Abstract

Viruses infect their human hosts by a series of interactions between viral and host proteins, indicating that detailed knowledge of such virus-host interaction interfaces are critical for our understanding of viral infection mechanisms, disease etiology and the development of new drugs. In this review, we primarily survey human host-virus interaction data that are available from public databases following the standardized PSI-MS format. Notably, available host-virus protein interaction information is strongly biased toward a small number of virus families including herpesviridae, papillomaviridae, orthomyxoviridae and retroviridae. While we explore the reliability and relevance of these protein interactions we also survey the current knowledge about viruses functional and topological targets. Furthermore, we assess emerging frontiers of host-virus protein interaction research, focusing on protein interaction interfaces of hosts that are infected by different viruses and viruses that infect multiple hosts. Finally, we cover the current status of research that investigates the relationships of virus-targeted host proteins to other comorbidities as well as the influence of host-virus protein interactions on human metabolism.

Keywords: Protein interaction network, Phage, Burden of disease, Interaction databases

1. Introduction

Bacteria and viruses are the most important pathogens on earth. While most bacteria can be directly eliminated with antibiotics, viruses can only be constrained in their growth, posing a challenge for treatment. This observation is a direct consequence of the fact that viruses are composed of only nucleic acids, proteins, sometimes lipids and a few other compounds. Thus, the survival of viruses is almost entirely dependent on molecular protein-protein interactions (PPI) with their hosts. Furthermore, viral variation occurs rapidly, often with significant adaptation within each host [1]. Hence, strategies for the development of safe antivirals often depend on precise targeting of virus-host PPIs and a deep understanding of viral biology.

In this review we relate the diversity of viruses to their medical importance. We use the number of currently known virus-host PPIs as a proxy for our knowledge of virus biology. Given the vast body of literature about virus-host interactions, we primarily base our review on data of human host-virus interactions available in public databases. Although extensive sequence information from next-generation sequencing studies exists, precise knowledge of virus-host PPIs and thus potential targets for antiviral therapies is rather limited, biased and incomplete. Medically important viruses such as HIV and Influenza have received considerable research attention, while other highly infectious viruses have received relatively little attention, as their spread is geographically limited and focused on a narrow range of hosts. Furthermore, their investigation may prove experimentally difficult or accelerated only recently. For example, the Zika threat is relatively recent, having triggered much research activity only in the last few years.

2. Diversity and morbidity of human viruses

As our interest in viruses is primarily driven by their impact on human health and economic toll we wonder how their medical and economic importance is related to research efforts, reflected by the number of genomes sequenced and the number of host-virus PPIs detected. Unsurprisingly, some viruses received a lot of attention. For example, both HIV and Influenza claim a large number of victims and impose a significant economic burden. In turn, viruses such as Hepatitis, MERS and SARS claim relatively few lives, yet come with a considerable economic price tag (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Human disease burden by viruses. Infections include infected number of people while morbidity and mortality include those that get sick or die, respectively. Cost is the economic damage of these viral diseases from hospitalization or lost work time. Unless otherwise indicated, figures are yearly.

| Virus (species) | Virus (family) | Infections | Morbidity | Mortality | Cost | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1/2 | Herpesviridae | 3.7 B / ∼700M | 3M/yr US | low | $540 M US | [[84], [85], [86], [87], [88]] |

| HIV-1/2 | Retroviridae | 36 M ww | 2.1 M/yr ww | 25 M ww total1 | $13.7B US | [89] |

| Influenza A | Orthomyxoviridae | >30 M US3 | 100-600 K US4 | 50 M 19182 ww | $10-90B | [[90], [91], [92]] |

| Measles morbillivirus | Paramyxoviridae | >20 M ww | 250k ww | 140-500k5 ww | $3-7B US | [93] |

| Hepatitis C | Flaviviridae | 60-120 M ww | 4M ww | 500k ww | $10B6 | [94,95] |

| Hepatitis B | Hepadnaviridae | 248 M ww/yr, ∼2.5 B ww total | 350 M ww total | 600k ww | $1B US | [[96], [97], [98]] |

| Zika virus | Flaviviridae | 740k SA | >2.6k7 SA | low | $18B ww | [99] |

| MERS-CoV | Coronaviridae | 2067 ww total | 1179 ww total | 720 ww total | $15-20B | [100] |

| SARS-CoV | Coronaviridae | >10k ww total | 8098 ww total | 774 ww total | $40B ww | [101,102] |

| Rhinovirus A, B, C | Picornaviridae | 1B/year US | 10-40% of common colds | low | $20B US | [103] |

| Norovirus (Norwalk virus) | Caliciviridae | 19-21 M US; 685 M ww | 699 M ww | 570-800 US; 200 K children ww; 219 K ww | $4.2B indirect; $60.3B total ww | [104,105] |

| Dengue virus | Flaviviridae | 390 M ww | 96 M ww | 10k ww | $2.1B US, SA | [106,107] |

Globally, since 1981.

Spanish flu of 1918.

30 million outpatient visits.

100-600 thousand hospitalizations.

The death rate is decreasing, from 535,000 deaths in 2000 to 139,300 deaths in 2010.

$10.7 billion in direct medical expenditures in the USA for HCV-related disease from 2010 to 2019.

Cases of microcephaly. K,M,B = thousand, million, billion, ww= worldwide, SA = South America.

Virus diversity can be measured by sequencing virus isolates from different geographical areas. Such investigations are especially informative for RNA viruses that evolve rapidly, resulting in large sequence diversity. In Table 2 , we summarize the 20 most studied virus families as a function of the number of sequenced genomes. Notably, we find more than 7,000 genomes of flaviviridae that include the Zika virus. Furthermore, we count more than 2,000 genomes of retroviridae, including the HIV virus. Sequences of flaviviridae and retroviridae are highly variable, as more than 200,000 sequences in both families cannot be clustered into similar sub-groups. In particular, we applied a similarity threshold of 98% sequence identity with the tool CD-HIT-EST [2], considering genomes with more than 98% sequence identity as a single cluster (Table 2). Cluster representatives are assumed to be the longest sequence in each 98%-similar group. When available, complete genomes from RefSeq viral and neighbor complete genomes [3] are considered cluster representatives.

Table 2.

