Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 poses an occupational health risk to health-care workers. Several thousand health-care workers have already been infected, mainly in China. Preventing intra-hospital transmission of the communicable disease is therefore a priority. Based on the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety model, the strategies and measures to protect health-care workers in an acute tertiary hospital are described along the domains of work task, technologies and tools, work environmental factors, and organizational conditions. The principle of zero occupational infection remains an achievable goal that all health-care systems need to strive for in the face of a potential pandemic.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Occupational health, SEIPS

1. Preventing Intra-hospital transmission of coronavirus disease 2019

The start of this new decade was dampened by reports of a cluster of novel viral pneumonia in Wuhan City, China. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization declared this emerging infectious disease, now known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern [1] and on 11 March 2020, declared COVID-19 a pandemic [2]. Merely 3 months from the time it has first reported, COVID-19 has spread rapidly from its epicenter in Wuhan City to 113 countries outside of mainland China. At the time of writing, there are more than 118,000 cases globally and almost 4300 fatalities [3].

Singapore reported its first case of COVID-19, diagnosed in a tourist from Wuhan City, on 23 January 2020. Even before the report of the first confirmed case, the Singapore Government had activated a Multi-Ministry Taskforce on 22 January 2020 to marshal a whole-of-government approach in containing the spread and impact of COVID-19 [4].

One of the containment strategies adopted by Singapore's Ministry of Health is to treat and manage all COVID-19 cases within hospitals, while concurrently undertaking rigorous contact tracing to identify, isolate and monitor all contacts with significant exposure to the index cases. Occupational exposure of health-care workers is therefore a real concern that needs to be addressed comprehensively and decisively.

Singapore has learned important lessons from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003. Forty-one % of 238 probable SARS cases in Singapore occurred in health-care workers [5]. Hospital-centric containment efforts were therefore implemented in a bid to curb intra-hospital transmission of SARS. These measures prevented the further unfettered nosocomial spread of SARS, but not before exacting a heavy toll on health-care workers caring for infected patients [6].

Similar to SARS, current evidence indicates that COVID-19 is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets [7]. Infections in health-care workers have already been reported [8]. More than 3000 medical staff were reportedly infected in China by late February 2020 [9].

Singapore's systematic enhancement in capacity and capabilities for pandemic preparedness—from establishing a purpose-build National Centre for Infectious Diseases to stockpiling personal protective equipment (PPE) at the national level—seeks to limit the mortality and morbidity from the next communicable disease outbreak, such as COVID-19, while safeguarding the occupational health of its frontline health-care workers.

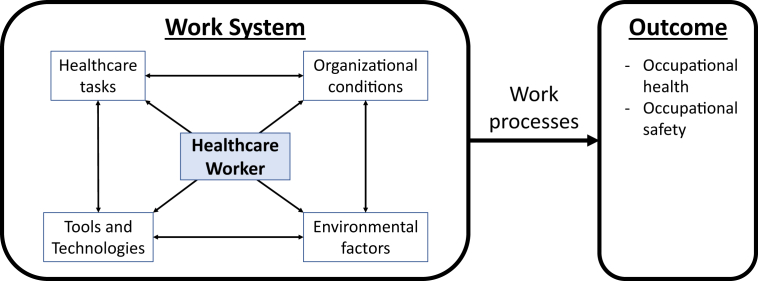

The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) is a human factors–based model used in health care to understand the impact of a work system and processes on outcomes [10]. The model is often used for root cause analyses of incidents involving patient safety, as well as to identify gaps for quality improvement in health care.

Based on the SEIPS model (Fig. 1), the work system describes how a worker performing tasks interfaces with the technologies and tools he or she uses to undertake those tasks, and the physical and organizational conditions he operates within. How well these work system components interact with one another will determine the quality of the outcomes, whether they pertain to job effectiveness or occupational health and safety.

Fig. 1.

Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) Model.

The SEIPS model is a good framework to illustrate the ecosystem of measures taken to prevent the intra-hospital transmission of COVID-19 in an acute tertiary hospital in Singapore.

