Abstract

Like other low-income countries, limited data are available on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in Pakistan. We conducted a systematic review of studies on PPE use for respiratory infections in healthcare settings in Pakistan. MEDLINE, Embase and Goggle Scholar were searched for clinical, epidemiological and laboratory-based studies in English, and 13 studies were included; all were observational/cross-sectional studies. The studies examined PPE use in hospital (n = 7), dental (n = 4) or laboratory (n = 2) settings. Policies and practices on PPE use were inconsistent. Face masks and gloves were the most commonly used PPE to protect from respiratory and other infections. PPE was not available in many facilities and its use was limited to high-risk situations. Compliance with PPE use was low among healthcare workers, and reuse of PPE was reported. Clear policies on the use of PPE and available PPE are needed to avoid inappropriate practices that could result in the spread of infection. Large, multimethod studies are recommended on PPE use to inform national infection-control guidelines.

Keywords: Respiratory tract infections, Influenza, Infection control, Personal protective equipment, Health personnel, Pakistan

Introduction

Healthcare workers are at the frontline when treating infectious disease cases and at high risk of acquiring influenza and other respiratory infections [1], [2], [3]. Several outbreaks of new infectious diseases have occurred in recent decades, such as the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002–2003 [4], influenza pandemic (H1N1) in 2009 [5], Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012 [6] and Ebola virus diseases in 2014–2016 [7]. Many healthcare workers were infected and died during these outbreaks because of a lack of infection control [4], [8], [9], [10] Various infection control strategies are used to protect healthcare workers from respiratory and other infections in healthcare settings [11], [12]. These strategies can be broadly classified as administrative control measures, environmental control measures and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Administrative control measures include developing policies and procedures, implementing triage protocols and providing health education and trainings. Environmental control measures includes ensuring proper ventilation, establishing airborne infection isolation and negative pressure rooms, developing systems for cleaning and waste disposal. [13], [14]. PPE is commonly used in healthcare settings as standard or transmission based precaution to protect healthcare workers from infections and to prevent further spread to patients around them [14], [15].

PPE is generally ranked lowest in the infection control hierarchy due to less effectiveness compared to other control measures and high expenditure in the long run. Therefore, most infection control guidelines recommend using PPE together with other administrative and environmental control measures. However, PPE is important during the early stage of an outbreak or a pandemic when drugs, a vaccine and other control measures are not available, or access is limited. Commonly used PPE to protect from respiratory infectionsare; face masks, respirators, gloves, and goggles or face shields [16]. Face masks (or medical masks) and respirators are the most commonly used PPE to protect from influenza and other respiratory infection in healthcare settings. However, these two products are not the same. Face masks are not designed for respiratory protection and are used to avoid respiratory droplet and spray of body fluids on the face. They are also used by sick patients to prevent spread of pathogens to others (referred to as “source control”), or by surgeons in the operating theatre to maintain a sterile operating field. Face masks are not fit to the face and have varying filtration capacities [17]. Respirators are designed for respiratory protection and are used to protect from respiratory aerosols [18]. A properly fitted respirator provides better protection again respiratory infections than a face mask. Gloves are used to protect hands from blood and body fluids, including respiratory secretions. Goggles and face shields are used to prevent transfer of respiratory pathogens into the eyes from contaminated hands and other sources. Gowns, coveralls, surgical hoods and shoe covers can also be used where procedures on infectious patients generate aerosols or when a new respiratory virus has emerged [18].

There is an ongoing debate about the selection and use of various types of PPE in healthcare settings. This is mainly because of a lack of high quality studies on the use of PPE. Most studies are observational and on the use of masks and/or respirators [18]. To date, only five randomized clinical trials have been conducted on use of PPE in hospital settings and all were on face masks/respirators [18]. Moreover, most studies on PPE use were conducted in high/middle income countries and currently there are limited data from low-income countries where the burden of infectious diseases is high. It is therefore important to examine the use of PPE in low resource countries to inform infection control policies.

