Abstract

As an atypical pneumonia began to appear in December 2019, Zhou et al. worked with remarkable speed to identify the associated virus, determine its relationship to animal viruses, and evaluate factors conferring infection susceptibility and resistance. These foundational results are being advanced to control the current worldwide human coronavirus epidemic.

Within a short time after recognizing a novel infectious respiratory syndrome in Wuhan, China, dedicated virologists at the center of the outbreak completed groundbreaking work to identify the agent of disease. Their investigations, reported in Zhou et al. [1], began with next-generation sequencing of nucleic acids in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of diseased patients. From the sequence data, a novel coronavirus was identified and provisionally named 2019-nCoV. The 2019-nCoV RNA virus genome is closely related to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV that emerged in human populations in 2003–2004 to cause epidemic disease and to several SARS-related CoVs in bats that are known to have the potential for human infection [2]. Thus, 2019-nCoV is now renamed ‘SARS-CoV-2’. It is alarming that SARS-CoV-2 has expanded far beyond that of the previous 2003 SARS-CoV, spreading to over 40 countries and infecting over 80 000 individuals as of 25 February 2020. The infection is associated with a SARS-like disease [3], with a case fatality rate at 3.4%. The SARS-CoV-2/coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic has been designated a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization.

Zhou and coworkers [1] set the stage to address this public health emergency. They developed quantitative PCR-based methods to detect SARS-CoV-2 infections. Using these methods, they verified the respiratory tract as a principal infection site and established preliminary time courses of virus amplification and clearance in patients. Subsequent detailed clinical investigations demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 is detected within 1–2 days after patient symptoms, peaking 4–6 days later and clearing within 18 days [4]. Seroconversion was evident at that time, with abundant virus-specific IgG measured approximately 20 days after disease onset. These are the findings that help to define transmissibility periods and inform public health authorities on appropriate quarantine measures.

In addition, the Shi group isolated SARS-CoV-2 from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of a diseased patient [1]. The virus propagated on monkey and human cells and, notably, parallel investigations by others demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 also productively infected primary human airway epithelial cells [3]. Using in vitro infection assays, Zhou et al. discovered that convalescent sera from surviving patients convincingly neutralized infections [1]. Moreover, in an initial assessment of broad antibody-mediated protection, they found that horse anti-SARS-CoV serum cross-neutralized SARS-CoV-2 infections [1]. Therefore, one can be optimistic about the prospects for broad antibody-mediated immunity against current and future zoonotic SARS-related CoVs, although much work lies ahead to identify vaccines that can elicit appropriate neutralizing antibodies.

Using the isolated SARS-CoV-2 virus, the authors subsequently identified a critical host susceptibility factor [1]. When cultured cells overexpressed the transmembrane protein angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) protein from humans, bats, pigs, or civet cats, they became hypersensitized to infection, showing that ACE2 is a SARS-CoV-2 receptor [1]. These findings harken back to the earlier SARS-CoV, which also utilizes both human and animal ACE2 proteins as receptors and exhibits a zoonotic distribution that matches its binding to the ACE2 receptor orthologs [5]. They also reflect the behavior of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, which, although relying on a distinct dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) protein receptor, similarly disseminates among animal species in correlation with its binding to DPP4 orthologs.

