Abstract

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has already taken on pandemic proportions, affecting over 100 countries in a matter of weeks. A global response to prepare health systems worldwide is imperative. Although containment measures in China have reduced new cases by more than 90%, this reduction is not the case elsewhere, and Italy has been particularly affected. There is now grave concern regarding the Italian national health system's capacity to effectively respond to the needs of patients who are infected and require intensive care for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. The percentage of patients in intensive care reported daily in Italy between March 1 and March 11, 2020, has consistently been between 9% and 11% of patients who are actively infected. The number of patients infected since Feb 21 in Italy closely follows an exponential trend. If this trend continues for 1 more week, there will be 30 000 infected patients. Intensive care units will then be at maximum capacity; up to 4000 hospital beds will be needed by mid-April, 2020. Our analysis might help political leaders and health authorities to allocate enough resources, including personnel, beds, and intensive care facilities, to manage the situation in the next few days and weeks. If the Italian outbreak follows a similar trend as in Hubei province, China, the number of newly infected patients could start to decrease within 3–4 days, departing from the exponential trend. However, this cannot currently be predicted because of differences between social distancing measures and the capacity to quickly build dedicated facilities in China.

Introduction

According to Nature, the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is becoming unstoppable and has already reached the necessary epidemiological criteria for it to be declared a pandemic, having infected more than 100 000 people in 100 countries.1 Therefore, a coordinated global response is desperately needed to prepare health systems to meet this unprecedented challenge. Countries that have been unfortunate enough to have been exposed to this disease already have, paradoxically, very valuable lessons to pass on. Although the containment measures implemented in China have—at least for the moment—reduced new cases by more than 90%, this reduction is not the case in other countries, including Italy and Iran.2

Italy has had 12 462 confirmed cases according to the Istituto Superiore di Sanità as of March 11, and 827 deaths. Only China has recorded more deaths due to this COVID-19 outbreak. The mean age of those who died in Italy was 81 years and more than two-thirds of these patients had diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer, or were former smokers. It is therefore true that these patients had underlying health conditions, but it is also worth noting that they had acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pneumonia, needed respiratory support, and would not have died otherwise. Of the patients who died, 42·2% were aged 80–89 years, 32·4% were aged 70–79 years, 8·4% were aged 60–69 years, and 2·8% were aged 50–59 years (those aged >90 years made up 14·1%). The male to female ratio is 80% to 20% with an older median age for women (83·4 years for women vs 79·9 years for men).

On March 8, 2020, the Italian Government implemented extraordinary measures to limit viral transmission—including restricting movement in the region of Lombardy—that intended to minimise the likelihood that people who are not infected come into contact with people who are infected. This decision is certainly courageous and important, but it is not enough. At present, our national health system's capacity to effectively respond to the needs of those who are already infected and require admission to an intensive care unit for ARDS, largely due to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, is a matter of grave concern. Specifically, the percentage of patients admitted to intensive care units reported daily in Italy, from March 1, up until March 11, was consistently between 9% and 11% of patients who were actively infected.

In Italy, we have approximately 5200 beds in intensive care units. Of those, as of March 11, 1028 are already devoted to patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and in the near future this number will progressively increase to the point that thousands of beds will soon be occupied by patients with COVID-19. Given that the mortality of patients who are critically ill with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia is high and that the survival time of non-survivors is 1–2 weeks, the number of people infected in Italy will probably impose a major strain on critical care facilities in our hospitals, some of which do not have adequate resources or staff to deal with this emergency. In the Lombardy region, despite extraordinary efforts to restrict the movement of people at the expense of the Italian economy, we are dealing with an even greater fear—that the number of patients who present to the emergency room will become much greater than the system can cope with. The number of intensive care beds necessary to give the maximum number of patients the chance to be treated will reach several thousand, but the exact number is still a matter of discussion among experts. Health-care professionals have been working day and night since Feb 20, and in doing so around 20% (n=350) of them have become infected, and some have died. Lombardy is responding to the lack of beds for patients with COVID-19 by sending patients who need intensive care but are not infected with COVID-19 to hospitals outside of the region to contain the virus.

