0.12 |

| EDGT n (%) | 32 (31.4) | 128 (26.7) | 65 (21.6) | 63 (27.5) | 15 (19.0) | 0.18 |

| Patient intubated n (%) | 17 (16.7) | 67 (14.0) | 49 (16.3) | 38 (16.6) | 15 (19.0) | 0.67 |

| Patient ever in MICU n (%) | 62 (60.8) | 263 (54.8) | 143 (47.5) | 120 (52.4) | 30 (38.0) | 0.03 |

| 28-day mortality n (%) | 24 (23.5) | 105 (21.9) | 60 (19.9) | 43 (18.8) | 5 (6.3) | 0.03 |

| 60-day mortality n (%) | 30 (29.4) | 131 (27.3) | 69 (22.9) | 48 (21.0) | 7 (8.9) | 0.01 |

| 1 year mortality n (%) | 41 (40.2) | 172 (35.8) | 96 (31.9) | 76 (33.2) | 11 (13.9) | 0.01 |

| Hospital LOS | 8 (4–14) | 6 (4–11) | 7 (4–13) | 6.5 (4–14) | 5 (3–9.5) | 0.18 |

BMI body mass index, PT ProThrombin time, PTT partial thromboplastin time, GCS glasgow coma scale, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment, MICU medical intensive care unit, LOS length of Stay

aData are presented as medians and interquartile ranges unless otherwise noted

Table 2.

Comorbidities in the 1,191 subjects by BMI category

| Variable n (%) | Underweight (n = 102) | Normal (n = 480) | Overweight (n = 301) | Obese (n = 229) | Morbidly obese (n = 79) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 14 (13.7) | 97 (20.2) | 79 (26.3) | 81 (35.4) | 23 (29.1) | <0.001 |

| HTN | 30 (39.4) | 171 (35.6) | 123 (40.9) | 107 (46.7) | 34 (43.0) | 0.004 |

| CAD | 8 (7.8) | 51 (10.6) | 36 (12.0) | 26 (11.4) | 6 (7.6) | 0.67 |

| CHF | 7 (6.9) | 48 (10.0) | 29 (9.6) | 27 (11.8) | 18 (22.8) | 0.004 |

| COPD | 4 (3.9) | 34 (7.1) | 16 (5.3) | 17 (7.4) | 7 (8.9) | 0.54 |

| Liver failure | 4 (3.9) | 32 (6.7) | 28 (9.3) | 19 (8.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.08 |

| HIV | 5 (4.9) | 26 (5.4) | 12 (4.0) | 10 (4.4) | 2 (2.5) | 0.80 |

| Oncology | 49 (48.0) | 164 (34.2) | 97 (32.2) | 72 (31.4) | 9 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Solid tumor with metastases | 15 (14.7) | 76 (15.8) | 38 (12.6) | 28 (12.2) | 3 (3.8) | 0.07 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (2.9) | 25 (5.2) | 9 (3.0) | 9 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0.19 |

| Leukemia | 5 (4.9) | 30 (6.3) | 30 (10) | 20 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| Chemotherapy in the past 4 weeks | 22 (21.6) | 105 (21.9) | 60 (20.0) | 44 (19.2) | 2 (2.5) | 0.003 |

| Immunosuppressed | 32 (31.4) | 172 (35.8) | 102 (33.9) | 67 (29.3) | 7 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Neutropenia | 4 (3.9) | 24 (5.0) | 9 (3.0) | 11 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.24 |

| End-stage renal disease | 7 (6.9) | 39 (8.1) | 21 (7.0) | 19 (8.3) | 6 (7.6) | 0.97 |

| Chronic renal Insufficiency | 14 (13.7) | 73 (15.2) | 53 (17.6) | 39 (17.0) | 10 (12.7) | 0.76 |

| Transplant | 11 (10.8) | 57 (11.9) | 43 (14.3) | 22 (9.6) | 2 (2.5) | 0.06 |

BMI body mass index, HTN hypertension, CAD coronary artery disease, CHF congestive heart failure, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV human immunodeficiency virus

Table 3.

