Abstract

Over the past 200 years lung diseases have shifted from infections – tuberculosis, pneumonia – to diseases of dirty air – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and lung cancer. New diseases have emerged from industrial pollution and HIV infection, while better imaging has revealed others previously unrecognized. Scientific advances in microbiology, imaging and clinical measurement have improved diagnosis and allowed better targeted treatment. Advances in treatment have been dramatic, the most important being drugs (antibiotics, cortisone, β2-adrenoceptor agonists), ventilatory support (from iron lung to nasal positive-pressure ventilation), inhaled therapy (metered dose inhalers, nebulizers) and lung surgery (resections, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, transplantation). Delivery of care has shifted from sanatoria for the rich but nothing at all for the poor, to universal coverage in both primary and hospital care. Generalists have turned into super-specialists and doctors have been joined by growing numbers of professions allied to medicine. Management of lung disease has vastly improved but the impact of disease remains.

Keywords: Delivery of care, epidemiology, history, medical and surgical advances, MRCP

Key points.

Over the past 200 years:

-

•

Infections have declined but some have returned, while asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer have surged

-

•

Scientific advances, especially in imaging and microbiology, have improved diagnosis

-

•

New targeted treatments with antibiotics, corticosteroids, ventilatory support and lung surgery have revolutionized management

-

•

Delivery of care has shifted from inefficient remedies for the rich to specialized treatment for all

Introduction

The lungs are the most exposed of the internal organs and have throughout the past 200 years occupied centre stage for disability and death. The diseases have changed: some fade, some emerge and others come and go, but all through this period our knowledge has grown. We understand these breathing bags better than ever before, we can see into them in ways unimagined in the 19th century, and we have a growing armamentarium to fight their disorders. Some key events are listed as a historical timeline of respiratory medicine (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Timeline of developments in lung medicine (1850–2010)

| Decade | General | Techniques | Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840s | Edwin Chadwick report on poor living conditions Communist manifesto Cigarette manufacture begins |

Hutchinson spirometer Hygiene, hand-washing |

Artificial pneumothorax |

| 1850s |

Pickwick Papers – sleep apnoea La Traviata – tuberculosis Irish potato famine |

Florence Nightingale nursing Compulsory vaccination |

Chloroform anaesthesia Sanatoria Thoracocentesis |

| 1860s | Karl Marx Das Kapital London sewers built |

Lister antisepsis | Nelson's inhaler Nebulizers |

| 1870s | Public Health Act UK | Pasteur germ theory of disease | |

| 1880s | Koch identifies Mycobacterium tuberculosis Friedlander identifies pneumococcus |

First thoracoplasty | |

| 1890s | Mass production cigarettes | Roentgen, first chest X-ray | |

| 1900s | Free school meals Old age pensions |

Positive-pressure ventilation via endotracheal tube Rigid bronchoscopy |

|

| 1910s | World War I Spanish flu |

Cigarette rations to soldiers | |

| 1920s | Lung cancer linked to smoking | Drinker's iron lung BCG vaccine |

|

| 1930s | St Louis and Meuse valley smogs | Pneumonectomy Flu vaccination First sulfonamide |

|

| 1940s | National Health Service (UK) Asbestos gas masks Essay: ‘How the poor die’ (Orwell) |

Streptomycin Penicillin |

|

| 1950s | Cancer–smoking link (Doll) Clean air act |

Metered dose inhaler invented | Isoniazid Cortisone |

| 1960s | Environmental movements | First lung transplant | |

| 1970s | Drug abuse as public enemy no 1 Anti-smoking movement |

Computed tomography Magnetic resonance imaging Fibreoptic bronchoscopy |

Inhaled corticosteroids Pneumococcal vaccine Rifampicin Long-term oxygen therapy |

| 1980s | HIV epidemic Film Whose Life is it Anyway? |

Nasal non-invasive ventilation Continuous positive airway pressure ventilation for sleep apnoea Successful lung transplants |

|

| 1990s | Film Philadelphia (HIV) | Cystic fibrosis gene identified | Long-acting β-adrenoceptor agonists |

| 2000s | Severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic Smoking ban First e-cigarettes |