Pakistan has a population of about 200 million. As a low-income country, its gross domestic product is low, as is its expenditure on health [19]. The country has one of highest rates of infant and maternal mortality in the south Asia region. Infectious diseases are still among the main causes of death, particularly in young children. Health and surveillance systems are generally weak and limited data are available on infection prevention and control strategies. The aim of this study was to examine the use of PPE for respiratory infections in healthcare settings in Pakistan.

Methods

Study design

A systematic review was conducted using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search strategy

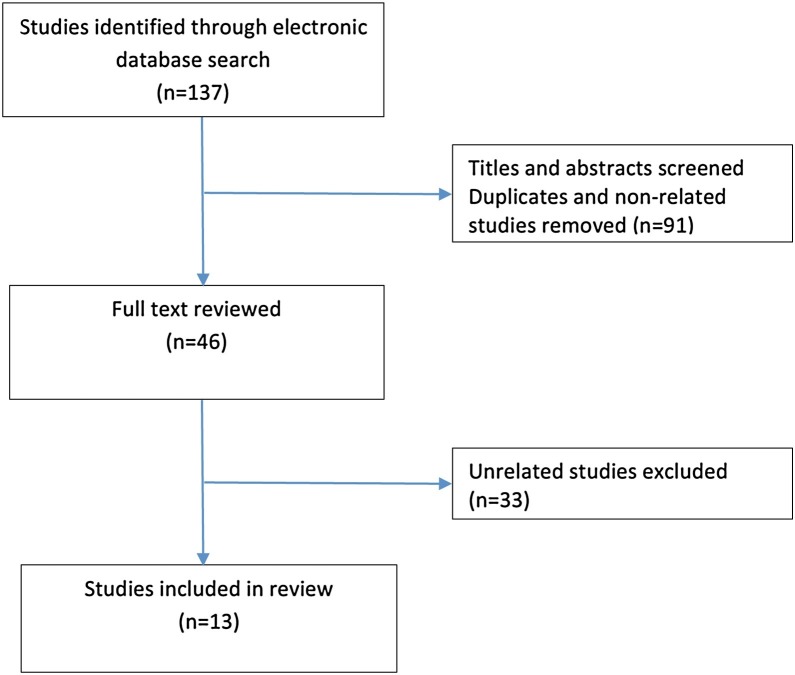

We searched for studies on the electronic databases MEDLINE and Embase using selected key words. A combination of keywords were used including: ‘face mask’ OR ‘mask’ OR ‘medical mask’ OR ‘surgical mask’ OR ‘cloth mask’ OR ‘respirator’ OR ‘gloves’ OR ‘gowns’ OR ‘coverall’ OR ‘surgical cap/hood’ OR ‘shoe/boot covers’ OR ‘goggles’ OR ‘face shield’ OR ‘eye protection’ AND ‘ respiratory infection’ OR ‘respiratory tract infection’ OR ‘respiratory diseases’, ‘outbreaks’ OR ‘infectious disease’ OR ‘influenza’ OR ‘pandemic influenza’ OR ‘flu’ OR ‘tuberculosis’ OR ‘pneumonia’ AND ‘Pakistan’ OR ‘Punjab’ OR ‘Sindh’ OR ‘Balochistan’ OR ‘Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’. We used an open date strategy up to December 2017. We anticipated that studies published in local journals might not be indexed on the MEDLINE or Embase, therefore, an additional search was made on Google Scholar using the same keywords. We set a limit of 20 results per page on Google Scholar and first three pages were reviewed for each keyword search. After the initial search; we reviewed titles and abstracts and selected studies for full text review (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

Selection of studies

Clinical, epidemiological and laboratory-based studies conducted in any part of Pakistan and published in English were included in the review. The focus of this systematic review was on the use of PPE for prevention of respiratory infections. Therefore, we only included those studies which examined the use of facemask and/or respirator in healthcare settings, with or without other PPE. We only included those studies where PPE was discussed for respiratory infections. Studies where PPE was examined for general infection control were also included, given respiratory protective equipment (face masks and/or respirators) was mentioned. We excluded studies on the use of PPE only for bloodborne infections. Conference abstracts and poster presentations were also excluded.