The health-care worker is at the center of the work system. All other system components, namely work tasks, technologies and tools, environmental factors, and organizational conditions, serve to enable the health-care worker to perform his or her role safely and effectively. Therefore, any measures to strengthen these system components must be worker-centric to facilitate acceptance and implementation.

First, work tasks must be delineated by segregating health-care teams caring for suspect and confirmed cases of COVID-19 from teams managing other patients. This minimizes the risk of cross-infection of patients and health-care workers.

Work tasks also interface with another component of the work system, namely tools. Tasks should be risk-stratified to determine the appropriate tool (PPE) for the health-care worker. The highest risk tasks are aerosol-generating procedures such as airway suctioning, intubation, and bronchoscopy. These warrant the donning of full PPE, including eye protection, disposable gown, gloves, and either an N95 mask or a powered air purifying respirator. Medium risk tasks, such as triaging Emergency Department patients at first presentation for fever and/or respiratory symptoms, require a lower level of PPE. Calibrating the PPE requirements to the occupational exposure risk level, coupled with stepped up audits, improve compliance to the use of PPE where they are most essential.

Second, technologies and tools have a force-multiplying effect on work, while keeping the environment safe for the worker.

Respiratory swab for COVID-19 PCR test is available at the “frontline”, namely the Emergency Department and the hospital's designated clinic to see unwell health-care workers. While not as rapid as point-of-care testing, the turnaround time of 3-4 hours ensures that at-risk patients are identified early and segregated. As part of hospital contamination strategies, these patients are treated in negative pressure isolation rooms, which prevent the spread of the infectious pathogen to the rest of the ward environment.

Twice daily temperature monitoring of all health-care workers is made mandatory to identify those who are unwell and prevent intra-hospital propagation of disease. Utilizing a government-developed IT platform (form.gov.sg), health-care workers are able to log their personal particulars and temperature recordings remotely and securely even when not at work. Health-care workers whose logged temperature readings are higher than 37.5 degree Celsius will be flagged up to the hospital's clinical epidemiology team for further evaluation. This convenience improves compliance, allowing data to be consolidated and analyzed for epidemiological trends.

Third, physical and environmental factors must be reinforced to limit the impact of any hospital transmission of COVID-19 on healthcare delivery.

To minimize the risk of occupational exposure, care teams are segregated in 2 dimensions. Cross-institution coverage by doctors is suspended, and medical staff members are limited to practise in 1 primary institution. Care teams are also kept small to reduce the impact of any inadvertent occupational exposure on personnel downtime owing to the need to quarantine contacts. Meal times for health-care workers are staggered. Didactic teaching and departmental meetings are conducted using video conferencing. Medical students are withdrawn from clinical attachments. These measures, while inconvenient and sometimes painful, are necessary as part of risk mitigation and to sustain a hospital's business continuity should there be cross-infection of and among health-care workers.

Fourth, organizational conditions play a pivotal and influencing role on all other components of the work system.

The most tangible organizational measure is to avail manpower and PPE resources to frontline health-care workers. In a public health crisis, there is global demand for PPE resources but often insufficient supplies, as is the case for COVID-19 [11]. Learning from SARS, one of Singapore's national strategies for pandemic preparedness is the stockpiling of PPE, which has been progressively released to public health-care institutions because the upgrading of the COVID-19 risk assessment level. Within the hospital, demand projection and proactive replenishment of supplies builds resilience within the ecosystem.

The evolving case definitions of COVID-19 makes it challenging for contact tracing, triaging and risk stratification of patients by health-care workers. Policies and infrastructure to support clear and timely communications will facilitate effective cascading of information to frontline staff members, enabling their work and facilitating their interactions with the public [12]. Daily routine instructions disseminated through emails and the use of institution-based social media platforms, such as Workplace from Facebook, are a few of the communications channels being used, allowing access on-the-go and reducing the lag time to important information updates.