Portable oxygen concentrators | Biopharmaceuticals |

Changing patterns of disease

Change is sometimes real and sometimes where the spotlight falls. Lung diseases surge and sometimes seem to go. Pneumonia finished off Sir Francis Bacon in 1626 as he stuffed a chicken full of snow, killed Rene Descartes in 1650 as he taught freezing philosophy lessons to Queen Christina of Sweden and Leo Tolstoy in 1910 in a lonely railway station. Tuberculosis (TB) gave John Keats a far from easeful death in 1821 but provided Violetta in 1853 with the best last act of all in La Traviata. And then these two captains of the men of death drifted away. Antibiotics cured them and left the theatre empty for the diseases of dirty air.

Foul smoke inhalation lifted lung cancer from zero to hero, promoted chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from the wings to centre stage, and gave small cameo parts to interstitial lung diseases. The air became opaque with coal dust underground, while up above asbestos and other factory chemicals were inhaled, lingered in the lungs and slowly scarred them. New chapters were written into books of lung pathology, new X-ray patterns described. Asthma annoyed William of Orange and Charles Dickens but was never a 19th-century celebrity. However, 100 years later, with the help of Bill Clinton and David Beckham, it became a star; allergy replaced psychology as the cause, and big pharma smelt and dealt in gold. Sleep apnoea moved on from Dickens' fat boy snoring in the background to crest the wave of obesity and became the fastest growing branch of lung disease.

And then, just as the audience was beginning to forget them, came the triumphal re-entry of the infections. TB, declining long before the discovery of streptomycin – but only in the countries of the rich – returned. Of course, it had never really left at all, surging on among the malnourished and overcrowded in poorer countries. Drug-resistant bacteria emerged and TB deaths rose again. Pneumonia, too, had never gone away. Osler in the 1920s named it the ‘old man's friend’ and may have been right for Donald Bradman in 2001 or Ronald Reagan in 2005. But pneumonia was no friend to the increasing numbers of immunocompromised individuals, their defences weakened by malnutrition (George Orwell in ‘How the poor die’), cancer treatments or, from 1981, HIV (Freddie Mercury in 1991). Other viruses hit the headlines. Spanish flu killed 50 million people in 1918, and since then smaller flu epidemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome have shown that, in spite of vaccination, viruses are still very effective killers.

Investigation of the lungs

In 1850, eyes, hands, nose and ears – minimally aided by a stethoscope – were all the doctor had. He could see pallor, cyanosis or a flapping tremor but did not understand them. He could feel chest movements and tap out different tones with elegant percussive fingers but had no idea of what was going on inside. He could smell anaerobes (new-mown hay with an arrière gout of stale faeces), and he could wield a stethoscope as an instrument of erudition rather than understanding. His drug treatments were herbs – poppy, willow bark, stramonium, wormwood – and his surgical skills were few. TB was treated with rest, varying diets and lifestyle changes. Love and sex in particular had to be avoided – difficult as in sanatoria there was little else to do. Acute infections and fevers were cupped, bled or scarified, partly in order to remove bad humours and partly to structure time while waiting for nature to kill or cure. Did the doctor do more harm than good? No one knew.

Then came the age of scientific discovery. Three key advances were Pasteur's germ theory of disease, Roentgen's discovery of X-rays and Chadwick's linking of infection to poor living conditions. Pasteur used microscopy (microbes could be seen and classified) to explain diseases, Semmelweis insisted on hygiene – puerperal fever could be prevented by clean hands – John Snow mapped the epidemiology of cholera to a water tap, and Lister sprayed antiseptic. At least as important as any technical advance, although less glamorous, was Edwin Chadwick's report The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842), leading to new public health laws. Study of lung physiology led to tests of function – Hutchinson's 1842 spirometer was the pathfinder.