Results

Types of studies

A total of 137 studies were found in the initial search. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 46 studies were selected for full text review. Finally, 13 articles were included in this review (Table 1 ) [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. We only found observational/cross-sectional studies on the use of PPE for infectious diseases in healthcare settings in Pakistan. In all studies data were collected through questionnaires or interviews. No clinical trials or laboratory-based studies on the use of PPE in such settings were found. Seven studies examined the use of PPE in hospital [20], [21], [22], [23], [25] and among those, two examined the PPE perceptions among medical students [24] or pharmacy students [32]. Two studies were conducted in the laboratory settings [26], [27] while, four in dental settings [28], [29], [30], [31] Two studies focused on the use of PPE for influenza [24], [32], two were for tuberculosis [20], [25] and nine studies were on multiple respiratory diseases, including influenza [21], [22] or general infections [23], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. Only two studies examined the use of PPE alone [21], [22], while other studies examined other infection control practices as well [20], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32].

Table 1.

Studies on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare settings in Pakistan.

| Author/study year | Study design | Participants | PPE included in the study* | Disease focus | Main findings* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waheed et al. 2017 [20] |

Descriptive study (observation and interviews) | 100 HCWs and 100 patients in 10 hospitals managing drug-resistant tuberculosis all over Pakistan | Face masks, respirators | Drug-resistant TB | Low compliance with face masks and respirators because of unavailability and discomfort |

| Chughtai et al. 2014 [21] | Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 5 healthcare managers in health departments | Face masks, respirators | Influenza, SARS and TB | Various types of masks and respirators are recommended for these diseases |

| Chughtai et al. 2015 [22] | Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | Infection control coordinators in 55 secondary and tertiary hospitals in Punjab | Face masks, respirators | Influenza, SARS and TB | Various types of masks and respirators are used for these diseases. Medical masks are used in most hospitals. |

| Baqi et al. 2009 [23] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 13 inpatient units of a 1750-bed tertiary-care hospital in Karachi | Laboratory coats, gloves, face masks, eye shields | General infections | Masks and gowns were not available in some units and gowns were shared among wearers |

| Hussain et al. 2012 [24] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 251 medical students in Hyderabad | Face masks | Influenza (H1N1 pandemic) | 75% (181/241) of the participants preferred to use a face masks for influenza H1N1 |

| Javed et al. 2012 [25] |

Cross-sectional study using a questionnaire | 150 HCWs, including doctors, nurses and non-medical staff in medical units of a tertiary-care hospital in Karachi | PPE (details not provided) | TB | PPE was used by 25% (38/150) HCWs for suspected TB cases and 56% (84/150) for confirmed TB cases |

| Nasim et al. 2012 [26] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire and interviews | 1782 laboratory technicians from public and private sector laboratories across the country | Laboratory coats, gloves, face masks, eye shield | General infections | 31.9% of laboratory workers did not use any PPE. Gloves and laboratory coats the were most commonly used PPE |

| Nasim et al. 2010 [27] | Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire and interviews | 253 laboratory technicians working in the public and private sector in Karachi | All PPE | General infections | 46.2% of laboratory technicians did not use any PPE |

| Khan et al. 2012 [28] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 200 dentists from two large dental hospitals in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Gloves, face masks, eye shields | General infections | 94% used gloves, 68% use face masks and 35% use eye shields |

| Ahmed 2014 [29] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 251 dentists from dental colleges, hospitals and private clinics in Karachi | Gloves, face masks, caps, Laboratory coats, surgical gowns, protective eye wear | General infections | PPE use varied across the facilities and practitioner groups. The use of face masks and gloves was common, while the use of gowns, surgical caps and eye protection was not |

| Bokhari et al. 2009 [30] |

Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 333 dental practitioners in Lahore | Gloves, face masks | General infections | Qualified practitioners used gloves (94.35% vs 28.2%) and face masks (97.5% vs 80.3%) significantly more often than unqualified practitioners |

| Mohiuddin et al. 2015 [31] | Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 120 dentists at the Institute of Oral Health Sciences in Karachi | Gloves, face masks, eye protection | General infections | 98% (118/120) of dentists change gloves after each patient. 74% (89/120) of participants routinely used face masks |

| Rahim et al. 2017 [32] | Cross-sectional survey using a questionnaire | 443 final-year pharmacy students in seven universities in Karachi | Face masks, gloves, other PPE | Pandemic influenza | 57% (254/443) of participants believed that influenza could be prevented by the use of PPE |

TB: tuberculosis, HCW: healthcare workers, SARS: severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Only PPE-related findings are presented in the table.

