Abstract

Myocarditis is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening disease. Clinical manifestations could range from subclinical disease to sudden death, due to fulminant heart failure and/or malignant ventricular arrhythmias. The most common cause of myocarditis is viral infection, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Nevertheless, EBV rarely presents with cardiac involvement in immunocompetent hosts.

We report a case of acute EBV-related myocarditis in a young female, complicated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest. After 20 days of hospitalization and treatment, the patient was fit for discharge on pharmacological therapy (tapering steroids, beta-blockers, amiodarone, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and diuretics). Clinical course is described, cardiac magnetic resonance images are shown.

This case underlines how myocarditis is a disease that should not be underestimated: it could present with life-threatening complications such as malignant arrhythmias and/or severe systolic dysfunction.

<Learning objective: Although Epstein-Barr virus rarely presents with cardiac involvement in immunocompetent hosts, the risk should not be underestimated, as it could present with life-threatening complications.>

Keywords: Myocarditis, Viral infection, Epstein-Barr, Heart failure, Cardiac arrest

Introduction

Myocarditis is an uncommon disease and its clinical manifestations are highly variable, including life-threatening conditions such as malignant arrhythmias and/or severe systolic dysfunction. Viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, are most frequently involved in the etiology of myocarditis and generally present a benign course [1]. A significant cardiac injury is unusual during an EBV infection.

We report a case of acute EBV-related myocarditis, complicated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest. After hospitalization and optimal medical therapy, the patient was discharged with improved clinical status albeit residual severe left ventricular dysfunction.

Case report

A previously healthy 20-year-old female sought medical attention while studying abroad in Rome, Italy. As she did not speak Italian, she requested a house call through an English-speaking medical provider. She reported cold-like symptoms, fatigue, cough, and odynophagia lasting a week. Physical examination revealed cervical lymphadenopathy and tonsillar hypertrophy, with purulent exudate, and no fever. The patient was started on an empiric antibiotic course with macrolides. Two weeks after the first assessment, she reported the onset of mild non-radiating chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, and reduced exercise tolerance, without symptoms at rest. Thus, she underwent a cardiological evaluation: physical examination was unremarkable, blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm of 90 bpm, normal atrioventricular tract, no repolarization abnormalities. An echocardiogram showed reduced ejection fraction (40–45%) with global hypokinesia and no regional wall motion abnormalities, mild pericardial effusion along the right chambers without signs of tamponade. The patient was then referred for immediate hospitalization.