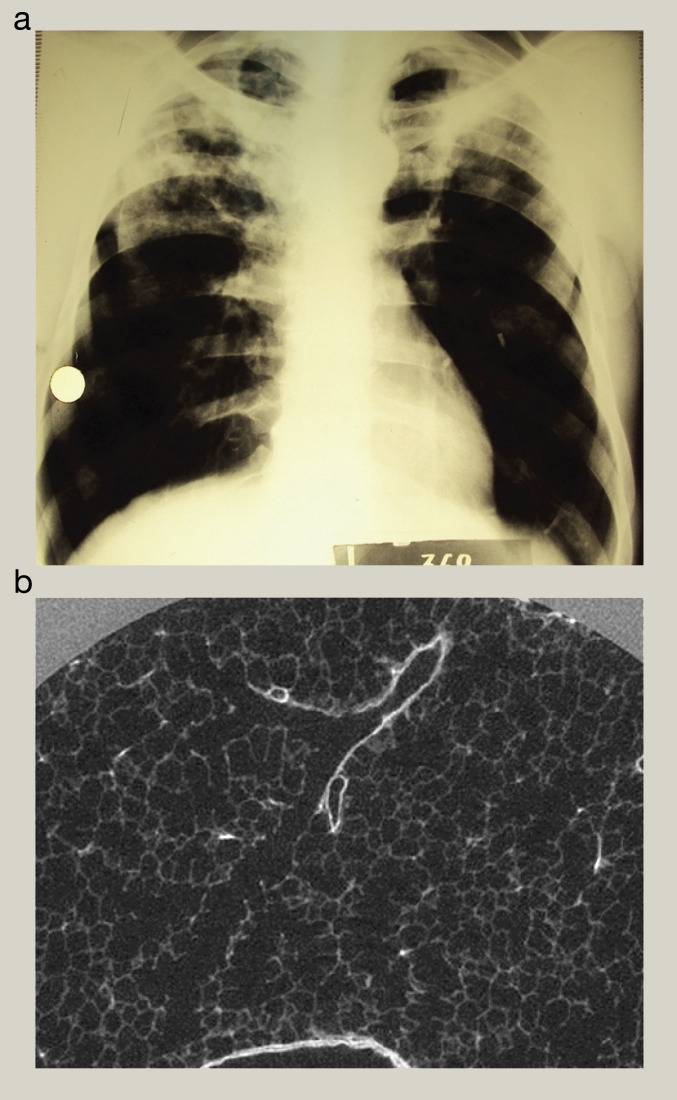

The 20th century saw a cascade of scientific discoveries, but much more important was development and application of the earlier discoveries. Microbiologists gave us precise diagnosis and the tools to develop vaccines and antibiotics. Radiologists showed what was really going on, culminating in computed tomography scanning (1970), with its ever-greater resolution rivalling histopathology (Figure 1 ). Public health improved with housing laws, school meals, free milk, mass mini X-ray vans and programmes of vaccination.

Figure 1.

(a) Resolution of a chest X-ray (centimetres). (b) Resolution of a computed tomography scan (micrometres). Courtesy of Professor David Hansell.

Lung function testing developed more slowly, taking 100 years to move from Hutchison's lung volumes to Tiffeneau's flow rates. This was followed by a major academic push in the 1950s to understand gas exchange, with attempts to make carbon monoxide transfer and body plethysmography clinically useful. More important, however, were blood gas measurements. Today spirometry is encouraged in primary care, with occasional benefits over peak flow meters, but simple oximeters have become an essential tool of lung medicine.

Endoscopy took off slowly from the first laryngoscopy in 1849 to rigid bronchoscopy (1904), toughed out with either no anaesthesia at all or, for wimps, cocaine spray. All changed in the 1970s with Japanese fibreoptics; by 1980 diagnostic bronchoscopy was being carried out by physicians, not surgeons.

Treatment

Science and luck precede new treatments by 10–50 years. The three main types – drugs, devices and surgery – hit the healthcare market in completely different ways. New drugs get the most attention as they are launched with a fanfare, they can be prescribed as soon as they are approved, and all doctors can use them. Patients report instant improvement and the makers make money. Device development is slower but at least as important. Specialists start to use them and slowly the word goes round. Slower still and much more invisible to patients and primary care are advances in surgery.