The SEIPS model provides a good framework for a health-care system to critically evaluate the armamentarium of measures to minimize the risk of intra-hospital spread, and protect its frontline health-care workers against occupational COVID-19 infection. However, there are limitations that must be highlighted.

The model focusses on the worker as the nexus of interventions. Although extrinsic organizational, infrastructural and procedural conditions are enablers that can be put in place, the intrinsic state and well-being of the health-care worker must also be addressed in order for him or her not to be the weakest link.

In a public health crisis, health-care workers not only have to work harder and longer hours, they often do so in a context where the knowledge and understanding of the novel pathogen is still suboptimal. The regular donning and doffing of full PPE add to physical fatigue and psychological stress.

At this time, it is important for them to be and to feel supported. Clear directions from leadership and a collaborative team spirit will create conducive work conditions and reduce tensions. Peer support programs form part of an organization's crisis management framework. By facilitating more senior medical workers reaching out to provide encouragement, self-care tips and psychological first aid to those in need, these interventions at the personal level strengthen the resilience in our frontline staff.

Another watch area in the use of the SEIPS model is to be mindful of the context of “environment”. Community spread of COVID-19 infections has already been reported [13]. Hence, the environmental ecosystem for prevention of intra-hospital transmission should not be restricted to the hospital alone, nor only inter-health-care worker and health-care worker–patient interactions.

Visitors and outpatients are potential carriers of infectious pathogens into the hospital environment. To minimize this risk, all visitors and outpatients undergo a questionnaire survey of travel and contact history, as well as thermal scanning for fever before they are allowed into the hospital premises. Each inpatient is restricted to only 2 specified visitors through the period of hospitalization. Similarly, each outpatient is only allowed 1 accompanying person when attending the specialist outpatient clinic. These measures serve to reduce the likelihood of introducing COVID-19 from the community into the hospital environment and complements all other preventive measures put in place at the hospital-level.

At this point, it is still too early to gauge the success in achieving the desired outcome of zero occupational infection of COVID-19 in the acute hospital's health-care workers. However, unlike SARS, where 7 of the first 13 SARS cases in Singapore were health-care workers, the country's health-care system is in a more robust, resilient, and safer position today. The principle of zero occupational infection remains an achievable goal that all health-care systems need to strive for, as the world continues its battle against the newest novel infectious disease that has already claimed lives and disrupted normal living at the turn of the decade.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2020.03.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet] 2005. Statement on the second meeting of the international health regulations.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020 [Internet] https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available from:

- 3.World Health Organization . 2020 Mar 11. Coronavirus disease 2019 situation Report 51 [Internet]https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of National Development . 2020 Feb 18. Singapore. Written answer by Ministry of National development on COVID-19 [Internet]https://www.mnd.gov.sg/newsroom/parliament-matters/view/written-answer-by-ministry-of-national-development-on-covid-19 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health . 2003. Singapore. Special feature: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome [Internet]https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/special_feature_sars.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan C.C. SARS in Singapore – key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(5):345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peeri N.C., Shrestha N., Rahman M.S., Zaki R., Tan Z., Bibi S., Baghbanzadeh M., Aghamohammadi N., Zhang W., Haque U. The SARS, MERS and novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Feb 22 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channel News Asia . 2020 Feb 24. China says more than 3000 medical staff infected by COVID-19 [Internet]https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/covid19-china-says-medical-staff-infected-by-coronavirus-12466054 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carayon P., Hundt A.S., Karsh B.-T., Gurses A.P., Alvarado C.J., Smith M., Brennan P.F. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(Suppl. 1):i50–i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Channel News Asia . 2020 Feb 08. Global shortage of masks, protective equipment against coronavirus: WHO chief [Internet]https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/world/wuhan-coronavirus-world-masks-shortage-who-12406572 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong J.E.L., Leo Y.S., Tan C.C. COVID-19 in Singapore – current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020 Feb 20 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J.J., Dong X., Cao Y.Y., Yuan Y.D., Yang Y.B., Yan Y.Q., Akdis C.A., Gao Y.D. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020 Feb 19 doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.