Abstract

Background

Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019(COVID-19) will experience high levels of anxiety and low sleep quality due to isolation treatment. Some sleep-improving drugs may inhibit the respiratory system and worsen the condition. Prolonged bedside instruction may increase the risk of medical infections.

Objective

To investigate the effect of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality of COVID-19.

Methods

In this randomized controlled clinical trial, a total of 51 patients who entered the isolation ward were included in the study and randomly divided into experimental and control groups. The experimental group used progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) technology for 30 min per day for 5 consecutive days. During this period, the control group received only routine care and treatment. Before and after the intervention, the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI) and Sleep State Self-Rating Scale (SRSS) were used to measure and record patient anxiety and sleep quality. Finally, data analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software.

Results

The average anxiety score (STAI) before intervention was not statistically significant (P = 0.730), and the average anxiety score after intervention was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The average sleep quality score (SRSS) of the two groups before intervention was not statistically significant (P = 0.838), and it was statistically significant after intervention (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Progressive muscle relaxation as an auxiliary method can reduce anxiety and improve sleep quality in patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: Progressive muscle relaxation, COVID-19, Anxiety, Sleep quality

Highlights

-

•

In patients with COVID-19, all confirmed patients need to be treated in isolation due to strong infectivity. According to clinical observation, anxiety and sleep disturbances increased significantly after isolation treatment. Some sleep-promoting drugs may have respiratory depression, and the new coronary virus mainly affects lung tissue, and the use of drugs may increase respiratory depression. Therefore, we use asymptotic muscle relaxation training to alleviate the anxiety and improve sleep quality of patients with COVID-19. This training can be performed remotely and multiple times after one training session, without directly facing the patient, reducing doctor-patient contact and reducing medical infection risk. Currently, COVID-19 has a large number of cases in South Korea, Japan, Iran, and Italy. I hope our clinical research will be helpful to our country's clinical treatment and the above countries.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown cause emerged in Wuhan, Hubei, China, with clinical presentations greatly resembling viral pneumonia. Deep sequencing analysis from lower respiratory tract samples indicated a novel coronavirus, which was named 2019 novel coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Based on the current epidemiological investigation, the incubation period is 1–14 days, mostly 3–7 days. Fever, dry cough, and fatigue are the main manifestations [1]. With the spread of the epidemic, other cases have been found in other parts of China and abroad. The sources of infection seen so far are mainly patients with new type of coronavirus infection, which are mainly transmitted through respiratory droplets and close contact. Patients diagnosed with this disease must be treated in isolation. Through clinical observation, many patients developed anxiety and sleep disturbances after isolation treatment. Anxiety, as a kind of psychological stress, will trigger a series of physiological events and cause a decrease in immunity [2].

Because the symptoms are mild in the early stage, but can suddenly worsen after a few days, the use of benzodiazepine-type sleep-promoting drugs may cause respiratory depression and delay the observation of the disease. Progressive muscle relaxation is a deep muscle relaxation method based on the principle that muscle tension is the physiological response of the human body to irritating thinking [3]. This technology was developed by Jacobsen in 1938, in which the body and mind are greatly relieved from any tension and anxiety. In a study by Aksu [4]: Progressive muscle relaxation improves sleep quality in patients with pneumonectomy. Progressive muscle relaxation is easy to learn, does not require specific time and place, and does not require special technology and equipment. Therefore, this study aims to explore the effect of progressive muscle relaxation on sleep quality and anxiety in patients with COVID-19.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design and participants

A total of 51 patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to the Hainan General Hospital from January 1 to February 16, 2020 were included in the study. The patients were randomly divided into two groups (experimental group and control group), and the participants were intervened in the order of the beds. This study is a randomized controlled clinical trial approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Provincial People's Hospital. All patients performed verbal informed consent because of progressive muscle relaxation training without any trauma and considering the strong infectivity of the new coronavirus.