Drugs

Three out of thousands of new chemical drugs revolutionized lung treatment. Antibiotics came first and deserve first prize. Synthetic sulfonamides in the 1930s were toxic and unsuitable for systemic use. Moulds had been used to treat infections for centuries before Fleming investigated penicillin in 1928 (Poland, France, Italy, Belgium and Costa Rica can all claim to have got there first); Florey and Pfizer were essential in taking it on to manufacture in 1942. Then came streptomycin (1944), tetracycline (1945), chloramphenicol (1947), erythromycin (1949), isoniazid (1952) and rifampicin (1957). The transition from watching an infection to treating it was dramatic, and it must have been a wonderful era to be a doctor.

Close behind came the miracle of cortisone. In 1949, patients with rheumatoid arthritis picked up their beds and walked, and the wonder drug began to cure all known diseases; recreational use led to cortisone parties in New York. By 1955, the benefits and adverse effects had been quickly established clinical observation – controlled trials take longer. Asthma attacks responded to treatment, and with inhaled corticosteroids came long-term control. Third prize goes to the β-adrenoceptor agonists, first isoprenaline, then salbutamol and finally the long-acting β-adrenoceptor agonists. Selective β2-adrenoceptor agonists are among the world's best-selling drugs for asthma, COPD, sporting performance and beef production.