20 best-studied viruse families (by number of genomes sequenced). Sequence numbers as of July, 2016. Clustered sequenced were clustered at ≥98% sequence identity). U/C = un-/ clustered gives the fold-reduction under clustering, indicating the extent of sequence redundancy among complete genomes. Genome data was retrieved from Genbank.

| Baltimore Class | Family name | Seqs (unclust.) | Disease examples | U/C | Total complete genomes (unclust.) | Complete genomes (clust.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III (dsRNA) | Reoviridae | 65870 | Rare diarrhea | 5.50 | 31945 | 5803 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Flaviviridae | 225112 | Zika | 3.88 | 7837 | 2019 |

| VII (dsRNA-RT) | Hepadnaviridae* | 78558 | Hepatitis | 3.72 | 7248 | 1946 |

| II (ssDNA) | Geminiviridae | 13158 | --- | 2.77 | 6421 | 2316 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Picornaviridae | 85636 | Cold etc | 2.30 | 3447 | 1500 |

| VI (ssRNA-RT) | Retroviridae | 716088 | AIDS etc | 1.37 | 2890 | 2103 |

| II (ssDNA) | Circoviridae | 7838 | --- | 4.99 | 2706 | 542 |

| V (-ssRNA) | Phenuiviridae | 4139 | Rift Valley fever | 4.37 | 1678 | 384 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Coronaviridae | 19164 | SARS | 4.84 | 1549 | 320 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Potyviridae | 16115 | 1.82 | 1536 | 843 | |

| I (dsDNA) | Papillomaviridae | 17847 | Warts, cancer | 3.80 | 1364 | 359 |

| I (dsDNA) | Polyomaviridae | 8604 | Rare cancers | 7.79 | 1277 | 164 |

| V (-ssRNA) | Filoviridae | 2165 | Ebola | 34.03 | 1259 | 37 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Togaviridae | 8924 | Rubella | 9.04 | 1239 | 137 |

| V (-ssRNA) | Pneumoviridae | 22578 | Cold-like | 20.18 | 1231 | 61 |

| II (ssDNA) | Nanoviridae | 3110 | --- | 4.20 | 1183 | 282 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Caliciviridae | 32405 | gastroenteritis | 3.67 | 1072 | 292 |

| V (-ssRNA) | Paramyxoviridae | 29726 | measles | 3.08 | 1008 | 327 |

| IV (+ssRNA) | Bromoviridae | 4677 | (plants) | 1.99 | 764 | 384 |

| V (-ssRNA) | Arenaviridae | 2639 | e.g. Lassa fever | 1.62 | 758 | 469 |

Hepadnaviruses have an RNA intermediate and thus are not strict DNA viruses.

As another aspect of viral variability, humans are infected by a variety of different viruses. For instance, Wylie et al. found that an average of 5.5 viral genera were found in each of 102 healthy individuals [4]. As only five body habitats were screened, including nose, skin, mouth, vagina, and stool, most people likely carry dozens of different viruses. However, only a few lead to clinical symptoms or disease. Furthermore, Poon et al. [5] found numerous variants of Influenza A in individual human hosts. Such variants showed changing abundance over time and between individuals, reflecting their ability to evolve and adapt quickly to changing hosts and conditions.

3. Virus-human host protein-protein interaction databases

During the last decade numerous protein interactions between human viruses and their host cells have been mapped and more thoroughly investigated. Most of these efforts focused on relatively few viruses, such as Hepatitis C virus [[6], [7], [8], [9]], Human Immunodeficiency Virus [10,11], Influenza A virus [12], herpesviruses [13] such as Epstein-Barr Virus [14,15], as well as Dengue [16] and a few others [17]. As a consequence of many high-throughput screens, databases of PPIs have been filled with tens of thousands of virus-human interactions. The IMEx (International Molecular Exchange) consortium of databases has been particularly valuable, as members use a standard format (PSI-MS) for recording meta-data for PPIs [18], including experimental details. IMEx members and observers include, notably, BioGRID [19], DIP [20], IntAct [21] and MINT [22] (Table 3 ). Other generalist PPI databases [23] also collect host-virus interactions but are not further discussed here. Specialized web-based resources have been developed to integrate molecular pathogen-host interactions (PHI) and related data from these PPI databases (generic as well as PHI databases are shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of host-pathogen and other protein-protein interaction databases that provide human-virus protein interactions. PHI-PPIs were drawn from databases shown in bold.

| database | database type | Human viral species | webpage | Physical PPIs* (March, 2018) | Direct PPIs** (March, 2018) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCVPro | PHI | only HCV | http://www.cbrc.kaust.edu.sa/hcvpro/ | 618 | 565 | [24] |

| HIV-1 @NCBI | PHI | only HIV | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/viruses/retroviruses/hiv-1/interactions/ | 6,824 | 1,594 | [26] |

| PHIDIAS | PHI | 37 | http://www.phidias.us | *** | *** | [29] |

| PHISTO | PHI | **** | http://www.phisto.org | **** | **** | [108] |

| HPIDB | PHI | 43 | http://www.agbase.msstate.edu/hpi/main.html | 19,681 | 10,628 | [28] |

| VirHostNet | PHI | 106 | http://virhostnet.prabi.fr | 20,674 | 14,013 | [25] |

| VirusMentha | PHI | 98 | http://virusmentha.uniroma2.it | 10,692 | 5,863 | [27] |

| DenHunt | PHI | 1 | http://proline.biochem.iisc.ernet.in/DenHunt/) | 1,064 | 682 | [109] |

| DenvInt | PHI | 1 | https://denvint.000webhostapp.com | 784 | 784 | [65] |

| BioGRID | PPI | 13 | https://thebiogrid.org/ | 2,427 | 1,936 | [19] |

| DIP | PPI | 48 | http://dip.mbi.ucla.edu/dip/ | 519 | 430 | [20] |

| IntAct | PPI | 142 | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/ | 14,282 | 5,934 | [21] |

| MINT | PPI | 67 | https://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/ | 6,400 | 2,530 | [22] |

“Physical PPIs” refers to PPIs for which there is experimental evidence of a physical interaction, but absence of evidence for a direct interaction using PSI-MS controlled vocabularies.

“Direct PPIs” refers to PPIs for which there is experimental evidence of a physical, direct interaction using PSI-MS controlled vocabularies.

PPI information and evidence requires manual extraction or text-mining.

The PHISTO website was unavailable for the duration of the writing of this review.

Some PHI databases specialize on only one specific pathogen species such as HCVpro [24]. A wider range of human specific viruses are covered by VirHostNet [25] and others (Table 3).

The differences between databases often exacerbate the comparison of their data. Especially the lack of experimental details may obscure the nature of an interaction as direct or “indirect”, e.g. when a protein is co-purified with other proteins without additional evidence whether it is directly binding to specific members of such a complex. For instance, out of the over 17,000 HIV-1 – human PPIs reported in HIV-1db [26] as of August, 2017, fewer than 7,000 are physical interactions, and the number of direct (rather than “complexed”) interactions is unclear. While clear evidence of direct physical interaction is provided for some PPIs (e.g. “binds”, “phosphorylates”, “cleaves”), the evidence is weaker for others. Compared to PSI-MS standards, these evidence descriptors were generally more ambiguous. Using a strict set of criteria, the number of physical and direct PPIs between HIV-1 and human proteins is about 1,600. Out of the additional ∼ 5,400 physical interactions, the majority have neither evidence for nor against a direct interaction (e.g. “interacts with”, “stabilizes”, “recruits”). While NCBI’s HIV-1DB is an invaluable resource for HIV-1 researchers, “mining” physical PPIs from the entire database confidently without manual inspection or natural language processing can be difficult.