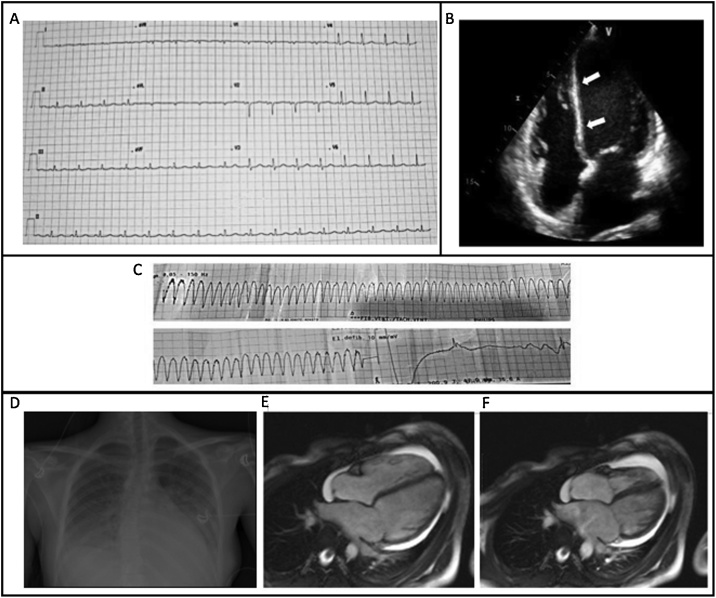

On admission, the patient was in good general condition, symptomatic for chest pain and mild dyspnea, worsening with inspiration. Physical examination was substantially normal. Blood pressure was 90/70 mmHg, ECG (Fig. 1A) showed sinus rhythm (95 bpm), normal AV and IV conduction, diffuse low voltages, normal repolarization. An echocardiogram showed hypo-dyskinesia of the interventricular septum, which appeared thinned and hyper-reflective, and hypokinesia of mid-basal walls with a reduced ejection fraction (40%); valves were normally-functioning, circumferential pericardial effusion without compression was reported (Fig. 1B). Myocardial necrosis markers, elevated on admission, are reported in Table 1A. Diagnosis of myo-pericarditis was entertained and the patient was placed under ECG monitoring; heart-failure therapy (diuretics, beta-blockers, and anti-inflammatory drugs) was started.

Fig. 1.

Instrumental findings. (A) Electrocardiogram at the hospitalization. (B) View from the echocardiogram performed at the admission. The interventricular septum appears thinned and hyper-reflective (C) Ventricular tachycardia and shock. (D) Bedside chest X-ray at the admission to the intensive care unit. It shows bilateral pleural effusion and signs of pulmonary interstitial edema. (E,F) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Frames from a cine series at the end-diastole (E) and end-systole (F), showing severe reduction of left ventricular function (30%) with associated global hypokinesia.

Table 1.

(A) Myocardial necrosis markers temporal changes. (B) Infectious disease and immunological screening conducted for differential diagnosis of myocarditis etiology.

| A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TnI ng/ml (0.02–0.05) | CkMb ng/ml (0.5–3.6) | Myoglobin ng/ml (13–71) | |

| Day 1 | 0.46 | 1.27 | 27 |

| Day 2 | 0.33 | 1.08 | 106 |

| Day 3 | 0.24 | 1.17 | 30 |

| Day 4 | 0.18 | 1.5 | 25 |

| Day 5 | 0.11 | 1 | 22 |

| Day 7 | 0.07 | <1 | 24 |

| Day 11 | 0.03 | <1 | 30 |

| Day 18 | 0.02 | 1 | 25 |

| B | |

|---|---|

| Negative | Positive |

| Adenovirus | EBV VCA IgM > 160 U/ml (<20) |

| Coronavirus | EBV VCA IgG 24.5 U/ml (<20) |

| Influenza Virus A/B | EBV EA IgG 17.40 U/ml (<10) |

| Parainfluenza Virus 1,2,3,4 | Rhinovirus |

| Echovirus | |

| Coxsackievirus | |

| Metapneumovirus | |

| Varicella Zoster Virus | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | |

| Bocavirus | |

| Enterovirus | |

| HIV 1-2 | |

| ANA | |

| ASMA | |

| ENA | |

| Fungal and bacterial throat swab culture | |

| EBV EBNA IgG < 3 (<5) | |

Table B. HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; ANA: Anti-Nuclear Antibodies; ASMA: Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibodies; ENA: Extractable Nuclear Antigens; EBV: Epstein-Barr Virus; EBNA: Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen; VCA: Viral Capsid Antigen; EA: Early Antigen; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; IgM: Immunoglobulin M.

The morning following admission, the patient experienced ventricular tachycardia, and sinus rhythm was restored with cardiopulmonary resuscitation and delivery of DC biphasic shock at 200 J (Fig. 1C). After a few minutes, a brief phase of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, not associated with hemodynamic instability, appeared. IV therapy with amiodarone was started. An echocardiogram showed severe reduction of the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (25%) and a chest X-ray exhibited bilateral pleural effusion with pulmonary interstitial edema (Fig. 1D); arterial-blood-gas test on room air showed respiratory failure. Adjunctive treatment with antibiotics and O2-therapy with non-invasive ventilation was initiated.