Devices

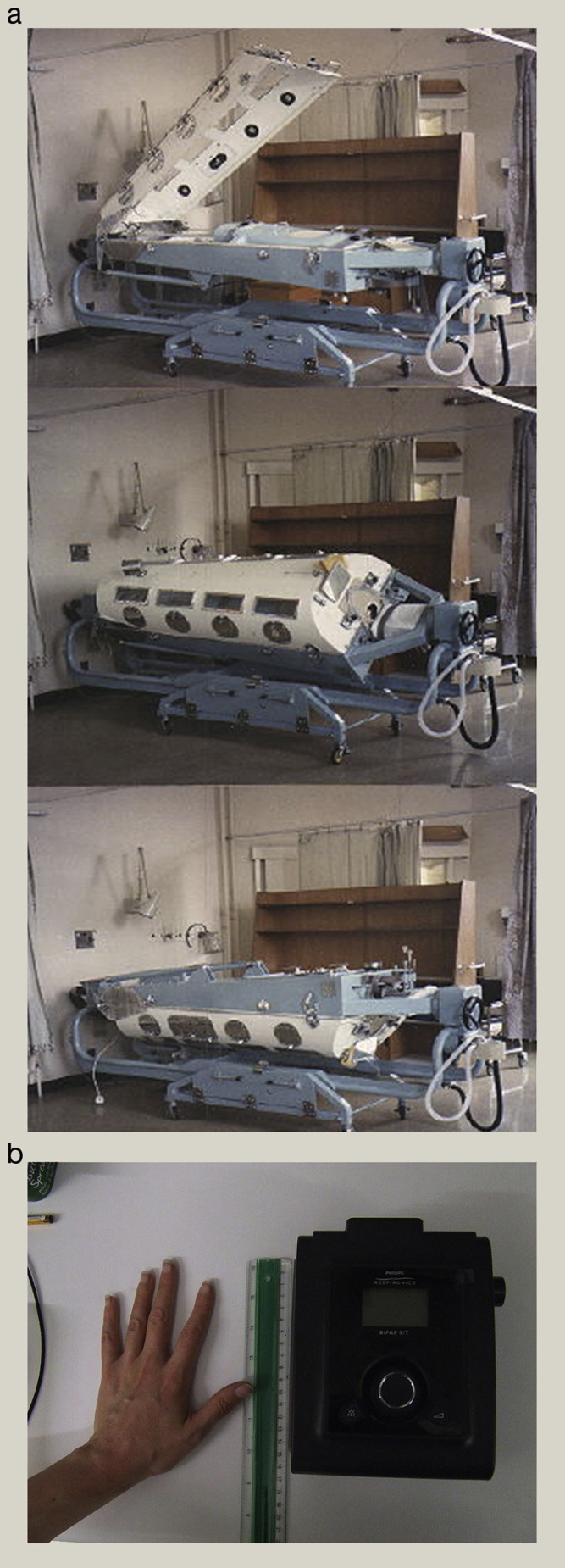

Again, there are hundreds of these. Some assist ventilation, some get drugs in or mucus out, but two types dominate the field: ventilators and inhalers. The simplest positive-pressure support devices, bag and mask, work but endotracheal tube and intensive care are better. Drinker's iron lungs (1927) countered respiratory paralysis from polio, other negative-pressure devices – turtles, ponchos and cuirasses – being less effective. In the 1980s, non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation took off, and devices have been improving ever since (Figure 2 ), keeping hundreds of thousands of people alive who would, 100 years ago, have died. Linked to this are oxygen delivery devices; cylinders, liquid oxygen reservoirs and cumbersome concentrators have been replaced by neat portable versions weighing <2 kg.

Figure 2.

(a) Iron lung for negative-pressure ventilation. (b) Small ventilator for home positive-pressure ventilation. Courtesy of Professor Michael Polkey.

Old inhalers were inefficient: steam with pleasant-smelling herbs is soothing and still enjoyed today but delivers little to the lungs. Nebulizers started in the 1870s with a squeeze-bulb version, but the particle size needed for penetration into the lungs was not understood until the 1950s. The first efficient metered dose inhaler, based on perfume spray technology, was launched in 1955 and has lasted well. Dry powder inhaler research started in 1930s; the Aerohaler® (1949) did not work, the Rotahaler® (1960s) and Spinhaler® (1970s) worked to some degree, but the 1990s Turbohaler and Diskhaler were good and there are now >30 different versions. Big pharma did all the research as it was rather too hum-drum for academia.

Surgery

It takes many small steps to climb a mountain. Key steps were endotracheal intubation (1904), anaesthetic gases (chloroform 1847, halothane 1951), antisepsis (1870s), blood groups and safe transfusion (1901), antibiotics (1940s) and, most important of all, brave pioneers. Each new operation builds on the experience of others; artificial pneumothorax (1830s) moved on to thoracoplasty (1880s) and plombage (1920s). The first survival from pneumonectomy was in 1931; the next 16 patients died. Eventually, surgery for TB turned into lung cancer resection in the 1950s. Drainage of pleural fluid was routine from 1850 (Axel Munthe describes draining an empyema in a pet ape during a home visit in The Story of San Michele in 1929). Thoracoscopy started in 1910 and advanced in the 1970s with fibreoptics. It has since developed into video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for investigation of pleural disease, lung biopsy, treatment of pneumothorax and simple resections. Lung transplantation opened new and wonderful prospects for end-stage lung disease with the first successful operations in the 1970s, and has now become routine, albeit limited by scarcity of donor organs.

Thoracic surgery led on to heart surgery, and by the 1960s there was a danger that lung surgery would be left behind. However, in the 1970s, lung surgery developed separately and has flourished. Organizational change can be as important as technical.

Delivery of care

Lung medicine was a major part of the general doctor's workload in the 19th century until the 1850s sanatorium movement – well described by Thomas Mann in The Magic Mountain and AE Ellis in The Rack – and this specialization led to chest clinics. These were alongside but separate from hospitals and endured professional snobbery. General physicians looked down on chest physicians (‘Chest – yes, physician – never’) before the systems were integrated in the 1960s. Today, the lung specialist is often the best general physician. TB nurses morphed, after a brief spell in the wilderness, into respiratory nurses with their own training programmes. Some work in primary care and some are specialist nurses in hospitals and have been joined by respiratory therapists, specialist physiotherapists, lung function measurers, psychologists and the rest. The room can now be very full as a single patient faces hoards of multidisciplinary professionals sharing out the management.

In spite of all this change, lung disease, a major killer 150 years ago, remains a major killer today.

Further reading

- 1.Chadwick E. 1842. The sanitary condition of the labouring population.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Chadwick [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis A.E. Vallencourt; Richmond, VA: 1958. The rack. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann T. new edn. Everyman’s Library; London: 2005. The magic mountain. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munthe A. new edn. John Murray; London: 2004. The story of San Michele. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orwell G. Shooting an elephant; and other essays. Penguin Modern Classics; London: Penguin: 2003. How the poor die. [Google Scholar]