Guidelines on PPE use

Guidelines and standard operating procedures on PPE do not exist in most of the hospitals [23] or laboratories [26], [27] in Pakistan. Two studies examined the guidelines and current practices on the use of face masks/respirators for influenza, tuberculosis and SARS in Pakistan [21], [22]. Recommendations on the use of masks were reported to be inconsistent and different types of product were recommended and used in various healthcare settings [21], [22].

Type of PPE used

Face masks were the most commonly used PPE to protect from respiratory infections in most hospitals in Pakistan. Medical masks were generally used to protect from influenza, tuberculosis and other respiratory infections, while the use of respirators was limited to high-risk situations [21], [22]. In a cross-sectional survey among final-year pharmacy students in seven universities of Karachi, about 60% of 443 participants highlighted the need to cover the nose or mouth to protect from influenza and about 57% highlighted the use of face masks, gloves and other PPE [32]. Laboratory coat and gloves were the most commonly used PPE in the laboratories in Pakistan while face masks and eye covers were rarely used [26], [27]. A survey of dentists working in various settings (dental colleges, hospitals and private clinics) showed that face masks and gloves were also commonly used PPE [29].

Practices around PPE use

The use of PPE was also reported to be low among health workers. According to a hospital-based survey, face masks are not provided to patients with tuberculosis and respirators are not provided to the healthcare workers [23]. Another survey showed that 25% of participants used PPE for patients with suspected tuberculosis and 56% used PPE for patients with confirmed tuberculosis [25]. A study in a ward for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis reported that 65% of the healthcare workers used N95 respirators and 58% were provided with a mask [20]. A study on 253 biosafety level (BSL) 2 laboratory workers showed that PPE was not used by about half of the staff (46.2%) [27]. A countrywide survey showed that almost one third (31.9%) of BSL-2 laboratory workers did not routinely use PPE [26]. Both gloves and laboratory coats were used by only 26.7% of the personnel, while a laboratory coat or gloves alone were used by 30.4% and 8.1%, respectively. Less than 1% of all the respondents across Pakistan reported using eye covers [26]. In a survey of medical students during pandemic (H1N1) 2009, 75% said that they would use a face mask to protect from infection. Students with less risk perception were more hesitant to use face masks [24]. The use of face masks was common in dental practice and according to various surveys, 68–100% of dentists wear masks during dental procedures [28], [29], [30], [31]. Across all the studies in dental settings, more than 90% also used gloves. Among the PPE, face masks were considered the most bothersome to use by wearers.

Availability of PPE

Reuse of PPE was also reported in many studies, mainly because of unavailability of PPE and lack of training. Gowns are shared among the healthcare workers in hospital many times [23]. Two surveys in dental clinics showed that more than half of the dentist reuse masks during routine work [28], [29]. The availability of PPE was generally low in all healthcare settings [21], [22], [28] and varied according to the type [23]; gloves and masks were available while gowns and N95 respirators were not available in several wards [23]. A shortage of PPE was also reported during SARS and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 [21], [22]. A lack of training was a common issue reported and most healthcare workers were not trained in the use of PPE.

Other infection control

Most of the studies (11/13) discussed other infection control practices as well, in addition to the use of PPE. Other non-standard infection control practices included reuse of syringes, improper waste disposal, a lack of hand hygiene practices, non-isolation of infectious cases and low influenza vaccination among healthcare workers.