Infection sources in the 1,191 subjects by BMI category

| Infection source n (%) | Underweight (n = 102) | Normal (n = 480) | Overweight (n = 301) | Obese (n = 229) | Morbidly obese (n = 79) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary bacteremia | 15 (14.7) | 94 (19.6) | 65 (21.6) | 30 (13.1) | 14 (17.7) | 0.14 |

| Central venous catheter | 10 (9.8) | 28 (5.8) | 16 (5.3) | 14 (6.1) | 3 (3.8) | 0.56 |

| Respiratory | 30 (29.4) | 152 (31.7) | 86 (28.6) | 65 (38.4) | 13 (16.5) | 0.15 |

| Urinary | 28 (27.5) | 109 (22.7) | 79 (26.3) | 42 (18.3) | 19 (24.1) | 0.31 |

| Surgical site | 1 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 9 (3.0) | 9 (3.9) | 3 (3.8) | 0.08 |

| Soft tissue | 7 (6.9) | 37 (7.7) | 23 (7.6) | 38 (16.6) | 19 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 14 (13.7) | 68 (14.2) | 44 (14.6) | 35 (15.3) | 16 (20.3) | 0.57 |

| Central nervous system | 2 (2.0) | 10 (2.1) | 6 (2.0) | 6 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0.97 |

BMI body mass index

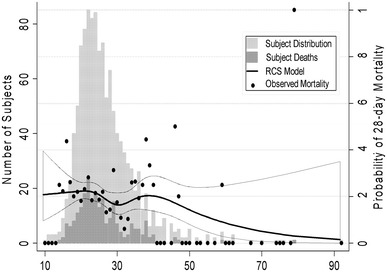

In the second analysis, we used a five-knot restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression model to plot the relationship between BMI as a continuous variable and mortality. Each knot represented one of the five BMI categories. The advantage of the RCS model is that it allows a nonlinear relationship in the fitted regression line [28].

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 software (Stata Datacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline characteristics

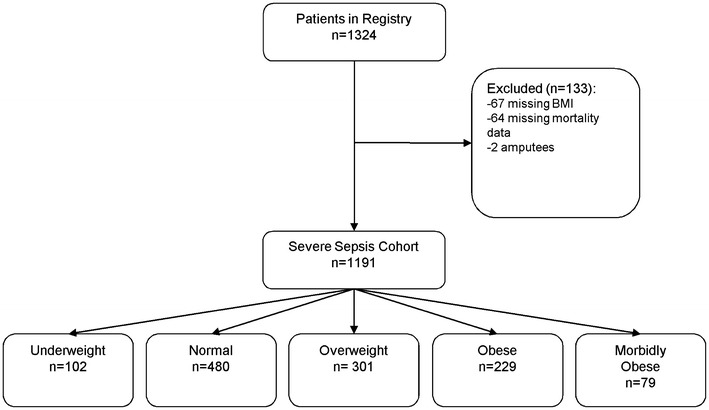

The cohort included 1,324 severe sepsis subjects between 2005 and 2007, 133 patients were excluded secondary to missing or unreliable BMI and mortality data, with a final cohort of 1,191 adult patients with severe sepsis (Fig. 1). The cohort was 54.7 % male, 53.6 % African American, with a median age of 57 years (IQR 45–69,) ranging from 18 to 102 years (Appendix 1) and median BMI of 25.1 kg/m2 (IQR 21.4–30.3). Overall cohort 28-day mortality was 19.9 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 17.8–22.4) and 60-day mortality was 24.4 % (95 % CI 21.5–26.5).

Fig. 1.

Enrollment and outcomes (BMI categories) for severe sepsis cohort

Characteristics of subjects by BMI category

Baseline and clinical characteristics across BMI categories are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3. There were significant differences across the BMI categories in both comorbidities and baseline clinical characteristics. The overweight, obese, and morbidly obese groups were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure, and less likely to have a cancer or be immunosuppressed (Table 1). Sources of infection also differed significantly across the groups. Obese and morbidly obese populations were more likely to have soft tissue infections as the cause of severe sepsis compared to the non-obese (Table 2). In addition, morbidly obese patients were more likely to be younger and less severely ill (based on systolic blood pressure [SBP] and lower percentage of ICU admissions). Mean creatinine was higher in this population, but the CrCl was also higher on average. As presented in Table 3, there was no observable difference in the clinical treatment of severe sepsis patients by BMI (e.g., rate of intubation or early goal-directed therapy [EGDT] use).