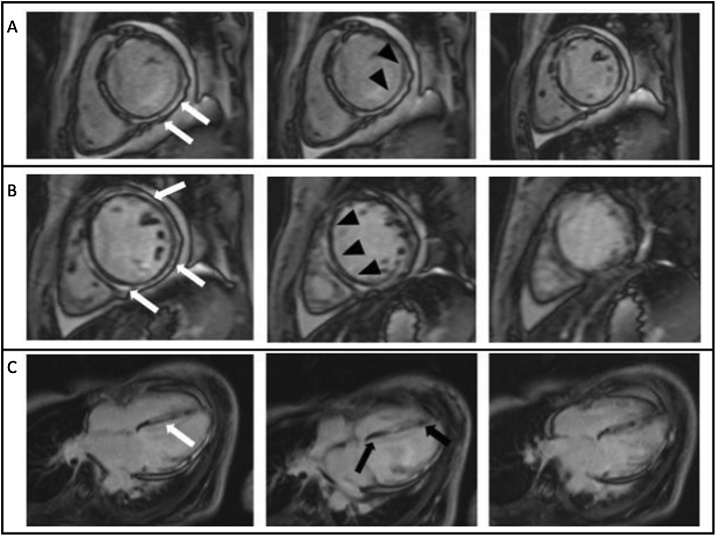

Several echocardiograms showed persisting severe LV dysfunction (ejection fraction 30–35%) with hypokinesis of mid-basal walls with normal contractility of the apex, circumferential pericardial effusion without chamber compression. The X-ray chest and High-resolution computed-tomography chest showed a progressively reduced bilateral pleural effusion, interstitial-alveolar edema with bilateral hilar congestion. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed severe reduction of LV function (ejection fraction 30%), with global hypokinesia, akinesia of infero-lateral wall, and septal dyskinesia. In delayed enhancement images, diffuse and global subepicardial and intramyocardial enhancement (not ischemic pattern), with parietal edema, were seen. The MRI findings were suggestive for acute myocarditis (Figs. 1E,F, 2 ). Although endomyocardial biopsy is the diagnostic gold standard, the patient was unconvinced to give consent to the procedure.

Fig. 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, late gadolinium enhancement - short axis (A,B) and 4 chambers (C). The images show global and diffuse enhancement with a subepicardial – intramyocardial pattern of distribution (white arrows), that involve all cardiac walls, except a little portion of the basal and apical septum (black arrows, C). Subendocardium is preserved (arrowheads, A,B).

To evaluate the etiology of the myocarditis, infectious disease and immunological screening were performed (Table 1B), suggesting an active EBV infection. As EBV-related hepatitis is a frequent finding, liver function tests were performed, excluding disease based on normal results both on admission and discharge.

Therapy with IV steroids (methylprednisolone 40 mg BID) was started. A chest X-ray showed a significantly reduced pleural effusion. The patient also suffered from a transient leukopenia and neutropenia, which required a 3-day isolation. An ECG performed on day 12 showed a prolonged QTc (520 ms), despite normal amiodarone levels.

During discharge planning, a transthoracic echocardiogram showed mild LV dilation with global hypokinesia, particularly in the inferior intraventricular septum and inferior wall, ejection fraction 33% II-degree diastolic dysfunction was detected with mildly dilated left atrium. The right chambers were normal with preserved contractility, and a circumferential pericardial effusion, without compression on the cardiac chambers was reported. On day 19, a Holter ECG showed sinus bradycardia, with frequent ventricular extra-systoles and three runs of junctional tachycardia. After decreasing amiodarone to 100 mg/day, long QTc resolved.

The patient was considered fit for discharge to return to the USA under the care of local specialists, on a pharmacological therapy consisting of tapering steroids, beta-blockers, amiodarone, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and diuretics and a final diagnosis of acute EBV–related myo-pericarditis complicated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest and severe residual LV dysfunction (ejection fraction 33%) with global hypokinesia.

Discussion

Myocarditis is an uncommon, potentially life-threatening disease which may present with a wide range of symptoms. Although the specific etiology of myocarditis often remains undefined, viral infection is the most common cause. EBV is a rare cause of myo-pericarditis in immune-competent patients: cardiac symptoms during EBV infection are uncommon and cardiac involvement is exceptional [2]. Clinical manifestations of myocarditis range from subclinical disease to sudden death, due to fulminant heart failure and/or malignant ventricular arrhythmias; cardiac symptoms include fatigue, palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, decreased exercise tolerance, or syncope. A viral prodrome including rash, myo-arthralgias, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms could anticipate the onset of myocarditis by several days to a few weeks [3].