Discussion

We reviewed the use of PPE in various healthcare settings in Pakistan. A lack of guidelines and standard operating procedures, inconsistent policies and practices, low compliance, and non-availability and reuse of PPE were the main issues highlighted in this study. Evidence is lacking on the use of PPE in hospitals and other healthcare settings in Pakistan and most studies are of low quality. Clinical studies should be conducted to examine the effectiveness of PPE and improve the compliance. Reuse of PPE may increase the risk of self-contamination to the wearer and this practice should be discontinued. There is a need to improve the availability of PPE and healthcare workers should be trained. PPE is generally considered lowest in the infection control hierarchy and is generally recommended in combination with other control measures. Other infection control practices in such settings should also be examined.

Different types of PPE are used by healthcare workers in Pakistan, which reflects a lack of standard policies and guidelines. The different policies and practices may be because of the different recommendations by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [33], [34]. Debate continues about the selection and use PPE for different infections, for example, face masks versus respirators, gowns versus coveralls, face shields versus goggles [7], [18], [34], [35]. Selection of PPE mainly depends on mode of transmission, however, several individual and organizational factors also contribute the selection and use of PPE, such as risk perception, presence of adverse events, pre-existing medical illness, availability and cost [7]. Respiratory infections are generally transmitted through contact, droplet and/or airborne routes. Gloves should be used to protect from infections transmitted through contact (e.g. respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus), face masks should be used for droplet infections (e.g. influenza and coronavirus) and a respirator should be used to protect form airborne infection (e.g. tuberculosis and measles). However, infection transmission is rarely by only one route and most infections are transmitted by more than one route [36]. For example, influenza and SARS primarily transmit through droplet and contact routes, but airborne transmission has also been reported [37], [38]. Similarly, Ebola primarily transmits through direct contact with blood and body fluids [39], but animal studies have shown that airborne transmission is also possible [7]. The risk of transmission further increases during aerosol-generating and other high-risk procedures [40], [41]. Moreover, uncertainty exists about how pathogens transmit during outbreaks and pandemics [14], [34], [42], [43]. Therefore, superior PPE should be used where the mode of transmission is uncertain, the case-fatality rate is high and pharmaceutical interventions are not available [7]. Infection control guidelines in Pakistan need to be updated urgently to reflect these recommendations. Given that MERS CoV is circulating in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), policies and practices on the use of PPE in other countries of the region should also be examined.

Our study also reported low availability of PPE in hospital, dental and laboratory settings in Pakistan. The availability of PPE is a challenge, not only in low-resource counties, but also in high-income countries, particularly during outbreaks and pandemics when the use of PPE greatly increases [46], [47]. This may result in non-standard practices such as reuse and extended use of PPE. Shortages of PPE were even reported in many high-income countries during the 2009 influenza H1N1 pandemic and staff had to use various alternatives [46], [47], [48]. The availability of PPE is important to ensure proper use and compliance. Low use of PPE among laboratory workers in Pakistan may be due to non-availability and a lack of resources. For example, PPE use was relatively higher in laboratory workers in Punjab, which is an affluent province, than other provinces [26]. Moreover PPE use was reported more in the private sector in Pakistan than the public sector which has fewer resources [27]. Proper use of PPE depends on several factors such as availability, knowledge, training, risk perception and comfort [7], [44], [45].

This study showed the compliance with the use of PPE was generally low among healthcare workers and was mainly due to unavailability of PPE, discomfort and a lack of training. While the use PPE depends on many factors, a greater perception of risk was positively associated with compliance [24]. Continuous use of face masks and respirators may have psychological and physiological effects on the wearer and result in more adverse events [49], [50], [51]. Compliance with the use of face masks has been shown to be based on the nature of the disease, infectiousness of patients and the performance of high-risk procedures [52]. Previous studies have tested the PRECEDE (predisposing, reinforcing and enabling) framework to examine healthcare workers’ compliance with universal precautions [53]. The results showed that reinforcing factors, such as availability of PPE and less job hindrance, and enabling factors, such as safety climate and regular feedback, were significant predictors of compliance with PPE [53]. In addition, the health belief model [54] was also used to examine the compliance and use of face mask during the SARS outbreak [55], [56]. Perceived susceptibility (vulnerability to acquiring SARS and close contact with case), perceived benefits (that face masks can prevent infection) and cues to action (someone asked them to use face masks) were significant predictors of protective behaviour and use of face masks [55].