Modelling predictions

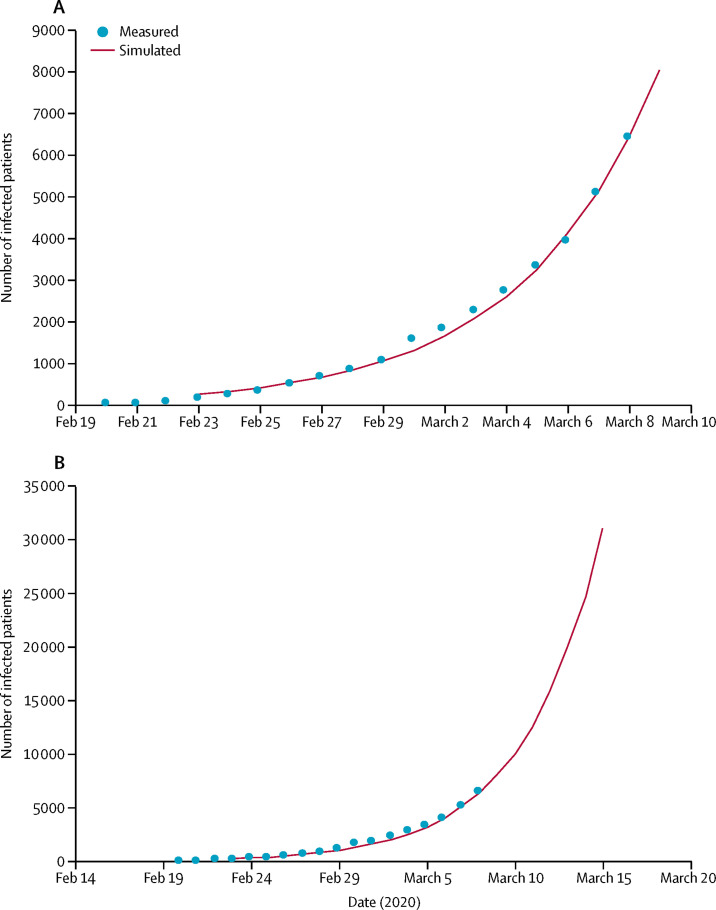

We present the following predictions to prepare our political leaders—those who bear the greatest responsibility for national health systems and the government at the regional level, as well as local health authorities—for what is predicted to happen in the days and weeks to come. They can then implement measures regarding staff resources and hospital beds to meet the challenges of this difficult time. Official numbers of infected people during the COVID-19 virus outbreak in Italy are indicative of the spread of the infection, and of the challenges that will be posed to Italian hospitals and, in particular, intensive care facilities. The number of patients who are infected has been published daily since Feb 21, 2020. It is possible to fit the available data for the number of patients who are actively infected into an exponential model, as reported in figure 1A . The value of the exponent can be computed as r=0·225 (1 per day) and is consistent with the number of infected patients reported by the Italian Health Ministry. The consistency between the exponential prediction and the reported data is very close up until day 17. If the increase in the number of infected patients follows this trend for the next week, there will be more than 30 000 patients infected by March 15, as shown in figure 1B. On the basis of the exponential curve prediction, and the assumption that the duration of infection ranges from 15 to 20 days, it is possible to calculate that the basic reproduction number ranges from 2·76 to 3·25. This number is similar to that reported for the initial phase of the infection outbreak in the city of Wuhan, China3 and slightly higher than 2·2, as reported by Li and colleagues in a more recent report.4

Figure 1.

Measured and predicted number of patients reported to be infected in Italy using an exponential curve

Panel A shows number of infections in previous days and B shows projections for the coming days.