ECG findings in myocarditis include sinus tachycardia, ST- and T-wave changes, and atrioventricular or bundle branch block; PR depression and diffuse ST elevation are usually due to an associated pericarditis.

Echocardiography is useful to rule-out valve diseases and to monitor myocarditis progression and response to therapy. Global ventricular dysfunction, wall thickness, regional motion abnormalities, and also diastolic dysfunction could occur in myocarditis [4]. Right ventricle dysfunction is uncommon but, if present, has an important prognostic value, representing the main predictor of death or transplantation [1].

Cardiac MRI can be a useful and non-invasive tool to diagnose myocarditis and monitor disease progression [5]. In particular, T1 and T2-weighted images evaluate hyperemia and capillary leakage, necrosis and fibrosis, and intracellular and interstitial edema — 3 markers of tissue injury [5]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that native T1 image can improve diagnostic accuracy of cardiac magnetic resonance in acute myocarditis [6]. Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) confirms the diagnosis of myocarditis and recognizes the etiology and the type of inflammation. Although EMB is the gold standard for the diagnosis of definite myocarditis [7], it is not a routine practice. In our case, the diagnosis was entertained using non-invasive tools and clinical presentation, making EMB not necessary.

The main principles of the treatment are optimal care of heart failure and arrhythmia and, when possible, etiology targeted therapy [8].

The natural history of myocarditis is heterogeneous: it varies from death due to severe systolic dysfunction and/or ventricular arrhythmias, to complete recovery or long-term evolution to dilated cardiomyopathy. The clinical presentation has an important prognostic value: in patients with heart failure at the onset, the need for transplant and cardiac death are significantly more likely [9].

Conclusion

We report a case of acute EBV-related myocarditis that occurred in a young immunocompetent woman while studying abroad in Italy. Although EBV infection is common in the general population, especially in young people, a significant heart injury is unusual.

This case underlines how myocarditis, although uncommon, should not be underestimated: as in the case reported, myocarditis could present, still and especially in young patients, with life-threatening conditions such as malignant arrhythmias and/or severe systolic dysfunction.

The elimination of language barriers has certainly contributed to prevent a worse outcome of the case. Although Italy is one of the most visited countries by students studying abroad, finding English-speaking health care professionals is still challenging. It is reassuring that an increasing number of hospitals have achieved the JCI accreditation and that private non-profit networks of certified English-speaking doctors are arising [10].

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.D’Ambrosio A., Patti G., Manzoli A., Sinagra G., Di Lenarda A., Silvestri F. The fate of acute myocarditis between spontaneous improvement and evolution to dilated cardiomyopathy: a review. Heart. 2001;85:499–504. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.5.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roubille F., Gahide G., Moore-Morris T., Granier M., Davy J.M., Vernhet H. Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and acute myopericarditis in an immunocompetent patient: first demonstrated case and discussion. Intern Med. 2008;47:627–629. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindermann I., Barth C., Mahfoud F., Ukena C., Lenski M., Yilmaz A. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:779–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felker G.M., Boehmer J.P., Hruban R.H., Hutchins G.M., Kasper E.K., Baughman K.L. Echocardiographic findings in fulminant and acute myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich M.G., Sechtem U., Schulz-Menger J., Holmvang G., Alakija P., Cooper L.T. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a JACC white paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1475–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotanidis C.P., Bazmpani M.A., Haidich A.B., Karvounis C., Antoniades C., Karamitsos T.D. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute myocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leone O., Veinot J.P., Angelini A., Baandrup U.T., Basso C., Berry G. 2011 consensus statement on endomyocardial biopsy from the Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology and the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2012;21:245–274. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caforio A.L., Pankuweit S., Arbustini E., Basso C., Gimeno-Blanes J., Felix S.B. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2636–2648. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210. 48a–8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinagra G., Anzini M., Pereira N.L., Bussani R., Finocchiaro G., Bartunek J. Myocarditis in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1256–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doctors in Italy. Italian Association of English-speaking doctors. https://www.doctorsinitaly.org.