Our study showed that most healthcare workers were not trained on the use of PPE in Pakistan. The risk of infection can be reduced with proper training and availability of policies and standard operating procedures [57]. However, regular monitoring is also required to make sure that healthcare workers are using PPE according to the protocols. A study in the US reported many deviations from the protocols even though all healthcare workers were trained [15]. This may result in self-contamination to the wearers and the spread of infection to others [58]. Training programmes should be arranged for newly recruited staff and then annual refresher courses should be provided.

Our study had some limitations. The initial search was made on MEDLINE and Embase but very few studies were retrieved because many papers are not indexed on these databases. Therefore, we also searched Google Scholar but we only reviewed the first 3 pages after each search so some studies could have been missed. However, we checked the references lists of the relevant studies and could not find any other studies. Our search was up to 2017 and studies in 2018 were not included. We only considered PPE in this study and did not examine other infection control practices. The use of PPE is generally recommended with other administrative and environmental control measures.

Conclusions

The selection and use of PPE vary according to the type of healthcare worker and working environment. Face masks and gloves were the most commonly used PPE to protect from respiratory and other infections. Overall, compliance with the use of PPE was low, and non-availability and reuse of PPE were reported. Most studies were observational and large-scale prospective studies are needed to collect more evidence about the use of PPE in healthcare settings in Pakistan.

Funding

No funding sources.

Competing interests

AAC tested the filtration of mask samples by 3 Min in another study; 3M products were not used in this study. WK declares none.

Ethical approval

As this was a systematic review of published data, ethics approval was not required.

Authors’ contributions

AAC devised the structure and topic areas for this review and made the initial search. WK and AAC reviewed titles and abstracts and selected studies for full text review. AAC prepared the first draft of manuscript and both authors contributed equally to the final manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has been previous published in Volume 12, Issue 4 and it has been reprinted for this special issue.

References

- 1.Bellei N., Carraro E., Perosa A.H., Benfica D., Granato C.F. Influenza and rhinovirus infections among health-care workers. Respirology. 2007;12:100–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komitova R., Kunchev A., Mihneva Z., Marinova L. Nosocomial transmission of measles among healthcare workers, Bulgaria. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(15) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baussano I., Nunn P., Williams B., Pivetta E., Bugiani M., Scano F. Tuberculosis among health care workers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:488–494. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.100947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Emergencies preparedness, response. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 2002 to 31 July 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/. [Accessed 4 February 2018].

- 5.World Health Organization . 2010. Emergencies preparedness, response. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 — update 112. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_08_06/en/index.html. [Accessed 15 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X., Chughtai A.A., Dyda A., MacIntyre C.R. Comparative epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia and South Korea. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6:e51. doi: 10.1038/emi.2017.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacIntyre C.R., Chughtai A.A., Seale H., Richards G.A., Davidson P.M. Respiratory protection for healthcare workers treating Ebola virus disease (EVD): are face masks sufficient to meet occupational health and safety obligations? Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:1421–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkhy H.H., El-Saed A., Sallah M. Epidemiology of H1N1 (2009) influenza among healthcare workers in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia: a 6-month surveillance study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:1004–1010. doi: 10.1086/656241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeom J.S., Lee J.H., Bae I.G., Oh W.S., Moon C.S., Park K.H. 2009 H1N1 influenza infection in Korean healthcare personnel. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1201–1206. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1213-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacIntyre C.R., Chughtai A.A., Seale H., Richards G.A., Davidson P.M. Uncertainty, risk analysis and change for Ebola personal protective equipment guidelines. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:899–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Disease and Control Prevention (CDC) 2010. Interim guidance on infection control measuresfor 2009 H1N1 influenza in healthcare settings, including protection of healthcare personnel. https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/guidelines_infection_control.htm. [Accessed 15 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . 2014. Infection prevention and control guidance for care of patients in health-care settings, with focus on Ebola. Interim guidance. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/filovirus_infection_control/en/. [Accessed 15 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel J.D., Rhinehart E., Jackson M., Chiarello L., Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(Suppl 2):S65–S164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Infection prevention and control of epidemic- and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care. WHO guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon J.H., Burnham C.D., Reske K.A., Liang S.Y., Hink T., Wallace M.A. Assessment of healthcare worker protocol deviations and self-contamination during personal protective equipment donning and doffing. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:1077–1083. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2015. Guidance on personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used by healthcare workers during management of patients with confirmed Ebola or persons under investigation (PUIs) for Ebola who are clinically unstable or have bleeding, vomiting, or diarrhea in U.S. hospitals, including procedures for donning and doffing PPE. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/ppe/guidance.html. [Accessed 15 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derrick J.L., Gomersall C.D. Protecting healthcare staff from severe acute respiratory syndrome: filtration capacity of multiple surgical masks. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59(April (4)):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacIntyre C.R., Chughtai A.A. Face masks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h694. h694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Pakistan, http://www.healthdata.org/pakistan. [Accessed 22 March 2018].

