Abstract

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia emerged in Wuhan, China. Since then, this highly contagious COVID-19 has been spreading worldwide, with a rapid rise in the number of deaths. Novel COVID-19–infected pneumonia (NCIP) is characterized by fever, fatigue, dry cough, and dyspnea. A variety of chest imaging features have been reported, similar to those found in other types of coronavirus syndromes. The purpose of the present review is to briefly discuss the known epidemiology and the imaging findings of coronavirus syndromes, with a focus on the reported imaging findings of NCIP. Moreover, the authors review precautions and safety measures for radiology department personnel to manage patients with known or suspected NCIP. Implementation of a robust plan in the radiology department is required to prevent further transmission of the virus to patients and department staff members.

Key Words: Coronavirus, COVID-19, pneumonia, infection control, safety

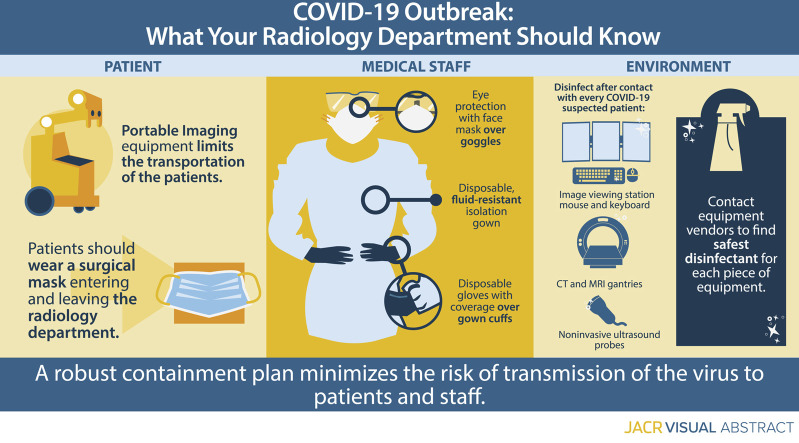

Visual abstract

Background

Coronaviruses are nonsegmented, enveloped, positive-sense, single-strand ribonucleic acid viruses, belonging to the Coronaviridae family [1]. Six types of coronavirus have been identified that cause human disease: four cause mild respiratory symptoms, whereas the other two, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, have caused epidemics with high mortality rates.

In December 2019, a new type of coronavirus called COVID-19 was extracted from lower respiratory tract samples of several patients in Wuhan, China. These patients presented with symptoms of severe pneumonia, including fever, fatigue, dry cough, and respiratory distress. Novel COVID-19–infected pneumonia (NCIP) is believed to have originated in a seafood market in Wuhan. The virus, which has been reported in 28 countries as of this writing, has shown human-to-human transmission [2,3] and has been classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The mean incubation period is estimated to be 5.2 days, which allows air travelers to spread the disease globally [4].

Evidence shows that virus transmission can occur during the incubation period in asymptomatic patients. Moreover, high sputum viral loads were found in a patient with NCIP during the recovery phase [5]. As of February 5, 2020, more than 25,000 confirmed cases have been reported worldwide, with a rapid rise in the number of deaths. The World Health Organization has called the outbreak a global health emergency.

Imaging is critical in assessing severity and disease progression in COVID-19 infection. Radiologists should be aware of the imaging manifestations of the novel COVID-19 infection. A variety of imaging features have been described in similar coronavirus-associated syndromes. In this brief review, we discuss the epidemiologic and radiologic features of coronavirus syndromes, with a focus on the known imaging features of NCIP. In addition, precautions and safety measures for radiology department personnel in managing patients with known or suspected NCIP are discussed.

SARS: Epidemiology and Imaging

SARS coronavirus was first recognized in 2003 after a global outbreak originating in southern China. The virus spread to 29 countries globally, affecting 8,422 patients, with a mortality rate of 11%. The transmission of this coronavirus occurs via large droplets and direct inoculation [6]. The virus may remain viable for up to 24 hours on dry surfaces, but it loses its infectivity with widely available disinfectants such as bleach and formaldehyde [7].

Initial chest radiography in individuals with SARS will frequently show focal or multifocal, unilateral, ill-defined air-space opacities in the middle and lower peripheral lung zones [8], with progressive multifocal consolidation over a course of 6 to 12 days involving one or both lungs [9]. Chest CT will show areas of ground-glass opacity and consolidation in involved segments.

MERS: Epidemiology and Imaging

MERS coronavirus infection was first reported in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 2012 [10]. Since then, approximately 2,500 laboratory-confirmed human infections have been reported in 27 countries, with a mortality rate reaching more than 30% [11]. The risk for transmission to family members and health workers seems to be low. Despite the potential for epidemics through Hajj pilgrimages in Saudi Arabia, there has not been a notable outbreak recently. It seems that in contrast to the human-to-human pathway as the main route of virus spread in SARS coronavirus, the transmission in MERS coronavirus occurs mainly through nonhuman, zoonotic sources (eg, bats, camels) [12,13].