2.2. STAI and SRSS questionnaire

The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI) was used to assess anxiety state, and the Sleep State Self-Rating Scale (SRSS) was used to assess sleep state. The STAI questionnaire score ranges from 20 to 80 points and is divided into four groups: no anxiety (≤20), mild (21–39), moderate (40–59), and severe anxiety (60–80). The Sleep Condition Self-Assessment Scale (SRSS) is designed to assess the sleep quality of hospitalized patients. There are 10 items in total. Each item has a 5-point scale (1–5). The higher the score, the more serious the sleep problem. This scale has a minimum score of 10 (basically no sleep problems) and a maximum score of 50 (most severe). Participants completed the questionnaire before and after the intervention.

2.3. Data collection

The patient's age, gender, symptoms, chest CT results, and previous history of using hypnotic drugs were collected by electronic medical records. Before starting the study, the doctor provided an explanation of the goals and methods. All participants were fully included in the study with personal consent, were free to leave the study at any stage, and ensured that the data collected was confidential, so the names of the participants were not listed in the results.

2.4. Intervention

First, the questionnaires were collected from the experimental and control groups before the intervention. The researchers then instructed the experimental group on how to relax using Jacobson's relaxation techniques (progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing), and after determining that they had learned how to relax, the patients performed this within 20–30 min each day, training for 5 consecutive days. The trainee chooses a relaxed supine position, and starts with the hand through the hospital call system under the guidance of the medical staff, followed by the upper limbs, shoulders, head, neck, chest, abdomen, and finally the lower limbs. Right, if the trainer first left arm and then right arm, the rest of the movement can follow this principle. During muscle tension, the action can be performed for 10–15 s, and the relaxation process can be 15–20 s; each group of muscles is repeatedly trained 3 times in sequence; the training time is generally selected once at noon and before falling asleep, each time 20–30 min. At the same time, the patient takes a deep breath, inhales through his nose, and exhales through his mouth. Patients in the control group received routine care during this period. The anxiety and sleep quality of the two groups were measured after the 5-day intervention.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 software and descriptive and inferential statistical methods. In addition, the level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Chi-square and t-tests were used to compare nominal data and average scores for anxiety and sleep quality, respectively.

3. Results

In this study, men accounted for 56% of the experimental group and 53.85% of the control group. The overall mean age of the patients was 50.41 ± 13.04 years. Fever was the most common symptom in patients in this study (80.39%). In clinical symptoms, the extent of lung lesions based on chest CT did not differ significantly between the two groups, whether or not they used hypnotic drugs, gender, and age (P > 0.05, Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Use chi square test to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of the control group and the intervention group.

| variable | Experimental group (n = 25) | Control group (n = 26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male,n (%) | 14 (56.00%) | 14 (53.85%) | 0.877 |

| female,n (%) | 11 (44.00%) | 12 (46.15%) | 0.877 |

| Range (years) | |||

| 20–35 | 4 (16.00%) | 5 (19.23%) | 1.000 |

| 36–50 | 8 (32.00%) | 8 (30.77%) | 0.925 |

| 51–65 | 9 (36.00%) | 8 (30.77%) | 0.692 |

| ≥65 | 4 (16.00%) | 5 (19.23%) | 1.000 |

| Clinical symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Fever | 17 (68.00%) | 24 (92.31%) | 0.067 |