Association between BMI and mortality

The 28-day mortality for each BMI category is listed in Table 4. Data were grouped for obese and morbidly obese groups to facilitate multivariable analysis, given the small number of mortal events at 28 days (five) in the morbidly obese group. By combining the obese and morbidly obese groups, a total of 48 mortal events occurred, allowing us to enter six variables into our multivariable analysis. The unadjusted and adjusted associations between BMI and mortality are shown in Table 4. In unadjusted analysis, the combined group of obese and morbidly obese patients was significantly less likely to die (OR 0.67; CI 0.46, 0.97; p = 0.04).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted OR for the association between BMI category and 28-day mortality

| BMI category | OR | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||

| Underweight (n = 102) | 1.1 | 0.66, 1.83 | 0.70 |

| Normal (n = 480) | 1.0a | ||

| Overweight (n = 301) | 0.89 | 0.63, 1.28 | 0.54 |

| Obese and morbidly obese (n = 308) | 0.67 | 0.46, 0.97 | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for age and ED APACHE II | |||

| Underweight | 1.05 | 0.61, 1.80 | 0.86 |

| Normal | 1.0 | ||

| Overweight | 0.9 | 0.61, 1.31 | 0.57 |

| Obese and morbidly obese | 0.72 | 0.48, 1.06 | 0.10 |

| Adjusted for age, ED APACHE II, intubation, oncology service, initiation of early goal directed therapy, and creatinine clearance | |||

| Underweight | 0.76 | 0.42, 1.39 | 0.38 |

| Normal | 1.0 | ||

| Overweight | 0.86 | 0.57, 1.3 | 0.47 |

| Obese and morbidly obese | 0.66 | 0.42, 1.03 | 0.06 |

OR odds ratio, ED emergency department, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

aNormal group reference

Specifically, it was the morbidly obese group that had a significantly lower mortality compared to the normal group (6.5 vs. 22.0 %; p = 0.002). This relationship was demonstrated in the RCS model overlaid on the distribution plot, which demonstrated a decrease in mortality with increasing BMI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Restricted cube spline analysis demonstrating BMI distribution of study subjects, subject deaths, and mortality

However, after adjusting for potential covariates, the combined obese and morbidly obese group OR was essentially unchanged, and the CI were broader, resulting in a non-significant decreased risk of mortality compared to the normal group (adjusted OR 0.66; CI 0.42, 1.03; p = 0.06). After adjustment for potential covariates, no difference in mortality was detected between the underweight group and the normal group (OR 0.76; CI 0.42, 1.39; p = 0.39).

In post hoc analyses, the association between morbid obesity and mortality did not differ significantly after stratification by admission to an ICU vs. admission to a non-ICU (OR 0.44 and 0.38, respectively, test for homogeneity, p = 0.32).

There were no differences between groups when analyzed for the secondary outcomes of 60-day and 1-year mortality in unadjusted and adjusted models.

Association between BMI and hospital LOS

The median hospital LOS of the severe sepsis cohort was 6 days (IQR 4–12). The LOS did not differ across BMI category (p = 0.18). Further, the LOS did not differ after inclusion of mortality as an indicator variable, in the subgroup of patients who survived to hospital discharge, nor did ICU LOS differ between BMI groups in those admitted to an ICU (p = 0.92).

Discussion

In this retrospective observational cohort study of patients admitted through the ED with severe sepsis, we find evidence, using the RCS model, that morbidly obese patients have a significantly lower mortality compared to the normal BMI group (p < 0.001). However, after adjustment for potential confounding variables, the relationship between NIH obesity categories and mortality is no longer significant. Despite many hypotheses about the increased risk of complications and comorbidities in the underweight and obese BMI groups, our study does not validate the hypothesis that these cohorts of patients have increased severe sepsis mortality [7]. Rather, our results support those of prior studies of critically ill patients demonstrating no significant difference in mortality between different obesity strata [6, 7, 29]. Further, our results suggest that morbidly obese severe sepsis patients may be significantly less likely to die compared to patients with a normal BMI.