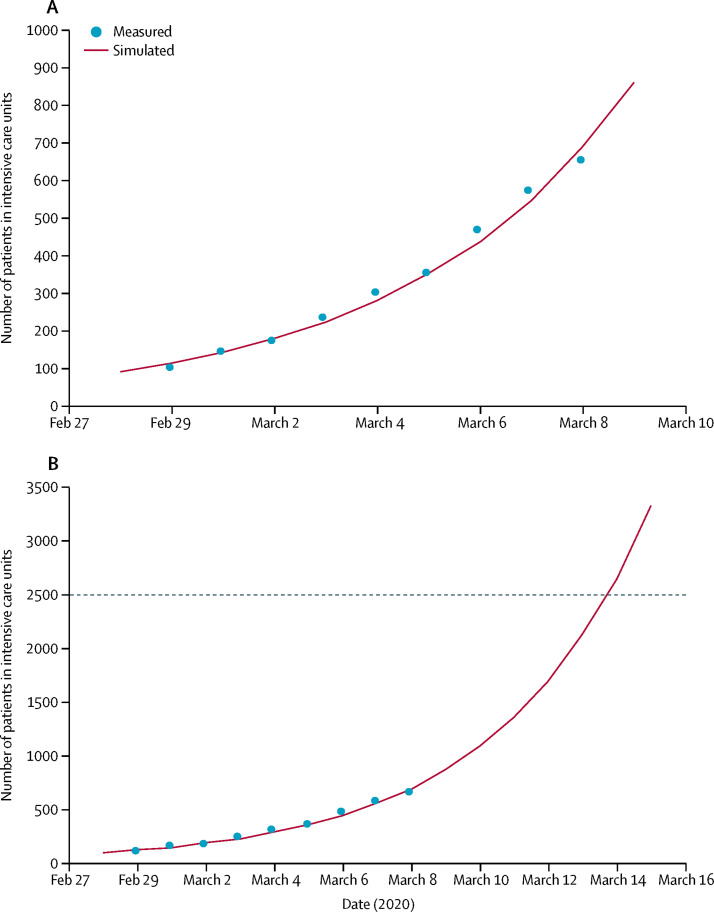

The number of patients admitted to intensive care units increased similarly in Italy, with an exponential trend up until March 8. The best fit of the data reported by the Italian Ministry for Health can be obtained using the same exponent that best fits the number of patients who are infected, as shown in figure 2A . The data available up until March 8 show that the trend in the number of patients who will need admission to intensive care units will increase substantially and relentlessly in the next few days. We can predict with quite a good degree of accuracy that this number will push the national health system to full capacity in a matter of days. Considering that the number of available beds in intensive care units in Italy is close to 5200, and assuming that half of these beds can be used for patients with COVID-19, the system will be at maximum capacity, according to this prediction, by March 14, 2020. This situation is difficult, given that the number of patients who will need to be admitted to the intensive care unit is predicted to further increase after that date, as shown in figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Measured and predicted number of patients in intensive care units in Italy using an exponential curve

Panel A shows number of patients in intensive care units in previous days and B shows projections for the coming days. The dotted line represents the estimated capacity of intensive care beds in Italy.

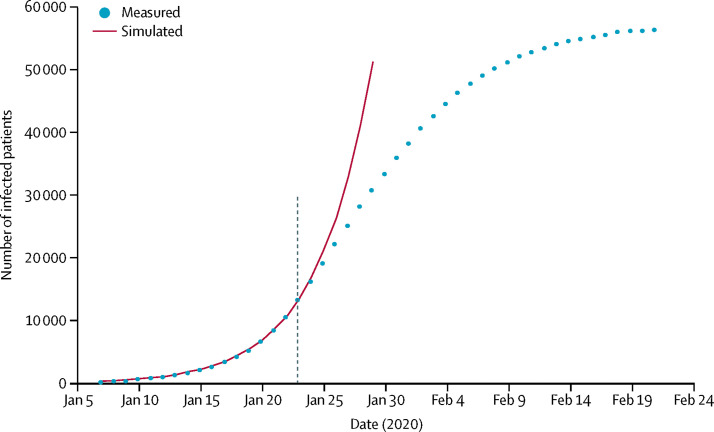

At this point, the most important question is whether the increase in the number of patients who are infected and those requiring intensive care admittance will continue to rise exponentially and for how long. If the change in the slope of the curve does not take place soon, the clinical and social problems will take on unmanageable dimensions, which are expected to have catastrophic results. The only way we can make such predictions is by comparing the trends in the data collected in the Hubei region in China for COVID-19 infection with that for the Italian population. From the official report of the WHO–China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019,5 it is possible to derive the cumulative curve of the patients who are infected from the start of the data series. These data, as reported in figure 3 , show that the initial phase of the infection outbreak followed the expected exponential trend, with the same exponent previously calculated for the number of Italian patients who were infected. Starting Jan 7, the cumulative number of patients who were infected started to diverge from the exponential trend 20 days later. If the Italian outbreak follows a similar trend to that in China, we can suggest that the number of newly infected patients might start to decrease within 3–4 days from March 11. Similarly, we can foresee that the cumulative curve of patients who are infected will peak 30 days later, with the maximum load for clinical facilities for the treatment of these patients foreseen for that period.

Figure 3.

Fitting of cumulative curve of measured infected patients in Hubei, China, with an exponential curve

The dotted line represents the timepoint of the infection outbreak in Italy. It is expected that the number of cumulative patients who are infected will start to deviate from the exponential low in 3–4 days. The plateau of the cumulative curve will be reached just over 30 days from March 11, 2020.