- 20.Waheed Y., Khan M.A., Fatima R., Yaqoob A., Mirza A., Qadeer E. Infection control in hospitals managing drug-resistant tuberculosis in Pakistan: how are we doing? Public Health Action. 2017;7:26–31. doi: 10.5588/pha.16.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chughtai A.A., MacIntyre R., Peng Y., Wang Q., Ashraf M.O., Dung T.C. Infection control survey in the hospitals to examine the role of masks and respirators for the prevention of respiratory infections in HCWs. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21(Suppl 1):408. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chughtai A.A., MacIntyre C.R., Ashraf M.O., Zheng Y., Yang P., Wang Q. Practices around the use of masks and respirators among hospital health care workers in 3 diverse populations. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(Suppl 2):1116–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baqi S., Damani N.N., Shah S.A., Khanani R. Infection control at a government hospital in Pakistan. Int J Infect Control. 2009;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain Z.A., Hussain S.A., Hussain F.A. Medical students’ knowledge, perceptions, and behavioral intentions towards the H1N1 influenza, swine flu, in Pakistan: a brief report. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:e11–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javed S., Zaboli M., Zehra A., Shah N. Assessment of the protective measures taken in preventing nosocomial transmission of pulmonary tuberculosis among health-care workers. East J Med. 2012;17:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasim S., Shahid A., Mustufa M.A., Arain G.M., Ali G., Taseer I.U. Biosafety perspective of clinical laboratory workers: a profile of Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:611–619. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasim S., Shahid A., Mustufa M.A., Kazmi S.U., Siddiqui T.R., Mohiuddin S. Practices and awareness regarding biosafety measures among laboratory technicians working in clinical laboratories in Karachi, Pakistan. Appl Biosaf. 2010;15:172–179. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan A.A., Javed O., Khan M., Mehboob B., Baig S. Cross infection control. Pak Oral Dent J. 2012;32:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed H. Infection control practices across Karachi: do dentists follow the recommendations? Med Forum Mon. 2014;25:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bokhari S.A.H., Sufia S., Khan A.A. Infection control practices among dental practitioners of Lahore, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohiuddin S., Dawani N. Knowledge attitude and practice of infection control measures among dental practitioners in public setup of Karachi, Pakistan: cross-sectional survey. J Dow Univ Health Sci. 2015;9:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahim N., Iffat W., Shakeel S., Naeem M.I., Qazi F., Rizvi M. Perspectives about pandemic influenza and its prophylactic measures among final year pharmacy students in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2017;9:144–151. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_328_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chughtai A.A., MacIntyre C.R., Zheng Y., Wang Q., Toor Z.I., Dung T.C. Examining the policies and guidelines around the use of masks and respirators by healthcare workers in China, Pakistan and Vietnam. J Infect Prev. 2015;16:68–74. doi: 10.1177/1757177414560251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chughtai A.A., Seale H., MacIntyre C.R. Availability, consistency and evidence-base of policies and guidelines on the use of mask and respirator to protect hospital health care workers: a global analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:216. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaws M.-L., Chughtai A.A., Salmon S., MacIntyre C.R. A highly precautionary doffing sequence for health care workers after caring for wet Ebola patients to further reduce occupational acquisition of Ebola. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:740–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones R.M., Brosseau L.M. Aerosol transmission of infectious disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:501–508. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tellier R. Aerosol transmission of influenza A virus: a review of new studies. J Royal Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl 6):S783–S790. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0302.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinney K.R., Gong Y.Y., Lewis T.G. Environmental transmission of SARS at Amoy Gardens. J Environ Health. 2006;68:26–30. quiz 51–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chughtai A.A., Barnes M., Macintyre C.R. Persistence of Ebola virus in various body fluids during convalescence: evidence and implications for disease transmission and control. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:1652–1660. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brosseau L.M., Jones R. 2014. Health workers need optimal respiratory protection for Ebola. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2014/09/commentary-health-workers-need-optimal-respiratory-protection-ebola. [Accessed 22 March 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterholm M.T., Moore K.A., Kelley N.S., Brosseau L.M., Wong G., Murphy F.A. Transmission of Ebola viruses: what we know and what we do not know. mBio. 2015;6 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00137-15. e00137–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IOM (Institute of Medicine) The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Preventing transmission of pandemic influenza and other viral respiratory diseases: personal protective equipment for healthcare personnel. Update 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim recommendations for facemask and respirator use to reduce 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus transmission, http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/masks.htm. 24 September 2009 [Accessed 25 March 2018].