An examination of the baseline clinical characteristics across BMI groups reveals several plausible explanations for why, despite fulfilling criteria for severe sepsis, obese patients show a trend toward, and morbidly obese patients experience significantly lower mortality than normal BMI patients. Specifically, morbidly obese patients present in a less critically ill state than the other groups based on clinically significant differences in: age (younger,) hemodynamic status (higher minimum MAP,) laboratory values (higher CrCl despite higher serum creatinine levels,) lower mean calculated ED APACHE II scores, and lower MICU admission rate. Furthermore, along with the obese group, morbidly obese patients present much more frequently with severe sepsis due to skin or soft tissue infections than do those with lower BMIs. Despite the differences in presentation, the hospital LOS across BMI groups are comparable. These findings provide important information regarding the differences in the initial presentation and hospital course for severe sepsis patients with high BMI.

Alternatively, it is plausible that obese and morbidly obese patients have alterations in their basic physiology and immunologic responses to ischemia and infection that are protective as a patient becomes ill with a critical infection. For example, it has been proposed that obesity and commonly associated comorbidities including hypertension and diabetes diminish the protective effects of preconditioning [30]. How this affects the innate inflammatory response to diverse infectious pathogens is unclear. Also, innate inflammation may be altered in obese patients compared to those with a normal BMI. For example, similar alterations in mRNA and down-regulation in gene expression in adipose tissue are observed in obese patients and in experimental human endotoxemia [31]. Obese patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) demonstrate down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines when compared to normal weight ARDS patients [32].

The reasons for divergent findings from multiple studies examining the relationship between BMI and outcomes in critically ill patients are not fully explained by our study or prior investigations. Prior studies have been performed in diverse settings in diverse patient populations of varying severity of illness, and use different BMI cut-offs to define underweight and obesity. For example, a prospective cohort study (1,698 subjects) of patients admitted to six medical-surgical ICUs in France demonstrates an increased mortality for BMI <18.5 kg/m2 (OR 1.63; CI 1.11–2.39) and a decreased mortality for patients with BMI >30 kg/m2 (OR 0.60; CI 0.40–0.88) [6]. Similarly, a large multi-institutional ICU database (41,011 patients) shows an association between low BMI (<20 kg/m2) and increased mortality, but no differences in other BMI groups including the obese [7]. More recently, a large multicenter study (3,902 patients) from 24 ICUs in Italy demonstrates that being overweight or obese is associated with a decreased mortality in patients admitted to the ICU [29]. Similarly, utilizing a database of Medicare patients with severe sepsis, Powell and colleagues recently demonstrate that obese (OR 0.59, CI 0.39–0.88) and morbidly obese (OR 0.46, CI 0.16–0.80) severe sepsis patients have a lower mortality when compared to normal weight comparators [14].

Conversely, a small two-center cohort study of morbidly obese patients (BMI >40 kg/m2) demonstrates a longer duration of ICU stay, a longer duration of mechanical ventilation, and a higher mortality in the morbidly obese group [8]. A higher mortality for obese patients (defined as a BMI >27 kg/m2) was also demonstrated in a single-ICU study from France [9]. A meta-analysis of 14 studies, pooling 62,045 critically ill patients, 25 % of whom were obese (BMI>30 kg/m2), confirms the findings of a longer ICU LOS and a prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation, but demonstrates no difference in mortality (OR 1.00; CI 0.86–1.16; p = 0.97) [10].

Our study differs from all of these studies except the one by Powell et al. [14] in that all of the patients in our investigation are severe sepsis patients rather than a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients. Also, all of the patients we studied were admitted from the ED, rather than entering the ICU or wards from a variety of locations. Whether outcomes differ by BMI group in patients who develop severe sepsis after hospitalization for an alternate reason remains unclear. In addition, the breadth of our database allows for more granular, patient-level data than many larger databases. This allows for insights including that the lower mortality trend in obese and morbidly obese patients admitted with severe sepsis through the ED may be related to lower severity of illness and differences in location of infection (more cellulitis and soft tissue infections).