| 37.3–38.0 °C | 3 (12.00%) | 8 (30.77%) | |

| 38.1–39.0 °C | 9 (36.00%) | 10 (38.46%) | |

| >39.0 °C | 5 (20.00%) | 6 (23.08%) | |

| Cough and sputum | 10 (40.00%) | 11 (42.31%) | 0.867 |

| Fatigue | 3 (12.00%) | 4 (15.38%) | 1.000 |

| Headache | 2 (8.00%) | 3 (11.54%) | 1.000 |

| Haemoptysis | 1 (4.00%) | 1 (3.84%) | 0.663 |

| Diarrhoea | 2 (8.00%) | 3 (11.54%) | 0.468 |

| Dyspnoea | 1 (4.00%) | 3 (11.54%) | 0.512 |

| Asymptomatic | 2 (8.00%) | 3 (11.54%) | 1.000 |

| Lung CT lesion range, n (%) | |||

| Multiple lobes | 17 (68.00%) | 19 (73.07%) | 0.691 |

| Single lobe | 8 (32.00%) | 7 (26.92%) | 0.691 |

| Previous sedative use, n (%) | |||

| Benzodiazepines | 3 (12.00%) | 2 (7.69%) | 0.963 |

| Non-benzodiazepines | 2 (8.00%) | 1 (3.85%) | 0.972 |

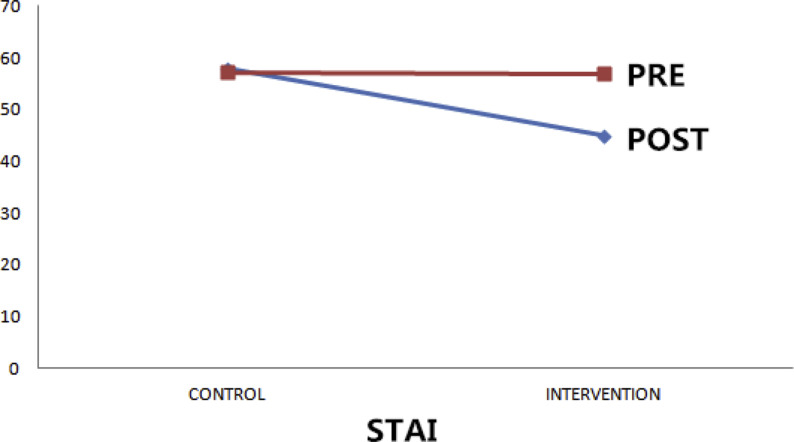

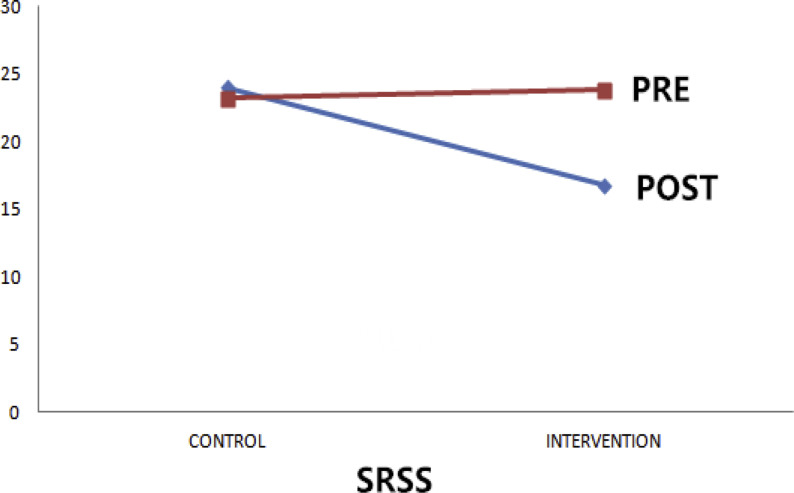

All patients completed the study without data leakage. The average score of sleep quality before intervention in the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.927), and there was statistical significance after intervention (P < 0.05). The t-test results also showed that the average score of anxiety before intervention was not statistically significant (P = 0.713), and the average score of anxiety after intervention was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ) (Table 2 ). In this study, compared with the control group, the experimental group had reduced anxiety levels and improved sleep quality after 5 days (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Changes of anxiety level (STAI) before and after intervention.

Fig. 2.

Changes of sleep quality score (SRSS) before and after intervention.

Table 2.

Comparison of anxiety and sleep quality scores between control group and intervention group before and after intervention.

| variable | Experimental group (n = 25) | Control group(n = 26) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAI | Before intervention | 57.88 ± 11.51 | 56.92 ± 7.92 | 0.730 |