PHI databases that cover a wide range of viruses and hosts include VirHostNet [25], VirusMentha [27] and HPIDB [28] (Table 3). In addition to data storage, VirusMentha and PHIDIAS [29] offer certain visualization and analysis tools. In addition, PHI databases may contain interactions that are not present in generalist PPI databases as a result of exhaustive mining of pathogen-specific data and literature. The most recent update of VirHostNet contains nearly 22,000 virus-human PPIs, of which 14,000 are direct. However, this diversity of source data does present some drawbacks. Many PHI databases lack a standard (i.e. PSI-MS) format (except HPIDB), making inference about the molecular details of interactions such as evidence codes challenging. Furthermore, filtering criteria for collecting virus-host PPIs are often difficult or impossible to ascertain. Finally, the update cycles can be irregular, and often the underlying pipelines for collecting data change from one version to the next. Generally, host-virus protein interaction data in the above PHI databases are integrated mainly from more general PPI databases using automatic integration tools such as PSICQUIC [30] and by manual literature curation. Hence, we excluded PHI databases that do not follow PSI-MS standards from a deeper analysis.

We collected protein interactions for a variety of viral families using the databases in Table 3 (shown in bold) and from general databases such as BioGRID and IntAct. Not surprisingly, our understanding of human-virus PPIs is highly biased towards a few well-studied viruses. For instance, only 5 viruses have more than 1,000 physical interactions, such as Influenza A with 3,746, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) with 3,163, HIV-1 with 2,540, Herpesvirus 8 with 1,643, and Hepatitis C with 1,082. Notably, Influenza, HIV and Hepatitis viruses were among the most economic burdensome pathogens (Table 1). The human papilloma viruses totaled 4,645 interactions across 29 different species. Evidence for direct interactions of these top viruses varied, but was notably high for herpesvirus 8 (1,623 direct /1,643 physical) and HIV-1 (2,365 direct /2,540 physical). Considering whole virus families (Table 4 ), we found a total of 5,957 physical interactions with human host proteins involving proteins of orthomyxoviridae. As indicated previously, such sets of interactions are often dominated by a single virus. In addition, we obtained 462 interactions for virus families with fewer than 100 PPIs. In Fig. 1 , we summarized the sets of human proteins that were targeted by different virus families and their substantial overlap. While these numbers are roughly similar, the corresponding virus families represent vastly different genome sizes and virus diversity. For instance, HIV encodes only about 10 proteins with more than 100 interactions per virus protein. EBV, by comparison, encodes about 85 proteins leading to “only” 20 interactions per virus protein on average. On a more quantitative level, the number of interactions between proteins of the human host and viruses that belong to a certain family correlate significantly with the presence of different genomes in a given virus family (Fig. 2 ). Before we can even begin to interpret these interactions, we need to ask if it is biologically meaningful or even possible if a virus protein has >100 interactions (see below).

Table 4.

Number of host-virus protein-protein interactions of major human virus families. Interaction numbers are pooled from BioGRID, DIP, HPIDB, IntAct, MINT.

| viral family | # virus-human PPIs (physical / direct) | representative virus-human PPIs (physical / direct) |

|---|---|---|

| Herpesviridae | 5957/3570 | Herpesvirus 4 / Epstein-Barr (3,163/1,049); Herpesvirus 8 (1,643/1,623) |

| Papillomaviridae | 4645 | Papillomavirus types 1a,3,5,6,6b,8,9,11,16,18,32,33,39 (4,275/2,649) |

| Orthomyxoviridae | 3748/953 | Influenza A (3,746/952) |

| Retroviridae | 2998 | HIV-1 (2,540/2,365); Primate T-lymphotropic Virus 1 (254/240) |

| Flaviviridae | 1475 | Hepatitis C (1,082/802); Dengue (535/535) |

| Paramyxoviridae | 665 | measles (481/445); Nipah Henipavirus (133/2) |

| Adenoviridae | 451 | Adenovirus types 2,5,12 (378/211) |

| Pneumoviridae | 270 | Respiratory Synctial Virus A2 (262/258) |

| Poxviridae | 247 | Vaccinia virus (190/47); Variola virus (18/18) |

| Filoviridae | 177 | Ebola virus (154/11); Marburg virus (23/0) |

| Polyomaviridae | 165 | Macaca Mulatta Polyomavirus 1 (79/65); JC Polyomavirus (41/1); Human Polyomavirus 1 (39/0) |

| Hepadnaviridae | 128 | Hepatitis B (127/111) |

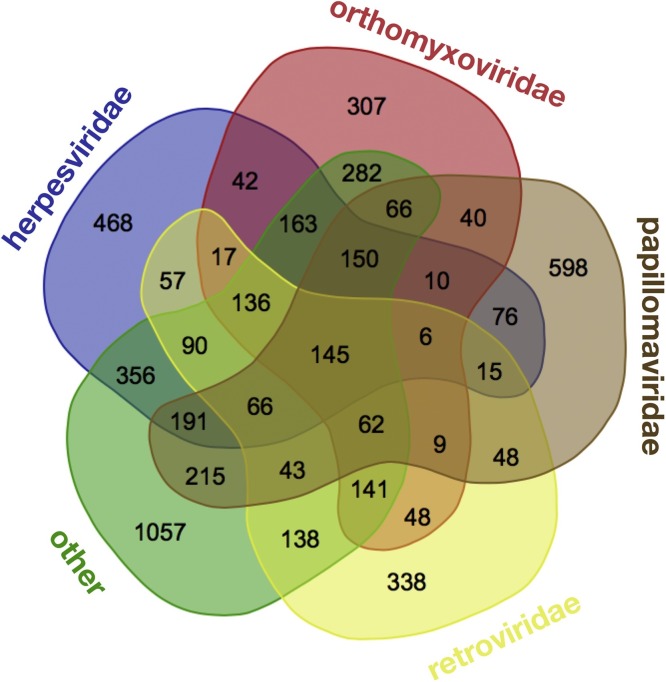

Fig. 1.

Human proteins targeted by different virus families. The number of targets is based on all available interactions between viral and human host proteins, including 1,988 targets of Herpesviridae, 1,624 of Orthomyxoviridae, 1,740 of Papillomaviridae, 1,359 of Retroviridae and a pool of 3,301 targets of other virus families. Only a limited number of human proteins is targeted by many different virus families.