There are several limitations to our study. First, due to the retrospective design of our study, 10 % of patients who had severe sepsis during the study period were excluded due to missing BMI data. In addition, our retrospective design is potentially prone to selection and ascertainment bias. However, excluded patients were comparable to the included cohort in terms of age and severity of illness (Appendix 2–3). Second, the use of admission height and weight for BMI calculations is another potential limitation. Patient weight at presentation to the ED, or upon arrival to a hospital floor, will vary the degree of dehydration and the volume of fluid resuscitation delivered in the ED. This is likely to generate a non-differential bias given that processes of care in the ED did not differ by BMI, and weights were recorded prior to knowledge of the primary outcome. Further, BMI may not be an accurate predictor of risks associated with obesity, and a component of BMI may reflect volume overload not obesity in patients with congestive heart failure and other diseases. More nuanced analyses of the relationship between obesity and mortality may be obtained if a measure of functional status is included in the analysis, [33] or if the waist circumference is measured in addition to BMI [34]. We did not collect information on recent weight loss, and a recent weight loss of 10 % in a morbidly obese or underweight patient may compromise health and confer increased risk. Further, we did not collect data on nutrition consumed during hospitalization, and variations in the percent of daily requirements actually received during critical illness may have implications about outcomes. In addition, despite having a final cohort of 1,191 patients, the number of patients in the underweight group (102 patients), and combined obese and morbidly obese group (308 patients), may have been underpowered to find differences between them and other groups that were actually present thus producing a Type II error. Using a database of severe sepsis patients with a wide range of disease severity concentrated the primary outcome in a smaller cohort of patients, and this may have biased toward no difference in mortality being found between BMI categories. Finally, as a single-center study, the results may not be generalizable to other centers with different patient populations.

Conclusions

We find that 28-day mortality is neither significantly increased nor decreased in underweight or obese patient with severe sepsis; our results suggest that outcomes for the morbidly obese may be favorable due in part to different characteristics at presentation and source of infection. Prospective studies using larger patient populations, specifically in the extremes of BMI, are needed to validate these findings. Additional studies examining the relationship between obesity and sepsis-related morbidities including central venous catheter complications, decubitus ulcer formation, drug interactions, and readmission after discharge from the index severe sepsis hospitalization are warranted.

Conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- LOS

Length of stay

- ED

Emergency department

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- SIRS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- CrCl

Creatinine clearance

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- EGDT

Early goal-directed therapy

- SSDI

Social security death index

- PT

ProThrombin time

- PTT

Partial thromboplastin time

- GCS

Glasgow coma scale

- APACHE

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- SOFA

Sequential organ failure assessment

- MICU

Medical intensive care unit

- HTN

Hypertension

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CHF

Congestive heart failure

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

Appendix

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of the severe sepsis cohort

| Characteristics | Alive n = 954 | Deceased n = 237 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (IQR) | 55 (44–68) | 63 (53–73) | <0.001 |

| Male sex n (%) | 522 (54.7) | 129 (54.4) | 0.94 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 243 (25.5) | 51 (21.5) | 0.20 |

| Immunosuppressed n (%) | 281 (29.5) | 99 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension n (%) | 384 (40.3) | 81 (34.2) | 0.18 |

| Solid tumor with mets n (%) | 85 (8.9) | 75 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy in past 4 weeks n (%) | 159 (16.7) | 74 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| Oncology patient n (%) | 259 (27.1) | 132 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| Active tobacco use n (%) | 65 (6.8) | 23 (9.7) | 0.07 |

| Creatinine clearance, median ml/min (IQR) | 62.7 (33.2–93.9) | 46.1 (30.9–75.8) | <0.001 |

| ED APACHE II score, IQR | 14 (10–19) | 18 (13–23.5) | <0.001 |

| ED SOFA score, IQR | 3 (2–5) | 4 (3–7) | <0.001 |

IQR interquartile range, ED emergency department, APACHE II acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment

Table 6.

Comparison of cohort and excluded patients

| Characteristics | Included n = 1,191 | Excluded n = 133 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 (45–69) | 63 (46–78) | 0.01 |

| Male sex n (%) | 651 (54.7) | 76 (57.1) | 0.46 |

| APACHE II score | 14 (10–20) | 15 (10–22) | 0.33 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 6 (4–12) | 5 (3–9) | <0.001 |

| Intubated n (%) | 186 (15.6) | 19 (14.3) | 0.68 |

APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, LOS length of stay

Table 7.

Comparison of subjects with complete data to subjects with missing bmi data

| Characteristics | Complete BMI, n = 1,191 | Missing BMI, n = 68 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28-day mortality, n (%) | 237 (19.9) | 11 (16.2) | 0.49 |

| 60-day mortality, n (%) | 285 (23.9) | 12 (17.7) | 0.44 |

BMI body mass index

Contributor Information

Timothy Glen Gaulton, Email: tgaulton@gmail.com.