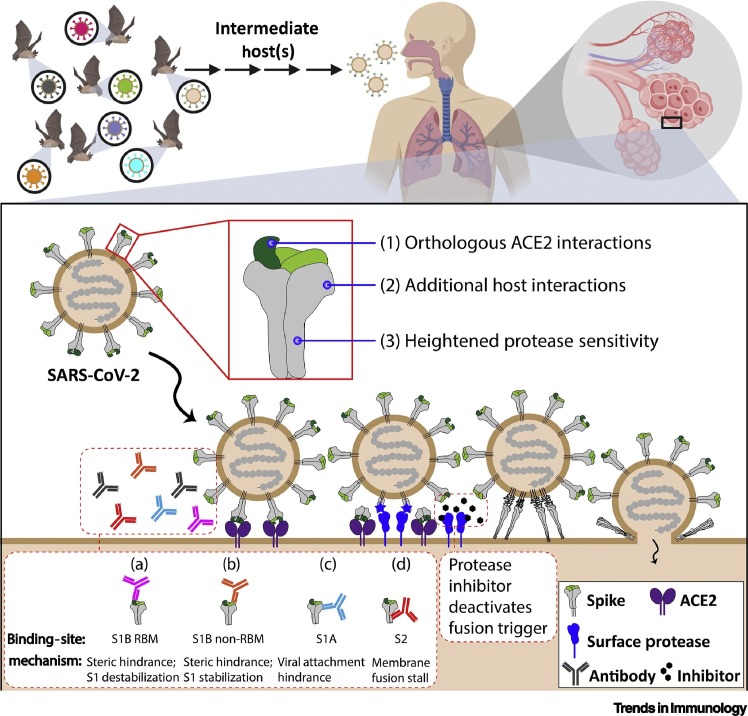

The findings by Zhou and colleagues highlight interactions of the entering SARS-CoV-2 virus with host factors; specifically those interactions with the ‘corona’ of spike (S) proteins projecting from virus membranes. The most threatening bat-derived CoVs are those with distinctively human-tropic S proteins (Figure 1 , top). Once inside human lungs (Figure 1, bottom), S proteins interact with host susceptibility factors, including receptors and proteases, which causes massive protein conformational changes triggering virus–cell membrane fusion and infection. S-specific neutralizing antibodies and antiviral agents interfere with these susceptibility factors and protect from infection.

Figure 1.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-CoV-2 Zoonosis and Cell Entry.

Bat SARS-related CoVs (top left) are thought to transmit through intermediate host(s), with a select subset of viruses having features necessary to infect the human respiratory tract (top right). Infection (lower panel) requires SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) engagement with host angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors. Subsequently, surface proteases cleave S2, the fusion-mediating subunit of S, which triggers a series of conformational changes that result in fusion between the viral envelope and the target cell membrane. Features of SARS-CoV-2 that may facilitate human infection include: (1) S1B receptor-binding motifs (RBMs) (in green) that bind orthologous ACE2 receptors; (2) a S1A domain that may confer additional host interactions; and (3) a furin protease cleavage substrate that may confer heightened sensitivity to host protease cleavages [9]. Antiviral antibodies (lower-left inset) prevent infection by: (a) binding S1B RBMs, blocking receptor access; (b) binding distal to RBMs, sterically interfering; (c) binding S1A, possibly preventing alternative attachment to distinct receptors; and (d) binding S2, arresting membrane fusion. Attractive antiviral compounds include protease inhibitors [10], which deactivate membrane fusion triggering and suppress virus entry. This figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

This report by Shi’s group [1] and broader knowledge of CoV entry frame important questions. Which animal CoVs have the greatest potential for human infection? For SARS-related CoVs, addressing this question amounts to identifying those animal CoVs that bind human ACE2 receptors. Structural bioinformatics approaches are helpful here, because even before the Zhou et al. report [1], insights made in silico accurately predicted that SARS-CoV-2 spikes bind human ACE2 [6]. Surveillance methods using cell culture models will further address this question, when testing human cell infection with SARS-related animal CoVs and paying close attention to those viruses isolated from wildlife in close proximity with humans. Which CoVs transmit human disease? Recent structural and biochemical analyses of SARS-CoV-2 S proteins [7] begin to address this question. The receptor-binding domains on the SARS-CoV-2 S proteins bind with high affinity to human ACE2 [7], which may explain the facile transmissibility of this virus. However, additional host interactions may also correlate with transmission and disease, and Zhou et al. noted unique features on a separate (N-terminal) domain of the SARS-CoV-2 S proteins that may confer binding to alternative host-cell receptors [1]. Alternative host cell interactions by these N-terminal domains warrant consideration, as it is known that analogous domains on several human CoVs have important auxiliary cell-binding functions [8]. SARS-CoV-2 S proteins have also acquired several basic residues (RRAR/S), forming a furin protease cleavage site. Temporal progression of proteolytic scissions prime and then activate SARS-CoV S proteins to catalyze virus–cell membrane fusion [9]. Thus, the SARS-CoV-2 furin substrate site is likely to facilitate the priming cleavage step, which sensitizes S proteins to the subsequent activating cleavages occurring on susceptible target cells, and facilitates virus entry and infection, as depicted in Figure 1. Consequently, the hypothesis that heightened protease sensitivities account, in part, for SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility and disease certainly merits further exploration.

Quarantine measures are in place to limit the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, but the risk of a global pandemic is real. The development of effective vaccines and antiviral drugs is a priority to reduce the burden of this virus. An immediate challenge is to construct SARS-CoV-2 S-based vaccines that display conserved epitopes and elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies as well as virus-specific T cell responses. Similar daunting tasks lie ahead in identifying safe and effective drugs that suppress SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication and in making recommendations for their clinical use. If given too late, they may not modify the disease course, even if virus loads are diminished. Committed research communities can and will build from the foundational knowledge that is now in place and respond appropriately to these challenges.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIAID AI 060699).

References

- 1.Zhou P. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menachery V.D. SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:3048–3053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517719113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou L. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. Published online February 19, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005;24:1634–1643. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Y. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. Published online January 29, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wrapp D. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. Published online February 19, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park Y. Structures of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein in complex with sialoside attachment receptors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0334-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belouzard S. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y. Protease inhibitors targeting coronavirus and filovirus entry. Antivir. Res. 2015;116:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]