In 83% of patients with MERS coronavirus infection, initial radiography will show some degree of abnormality, with ground-glass opacities being the most common finding [14]. Likewise, CT will show bilateral and predominantly ground-glass opacities, with a predilection to basilar and peripheral lung zones, but observation of isolated consolidation (20%) or pleural effusion (33%) is not uncommon in MERS [15].

NCIP: What Do We Know?

Patients with COVID-19 infection present with pneumonia (ie, fever, cough, and dyspnea). Although fatigue is common, rhinorrhea, sore throat, and diarrhea uncommonly occur. A recent report in The Lancet described the clinical manifestations of NCIP in 41 patients [16]. According to that report, abnormal chest imaging findings were observed in all patients, with 40 having bilateral disease at initial imaging. This early report on the presentation of the NCIP in intensive care unit patients indicated bilateral subsegmental areas of air-space consolidation, whereas in non–intensive care unit patients, transient areas of subsegmental consolidation are seen early, with bilateral ground-glass opacities being predominant later in the course of the disease (Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3 ). Serial chest radiography of a 61-year-old man who died of NCIP showed progressively worsening bilateral consolidation during a course of 7 days. Another report on 99 individuals with confirmed NCIP described similar imaging findings, with bilateral lung involvement in 75% and unilateral involvement in 25% [17]. Another study of five individuals in a family cluster with NCIP [18] described bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities, with more extensive involvement of lungs parenchyma in older family members. The reported imaging features most closely resemble those of MERS and SARS. No pleural effusion or cavitation has been reported so far in confirmed cases of NCIP, but pneumothorax was reported in 1% of patients (1 of 99) in a study by Chen et al [17]. Overall, the imaging findings are highly nonspecific and might overlap with the symptoms of H1N1 influenza, cytomegalovirus pneumonia, or atypical pneumonia. The acute clinical presentation and history of contact with a COVID-19-infected patient or history of recent travel to an eastern Asian country (eg, China, South Korea, or Japan), Italy, or Iran should raise clinical suspicion for the diagnosis of NCIP. Although further investigations on the clinical and radiologic aspects of the COVID-19 are ongoing, imaging will continue to be a crucial component in patient management.

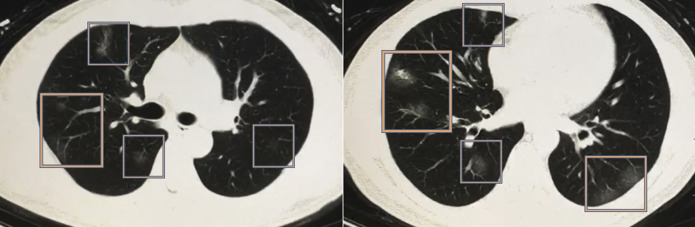

Fig 1.

Chest CT scan from a 50-year-old male Chinese patient with a confirmed diagnosis of novel COVID-19-infected pneumonia. The patient presented with low-grade fever, cough, sneezing, fatigue, and lymphopenia. Multiple peripheral ground-glass opacities are present in both lungs (predominant on the right side), with a subpleural distribution. Imaging findings are nonspecific and might be seen with other viral pneumonias as well. Images are courtesy of Min Liu, MD, Department of Radiology, China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Beijing, China).

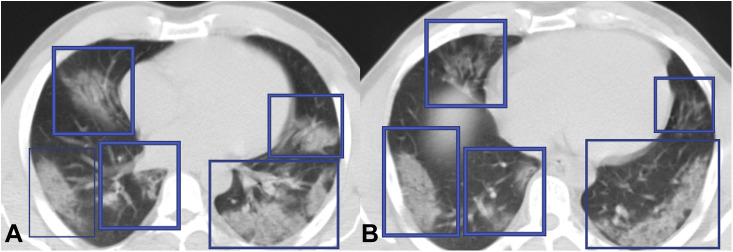

Fig 2.

Chest CT scan of a 50-year-old Iranian man with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. The patient presented with low-grade fever, cough, respiratory distress, and confusion. Extensive subpleural and peripheral multifocal areas of consolidation (A, B) are seen in both lungs, predominantly in lower lobes.

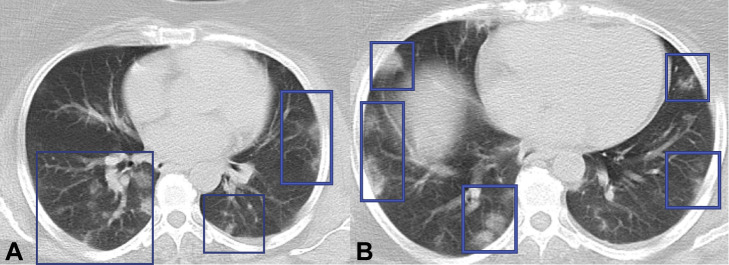

Fig 3.