C. Marshall MacNabb, Email: Marshall.macnabb@respiratorymotion.com

Mark Evin Mikkelsen, Email: Mark.Mikkelsen@uphs.upenn.edu.

Anish Kumar Agarwal, Email: Anish.agarwal@uphs.upenn.edu.

S. Cham Sante, Email: Cham.Sante@yahoo.com

Chirag Vinay Shah, Email: chirags@paamds.com.

David Foster Gaieski, Phone: 215-503-1678, Phone: 302-588-7083, Email: david.gaieski@jefferson.edu.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan M, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Abrahamian FM, et al. Severe sepsis and septic shock: review of the literature and emergency department management guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:28–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troiano RP, Frongillo EA, Jr, Sobal J, Levitsky DA. The relationship between body weight and mortality: a quantitative analysis of combined information from existing studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Troche G, Azoulay E, et al. Body mass index. An additional prognostic factor in ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremblay A, Bandi V. Impact of body mass index on outcomes following critical care. Chest. 2003;123:1202–1207. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Solh A, Sikka P, Bozkanat E, Jaafar W, Davies J. Morbid obesity in the medical ICU. Chest. 2001;120:1989–1997. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulenok C, Monchi M, Chiche J-D, Mira JP, Dhainaut JFo, Cariou A. Influence of overweight on ICU mortality. Chest. 2004;125:1441–1445. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinnusi ME, Pineda LA, El Solh AA. Effect of obesity on intensive care morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:151–158. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000297885.60037.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frat JP, Gissot V, Ragot S, et al. Impact of obesity in mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1991–1998. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1245-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray DE, Matchett SC, Baker K, Wasser T, Young MJ. The effect of body mass index on patient outcomes in a medical ICU. Chest. 2005;127:2125–2131. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakr Y, Madl C, Filipescu D, et al. Obesity is associated with increased morbidity but not mortality in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1999–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott HC, Chang VW, O’Brien JR, JM, Langa KM, Iwashyna T (2014) Obesity and 1-year outcomes in older americans with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Shor-Posner G, Campa A, Zhang G, et al. When obesity is desirable: a longitudinal study of the Miami HIV-1-infected drug abusers (MIDAS) cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:81–88. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200001010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischmann E, Teal N, Dudley J, May W, Bower JD, Salahudeen AK. Influence of excess weight on mortality and hospital stay in 1346 hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1560–1567. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grady KL, White-Williams C, Naftel D, et al. Are preoperative obesity and cachexia risk factors for post heart transplant morbidity and mortality: a multi-institutional study of preoperative weight-height indices. Cardiac Transplant Research Database (CTRD) Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:750–763. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(99)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW., Jr Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1097–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoit BD, Gilpin EA, Maisel AA, Henning H, Carlisle J, Ross J., Jr Influence of obesity on morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1987;114:1334–1341. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choban PS, Weireter LJ, Jr, Maynes C. Obesity and increased mortality in blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1991;31:1253–1257. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedlund J, Hansson LO, Ortqvist A. Short- and long-term prognosis for middle-aged and elderly patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: impact of nutritional and inflammatory factors. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:32–37. doi: 10.3109/00365549509018970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris AE, Stapleton RD, Rubenfeld GD, Hudson LD, Caldwell E, Steinberg KP. The association between body mass index and clinical outcomes in acute lung injury*. Chest. 2007;131:342–348. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikkelsen M, Miltiades A, Gaieski D, et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1670–1677. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification Evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults-the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Statist Med. 2010;29:1037–1057. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakr Y, Elia C, Mascia L, Barberis B, et al. Being overweight or obese is associated with decreased mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective analysis of a large regional Italian multicenter cohort. J Crit Care. 2012;27:414–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sack MN, Murphy E. The role of comorbidities in cardioprotection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:267–272. doi: 10.1177/1074248411408313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah R, Hinkle CC, Haris L, et al. Adipose genes down-regulated during experimental endotoxemia are also suppressed in obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E2152–E2159. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stapleton RD, Dixon AE, Parsons PE, et al. The association between body mass index and plasma cytokine levels in patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2010;138:568–577. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padwal RS, Pajewski NM, Allison DB, Sharma AM. Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ. 2011;183(14):E1059–E1066. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang HE, Griffin R, Judd S et al (2013) Obesity and risk of sepsis: A population-based cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring) (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]