Discussion

The most difficult prediction is the maximum number of infected patients that will be reached in Italy and, most importantly, the maximum number of patients who will require intensive care unit admission. This prediction is of crucial importance to plan for new facilities in Italian hospitals and to calculate the time period in which they need to be available. On the basis that the region of Hubei in China has a slightly smaller population than Italy (approximately 50 million in Hubei and 60 million in Italy), we tentatively assumed that the trend for the maximum number of patients who are actively infected would be similar in the two territories. In doing so, we cannot overlook the fact that the effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak and the extraordinary community measures taken within and outside of Wuhan are unlikely to be replicated elsewhere. Moreover, the current approach to these patients in Lombardy implies non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions, including antiretroviral medication, which might be different from the Wuhan outbreak, and could distort the calculation. We also realise that there is heterogeneity in the transmission dynamics between the city of Wuhan and elsewhere in the province, where the number of people who are infected remains lower. Therefore, it might not be unrealistic to assume that what is going to happen in Italy soon might mirror what happened in Hubei. Of course, it would have been more appropriate to directly compare Greater Wuhan (19 million people) with the region of Lombardy (9 million people), the most seriously affected region in Italy at the moment, but such data are not available.6 We do not currently have additional evidence we can take into consideration to make more robust assumptions regarding the exact number of patients who will be infected in the future days or weeks. On the basis of the available data,5 the number of infected patients reached approximately 38 000 at the end of February, 2020, in the Hubei region, when the number of new cases decreased to almost zero. Given that so far the percentage of patients requiring ARDS treatment is close to 10% for patients who are actively infected, at least in Lombardy, we can assume that we will need approximately 4000 beds in intensive care units during the worst period of infection, which is expected to occur in about 4 weeks from March 11. This is challenging for Italy, as there are now just over 5200 intensive care beds in total. The aim now is to increase this number to safely meet urgent future needs. According to our prediction, we have only a few weeks to achieve this goal in terms of procuring personnel, technical equipment, and materials. These considerations might also apply to other European countries that could have similar numbers of patients infected and similar needs regarding intensive care admissions.

Since 1978, Italy has had the privilege of having a national health system (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale), which was reshaped from 1992–93. Its principles and organisation derive from the British National Health Service model, and it is based on three fundamental principles. The first principle is universality—all citizens have an equal right to access services provided by the national health system. The second is solidarity—every citizen contributes to financing the national health service based on their means, through progressive taxation. The third is uniformity—the quality of the services provided by the national health service to all citizens in all regions must be uniform. All individuals are supposed to pay for it as taxpayers, each person giving a little to receive a lot in return, if they become unwell.

Conclusion

In theory, we are in a better position than many other countries to react to the current outbreak. However, an aggressive approach needs to be taken with patients who are critically ill with SARS-CoV-2, often including ventilatory support. The system's capacity to respond to changing circumstances has been under enormous pressure, at least in the Lombardy region, where two clusters have already emerged since Feb 21. We predict that if the exponential trend continues for the next few days, more than 2500 hospital beds for patients in intensive care units will be needed in only 1 week to treat ARDS caused by SARS-CoV-2-pneumonia in Italy. In the meantime, the government is preparing to pass legislation that will enable the health service to hire 20 000 more doctors and nurses and to provide 5000 more ventilators to Italian hospitals. These measures are a step in the right direction, but our model tells us that they need to be implemented urgently, in a matter of days. Otherwise, a substantial number of unnecessary deaths will become inevitable. Intensive care specialists are already considering denying life-saving care to the sickest and giving priority to those patients most likely to survive when deciding who to provide ventilation to. This attitude has already been criticised by the current President of the Italian Comitato di Bioetica who, in a recent declaration to lay press stated that the Constitution recognises the right of every individual to receive all necessary health care. They might not recognise that the reality is that intensive care wards are overflowing with patients and that COVID-19 is not a benign disease. Our doctors and nurses are modern heroes in an unexpected war against a difficult enemy. In the near future, they will have no choice. They will have to follow the same rules that health-care workers are left with in conflict and disaster zones. We hope that the present analysis will help political leaders and health authorities to move as quickly as they can to ensure that there are enough resources, including personnel, hospital beds, and intensive care facilities, for what is going to happen in the next few days and weeks. Finally, our analysis tends to suggest that measures to reduce transmission should certainly be implemented, as our government did on March 9, by inhibiting people's movement and social activities, unless strictly required. Rather than revising the Schengen visa-free zone, the most effective way to contain this viral outbreak in European countries is probably to avoid close contact at the individual level and social meetings in each country.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Kerstin Mierke for writing assistance.

Contributors

AR was responsible for data analysis and statistics, and writing of the manuscript. GR was responsible for data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Declarations of interest

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Callaway E. Time to use the p-word? Coronavirus enter dangerous new phase. Nature. 2020;579:12. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Economist Tourism flows and death rates suggest covid-19 is being under-reported. 2020. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/03/07/tourism-flows-and-death-rates-suggest-covid-19-is-being-under-reported

- 3.Leung G, Wuhttps J. Real-time nowcast and forecast on the extent of the Wuhan CoV outbreak, domestic and international spread. 2020. https://www.med.hku.hk/f/news/3549/7418/Wuhan-coronavirus-outbreak_AN-UPDATE_20200127.pdf

- 4.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. published online Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Mission Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- 6.Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases. 2020. https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/