| After intervention | 44.96 ± 12.68 | 57.15 ± 9.24 | <0.001 | |

| SRSS | Before intervention | 24.04 ± 3.87 | 23.85 ± 2.82 | 0.838 |

| After intervention | 16.76 ± 4.10 | 23.23 ± 2.70 | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19 in a progressive muscle relaxation training team. The results show that PMR is an effective way to reduce anxiety and improve sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. The results of studies on the effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety levels in young women [5], prenatal anxiety [6], and early breast cancer [7] female patients are consistent with this study. In addition, our study found that PMR also affects the quality of sleep in patients with COVID-19. Previous studies have shown the impact of this technology on the sleep quality of other patients, and found that PMR can reduce complications and improve sleep quality of patients with fractures [8]. Seyedi [9] and others also showed that PMR can reduce fatigue and improve sleep quality in patients with COPD. PMR is also effective for pain intensity and sleep quality after cesarean section. Although the efficacy of this method has been confirmed in domestic studies, it is the first time it has been used in patients with COVID-19. Due to the strong infectivity of the disease, PMR training can be implemented remotely to reduce the use of hypnotic drugs and reduce the risk of medical infection. The reason for the decrease in anxiety of patients after PMR training may be the balance between the anterior and hypothalamic nucleus. By reducing the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, side effects of stress and anxiety can be prevented, and physical and mental relaxation can be increased [10]. Similar to other studies, patients in this study achieved relaxation by learning how to regularly tighten and relax muscles and identify symptoms of stress.

However, studies have shown that the technology has no significant effect on improving patients' sleep problems compared to other rehabilitation methods. The study of the effect of progressive muscle relaxation on sleep quality in emergency trauma patients by Masih [11] and others is inconsistent with the results of this study. Although there were significant differences in sleep quality scores before and after the intervention in the experimental group, there was no significant difference between them. In a study by Hasanpour-Dehkordi [12] and others on patients with chronic pain, two methods of muscle relaxation and hypnosis were used to reduce pain, but the results showed that neither method was effective. The inconsistency between our results and the above results can be attributed to the study population. The variables studied are related to the psychological fear caused by the current patients' insufficient understanding of the COVID-19.

According to the results of this study, progressive muscle relaxation has a positive effect on improving sleep quality and reducing anxiety in patients with COVID-19. Due to the strong contagion of COVID-19, isolation treatment and the effects of drugs on patients increase their levels of anxiety and sleep disorders. Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that the PMR regimen be taught to the caregiver and done by the patient, and compared with other adjuvant therapies.

5. Limitations

The limitations of our study are the individual differences and psychological conditions of the sample, the influence of environmental and cultural factors on the individual, and the patient's attention during the hospital stay.

Ethics

Committee Number: HGHEC: 20200115003.

Authors’ contribution

DZW conceived of the initial idea for the study and helped to study design. KL designed the study, collected data, and performed the statistical analysis. ZSW and YC contributed to intervention design and to draft the manuscript. RZL helped to recruit the participants. LQP helped to intervention design and to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101132.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. published online Jan 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajeswari S., SanjeevaReddy N. Efficacy of progressive muscle relaxation on pregnancy outcome among anxious Indian primi mothers. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019;25:23–30. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_207_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cougle J.R., Wilver N.L., Day T.N. Interpretation bias modification versus progressive muscle relaxation for social anxiety disorder: a web-based controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 2020;51:99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aksu N.T., Erdogan A., Ozgur N. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation training on sleep and quality of life in patients with pulmonary resection. Sleep Breath. 2018;22:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilczyńska D., Łysak-Radomska A., Podczarska-Głowacka M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of relaxation in lowering the level of anxiety in young adults - a pilot study. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 2019;32:817–824. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajeswari S., SanjeevaReddy N. Efficacy of progressive muscle relaxation on pregnancy outcome among anxious Indian primi mothers. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019;25:23–30. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_207_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gok Metin Z., Karadas C., Izgu N. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation and mindfulness meditation on fatigue, coping styles, and quality of life in early breast cancer patients: an assessor blinded, three-arm, randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019;42:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie L.Q., Deng Y.L., Zhang J.P. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation intervention in extremity fracture surgery patients. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016;38:155–168. doi: 10.1177/0193945914551509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seyedi Chegeni P., Gholami M., Azargoon A. The effect of progressive muscle relaxation on the management of fatigue and quality of sleep in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Compl. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018;31:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferendiuk E., Biegańska J.M., Kazana P. Progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson in treatment of the patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. Folia Med. Cracov. 2019;59:113–122. doi: 10.24425/fmc.2019.131140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masih T., Dimmock J.A., Guelfi K.J. The effect of a single, brief practice of progressive muscle relaxation after exposure to an acute stressor on subsequent energy intake. Stress Health. 2019;35:595–606. doi: 10.1002/smi.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasanpour-Dehkordi A., Solati K., Tali S.S. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation with analgesic on anxiety status and pain in surgical patients. Br. J. Nurs. 2019;28:174–178. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.3.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.