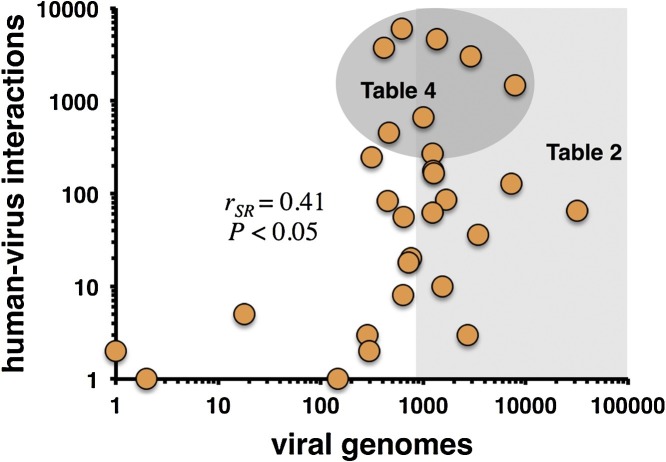

Fig. 2.

Known human-virus interactions and sequenced viral genomes of virus families. In particular, the number of sequenced genomes of different virus families correlates with the number of known interactions between proteins of the family specific viruses and the human host (Spearman rank correlation coefficient rSR = 0.41, P < 0.05). Furthermore, we labeled data points that correspond to virus families in Table 2, Table 4.

4. How reliable are published virus-host interactions?

The large number of PPIs and other high-throughput data raise the question about the reliability of these datasets. We address this problem by examining the reliability of different methods and then ask how many interactions are biologically relevant.

Both yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) and affinity purification coupled to mass spectrometry (AP/MS) approaches have limitations that lead to a significant number of false negatives and false positives [[31], [32], [33]]. While genetic screens using RNA interference (RNAi) or other methods suffer from the same burden (see below) we will discuss these issues in the context of virus-host interactions.

The reliability of PPIs is indicated by the specific evidence for either direct physical or indirect interaction. For instance, Y2H assays usually yield direct interactions while co-purifications (AP/MS) typically provide indirect interactions, especially when large complexes are studied. Note, that co-purification studies provide direct interactions when only 2 proteins are present in a complex. Around 50% of all virus-human PPIs may be indirect (Table 3, bold). While most available virus-host PPIs are physical, it may not be known whether the interaction is direct or indirect. Databases that are based on the PSI-MS format provide experimental methodology information. Of the databases we used, the proportion of interactions that could be inferred as direct ranged from roughly 50% (IntAct, MINT) to around 70% (BioGRID, DIP).

Furthermore, the reliability of the experimental techniques for detecting direct interactions also needs to be considered. Only a few studies exist that systematically validated human-virus interactions for their biochemical or even physiological validity. Among the first attempts to validate human virus-host interactions was our study of interactions between proteins of the human host and the Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) [34]. In particular, we predicted 20 interactions between 8 KSHV and 20 human proteins from experimentally determined homologous interactions in yeast, worm, and fly. Nineteen of these 20 virus-host interactions were tested by CoIP, and an unexpectedly large percentage of interactions (13 out of 19, or 68%) was confirmed.

In another study, Zhang et al. found 109 interactions between 33 Vaccinia and ∼160 human proteins of which 27 were tested by GST pull-downs [35]. 17 of these were confirmed, translating to a 63% validation rate. While these numbers appear to be rather high, only certain subsets were selected, putatively representing a biased validation rate of a complete Y2H data set.

Khadka et al. [16] screened all 10 proteins of Dengue virus against a human liver Y2H library and found 139 interactions involving 8 Dengue and 105 human proteins. 33 interactions were detected by two or more Dengue protein fragments. 16 out of 23 tested interactions were also confirmed by an independent split-luciferase assay. 23 human genes were tested by siRNA assays for their effect on viral replication, and 12 of them were found to be required for Dengue replication. Interestingly, over 40% of the human proteins reported in this study to interact with proteins of the Dengue virus have been implicated in the life cycles of at least one other virus, with the greatest overlap with proteins linked to HCV infection.

In a similar study, 95 human proteins were identified in yeast two-hybrid screens with Influenza virus (INFV), and all were tested for their effects on INFV replication in similar siRNA experiments [12]. Of these, three were required for INFV replication and eight exerted a negative effect, for a total of 11 (12%) proteins that affected INFV replication [12]. Similarly, in large-scale siRNA screens for host factors affecting viral replication, the average hit rate was 1% [36,37].

Jäger et al. used AP-MS to identify approximately 2,500 human proteins forming more than 10,000 physical interactions with the ∼10 HIV proteins analyzed [11]. However, they rigorously filtered their interaction data to obtain a “core” data set of 497 PPIs. Such a set was then compared to literature-curated PPIs in VirusMint [38], that were mostly derived from small-scale targeted studies. Notably, the overlap was only 19 interactions. As another control, Jäger et al. also carried out their purifications in two different cell lines, HEK293 and Jurkat, yet only 196 out of 497 interactions were found in both (39%). Finally, Jäger et al. compared their interaction data with four published RNAi screens [36,[39], [40], [41]] that found a total of 1,071 human genes, of which only 55 overlapped with the 435 proteins found by AP/MS. In a follow-up study, Emig-Agius et al. [42] identified a set of 554 human proteins with “close proximity” to HIV proteins in both AP/MS data and RNAi screens. That is, 382 were direct HIV interactors identified by AP-MS, 79 were identified directly by RNAi, and 148 were novel predictions identified by proximity in the interaction network. These 554 human proteins were also enriched for 40 protein complexes from the CORUM database of human protein complexes [43]. Out of these 40 complexes, 27 had not been reported in previous studies of HIV, while the remaining 13 complexes had been identified by at least one previously published analysis. Furthermore, 36 of the 40 complexes in the map had at least one subunit that directly interacted with HIV. As a result they found three protein complexes which had not been identified in previous analyses. Additional RNAi experiments confirmed that some subunits were required for efficient HIV infection.

Such examples demonstrate that many human proteins have been identified that are involved in virus infection and physically interact with virus proteins. However, there is little reproducibility even with RNAi screens that have identified human genes required for infection. For instance, a comparison of the first three screens for human proteins involved in HIV infection [36,41,44] revealed only three genes that were identified by all screens.