- 44.Sim S.W., Moey K.S.P., Tan N.C. The use of face masks to prevent respiratory infection: a literature review in the context of the Health Belief Model. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:160–167. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2014037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chughtai A.A., Seale H., Dung T.C., Hayen A., Rahman B., Raina MacIntyre C. Compliance with the use of medical and cloth masks among healthcare workers in Vietnam. Ann Occup Hyg. 2016;60:619–630. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mew008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rebmann T., Wagner W. Infection preventionists’ experience during the first months of the 2009 novel H1N1 influenza A pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:e5–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lautenbach E., Saint S., Henderson D.K., Harris A.D. Initial response of health care institutions to emergence of H1N1 influenza: experiences, obstacles, and perceived future needs. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:523–527. doi: 10.1086/650169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomizuka T., Kanatani Y., Kawahara K. Insufficient preparedness of primary care practices for pandemic influenza and the effect of a preparedness plan in Japan: a prefecture-wide cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacIntyre C.R., Wang Q., Cauchemez S., Seale H., Dwyer D.E., Yang P. A cluster randomized clinical trial comparing fit-tested and non-fit-tested N95 respirators to medical masks to prevent respiratory virus infection in health care workers. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5:170–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rebmann T., Carrico R., Wang J. Physiologic and other effects and compliance with long-term respirator use among medical intensive care unit nurses. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:1218–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shenal B.V., Radonovich L.J., Jr., Cheng J., Hodgson M., Bender B.S. Discomfort and exertion associated with prolonged wear of respiratory protection in a health care setting. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2012;9:59–64. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.635133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seale H., Leem J.-S., Gallard J., Kaur R., Chughtai A.A., Tashani M. The cookie monster muffler: perceptions and behaviours of hospital healthcare workers around the use of masks and respirators in the hospital setting. Int J Infect Control. 2014:11. [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeJoy D.M., Searcy C.A., Murphy L.R., Gershon R.R. Behavioral-diagnostic analysis of compliance with universal precautions among nurses. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:127–141. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenstock I.M., Strecher V.J., Becker M.H. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang C.S., Wong C.Y. Factors influencing the wearing of face masks to prevent the severe acute respiratory syndrome among adult Chinese in Hong Kong. Prev Med. 2004;39:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong C.-Y., Tang C.S.-K. Practice of habitual and volitional health behaviors to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Casalino E., Astocondor E., Sanchez J.C., Díaz-Santana D.E., Del Aguila C., Carrillo J.P. Personal protective equipment for the Ebola virus disease: a comparison of 2 training programs. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chughtai A.A., Chen X., Macintyre C.R. Risk of self-contamination during doffing of personal protective equipment. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(12):1329–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]