Chest CT scan of a 48-year-old woman with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. The patient presented with fever and cough. Small ill-defined subpleural and peripheral areas of consolidation (A, B) are noted in both lungs which are nonspecific in this patient with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Precautions for Radiology Department Personnel

Radiographers are among the first-line health care workers who might be exposed to 2019 novel COVID-19. Diagnostic imaging facilities should have guidelines in place to manage individuals with known or suspected COVID-19 infection. The novel COVID-19 is highly contagious and is believed to transmit mostly through respiratory droplets, but there is uncertainty as to whether the virus can be transmitted by touching a surface or an item that is contaminated (ie, a fomite). A thorough understanding of the routes of virus transmission will be essential for patients’ and health care professionals’ safety. Droplets have the greatest risk of transmission within 3 ft (91.44 cm), but they may travel up to 6 ft (183 cm) from their source [19]. For the purpose of diagnostic imaging in individuals with NCIP, whenever possible, portable radiographic equipment should be used to limit transportation of patients. On the basis of experience with SARS, the use of a satellite radiography center and dedicated radiographic equipment can decrease the risk for transmission from known infected individuals. If a patient needs to be transported to the radiology department, he or she should wear a surgical mask during transport to and from the department.

As of March 4, 2020, for providers, the World Health Organization recommends respiratory protection with use of a standard medical mask, unless aerosol-generating procedures are performed. [20,21]. Additional guidelines from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend airborne precautions and the use of a N95 mask or higher when in close contact with patients who have COVID-19 or are under investigation for the virus. In addition, the droplet precaution instruction recommends appropriate personal protective equipment, including a disposable isolation gown with fluid-resistant characteristics, a pair of disposable gloves with coverage over gown cuffs, eye protection with goggles, and if possible a face mask over goggles [22]. In a study of 254 medical staff members who had been exposed to SARS coronavirus, the risk for virus transmission was significantly reduced by using droplet and contact precautions [23].

CT and MR machine gantries, noninvasive ultrasound probes, blood pressure cuffs, and image viewing station mice and keyboards need to be disinfected after every contact with suspected patients. According to the Spaulding classification of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA, these surfaces need to be either washed with soap and water or decontaminated using a low-level or intermediate-level disinfectant, such as iodophor germicidal detergent solution, ethyl alcohol, or isopropyl alcohol. Environmental services staff members need to be specifically trained for professional cleaning of potentially contaminated surfaces after each high-risk patient contact [24]. Radiology departments should contact their equipment vendors to find the safest disinfectant for each piece of equipment in use.

US health care imaging facilities need to be prepared for the escalating incidence of new cases of COVID-19. If appropriately prepared, radiology department staff members can take greater measures to manage the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the facility and personnel. A multidisciplinary committee should convene to outline guidelines to prevent the spread of the virus through human-to-human contact and the department equipment. Implementation of a robust plan can provide protection against further transmission of the virus to patients and staff members.

Take-Home Points

-

▪

The imaging features of COVID-19 pneumonia are highly nonspecific and are more often bilateral with subpleural and peripheral distribution and range from ground-glass opacities in milder forms to consolidations in more severe forms.

-

▪

If properly prepared, radiology department personnel can take measures to manage the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the department and staff.

-

▪

Continued data collection and larger epidemiologic studies are needed for both a full range of imaging findings and routes of transmission.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Dr. Min Liu, MD, Department of Radiology; China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China, for his valuable contribution to this article.

Footnotes

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest related to the material discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Weiss S.R., Leibowitz J.L. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv Virus Res. 2011;81:85–164. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385885-6.00009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. In press. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan-Yeung M., Xu R.H. SARS: epidemiology. Respirology. 2003;8(suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampathkumar P., Temesgen Z., Smith T.F., Thompson R.L. SARS: epidemiology, clinical presentation, management, and infection control measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:882–890. doi: 10.4065/78.7.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul N.S., Roberts H., Butany J. Radiologic pattern of disease in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: the Toronto experience. Radiographics. 2004;24:553–563. doi: 10.1148/rg.242035193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong K.T., Antonio G.E., Hui D.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic appearances and pattern of progression in 138 patients. Radiology. 2003;228:401–406. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282030593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available at:

- 12.Mobaraki K., Ahmadzadeh J. Current epidemiological status of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the world from 1.1.2017 to 17.1.2018: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:351. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3987-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacIntyre C.R. The discrepant epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Environ Syst Decis. 2014;34 doi: 10.1007/s10669-014-9506-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das K.M., Lee E.Y., Al Jawder S.E. Acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: temporal lung changes observed on the chest radiographs of 55 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W267–W274. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das K.M., Lee E.Y., Langer R.D., Larsson S.G. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: what does a radiologist need to know? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:1193–1201. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.-H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel J.D., Rhinehart E., Jackson M., Chiarello L., Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10 suppl 2):S65–S164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020, February 27; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or persons under investigation for COVID-19 in healthcare settings. 2020, February 21; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Finfection-control.html. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Supplement I: infection control in health care, home, and community settings: public health guidance for community-level preparedness and response to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) https://www.cdc.gov/sars/guidance/i-infection/index.html Available at:

- 23.Seto W.H., Tsang D., Yung R.W. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361:1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirza S.K., Tragon T.R., Fukui M.B., Hartman M.S., Hartman A.L. Microbiology for radiologists: how to minimize infection transmission in the radiology department. Radiographics. 2015;35:1231–1244. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015140034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]