5. How many interactions does a virus require?

The sheer number of host-virus interactions that have been found for many viruses may suggest that we have identified most if not all interactions. As indicated above, we know from other studies that interaction screens likely contain a large number of false positives. While viral proteins are highly enriched for disordered regions that are known to favor interactions with many partners [45], the question remains as to how many interactions does a virus realistically utilize to infect its host? How do we identify the physiological interactions among those that have been found overall? Unfortunately, such estimates currently do not exist, especially if we assume that viruses of similar proteome size may use similar numbers of PPIs. While it is hard to estimate such numbers for human viruses, bacteriophages may serve as a simpler model: 50 years of research have identified about 30 host-virus interactions between E. coli and phage lambda, which encode ∼4,000 and 73 proteins, respectively [46]. Assuming that most (physiologically relevant) host-virus interactions in this system have been identified, a large-scale analysis of E. coli-lambda interactions revealed 62 interactions in a high-confidence set [47]. However, of the 62 high-confidence PPIs only two were previously known to be physiological, while the role of the other 60 remains unknown. Such observations may indicate that up to 97% of these PPIs are false positives. However, lambda is unusual as compared to other phage in that many lambda proteins are processed during maturation and thus interactions are more difficult to detect. Protein processing seems to be less common among other phages, such as T7, whose 55 proteins are known to be involved in only 15 interactions with its host [46]. For T7 and lambda about 30–40 interactions have been found between their virion proteins, which are easier to detect and possibly more abundant than in human viruses, given the more elaborate virus structure in these tailed phage when compared to the often simple-structured human viruses. Although lambda and T7 may not be the most meaningful references for human viruses they give us a sense for the complexity of the problem. Interestingly, human viruses include many cases with substantial proteolytic processing, such as Hepatitis C Virus, in which a polyprotein prevents many interactions that are found when the proteolytic fragments are used for interaction screens [48].

6. What are the protein targets of human viruses?

The investigation of different host-virus protein interaction networks revealed functional classes of host proteins that different viruses commonly target. In particular, viruses prefer human host proteins that were involved in cell cycle regulation, signaling, nuclear transport and cell trafficking as well as transcription and translation functions [6,14,34,49,50]. However, different types of viruses will target different human proteins, reminding us that each viral family uses a different strategy to invade a human host cell [51,52].

The abundance of virus-host interaction data prompted topological analysis of networks. For instance, Navratil et al. described a human infectome network (HIN) that linked 416 viral proteins to 1,148 human proteins through 2,099 manually curated virus-host PPIs [53]. In fact, 32% of these cellular proteins are targeted by more than one virus protein of the same virus. A similar fraction, 28% of these cellular targets interact with proteins from more than one virus.

Clearly, virus proteins target a relatively select number of human proteins that are relevant for their replication. These human targets appear to be highly connected: the mean degree of these targets was 38 vs. 10 in non-targeted proteins [53]. Even among highly connected proteins (degree k>5) in the human interactome, the degree of virus targets was twice as large as those of non-targeted proteins. Independent analyses found that viral proteins preferably target human host proteins that are involved in a large number of interactions [14,49,50,[54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]]. As the number of interactions is a local measure of centrality, other more global measures of centrality were considered as well. In particular, betweenness centrality measures how many connections go through a particular protein in a network when proteins were mutually connected through their shortest paths. Indeed, various viruses target human host proteins with high betweenness centrality. As a corollary, such central proteins also have significantly shorter paths to other proteins [14,49,50,[54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]], as well as participate in a higher number of pathways and protein complexes [61]. Furthermore, topological analyses of revealed that human host proteins that were targeted by viruses are strongly connected among each other [61]. Recently, the focus of modern network research has shifted to the determination of nodes that allow the topological control of a network [62,63]. Such controlling nodes need to be tweaked to exert the behavior of the remaining nodes in the underlying network. Notably, such controlling genes were enriched with essential genes and disease genes, and they appeared in regulatory interactions [64,65]. Furthermore, they also played a role as targeted and required genes of viral infections [66,67]. As a consequence, such centrality measures and the determination of control nodes may allow the computational prediction of potential viral targets based on topological measures [57,58,[68], [69], [70]].

7. Do different virus strains have different interaction patterns?

As discussed above, viruses evolve quickly, and often hundreds if not thousands of strains have been sequenced, suggesting that their diversity may affect their interaction patterns. While several studies have addressed this question, we illustrate the idea with a study of human papilloma viruses (HPV). Neveu et al. [71] tested the interactions of two HPV proteins, E6 and E7, derived from 11 different strains each against 94 and 88 human target proteins, respectively. Each protein often had surprisingly different interaction profiles, depending on the strain from which they were derived. For instance, the affinity of different E6 proteins from different strains for their cellular targets Smad2 and Smad3 differed by more than 10-fold (as measured by an in vitro luciferase protein complementation assay). Interestingly, these authors also showed that the target proteins had very distinct tissue-specific expression profiles, partly explaining the tissue specificity of these viruses. In a complementary study, Gulbahce et al. [72] also investigated the E6 and E7 proteins but focused on the effect these proteins had on the expression levels in different target cells. Both proteins interacted with different proteins but also affected the expression of very different target proteins in human fibroblast and keratinocytes, emphasizing the complexities that arise when virus variation and human cell types are combined.

8. How are protein-protein interactions related to viruses with multiple hosts?

Most viruses are capable of infecting multiple hosts, at least closely related host species. However, some viruses infect quite distantly related species, such as human and bird influenza. One might expect that such “generalist” viruses enjoy an evolutionary advantage due to their potential to infect more hosts. However, in most cases adaptive mutations for one host bring about a decrease in fitness for replicating within another host, with a possible exception when a host’s population tends to fluctuate widely [73]. Most viruses require only one host although some viruses (notably arboviruses such as dengue) use humans and other animals as “dead-end” hosts that do not transmit the virus to others in the population [74]. For obligate multi-host viruses, a phenotype specific to each host is often developed, which increases the chances of transmission. The hosts themselves are often very different, in terms of pH, temperature, and cell type. Thus, it is likely that PPIs from obligate multi-host viruses are more diverse than PPIs from optional multi-host viruses.

Arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses) are among the most burdensome multi-host viruses for humans. As the dengue virus is a good example the DenvInt database [75] catalogues interactions between 10 dengue proteins and both human and mosquito proteins. The dengue-human network consists of 535 interactions between 10 dengue and 335 human proteins, while the dengue-mosquito network consists of 249 interactions between 10 dengue and 140 mosquito proteins.

Even with extensive recombination, as observed among the “chromosomes” of influenza viruses, many viruses are known to jump from animals to humans [76,77], often leading to unusually severe outbreaks. The host environments do not vary as widely for viruses such as influenza A compared to arboviruses. Therefore, host-virus protein interactions PPIs may be more similar. Crossover mutations in influenza viruses occur predominantly in two proteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, which allow for entry and exit, respectively.

Using the virus-human PPIs from the databases in Table 3, the extent of multi-host interactions appears much larger, although their physiological relevance is difficult to determine. In particular, we found 71 human viruses from 15 different viral families in Table 4 (except filoviridae and polyomaviridae) that had interactions with 43 non-human hosts. The most common alternate hosts were simian, avian, mouse, cow and pig. There were over 100 interactions between the 2006 h5n1 pandemic flu strain and chicken. However, there were even some interactions with bacterial and plant hosts (for herpesviral proteins). In all, there were 434 physical interactions, of which 186 were direct. Conversely, non-human viruses were also found to have PPIs with human proteins, with less diversity but overall higher interactions. These 39 non-human viruses were from 15 different viral families, of which only 7 were present in Table 4. 627 physical and 525 direct PPIs were found. This greater number of PPIs may be a result of the larger human proteome compared to most alternative hosts. The non-human hosts were similar in both directions of the analysis. However, some differences could be found. Canine viruses were found to have interactions in human, although human viruses were not found to have interactions in canine species. On the other hand, non-human viruses did not come from any bacterial or plant hosts.

9. The virus interactome-diseasome connection

It has been long known that some viruses are involved in diseases not typically associated with infection. For instance, up to 20% of cancers may be caused by viruses such as papilloma or certain herpesviruses [78]. Navratil et al. [53] used a set of virus targets that was compared to a list of 1,729 human genetic disease-related proteins as of the OMIM database [79]. Notably, 13% of human virus targets were also associated with at least one human disease [53], indicating that a human protein interacting with a virus protein is twice as likely to be involved in a disease than a non-target. Most of the diseases found in this study were related to cancer or neurodegenerative diseases. Surprisingly, type-1 diabetes was also associated with virus infection, as were autoimmune diseases in general, as many virus infections elicit a strong immune reaction.

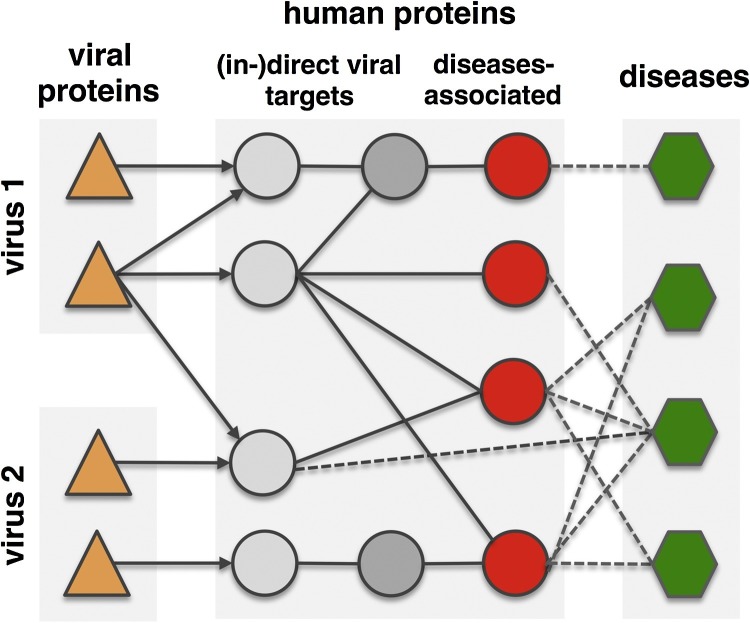

Obtaining a similar conclusion, Gulbahce et al. analyzed the connection between Epstein-Barr-Virus (EBV), human papilloma virus (HPV) and disease [72]. However, these authors not just used protein interactions but also metabolic networks and regulatory interactions (Fig. 3 ). Using U.S. Medicare patient medical history data derived from 13 million patients, Gulbahce et al. found that many diseases were often associated with infections of the underlying viruses. For instance, patients that suffered from an infection with the human papilloma virus had 15.7 and 2.7 times increased chance of developing retina and bladder cancer and a higher risk of Fanconi anemia [72]. Furthermore, Rozenblatt-Rosen et al. [80] experimentally showed that genomic variations and tumor viruses may cause cancer through related mechanisms. In particular, their systematic analyses of viral host targets identified cancer genes with a success rate that was similar compared to functional genomics and determination of tumor mutations.

Fig. 3.

The interactome-diseasome connection. Topological proximity between viral targets and genes associated with virally implicated diseases. Many diseases are directly or indirectly connected to virus proteins and their human targets. Modified after [72].

10. Virus interactions with the host metabolome

Evidence is mounting that viruses not just highjack host replicative functions, but also the host metabolic machinery. For instance, Adenovirus 5 proteins E4ORF1 and E4ORF6 co-immunoprecipitate with MYC in the nucleus, probably by directly interacting with the cancer protein MYC. While MYC has diverse effects on numerous target genes that it regulates, E4ORF1 induces MYC to activate a subset of glycolytic targets (viruses with a deletion of the E4 protein are defective for inducing glycolysis). Thai et al. [81] conclusively demonstrated that adenovirus induced glycolysis generates metabolites for increased nucleotide biosynthesis in infected cells. Furthermore, Ramière et al. determined a direct interaction between the NS5A of the Hepatitis C virus and cellular hexokinase 2 through protein complementation assays and co-immunoprecipitation. Notably, NS5A expression was sufficient to enhance glucose consumption and lactate secretion. Indicating a direct point of influence on a hosts metabolism through a host-virus protein interaction, viruses putatively manipulate host metabolism to generate more nucleotides and other compounds that are needed for their replication [82]. However, in most host-virus system viral points of metabolic intervention are understudied, and ambiguity remains whether interactions of virus proteins with host enzymes directly or indirectly reprogram metabolism.

11. Conclusions and outlook

Protein-protein interactions are at the core of any virus infection. As a consequence, detailed knowledge of such interactions is critical for our understanding of viral diseases and the development of new drugs. However, knowledge about interactions between host and viral proteins is strongly biased toward a small number of viral families. Notably, these families often have diverse genomes while being of utmost biomedical and economic importance. In turn, for many viruses of lesser medical importance only few interactions are known that are not sufficient to understand their infection mechanisms at this point. Notably, viruses evolve much quicker than their hosts, especially in RNA viruses, not the least because they can produce numerous (variant) virus particles by the time the host can mount an immune response. Thus, viruses can also adapt their host-virus interaction interface faster than a host population can react by mutating its target proteins, although an individual immune system is usually able to fight off an infection [83].

Despite the abundance of known interactions between human and viral proteins, current host-pathogen interaction databases lack the level of specific annotations compared to general protein interaction databases. Furthermore, the level of reliability of host-virus interactions is currently not on par with their intra-species counterparts. As we surmise that host-virus protein interactions are key to our understanding of virus infection and disease, currently known host-virus protein interactions may suggest plausible hypotheses. However, precise mechanisms remain often elusive as the majority of host-virus protein interactions remain to be validated.

While the determination of host-virus protein interaction interfaces is continuing, new frontiers are rapidly emerging. In particular, the availability of host-virus interactions raises the questions of viral co-infections that are reflected by interactions between host and variable viral proteins at the same time. Current knowledge about such co-infections can be inferred from known interactions that have been found from separate analyses that focused on a single host-virus system. However, such interactions will need to be determined in experimental settings that account for the presence of different pathogens. Such settings will allow the assessment of synergies and interactions between pathogens that putatively have a physiological effect on the host as well as only appear as a consequence of a co-infection. The relationships between diseases that are triggered by host-virus protein interactions and other non-viral comorbidities are increasingly investigated. As a corollary of the previous point, knowledge about such systems is mostly based on assembling and analyzing interaction interfaces that were found independently from the presence of other diseases as well. As a consequence, host-virus interaction interfaces may change in the presence of other diseases. In turn, host-virus interactions may facilitate the emergence of comorbidities, suggesting that host-virus interaction interfaces need to be experimentally assessed in the presence of associated diseases.

While current host-virus interaction interfaces almost entirely focus on interactions between proteins, the impact of viral proteins on enzymes and the human metabolome have hardly been investigated. As a corollary, microbiome studies will identify many more viruses in humans. In the course of these studies, we will also find many more commensal viruses which do interact with their human host but may actually be beneficial, and potentially even help us to fight other pathogens and parasites.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Xue K.S., Greninger A.L., Perez-Osorio A., Bloom J.D. Cooperating H3N2 influenza virus variants are not detectable in primary clinical samples. mSphere. 2018;3(1) doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00552-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W., Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brister J.R. Virus variation resource–recent updates and future directions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D660–D665. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wylie K.M. Metagenomic analysis of double-stranded DNA viruses in healthy adults. BMC Biol. 2014;12:71. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0071-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poon L.L. Quantifying influenza virus diversity and transmission in humans. Nat. Genet. 2016;48(2):195–200. doi: 10.1038/ng.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Chassey B. Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:230. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tripathi L.P. Network based analysis of hepatitis C virus core and NS4B protein interactions. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6(12):2539–2553. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan P.T. Identification and comparative analysis of hepatitis C virus-host cell protein interactions. Mol. Biosyst. 2013;9(12):3199–3209. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70343f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngo H.T., Pham L.V., Kim J.W., Lim Y.S., Hwang S.B. Modulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 3 by hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Virol. 2013;87(10):5718–5731. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03353-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gautier V.W. In vitro nuclear interactome of the HIV-1 Tat protein. Retrovirology. 2009;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jager S. Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature. 2011;481(7381):365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapira S.D. A physical and regulatory map of host-influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 2009;139(7):1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fossum E. Evolutionarily conserved herpesviral protein interaction networks. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(9):e1000570. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calderwood M.A. Epstein-Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(18):7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsman A., Ruetschi U., Ekholm J., Rymo L. Identification of intracellular proteins associated with the EBV-encoded nuclear antigen 5 using an efficient TAP procedure and FT-ICR mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7(6):2309–2319. doi: 10.1021/pr700769e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khadka S. A physical interaction network of dengue virus and human proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011;10(12) doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012187. M111 012187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pichlmair A. Viral immune modulators perturb the human molecular network by common and unique strategies. Nature. 2012;487(7408):486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature11289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchard S. Protein interaction data curation: the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) consortium. Nat. Methods. 2012;9(4):345–350. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatr-Aryamontri A. The BioGRID interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D816–D823. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salwinski L. The database of interacting proteins: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D449–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orchard S. The MIntAct project--IntAct as a common curation platform for 11 molecular interaction databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D358–D363. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Licata L. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D857–D861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szklarczyk D., Jensen L.J. Protein-protein interaction databases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1278:39–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2425-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwofie S.K., Schaefer U., Sundararajan V.S., Bajic V.B., Christoffels A. HCVpro: hepatitis C virus protein interaction database. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11(8):1971–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guirimand T., Delmotte S., Navratil V. VirHostNet 2.0: surfing on the web of virus/host molecular interactions data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D583–D587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ako-Adjei D. HIV-1, human interaction database: current status and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D566–D570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calderone A., Licata L., Cesareni G. VirusMentha: a new resource for virus-host protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D588–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar R., Nanduri B. HPIDB--a unified resource for host-pathogen interactions. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11(Suppl. 6):S16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S6-S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang Z., Tian Y., He Y. PHIDIAS: a pathogen-host interaction data integration and analysis system. Genome Biol. 2007;8(7):R150. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aranda B. PSICQUIC and PSISCORE: accessing and scoring molecular interactions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8(7):528–529. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y.C., Rajagopala S.V., Stellberger T., Uetz P. Exhaustive benchmarking of the yeast two-hybrid system. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(9):667–668. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0910-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Titz B., Schlesner M., Uetz P. What do we learn from high-throughput protein interaction data? Expert Rev. Proteom. 2004;1(1):111–121. doi: 10.1586/14789450.1.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkatesan K. An empirical framework for binary interactome mapping. Nat. Methods. 2009;6(1):83–90. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uetz P. Herpesviral protein networks and their interaction with the human proteome. Science. 2006;311(5758):239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1116804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L. Analysis of vaccinia virus-host protein-protein interactions: validations of yeast two-hybrid screenings. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8(9):4311–4318. doi: 10.1021/pr900491n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brass A.L. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319(5865):921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brass A.L. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139(7):1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatr-aryamontri A. VirusMINT: a viral protein interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D669–D673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konig R. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeung M.L., Houzet L., Yedavalli V.S., Jeang K.T. A genome-wide short hairpin RNA screening of jurkat T-cells for human proteins contributing to productive HIV-1 replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(29):19463–19473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H. Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell. Host Microbe. 2008;4(5):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emig-Agius D. An integrated map of HIV-human protein complexes that facilitate viral infection. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruepp A. CORUM: the comprehensive resource of mammalian protein complexes--2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D497–D501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konig R. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463(7282):813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tokuriki N., Oldfield C.J., Uversky V.N., Berezovsky I.N., Tawfik D.S. Do viral proteins possess unique biophysical features? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34(2):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hauser R. Bacteriophage protein-protein interactions. Adv. Virus Res. 2012;83:219–298. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394438-2.00006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blasche S., Wuchty S., Rajagopala S.V., Uetz P. The protein interaction network of bacteriophage lambda with its host, Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 2013;87(23):12745–12755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02495-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flajolet M. A genomic approach of the hepatitis C virus generates a protein interaction map. Gene. 2000;242(1–2):369–379. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dyer M.D., Murali T.M., Sobral B.W. The landscape of human proteins interacting with viruses and other pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(2):e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wuchty S., Siwo G., Ferdig M.T. Viral organization of human proteins. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e11796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brito A.F., Pinney J.W. Protein-Protein interactions in virus-host systems. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1557. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dix A., Vlaic S., Guthke R., Linde J. Use of systems biology to decipher host-pathogen interaction networks and predict biomarkers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22(7):600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Navratil V., de Chassey B., Combe C.R., Lotteau V. When the human viral infectome and diseasome networks collide: towards a systems biology platform for the aetiology of human diseases. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durmus Tekir S.D., Uelgen K. Systems biology of pathogen-host interaction: networks of protein-protein interaction within pathogens and pathogen-human interactions in the post-genomic era. Biotechn. J. 2013;8(1):85–96. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arnold R., Boonen K., Sun M.G., Kim P.M. Computational analysis of interactomes: current and future perspectives for bioinformatics approaches to model the host-pathogen interaction space. Methods. 2012;57(4):508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korth M.J., Tchitchek N., Benecke A.G., Katze M.G. Systems approaches to influenza-virus host interactions and the pathogenesis of highly virulent and pandemic viruses. Semin. Immunol. 2013;25(3):228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nourani E., Khunjush F., Durmus S. Computational approaches for prediction of pathogen-host protein-protein interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:94. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dyer M.D., Murali T.M., Sobral B.W. Supervised learning and prediction of physical interactions between human and HIV proteins. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11(5):917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Durmus Tekir S., Cakir T., Ulgen K.O. Infection strategies of bacterial and viral pathogens through pathogen-human protein-protein interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:46. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halehalli R.R., Nagarajaram H.A. Molecular principles of human virus protein-protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(7):1025–1033. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mariano R., Khuri S., Uetz P., Wuchty S. Local action with global impact: highly similar infection patterns of human viruses and bacteriophages. mSystems. 2016;1(2) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00030-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishitsuka M., Akutsu T., Nacher J.C. Critical controllability in proteome-wide protein interaction network integrating transcriptome. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23541. doi: 10.1038/srep23541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nacher J.C., Akutsu T. Analysis of critical and redundant nodes in controlling directed and undirected complex networks using dominating sets. J. Compl. Networks. 2014;2(4):394–412. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wuchty S. Controllability in protein interaction networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111(19):7156–7160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311231111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khuri S., Wuchty S. Essentiality and centrality in protein interaction networks revisited. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16:109. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wuchty S., Boltz T., Kucuk-McGinty H. Links between critical proteins drive the controllability of protein interaction networks. Proteomics. 2017;17(10):1–11. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201700056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vinayagam A. Controllability analysis of the directed human protein interaction network identifies disease genes and drug targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113(18):4976–4981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603992113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mariano R., Wuchty S. Structure-based prediction of host-pathogen protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;44:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murali T.M., Dyer M.D., Badger D., Tyler B.M., Katze M.G. Network-based prediction and analysis of HIV dependency factors. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7(9):e1002164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tastan O., Qi Y., Carbonell J.G., Klein-Seetharaman J. Prediction of interactions between HIV-1 and human proteins by information integration. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2009:516–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Neveu G. Comparative analysis of virus-host interactomes with a mammalian high-throughput protein complementation assay based on Gaussia princeps luciferase. Methods. 2012;58(4):349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gulbahce N. Viral perturbations of host networks reflect disease etiology. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8(6):e1002531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elena S.F., Agudelo-Romero P., Lalic J. The evolution of viruses in multi-host fitness landscapes. Open Virol. J. 2009;3:1–6. doi: 10.2174/1874357900903010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weaver S.C., Barrett A.D. Transmission cycles, host range, evolution and emergence of arboviral disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2(10):789–801. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dey L., Mukhopadhyay A. DenvInt: a database of protein-protein interactions between dengue virus and its hosts. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11(10):e0005879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mandl J.N. Reservoir host immune responses to emerging zoonotic viruses. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vijaykrishna D., Mukerji R., Smith G.J. RNA virus reassortment: an evolutionary mechanism for host jumps and immune evasion. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(7):e1004902. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morales-Sanchez A., Fuentes-Panana E.M. Human viruses and cancer. Viruses. 2014;6(10):4047–4079. doi: 10.3390/v6104047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McKusick V.A. Mendelian inheritance in man and its online version, OMIM. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80(4):588–604. doi: 10.1086/514346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rozenblatt-Rosen O. Interpreting cancer genomes using systematic host network perturbations by tumour virus proteins. Nature. 2012;487(7408):491–495. doi: 10.1038/nature11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thai M. Adenovirus E4ORF1-induced MYC activation promotes host cell anabolic glucose metabolism and virus replication. Cell. Metab. 2014;19(4):694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miyake-Stoner S.J., O’Shea C.C. Metabolism goes viral. Cell. Metab. 2014;19(4):549–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Christiaansen A., Varga S.M., Spencer J.V. Viral manipulation of the host immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015;36:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Boppana S.B., Fowler K.B. Persistence in the population: epidemiology and transmisson. In: Arvin A., Campadelli-Fiume G., Mocarski E., Moore P.S., Roizman B., Whitley R., Yamanishi K., editors. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Burrel S. Ancient recombination events between human Herpes simplex viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34(7):1713–1721. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johnston C., Gottlieb S.L., Wald A. Status of vaccine research and development of vaccines for herpes simplex virus. Vaccine. 2016;34(26):2948–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Looker K.J. Global and regional estimates of prevalent and incident Herpes simplex virus type 1 infections in 2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Szucs T.D., Berger K., Fisman D.N., Harbarth S. The estimated economic burden of genital herpes in the United States. An analysis using two costing approaches. BMC Infect. Dis. 2001;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Menzies N.A. The cost of providing comprehensive HIV treatment in PEPFAR-supported programs. AIDS. 2011;25(14):1753–1760. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283463eec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnson N.P., Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic. Bull. Hist. Med. 2002;76(1):105–115. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Merson M.H., O’Malley J., Serwadda D., Apisuk C. The history and challenge of HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):475–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Molinari N.A. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25(27):5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patel M.K. Progress toward regional measles elimination - worldwide, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2016;65(44):1228–1233. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wong J.B., McQuillan G.M., McHutchison J.G., Poynard T. Estimating future hepatitis C morbidity, mortality, and costs in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90(10):1562–1569. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang H., Collaborators GBoD Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maynard J.E. Hepatitis B: global importance and need for control. Vaccine. 1990;8 doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90209-5. Suppl:S18-20; discussion S21-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ott J.J., Stevens G.A., Groeger J., Wiersma S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keshavarz K. Economic burden of hepatitis B virus-related diseases: evidence from iran. Hepat. Mon. 2015;15(4):e25854. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.15(4)2015.25854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fischer M. 2016. Zika Virus Epidemiology Update. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tang X.C. Identification of human neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV and their role in virus adaptive evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111(19):E2018–E2026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Oberholtzer K. National Academies Press; 2004. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak--Workshop Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee J.-W., McKibbin W.J. Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats, National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Simasek M., Blandino D.A. Treatment of the common cold. Am. Fam. Phys. 2007;75(4):515–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bartsch S.M., Lopman B.A., Ozawa S., Hall A.J., Lee B.Y. Global economic burden of norovirus gastroenteritis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Robilotti E., Deresinski S., Pinsky B.A. Norovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28(1):134–164. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00075-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shepard D.S., Coudeville L., Halasa Y.A., Zambrano B., Dayan G.H. Economic impact of dengue illness in the Americas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;84(2):200–207. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bhatt S. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496(7446):504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Durmus Tekir S. PHISTO: pathogen-host interaction search tool. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(10):1357–1358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Karyala P. DenHunt - a comprehensive database of the intricate network of dengue-human interactions. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10(9):e0004965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]